Summary

Mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) is a clinico-radiological syndrome that can be related to infectious and non-infectious conditions. Patients present with mild neurological symptoms, and magnetic resonance imaging typically demonstrate a reversible lesion with transiently reduced diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum. Here, we describe MERS in a 10-year-old boy who presented with fever and consciousness and who completely recovered within a few days. Streptococcus pneumoniae was the causative agent. Although viruses (especially influenza A and B) are the most common pathogen of MERS, for proper management, bacteria should be considered, as they may also lead to this condition.

Keywords: Mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion (MERS), MRI, Splenium of the corpus callosum, Child

Introduction

Mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) is a clinico-radiological syndrome that is characterized by a prodromal illness (fever, cough, vomiting or diarrhea), followed 1–7 days later by encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesions with high-signal-intensity on T2-weighted images and transiently reduced diffusion in the corpus callosum [1]. Sometimes, this illness is associated with symmetrical white matter lesions. These changes disappear completely or nearly completely on follow-up imaging within days to weeks [2]. The most common neurological symptoms are behavioral changes, altered consciousness, and seizures [3]. Most patients with MERS clinically recover within 1 month [4]. The major causative agents of MERS are viruses, especially influenza types A and B [4]. Bacterial infection-related MERS has also been reported in a few patients. Here, we report a 10-year-old patient with MERS due to Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia.

Case report

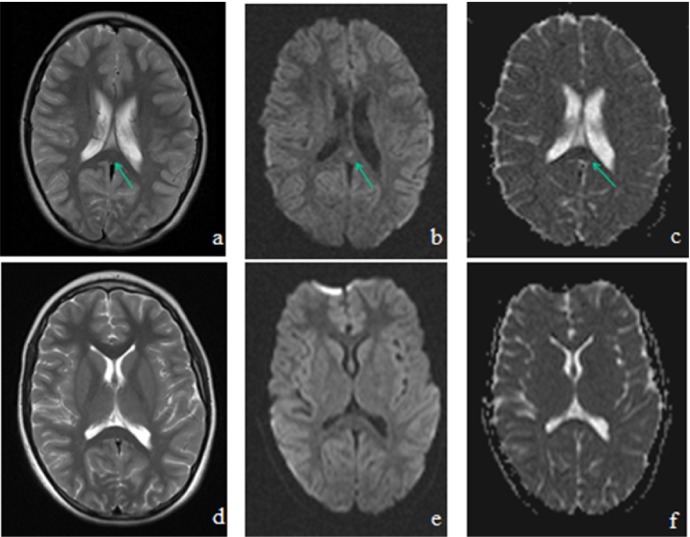

A 10-year-old boy was admitted with a history of fever and vomiting for a few days. He had been treated for rhinosinusitis. His family history was unremarkable. He was disoriented and was taken to the pediatric intensive care unit with a significantly low Glasgow coma score [GCS: 10 (E3V3M4); eye opening, 4; verbal response, 4; motor response, 5]. On clinical examination, he was lethargic, and he had a fever (39 °C) and spontaneous oral-buccal movements (chewing, swallowing), suggestive of motor automatismswere noticed. There were no focal neurologic signs, and meningeal irritation signs were also negative. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell; 23.000/mm3) and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 11.2 mg/dL. Biochemical parameters were normal except hyponatremia was noted (Na: 128 mEq/L). On the first day of admission, he had hypertension (170/100 mmHg) and GCS worsened. Cranial computed tomography (CT) was consistent with pansinusitis. Cefotaxime, vancomycin and acyclovir treatment were started for suspected central nervous system (CNS) infection, and phenytoin was added for seizures. Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) was clear in appearance, and the pressure was normal. Laboratory examination of CSF revealed pleocytosis (300/mm3 with neutrophil predominance), an elevated protein level of 194 mg/dL and a normal glucose level. Electroencephalography (EEG) was normal and showed no seizure-related activity. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of a nasopharyngeal specimen (influenza, parainfluenza, rhinovirus, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, bocavirus, and coronavirus) and CSF (herpes simplex virus, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HHV-6, and influenza) were negative. An autoimmune encephalitis panel (NMDA, CASPR2, LGI1, anti-Hu, anti-Yo, anti-Ma2) was also negative. Blood serology tests for EBV, CMV, HSV, Parvovirus, measles, mumps, rubella, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Borellia burgdorferi, and brucellosis remained negative. T2-weighted and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging showed an intensified signal in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 1 ). Bacteriologic culture of CSF was negative, but blood culture was positive for S. pneumoniae (penicillin-sensitive). After S. pneumoniae infection was confirmed, acyclovir and vancomycin were discontinued, and cefotaxime (200 mg/kg/day) was administered for 10 days. The patient completely recovered without any sequelae and was discharged on the 10th day of hospitalization. Follow-up MRI 15 days after the first imaging demonstrated a complete disappearance of the abnormal signal in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cranial MRI showing focal high intensity signal in the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC) on T2-weighted images (A), diffusion-weighted images (B) and hypointensity on an apparent diffusion coefficient map (C) at the time of admission (arrow), with a complete resolution of the SCC lesions on T2-weighted images (D), diffusion weighted images (E) and an apparent diffusion coefficient map (F) on day 15 after administration of appropriate therapy.

Discussion

A reversible isolated lesion with transiently reduced diffusion in the splenium of the corpus callosum has become a better-recognized entity recently with MRI studies. This situation is referred to as reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES), which can be observed in many different conditions and diseases [5]. The most common cause of RESLES in children is MERS; however, it can be associated with various other conditions, including acute or subacute encephalitis/encephalopathy, antiepileptic drug toxicity or withdrawal, and metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, hypernatremia), in addition to MERS in adults.

We describe a 10-year-old boy who presented with disturbances in consciousness and motor automatisms. His altered consciousness disappeared and GCS improved (E4V5M6), and within 24 h, the splenial lesion with high-signal-intensity on T2-weighted MRI began to resolve and was completely resolved within two weeks. There was no history of antiepileptic drug use, and he did not have epilepsy or a serious metabolic disorder. Meningitis was not considered because there was no evidence of meningeal irritation (neck stiffness, Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs) on physical examination, pleocytosis was not significant (leukocyte count in CSF was lower than expected), the CSF glucose level was within normal limits, and finally, the CSF culture was negative. Aseptic meningitis may be considered, but seizure-like movements and a significantly lower GCS were more suggestive of encephalitis. Mild encephalitis was more likely than encephalopathy due to the presence of fever and pleocytosis.

MERS is characterized by mild neurological symptoms with complete clinical recovery. Delirious behavior is observed in 54% of patients, consciousness disturbances are observed in 35% and seizures are observed in 33% [6]. This patient’s clinical and radiological findings were similar to those of previously reported MERS patients except that his condition was associated with a febrile infection due to S. pneuminae. The major pathogens of MERS are influenza virus (A and B), mumps virus, adenovirus and rotavirus. Bacterial pathogens are known to cause MERS, but they are rarely reported and constitute 3.3% of all causes of MERS [7]. Streptococci, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have been reported as bacterial pathogens of MERS [8], [1]. In 41% of patients, the causative pathogen remained unknown in the largest series in the literature [1]. Noninfectious conditions, such as Kawasaki disease and antiepileptic drugs, have also been described [9].

Several mechanisms have been proposed for the pathogenesis of MERS. Reduced diffusion in the splenium has been explained by intramyelinic or interstitial edema, which can be potentiated by hyponatremia. Takanashi et al. [10] reported that most patients with MERS had mild hyponatremia (131.0 ± 4.1 mmol/L), but it is difficult to determine whether this hyponatremia is the real cause of the illness. Similarly, the patient in this case had hyponatremia, but S. pneumoniae was considered to be the causative agent because of the patient’s fever, respiratory infection findings and positive blood culture. Axonal damage, oxidative stress and activation of the immune system are considered to be associated with pathogenesis of MERS [4]. Additionally, local infiltration by inflammatory cells could lead to reduced diffusion on MRI. Similar to our case, pleocytosis, a sign of inflammation in the central nervous system, is reported in patients with MERS [4]. Genetic factors may also play a role because patients with MERS have been most commonly seen in Southeast Asia. Although several mechanisms have been proposed for MERS, and the exact pathophysiology is still uncertain.

Methylprednisolone pulse therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin are recommended for patients with infectious encephalopathy to suppress the inflammatory cytokines, regardless of the pathogen or the clinico-radiological syndromes [11]. However, the efficacy of these medications is not clear in MERS. Patients with MERS who recovered completely without such treatments are reported in the literature, suggesting that steroids and intravenous immunoglobulin are not always necessary. The consciousness of our patient improved within 24 h; he did not receive the recommended treatment models, but more clinical experience is needed to believe that MERS does not require specific treatment.

In conclusion, we present a patient with encephalitis and a reversible splenial lesion due to S. pneumoniae. The patient’s disturbance in consciousness recovered quickly, and the splenial lesion completely disappeared, similar to other cases with MERS. Bacterial pathogens as well as viruses may cause MERS, and this fact should be kept in mind for patients with symptoms of aseptic meningitis (fever, headache, vomiting). MRI should be performed to evaluate the splenium of the corpus callosum and to avoid unnecessary tests and treatments.

Conflict of interest

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Gulhadiye Avcu, Email: gul_akbas@yahoo.com.tr.

Mehmet A. Kilinc, Email: makilinc@hotmail.com.

Cenk Eraslan, Email: eraslancenk@hotmail.com.

Bulent Karapinar, Email: bulent.karapinar@ege.edu.tr.

Fadil Vardar, Email: fadil.vardar@ege.edu.tr.

References

- 1.Takanashi J. Two newly proposed infectious encephalitis/encephalopathy syndromes. Brain Dev. 2009;31:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tada H., Takanashi J., Barkovich A., Oba H., Maeda M., Tsukahara H. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Neurology. 2004;63:1854–1858. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144274.12174.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abenhaim Halpern L., Agyeman P., Steinlin M., El-Koussy M., Grunt S. Mild encephalopathy with splenial lesion and parainfluenza virus infection. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;48:252–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto T., Sato Y., Yamazaki T., Hayashi A. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion associated with febrile urinary tract infection. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:533–536. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2199-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S., Ma Y., Feng J. Clinicoradiological spectrum of reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES) in adults. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:512–522. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takanashi J., Shiihara T., Hasegawa T., Takayanagi M., Hara M., Okumura A. Clinically mild encephalitis with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) after mumps vaccination. J Neurol Sci. 2015;349:226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino A., Saitoh M., Oka A., Okumura A., Kubota M., Saito Y. Epidemiology of acute encephalopathy in Japan, with emphasis on the association of viruses and syndromes. Brain Dev. 2012;34:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganapathy S., Ey E.H., Wolfson B.J., Khan N. Transient isolated lesion of the splenium associated with clinically mild influenza encephalitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:1243–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0949-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takanashi J., Shirai K., Sugawara Y., Okamoto Y., Obonai T., Terada H. Kawasaki disease complicated by mild encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) J Neurol Sci. 2012;315:167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takanashi J., Tada H., Maeda M., Suzuki M., Terada H., Barkovich A.J. Encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion is associated with hyponatremia. Brain Dev. 2009;31:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizuguchi M., Yamanouchi H., Ichiyama T., Shiomi M. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza and other viral infections. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;115:45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]