Abstract

According to spillover theory (Engfer, 1988), disruptions in one relationship (e.g., interparental) may lead to perturbations in another (e.g., parent–child) and these boundary disturbances have been linked to child psychopathology. Yet, few studies have explored spillover from both constructive and destructive interparental conflict in relation to children’s symptoms of psychopathology, and fewer have differentiated mothers’ and fathers’ parenting in these investigations. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to explore mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices—specifically, their inconsistent discipline, unsupportive reactions, and control through guilt—as indirect pathways between constructive and destructive interparental conflict and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Two sequential mediation models were constructed—one for destructive interparental conflict and another for constructive interparental conflict—using three waves of data collected annually beginning when children (N = 235) were approximately 6 years old. Direct effects of the two models showed that constructive conflict was associated with lower levels of problematic parenting practices, whereas destructive conflict was associated with higher levels. Indirect effects findings showed that mothers’ control through guilt was an explanatory mechanism between constructive and destructive interparental conflict and children’s externalizing symptoms, whereas mothers’ unsupportive reactions were a significant intermediary process between constructive interparental conflict and children’s internalizing symptoms. Therefore, results of the current study support the spillover hypothesis and suggest that differentiating mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices—as well as distinguishing between constructive and destructive interparental conflict—remain important, as each can have distinct relations to child adjustment.

Keywords: internalizing, externalizing, interparental conflict, parenting

All households experience interparental conflict to some degree (Kaczynski, Lindahl, Malik, & Laurenceau, 2006); however, not all forms of conflict hold the same implications for children’s development. Destructive interparental conflict—including behaviors like verbal or physical aggression, stonewalling, or hostility—has been linked to a host of negative outcomes for children, including their internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Cummings & Davies, 2010). Moreover, studies have shown that destructive conflict may impede effective parenting efforts (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Erel & Burman, 1995; Kaczynski et al., 2006) and deteriorating parental functioning has emerged as an important mediator between interparental conflict and child adjustment (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Coln, Jordan, & Mercer, 2013; Kaczynski et al., 2006). However, the direct and indirect pathways of these interactions to children’s symptoms of psychopathology warrant further attention, as few studies have included both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and fewer have investigated constructive conflict.

Spillover from the Interparental Dyad to the Parent–Child Relationship

Family relationships are interdependent and the spillover hypothesis (Engfer, 1988) suggests that disruptions in one relationship (e.g., interparental) may lead to perturbations in another (e.g., parent–child). Because interparental conflict can preoccupy parents and be emotionally draining (Coln et al., 2013), parents’ affect or behavior from their disagreements with their partners may “spill over” to other family subsystems (Buehler, Benson, & Gerard, 2006; Buehler & Gerard, 2002). When these interactions are destructive, it may become difficult for parents to remain emotionally available and sensitive to their children’s needs, leading some parents to engage in problematic parenting practices (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Coln et al., 2013; Cui & Conger, 2008; Gonzales, Pitts, Hill, & Roosa, 2000; Kaczynski et al, 2006). Multiple studies (e.g., Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Coln et al., 2013; Cui & Conger, 2008) and meta-analyses (e.g., Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000) of destructive conflict and problematic parenting have supported the spillover hypothesis and suggest that this spillover may predict child maladjustment longitudinally (Coln et al., 2013). Cummings and Davies (2010) have posited a theoretical role of emotional security processes (e.g., children’s anxiety about parents as sources of protection; increased adults’ relationship insecurity) as an explanatory model for these boundary intrusions (Davies, Sturge-Apple, Woitach, & Cummings, 2009).

Researchers have explored children’s maladjustment in relation to several problematic parenting practices, including inconsistent discipline, unsupportive reactions to children’s negative emotions, and control through guilt. Evidence suggests that parents involved in interparental conflict may discipline their children differently depending on the status of their marital relationship and this inconsistency may stem from the taxing nature of destructive conflicts (Kaczynski et al., 2006). Inconsistent discipline occurs when one or both parents frequently alter their disciplinary tactics from one situation to the next, or they enforce rules differently or utilize different disciplinary strategies than one another (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). After destructive arguments, parents may lack the energy to interact effectively with their children (Kaczynski et al., 2006), leading to inconsistent and ineffective discipline and, subsequently, children’s antisocial behavior (Fauber, Forehand, Thomas, & Wierson, 1990).

Interparental conflict may spill over in other ways as well. When children display negative emotions, parents may respond with supportive reactions—like validating the child’s negative emotions, comforting them, and helping them solve the problem—or unsupportive reactions—such as punishing the child, devaluing the child’s problem, or parents becoming distressed themselves (Fabes, Eisenberg, & Bernzweig, 1990). Strong associations have been found between interparental conflict and unsupportive reactions like harsh punishment or lack of acceptance of the child (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000) and ample evidence associates these parenting behaviors with above-average levels of externalizing and internalizing symptoms in children (Cui & Conger, 2008; Mann & MacKenzie, 1996).

Alternatively, parents facing high levels of destructive interparental conflict may blame their children for their marital difficulties and may try to overly control their children’s behavior through psychological control (Coln et al., 2013; Engfer, 1988). Psychological control is an emotionally manipulative practice in which parents may induce shame or guilt in their children to control their behavior (Coln et al., 2013). After destructive conflict, parents may use control through guilt to secure and maintain support from the child, coercing the child into an emotional alliance with the one parent (Fauber et al., 1990). Unsurprisingly then, control through guilt and other forms of psychological control have been shown to mediate the association between destructive conflict and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Buehler et al., 2006; Coln et al., 2013; Kaczynski et al., 2006). Taken together, these findings stress the deleterious impact of these problematic parenting practices.

Similarities and Differences in Mothers’ and Fathers’ Parenting

Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors may be becoming more similar as parents’ roles converge, with fathers taking on more childrearing tasks and mothers working more outside of the home (Fagan, Day, Lamb, & Cabrera, 2014). With increasing evidence for similarities in the quality and quantity of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors, it is important that studies use similar measures for both parents (Fagan et al., 2014). Although many studies examine parents collectively using similar conceptualizations, research suggests that destructive conflict may impact mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices differently. Without a strong parenting alliance, destructive conflict may lead to more inconsistent discipline from mothers (Kaczynski et al., 2006; Mann & MacKenzie, 1996), fathers (Buehler et al., 2006; McCoy, George, Cummings, & Davies, 2013), or both parents equally (Gryczkowski, Jordan, & Mercer, 2010). Children’s perceptions of parents’ inconsistent discipline may mediate the relationship between destructive interparental conflict and children’s depression and conduct problems (Gonzales et al., 2000), though some studies have found only mothers’ inconsistent discipline (and not fathers’) was related to children’s externalizing behavior (Gryczkowski et al., 2010).

Some evidence suggests that fathers’ unsupportive reactions are associated with children’s internalizing symptoms and mothers’ unsupportive reactions with children’s externalizing symptoms (Kaczynski et al., 2006). Other studies suggest that mothers’ psychological intrusiveness may be particularly detrimental (Buehler et al., 2006), and after destructive conflicts, mothers may be more likely to engage in coercive mother–child interactions (Kaczynski et al., 2006) whereas fathers may be more likely to emotionally withdraw from their children (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Although destructive conflict may lead to more ineffective parenting by both parents (Buehler et al., 2006; Kaczynski et al., 2006; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000), inconsistent findings comparing mothers’ and fathers’ specific parenting practices suggest more research is needed (Gryczkowski et al., 2010). Thus, exploring the unique associations of each parent’s problematic parenting remains important, as mothers’ and fathers’ parenting may also differentially affect children’s psychopathology.

Theory and Research on Constructive Conflict

Beyond the importance of examining mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices separately, it is also important to investigate different types of conflict. Most of the research thus far focused exclusively on destructive conflict; however, it isn’t whether parents fight, but how parents fight that matters for children’s development (Goeke-Morey, Cummings, & Papp, 2007). Constructive conflict—marked by cooperation, problem solving, support, physical affection, and working toward a resolution—has also been shown to spill over to other subsystems (Coln et al., 2013) and unlike destructive conflict, has been linked to positive outcomes for children (Goeke-Morey et al., 2007; McCoy et al., 2013). Although constructive conflict promotes positive parenting (Easterbrooks, Cummings, & Emde, 1994; McCoy et al., 2013), few studies have explored whether constructive interparental conflict inhibits those same negative parenting behaviors that are fostered by destructive conflicts (for exceptions, see Coln et al., 2013; McCoy et al., 2013). Of the few studies which have examined constructive conflict in relation to child adjustment, constructive conflict was associated with lower internalizing (Davies, Martin, & Cicchetti, 2012; Zemp, Johnson, & Bodenmann, 2019; Zhou & Buehler, 2019) and externalizing symptoms (Davies et al., 2012). Constructive conflict tactics have also been shown to decrease the probability of aggression in children and adolescents (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2004) and have been linked to more positive behavior in infants (Easterbrooks et al., 1994). However, considering the dearth of studies exploring constructive conflict and children’s symptoms of psychopathology, additional research is necessary.

The Current Study

Although studies have explored problematic parenting in relation to interparental conflict and children’s symptoms of psychopathology, these studies have typically focused on wide age ranges or adolescents (e.g., Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Cui & Conger, 2008; Fauber et al., 1990; Gryczkowski et al., 2010), failed to differentiate mothers’ and fathers’ parenting (e.g., Fauber et al., 1990; Gonzales et al., 2000), or focused solely on destructive conflict (e.g., Buehler et al., 2006; Kaczynski et al., 2006). Although studies have linked destructive conflict to higher levels of problematic parenting practices—like inconsistent discipline, unsupportive reactions, and control through guilt—few studies have explored whether constructive conflict was associated with lower levels of these same parenting practices. Of those studies which have examined constructive conflict and problematic parenting, mother and father reports and multiple problematic parenting practices were combined into a single “negative parenting practices” variable (Coln et al., 2013) or children’s symptoms of psychopathology were not considered (McCoy et al., 2013). Recent studies have explored the interactive effects of destructive and constructive conflict on children’s adjustment (Zemp et al., 2019; Zhou & Buehler, 2019); however, the associations of each type of conflict and each parent’s parenting practices on children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms remains largely uninvestigated.

Therefore, the current longitudinal investigation aims to build upon the extant literature to explore the associations between constructive and destructive conflict, mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices (i.e., inconsistent discipline, unsupportive reactions, and control through guilt), and school-age children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Two sequential mediation models were constructed—one for destructive interparental conflict and another for constructive interparental conflict—using structural equation modeling based on three waves of data collected annually beginning when children were approximately 6 years old. Environmental risks—like interparental conflict and adverse parenting—present in early childhood predict psychopathology in middle childhood (Gach, Ip, Sameroff, & Olson, 2018), making this age group of particular interest. First, destructive interparental conflict was hypothesized to be positively associated with problematic parenting practices in mothers and fathers, whereas constructive interparental conflict was hypothesized to be negatively associated with these same parenting practices. Second, problematic parenting was hypothesized to be associated with higher levels of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Finally, destructive conflict was hypothesized to be indirectly associated with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms through mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices, whereas constructive conflict was hypothesized to be indirectly associated with lower levels of symptoms. Due to inconsistent findings in the literature, no explicit hypotheses were made regarding mothers’ and fathers’ specific problematic parenting practices as explanatory mechanisms.

Method

Participants

Participants in this dual-site study were kindergarten children and their cohabitating parents. To be eligible to participate, two-parent families had to have cohabitated for at least three years and have a child currently enrolled in kindergarten. There were 235 children (106 males, 129 females, Mage = 6.00 years, SD = .48) at Time 1, 220 children (100 males, 120 females, Mage = 6.96 years, SD = .50) at Time 2, and 217 children (101 males, 116 females, Mage = 7.98 years, SD = .53) at Time 3 meeting these criteria. At Time 1, child participants were 70.2% White, 14.5% Black, 13.2% Biracial, and 2.1% Hispanic/Latino. The current sample was generally representative of the communities from which it was drawn, which were 77.99% White, 12.82% Black, 1.51% Biracial/Multiracial, 5.16% Hispanic/Latino, and 2.52% other races (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Most parents had some college, were married, and mothers (Mage = 35.04 years, SD = 5.60, age range: 22–51 years) and fathers (Mage = 36.84 years, SD = 6.14, age range: 22–52 years) reported, on average, living together for 11 years at Time 1 (SD = 4.90). Overall, 94.5% of female parents were biological mothers, 3% were step or adoptive mothers, and 2.5% reported other forms of guardianship (e.g., grandmother or father’s live-in girlfriend). For male parents, 88% were biological fathers, 9.5% were step or adoptive fathers, and 2.5% were other forms of guardianship (e.g., grandfather or mother’s live-in boyfriend). Between Time 1 and Time 3, 18 families dropped out of the study (92% retention rate), with 13 couples (72% of those who dropped) experiencing a divorce or separation during that time. In Time 1, 88.9% of parents reported being married, 89.3% in Time 2, and 88.3% in Time 3. Compared to other family types, married couples tended to be more highly educated (mothers: t(42.20) = −4.32, p < .001; fathers: t(39.97) = −7.11, p < .001) and had been cohabitating for longer than other families, t(29.14) = −3.98, p < .001. In comparisons between families who completed all three time points and those who dropped, there were no differences on any model variables and most demographic characteristics. However, compared to those who dropped, families who completed all three time points had more years of maternal education, t(233) = 3.19, p < .01, and paternal education, t(231) = 3.12, p < .01.

Procedure

Once approval was received from the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Rochester (Study Title: “Family Process, Emotional Security, and Child Adjustment”), participants were recruited at community events and via flyers and postcards. Time 1 data collection began in 1999. At each time point, eligible families participated in two laboratory visits—set approximately two weeks apart—lasting about 2.5 hours. After providing informed consent, mothers and fathers completed a series of interviews, questionnaires, and observational procedures while children completed their own tasks. While one parent was being interviewed, the other parent completed questionnaires in a separate space to maintain confidentiality and prevent sharing of answers. After completing questionnaires, parents engaged in a videotaped dyadic conflict discussion. Parents were informed their discussion would be videotaped, but that the experimenter and their child would remain out of the room for the duration of their discussion. Parents individually brainstormed topics of conflict in their relationship (3 minutes) before deciding together which two topics (one topic from each parent’s list) they felt comfortable discussing on video (2 minutes). Parents were instructed to discuss their chosen topic just as they would in their own home and to try to come to some type of resolution. They then had two 7-minute conflict discussions, one devoted to each of their chosen topics. Constructive and destructive behaviors were later coded from the videotaped observations every 30 s throughout the interactions, based on a scale from 0 (not seen at all) to 2 (two or more occurrences). At the end of each visit, parents were compensated (for a total of $120 at Time 1, $195 at Time 2, and $210 at Time 3) and children were given a small toy (for a total value of $10 at Time 1 and $15 at Times 2 and 3) for their participation.

Measures

Destructive conflict

To create a latent variable of parents’ destructive conflict at Time 1, three assessments—yielding seven manifest indicators total—were utilized. First, mothers and fathers reported their overt hostility in front of their children using the 10-item O’Leary–Porter Scale (OPS; Porter & O’Leary, 1980). Items such as “In every normal relationship there are arguments. What percentage of arguments would you say take place in front of your child?” were rated on this 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), with high scores indicating high levels of conflict in front of child. This scale has shown good convergent validity and test-retest reliability (Porter & O’Leary, 1980) and in the current study, mother and father reports were averaged to create an overall couple “hostility” score (α = .86).

Second, both parents completed the 7-item physical aggression, 8-item verbal aggression, 2-item frequency/severity, and 6-item stonewalling subscales of the Conflicts and Problem-Solving Scales (CPS; Kerig, 1996). The frequency/severity subscale asked parents to indicate the frequency of minor (e.g., spats, get on each other’s nerves) and major conflicts (e.g., big fights, “blow ups”) on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (once a year or less) to 6 (just about every day), whereas the physical aggression (“throw something”), verbal aggression (“raise voice, yell, or shout”), and stonewalling (“withdraw love or affection”) subscales asked parents how often they or their partners used various conflict strategies on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often). Total scores for each parent were created by summing the items on each subscale and creating parental composites for each subscale by averaging mother and father reports. Kerig (1996) reported moderate test-retest reliability and good convergent and discriminant validity, and in the current study, all subscales indicted good-to-excellent reliability across reporters, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .74 to .92.

Third, coders rated each parent’s verbal and nonverbal anger from the videotaped dyadic conflict discussions. Verbal anger included speaking in an angry tone of voice, yelling, or making angry statements/comments (e.g., “I don’t even feel like dealing with you.”), whereas nonverbal anger included expressing anger or frustration without words (e.g., angry sighs, shaking head in disgust, threatening looks, cold stares, rolling eyes). Coders demonstrated acceptable inter-rater reliability for nonverbal anger (ICC = .88 for mothers, 1.00 for fathers) and verbal anger (ICC = .97 for mothers, 1.00 for fathers). Scores were summed across both interactions to create a separate score for both mothers’ and fathers’ use of each of the destructive behaviors, and then mothers’ and fathers’ behaviors were averaged to create one couple score for both nonverbal and verbal anger.

Constructive conflict

To create a latent variable of parents’ constructive conflicts at Time 1, two assessments—leading to five manifest indicators—were utilized. First, mothers and fathers each completed the 6-item cooperation subscale and the 13-item resolution subscale of the Conflicts and Problem-Solving Scales (Kerig, 1996). Using the same scale noted previously, each parent reported on their own and their partner’s use of cooperation (e.g., “listen to the other’s point of view”) and resolution (e.g., “we feel that we have resolved it or come to an understanding”) and total scores for each parent were created by summing the items on each subscale and then to create parental composites for each subscale, mother and father reports were averaged (α = .89 for cooperation, α = .90 for resolution).

Second, dyadic conflict discussions were also coded for support (ICC = .94 for mothers, .89 for fathers), problem solving (ICC = .83 for mothers, .93 for fathers), and physical affection (ICC = .72 for mothers, .71 for fathers). Support included behaviors like reassuring the spouse that one is listening, trying to understand, or saying they may have a good point (even if one does not necessarily agree with the point); whereas problem solving included behaviors like suggesting a possible solution and physical affection consisted of physical expressions of caring without using words (e.g., hugging, kissing, holding hands). Similar to the destructive conflict codes, scores were summed across both interactions to create a separate score for both mothers’ and fathers’ use of support, problem solving, and physical affection, and then mothers’ and fathers’ behaviors were averaged to create one couple score for each constructive behavior.

Problematic parenting practices

To assess parents’ use of various problematic parenting practices at Time 2, a few measures were utilized. First, mothers and fathers completed the 6-item inconsistent discipline subscale of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton, Frick, & Wootton, 1996). Each parent reported on their own and their partner’s use of inconsistent discipline (e.g., “You threaten to punish your child and then do not actually punish him/her”) using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The APQ has been shown to have adequate test-retest reliability and convergent validity (Shelton et al., 1996) and in the current study, self-reported and partner-reported items were averaged with high scores indicating more inconsistent discipline (with combined self- and partner-reported items for each parent: α = .75 for mothers and α = .77 for fathers).

Second, mothers and fathers reported their responsiveness to their child’s displays of negative affect during stressful situations with the Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; Fabes et al., 1990). The CCNES presents 12 hypothetical scenarios for which parents indicate the likelihood of responding to the child’s distress in both supportive ways and unsupportive ways. Each scenario asks parents to rate their likelihood of responding in six different ways using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) and a mean score is calculated for each subscale. To capture unsupportive reactions for each parent, mothers and fathers reported on their punitive reactions (e.g., “send my child to his/her room to cool off”), minimization reactions (e.g., “tell my child that he/she is over-reacting”), and distressed reactions (e.g., “get angry at my child”) and these subscales were summed to create an overall measure of each parent’s unsupportive reactions. In previous studies, the CCNES has been shown to have sound test-retest reliability and construct validity (Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg, & Madden-Derdich, 2002) and in the current study, internal consistency was acceptable with α = .85 for mothers and α = .90 for fathers.

Third, mothers and fathers completed the 5-item control through guilt subscale of the Parent Version of the Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (PV-CRPBI; Margolies & Weintraub, 1977). Each parent reported on their own and their partner’s use of control through guilt (e.g., “you tell your child that s/he would do what you want if s/he loved you”) using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The 10 items (five self-reported, five partner-reported) were averaged with high scores indicating more control through guilt. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .74 for mothers and .75 for fathers.

Symptoms of psychopathology

Finally, to assess children’s symptoms of psychopathology at Time 3, mothers and fathers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). Parents evaluated 33 statements about their children’s externalizing behaviors (i.e., aggression and delinquency, with items like “lying and cheating”) and 33 statements about their internalizing behaviors (i.e., depression, anxiety, withdrawal, and somatic complaints, with items like, “nervous, high strung or tense”) using a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). The CBCL has been shown to have high internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2002). In the current study, mother and father reports were averaged to create a composite indicator of children’s internalizing (α = .88) and externalizing symptoms (α = .91).

Data Analysis Plan

Rather than focusing on change over time, the goal of the current study was to explore prospective relations among interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms using longitudinal data. Longitudinal associations were tested as indirect effects using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) in Mplus (Version 7.4, Muthén & Muthén, 2015) and the robust maximum likelihood approach—which corrects standard errors for multivariate non-normality while using full information maximum likelihood estimation—was selected due to children’s symptoms of psychopathology being negatively skewed. This approach to missing data handles high rates of missingness in structural equation models without sacrificing power (Enders, 2010). Of the 15 families who dropped between Time 1 and Time 2, 11 returned for Time 3 (73.3%). Of the 235 participating families, only four (1.7%) dropped after Time 1 and did not return for Times 2 or 3. Initial marital status, mother education, and father education were included as auxiliary variables (Enders, 2010). Using structural equation modeling, two sequential mediation models were constructed using Time 1 interparental conflict (destructive in the first model, constructive in the second model), mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices (inconsistent discipline, unsupportive reactions, and control through guilt) at Time 2, and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at Time 3. Mother and father reports of the same variable were significantly positively correlated (.28 < r < .64), supporting the use of averages to capture typical values for each family. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict (zero-order correlations shown in Table 1) were investigated in separate models to allow for the examination of their associations to mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices and children’s symptoms of psychopathology.

Table 1.

Zero-order Correlations for Constructive and Destructive Interparental Conflict

| Constructive interparental conflict |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperation | Resolution | Problem solvinga | Supporta | Physical affectiona | |

| Destructive interparental conflict | |||||

| Hostility | −.52 | −.69 | −.08 | −.07 | −.18 |

| Physical aggression | −.39 | −.51 | −.17 | −.09 | −.08 |

| Verbal aggression | −.48 | −.68 | −.13 | −.03 | −.10 |

| F requency/severity | −.40 | −.58 | −.06 | .06 | −.07 |

| Stonewalling | −.55 | −.63 | −.16 | −.08 | −.07 |

| Verbal angera | −.30 | −.41 | −.16 | −.12† | −.08 |

| Nonverbal angera | −.09 | −.06 | −.25 | −.21 | −.08 |

Note.

Observed behaviors.

Bolded values indicate p < .05.

p < .10.

Hypothesized models were determined to have relatively good fit with the observed data if CFI and TLI values were greater than .95, and RMSEA and SRMR values were smaller than .08 and .06, respectively (Little, 2013). In the first model, a latent variable for destructive conflict was constructed with manifest variables of combined parent reports of hostility, physical aggression, verbal aggression, frequency/severity, stonewalling, verbal anger, and nonverbal anger. In the second model, parent reports of cooperation, resolution, problem solving, support, and physical affection were combined to create a latent variable of constructive conflict. Although observational measures of constructive and destructive conflict showed lower loadings onto latent constructs and were less likely to be correlated to other variables, these values are not unexpected (Lorenz, Melby, Conger, & Xu, 2007), as these behaviors tend to be more subtle and infrequent but contribute necessary depth to depictions of each type of conflict beyond questionnaires alone. For that reason, observations of interparental conflict were included in each model. In both models, to account for shared method variance, Time 1 interparental conflict measures of the same type (i.e., questionnaires or coded observations) were allowed to covary. In addition, Time 2 mother and father reports of the same parenting construct (e.g., control through guilt) were allowed to covary, as mothers’ and fathers’ caregiving practices tend to correlate (Fagan et al., 2014), and mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices were allowed to covary within parent, as parents may display multiple problematic parenting practices simultaneously (McCoy et al., 2013). Similarly, Time 3 internalizing and externalizing symptoms were allowed to covary, as these tend to be highly comorbid (Cosgrove et al., 2011).

Results

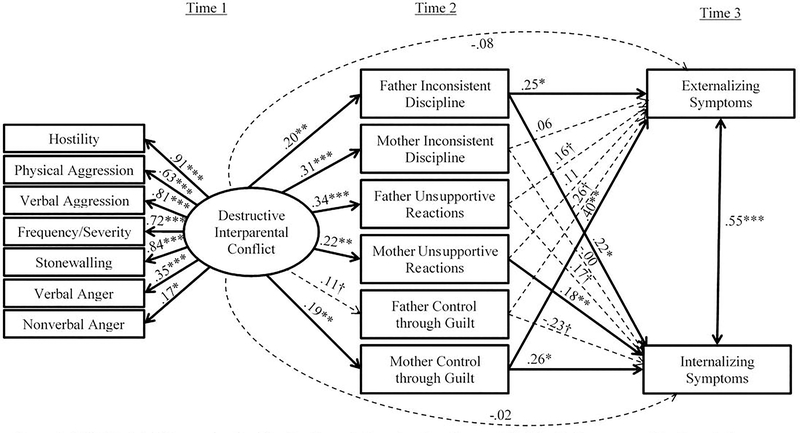

Using structural equation modeling in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2015), a sequential mediation model (N = 235) with destructive interparental conflict, mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting, and child symptoms of psychopathology was constructed (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics and correlations). The model (Figure 1) demonstrated acceptable fit to the data, χ2(65) = 95.15, p < .01, RMSEA = .04, 90% CI [.02, .06], CFI = .98, TLI = .96, SRMR = .05. Direct pathways suggested that destructive conflict at Time 1 was linked with higher levels of problematic parenting practices at Time 2; specifically, more inconsistent discipline, unsupportive reactions to children during stressful situations, and maternal attempts at controlling the child through guilt. Direct pathways from destructive interparental conflict to children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms were nonsignificant. Further, indirect effects showed that mothers’ control through guilt served as a significant intervening process between destructive conflict and children’s externalizing symptoms (B = .10, SE = .05, β = .07, p < .05). Therefore, findings from this model suggest that destructive interparental conflict may directly relate to mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices, but only mothers’ control through guilt operated as an explanatory mechanism between destructive interparental conflict and children’s externalizing symptoms.

Table 2.

Zero-order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Destructive Conflict, Problematic Parenting Practices, and Child Symptoms of Psychopathology

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destructive interparental conflict | |||||||||||||||

| 1. Hostility | 1.3% | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Physical aggression | .56 | .4% | |||||||||||||

| 3. Verbal aggression | .73 | .59 | 1.3% | ||||||||||||

| 4. Frequency/severity | .68 | .43 | .69 | 3.4% | |||||||||||

| 5. Stonewalling | .55 | .54 | .69 | .56 | 2.6% | ||||||||||

| 6. Verbal angera | .33 | .25 | .26 | .15 | .24 | .85% | |||||||||

| 7. Nonverbal angera | .14 | .07 | .16 | .17 | .14 | .17 | .85% | ||||||||

| Problematic parenting practices | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Father ID | .18 | .18 | .12† | .07 | .19 | −.09 | .10 | 5.5% | |||||||

| 9. Mother ID | .31 | .16 | .18 | .20 | .26 | −.01 | .13† | .63 | 5.5% | ||||||

| 10. Father USR | .33 | .24 | .20 | .18 | .25 | .06 | .16 | .16 | .20 | 22.1% | |||||

| 11. Mother USR | .23 | .06 | .15 | .19 | .10 | .10 | .19 | .08 | .23 | .25 | 12.8% | ||||

| 12. Father CTG | .06 | .13 | .07 | .05 | .14 | .03 | .07 | .29 | .16 | .19 | .10 | 6.0% | |||

| 13. Mother CTG | .16 | .18 | .08 | .11 | .17 | .08 | .07 | .30 | .26 | .27 | .17 | .86 | 5.1% | ||

| Symptoms of psychopathology | |||||||||||||||

| 14. Externalizing | .10 | .02 | .03 | .10 | .10 | −.04 | .04 | .34 | .30 | .25 | .21 | .18 | .29 | 14.0% | |

| 15. Internalizing | .14† | .10 | .08 | .15 | .10 | .05 | .05 | .28 | .24 | .25 | .26 | .09 | .18 | .63 | 14.0% |

| Mean | 10.26 | 1.73 | 12.11 | 8.19 | 6.59 | 1.44 | .88 | 13.03 | 13.77 | 8.55 | 7.69 | 11.05 | 11.96 | 9.06 | 7.76 |

| SD | 4.57 | 2.01 | 3.72 | 2.77 | 2.23 | 5.03 | 1.13 | 2.72 | 2.67 | 2.14 | 1.74 | 2.56 | 2.57 | 5.86 | 5.45 |

Note. ID = inconsistent discipline. USR = unsupportive reactions. CTG = control through guilt.

Observed behaviors. Percentage of missing data for each variable included along the diagonal.

Bolded values indicate p < .05.

p< .10.

Figure 1.

SEM Model of Destructive Conflict, Problematic Parenting Practices, and Children’s Symptoms of Psychopathology.

Model fit: χ2(65) = 95.15, p < .01, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .98, TLI = .96, SRMS = .05. Standardized estimates Shown.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

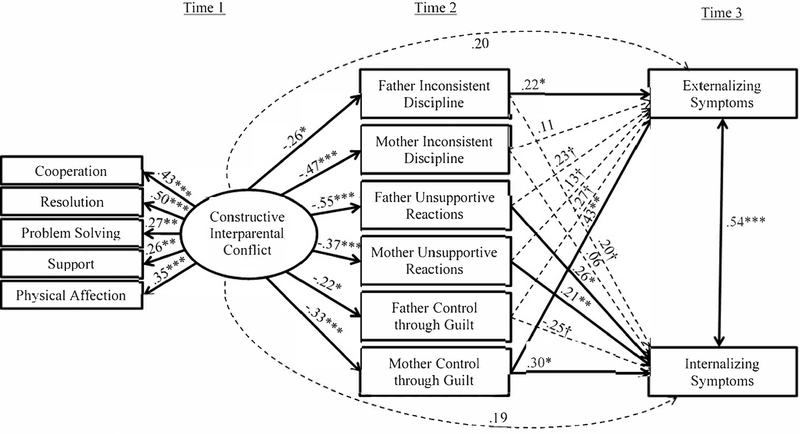

Next, a second sequential mediation model (N = 235) was constructed, this time with mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting as the intermediary processes between constructive conflict and child symptoms of psychopathology (see Table 3 for descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations). The model (Figure 2) demonstrated acceptable fit to the data, χ2(43) = 40.94, p = .56, RMSEA = .00, 90% CI [.00, .04], CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, SRMR = .04. As expected, direct pathways showed that constructive conflict at Time 1 was linked with lower levels of problematic parenting practices at Time 2. Similar to the previous model, direct pathways from constructive conflict to children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms were nonsignificant.

Table 3.

Zero-order Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Constructive Conflict, Problematic Parenting Practices, and Child Symptoms of Psychopathology

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructive interparental conflict | |||||

| 1. Cooperation | .85% | ||||

| 2. Resolution | .69 | 4.3% | |||

| 3. Problem solvinga | .16 | .17 | .85% | ||

| 4. Supporta | .14 | .10 | .24 | .85% | |

| 5. Physical affectiona | .13† | .15 | .20 | .14 | .85% |

| Problematic parenting practices | |||||

| 6. Father ID | −.07 | −.06 | −.04 | −.06 | −.15 |

| 7. Mother ID | −.22 | −.22 | −.11 | −.09 | −.22 |

| 8. Father USR | −.26 | −.35 | −.10 | −.21 | .15† |

| 9. Mother USR | −.13† | −.19 | −.03 | −.00 | −.09 |

| 10. Father CTG | .07 | .02 | −.01 | −.07 | −.11 |

| 11. Mother CTG | −.04 | −.08 | −.02 | −.05 | −.13 |

| Symptoms of psychopathology | |||||

| 12. Externalizing | −.06 | −.09 | −.03 | .00 | −.07 |

| 13. Internalizing | −.05 | −.07 | −.02 | .03 | −.09 |

| Mean | 14.57 | 1.99 | 5.18 | .76 | 2.09 |

| SD | 2.22 | 5.36 | 4.37 | 1.11 | 6.24 |

Note. ID = inconsistent discipline. USR = unsupportive reactions. CTG = control through guilt. Correlations and descriptive statistics already presented in Table 2 have been omitted here.

Observed behaviors. Percentage of missing data for each variable included along the diagonal.

Bolded values indicate p < .05.

p < .10.

Figure 2.

SEM Model of Destructive Conflict, Problematic Parenting Practices, and Children’s Symptoms of Psychopathology.

Model fit: χ2(43) = 40.94, p > .05, RMSEA = .00, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, SRMS = .04. Standardized estimates Shown.

†p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Indirect effects showed that mothers’ unsupportive reactions functioned as an intermediary process between constructive interparental conflict and child internalizing symptoms (B = −.45, SE = .25, β = −.08, p < .05), indicating that constructive conflict at Time 1 was associated with lower levels of maternal unsupportive behaviors to children’s negative emotions at Time 2, which, in turn, were associated with fewer internalizing symptoms at Time 3. In addition, indirect effects showed that mothers’ control through guilt was a significant intervening mechanism between constructive conflict and children’s externalizing symptoms (B = −.89, SE = .55, β = −.14, p < .05), meaning that constructive conflict was associated with fewer externalizing symptoms via lower levels of mothers’ control through guilt. Together, these findings suggest that constructive conflict may prospectively predict lower levels of problematic parenting practices, and that mothers’ unsupportive reactions and control through guilt may subsequently be associated with lower levels of children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, respectively.

Discussion

Results of the current study suggest that the type of conflict—namely, constructive or destructive—matters when exploring spillover from the interparental relationship to problematic parenting practices and how these relate to children’s symptoms of psychopathology. Direct effects showed that destructive interparental conflict was linked with higher levels of mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices a year later, whereas constructive interparental conflict was related to lower levels of these same practices. Results of the current study also stress the importance of differentiating between mothers and fathers, as interparental conflict may relate to their parenting practices differently, despite similarities in how mothers and fathers parent (Fagan et al., 2014). Though various direct effects between mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms a year later were significant, indirect effects showed that mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices differed in their associations to interparental conflict and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. Specifically, mothers’ control through guilt was a significant intervening process between constructive and destructive interparental conflict and children’s externalizing symptoms, whereas mothers’ unsupportive reactions were a significant explanatory mechanism between constructive interparental conflict and children’s internalizing symptoms.

Taken together, these findings suggest that spillover from the interparental relationship may be positive or negative depending on whether parents’ conflicts are constructive or destructive. Results of the current study are in line with past spillover research and provide additional insight into the links between interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. For example, destructive interparental conflict has been consistently associated with higher levels of problematic parenting by mothers and fathers (Kaczynski et al., 2006) and these parenting behaviors explain the relationship between interparental conflict and children’s maladjustment (Fauber et al., 1990; Gonzales et al., 2000; Kaczynski et al., 2006). In the current study, however, no indirect effects were found for fathers, suggesting other factors may better explain the relationship between interparental conflict and children’s psychopathology than fathers’ problematic parenting practices. Because mothers tend to spend more time as the primary caregiver (Fagan et al., 2014), their problematic parenting may pose more of a threat to child psychopathology, with the results here supporting this. A previous meta-analysis suggested that youth in middle childhood and adolescence may be the most vulnerable to spillover effects (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000) and the current study—which explored these spillover effects over a period of three years beginning when children were 6 years old—supported this, with results indicating that children in this age group may display higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms as a result of problematic parenting.

These results call attention to the importance of examining parents’ regulatory behavior and their own anxiety and distress in conceptualizing relations between forms of interparental conflict and problematic parenting behaviors. Pertinent to this issue, Cummings and Davies’ (2010) theoretical model of emotional security as reflecting regulatory processes, including emotional regulation (e.g., anxiety and distress), in both marital and parent–child relationships has been advanced as an explanation for spillover relationships. For example, destructive conflict may increase adults’ relationship insecurity whereas constructive interparental conflict may increase adults’ relationship security, with implications in both instances for the likelihood of problematic parenting. Explicit tests of parents’ regulatory behavior and their own anxiety and distress as an explanatory model for these boundary intrusions (i.e., spillover, e.g., Davies et al., 2009) are an important direction for future research.

In the current study, no direct effects were found from constructive and destructive conflict to children’s symptoms of psychopathology; however, this result is comparable to other studies (Coln et al., 2013; Davies et al., 2012) and understandable considering many children who are exposed to interparental conflict do not develop psychopathology (Cummings & Davies, 2010). In addition, significant indirect effects showed that destructive conflict was prospectively associated with higher control through guilt from mothers, which in turn was related to higher levels of children’s externalizing symptoms. These findings corroborate previous studies showing that psychological control mediated the relationship between destructive conflict and children’s externalizing symptoms, although other studies found links to internalizing symptoms as well (Buehler et al., 2006; Coln et al., 2013; Kaczynski et al., 2006). Moreover, current results—like those of Buehler et al. (2006)—suggest that mothers’ control through guilt may be particularly damaging and warrants further investigation. Perhaps mothers were left feeling somewhat helpless after their destructive conflicts with their husbands and this negativity spilled over to the parent–child relationship with mothers trying to control their children’s undesirable behaviors by inducing guilt. In response to this problematic parenting practice, children have been shown to exhibit oppositionality and aggression (Kaczynski et al., 2006) and results of the current study further support this.

Although few previous studies have examined constructive conflict in explorations of spillover, results of the current study point to these behaviors as a potential protective factor and worthy of additional investigation. For instance, significant associations were found between constructive interparental conflict, mothers’ unsupportive reactions, and children’s internalizing symptoms, as well as associations between constructive conflict, mothers’ control through guilt, and children’s externalizing symptoms. Examinations of interparental conflict have historically conceptualized constructive behaviors as those which elicit positive responses from children (Cummings & Davies, 2010); however, results of the current study indicate that constructive conflict may also elicit positive responses from parents or—at the very least—fewer negative reactions. If the negativity of destructive conflicts can spill over into the parent–child relationship via parenting, it makes sense that the positivity of constructive conflicts can do the same and results of the current study further support that all spillover isn’t necessarily negative.

Past research has linked constructive conflict and positive (i.e., warm) parenting (Cummings & Davies, 2010), but findings presented here show that constructive conflict may also predict lower levels of problematic parenting a year later. Because unresponsive parenting and parental rejection can lead to feelings of insecurity and internalizing behaviors (Cui & Conger, 2008; Kaczynski et al., 2006), reducing these unsupportive reactions may positively impact child functioning. As the present results show, if constructive conflict inhibits mothers’ unsupportive reactions—like minimization, displaying distress, or punishing the child—children may be less likely to develop internalizing symptoms. Therefore, in the current study, support was found for both positive and negative spillover, such that the negativity of destructive conflicts tended to spill over into the parent–child relationship via problematic parenting, whereas constructive conflict was associated with lower levels of these negative practices.

In addition to extending the literature on interparental conflict, parenting, and child psychopathology, the present study has numerous methodological strengths. For example, although spillover theory also encompasses positive relations between constructive interparental conflict and parenting, compared to destructive interparental conflict and parenting, their associations have been studied less frequently and even less so with respect to children’s adjustment (Coln et al., 2013). Moreover, a methodological limitation of most interparental conflict research is a lack of direct observation of these interactions (Cui & Conger, 2008); however, the current study included dyadic observations of conflict and coded for both constructive and destructive behaviors. Additionally, rather than relying on a single reporter, which can lead to method bias (Cui & Conger, 2008; Gryczkowski et al., 2010), the present study included mother and father reports of all study variables, and parenting measures combined self and other partner reports to reduce bias and create a more balanced view of each parent’s behavior. These combined reports for each problematic parenting variable and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, as well as the inclusion of latent constructs for constructive and destructive conflict, provided multidimensional views of the family.

Despite these methodological strengths, the current multi-method, multi-reporter study does have its limitations. First, sequential mediation modeling is statistically similar to cross-sectional investigations (Mitchell & Maxwell, 2013). However, the inclusion of longitudinal data does allow for the temporal ordering of variables, which is a decided improvement over cross-sectional designs (Cui & Conger, 2008). To provide more rigorous tests of longitudinal mediation, future studies should consider the addition of autoregressive controls or cross-lagged models (Mitchell & Maxwell, 2013). Due to small longitudinal changes in study variables and model identification issues, we were not able to institute these more rigorous tests in the current study. Second, although some studies with larger samples investigated constructive and destructive conflict in the same model (e.g., Zemp et al., 2019; Zhou & Buehler, 2019), the current study utilized two separate models due to identification issues. Recent research suggests that in the presence of destructive conflict, constructive conflict may have differentiated associations to children’s symptoms of psychopathology (Zhou & Buehler, 2019). However, exploring each type of conflict independently is still important, as the associations between constructive conflict and children’s symptoms of psychopathology may be overshadowed by parents’ destructive conflicts when both forms of conflict are investigated concurrently (Coln et al., 2013; Davies et al., 2012). Third, the current study only examined negative forms of parenting. Past research has identified positive parenting practices, like warmth and sensitivity, as protective factors against the development of psychopathology (Cummings & Davies, 2010), yet few studies have explored whether constructive conflict promotes and destructive conflict diminishes the development of these positive parenting tactics. Therefore, future studies exploring a wider range of parenting practices would add valuable insight to the literature. Finally, the sample of the current study was fairly homogeneous, potentially impacting generalizability. To ameliorate this, future studies may consider using larger, more diverse samples. Despite these limitations, the current study holds promise for understanding the relations of interparental conflict, parenting, and children’s psychopathology and encourages future investigations of how mothers and fathers may differ.

In sum, results of the current study point to the importance of examining families as systems and provides further support of the spillover hypothesis. Differentiating mothers’ and fathers’ problematic parenting practices—as well as distinguishing between constructive and destructive interparental conflict—remain important, as each can have distinct relations to broader family functioning. Finally, results of the current study further stress that it isn’t whether parents fight, but how they fight that matters for children’s development (Goeke-Morey et al., 2007) and how these conflicts spill over into mothers’ and fathers’ parenting is relevant to investigations of children’s symptoms of psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

The current manuscript is an original conceptualization; however, portions of the same longitudinal dataset have been previously disseminated. This paper is an extension of work presented at the Society for Research in Child Development Special Topics Meeting on New Conceptualizations in the Study of Parenting-At-Risk. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH57318) awarded to Patrick T. Davies and E. Mark Cummings. We are grateful to the children and parents who participated in this project. We express our appreciation to project staff, graduate students, and undergraduates at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Rochester who worked on this project.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist: 4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, & Rescorla LA (2002). Ten-year comparison of problems and competencies for national samples of youth: Self, parent, and teacher reports. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10, 194–203. doi: 10.1177/10634266020100040101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Benson MJ, & Gerard JM (2006). Interparental hostility and early adolescent problem behavior: The mediating role of specific aspects of parenting. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 265–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00132.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, & Gerard JM (2002). Marital conflict, ineffective parenting, and children’s and adolescents’ maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 78–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00078.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coln KL, Jordan SS, & Mercer SH (2013). A unified model exploring parenting practices as mediators of marital conflict and children’s adjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44, 419–429. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0336-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove VE, Rhee SH, Gelhorn HL, Boeldt D, Corley RC, Ehringer MA, … Hewitt JK (2011). Structure and etiology of cooccurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, & Conger RD (2008). Parenting behavior as mediator and moderator of the association between marital problems and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 261–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00560.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, & Davies PT (2010). Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, & Papp LM (2004). Everyday marital conflict and child aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 191–202. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000019770.13216.be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Martin MJ, & Cicchetti D (2012). Delineating the sequelae of destructive and constructive interparental conflict for children within an evolutionary framework. Developmental Psychology, 48, 939–955. doi: 10.1037/a0025899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Woitach MJ, & Cummings EM (2009). A process analysis of the transmission of distress from interparental conflict to parenting: Adult relationship security as an explanatory mechanism. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1761–1773. doi: 10.1037/a0016426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Cummings EM, & Emde R (1994). Young children’s responses to constructive marital disputes. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, 160–169. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.8.2.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engfer A (1988). The interrelatedness of marriage and the mother–child relationship In Hinde RA & Stevenson-Hinde J (Eds.), Relationships within families: Mutual influences (pp. 104–118). Oxford, UK: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, & Burman B (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent–child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, & Bernzweig J (1990). The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale: Procedures and scoring. Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, & Madden-Derdich DA (2002). The Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES): Psychometric properties and relations with children’s emotional competence. Marriage & Family Review, 34, 285–310. doi: 10.1300/J002v34n03_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Day R, Lamb ME, & Cabrera NJ (2014). Should researchers conceptualize differently the dimensions of parenting for fathers and mothers? Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6, 390–405. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fauber R, Forehand R, Thomas AM, & Wierson M (1990). A mediational model of the impact of marital conflict on adolescent adjustment in intact and divorced families: The role of disrupted parenting. Child Development, 61, 1112–1123. doi: 10.2307/1130879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gach EJ, Ip KI, Sameroff AJ, & Olson SL (2018). Early cumulative risk predicts externalizing behavior at age 10: The mediating role of adverse parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 32, 92–102. doi: 10.1037/fam0000360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, & Papp LM (2007). Children and marital conflict resolution: Implications for emotional security and adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 744–753. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Pitts SC, Hill NE, & Roosa MW (2000). A mediational model of the impact of interparental conflict on child adjustment in a multiethnic, low-income sample. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 365–379. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.14.3.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryczkowski MR, Jordan SS, & Mercer SH (2010). Differential relations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting practices and child externalizing behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 539–546. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9326-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski KJ, Lindahl KM, Malik NM, & Laurenceau J-P (2006). Marital conflict, maternal and paternal parenting, and child adjustment: A test of mediation and moderation. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 199–208. doi: 10.1037/08933200.20.2.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK (1996). Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The Conflicts and Problem-Solving Scales. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 454–473. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.4.454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, & Buehler C (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations, 49, 25–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Melby JN, Conger RD, & Xu X (2007). The effects of context on the correspondence between observational ratings and questionnaire reports of hostile behavior: A multitrait, multimethod approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 498–509. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann BJ, & MacKenzie EP (1996). Pathways among marital functioning, parental behaviors, and child behavior problems in school-age boys. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 183–191. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2502_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margolies PJ, & Weintraub S (1977). The revised 56-item CRPBI as a research instrument: Reliability and factor structure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33, 472–476. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy KP, George MRW, Cummings EM, & Davies PT (2013). Constructive and destructive marital conflict, parenting, and children’s school and social adjustment. Social Development, 22, 641–662. doi: 10.1111/sode.12015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MA, & Maxwell SE (2013). A comparison of the cross-sectional and sequential designs when assessing longitudinal mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 48, 301–339. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2013.784696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2015). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Porter B, & O’Leary KD (1980). Marital discord and childhood behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 8, 287–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00916376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, & Wootton J (1996). Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 317–329. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2503_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. doi: 10.2307/270723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Profile of general demographic characteristics [Summary file 1]. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov

- Zemp M, Johnson MD, & Bodenmann G (2019). Out of balance? Positivity–negativity ratios in couples’ interaction impact child adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 55, 135–147. doi: 10.1037/dev0000614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, & Buehler C (2019). Marital hostility and early adolescents’ adjustment: The role of cooperative marital conflict. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39, 5–27. doi: 10.1177/0272431617725193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]