Highlights

-

•

New therapies for infections caused by positive-strand RNA viruses are needed.

-

•

Novel nucleoside and nucleotide analogs that inhibit HCV have been developed.

-

•

Some of these molecules also inhibit other positive-strand RNA viruses.

-

•

Optimization of antiviral potency and/or target delivery is necessary.

Abstract

A number of important human infections are caused by positive-strand RNA viruses, yet almost none can be treated with small molecule antiviral therapeutics. One exception is the chronic infection caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV), against which new generations of potent inhibitors are being developed. One of the main molecular targets for anti-HCV drugs is the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, NS5B. This review summarizes the search for nucleoside and nucleotide analogs that inhibit HCV NS5B, which led to the FDA approval of sofosbuvir in 2013. Advances in anti-HCV therapeutics have also stimulated efforts to develop nucleoside analogs against other positive-strand RNA viruses. Although it remains to be validated in the clinic, the prospect of using nucleoside analogs to treat acute infections caused by RNA viruses represents an important paradigm shift and a new frontier for future antiviral therapies.

Current Opinion in Virology 2014, 9:1–7

This review comes from a themed issue on Virus replication in animals and plants

Edited by C Cheng Kao and Olve B Peersen

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

Available online 17th September 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2014.08.004

1879-6257/© 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Introduction: the RNA polymerase of HCV as the target for nucleoside analogs

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a member of the Flaviviridae family. Viruses from this family all contain a single-strand, positive-sense RNA genome of about 9.5 kb. The viral genome encodes only one open-reading frame translated into a polyprotein of approximately 3000 amino acids. HCV is estimated to have infected approximately 175 million individuals worldwide, with 2–4 million new infections occurring each year [1]. Until recently, treatment options for chronic HCV infections were largely suboptimal due to limited efficacy and substantial toxicity. The standard of care (SOC) was a 24-week or 48-week course of pegylated interferon alpha (PEG-IFN-α) in combination with ribavirin. Effective clearance or sustained virologic response (SVR) rate of the virus was achieved in less than 50% cases of genotype-1 infection, the most prevalent strain of HCV in the United States and Europe. Since 2011, two inhibitors of the viral serine protease, NS3/4A, boceprevir and telaprevir, were approved for use in combination with PEG-IFN-α and ribavirin. These molecules are called direct-acting antivirals (DAA) because they specifically bind to, and inhibit, a viral protein required for virus replication. Although the toxicity burden of these newer treatment options remains high, the SVR rate in the presence of protease inhibitors has improved to 70–80% in difficult-to-treat genotype-1 infections [2, 3]. Other DAAs that specifically block HCV enzymatic functions have been intensely studied over the last decade, and the polymerase function of NS5B has emerged as one of the most attractive targets for the next generation of anti-HCV therapy.

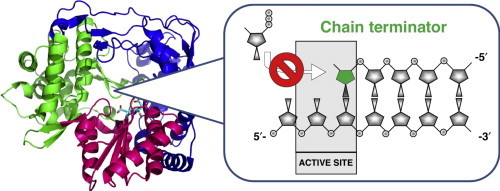

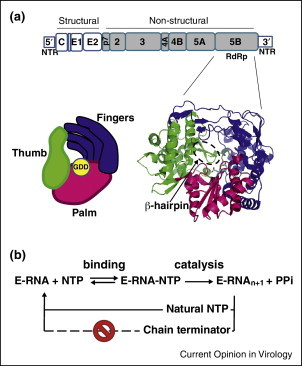

The HCV NS5B protein is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). NS5B is required both for replication of the viral genome by synthesis of the minus-strand intermediate and at the transcription level for synthesis of viral mRNA. The RdRp enzymatic activity of NS5B is unique to viruses and not found in human cells, which makes NS5B an attractive target for antiviral drug development (see [4] for a more detailed review on the structure and functions of NS5B). The NS5B protein is composed of 591 amino acids. Similar to other known RdRps, the HCV NS5B contains six conserved motifs designated A–F. The amino acids involved in the catalytic activity of NS5B are located within motif A (aspartate at position 220) and the catalytic triad GDD at position 318–320 in motif C [5••]. The orientation of these residues in the active site of NS5B and their contribution to the catalytic activity are supported by the crystal structure of the protein [5••, 6, 7••]. Using the polymerase right-hand analogy model, the HCV NS5B protein features the fingers, palm, and thumb subdomains (Figure 1 a). Unlike the traditional open-hand conformation shared by many DNA polymerases, the HCV NS5B features an encircled active site due to extensive interactions between the fingers and thumb subdomains. These contacts restrict the flexibility of the subdomains and favor the first steps — or initiation — of RNA synthesis leading to the formation of the primer strand. Therefore, important structural changes involving an opening of the thumb and the fingers are required for primer extension during the elongation steps [8, 9•, 10]. Another unique feature of NS5B is its β-hairpin loop that protrudes into the active site located at the base of the palm subdomain (Figure 1a). This 12 amino acid loop located within the thumb (residues 443–453) was suggested to interfere with binding to double-stranded RNA due to steric hindrance. Its deletion allows the enzyme to favor primer-dependent RNA synthesis [11, 12•, 13], and the resulting truncated protein was co-crystallized in the elongation mode with double-stranded RNA [14]. Primer extension also requires the C-terminal part of NS5B to move away from the catalytic site, a structural feature shared with other RNA polymerases [15]. Once these important conformational changes take place, the enzyme becomes processive and the efficiency of RNA synthesis increases considerably [16•, 17]. It is precisely during the elongation phase of RNA synthesis that HCV NS5B is inhibited by nucleotide analogs acting as chain terminators (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Structure and function of HCV RNA polymerase. (a) Organization of the structural and non-structural proteins encoded within the HCV genome. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase function is carried by NS5B, the last gene at the 3′-end of the open reading frame. The crystal structure of the NS5B protein shows a closed right-hand conformation, with the fingers (blue), palm (magenta), and thumb (green) subdomains (PDB = 1YVF, genotype 1b). The active site for nucleotide incorporation is located nearby the GDD catalytic motif (yellow) protein [5••, 6, 7••]. (b) During the elongation phase, RNA polymerases function by interactive steps of nucleoside 5′-triphoshpate (NTP) incorporation. The first step requires ground-state binding of the NTP, followed by catalysis of the new phosphodiester bond. The incorporation of a chain terminator at the 3′-end of the growing primer prevents the next step of NTP binding and/or catalysis. E-RNA, enzyme-RNA; NTR, non-translated region; PPi, pyrophosphate.

The evolution of HCV RNA polymerase inhibitors leading to the discovery of sofosbuvir

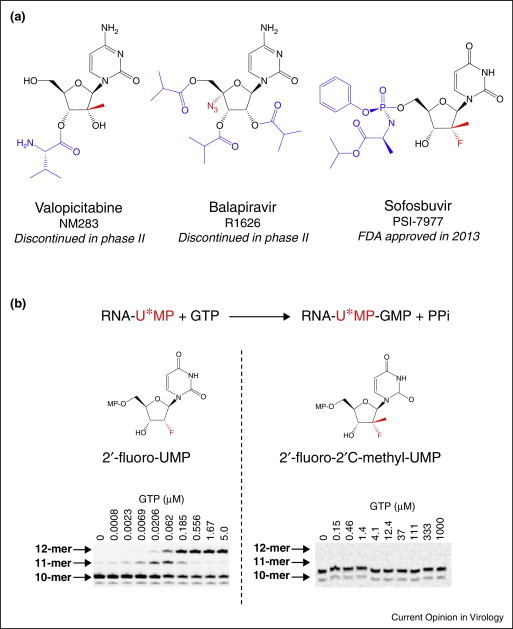

The initial major class of nucleoside analogs of therapeutic potential to demonstrate potent inhibition of HCV RNA polymerase activity were 2′C-methyl-ribonucleosides, The first 2′C-methyl ribonucleosides were originally synthesized in the 1960s [18]. Later, 2′C-methyl-uridine triphosphate was found to act as a chain terminator of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase [19, 20]. In antiviral assays, 2′C-methyl-cytidine was originally described as an inhibitor of bovine diarrhea virus (BVDV), a virus closely related to HCV and used as a surrogate [21, 22, 23, 24]. Although the compound was highly potent and selective in tissue culture, its low bioavailability made it unsuitable for oral dosing. This limitation was overcome by adding an l-valine ester group at the 3′-OH position on the sugar (Figure 2 a). The resulting drug, valopicitabine (NM283), was efficacious when dosed orally in HCV-infected chimpanzees [25]. Although this nucleoside significantly reduced HCV viral load in patients, its development was discontinued in phase II clinical trials due to dose-limiting gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity [26]. Other 2′C-methyl nucleosides such as 2′C-methyl-adenosine or 2′C-methyl-7-deaza-adenosine have been reported to inhibit HCV replication [27••, 28], but none were evaluated in clinical trials presumably due to tissue retention issues in preclinical species [29]. In vitro, prolonged culture of HCV replicon-containing hepatocytes with 2′C-methyl-nucleosides results in the selection of a single S282T mutation within NS5B, and the resulting polymerase is resistant to this class of nucleosides [30, 31, 32].

Figure 2.

Nucleoside and nucleotide analogs as inhibitors of HCV. (a) Representative molecules of the three main scaffolds of nucleoside analogs, with valopicitabine for the 2′C-methyl scaffold, balapiravir for the 4′azido scaffold, and sofosbuvir for the 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl scaffold. The nucleoside backbones are shown in black, the sugar modification in red, and the prodrug moieties are in blue. (b) Efficiency of chain termination of 2′-fluoro and 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl UMP. Principle of the reaction: elongation by HCV polymerase of RNA containing at the 3′-end a modified UMP (U*MP), in the presence of GTP as the next correct nucleotide. In the case of 2′-fluoro-UMP (left), the RNA is further extended with GTP from the 10-mer to the 11-mer and 12-mer positions. In contrast, the addition of the 2′C-methyl moiety to 2′-fluoro-UMP (right) completely blocks the ability of the enzyme to further extend the RNA with GTP [49]. GTP, guanosine triphosphate; UMP, uridine monophosphate.

The second class of anti-HCV nucleosides is the 4′-azido-nucleoside scaffold. Molecules in this class resemble 3′-azido-thymidine (AZT) and were originally synthesized for testing against human immunodeficiency virus [33•]. During compound library screening in the sub-genomic replicon assay, 4′azido-cytidine was later identified as a potent inhibitor of HCV [34]. In its 5′-triphosphate form, the inhibitor was recognized as a substrate for HCV NS5B, and its incorporation to the growing RNA strand resulted in immediate chain termination. One advantage of 4′-azido-cytidine over the 2′C-methyl-nucleosides was the lack of cross-resistance associated with the presence of the S282T mutation [34, 35]. The uridine analog counterpart was inactive in the replicon assay due to lack of intracellular phosphorylation. However, the 5′-triphosphate forms of both cytidine and uridine analogs were equally potent as chain terminators against HCV NS5B. The pharmacokinetic properties of 4′-azido-cytidine were further improved with the triester prodrug balapiravir (Figure 2a), which achieved a 3.7 log10 reduction in viral RNA at the highest dose in a 14-day phase 1b monotherapy clinical trial [36]. Four weeks of treatment with balapiravir in combination with SOC resulted in a further decrease in viral load, but also in hematologic adverse events such as lymphopenia, which led to the discontinuation of development of balapiravir for HCV infection [37]. Analogs of balapiravir with similar 4′-modification scaffolds have also been reported, but none have progressed into further development [38, 39, 40, 41]. Recently it was shown that 4′-azido-CTP is a good substrate for human mitochondrial RNA polymerase, one of the proteins considered to be responsible for the mitochondrial toxicity of several other ribonucleosides [42••].

The third major class of nucleoside analogs is the 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl modification, which includes sofosbuvir. The double substitution at the 2′-position on the ribose evolved from the earlier 2′C-methyl scaffold, combined with further change resulting from the observation that 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-cytidine was weakly active in the HCV replicon [43]. Compared with its 2′-fluoro mono-substituted counterpart, 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-cytidine (PSI-6130) was significantly more potent in the HCV replicon assay and less toxic to the Huh-7 hepatocarcinoma cells in vitro [44]. The parent 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-cytidine nucleoside was also developed as the orally bioavailable di-isobutyrate ester prodrug, mericitabine, which is currently under phase II clinical development. In an important series of experiments, it was found that 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-cytidine is metabolized also to its uridine 5′-triphosphate form as a result of intracellular deamination [45•, 46]. As the parent uridine analog was not readily converted to its monophosphate form by intracellular kinases, a series of monophosphate forms of 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-uridine were designed to bypass the first and most limiting kinase step [47]. Phosphoramidate prodrugs were made to mask the charges of the alpha-phosphate with an amino acid ester and an aryl group, both protecting groups being removed in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes after cell penetration [47]. Optimization of the leaving groups of the prodrug and separation of stereoisomers led to the selection of sofosbuvir (PSI-7977), as one of the most potent and selective inhibitors in this series (Figure 2a) [48]. In addition to forming high levels of the nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (NTP), the exquisite potency of sofosbuvir can be explained in vitro by the fact that its active form 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-uridine 5′-triphosphate is a very efficient substrate and chain terminator for HCV NS5B (Figure 2b) [49]. This study also showed that the 2′-fluoro substitution contributes less to chain termination than the 2′-C-methyl moiety. The NTP derivative of sofosbuvir is a very poor substrate for human mitochondrial RNA polymerase, one of the proteins considered to be responsible for the mitochondrial toxicity of several other ribonucleosides [42••]. Similar to the two former classes of inhibitors, many other 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-nucleosides have been evaluated, including the very potent monophosphate guanosine analog, PSI-353661, that progressed to phase II clinical trials, before being discontinued due to elevated alanine aminotransferase levels (see complete reviews of recent HCV nucleoside and nucleotide development in [4, 50, 51]).

The quest for structurally novel nucleoside inhibitors of HCV NS5B continues to be an active area of pharmaceutical research, and other chemical scaffolds have been recently discovered (e.g. [52, 53]). To this date, none of the other classes of nucleoside analogs have advanced beyond phase II clinical trials.

Repurposing anti-HCV nucleosides against other positive-strand RNA viruses

Several important and sometimes severe human diseases are caused by RNA viruses in the Flaviviridae, Picornaviridae, Caliciviridae, and Coronaviridae families. All these viruses contain a positive-strand RNA genome, and their RNA-dependent RNA polymerases share significant amino acid similarities based on sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis [54, 55]. Since HCV belongs to the Flaviviridae family, some of the nucleoside analogs originally developed against HCV would also be expected to inhibit related pathogens within the same family or even viruses in other positive-strand RNA families. This prediction was confirmed by counter-screening anti-HCV molecules against representative panels of viruses from other families and sub-families (Table 1 ). In particular, 2′C-modified nucleosides are known to inhibit multiple positive-strand RNA virus families. In one of the first reported examples, 2′C-methyl-cytidine was found to be potent in cell-based in vitro assays against flaviviruses such as West Nile, yellow fever, and dengue virus [56]. This result is not entirely surprising since the same molecule was already known to inhibit BVDV, which also belongs to the Flaviviridae family, and was used as a surrogate for HCV antiviral screening. In an in vivo efficacy model, 2′C-methyl-cytidine protected hamsters challenged with a lethal dose of yellow fever virus even when administered up to 3 days post-infection [57]. The cytidine analog also inhibits the in vitro replication of tick-borne, hemorrhagic fever-associated flaviviruses [58]. In addition, 2′C-methyl-cytidine inhibits the replication of the Norwalk virus [59, 60] and foot-and-mouth disease virus [61] from the Caliciviridae and Picornaviridae family, respectively. Although it has not been as extensively profiled, the purine analog 7-deaza-2′C-methyl-adenosine similarly displays broad antiviral activity against positive-strand RNA viruses, while being inactive against single-strand negative-sense RNA viruses [27••, 28]. This broad spectrum activity was further profiled with the chemically related 7-deaza-2′C-ethynyl-adenosine. Although it was found to also inhibit HCV, the molecule was potent enough to be developed specifically against dengue virus infection [62, 63•]. To date, it is the only nucleoside analog known to inhibit dengue virus replication in a mouse efficacy model [63•]. However, its safety profile was insufficient to enable further drug development toward human clinical trials. On the basis of the finding that 4′-azido cytidine was potent against dengue virus replication in vitro, the ester prodrug, balipiravir, was also repurposed toward treatment of dengue virus infection [64]. For reasons that remain to be clarified, the drug did not reduce either viral load or symptoms when administered to hospitalized dengue-infected patients.

Table 1.

Inhibition of positive-strand RNA viruses by nucleoside analogs

| Inhibitor | Virus | Family | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2′C-Methyl-cytidine | Yellow fever | Flaviviridae | [56] |

| Kyasanur Forest disease | Flaviviridae | [58] | |

| Norwalk | Caliciviridae | [59, 60] | |

| Foot-and-mouth disease | Picornaviridae | [61] | |

| 7-Deaza-2′C-methyl-adenosine | Dengue, yellow fever, West Nile | Flaviviridae | [27••, 28] |

| Rhinovirus types 2, 3, 14 | Picornaviridae | [27••, 28] | |

| 7-Deaza-2′-ethynyl-adenosine | Dengue, yellow fever, West Nile | Flaviviridae | [62, 63•] |

| Balipiravir/4′-azido-cytidine | Dengue | Flaviviridae | [64] |

Challenges for discovering novel nucleoside analogs targeting positive-strand RNA viruses other than HCV

Although many anti-HCV nucleoside analogs may potentially inhibit other positive-strand RNA viruses in vitro, there are currently no obvious drug candidates for direct repurposing from HCV infection to other disease indications. In particular, sofosbuvir, the only FDA-approved anti-HCV nucleotide analog, is a phosphoramidate prodrug that has been optimized to specifically deliver high levels of the nucleoside 5′-triphosphate as the active species through release of the prodrug moiety by first-pass effect, the process by which drugs get metabolized into the liver before reaching systemic circulation [65]. Therefore, the active metabolite of sofosbuvir is likely not significantly distributed to organs and tissues other than the liver and targeted by most positive-strand RNA viruses. In comparison, 2′C-methyl-cytidine and 7-deaza-2′C-ethynyl-adenosine are among the only known broad-spectrum nucleoside analogs with potential for systemic organ exposure of the 5′-monophosphate and 5′-triphosphate forms in levels sufficient to achieve in vivo efficacy. However, their relatively poor safety profiles and narrow dose margins make them poor candidates for further clinical development.

What are the main challenges to designing and optimizing new inhibitors of non-HCV positive-strand RNA viruses? The search for such molecules has been hampered by several factors, the first one being the need to achieve in vivo pharmacokinetic properties compatible with delivery of the NTP to the site of infection, which differs by virus and includes, for example, the GI tract (Norwalk virus), the lungs (rhinovirus, Middle East respiratory syndrome virus), the brain (West Nile virus), and lymphoid organs (dengue virus). As mentioned before, the only organ-specific prodrugs that have been successfully developed to date for nucleosides target the liver, and will likely not be useful for non-liver infections. The second important limitation to finding new nucleoside analogs is also related to 5′-triphosphate formation and the choice of the immortalized cell lines used for in vitro infection experiments. The metabolic kinase activation pathways of many common laboratory strains and species of cell lines differ from natural human tissues or human primary cells. Although this is not generally a problem for small molecule drug testing, the metabolic activation of nucleoside analogs to NTPs entirely relies on the presence of specific nucleoside and nucleotide kinases that are sometimes deficient in common lab-adapted cell lines. Finally, it will be important to thoroughly assess the selectivity and toxicity of new nucleoside analogs to ensure that they do not interfere with cellular mechanisms at efficacious doses. In the case of acute infections, the safety requirements for short-term treatments may differ from those of anti-HCV nucleotides. Despite these challenges, the prospect of using nucleoside analogs to treat acute infections caused by RNA viruses represents an important paradigm shift and a new frontier for future antiviral therapies.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank Peggy Korn for her editorial review of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jerome Deval, Email: jdeval@aliosbiopharma.com.

Leo Beigelman, Email: lbeigelman@aliosbiopharma.com.

References

- 1.Moradpour D., Penin F., Rice C.M. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:453–463. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen D.M. A new era of hepatitis C therapy begins. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1272–1274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1100829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeuzem S., Andreone P., Pol S., Lawitz E., Diago M. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deval J., Huber M. 2014. Hepatitis C Virus and its Inhibitors: The Polymerase as a Target for Nucleoside and Nucleotide Analogs. Cancer-causing Viruses and Their Inhibitors; pp. 41–84. Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- 5••.Lesburg C.A., Cable M.B., Ferrari E., Hong Z., Mannarino A.F. Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from hepatitis C virus reveals a fully encircled active site. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:937–943. doi: 10.1038/13305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Together with Bressanelli et al. [7••], this study reports the first crystal structure of HCV NS5B showing that the polymerase is in a closed fingers conformation that serves to encircle the enzyme active site.

- 6.Ago H., Adachi T., Yoshida A., Yamamoto M., Habuka N. Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. Structure. 1999;7:1417–1426. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Bressanelli S., Tomei L., Roussel A., Incitti I., Vitale R.L. Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13034–13039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Together with Lesburg et al. [5••], this study reports the first crystal structure of HCV NS5B showing that the polymerase is in a closed fingers conformation that serves to encircle the enzyme active site.

- 8.Caillet-Saguy C., Simister P.C., Bressanelli S. An objective assessment of conformational variability in complexes of hepatitis C virus polymerase with non-nucleoside inhibitors. J Mol Biol. 2011;414:370–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9•.Chinnaswamy S., Yarbrough I., Palaninathan S., Kumar C.T., Vijayaraghavan V. A locking mechanism regulates RNA synthesis and host protein interaction by the hepatitis C virus polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20535–20546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801490200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes how the opening between the fingers and thumb sub-domain favors primer extension.

- 10.Scrima N., Caillet-Saguy C., Ventura M., Harrus D., Astier-Gin T. Two crucial early steps in RNA synthesis by the hepatitis C virus polymerase involve a dual role of residue 405. J Virol. 2012;86:7107–7117. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00459-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong Z., Cameron C.E., Walker M.P., Castro C., Yao N. A novel mechanism to ensure terminal initiation by hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase. Virology. 2001;285:6–11. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.Maag D., Castro C., Hong Z., Cameron C.E. Hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5B) as a mediator of the antiviral activity of ribavirin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46094–46098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First transient kinetic study with HCV NS5B showing how deletion of the β-hairpin loop enables the polymerase to readily extend a primer.

- 13.Ranjith-Kumar C.T., Gutshall L., Sarisky R.T., Kao C.C. Multiple interactions within the hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase repress primer-dependent RNA synthesis. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:675–685. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00613-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosley R.T., Edwards T.E., Murakami E., Lam A.M., Grice R.L. Structure of hepatitis C virus polymerase in complex with primer-template RNA. J Virol. 2012;86:6503–6511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00386-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamyatkin D.F., Parra F., Alonso J.M., Harki D.A., Peterson B.R. Structural insights into mechanisms of catalysis and inhibition in Norwalk virus polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7705–7712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Jin Z., Leveque V., Ma H., Johnson K.A., Klumpp K. Assembly, purification, and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of active RNA-dependent RNA polymerase elongation complex. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:10674–10683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.325530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Describes a method to isolate a stable NS5B-RNA elongation complex.

- 17.Powdrill M.H., Tchesnokov E.P., Kozak R.A., Russell R.S., Martin R. Contribution of a mutational bias in hepatitis C virus replication to the genetic barrier in the development of drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20509–20513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105797108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walton E., Holly F.W., Boxer G.E., Nutt R.F. 3′-Deoxynucleosides. IV. Pyrimidine 3′-deoxynucleosides. J Org Chem. 1966;31:1163–1169. doi: 10.1021/jo01342a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beigelman L.N., Ermolinsky B.S., Gurskaya G.V., Tsapkina E.N., Karpeisky M. A new synthesis of 2′-C-methylnucleosides starting from d-ribose. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1987:41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savochkina L.P., Sviriaeva T.V., Beigel’man L.N., Padiukova N., Kuznetsov D.A. Substrate properties of C′-methylnucleoside triphosphates in a reaction of RNA synthesis catalyzed by Escherichia coli RNA-polymerase. Mol Biol (Mosk) 1989;23:1700–1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buckwold V.E., Beer B.E., Donis R.O. Bovine viral diarrhea virus as a surrogate model of hepatitis C virus for the evaluation of antiviral agents. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll SS, LaFemina R, Hall DL, Himmelberger AL, Kuo LC, et al.: Nucleoside derivatives as inhibitors of RNA-dependent RNA viral polymerase. Patent number WO/2002/057425; 2002.

- 23.Sommadossi JP, La Colla P: Methods and compositions for treating hepatitis C virus. Patent number WO/2001/090121; 2001.

- 24.Sommadossi JP, La Colla P: Methods and compositions for treating flaviviruses and pestiviruses. Patent number WO/2001/092282; 2001.

- 25.Standring D.N., Lanford R., Wright T., Chung R.T., Bichko V. NM 283 has potent antiviral activity against genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV-1) infection in the chimpanzee. J Hepatol. 2003;38:3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poordad F., Lawitz E.J., Gitlin N., Rodriguez-Torres M., Box T. Efficacy and safety of valopicitabine in combination with pegylated interferon-alpha (pegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46:866A. [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Carroll S.S., Tomassini J.E., Bosserman M., Getty K., Stahlhut M.W. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus RNA replication by 2′-modified nucleoside analogs. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11979–11984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report describes the identification of 2′-substituted nucleosides as inhibitors of HCV replication. The study sets the basis for anti-HCV nucleoside discovery by establishing a correlation between inhibition potency of the NTP analogs against HCV polymerase, amount of intracellular NTP formation, and potency of the parent nucleoside in the replicon assay.

- 28.Olsen D.B., Eldrup A.B., Bartholomew L., Bhat B., Bosserman M.R. A 7-deaza-adenosine analog is a potent and selective inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication with excellent pharmacokinetic properties. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3944–3953. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3944-3953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll S.S., Ludmerer S., Handt L., Koeplinger K., Zhang N.R. Robust antiviral efficacy upon administration of a nucleoside analog to hepatitis C virus-infected chimpanzees. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:926–934. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01032-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dutartre H., Bussetta C., Boretto J., Canard B. General catalytic deficiency of hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase with an S282T mutation and mutually exclusive resistance towards 2′-modified nucleotide analogues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:4161–4169. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00433-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludmerer S.W., Graham D.J., Boots E., Murray E.M., Simcoe A. Replication fitness and NS5B drug sensitivity of diverse hepatitis C virus isolates characterized by using a transient replication assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2059–2069. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.2059-2069.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Migliaccio G., Tomassini J.E., Carroll S.S., Tomei L., Altamura S. Characterization of resistance to non-obligate chain-terminating ribonucleoside analogs that inhibit hepatitis C virus replication in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49164–49170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Maag H., Rydzewski R.M., McRoberts M.J., Crawford-Ruth D., Verheyden J.P. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of 4′-azido- and 4′-methoxynucleosides. J Med Chem. 1992;35:1440–1451. doi: 10.1021/jm00086a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First synthesis of 4′-azido-cytidine aimed to inhibit HIV as an analog of AZT. This molecule will later be identified as a potent inhibitor of HCV.

- 34.Klumpp K., Leveque V., Le Pogam S., Ma H., Jiang W.R. The novel nucleoside analog R1479 (4′-azidocytidine) is a potent inhibitor of NS5B-dependent RNA synthesis and hepatitis C virus replication in cell culture. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3793–3799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Pogam S., Jiang W.R., Leveque V., Rajyaguru S., Ma H. In vitro selected Con1 subgenomic replicons resistant to 2′-C-methyl-cytidine or to R1479 show lack of cross resistance. Virology. 2006;351:349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts S.K., Cooksley G., Dore G.J., Robson R., Shaw D. Robust antiviral activity of R1626, a novel nucleoside analog: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2008;48:398–406. doi: 10.1002/hep.22321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson D.R., Zeuzem S., Andreone P., Ferenci P., Herring R. Balapiravir plus peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kD)/ribavirin in a randomized trial of hepatitis C genotype 1 patients. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:15–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klumpp K., Kalayanov G., Ma H., Le Pogam S., Leveque V. 2′-Deoxy-4′-azido nucleoside analogs are highly potent inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication despite the lack of 2′-alpha-hydroxyl groups. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2167–2175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGuigan C., Kelleher M.R., Perrone P., Mulready S., Luoni G. The application of phosphoramidate ProTide technology to the potent anti-HCV compound 4′-azidocytidine (R1479) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:4250–4254. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith D.B., Kalayanov G., Sund C., Winqvist A., Maltseva T. The design, synthesis, and antiviral activity of monofluoro and difluoro analogues of 4′-azidocytidine against hepatitis C virus replication: the discovery of 4′-azido-2′-deoxy-2′-fluorocytidine and 4′-azido-2′-dideoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine. J Med Chem. 2009;52:2971–2978. doi: 10.1021/jm801595c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith D.B., Martin J.A., Klumpp K., Baker S.J., Blomgren P.A. Design, synthesis, and antiviral properties of 4′-substituted ribonucleosides as inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication: the discovery of R1479. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:2570–2576. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42••.Arnold J.J., Sharma S.D., Feng J.Y., Ray A.S., Smidansky E.D. Sensitivity of mitochondrial transcription and resistance of RNA polymerase II dependent nuclear transcription to antiviral ribonucleosides. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003030. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Comprehensive evaluation of 2′-C-methyl, 4′-methyl and 4′-azido anti-HCV ribonucleotide analogues as substrates for human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. This study establishes a link between human mitochondrial RNA polymerase as an off-target for ribonucleotide analogs and adverse effects resulting from mitochondrial toxicity observed in recent anti-HCV clinical trials.

- 43.Stuyver L.J., McBrayer T.R., Whitaker T., Tharnish P.M., Ramesh M. Inhibition of the subgenomic hepatitis C virus replicon in huh-7 cells by 2′-deoxy-2′-fluorocytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:651–654. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.2.651-654.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuyver L.J., McBrayer T.R., Tharnish P.M., Clark J., Hollecker L. Inhibition of hepatitis C replicon RNA synthesis by beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine: a specific inhibitor of hepatitis C virus replication. Antiviral Chem Chemother. 2006;17:79–87. doi: 10.1177/095632020601700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45•.Ma H., Jiang W.R., Robledo N., Leveque V., Ali S. Characterization of the metabolic activation of hepatitis C virus nucleoside inhibitor beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine (PSI-6130) and identification of a novel active 5′-triphosphate species. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29812–29820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study shows that 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-uridine is the deaminated metabolic product of 2′-fluoro-2′C-methyl-cytidine. The corresponding phosphorylated uridine species was identified in primary hepatocytes, and shown to be a potent inhibitor of HCV NS5B.

- 46.Murakami E., Niu C., Bao H., Micolochick Steuer H.M., Whitaker T. The mechanism of action of beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methylcytidine involves a second metabolic pathway leading to beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-2′-C-methyluridine 5′-triphosphate, a potent inhibitor of the hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:458–464. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01184-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furman P.A., Lam A.M., Murakami E. Nucleoside analog inhibitors of hepatitis C viral replication: recent advances, challenges and trends. Future Med Chem. 2009;1:1429–1452. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sofia M.J., Bao D., Chang W., Du J., Nagarathnam D. Discovery of a beta-d-2′-deoxy-2′-alpha-fluoro-2′-beta-C-methyluridine nucleotide prodrug (PSI-7977) for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7202–7218. doi: 10.1021/jm100863x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fung A., Jin Z., Dyatkina N., Wang G., Beigelman L. Efficiency of incorporation and chain termination determines the inhibition potency of 2′-modified nucleotide analogs against HCV polymerase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(7):3636–3645. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02666-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Clercq E. Current race in the development of DAAs (direct-acting antivirals) against HCV. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;89:441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sofia M.J., Chang W., Furman P.A., Mosley R.T., Ross B.S. Nucleoside, nucleotide, and non-nucleoside inhibitors of hepatitis C virus NS5B RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase. J Med Chem. 2012;55:2481–2531. doi: 10.1021/jm201384j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chapron C., Glen R., La Colla M., Mayes B.A., McCarville J.F. Synthesis of 2′-O,4′-C-alkylene-bridged ribonucleosides and their evaluation as inhibitors of HCV NS5B polymerase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:2699–2702. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Girijavallabhan V, Njoroge FG, Bogen S, Verma V, Bennett F, et al.: 2′-Substituted nucleoside derivatives and methods of use thereof for the treatment of viral diseases. Patent number WO/2012/142085; 2012.

- 54.Koonin E.V. The phylogeny of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of positive-strand RNA viruses. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(Pt 9):2197–2206. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Te Velthuis A.J. Common and unique features of viral RNA-dependent polymerases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1695-z. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benzaria S., Bardiot D., Bouisset T., Counor C., Rabeson C. 2′-C-Methyl branched pyrimidine ribonucleoside analogues: potent inhibitors of RNA virus replication. Antiviral Chem Chemother. 2007;18:225–242. doi: 10.1177/095632020701800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Julander J.G., Jha A.K., Choi J.A., Jung K.H., Smee D.F. Efficacy of 2′-C-methylcytidine against yellow fever virus in cell culture and in a hamster model. Antiviral Res. 2010;86:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flint M., McMullan L.K., Dodd K.A., Bird B.H., Khristova M.L. Inhibitors of the tick-borne, hemorrhagic fever-associated flaviviruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3206–3216. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02393-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rocha-Pereira J., Jochmans D., Dallmeier K., Leyssen P., Cunha R. Inhibition of norovirus replication by the nucleoside analogue 2′-C-methylcytidine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rocha-Pereira J., Jochmans D., Debing Y., Verbeken E., Nascimento M.S. The viral polymerase inhibitor 2′-C-methylcytidine inhibits Norwalk virus replication and protects against norovirus-induced diarrhea and mortality in a mouse model. J Virol. 2013;87:11798–11805. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02064-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lefebvre D.J., De Vleeschauwer A.R., Goris N., Kollanur D., Billiet A. Proof of concept for the inhibition of foot-and-mouth disease virus replication by the anti-viral drug 2′-C-methylcytidine in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1111/tbed.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Latour D.R., Jekle A., Javanbakht H., Henningsen R., Gee P. Biochemical characterization of the inhibition of the dengue virus RNA polymerase by beta-d-2′-ethynyl-7-deaza-adenosine triphosphate. Antiviral Res. 2010;87:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63•.Yin Z., Chen Y.L., Schul W., Wang Q.Y., Gu F. An adenosine nucleoside inhibitor of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20435–20439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Proof-of-concept study demonstrating in vivo efficacy of a ribonucleoside analog against dengue virus. To date, it is the only nucleoside analog known to inhibit dengue virus replication in a mouse efficacy model.

- 64.Nguyen N.M., Tran C.N., Phung L.K., Duong K.T., Huynh Hle A. A randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial of balapiravir, a polymerase inhibitor, in adult dengue patients. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1442–1450. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGuigan C., Madela K., Aljarah M., Bourdin C., Arrica M. Phosphorodiamidates as a promising new phosphate prodrug motif for antiviral drug discovery: application to anti-HCV agents. J Med Chem. 2011;54:8632–8645. doi: 10.1021/jm2011673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]