Abstract

During the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Hong Kong in 2003, patients were treated with very high doses of corticosteroid and ribarivin. The detrimental effects of such treatment on the bone mineral density (BMD) of SARS patients are unknown.

To compare the BMD of SARS patients with normal range data, a cross-sectional survey was conducted. The bone mineral density of 224 patients with SARS, who were treated with an average of 2753 mg (SD = 2152 mg) prednisolone and 29,344 mg (SD = 15,849 mg) of ribarivin was compared to normal data. Six percent of men had a hip BMD Z score of ≤−2 (P = 0.057 for testing the hypothesis that >2.5% of subjects should have a Z score of ≤−2). Moreover, there was a negative association (r = −0.25, P = 0.023) between the duration of steroid therapy and BMD in men.

We conclude that male SARS patients had lower BMD at the hip than normal controls, and this could be attributed to prolonged steroid therapy.

Keywords: SARS, Steroid, Bone mineral density, Hong Kong

Introduction

In the spring of 2003, the world was overwhelmed by an outbreak of a new infectious disease—the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). By the end of July 2003, a total of 8098 patients had contracted the disease, 96% of whom were living in Asia. With a total of 1755 cases and a case fatality rate of more than 17%, Hong Kong was the hardest hit city in Asia. Local clinicians had to face the major challenge of having to devise a treatment scheme for the disease, even before its origin was known [1], [2]. SARS patients ended up being prescribed very high doses of corticosteroid and ribavirin, despite their potential detrimental effects to bones and joints. In order to document the possible adverse effects of such treatment on the bone mineral density (BMD) of SARS patients, a cross-sectional study, in which the BMD of SARS patients were compared to normal controls, was conducted.

Materials and methods

The sample for this study was the 224 SARS patients who were admitted to Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong. This hospital is where the SARS outbreak had originated.

The diagnosis of SARS was based on the following clinical criteria: A person with a history of fever (≥38°C); one or more symptoms of lower respiratory tract illness (cough, difficulty in breathing, shortness of breath); radiographic evidence of lung infiltrates consistent with pneumonia or RDS or without an identifiable cause.

These SARS patients were treated for the first 2 days with broad spectrum antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia, according to the American Thoracic Society Guidelines. Initial treatment consisted of intravenous cefotaxime 1 g every 6 h with either oral levofloxacin 500 mg daily or clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily. Oseltamivir was also given to the initial patients to treat possible influenza infection. Clinical symptoms, blood oxygen saturation, and chest radiograph were assessed daily. If fever persisted after 48 h, patients were given a combination of ribavirin and “low-dose” corticosteroid therapy commencing on Days 3–4 (oral ribavirin as a loading dose of 2.4 g followed by 1.2 g three times daily and prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg body weight per day), whereas those with dyspnea were treated with intravenous ribavirin (400 mg every 8 h), combined with hydrocortisone (100 mg every 8 h). Pulses of high-dose methylprednisolone (0.5 g IVI for three consecutive days) were given as a response to persistent or recurrent fever, and radiographic progression of lung opacity with or without hypoxemia, despite initial combination therapy. Further pulses of methylprednisolone were given if there was no clinical or radiological improvement, at a total dose of up to 3 g. The intention was to continue with the combination of ribavirin and “low-dose” corticosteroid for up to 12 days, when there was complete resolution of lung opacity. Those who became afebrile, but with incomplete radiological resolution, were given oral ribavirin 600 mg t.i.d. and prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg body weight per day for at least one further week.

The current research protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Subjects were approached by a research nurse by phone, and invited to participate in the study. After informed consent was obtained, clinical data were retrieved using a computerized hospital discharge record system, and clinical records were studied in details.

The bone mineral density (BMD) of all subjects were measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry. On average, patients had their BMD measured at 197 days after being diagnosed as SARS patients. (median = 195 days and range = 149–231 days). A Hologic QDR-4500 machine (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA) was used. The CV in our laboratory was 1% at both sites [3]. The BMD of SARS patients were compared to age- and sex-specific normal range data from our center. The normal range was previously established from healthy volunteers. The BMD of SARS patients were presented as Z scores. To test if more than 2.5% of SARS patients had a BMD of Z score −2 or lower, a 1-sided exact binominal test was used. The total number of days of bed rest was unknown in patients.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of SARS patients in this study are shown in Table 1 . The mean age of patients was 37.6 years (range 21 to 85 years). It can be seen that 77.2% of men and 73.1% of women had received high-dose intravenous steroid therapy. Assuming that 1 mg of prednisolone was equivalent to 4 mg hydrocortisone (or 0.8 mg of methyl prednisolone), male patients had an average daily dose of 176 mg (SD = 109 mg), with an average cumulative dose of 2931 mg (SD = 2085 mg) of prednisolone; while female patients had an average daily dose of 152 mg (SD = 111 mg); and an average cumulative dose of 2648 mg (SD = 2191 mg) of prednisolone. Moreover, both men and women were treated by high-dose ribavirin therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of SARS patients [percentages, or mean (SD)] who had been on steroid therapy

| Men (N = 83) | Women (N = 141) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–29 | 24.1% | 37.6% |

| 30–39 | 43.4% | 26.2% |

| 40–49 | 10.8% | 17.0% |

| 50–59 | 14.5% | 16.3% |

| 60 or above | 7.2% | 2.8% |

| Duration of disease (days) | 23 (10) | 23 (10) |

| Drug treatment protocola | ||

| I | 12.1% | 18.4% |

| II | 10.8% | 8.5% |

| III | 38.6% | 42.6% |

| IV | 38.6% | 30.5% |

| Prednisolone equivalent dose per day (mg) | 176 (109) | 152 (111) |

| Duration of prednisolone equivalent dose (days) | 17 (10) | 17 (10) |

| Cumulative prednisolone equivalent dose (mg) | 2931 (2,085) | 2648 (2,191) |

| Cumulative ribavirin dose (mg) | 24,326 (14,605) | 32,298 (15,857) |

| Admission to intensive care unit | ||

| Yes | 24.1% | 11.4% |

| Bone mineral density (g/cm2) | ||

| Total hip | 0.91 (0.15) | 0.87 (0.12) |

| Total spine | 0.94 (0.13) | 0.96 (0.11) |

I: Oral ribavirin as a loading dose of 2.4 g stat followed by 1.2 g three times daily and prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg body weight per day. II: Intravenous ribavirin (400 mg every 8 h) combined with hydrocortisone (100 mg every 8 h). III: Pulses of high-dose methylprednisolone (0.5 g IVI for three consecutive days) added on initial combination therapy. IV: Further pulses of methylprednisolone, up to a total of 3 g/day.

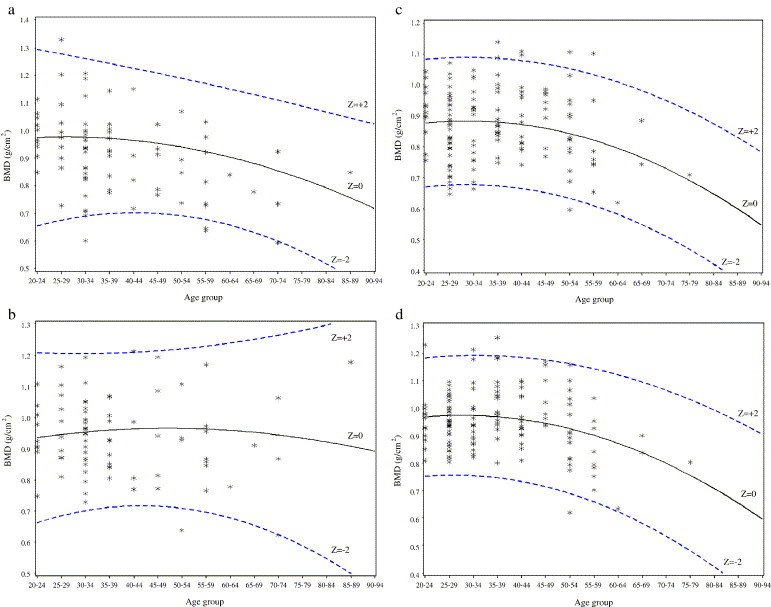

On average, patients had their BMD measured at 197 days after being diagnosed as SARS patients (SD = 18, median = 195 days, range 149–231 days). The Z score for BMD at the total hip and spine for SARS patients are shown in Fig. 1 (a–d) and Table 2 . In men, there was a trend for SARS patients to have negative BMD Z scores. Six percent and 3.7% of men had a BMD Z score of ≤−2 at the total hip and spine, respectively (P = 0.057 for testing the hypothesis that >2.5% of subjects should have a Z score of ≤−2 at the total hip). In men, the Spearman correlation coefficients between BMD and the following variables are as follows: duration of steroid treatment, r = −0.25 (P = 0.023); cumulative prednisolone equivalent dose, r = −0.07 (P = 0.95); cumulative ribarivin dose, r = 0.07 (P = 0.50). In women, the Spearman correlation coefficients between BMD and the following variables are as follows: duration of steroid treatment, r = 0.014 (P = 0.87); cumulative prednisolone equivalent dose, r = 0.04 (P = 0.64); cumulative ribavirin dose, r = 0.11 (P = 0.19).

Fig. 1.

(a) Scatter diagram showing the BMD for total hip in male SARS patients. (b) Scatter diagram showing the BMD for spine in male SARS patients. (c) Scatter diagram showing the BMD for total hip in female SARS patients. (d) Scatter diagram showing the BMD for spine in female SARS patients.

Table 2.

Z score for the total hip and spine in SARS patients

| Site and age | Men, mean (95% CI) (N) | Women, mean (95% CI) (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Total hip | ||

| 20–49 years | −0.31 (−0.57, −0.05) (65) | 0.02 (−0.19, 0.22) (114) |

| 50 years or above | −0.52 (−1.00, −0.03) (18) | 0.14 (−0.35, 0.64) (27) |

| All | −0.35 (−0.58, −0.13) (83) | 0.04 (−0.15, 0.23) (141) |

| % of subjects with Z score ≤−2 | 6.0%⁎ (5) | 2.8% (4) |

| Total spine | ||

| 20–49 | −0.15 (−0.41, 0.10) (65) | −0.07 (−0.26, 0.18) (114) |

| 50 or above | −0.24 (−0.82, 0.33) (17) | −0.06 (−0.54, 0.42) (27) |

| All | −0.17 (−0.40, 0.06) (82) | −0.07 (−0.24, 0.11) (141) |

| % of subjects with Z score ≤−2 | 3.7% (3) | 0.7% (1) |

P = 0.057 by 1-sided exact binomial test, for the hypothesis that >2.5% of subjects should have a Z score of ≤−2.

The drug regime for patients whose BMD Z score at the hip and spine were −2 or less is shown in Table 3 . It can be seen that only 2 of these patients had relatively low dose prednisolone therapy, while the rest all had intravenous steroid therapy. Most patients also received high doses of ribavirin.

Table 3.

Drug regime for patients whose BMD Z score at the total hip and spine were ≥2

| Patient sex/No. | Total hip Z score | Total spine Z score | Drug treatment protocola | Cumulative prednisolone equivalent dose (mg) | Cumulative ribavirin dose (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/1 | −1.60 | −2.59 | II | 625 | 19,200 |

| M/2 | −2.06 | −2.37 | I | 770 | 32,400 |

| M/3 | −2.09 | −1.77 | IV | 5120 | 36,000 |

| M/4 | −2.18 | −1.33 | III | 2545 | 28,800 |

| M/5 | −2.19 | −0.76 | IV | 8915 | 14,400 |

| M/6 | −2.85 | −2.12 | I | 330 | 24,000 |

| F/1 | −2.05 | −1.77 | IV | 4410 | 3600 |

| F/2 | −2.06 | −1.66 | III | 1885 | 50,400 |

| F/3 | −2.20 | −1.86 | IV | 3010 | 4800 |

| F/4 | −2.43 | −3.20 | II | 3335 | 12,000 |

I: Oral ribavirin as a loading dose of 2.4 g stat followed by 1.2 g three times daily and prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg body weight per day. II: Intravenous ribavirin (400 mg every 8 h) combined with hydrocortisone (100 mg every 8 h). III: Pulses of high-dose methylprednisolone (0.5 g IVI for three consecutive days) added on initial combination therapy. IV: Further pulse of methylprednisolone, up to a total of 3 g.

Discussion

The SARS outbreak was a major public health disaster. In Hong Kong, medical practitioners had to face the challenge of having to treat patients with SARS, even before its origin was known. The use of high-dose steroid and ribavirin therapy was based mainly on anecdotal evidence and its clinical efficacy remains to be proven.

To document the possible detrimental effects of high-dose corticosteroid and ribavirin therapy, the BMD of SARS patients who were thus treated were compared to normal data. We did not find more SARS patients to have hip or spine BMD Z score to be ≤−2 than expected. Although subjects with low BMD had high-dose steroid and ribavirin therapy, and there was a negative association between the duration of steroid therapy and BMD, it cannot be concluded that SARS patients had significantly lower BMD than the normal population.

Contrary to our current results, we have previously found that chronic pulmonary disease (CPD) patients, who were on inhaled steroid therapy, had lower bone mass than normal subjects [4]. Our current results could also be compared to studies conducted in other chest disease patients treated by steroids. In a study by Iqbal [5], the prevalence of osteoporosis was fivefold higher in chronic pulmonary disease (CPD) patients, with the relative risk increasing to 9-fold, if chronic glucocorticoid therapy was used. In a more recent study by Dubois [6], CPD patients on four steroid regimes had their BMD measured. While all these patients had reduced BMD, those who were on intermittent high-dose steroid therapy had the lowest BMD. Finally, in a cohort study, Saito et al. [7] demonstrated that men and women on low-dose oral systemic or inhaled glucocorticoids for a month or more were 2 to 3 times more likely to sustain a vertebral fracture than those in controls.

The result of our study and the above research suggest that while long-term use of steroid may be detrimental to bone, short-term use has a more limited effect. This could be explained by the mechanism of action of glucocorticoid, which takes a long time to be materialized. The inhibition of bone formation is attributable to a shift in the differentiation of mesenchymal cells away from the osteoblastic lineage [8], [9]; and an increase in the death of mature osteoblasts [10]. Moreover, the function of the remaining osteoblasts is diminished, through the inhibition of insulin-like growth factor I expression [11]. Glucocorticoids stimulate osteoclastogenesis and increase the expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor B legend and colony stimulating factor I [12], and decrease the expression of osteoprotegerin [13], [14]. Such in vitro findings were corroborated by the results of a clinical study of BMD and bone turnover in asthmatics receiving inhaled steroids [15], in whom reduced endogenous glucocorticoid and adrenal androgen levels were described.

We conclude that SARS patients who were given short-term but high-dose corticosteroid did not have significantly lower BMD than normal subjects.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the SARS patients who participated in this study, Prof. Henry Lynn for his advice on data analysis and Mr. Jason Leung for performing the data analysis.

References

- 1.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(20):1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlinson B., Cockram C. SARS: experience at Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361:1486–1487. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13218-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau E.M.C., Kwok T., Woo J., Ho S.C. Bone mineral density in Chinese elderly female vegetarians, vegans, lacto-vegetarians and omnivores. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998 (Jan);52(1):60–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau E.M.C., Li M., Woo J., Lai C. Bone mineral density and body composition in patients with airflow obstruction—The role of inhaled steroid therapy, disease and lifestyle. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1998;28:1066–1071. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1998.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iqbal F., Michaelson J., Thaler L., Rubin J., Roman J., Nanes M. Declining bone mass in men with chronic pulmonary disease: contribution of glucocorticoid treatment, body mass index, and gonadal function. Chest. 1999;116:1616–1624. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois E.F., Roder E., Dekhuijen P.N.R., Zwinderman A.E., Schweitzer D.H. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry outcomes in male COPD patients after treatment with different glucocorticoid regiments. Chest. 2002;12:1456–1463. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito J.K., Davis J.W., Wasnich R.D., Ross P.D. User of low-dose glucocorticoids have increased bone loss rates: a longitudinal study. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1995;57:115–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00298431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira R.C., Delany A.M., Canalis E. Effects of cortisol and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on stromal cell differentiation: correlation with CCAAT-enhancer binding protein expression. Bone. 2002;30:685–691. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira R.M.R., Delany A.M., Canalis E. Cortisol inhibits the differentiation and apoptosis of osteoblasts in culture. Bone. 2001;28:484–490. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein R.S., Jilka R.L., Parfitt A.M., Manolagas S.C. Inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and promotion of apoptosis of osteocytes by glucocorticoids. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:274–282. doi: 10.1172/JCI2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canalis E., Centrella M., Burch J., McCarthy T.L. Insulin-like growth factor I mediates selected anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone in bone cultures. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:60–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI113885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suda T., Takahashi N., Udagawa N., Jimi E., Gillespie M.T., Martin T.J. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr. Rev. 1999;20:345–357. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofbauer L.C., Gori F., Riggs B.L. Stimulation of osteoprotegerin ligand and inhibition of osteoprotegerin production by glucocorticoids in human osteoblastic lineage cells: potential paracrine mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4382–4389. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.10.7034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin J., Biskobing D.M., Jadhav L. Dexamethasone promotes expression of membrane-bound macrophage colony-stimulating factor in murine osteoblast-like cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1006–1012. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebeling P.R., Erbas B., Hopper J.L., Wark J.D., Rubinfeld A.R. Bone mineral density and bone turnover in asthmatics treated with long-term inhaled or oral glucocorticoids. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1998;13:1283–1289. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.8.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]