Highlights

► Experimental methods to study virus–host interactomes including mammalian validation systems. ► Yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) as classical high-throughput method for protein–protein interaction analysis. ► Cellular antiviral drug target candidates. ► HTY2H screening identifies immunophilins (cyclophilins and FK506-binding proteins) as anticoronaviral targets. ► cyclosporine A has broad-spectrum anticoronaviral potential.

Abstract

One of the key questions in virology is how viruses, encoding relatively few genes, gain temporary or constant control over their hosts. To understand pathogenicity of a virus it is important to gain knowledge on the function of the individual viral proteins in the host cell, on their interactions with viral and cellular proteins and on the consequences of these interactions on cellular signaling pathways. A combination of transcriptomics, proteomics, high-throughput technologies and the bioinformatical analysis of the respective data help to elucidate specific cellular antiviral drug target candidates. In addition, viral and human interactome analyses indicate that different viruses target common, central human proteins for entering cellular signaling pathways and machineries which might constitute powerful broad-spectrum antiviral targets.

Current Opinion in Virology 2012, 2:614–621

This review comes from a themed issue on Antivirals and resistance

Edited by Daniel Lamarre and Mark A Wainberg

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

1879-6257/$ – see front matter, © 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Since decades, researchers have struggled to discover highly effective drugs with broad-range antiviral activity. Nowadays, almost all antiviral drugs used for clinical treatment only target particular viruses and subunits thereof. Inhibitors directed at specific viral proteins (e.g., proteases, replicases, and reverse transcriptases) are frequently used as antivirals. Often, these antivirals have little broad-range activity. However, the replication cycle of viruses is dependent on viral proteins as well as host cellular cofactors which by far outnumber viral proteins. Therefore, it is important to study virus–host interactions and to identify key cellular cofactors or signaling pathways that are commonly needed by different viruses. Drugs designed to target those cofactors and signaling pathways may be considered broad-range antiviral candidates. Furthermore, resistance against cellular targets is not expected to develop rapidly. In recent years, combinations of experimental high-throughput (HT) technologies and bioinformatics allowed the system-wide study of virus–host relations at the level of transcriptomes, metabolomes, and proteomes. This review will focus on protein–protein interactions (PPIs) as one strategy to study virus–host relations. It will first give a brief summary on methods used to study virus–host interactions, describe some prominent examples of genome-wide interaction studies including structural aspects, and then focus on a specific host–protein family (immunophilins) necessary for the replication of several viruses including coronaviruses. These proteins appear to be suitable for the development of broad-range antivirals.

Experimental methods to study virus–host interactomes

Proteomic changes can be studied at the level of individual virus–host protein interactions, organelles, and whole cells. 2D-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry (MS) have been used in numerous studies to identify gene expression patterns in infected cells [1••]. While 2D-PAGE methods and variations thereof allow the identification, relative quantification, and comparison of the abundant protein in infected versus noninfected samples, very small, very large, hydrophobic and low-abundance proteins are difficult to resolve. Drawbacks are a frequent limitation in reproducibility and lack of HT capabilities. Mass spectrometry is an excellent means of protein identification. Isobaric tagging techniques [2] including stable isotope labeling by amino acids (SILAC) in cell culture allow quantitative examination of virus–host cell relations and have improved the field significantly [3•]. MS-based techniques have recently also been used to characterize host–pathogen interactions within purified, mature virus particles including vaccinia virus [4], influenza virus [5], HIV [6], vesicular stomatitis virus [7], SARS-Corona virus [8•], and several herpes viruses [9•]. Finally, the two-hybrid-based mammalian PPI trap (MAPPIT), which drives a cellular signaling cascade with an endogenous transcriptional reporter, has been used as a HT assay for HCV and HIV-1 proteins and for human protein interactome analysis [10, 11].

Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) is a popular and intensely used alternative for studying virus–host protein–protein interaction on a global proteome scale [12•]. It exploits yeast genetic engineering and the modularity of eukaryotic transcription factors (TFs) utilizing DNA-binding domains (DBD) and activating domains (AD). Bait proteins fused to DBD and prey proteins fused to AD reconstitute functional TFs (e.g., yeast GAL4) upon interaction of the fusion proteins to be tested. The system can be used in a HT manner performing array-based matrix screens (e.g., all virus proteins against each other) or screens of individual bait virus proteins against cDNA prey libraries of different origin [13•]. Former allows the establishment of intraviral [14•], latter of virus–host interactomes [15••, 16]. Concepts of virus–host interactome studies are outlined in Figure 1 . There are limitations to the Y2H system as the transcriptional reporter system is on the basis of nuclear localization, which limits the analysis of hydrophobic membrane proteins because of possible disruption of the nuclear membrane. Also, the lack of mammalian translational modifications might contribute to the detection rate of about a quarter of all interactions as estimated in recent studies [17••, 18]. False positive interactions, a further drawback, can be efficiently prevented using proper controls, thus resulting in high-quality large-scale screens [19]. Increasing reliability by decreasing false-negative rates has recently been achieved by systematically combining screening strategies using novel N-terminal bait and C-terminal bait and prey fusion-protein vectors [20•]. Biological significance can be addressed by the validation of Y2H interactions with different biochemical and/or mammalian cell-based methods. Co-immunoprecipitation was successfully applied to co-produced proteins containing short fusion tags in mammalian cells [14•, 21]. As this method is very time-consuming, it is only applicable to small-scale evaluations. The LUMIER (LUminescence-based Mammalian IntERactome mapping) [22••] assay or modified versions thereof [15••] are pull-down assays with bait proteins used as fusions to Flag-tag or Protein A and with prey proteins used as fusions to luciferase (and vice versa) for detection. This methods as well as protein fragment complementation assays (PCAs) such as split-YFP-based or split-luciferase-based methods are well suited for HT screening. In the latter two assays, the test proteins are fused to subdomains of YFP [23•] or luciferase [24]. Upon physical interaction of the bait and prey proteins, the respective YFP or luciferase fragments reconstitute the fluorescent or enzymatic activities, respectively. A split beta-lactamase interaction assay has very recently been described as a cell-free test for the screening of small molecular peptide inhibitors [25]. A very intriguing fluorescent two-hybrid (F2H) assay allows the direct visualization and analysis of PPIs in single living cells utilizing a stable nuclear interaction platform [26•].

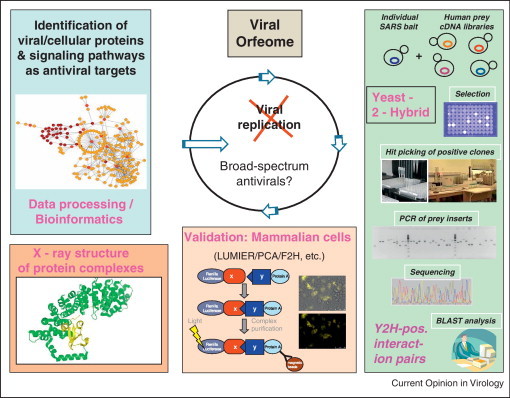

Figure 1.

Concept of studying virus–host interactions by large-scale high throughput methods. Y2H is used for initial screening of viral orfeomes (cloned virus ORFs) against human cDNA libraries expressing human genes. Positive protein interaction pairs are validated in mammalian cells by various methods including (modified) LUMIER, PCA, F2H, etc. Crystal structure analysis is performed on especially interesting protein interaction complexes. Bioinformatic analysis of cellular interaction partners of viral proteins aims at the identification of viral and cellular proteins and signaling pathways as targets for antiviral therapy.

Identification of cellular antiviral drug target candidates by HT screening

In recent years, there have been several publications on genome-wide genetic screens for host-cellular cofactors of influenza virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), severe acute respiratory virus (SARS-CoV), and other viruses [12•, 15••, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36••].

In the field of influenza virus, dsRNA, and siRNA, yeast-2-hybrid screening was applied to select host genes crucial for influenza virus infection [27, 31, 32, 33, 35]. Shaw et al. compared the results of these screens and sorted the major selected cellular cofactors into six functional categories [36••]. The gene classification clusters are ribosome, COPI vesicle, proton-transporting V-type ATPase complex, spliceosome, nuclear pore/envelope, and kinase/signaling. The involvement of ribosomes is not surprising, as they are responsible for catalyzing synthesis of proteins from amino acids, not only of host cells but also of viruses. In addition to influenza virus, the ribosome has been demonstrated to play roles during infection by other viruses. For example, SARS-CoV nonstructural protein (Nsp-1) binds to the 40S ribosomal subunit to inactivate the translational activity of these subunits and induces host-mRNA degradation in SARS-CoV-infected cells [37, 38]. The vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (vATPase) complex acidifies endosomes. This step is required for the fusion of the viral and endosomal membranes and results in subsequent release of the viral genome into the cytosol. Thereby, the activity of the vATPase complex is theoretically important for the entry of all viruses taking advantage of the host cell's endocytic machinery, such as SARS-CoV [39], and semliki forest virus [40], but perhaps not for the viruses which enter cells via direct membrane fusion. The importance of nuclear pore/envelope-associated proteins has been indicated previously [12•]. For instance, human KPNA1 (karyopherin alpha 1 or importin alpha 5) is an interacting partner of SARS-CoV accessory protein 6 and HCV nonstructural protein NS3 [34, 41]. Human KPNA2 (karyopherin alpha 2 or importin alpha 1) interacts with multiple viral pathogen groups including SARS-CoV, adenovirus, and HIV [41, 42•]. Human KPNB1 (karyopherin beta 1), which forms a heterodimer with karyopherin alpha to assist the import of proteins with a nuclear localization signal (NLS), was found in all of the five influenza screens [36••]. Kinase signaling is a very broad category. In this category, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling seems to play an important role during not only influenza virus infection but also HCV infection [34, 36••]. In addition, the phosphorylation-mediated JAK/STAT signaling regulating expression of interferon-stimulated genes is also involved in response to multiple viral pathogens [42•]. The abundant kinase signaling category provides many druggable targets such as MAP2K3 and CDC-like kinase 1, inhibition of which reduced influenza virus replication by more than two orders of magnitude [32].

Bioinformatical identification of cellular targets as broad-range antiviral targets

Naturally, drugs targeting viral proteins tend to be virus-specific. Drugs directed against cellular proteins or signaling pathways potentially have a much broader spectrum of antiviral activity, as different viruses may require similar cellular functions for replication. As described before, several druggable cellular proteins might serve as antiviral targets. For various viruses, especially for influenza virus, systematic surveys of small-compound libraries for antiviral activities were performed utilizing highly sophisticated HTS methodologies. However, as in the case of influenza virus, no efficient antivirals have been approved this way until now [43].

Instead of determining gene expression by measuring mRNA levels in virus-infected cells, it might be more efficient to look for direct PPIs utilizing, for example ‘classical’ Y2H screening in combination with HT. Several intraviral protein networks (Epstein–Barr Virus [EBV], Influenza A Virus [FLUAV], HCV, Herpes-Simplex-Virus 1, Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus, SARS-CoV, and Varicella Zoster Virus) and virus–host protein networks (Dengue Virus, EBV, FLUAV, HCV, Vaccinia Virus) were bioinformatically analyzed indicating that viral proteins target highly central human proteins which define Achilles’ heels of the human interactome [44••]. Accordingly, viruses seem to share host proteins as targets for overtaking cellular signaling pathways and machineries which might constitute attractive broad-spectrum antiviral targets.

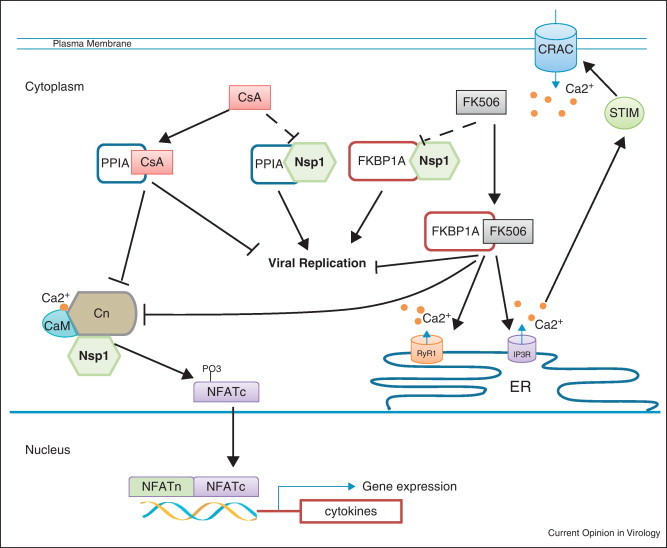

A SARS-CoV HTY2H screen identifies immunophilins as broad-spectrum anticoronaviral targets

A HTY2H approach was very recently used successfully in the coronavirus field: in unbiased, hypothesis-free screens, the SARS-CoVorfeome including subfragments thereof were tested against human cDNA libraries leading to the identification of human immunophilin (cyclophilins and FK506-binding proteins [FKBPs]) gene families as prerequisites for virus replication. The respective proteins have been known for many years to be inhibited by the immunosuppressive compounds cyclosporine A (CsA) and FK506. The interaction of the SARS-CoV Nsp1 protein with the cyclophilins PPIA, PPIG, and PPIH, with the FKBPs FKBP1A (FKBP12) and FKBP1B (FKBP12.6) as well as with the calcipressins RCAN1 and RCAN3 (also confirmed by a modified luminescence-based mammalian interactome-mapping assay) [22••] was eye-catching, particularly with regard to their influences on the cellular serine phosphatase calcineurin (Cn) [15••]. On the basis of the well-known complex formations between cyclophilins/CsA and FKBP/FK506, two important issues arose on the pathogenesis and on the replication of SARS-CoV. Figure 2 shows the influences of cyclophilin/CsA and FKBP/FK506 and the possible involvement of SARS-CoV Nsp1 on NFAT regulation and virus replication. Regarding pathogenicity, the induction of the immunologically very important Cn/NFAT (Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells) pathway by the virus and the viral Nsp1 might provide a possible explanation for the highly disordered cytokine levels (‘cytokine storms’) in SARS patients [45]. However, it is not known how the Nsp1 protein influences NFAT induction. It was further shown that CsA inhibits replication of not only SARS-CoV, but also of two other human coronaviruses, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E, and of the animal CoVs Feline CoV (FCoV), Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus (TGEV, pig), and Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV, bird). As CsA inhibits representatives of all three CoV genera (alpha-CoV, beta-CoV, gamma-CoV) it might thus serve as a pan-coronavirus inhibitor. As gammacoronaviruses lack Nsp1, it is highly possible that other coronaviral proteins are also involved in the interaction with cyclophilin. Such an interaction has been demonstrated in vitro for the SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein [46].

Figure 2.

Influence of CsA, FK506, and SARS-CoV Nsp1 on NFAT signaling (i) and viral replication (ii). (i) CsA and FK506 interact with PPIA and FKBP1A, respectively. The complex of CsA/PPIA or FK506/FKBP1A blocks the catalytic domain of calcineurin (Cn), thereby inhibiting dephosphorylation of NFATc transcription factors. Consequently, the phosphorylated NFATc cannot translocate into the nucleus to induce expression of cytokines [66, 67]. FKBP1A also interacts with the ryanodine receptor (RyR1) and the inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R), which are calcium channels at the ER membrane [68, 69]. Adding FK506 results in calcium release from the ER. Decrease of the calcium concentration at the ER is then sensed by the stromal interaction molecule (STIM). Subsequently, STIM activates the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel (CRAC) via protein–protein interaction at the plasma membrane, resulting in Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space [70]. The Ca2+ influx is required for the activation of Cn through a calcium sensor calmodulin CaM. SARS-CoV Nsp1 binds to Cn (own observation, unpublished). Virus infection and Nsp1 overexpression induce NFAT activity in vitro, which is blocked in the presence of CsA and FK506. (ii) Nsp1 binds to PPIA and FKBP1A. CsA binding to PPIA or FK506 binding to FKBP1A inhibit coronaviral replication in cell culture, probably by interrupting the formation of PPIA/Nsp1 or FKBP1A/Nsp1 complexes.

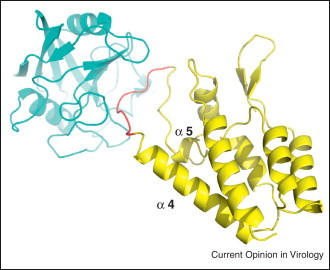

The mechanism of inhibition of coronavirus replication by CsA is not clear. It is reasonable to assume, however, that in analogy to HIV-1 [47] and HCV [48], the peptidyl-cis-trans isomerase and chaperon activities of the cyclophilins are blocked by CsA, leading to improper folding of viral proteins. In case of HIV-1, a crystal structure of the complex between cyclophilin and the viral capsid protein (CA) is available [49]. The flexible loop between helix alpha 4 and the helical turn alpha 5 of CA binds the active groove of cyclophilin (Figure 3 ). Interestingly, the conformation of cyclophilin A in complex with CA is very similar to that of the free enzyme or its complexes with CsA and other ligands. Thus, cyclophilin A appears to be a rigid scaffold protein, a fact that facilitated the structure-based design of compounds which can compete with CA for binding. A series of thiourea compounds have been designed as inhibitors targeting this interaction; some of these have been shown to block HIV-1 replication [50]. Also, an interaction between HIV-1 vpr and cyclophilin A was demonstrated [51].

Figure 3.

Cartoon view of cyclophilin A (cyan) and HIV-1 capsid (yellow) complex structure (PDB ID: 1AK4) [49]. The binding site of CsA overlaps with the loop (red) connecting alpha helix 4 and the helical turn alpha 5 of CA, which binds to the active groove of cyclophilin.

CsA also exerts inhibitory effects on HSV-1 [52], vaccinia virus [53], BK polyoma virus [54] and influenza virus by cyclophilin A-dependent and cyclophilin A-independent pathways [55]. FK506 also inhibits the human CoVs SARS-CoV, NL63, and 229E [56•]. It was found to have an inhibitory effect on chronically but not on newly HIV-1-infected cells (up to 10 μg/ml FK506 [57]). Replication of replicon HCV RNA up to concentrations of 3 μg/ml was also not affected [48]. Orthopoxviruses however were inhibited by FK506 [58]. Anti-immunophilin drugs are very promising antiviral candidates. However, severe immunosuppressive side effects are normally undesirable. These can be overcome by the development of nonimmmunosuppressive derivates of the drugs which still display antiviral activity by destroying the calcineurin-binding site and the preservation of the cyclophilin-binding activity. A very promising example is the CsA derivative Debio-025, SCY-635, NIM-811 which has been demonstrated to inhibit HCV and HIV-1 replication very efficiently [59••].

Conclusions

Integrated viral ORFeome databases designed to generate versatile collections of viral ORFs [60], viral [61], and virus–host protein [62] interaction databases are extremely valuable tools for the comparison and analysis of an increasing several virus interactomes as well as individual proteins at the intraviral and at the virus–host level. Several assays are available to study virus–host relations, each carrying intrinsic advantages and disadvantages. Techniques addressing interactions at the protein, not only at the RNA level, might be more promising with respect to inhibitor identification because of, for example the role played by post-transcriptional modifications. Indeed, by HTY2H screening of the SARS-CoVorfeome against human cDNA libraries, we have identified members of the cyclophilin and FKBP protein families as prerequisites for coronavirus replication. Interaction of the SARS-CoV Nsp1 protein with these cellular proteins led to the discovery of the natural cyclophilin A ligand CsA as an inhibitor of animal and human coronaviruses (pan-coronavirus inhibitor) and of the natural FKBP-ligand FK506 as an inhibitor of human coronaviruses. A second but independent aspect of this interaction was the discovery of the upregulation of the immunologically very important Cn/NFAT signaling pathway by SARS-CoV Nsp1 and the virus itself, which might provide an explanation of the so-called cytokine storms in SARS patients. From a technical point of view, it may be noted that the described Nsp1 interactions occurred with low abundance in the Y2H screens. The relevance of these cellular protein families to coronavirus biology was first realized by very careful ‘eye inspection’ of and contemplation on the interaction data keeping related literature in mind. That is, the construction of large and colorful interaction maps per se does not necessarily give hints on relevant cellular target molecules or signaling pathways for antiviral therapy. Undoubtedly, interaction databases and databases specializing in drug target PPIs, PPI-inhibiting small molecules, and integrative systems for assessing the druggability of PPIs [63, 64, 65] will provide invaluable computerized tools for the development of antivirals in the future.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant of the ‘Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung’ of the German Federal Government (Zoonosis Network, Consortium on ecology and pathogenesisis of SARS, project code 01KI1005A,F; http://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/1721.php# SARS) to AvB. RH is supported by the DFG through its Cluster of Excellence ‘Inflammation at Interfaces’ (EXC 306), by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, by the Chinese Academy of Sciences through a Visiting Professorship for Senior International Scientists (grant no. 2010T1S6), and the Schleswig-Holstein Innovation Fund. He also thanks the European Commission for support through its SILVER project (contract no. HEALTH-F3-2010-260644).

References

- 1••.Maxwell K.L., Frappier L. Viral proteomics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:398–411. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00042-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gives an overview on ‘proteomic studies conducted on all eukaryotic viruses and bacteriophages, covering virion composition, viral protein structures, virus–virus and virus–host protein interactions, and changes in the cellular proteome upon viral infection’.

- 2.Treumann A., Thiede B. Isobaric protein and peptide quantification: perspectives and issues. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2010;7:647–653. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Munday D.C., Surtees R., Emmott E., Dove B.K., Digard P., Barr J.N., Whitehouse A., Matthews D., Hiscox J.A. Using SILAC and quantitative proteomics to investigate the interactions between viral and host proteomes. Proteomics. 2012;12:666–672. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gives an overview on virus–host interactomics using SILAC and quantitative proteomics techniques.

- 4.Krauss O., Hollinshead R., Hollinshead M., Smith G.L. An investigation of incorporation of cellular antigens into vaccinia virus particles. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2347–2359. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-10-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw M.L., Stone K.L., Colangelo C.M., Gulcicek E.E., Palese P. Cellular proteins in influenza virus particles. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000085. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott D.E. Cellular proteins detected in HIV-1. Rev Med Virol. 2008;18:159–175. doi: 10.1002/rmv.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moerdyk-Schauwecker M., Hwang S.I., Grdzelishvili V.Z. Analysis of virion associated host proteins in vesicular stomatitis virus using a proteomics approach. Virol J. 2009;6:166. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Neuman B.W., Joseph J.S., Saikatendu K.S., Serrano P., Chatterjee A., Johnson M.A., Liao L., Klaus J.P., Yates J.R., 3rd, Wuthrich K. Proteomics analysis unravels the functional repertoire of coronavirus nonstructural protein 3. J Virol. 2008;82:5279–5294. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02631-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Very informative proteomics study on purified SARS-CoV particles.

- 9•.Lippe R. Deciphering novel host–herpesvirus interactions by virion proteomics. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:181. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Very informative overview of recent herpesviral interactomic studies.

- 10.Van Schoubroeck B., Van Acker K., Dams G., Jochmans D., Clayton R., Berke J.M., Lievens S., Van der Heyden J., Tavernier J. MAPPIT as a high-throughput screening assay for modulators of protein–protein interactions in HIV and HCV. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;812:295–307. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-455-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lievens S., Vanderroost N., Defever D., Van der Heyden J., Tavernier J. ArrayMAPPIT: a screening platform for human protein interactome analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;812:283–294. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-455-1_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Mendez-Rios J., Uetz P. Global approaches to study protein–protein interactions among viruses and hosts. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:289–301. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Very informative overview of systematic virus–host protein–protein interaction studies.

- 13•.Roberts G.G., 3rd, Parrish J.R., Mangiola B.A., Finley R.L., Jr. High-throughput yeast two-hybrid screening. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;812:39–61. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-455-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Useful information on HTY2H.

- 14•.von Brunn A., Teepe C., Simpson J.C., Pepperkok R., Friedel C.C., Zimmer R., Roberts R., Baric R., Haas J. Analysis of intraviral protein–protein interactions of the SARS coronavirus ORFeome. PLoS One. 2007;2:e459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes the first SARS-CoV intraviral interactome study.

- 15••.Pfefferle S., Schopf J., Kogl M., Friedel C.C., Muller M.A., Carbajo-Lozoya J., Stellberger T., von Dall’Armi E., Herzog P., Kallies S. The SARS-coronavirus–host interactome: identification of cyclophilins as target for pan-coronavirus inhibitors. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002331. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes the first SARS-CoV–host interactome study identifying cyclophilins as necessary for coronavrius replication, cyclosporine A as a pan-coronavirus inhibitor and the possible involvement of the calcineurin/NFAT pathway in the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV.

- 16.Mohr K., Koegl M. High-throughput yeast two-hybrid screening of complex cDNA libraries. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;812:89–102. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-455-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17••.Braun P., Tasan M., Dreze M., Barrios-Rodiles M., Lemmens I., Yu H., Sahalie J.M., Murray R.R., Roncari L., de Smet A.S. An experimentally derived confidence score for binary protein–protein interactions. Nat Methods. 2009;6:91–97. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Study defining confidence scores for high-throughput methods (LUMIER, MAPPIT, PCA [split YFP], NAPPA) used to validate Y2H protein–protein interactions.

- 18.Rajagopala S.V., Titz B., Goll J., Parrish J.R., Wohlbold K., McKevitt M.T., Palzkill T., Mori H., Finley R.L., Jr., Uetz P. The protein network of bacterial motility. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:128. doi: 10.1038/msb4100166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu H., Braun P., Yildirim M.A., Lemmens I., Venkatesan K., Sahalie J., Hirozane-Kishikawa T., Gebreab F., Li N., Simonis N. High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science. 2008;322:104–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1158684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Stellberger T., Hauser R., Uetz P., Brunn A. Yeast two-hybrid screens: improvement of array-based screening results by N- and C-terminally tagged fusion proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;815:277–288. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-424-7_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Useful information on improved HTY2H on the basis of N-terminally and C-terminally tagged DNA-binding and activating domains.

- 21.Fossum E., Friedel C.C., Rajagopala S.V., Titz B., Baiker A., Schmidt T., Kraus T., Stellberger T., Rutenberg C., Suthram S. Evolutionarily conserved herpesviral protein interaction networks. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000570. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22••.Barrios-Rodiles M., Brown K.R., Ozdamar B., Bose R., Liu Z., Donovan R.S., Shinjo F., Liu Y., Dembowy J., Taylor I.W. High-throughput mapping of a dynamic signaling network in mammalian cells. Science. 2005;307:1621–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1105776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hallmark study on mammalian validation assays for protein–protein interactions.

- 23•.Nyfeler B., Michnick S.W., Hauri H.P. Capturing protein interactions in the secretory pathway of living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6350–6355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501976102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes very interesting protein–protein interaction validation method: ‘Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-based protein fragment complementation assay (PCA) to detect protein–protein interactions in the secretory pathway of living cells’.

- 24.Cassonnet P., Rolloy C., Neveu G., Vidalain P.O., Chantier T., Pellet J., Jones L., Muller M., Demeret C., Gaud G. Benchmarking a luciferase complementation assay for detecting protein complexes. Nat Methods. 2011;8:990–992. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnee M., Wagner F.M., Koszinowski U.H., Ruzsics Z. A cell free protein fragment complementation assay for monitoring the core interaction of the human cytomegalovirus nuclear egress complex. Antiviral Res. 2012;95:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Zolghadr K., Rothbauer U., Leonhardt H. The fluorescent two-hybrid (F2H) assay for direct analysis of protein–protein interactions in living cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;812:275–282. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-455-1_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describe a simple fluorescent two-hybrid (F2H) assay to directly visualize and analyze protein–protein interactions in single living cells utilizing a stable nuclear interaction platform.

- 27.Brass A.L., Huang I.C., Benita Y., John S.P., Krishnan M.N., Feeley E.M., Ryan B.J., Weyer J.L., van der Weyden L., Fikrig E. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139:1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bushman F.D., Malani N., Fernandes J., D‘Orso I., Cagney G., Diamond T.L., Zhou H., Hazuda D.J., Espeseth A.S., Konig R. Host cell factors in HIV replication: meta-analysis of genome-wide studies. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000437. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Y.Q., Wang L., Cheng J., Liu Y., Xu D.P., Zhong Y.W., Qu J.H., Tian J.K., Dai J.Z., Li X.D. Screening and identification of proteins interacting with HCV NS4A via yeast double hybridization in leukocytes and gene cloning of the interacting protein. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2007;21:47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das S., Kalpana G.V. Reverse two-hybrid screening to analyze protein–protein interaction of HIV-1 viral and cellular proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;485:271–293. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-170-3_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao L., Sakurai A., Watanabe T., Sorensen E., Nidom C.A., Newton M.A., Ahlquist P., Kawaoka Y. Drosophila RNAi screen identifies host genes important for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2008;454:890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature07151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlas A., Machuy N., Shin Y., Pleissner K.P., Artarini A., Heuer D., Becker D., Khalil H., Ogilvie L.A., Hess S. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies human host factors crucial for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konig R., Stertz S., Zhou Y., Inoue A., Hoffmann H.H., Bhattacharyya S., Alamares J.G., Tscherne D.M., Ortigoza M.B., Liang Y. Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463:813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature08699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q., Brass A.L., Ng A., Hu Z., Xavier R.J., Liang T.J., Elledge S.J. A genome-wide genetic screen for host factors required for hepatitis C virus propagation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16410–16415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapira S.D., Gat-Viks I., Shum B.O., Dricot A., de Grace M.M., Wu L., Gupta P.B., Hao T., Silver S.J., Root D.E. A physical and regulatory map of host–influenza interactions reveals pathways in H1N1 infection. Cell. 2009;139:1255–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36••.Shaw M.L. The host interactome of influenza virus presents new potential targets for antiviral drugs. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21:358–369. doi: 10.1002/rmv.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Very informative review on influenza–host interactomic studies.

- 37.Huang C., Lokugamage K.G., Rozovics J.M., Narayanan K., Semler B.L., Makino S. SARS coronavirus nsp1 protein induces template-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage of mRNAs: viral mRNAs are resistant to nsp1-induced RNA cleavage. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002433. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamitani W., Huang C., Narayanan K., Lokugamage K.G., Makino S. A two-pronged strategy to suppress host protein synthesis by SARS coronavirus Nsp1 protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H., Yang P., Liu K., Guo F., Zhang Y., Zhang G., Jiang C. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res. 2008;18:290–301. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez L., Carrasco L. Involvement of the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in animal virus entry. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(Pt 10):2595–2606. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frieman M., Yount B., Heise M., Kopecky-Bromberg S.A., Palese P., Baric R.S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF6 antagonizes STAT1 function by sequestering nuclear import factors on the rough endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi membrane. J Virol. 2007;81:9812–9824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42•.Dyer M.D., Murali T.M., Sobral B.W. The landscape of human proteins interacting with viruses and other pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e32. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes the modeling of virus interacomes into the human interactome.

- 43.Atkins C., Evans C.W., White E.L., Noah J.W. Screening methods for influenza antiviral drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2012;7:429–438. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.674510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Meyniel-Schicklin L., de Chassey B., Andre P., Lotteau V. Viruses and interactomes in translation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.014738. M111 014738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes up-to-date modeling of viral into host interactomes.

- 45.Huang K.J., Su I.J., Theron M., Wu Y.C., Lai S.K., Liu C.C., Lei H.Y. An interferon-gamma-related cytokine storm in SARS patients. J Med Virol. 2005;75:185–194. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luo C., Luo H., Zheng S., Gui C., Yue L., Yu C., Sun T., He P., Chen J., Shen J. Nucleocapsid protein of SARS coronavirus tightly binds to human cyclophilin A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Briggs C.J., Tozser J., Oroszlan S. Effect of cyclosporin A on the replication cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 derived from H9 and Molt-4 producer cells. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(Pt 12):2963–2967. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watashi K., Hijikata M., Hosaka M., Yamaji M., Shimotohno K. Cyclosporin A suppresses replication of hepatitis C virus genome in cultured hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2003;38:1282–1288. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gamble T.R., Vajdos F.F., Yoo S., Worthylake D.K., Houseweart M., Sundquist W.I., Hill C.P. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell. 1996;87:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J., Tan Z., Tang S., Hewlett I., Pang R., He M., He S., Tian B., Chen K., Yang M. Discovery of dual inhibitors targeting both HIV-1 capsid and human cyclophilin A to inhibit the assembly and uncoating of the viral capsid. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:3177–3188. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solbak S.M., Wray V., Horvli O., Raae A.J., Flydal M.I., Henklein P., Nimtz M., Schubert U., Fossen T. The host–pathogen interaction of human cyclophilin A and HIV-1 Vpr requires specific N-terminal and novel C-terminal domains. BMC Struct Biol. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vahlne A., Larsson P.A., Horal P., Ahlmen J., Svennerholm B., Gronowitz J.S., Olofsson S. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus production in vitro by cyclosporin A. Arch Virol. 1992;122:61–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01321118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Damaso C.R., Keller S.J. Cyclosporin A inhibits vaccinia virus replication in vitro. Arch Virol. 1994;134:303–319. doi: 10.1007/BF01310569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Acott P.D., O‘Regan P.A., Lee S.H., Crocker J.F. In vitro effect of cyclosporin A on primary and chronic BK polyoma virus infection in Vero E6 cells. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu X., Zhao Z., Li Z., Xu C., Sun L., Chen J., Liu W. Cyclosporin A inhibits the influenza virus replication through cyclophilin A-dependent and -independent pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56•.Carbajo-Lozoya J., Muller M.A., Kallies S., Thiel V., Drosten C., von Brunn A. Replication of human coronaviruses SARS-CoV, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E is inhibited by the drug FK506. Virus Res. 2012;165:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First description of the drug FK506 as inhibitor of human coronaviruses.

- 57.Briggs C.J., Ott D.E., Coren L.V., Oroszlan S., Tozser J. Comparison of the effect of FK506 and cyclosporin A on virus production in H9 cells chronically and newly infected by HIV-1. Arch Virol. 1999;144:2151–2160. doi: 10.1007/s007050050629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reis S.A., Moussatche N., Damaso C.R. FK506, a secondary metabolite produced by Streptomyces, presents a novel antiviral activity against Orthopoxvirus infection in cell culture. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;100:1373–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59••.Fischer G., Gallay P., Hopkins S. Cyclophilin inhibitors for the treatment of HCV infection. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:911–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Very informative review on nonimmunosuppressive inhibitors of HCV replication.

- 60.Pellet J., Tafforeau L., Lucas-Hourani M., Navratil V., Meyniel L., Achaz G., Guironnet-Paquet A., Aublin-Gex A., Caignard G., Cassonnet P. Viral ORFeome: an integrated database to generate a versatile collection of viral ORFs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D371–D378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chatr-aryamontri A., Ceol A., Peluso D., Nardozza A., Panni S., Sacco F., Tinti M., Smolyar A., Castagnoli L., Vidal M. VirusMINT: a viral protein interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D669–D673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Navratil V., de Chassey B., Meyniel L., Delmotte S., Gautier C., Andre P., Lotteau V., Rabourdin-Combe C. VirHostNet: a knowledge base for the management and the analysis of proteome-wide virus–host interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D661–D668. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sugaya N., Furuya T. Dr. PIAS: an integrative system for assessing the druggability of protein–protein interactions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bourgeas R., Basse M.J., Morelli X., Roche P. Atomic analysis of protein–protein interfaces with known inhibitors: the 2P2I database. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Higueruelo A.P., Schreyer A., Bickerton G.R., Pitt W.R., Groom C.R., Blundell T.L. Atomic interactions and profile of small molecules disrupting protein–protein interfaces: the TIMBAL database. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:457–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crabtree G.R., Schreiber S.L. SnapShot: Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Cell. 2009;138:210. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.026. 210e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sieber M., Baumgrass R. Novel inhibitors of the calcineurin/NFATc hub — alternatives to CsA and FK506? Cell Commun Signal. 2009;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brillantes A.B., Ondrias K., Scott A., Kobrinsky E., Ondriasova E., Moschella M.C., Jayaraman T., Landers M., Ehrlich B.E., Marks A.R. Stabilization of calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function by FK506-binding protein. Cell. 1994;77:513–523. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kang C.B., Hong Y., Dhe-Paganon S., Yoon H.S. FKBP family proteins: immunophilins with versatile biological functions. Neurosignals. 2008;16:318–325. doi: 10.1159/000123041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Penna A., Demuro A., Yeromin A.V., Zhang S.L., Safrina O., Parker I., Cahalan M.D. The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature. 2008;456:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]