Abstract

Stress necessitates rapid reprogramming of translation in order to facilitate an adaptive response and promote survival. Cytoplasmic stress granules (SGs) and processing bodies (PBs) are dynamic structures that form in response to stress-induced translational arrest. PBs are linked to mRNA silencing and decay, while SGs are more closely linked to translation and the sorting of specific mRNAs for different fates. While they share some components and can interact physically, SGs and PBs are regulated independently, house separate functions, and contain unique markers. SG formation is associated with numerous disease states, and the expanding list of SG-associated proteins integrates SG formation with other processes such as transcription, splicing, and survival. Growing evidence suggests that SG assembly is initiated by translational arrest, and mediates cross talk with many other signaling pathways.

Keywords: Stress granules, Processing bodies, GW bodies, eIF2α, Translational silencing, Argonaute, G3BP, GW182, TIA-1, Polysomes

I. Introduction

Nuclear DNA is packaged into chromatin, organized into active and inactive domains, and its availability is regulated by the many factors that control its access to polymerases, splicing factors, and the nuclear periphery. In the cytoplasm, RNA is similarly structured, organized, and regulated by interactions with membranes, the cytoskeleton, different organelles, and by a host of aggregation-prone RNA-binding proteins. Localized gradients of specific mRNA transcripts regulate the organization and the timing of gene expression that occurs during development. Within individual somatic and germ cells, discrete mRNA granules are transiently assembled as mRNA transcripts move into and out of polysomes. The recruitment, retention, and removal of specific transcripts into and out of RNA granules is orchestrated by numerous mRNA binding proteins, which regulate the fate of specific transcripts.

Consequently, biochemical analysis of protein translation in cell lysates cannot completely recapitulate the translational regulatory pathways that occur in live cells. Critical components of the “cell biology” of protein translation are mRNP granules known as processing bodies (PBs) and stress granules (SGs). These transient cytoplasmic “structures” are actively assembled from untranslated mRNA by a host of RNA-binding proteins, which determine whether specific transcripts will be reinitiated, degraded, or stored. The mRNA within PBs and SGs is in a dynamic equilibrium with polysomes, and this equilibrium is shifted by changes in environmental conditions. Specific RNA-binding proteins promote the translation of some transcripts and inhibit the translation of others; silenced transcripts are assembled into SGs or PBs, whereas preferential translation occurs outside these bodies. In stressed cells, the selective translational repression of “housekeeping” genes conserves anabolic energy for the repair of stress-induced molecular damage. At the same time, enhanced translation of repair enzymes directly repairs this damage while promoting an adaptive response to the altered conditions. Thus, shifting specific transcripts between polysomes and RNA granules tailors translation to changes in environmental conditions.

SGs and PBs are dynamic structures that are continuously assembled/disassembled from the flux of mRNPs that comprise them. Drugs that arrest translational elongation and thereby stabilize polysomes promote the disassembly of SGs and PBs, whereas drugs that enhance polysome disassembly promote (but are not sufficient to cause) SG/PB assembly. Numerous photobleaching studies indicate that the mRNPs that comprise SGs and PBs are in very rapid flux (seconds), although SGs and PBs persist for minutes to hours. A useful analogy holds that mRNPs are to SG/PBs as water is to a river; rapidly moving water creates a large stable river, but the water is always in flux. Similarly, moving streams of mRNPs create SGs and PBs. When examining the functional properties of SG/PBs, it is useful to consider that the functional properties of rivers (e.g., erosion, navigation, and hydroelectric power) are different from those of water alone. Similarly, the discrete domains (SGs and PBs) created from relocalized mRNPs alter the trafficking of other proteins and have important secondary effects (alternative splicing, transcription, nucleocytoplasmic transport) on overall cell metabolism.

II. Early History of Stress Granules

In 1999, it was noted that stress-induced translational arrest causes untranslated mRNPs to assemble into large cytoplasmic “SGs,” whose formation is triggered by, and dependent upon, the phosphorylation of eIF2α.1 These granules contain a large proportion of cytoplasmic poly(A) mRNA and PABP, suggesting that most of the cytoplasmic polyA(+) mRNA is assembled into the granules upon stress. Remarkably, the normally nuclear RNA-binding protein TIA-1 (T-cell internal antigen 1) rapidly colocalizes in these cytoplasmic granules, and a truncation mutant of TIA-1 blocks their formation. As similar RNA-containing “heat-shock granules” had been described in plant cells,2 it seemed likely that mammalian SGs were related to plant “heat-shock granules.” Only recently3 was it shown that RNA-containing SGs and plant heat-shock granules are in fact distinct: plant heat-shock granules do not contain mRNA as originally reported, although plant cells do indeed form bona fide SGs and PBs in addition to heat-shock granules. Thus in hindsight, and despite the frequent use of the phrase “it has long been known” to describe RNA-containing SGs, in actual fact these SGs were first described only a decade ago.

SGs were then demonstrated to be dynamic sorting centers rather than stable repositories of mRNA, as their apparent identity with plant heat-shock granules had predicted.4 Pharmacological data revealed that SG assembly is blocked by agents that arrest translation elongation (e.g., emetine and cycloheximide), but not by agents that promote translation termination (e.g., puromycin), indicating that polysome disassembly is required for SG assembly. Importantly, preassembled SGs are forcibly disassembled by emetine even in the continued presence of phospho-eIF2α suggesting that they do not represent static storage depots of mRNPs but instead contain mRNPs in equilibrium with polysomes. Direct measurements using FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) confirmed that both TIA-1 and PABP rapidly shuttle into and out of SGs, with TIA-1 moving more rapidly than PABP. The half-lives revealed by FRAP were on the order of 2–10 s, in marked contrast with the much slower kinetics of SG assembly (15–30 min). The first movies of SG assembly and disassembly revealed that SGs form synchronously throughout the cell and progressively fuse to become larger and fewer. As cells recover from stress, the large “mature” SGs disassemble synchronously within individual cells, in a time frame of 4–6 min. These data established that SGs are dynamic microdomains into which PABP and TIA-1 rapidly shuttle, and which are in equilibrium with polysomes. PABP is a translational enhancer, and TIA-1 is a translational silencer,5 hence we proposed that SGs constitute dynamic mRNA triage domains, in which mRNA processing, sorting, and remodeling events regulate the expression of specific transcripts.6, 7

A more detailed in situ analysis of SGs8 revealed that they contain small but not large ribosomal subunits, and the initiation factors eIF3, eIF4E, and eIF4G. However, eIF5 and eIF2 are not prominent components of SGs, despite the fact that phospho-eIF2α drives SG assembly. Contemporary models of translation initiation suggested that eIF5 normally links eIF2/GTP/tRNAMeti to eIF3 and the small ribosomal subunit to form the 43S complex, which is thought to form prior to the recruitment of eIF4F, PABP, and the mRNA to form the 48S complex. As SGs contain most components of the 48S complex but lack eIF5 and eIF2, SGs appear to contain aggregates of aberrant 48S complexes, lacking eIF5/eIF2/GTP/tRNAMeti but containing instead the TIA proteins. In sucrose gradients, these TIA-1-containing complexes migrate with small mRNPs near the top of the gradient rather than with polysomes. Interestingly, phospho-eIF2α is detected in late SGs, but not newly formed ones, supporting a model in which lack of ternary complexes drives SG formation via the formation of aberrant 48S complexes. Another report9 partly confirmed these results, but differed in finding eIF2α and eIF2B in arsenite-induced SGs: whether this reflects differences between antibodies or cell lines remains unresolved. This study showed for the first time that thapsigargin, a specific activator of PERK, induces SGs that are prevented by a kinase-dead form of PERK. Together, these studies established that SG formation is a result of stalled initiation and confirmed a central role for phospho-eIF2α in their assembly.

In 2003, it was shown that another RNA-binding protein, Ras-Gap binding protein 3 (G3BP), is a SG component whose overexpression nucleates SG assembly, and that this ability is linked to the phosphorylation of a specific G3BP serine residue.10 G3BP is a multifunctional protein linked to numerous pathways,11 and its ability to nucleate dynamic (e.g., cycloheximide-reversible) SGs has subsequently been widely exploited in the field to study SG composition. Although originally described as an endonuclease, no such activity has been demonstrated in vivo, so the functional consequences of G3BP-nucleated SGs are unknown. However, the AU-rich mRNA decay factor tristetraprolin (TTP) similarly nucleates SGs which are prevented by its phosphorylation and interactions with 14-3-3 proteins,12 providing the first example of a protein that moves to SGs under some conditions but not others. A flood of proteins too numerous to cite individually were subsequently identified as SG-associated (summarized in Table I ). Some of these are considered below.

Table I.

SG and PB Associated Proteins

| Protein | SG/PB localization | References | Nucleation | Knockdown effects on SGs or PBs | Function | Location | SG/PB partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ago1 | PBs and SGs | 76, 77 | SGs and PBs | None | Gene silencing | Cyt | GW182 |

| Ago2 | PBs and SGs | 52, 76, 77 | SGs and PBs | None | siRNA, slicer | Cyt | FXR1, GW182, PACT |

| AKAP350A | SGs | 48 | KD reduces SG size | Protein scaffold | Cyt, Golgi | Caprin-1, CCAR, G3BP | |

| APOBEC1 | SGs not PBs | NK, PA | RNA editing | Cyt | |||

| APOBEC3G | SGs and PBs | 63, 78, 79 | No | Cytidine deaminase, antiviral | Cyt | ||

| Ataxin-2 | SGs not PBs | 80 | No | KD reduces SGs | Translation | Cyt | PABP |

| Calreticulin | SGs | 81 | Cyt, ER | arginine-modified | |||

| CCAR1 | SGs | 48 | KD reduces SGs | Transcriptional coactivator | Nuc>Cyt | AKAP350, wnt signaling | |

| CCR4 | PBs | 19 | Transcription, ribosome biogenesis | Cyt | 10 protein complex | ||

| Caprin-1 | SGs | 82 | Yes | KD reduces SGs | Cell cycle | Cyt>Nuc | G3BP |

| CIRP | SG | 83, 84 | Yes | Translational silencer | Nuc>Cyt | ||

| CPEB1 | SGs and PBs | 37 | Yes | Translational silencer | Cyt | ||

| DAP5 | SGs | 85 | Translation | Cyt | |||

| DBPA | SG | 66 | Splicing | Nuc>Cyt | |||

| DCP1 | PBs not SGs | 35 | No | mRNA Decay | Cyt | Hedls | |

| DCP2 | PBs not SGs | 35 | No | mRNA decay | Cyt | ||

| DDX1 | SGs | 86 | ds DNA breaks, UV | Nuc>Cyt | |||

| DDX3 | SGs | 87, 88 | RNA helicase | Shuttles | |||

| DIS 1 | SGs | 89 | Overexpressed only | Cyt | eIF3 | ||

| DLC2a (dyein LC2A) | SGs | 40 | KD reduces SGs | Cyt | TIA-1, HuR | ||

| edc1,2 | PBs | 90 | mRNA decay | Cyt | |||

| edc3 | PBs | 91 | Cyt | ||||

| eIF1 | SGs not PBs | NK, PA | Translation initiation | Cyt | |||

| eIF2α | Variable at SGs | 8, 9 | S51D mutant nucleates SGs | S51A mutant inhibits | Translation initiation | Cyt>Nuc | |

| eIF3 | SGs not PBs | 8 | eIF3p48 nucleates SGs; eIF3p44 inhibits SGs | Translation initiation | Cyt | ||

| eIF4A, B | SGs only | 13 | No | RNA helicase, translation | Cyt>nuc | ||

| eIF4E | SGs and PBs | 35 | No | Translation, cap binding | Cyt>nuc | ||

| eIF4G | SG not PBs | 35 | Translation initiation | Cyt | |||

| eIF4E-T | PBs not SGs | 92 | No | mRNA decay | Cyt | ||

| eIF4H | SGs not PBs | NK/PA | Translation | Cyt | |||

| EWS | SGs | 92 | SGs | Oncogene | Nuc>cyt | ||

| FAK | SGs | 93 | Motility, signaling | Cyt | |||

| FAST | PBs, SGs | 35 | SGs and PBs | No effect | Signaling | Nuc, cyt | |

| FMRP/FXR1 | SGs not PBs | 69, 70, 94 | SGs | KD reduces SG | Translation, splicing, microRNA | Cyt>nuc | |

| FBP/KSRP | SGs | 83 | KH3-domain nucleates SGs | mRNA decay, miRNA processing | Nuc>cyt | ||

| FUS | SGs | 95 | SGs | Motility | N>cyt | ||

| GRB7 | SGs | 93 | Protein scaffold | Cyt | |||

| GW182, TNRC6B | PBs, not SGs | 96 | No | KD bk PB | siRNA | Cyt | |

| G3BP | SGs not PBs | 10, 35 | SGs | S149E mutant reduces SGs | Helicase, protein scaffold | Nuc>cyt, shuttles | Caprin1, USP10 |

| HDAC6 | SGs not PBs | 41 | No | Truncation reduces SGs | Deacetylase, stress signaling | Cyt | |

| Hedls/Ge-1 | PBs not SGs | 91, 97 | PBs | Enhances mRNA decapping | Cyt | ||

| hnRNP A1 | SGs | 44 | No | Splicing, multifunctional | Nuc>cyt | ||

| hnRNP A3 | PBs not SGs | 98 | Splicing, multifunctional | Nuc>cyt | NXF7 | ||

| hnRNP K | SGs | 99 | No | mRNA processing | Nuc>cyt | RBM42 | |

| hnRNPQ | SGs (and PBs?) | 100 | Splicing | Nuc>cyt | APOBEC1 | ||

| HSP27 | SGs (HS) | 101 | Heat shock | Cyt>nuc | |||

| HSP90 | SGs not PBs | 52 | Inactivation reduces PBs | Molecular chaperone | |||

| HuR | SGs or PBs | 102 | No | Stability, splicing | Nuc>cyt | ||

| Importin 8 | PBs and SGs | 103 | No | Shuttling | |||

| IP5K Ins (1,3,4,5,6)P5 2-kinase | SGs (GFP) | 104 | SGs | Protein scaffold, not a kinase | Shuttles | ||

| KSRP aka FUBP2 | SGs or PBs arg meth/SMN | 83 | microRNA proc, splicing, ARE stability | Nuc>cyt | 14-3-3 SMN | ||

| Lin28 | SGs and PBs, stem cells | 105 | Block let7 processing | Cyt>nuc, shuttles | |||

| Line1-ORFp | SGs | 66 | SGs | Transposon | |||

| Lsm1 | PBs>SGs | 106 | No | ||||

| MBNL1 | SGs | 86 | Alternative splicing | Nuc>cyt | |||

| hMEX-3B | SGs, PBs | 43 | SGs and PBs | Germline development | Shuttles | 14-3-3, Ago1 | |

| MLN51 | SGs | 26 | No | KD reduces SGs | EJC, splicing | ||

| MOV10/Armitage | PBs | 107 | RNA-directed transcription | ||||

| Musashi | SGs and PBs | 108 | No | PABP | |||

| NXF7 | PBs | 98 | PBs, SG | mRNA export | Nuc>cyt | hnRNPs, KSRP | |

| PABP | SGs not PBs | 1 | KD reduces SGs | Translation | Shuttles | ||

| p54/RCK | PBs and SGs | 37 | yes | Translation/decay | Cyt | ||

| P58 (TFL) | PBs not SGs | 109 | Cell-cycle control | ||||

| PACT | SGs | 52 | Loads RISC, PKR activator | Ago2, PKR | |||

| Pat1 | PBs | 110 | Decapping | Cyt | |||

| PAI-RBP1 | SGs | 66 | |||||

| PCP1. 2 (hnRNP E1,2) | SGs and PBs | 111 | IRES, neuronal granules | Nuc>cyt | |||

| Plakophillin1/3 | SGs | 111, 112 | No | Adhesion | Cyt | G3BP | |

| PMR1 | SGs | 113 | No | Endonuclease | Cyt | ||

| Pumilio 2 | SGs | 114 | Yes | KD reduces SG | Development | Nuc | |

| RACK1 | SGs | 39, 45 | Yes | Signaling, polarity | Cyt | ||

| Rap55/Lsm14 | SGs and PBs | 115 | No | KD reduces PBs | Cyt | ||

| RBM42 | SG not PB | 99 | No | Nuc>cyt | |||

| RHAU helicase | SGs | 88 | No | No | RNA helicase | Nuc>cyt | |

| RSK2 | SG | 46 | Kinase | Cyt | TIA-1 | ||

| Roquin | SGs and PBs | 72 | Yes-PBs? | E3 ligase | Cyt | ||

| Rpp20 | SGs | 116 | No | RNAse P subunit | |||

| Rpb4 (pol II subunit) | SGs | 117 | mRNA transcription | Nuc | |||

| SAM68 | SG subset | 118 | No mutant nucleates | Multifunction, alternative splicing | Nuc>cyt | ||

| SGNP | SGS | 119 | Ribosome maturation? | Nucleolar | |||

| SRC3 | SGs not PB | 47 | No | Transcriptional coactivator | Nuc>cyt | ||

| Smaug | SGs and PBs | 120 | SGs and PBs | Translational silencing | Cyt | ||

| Staufen | SGs | 121, 122 | No | KD promotes SGs. Overxpression reduces SGs | ds RNA binding | Cyt | |

| SMN | SGs | 123 | Yes | no | snRNP assembly | Nuc, cyt | |

| TAF15 | SGs | 95 | Yes | Oncogene | Nuc>cyt | ||

| TIA-1/TIAR | SGs>PBs | 1 | Yes | KD reduces SG | Splicing, translational silencer | Shuttles, Nuc>cyt | |

| TNRC6B (GW182 fam) | PBs | 107 | KD reduces PBs | microRNA silencing | |||

| TRAF-2 | SGs not PBs | 49 | No | No | Signaling | ||

| TTP/BRF-1 | SGs and PBs | 35, 73 | Yes | No | mRNA decay | Cyt>nuc, shuttles | |

| TUDOR-3 | SGs | 50, 51 | Binds FMRP | ||||

| TSN | SGs | 65 | No | Antiviral nuclease | G3BP | ||

| Ubiquitin | SGs | 41 | No | Signaling, protein turnover | Nuc>cyt | ||

| Xrn1 | PBs and SGs | 35 | Yes | mRNA decay | Cyt | ||

| YB-1 | SGs and PBs | 124 | mRNA chaperone | Nuc>cyt | |||

| ZBP1 (zipcode BP) | SGs | 125 | No | mRNA localization | |||

| ZBP1 (ZDNA BP) | SGs | 126 | Antiviral |

Nuc, nuclear localization; Cyt, cytoplasmic localization. NK/PA, unpublished.

“Nucleation” refers to the ability of an ectopically expressed protein to induce SG or PB assembly. KD, knockdown.

Importantly, a natural product isolated from New Zealand sponge, pateamine A, induces SGs compositionally similar to those induced by arsenite: these SGs contain eIF3, eIF4E, eIF4G, and TIA-1 but are assembled in the absence of eIF2α phosphorylation. Pull-down studies established that the molecular target of pateamine A is eIF4A,13 the DEAD-box helicase necessary for cap-dependent translation requiring 48S scanning. Toe-printing studies and polysome profiles on in vitro translated material revealed that pateamine A inactivates scanning, apparently by stabilizing interactions between eIF4A and eIF4B. This study added eIF4A and eIF4B to the growing list of initiation factors found in SGs. A similar compound named hippuristanol, found in the coral Isis hippuris, also blocks eIF4A scanning activity by preventing its binding to mRNA.14 Remarkably, both pateamine A and hippuristanol induce SGs in mutant eIF2α-S51A MEFs, which contain only a non-phosphorylatable form of eIF2α,15, 16 and the SGs induced by these drugs contain eIF2 and eIF5. These drugs have been widely used in subsequent studies to determine whether a given protein is recruited to SGs or not, and as such have been invaluable tools. However, these drugs circumvent the physiological stress response that activates one or some of the multiple kinases that target eIF2α (and perhaps other proteins: PKR targets RNA helicase A; Ref. 17) as well as other kinase cascades. Moreover, eIF4A is present in multiple isoforms and has other functions (e.g., NMD), and these drugs have other targets in addition to eIF4A (e.g., pateamine A binds unrip; Ref. 13).

The discovery that yeast18 and human cells19 contain dynamically organized sites of mRNA decay enzymes and proteins later recognized as part of the microRNA silencing machinery (reviewed in 20, 21, 22, 23) occurred somewhat later than the first SG studies. PBs exhibit similar dynamics and share some proteins with SGs, but are associated with mRNA decay rather than translation. While regulated mRNA decay is perhaps the ultimate form of translational control, this subject is beyond the scope of this chapter.

III. Stress Granules—Basic Attributes

SGs are absent from the cytoplasm of normally growing cells, but they are rapidly assembled in cells exposed to sudden changes in environmental conditions. In most cases, SG assembly results from stress-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α, a component of the eIF2/GTP/tRNAMeti ternary complex that directs tRNAi Met to the 40S ribosomal subunit. Phospho-eIF2α is a competitive inhibitor of eIF2B, a GDP-GTP exchange factor that charges the eIF2/GTP/tRNAMeti ternary complex. Thus, phosphorylation of eIF2α effectively depletes active ternary complex resulting in translational repression. This translation control pathway is initiated by a family of eIF2α kinases that are activated by different types of environmental stress. Protein kinase R (PKR) senses heat, UV irradiation, and viral infection.24, 25 PERK/PEK (PKR-like ER kinase) senses endoplasmic reticular stress accompanying excess production of secretory proteins; GCN2 (General Control non-derepressible 2) senses nutrient stress (e.g., amino acid starvation); HRI (Heme-regulated inhibitor) senses heme levels in erythroid progenitor cells to balance the synthesis of globin and heme, as well as arsenite-induced oxidative stress. Lack of ternary complex triggers SG assembly by stalling initiation while allowing elongation to proceed normally, resulting in polysome disassembly, necessary but not sufficient for both SG and PB assembly. Notably, PB formation is independent of phospho-eIF2α, although it still requires free mRNPs.

The specificity of stress-induced translational repression correlates with SG assembly. Whereas mRNAs encoding “housekeeping” transcripts are concentrated at SGs, mRNAs encoding molecular chaperones that refold stress-denatured proteins (HSP70) or alter the conformation of signaling proteins (HSP90) are selectively excluded from SGs. This has been proposed to account, in part, for the ability of certain transcripts to be selectively translated during stress. Although the mechanism by which HSP70 transcripts are excluded from SGs is not known, it is likely that mRNAs transcribed during stress acquire or lack distinct protein “marks” that determine their functional fate in the cytoplasm. HSP70 transcripts are unusual in several ways: they lack introns, and thereby lack proteins deposited at splicing junctions, one of which (MLN51) is selectively recruited to SGs26—whether this allows a selective recruitment of spliced mRNAs into SGs remains to be determined. In addition, HSP70 mRNA possesses a long structured 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) that allows translation initiation to occur via a shunting mechanism,27 which would preclude reliance on eIF4A, whose inactivation causes SG assembly.15, 16 As certain viral 5′-UTRs exempt transcripts from SG recruitment and translational silencing,28 the HSP70 5′-UTR may function similarly. A number of viral mRNAs elude or suppress SG assembly by various mechanisms.

Stress-activated translation of some transcripts is a consequence of upstream open reading frames (ORFs) found in the 5′-UTR. Under normal conditions, translation is initiated at the start codon of these ORFs, preventing ribosomes from initiating translation at the protein-encoding ORF. When stress-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α depletes the levels of ternary complex, initiation at the upstream ORFs becomes inefficient, allowing some initiation complexes to scan to the cryptic productive initiation codon. This mechanism allows stress-activated translation of ATF4, a key transcription factor that regulates the integrated stress response. Thus, eIF2α-induced SG formation correlates with enhanced translation of this class of transcripts.

Most environmental stimuli which induce SGs (arsenite, clotrimazole, heat shock, osmotic shock, thapsigargin, UV) increase levels of phospho-eIF2α, usually by activating a kinase and/or inactivating an eIF2α phosphatase. These stimuli do not induce SGs in mutant MEFs (S51A) expressing a nonphosphorylatable form of eIF2α, 29, 29a, 30 which have been invaluable in discriminating between phospho-eIF2α-dependent and phospho-eIF2α-independent mechanisms of SG induction. eIF2α-independent SGs can be induced through inactivation of eIF4A helicase activity (pateamine A, hippuristanol, the lipid anti-inflammatory mediator 15-PGJ2) which disrupts mRNA scanning (Table II ).

Table II.

Stress and Pharmacological Induces of SGs and PBs

| Drug | Mode of action | Effect on SGs | Effect on PBs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenite | Oxidative stressor, activates HRI, induces phosphorylation of eIF2α. Induces HSPs and GRPs | Strong inducer, SGs often adjacent to PBs | Strong inducer; PBs often adjacent to SGs |

| Clotrimazole | Inhibits Hexokinase II, causes energy starvation | Induces | No effect |

| Cycloheximide | Blocks elongation, activates SAPK | Blocks/disassembles | Blocks/disassembles |

| Edeine | Impairs initiation, blocks 60S joining | Induces | ? |

| Emetine | Blocks elongation, does not activate SAPK | Blocks/disassembles | Blocks/disassembles |

| FCCP | Mitochondrial poison, collapses proton gradient | Induces (CTS) | No effect/disassembles (CTS) |

| Heat shock | Protein denaturation, activates GCN2 | Induces | May induce, after SGs disperse |

| Hippuristanol | Inactivates eIF4A, impairs eIF4F/scanning | Induces | ? |

| MG132 | Inhibits chymotryptic proteases including proteasome, activates autophagy | Weakly induces (CTS) | No effect |

| Pateamine A | Inactivates eIF4A, impairs eIF4F/scanning | Induces | No effect |

| Puromycin | Promotes termination | Weakly induces | May enlarge |

| Sorbitol | Osmotic stress | Induces | No effect |

| Thapsigargin | ER stress, releases Ca2+ | Induces | No effect |

CTS, “cell type specific” effect occurs in some cell lines but not others.

SGs can be nucleated by ectopic expression of a wide range of SG-associated proteins (e.g., caprin1, G3BP1, FMRP/FXR1, TIA-1/TIAR; see Table I). These proteins induce the formation of compositionally typical SGs (containing mRNA, PABP, and initiation factors) and exhibit dynamic behavior: they are disassembled in response to cycloheximide or emetine, but not puromycin. To date, all tested nucleator proteins (G3BP, TIA-1/TIAR, TTP, FASTK, FMRP/FXR1) fail to nucleate SGs in the S51A mutant MEFs, so this type of SG induction is phospho-eIF2α dependent. Cotransfection of a PKR inhibitor usually prevents SG nucleation in wild-type cells, implicating PKR as the responsible kinase28. Most SG nucleators bind mRNA directly, and possess self-aggregation domains. In many cases, overexpression of the RNA-binding domains alone has no effect on SG dynamics, whereas overexpression of the aggregation domains can dominantly inhibit SG assembly. Deletion or knockdown of individual SG-nucleating proteins can have no effect, limit SG size, or delay SG assembly, or prolong SGs during recovery (Table I).

IV. Processing Bodies/EGP Bodies/SGs in Yeast

Much of our understanding of PBs comes from pioneering studies performed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae,21 but the situation in metazoans is complicated by (1) additional decapping proteins such as Hedls/GE-1, which are lacking in yeast23; (2) the fact that metazoan PBs also house the microRNA machinery and associated noncoding RNAs which are absent in budding yeast20; and (3) metazoan PBs contain many proteins (4ET, FAST, APOBEC3AG) also lacking in yeast. Moreover, yeast display a range of different dynamic granules that appear related, but may not be identical, to those in metazoans. Glucose starvation triggers the formation of yeast “EGP” bodies (containing eIF4E, eIF4G, and PABP) that exhibit dynamic behavior but lack eIF3 and 40S subunits.31, 32 These bodies contain other mRNA-binding proteins related to mammalian SG-associated proteins, and were referred to as “yeast SGs,”33 despite their lack of eIF3/40S and nonreliance on phospho-eIF2α for their formation. Recently, eIF3α/40S-containing “yeast SGs” have been described in S. cereviseae 34 exposed to robust heat shock, that require energy for their assembly but not phospho-eIF2α, and appear to contain the PB marker DCP2. Further studies and consistent definitions will be required to classify the yeast SGs/EGPBs/PBs before we can understand their function(s) and relevance to metazoan systems, especially given the historical confusion between plant heat-shock granules and metazoan SGs.

V. Metazoan PBs Versus GWBs

Unlike SGs, mammalian PBs are found in normally growing cells, in a cell-cycle-dependent manner. Whereas SGs are highly variable in size and shape, PBs are uniform, spherical structures that may exhibit directed movements within the cytoplasm. The signature components of PBs are deadenylases (CCR4), decapping enzymes (DCP1 and DCP2), decapping enhancers (Hedls/GE-1), and exonucleases (XRN1) that are required for 5′–3′ mRNA decay. PBs increase in size and number in cells lacking one or more components of the mRNA decay machinery,19 suggesting that mRNA accumulates in PBs while awaiting decay. The number of PBs found in the cytoplasm of normally growing cells varies among different cell lines: HeLa and COS exhibit higher basal levels of PBs than U2OS cells, most of which lack “resting” PBs entirely. PB number and size is increased several fold in response to some types of environmental stress (e.g., oxidative stress), however, in mammalian cells some stresses (heat shock, clotrimazole, glucose deprivation, etc.) induce SGs without inducing PBs,35 providing additional evidence that other independent signaling pathways regulate SG and PB assembly, beyond their dependence (SGs) or independence (PBs) on phospho-eIF2α.

Complicating the picture is the fact that mammalian PBs are usually, but not invariably, coincident with “GW bodies,” defined by the scaffolding proteins GW182, and housing components of the microRNA machinery, notably argonaute-2 (Ago‐2). Ago2 is recruited to SGs (here defined as containing eIF3), whereas GW182 appears largely restricted to PBs (defined as containing DCP1a or Hedls, which have not been reported to enter SGs). Whether the decapping machinery and the microRNA machinery share a common unidentified molecular link, or whether they are linked to some common cellular membrane or structure is not yet clear. Two nuclear structures linked to mRNP maturation and processing, Cajal bodies and Gems, are coincident in many but not all cell types, so there is precedent for this duality.36 This spatial confluence is ascribed to coupled mRNA processing or remodeling steps that tether these structures together. Factors regulating PB/GWB fusion have not been identified, although there are reports of PB heterogeneity. Interactions between SGs and PBs are more clearly documented.35, 37 Some conditions (arsenite, overexpression of TTP or CPEB) similarly cause SGs and PBs to juxtapose and fuse, whereas under other conditions they are largely independent. These regulated interactions between SGs and PBs suggest that mRNP components move from one type of granule to the other. This could indicate the degradation of untranslated transcripts passing through SGs into PBs, or the rescue of decay-bound mRNPs from PBs.

VI. SG Assembly—Mechanisms and Model

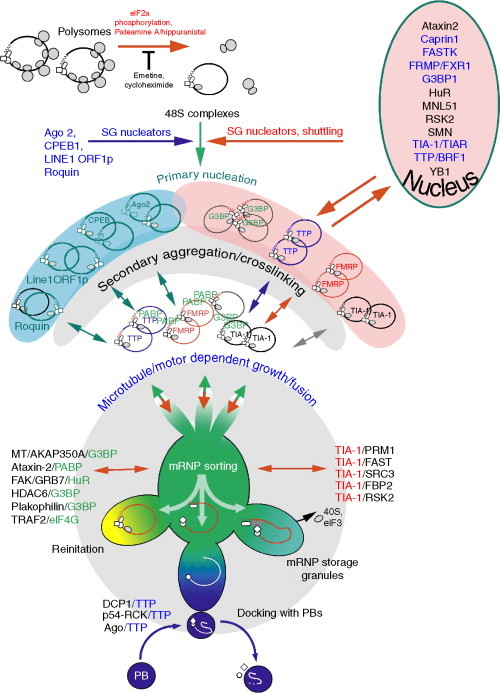

An evolving model of SG assembly is shown in Fig. 1 . It posits a series of reversible aggregation-driven stages, which allow for the rapid assembly and disassembly of SGs, as well as the inclusion or export of specific mRNPs to PBs, such as those containing TTP.

Fig. 1.

Model depicting the graded stages of SG assembly. Stalled initiation allows elongating ribosomes to leave polysomes, resulting in stalled 48S mRNPs which recruit available cytoplasmic RNA-binding proteins (blue region), many of which would normally shuttle into the nucleus (pink area). Locally high concentrations of mRNPs promote aggregation into small complexes, which progressively fuse into larger aggregates, assisted by microtubule-dependent motors. Sorting ensues as the higher affinity interactions prevail, and as other signaling molecules are recruited. Subsets of mRNPs may be removed from the SGs pending phosphorylation and 14-3-3 binding and shunted to PBs for decay (e.g., TTP). Other mRNPs may be exported for other fates.

SG initiation requires sudden polysome disassembly caused by stalled or abortive initiation. Metabolic labeling experiments indicate that translation must be severely affected (>90%) before SGs form in response to arsenite38 (Fig. 1A). Primary nucleation occurs when the stalled 48S mRNPs, suddenly stripped of ribosomes, create localized regions in which the free mRNA concentration suddenly spikes, favoring the binding of all locally available RNA-binding proteins, regardless of sequence. Many of these proteins (Table I) normally shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, but are trapped by their affinity for the suddenly high concentrations of free mRNA in the cytoplasm. This binding in turn localizes the RNA-binding proteins, many of which (SG nucleators) self-aggregate. Small mRNP aggregates rapidly form in an energy-independent manner, evenly dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (primary aggregation). Within the small SG aggregates, competition and exchange occur, as high-affinity sequence-specific interactions exchange with low-affinity, sequence-independent ones.

As most mRNA transcripts bind multiple RNA-binding proteins, cross-linking between mRNPs (secondary aggregation) occurs just as readily as self-aggregation. In particular, the C-terminal domain of PABP is notoriously insoluble, and as PABP is present on most transcripts, it facilitates this stage. Moreover, knockdown of PABP severely impairs SG assembly, as does overexpression of a C-terminal truncation of PABP (Kedersha, Tisdale, and Anderson, unpublished data). Small ribosomal subunits likely contribute to the aggregation, as O-GlcNAc modification of ribosomal subunits appears necessary to promote SG assembly downstream of polysome disassembly, but has less effect on P-body assembly.39

In the second phase of SG assembly, small aggregates fuse to form larger aggregates (growth/fusion). This stage is facilitated by microtubules and motors,40, 41, 42 whose disruption prevents the fusion of small SGs into larger ones. A growing number of proteins that do not directly bind RNA are indirectly recruited via “piggyback” interactions—those between signaling proteins and more proximal, core SG proteins that are highly concentrated in small foci. Within the larger SGs as well as in the smaller ones, mRNP sorting and remodeling occur, as the most stable mRNPs form, containing partners of the highest mutual affinity. The protein component of each mRNP could then determine the fate of its transcript. Some mRNAs might be reinitiated (left branch, yellow), others detached from the eIF3/40S complex and transferred to the decapping and decay machinery within PBs (e.g., those bound to TTP, bottom, dark blue), while others packaged into more long-lived storage granules (right branch, light blue). SG disassembly occurs when translation returns to normal (or polysomes are artificially stabilized via drugs). Note that the “new normal” following stress likely contains a different spectrum of transcripts, and that lack of proteins required to achieve this new normal state (ZBP1, staufen) will prolong the time it takes for SGs to disperse.

This model accounts for the following observations: (1) SG assembly is diminished, but not completely abolished, by knockdown of any individual SG-nucleating protein. (2) The abundance of a particular nucleator and its mRNA targets is proportional to the effects of its loss on SG assembly rate or size. (3) Proteins recruited to SGs by piggyback interactions are blocked from SG recruitment if their particular target protein is blocked or missing. As many of these are signaling proteins (CCAR1, TRAF2, SRC3, RSK2), this could have important functional effects on cell survival or growth. (4) Individual SG nucleators can exit SGs along with their associated mRNAs, without disassembly of the SG. For example, TTP leaves SGs but not PBs upon phosphorylation and 14-3-3-binding,12 whereas phosphorylated hMEX3B leaves PBs but not SGs when bound to 14-3-3.43

VII. Functions and Consequences of SG/PB Assembly

A. Alternative Splicing

A large number of SG-associated proteins (DBPA, FASTK, FMRP/FXR1, hnRNPA1, HuR, MBNL1, MLN51, SAM68, TIA-1/TIAR) are nuclear shuttling proteins which regulate alternative splicing, a regulated process usually studied by overexpression/depletion experiments. Although direct data are lacking, rerouting of these shuttling proteins to SGs should result in the altered splicing of genes transcribed during periods when SGs are present. This has been proposed to occur with hnRNPA1, a SG-associated multifunctional protein that regulates splicing (as well as microRNA processing). Its recruitment to SGs is predicated on its nuclear export, prior to its cytoplasmic phosphorylation which allows its targeting to SGs in an RNA-binding-dependent manner.

B. Survival

Core components of SGs are stalled 48S preinitiation complexes. One approach to determine whether SG assembly is pro- or antisurvival is to eliminate a specific eIF2α kinase and determine whether its loss sensitizes or promotes resistance to its activating stress. For example, HRI kinase mediates arsenite-induced SG assembly,30, 39 and HRI knockout MEFs and U2OS cells in which HRI is depleted by siRNA fail to respond to phospho-eIF2α or assemble SGs in response to arsenite, but exhibit unimpaired SG assembly in response to other stresses. Both HRI knockout MEFs and mice are resistant to arsenite,30 linking SG assembly to apoptosis.

By sequestering specific proteins that regulate cell survival, SGs may influence different signaling pathways that determine whether a stressed cell repairs its damage and lives, or dies by apoptosis. Deletion studies have shown that some SG-associated proteins regulate “relative viability” as assessed by ATP levels following stress (hnRNPA1,44; MLN51,26), whereas other proteins regulate survival/apoptosis in a localization-specific manner (RACK1,45; RSK2,46). For example, RACK1 is a scaffold protein required for the activation of the MAPKKK. When RACK1 is sequestered at SGs, this stress kinase cascade is inactive and stress-induced survival is enhanced. Similarly, the recruitment of RSK2 to SGs and to the nucleus requires its binding to TIA-1, which affects both its ability to induce cyclin D1 and promote survival following arsenite stress.46

C. Signaling

An important factor in modeling SG/PB dynamics must account for the contribution of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins in SG assembly. As shown in Table I, most SG-associated proteins other than initiation factors are nuclear shuttling proteins, including many (G3BP, FXR1/FMRP, TIA-1/TIAR) whose overexpression nucleates SGs. Knockdown of any one of these proteins delays SG formation or reduces the size of SGs, but does not abolish SG formation altogether. This suggests that these shuttling proteins contribute to the size of SGs, but act downstream of polysome disassembly. The relocalization of these normally nuclear proteins into cytoplasmic SGs must prevent their nuclear function(s) such as alternative splicing, transcription, mRNA processing, etc., thus allowing a mechanism whereby SG assembly can alter nuclear events. One nucleolar protein (SGNP) has been shown to accumulate in SGs, suggesting a link between SGs and ribosome assembly.

After acting as a nuclear transcriptional coactivator of NFκB-induced inflammatory cytokine genes, SRC-3 (steroid receptor co-activator-3) moves to the cytoplasm where it binds TIA-1 and promotes the translational silencing of TNFα mRNA. This enables it to turn off expression of the same genes that it turns on early in the inflammatory process.47 It requires binding to TIA-1 for its localization into SGs, and provides a clear molecular link between nuclear transcription and cytoplasmic translational silencing. Whether it also interacts with the TIA proteins to regulate cytokine splicing remains to be determined. In addition to SRC-3, the transcriptional coactivator CCAR1 (Cell division Cycle and Apoptosis Regulator 1) is recruited to SGs via interactions with G3BP/caprin1; the functional implications of CCAR1 at SGs remain to be determined.48

SG assembly is linked to membrane-associated signaling events as well as nuclear ones. TRAF2, a cytoplasmic signaling molecule that mediates TNFα signaling, is recruited to SGs upon heat shock, corresponding to its shift into an insoluble form due to its binding to eIF4G.49 Its sequestration in SGs prevents its association with the TNF receptor, suggesting a mechanism whereby fever-induced SGs could mute the immune response. Plakophilin-3 is recruited to SGs as part of a complex containing G3BP,49 linking SG formation with cell adhesion.

SG assembly is associated with a number of posttranslational modifications, among them phosphorylation, arginine methylation (CIRP),49 O-GlcNAc modification,39 ubiquitinylation (Tudor-3, HDAC6),41, 50, 51 and acetylation. It is also linked to the molecular chaperones HSP70 (which prevent aggregation of the prion-like domain of TIA-1) and HSP90, required for Ago-2 targeting to both SGs and PBs.52 Phosphorylation-driven binding to the chaperone 14-3-3 inhibits TTP interactions with SGs but not PBs, but is required for hMEX3B/Ago complexes to dock at PBs, yet has no effect on their targeting to SGs.

VIII. SG/PB Dynamics

Polysome disassembly is not sufficient to induce SGs or PBs: whereas puromycin promotes rapid (30 min) polysome disassembly, SG assembly is not observed for several hours.28 However, brief puromycin exposure lowers the threshold at which other SG/PB promoting drugs induce PB assembly,4 implicating the activation of pathways downstream of termination in the SG assembly process. A single species of mRNA can be assembled into a SG or a PB, even within the same cell.35 While the factors that influence sorting into distinct types of granules are not well understood, there is evidence that the mode of polysome disassembly affects the type of RNA granule that is assembled, leading to the following model. When polysome disassembly is initiated by deadenylation, depletion of PABP disrupts the link between the 5′- and 3′-ends of the transcript and allows the recruitment of decapping enzymes. These linearized transcripts recruit the decay machinery, and are thus assembled into PBs. When polysome disassembly is mediated by stalled initiation on a circularized mRNA, ribosome run-off leaves a circular mRNP that is assembled into SGs, thus accounting for the fact that eIF4E is present in both SGs and PBs, whereas only SGs contain eIF3, eIF4G, eIF4A, and PABP, while PBs contain instead the eIF4E binding protein 4-ET.

New information on SG/PB dynamics comes from an siRNA-based screen for genes that are required for SG/PB assembly in response to arsenite.39 Strikingly, five different subunits of eIF3 (eIF3c, d, e, g, and i) are required for SG but not PB assembly, while eIF3b is required for both SG and PB assembly. Notably, eIF3e mediates the interaction of eIF3 with eIF4G and stabilizes the circular form of the mRNA;53 its deletion would be predicted to destabilize circular mRNPs that might be preferentially routed to SGs rather than PBs. Not detected in the screen was eIF3j, a protein required for ribosome recycling54 suggesting that impairing recycling might prevent SG assembly. Moreover, eRF1 (eukaryotic translation release factor 1) was found to be required for PB, but not SG formation, also suggesting that the mode of polysome disassembly may influence whether SGs or PBs result.

IX. SGs and PBs in Disease

The importance of these RNA granules in the regulation of protein expression is underscored by their involvement in several aspects of disease pathogenesis. Our understanding of their roles in cellular physiology may allow us to exploit these regulatory pathways for the development of new classes of drugs for the treatment of disease.

A. Virus Infection

Studies of the translation of viral RNAs have provided general insights into mechanisms of protein translation. The finding that many viruses interact, functionally or physically, with SGs and PBs highlights their relevance to mRNA translation and decay. The different ways that viruses interact with RNA granules is summarized below.

Poliovirus is a plus-strand RNA virus that encodes proteinases that cleave essential host proteins to allow preferential transcription and translation of viral RNA. Poliovirus infection results in the transient assembly of SGs. The disassembly of SGs correlates with the cleavage of G3BP by viral proteinase 3C. Expression of a noncleavable G3BP mutant prevents the disassembly of SGs and inhibits virus production, suggesting that SGs function in host defense against virus infection.55, 56

Semliki Forest Virus is another plus-strand RNA virus that shuts down host protein synthesis prior to initiating the synthesis of virus proteins. This is accomplished, in part, by the activation of a stress response program that phosphorylates eIF2α to repress translation initiation. In MEFs expressing a nonphosphorylatable eIF2α mutant, host protein shutoff is markedly impaired. Phosphorylation of eIF2α results in the assembly of SGs during the early stages of virus infection, but SGs are disassembled as viral protein synthesis is initiated, and thereafter SGs cannot be induced by arsenite. Infection of TIA-1−/− MEFs that exhibit impaired SG assembly results in a significant delay in host protein synthesis shutoff. Thus, TIA-1 and SGs appear to facilitate host protein synthesis shutoff, and their disassembly is required for efficient translation of viral proteins.57

Reovirus is a double-stranded RNA virus that also activates a stress response program in infected cells. This involves the activation of PKR, phosphorylation of eIF2α, and transcription of ATF4. Individual strains of reovirus differ in the extent to which host protein synthesis is turned off following infection. The phospho-eIF2α induced assembly of SGs parallels the extent of host protein shut off in different reovirus strains. Thus, reovirus appears to utilize SGs to promote the preferential translation of virus proteins.58, 59

West Nile Virus is a plus-strand RNA virus that also induces host protein shut down in infected cells. TIA-1 and TIAR, related proteins that nucleate SG assembly, bind to a 3′-terminal stem loop in the minus strand viral RNA. During virus infection, TIA-1 and TIAR are concentrated at perinuclear sites of viral replication, suggesting that these proteins play a role in virus replication. Consistent with this possibility, virus replication is severely impaired in TIAR−/− MEFs. The sequestration of TIA-1 and TIAR at sites of virus replication has been proposed to contribute to the impaired assembly of SGs and PBs observed in virally infected cells.59

Sendai virus is a minus strand RNA virus that induces the assembly of SGs during virus infection. SG assembly is regulated by a short RNA transcribed from the 3′-end of plus-strand viral RNAs. This RNA binds and sequesters TIAR to impair SG assembly. Sequestration of TIAR also inhibits virus-induced apoptosis, a phenomenon that may promote cell survival to allow optimal virus production.60

Rotavirus is a double-stranded RNA virus that also promotes the phosphorylation of eIF2α in infected cells. Unlike Sindbis virus, reovirus and West Nile virus-infected cells, phospho-eIF2α does not induce SG assembly in rotavirus-infected cells. Moreover, the growth of rotavirus is not impaired in fibroblasts expressing a nonphosphorylatable eIF2α mutant. It is possible that rotavirus encodes a factor that prevents phospho-eIF2α-mediated translational repression and/or the aggregation of untranslated mRNPs.

Mouse Hepatitis Coronavirus is a plus-strand RNA virus that induces the phosphorylation of eIF2α and shuts down host protein synthesis in infected cells. Virus infection also induces the assembly of SGs and PBs suggesting that RNA granules play a role in reprogramming mRNA translation/decay during viral infection.61

Brome Mosaic Virus (BMV) is a plus-strand RNA virus that replicates in yeast. The translation and replication of BMV RNAs is dependent upon the PB components Pat1p, Dhh1p, and Lsm1p-7p. Moreover, BMV RNAs are concentrated in PBs suggesting that PBs facilitate viral replication.62

Retroviruses and retrotransposons share the ability to reverse transcribe DNA copies for insertion into the genome. APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F are antiviral proteins that deaminate cytidines in retroviral or retrotransposon-encoded RNAs. Although both of these proteins are concentrated at SGs and PBs, the functional significance of this localization remains to be determined.63 Similarly, TSN (Tudor staphylococcal nuclease) is a RISC-associated nuclease64 that specifically cleaves inosine-modified dsRNA, and associates with SGs.65 LINE-1 transposon, still active in the human genome, encodes LINE1p, a protein required for tranposition that nucleates SGs66and coaggregates the LINE-1 mRNA,67 suggesting that SG formation may be a manifestation of the host antiviral response.

B. Fragile X Syndrome (FXS)

Mutations in the fragile mental retardation protein (FMRP) are associated with an X-linked form of mental retardation. FMRP is an RNA-binding protein that is expressed in dendrites and at synapses. It has been proposed to function as a translational repressor that dampens the expression of synaptic proteins to impair neuronal function.68 In normal cells, FMRP is found in association with polysomes suggesting a possible role in protein translation. In cells subjected to oxidative stress, or in hippocampal neurons perturbed by electrode insertion, FMRP accompanies untranslated mRNAs to SGs.69 In cells lacking FMRP or expressing an FMRP mutant associated with FXS, SG assembly is markedly impaired70 suggesting that FMRP actively contributes to SG assembly. Impaired SG assembly may prevent the reprogramming of protein translation that is required to protect cells from the adverse effects of environmental stress. It is possible that mental retardation in FXS resulting from neuronal cell death is caused by impaired SG assembly.

C. Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Disease

SG assembly has been shown to regulate several aspects of immune cell function and inflammation. SGs are assembled following T cell receptor-mediated activation of CD4+ T cells. In these cells, IL-4 and IL-13 mRNAs are transcribed and held in a translationally repressed state. T cell receptor-mediated restimulation releases these transcripts from translational repression allowing cytokine secretion. Lentiviral expression of a dominant-negative mutant of the SG nucleator TIA-1 releases the activation-induced translational silencing of these transcripts, implicating SGs in the regulation of T cell activation.71

Roquin is an E3 ligase that regulates the expression of ICOS, a costimulatory molecule that promotes T cell activation.72 Mutant mice expressing mutant roquin overexpress ICOS and develop a severe autoinflammatory disease. Roquin appears to promote the miRNA-dependent repression of ICOS expression. As roquin resides at SGs and PBs, these RNA granules may be involved in this autoimmune syndrome.

SG and PB partitioning may also regulate the expression of inflammatory proteins in activated macrophages. TTP, an mRNA destabilizing protein that represses the expression of inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNFα, IL-1b, IL-6), plays a major role in regulating interactions between SGs and PBs.35 In activated macrophages, TTP is phosphorylated and complexed with 14-3-3 proteins, modifications that prevent it from delivering its associated mRNAs to the degradation machinery.73 Because phosphorylation of TTP causes SG:PB conjugates to dissociate, inhibition of mRNA decay may be a consequence of altered SG:PB interactions.

D. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

Reduced blood flow caused by transient occlusion of the carotid artery or by reduced cardiac output confers ischemic injury to susceptible neurons. Resumption of blood flow after ischemia can potentiate this process by a number of different mechanisms. In postischemic neurons, protein translation is turned off to conserve anabolic energy for the repair of stress-induced damage. In neurons that are particularly susceptible to ischemic injury (e.g., hippocampal cornu ammonis 1; CA1), translational arrest is prolonged and translational reprogramming that allows the preferential translation of repair proteins (e.g., heat-shock proteins) is impaired. In neurons that are relatively resistant to ischemia, SGs are transiently assembled. In CA1 neurons, SGs persist for prolonged periods. The persistence of SGs correlates with the prolonged translational arrest observed in these cells.74 In addition to SGs, a related RNA granule characterized by the presence of HuR and the absence of TIA-1 is observed in ischemic CA1 neurons. Besides exhibiting prolonged translational arrest, these cells fail to synthesize protective heat-shock proteins in response to ischemic insults.75 Thus, alterations in the assembly and function of different types of RNA granules may impair translational reprogramming in the susceptible CA1 neuron leading to increased vulnerability to ischemic injury.

X. Conclusions

SG and PB formation is a regulated consequence of translational arrest, but there appears to be many levels to the story. Monitoring SG formation may be of diagnostic use in assessing viral infection or hypoxia, as it affords us a window on the translational status of individual cells within tissues. However, while SGs and PBs are primarily sites of remodeling, packaging, and sorting of mRNA, their assembly is linked to other cellular processes and pathways via a growing number of specific proteins. SGs secondarily recruit proteins involved in splicing, transcription, and signaling as part of an adaptive process. Defining the specific molecules that link SG formation to other pathways, and selectively targeting them may be of therapeutic value. The impact of PB/GWB formation on other pathways is presently less clear, but the ongoing river of data will doubtlessly flush out new ideas as these exciting young fields mature.

References

- 1.Kedersha N.L., Gupta M., Li W., Miller I., Anderson P. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2α to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1431–1441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nover L., Scharf K.D., Neumann D. Cytoplasmic heat shock granules are formed from precursor particles and are associated with a specific set of mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1298–1308. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber C., Nover L., Fauth M. Plant stress granules and mRNA processing bodies are distinct from heat stress granules. Plant J. 2008;56:517–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kedersha N., Cho M., Li W., Yacono P., Chen S., Golan D. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 2000. Mammalian stress granules: highly dynamic sites of mRNA triage during stress induced translational arrest. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piecyk M., Wax S., Beck A.R., Kedersha N., Gupta M., Maritim B. TIA-1 is a translational silencer that selectively regulates the expression of TNF-alpha. EMBO J. 2000;19:4154–4163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson P., Kedersha N. Visibly stressed: the role of eIF2, TIA-1, and stress granules in protein translation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2002;7:213–221. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0213:vstroe>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson P., Kedersha N. Stressful initiations. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3227–3234. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.16.3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kedersha N., Chen S., Gilks N., Li W., Miller I.J., Stahl J. Evidence that ternary complex (eIF2-GTP-tRNA(i)(Met))-deficient preinitiation complexes are core constituents of mammalian stress granules. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:195–210. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimball S.R., Horetsky R.L., Ron D., Jefferson L.S., Harding H.P. Mammalian stress granules represent sites of accumulation of stalled translation initiation complexes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C273–C284. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00314.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tourriere H., Chebli K., Zekri L., Courselaud B., Blanchard J.M., Bertrand E. The RasGAP-associated endoribonuclease G3BP assembles stress granules. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:823–831. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Irvine K., Stirling R., Hume D., Kennedy D. Rasputin, more promiscuous than ever: a review of G3BP. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1065–1077. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041893ki. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoecklin G., Stubbs T., Kedersha N., Wax S., Rigby W.F., Blackwell T.K. MK2-induced tristetraprolin: 14-3-3 complexes prevent stress granule association and ARE-mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2004;23:1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low W.K., Dang Y., Schneider-Poetsch T., Shi Z., Choi N.S., Merrick W.C. Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation by the marine natural product pateamine A. Mol Cell. 2005;20:709–722. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordeleau M.E., Cencic R., Lindqvist L., Oberer M., Northcote P., Wagner G. RNA-mediated sequestration of the RNA helicase eIF4A by pateamine A inhibits translation initiation. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dang Y., Kedersha N., Low W.K., Romo D., Gorospe M., Kaufman R. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha-independent pathway of stress granule induction by the natural product pateamine A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32870–32878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazroui R., Sukarieh R., Bordeleau M.E., Kaufman R.J., Northcote P., Tanaka J. Inhibition of ribosome recruitment induces stress granule formation independently of eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4212–4219. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadler A.J., Latchoumanin O., Hawkes D., Mak J., Williams B.R. An antiviral response directed by PKR phosphorylation of the RNA helicase A. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000311. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth U., Parker R. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2003;300:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1082320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cougot N., Babajko S., Seraphin B. Cytoplasmic foci are sites of mRNA decay in human cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:31–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eulalio A., Behm-Ansmant I., Izaurralde E. P bodies: at the crossroads of post-transcriptional pathways. Nat Rev. 2007;8:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker R., Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garneau N.L., Wilusz J., Wilusz C.J. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat Rev. 2007;8:113–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franks T., Lykke-Andersen J. The control of mRNA decapping and P-body formation. Mol Cell. 2008;32:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding H.P., Zhang Y., Bertolotti A., Zeng H., Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams B.R. Signal integration via PKR. Sci STKE. 2001;2001 doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.89.re2. RE2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baguet A., Degot S., Cougot N., Bertrand E., Chenard M.P., Wendling C. The exon-junction-complex-component metastatic lymph node 51 functions in stress-granule assembly. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2774–2784. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubtsova M.P., Sizova D.V., Dmitriev S.E., Ivanov D.S., Prassolov V.S., Shatsky I.N. Distinctive properties of the 5′-untranslated region of human hsp70 mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22350–22356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kedersha N., Anderson P. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 2007;431:61–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheuner D., Song B., McEwen E., Liu C., Laybutt R., Gillespie P. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farny N.G., Kedersha N.L., Silver P.A. Metazoan stress granule assembly is mediated by P-eIF2{alpha}-dependent and -independent mechanisms. RNA. 2009 doi: 10.1261/rna.1684009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEwen E., Kedersha N., Song B., Scheuner D., Gilks N., Han A. Heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) kinase-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2) inhibits translation, induces stress granule formation, and mediates survival upon arsenite exposure. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16925–16933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoyle N.P., Castelli L.M., Campbell S.G., Holmes L.E., Ashe M.P. Stress-dependent relocalization of translationally primed mRNPs to cytoplasmic granules that are kinetically and spatially distinct from P-bodies. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:65–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brengues M., Parker R. Accumulation of polyadenylated mRNA, Pab1p, eIF4E, and eIF4G with P-bodies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2592–2602. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchan J.R., Muhlrad D., Parker R. P bodies promote stress granule assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:441–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grousl T., Ivanov P., Frydlova I., Vasicova P., Janda F., Vojtova J. Robust heat shock induces eIF2{alpha}-phosphorylation-independent assembly of stress granules containing eIF3 and 40S ribosomal subunits in budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2078–2088. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kedersha N., Stoecklin G., Ayodele M., Yacono P., Lykke-Andersen J., Fritzler M.J. Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:871–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Handwerger K.E., Gall J.G. Subnuclear organelles: new insights into form and function. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilczynska A., Aigueperse C., Kress M., Dautry F., Weil D. The translational regulator CPEB1 provides a link between dcp1 bodies and stress granules. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:981–992. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kedersha N., Cho M.R., Li W., Yacono P.W., Chen S., Gilks N. Dynamic shuttling of TIA-1 accompanies the recruitment of mRNA to mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1257–1268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohn T., Kedersha N., Hickman T., Tisdale S., Anderson P. A functional RNAi screen links O-GlcNAc modification of ribosomal proteins to stress granule and processing body assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1224–1231. doi: 10.1038/ncb1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai N.P., Tsui Y.C., Wei L.N. Dynein motor contributes to stress granule dynamics in primary neurons. Neuroscience. 2009;159:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon S., Zhang Y., Matthias P. The deacetylase HDAC6 is a novel critical component of stress granules involved in the stress response. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3381–3394. doi: 10.1101/gad.461107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivanov P.A., Chudinova E.M., Nadezhdina E.S. Disruption of microtubules inhibits cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein stress granule formation. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290:227–233. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Courchet J., Buchet-Poyau K., Potemski A., Bres A., Jariel-Encontre I., Billaud M. Interaction with 14-3-3 adaptors regulates the sorting of hMex-3B RNA-binding protein to distinct classes of RNA granules. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32131–32142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guil S., Long J.C., Caceres J.F. hnRNP A1 relocalization to the stress granules reflects a role in the stress response. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5744–5758. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00224-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arimoto K., Fukuda H., Imajoh-Ohmi S., Saito H., Takekawa M. Formation of stress granules inhibits apoptosis by suppressing stress-responsive MAPK pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/ncb1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisinger-Mathason T.S., Andrade J., Groehler A.L., Clark D.E., Muratore-Schroeder T.L., Pasic L. Codependent functions of RSK2 and the apoptosis-promoting factor TIA-1 in stress granule assembly and cell survival. Mol Cell. 2008;31:722–736. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu C., York B., Wang S., Feng Q., Xu J., O'Malley B.W. An essential function of the SRC-3 coactivator in suppression of cytokine mRNA translation and inflammatory response. Mol Cell. 2007;25:765–778. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolobova E., Efimov A., Kaverina I., Rishi A.K., Schrader J.W., Ham A.J. Microtubule-dependent association of AKAP350A and CCAR1 with RNA stress granules. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:542–555. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim W.J., Back S.H., Kim V., Ryu I., Jang S.K. Sequestration of TRAF2 into stress granules interrupts tumor necrosis factor signaling under stress conditions. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2450–2462. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2450-2462.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linder B., Plottner O., Kroiss M., Hartmann E., Laggerbauer B., Meister G. Tdrd3 is a novel stress granule-associated protein interacting with the Fragile-X syndrome protein FMRP. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3236–3246. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goulet I., Boisvenue S., Mokas S., Mazroui R., Cote J. TDRD3, a novel tudor domain-containing protein, localizes to cytoplasmic stress granules. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3055–3074. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pare J.M., Tahbaz N., Lopez-Orozco J., LaPointe P., Lasko P., Hobman T.C. Hsp90 regulates the function of argonaute 2 and its recruitment to stress granules and P-bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3273–3284. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-01-0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LeFebvre A.K., Korneeva N.L., Trutschl M., Cvek U., Duzan R.D., Bradley C.A. Translation initiation factor eIF4G-1 binds to eIF3 through the eIF3e subunit. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22917–22932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605418200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pisarev A.V., Hellen C.U., Pestova T.V. Recycling of eukaryotic posttermination ribosomal complexes. Cell. 2007;131:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.White J.P., Cardenas A.M., Marissen W.E., Lloyd R.E. Inhibition of cytoplasmic mRNA stress granule formation by a viral proteinase. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schutz S., Sarnow P. How viruses avoid stress. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:284–285. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McInerney G.M., Kedersha N.L., Kaufman R.J., Anderson P., Liljestrom P. Importance of eIF2alpha phosphorylation and stress granule assembly in alphavirus translation regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3753–3763. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith J.A., Schmechel S.C., Raghavan A., Abelson M., Reilly C., Katze M.G. Reovirus induces and benefits from an integrated cellular stress response. J Virol. 2006;80:2019–2033. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.2019-2033.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emara M.M., Brinton M.A. Interaction of TIA-1/TIAR with West Nile and dengue virus products in infected cells interferes with stress granule formation and processing body assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9041–9046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703348104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iseni F., Garcin D., Nishio M., Kedersha N., Anderson P., Kolakofsky D. Sendai virus trailer RNA binds TIAR, a cellular protein involved in virus-induced apoptosis. EMBO J. 2002;21:5141–5150. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raaben M., Groot Koerkamp M.J., Rottier P.J., de Haan C.A. Mouse hepatitis coronavirus replication induces host translational shutoff and mRNA decay, with concomitant formation of stress granules and processing bodies. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2218–2229. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beckham C.J., Light H.R., Nissan T.A., Ahlquist P., Parker R., Noueiry A. Interactions between brome mosaic virus RNAs and cytoplasmic processing bodies. J Virol. 2007;81:9759–9768. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00844-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gallois-Montbrun S., Kramer B., Swanson C.M., Byers H., Lynham S., Ward M. Antiviral protein APOBEC3G localizes to ribonucleoprotein complexes found in P bodies and stress granules. J Virol. 2007;81:2165–2178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02287-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caudy A.A., Ketting R.F., Hammond S.M., Denli A.M., Bathoorn A.M., Tops B.B. A micrococcal nuclease homologue in RNAi effector complexes. Nature. 2003;425:411–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scadden A.D. Inosine-containing dsRNA binds a stress-granule-like complex and downregulates gene expression in trans. Mol cell. 2007;28:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodier J.L., Zhang L., Vetter M.R., Kazazian H.H., Jr LINE-1 ORF1 protein localizes in stress granules with other RNA-binding proteins, including components of RNAi RISC. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6469–6483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00332-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goodier J.L., Kazazian H.H., Jr. Retrotransposons revisited: the restraint and rehabilitation of parasites. Cell. 2008;135:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bassell G.J., Warren S.T. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim S.H., Dong W.K., Weiler I.J., Greenough W.T. Fragile X mental retardation protein shifts between polyribosomes and stress granules after neuronal injury by arsenite stress or in vivo hippocampal electrode insertion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2413–2418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3680-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Didiot M.C., Subramanian M., Flatter E., Mandel J.L., Moine H. Cells lacking the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) have normal RISC activity but exhibit altered stress granule assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:428–437. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scheu S., Stetson D.B., Reinhardt R.L., Leber J.H., Mohrs M., Locksley R.M. Activation of the integrated stress response during T helper cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:644–651. doi: 10.1038/ni1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vinuesa C.G., Cook M.C., Angelucci C., Athanasopoulos V., Rui L., Hill K.M. A RING-type ubiquitin ligase family member required to repress follicular helper T cells and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nature03555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stoecklin G., Stubbs T., Kedersha N., Blackwell T.K., Anderson P. MK2-induced tristetraprolin:14-3-3 complexes prevent stress granule association and ARE-mRNA decay. EMBO J. 2004;23:1313–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kayali F., Montie H.L., Rafols J.A., DeGracia D.J. Prolonged translation arrest in reperfused hippocampal cornu Ammonis 1 is mediated by stress granules. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1223–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jamison J.T., Kayali F., Rudolph J., Marshall M., Kimball S.R., DeGracia D.J. Persistent redistribution of poly-adenylated mRNAs correlates with translation arrest and cell death following global brain ischemia and reperfusion. Neuroscience. 2008;154:504–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sen G.L., Blau H.M. Argonaute 2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:633–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leung A.K., Calabrese J.M., Sharp P.A. Quantitative analysis of Argonaute protein reveals microRNA-dependent localization to stress granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18125–18130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608845103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kozak S.L., Marin M., Rose K.M., Bystrom C., Kabat D. The anti-HIV-1 editing enzyme APOBEC3G binds HIV-1 RNA and messenger RNAs that shuttle between polysomes and stress granules. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29105–29119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wichroski M.J., Robb G.B., Rana T.M. Human retroviral host restriction factors APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F localize to mRNA processing bodies. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nonhoff U., Ralser M., Welzel F., Piccini I., Balzereit D., Yaspo M.L. Ataxin-2 interacts with the DEAD/H-box RNA helicase DDX6 and interferes with P-bodies and stress granules. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1385–1396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Decca M.B., Carpio M.A., Bosc C., Galiano M.R., Job D., Andrieux A. Post-translational arginylation of calreticulin: a new isospecies of calreticulin component of stress granules. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8237–8245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608559200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solomon S., Xu Y., Wang B., David M.D., Schubert P., Kennedy D. Distinct structural features of caprin-1 mediate its interaction with G3BP-1 and its induction of phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2alpha, entry to cytoplasmic stress granules, and selective interaction with a subset of mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2324–2342. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02300-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rothe F., Gueydan C., Bellefroid E., Huez G., Kruys V. Identification of FUSE-binding proteins as interacting partners of TIA proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Leeuw F., Zhang T., Wauquier C., Huez G., Kruys V., Gueydan C. The cold-inducible RNA-binding protein migrates from the nucleus to cytoplasmic stress granules by a methylation-dependent mechanism and acts as a translational repressor. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:4130–4144. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nousch M., Reed V., Bryson-Richardson R.J., Currie P.D., Preiss T. The eIF4G-homolog p97 can activate translation independent of caspase cleavage. RNA (New York, N.Y.) 2007;13:374–384. doi: 10.1261/rna.372307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Onishi H., Kino Y., Morita T., Futai E., Sasagawa N., Ishiura S. MBNL1 associates with YB-1 in cytoplasmic stress granules. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1994–2002. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lai M.C., Lee Y.H., Tarn W.Y. The DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX3 associates with export messenger ribonucleoproteins as well as tip-associated protein and participates in translational control. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3847–3858. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chalupnikova K., Lattmann S., Selak N., Iwamoto F., Fujiki Y., Nagamine Y. Recruitment of the RNA helicase RHAU to stress granules via a unique RNA-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35186–35198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804857200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ogawa F., Kasai M., Akiyama T. A functional link between Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schwartz D., Decker C.J., Parker R. The enhancer of decapping proteins, Edc1p and Edc2p, bind RNA and stimulate the activity of the decapping enzyme. RNA (New York, N.Y.) 2003;9:239–251. doi: 10.1261/rna.2171203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fenger-Gron M., Fillman C., Norrild B., Lykke-Andersen J. Multiple processing body factors and the ARE binding protein TTP activate mRNA decapping. Mol Cell. 2005;20:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferraiuolo M.A., Basak S., Dostie J., Murray E.L., Schoenberg D.R., Sonenberg N. A role for the eIF4E-binding protein 4E-T in P-body formation and mRNA decay. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:913–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]