Abstract

The modalities of vascular access for the extracorporeal Artificial Placenta (AP) have undergone many iterations over the past decade. We hypothesized that single lumen jugular cannulation (SLC) using tidal flow ECLS is a feasible alternative to venovenous (VV) umbilical-jugular cannulation and double lumen cannulation (DLC) and can maintain fetal circulation, stable hemodynamics and adequate gas exchange for 24 hours.

After in-vitro evaluation of the tidal flow system, six preterm lambs at EGA 118–124 days (term 145 days) were delivered and underwent VV extracorporeal support. Three were supported using DLC and three with SLC utilizing tidal flow AP support. Hemodynamics, circuit flow and gas exchange were monitored. Target fetal parameters were as follows: mean arterial pressure 40–60mmHg, heart rate 140–240 beats per minute (bpm), SatO2% 60–80%, PaO2 25–50mmHg, PaCO2 30–55mmHg, oxygen delivery >5ccO2/dL/kg/min, and circuit flow 100±25cc/kg/min.

All animals survived 24 hours and maintained fetal circulation with stable hemodynamics and adequate gas exchange. Parameters of the tidal flow group were comparable to those of DLC. Single-lumen jugular cannulation using tidal flow is a promising vascular access strategy for AP support. Successful miniaturization holds great potential for clinical translation to support extremely premature infants.

Keywords: Artificial placenta, extracorporeal life support, prematurity, tidal flow

Introduction

Preterm birth is a significant problem affecting nearly 500,000 births annually in the United States.1 Though the mortality rate from respiratory disease associated with preterm birth has decreased since the Kennedy era and the dawn of exogenous surfactant administration, maternal steroids and advances in ventilation strategies, nearly all neonates <30 weeks estimated gestational age (EGA) and <1,500g will have transient lung disease leading to permanently altered alveolarization, lung development and future lung function.2–4 The highest morbidity and mortality is found in extremely low gestational age newborns (ELGANS) defined as less than 28 weeks EGA.5,6 Due to limited improvement in outcomes in this population with current interventions, a novel approach is needed. The “Artificial Placenta” (AP) is a form of extracorporeal life support (ECLS) that was initially studied nearly 50 years ago.7–9 Its function is to allow a preterm infant to survive outside the womb and continue to develop under fetal conditions. In the past decade, substantial advances have been made in the AP.4,10–12 Clinical translation will require an optimal vascular access strategy.

The modalities of vascular access for the extracorporeal AP have undergone many iterations over the past decade, including two-vessel arteriovenous (AV) cannulation of the umbilical artery and vein,10 venovenous (VV) single lumen cannulation of the jugular and umbilical veins,4,11,12 and single-vessel VV double lumen jugular cannulation (unpublished results). Although a single-vessel double-lumen cannulation (DLC) approach appears feasible for AP applications, clinical translation will require a 5 Fr catheter, which would be too small to deliver adequate flows if configured as a DL catheter. As such, a different perfusion approach using a single lumen cannula with tidal flow appears promising. Tidal flow perfusion, also known in French as AREC (Assistance Respiratoire Extra-Corporelle), was tested in our lab in the 1980s13 and has been used clinically in multiple centers.14–17 We hypothesize that single lumen, single vessel jugular cannulation utilizing a tidal flow AP system is a feasible alternative to the previous two-vessel modes of cannulation and can maintain fetal circulation, stable hemodynamics, and adequate gas exchange for 24 hours.

Methods

To test the tidal flow AP system, we performed two stages of experiments. In the first stage, we tested the single-lumen cannulation system in-vitro to collect data on flow dynamics and tidal volume under various system settings. In the second stage, we tested both the tidal flow and the DLC systems in-vivo in preterm lambs with the aim of maintaining adequate gas exchange, stable hemodynamics, and survival for 24 hours.

Stage 1: In-Vitro Testing

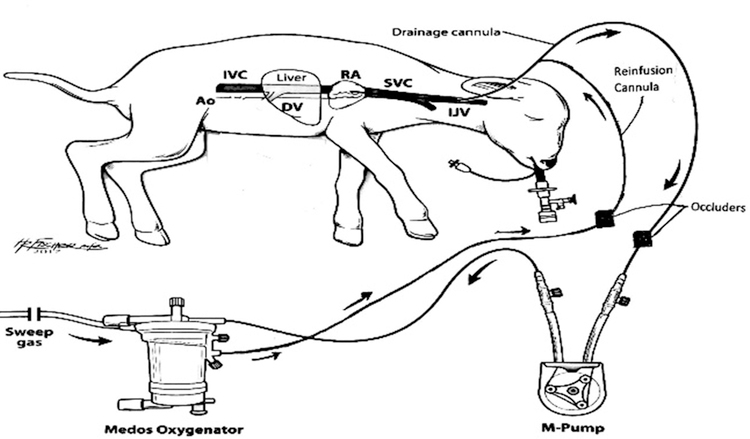

For the in-vitro studies, we constructed a tidal flow circuit made with Saint-Gobain Tygon S3 PVC tubing linking a wire-wrapped single lumen cannula to a 2’’ M-pump (MC3, Ann Arbor, MI) and Medos oxygenator and then returning to the cannula via a Y-connector.18–20 Two occluders were placed on the tubing emerging from either branch of the Y-connector, labeled “Drainage” and “Infusion”. (Figure 1) With the pump running continuously, the occluders were alternatingly engaged allowing for either drainage or infusion of blood into the animal via the cannula, producing a tidal flow effect. The occluders were controlled by a programmable AREC device that was programmed to modulate the duration of drainage and infusion.21

Figure 1:

In-vitro tidal flow ECLS system

We performed in-vitro studies using 5 and 12 Fr cannulae at D:I ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1 and cycle durations of 2,3,4 and 5 seconds using 40% glycerol, which is similar in viscosity to blood. We collected data using a realtime flow totalizer constructed inhouse and SerialPlot data software. The flow totalizer measures both instantaneous flow with 7Hz resolution and a moving average flow over the previous minute. Using MatLab, we plotted the instantaneous flow data and integrated each peak to calculate tidal volume. These values were averaged over one minute to report a standard average tidal volume and effective flow rate for a given setting. We used this in-vitro data to guide the in-vivo stage of experimentation.

Stage 2: In-Vivo Testing

For each of six in-vivo experiments, under a protocol approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), a pregnant ewe was delivered at 118–124d EGA, equivalent to the lung development of a 24- to 26-week EGA human fetus.4,21 Each ewe was placed under general anesthesia for an ex-utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. Monitoring was done via an arterial line placed sterilely in the ewe’s carotid artery and infusions were made through a sterile venous line in the ewe’s jugular vein. A laparotomy was done to expose the uterus. A small hysterotomy was made for the injection of atropine 0.1 mg/kg and buprenorphine 0.01 mg/kg into the fetal lamb. The lamb was partially delivered but remained supported by the ewe’s native placenta. Papaverine was injected into the umbilical vein for vasodilation. A small catheter was inserted in the umbilical vein for sampling and hemodynamic monitoring of the fetus. Lidocaine 1% was injected into the right side of the fetal lamb’s neck subcutaneously. The right jugular vein of the fetus was exposed through an incision in the right neck to prepare for cannulation. In three lambs, a single lumen (10, 12, or 14 Fr) catheter with a Y-connector on the distal end was inserted into the right jugular vein and advanced 10 cm so the tip was placed in the mid-right atrium to serve as both drainage and reinfusion. In the other three lambs, a 15 Fr double lumen cannula was inserted into the right jugular vein and advanced similarly. Placement was confirmed with transthoracic echocardiography.

During this process, the circuit was primed with 240 cc of plasmalyte and subsequently packed red blood cells collected from the ewe. The cannula in the lamb was attached to the fully primed circuit and partial AP support using either continuous or tidal flow, for the respective experiments, was initiated. Once sufficient flow was established and hemodynamics stabilized, the umbilical cord was cut and the fetal lamb was delivered and placed on full AP support using either continuous or tidal flow. For the DLC experiments, flow was delivered and drained continuously via the action of the M-pump, with no additional occlusion mechanism in the circuit. For the tidal flow experiments, flow was drained and reinfused in a pulsatile fashion via the two alternating occluders placed on the drainage and infusion lines of the circuit. These operated according to programmed drainage to infusion times (D:I ratio) and total cycle time for optimal oxygen delivery as described in Stage 1 methods (Figure 2).14 An endotracheal tube (ETT) was placed in all lambs and filled with PFC to a meniscus of 5–10 mmHg pressure. This medium served to simulate the normal prenatal environment, protecting lung development and minimizing electrolyte disturbances.22 Because it was maintained at a set pressure in a closed system, it was not used for gas exchange but did allow simulated fetal breathing movements.

Figure 2:

In-vivo tidal flow schematic

Chronic Care

Postoperative monitoring in all experiments consisted of continuous heart rate, blood pressure, temperature and circuit flow monitoring, including the D:I ratio for the tidal flow, the RPM required to produce the measured flows, the instantaneous flow, and the flows averaged over each minute. Data was recorded every 30 minutes. Each animal was kept in an incubator to maintain a fetal temperature of 38–39°C. Arterial blood gasses were taken every hour to measure glucose, electrolytes, oxygenation and hemoglobin levels. The sweep gas initially consisted of 95% O2/5% CO2 and was titrated throughout the experiment based on PaO2, paCO2 and oxygen saturation measured through the blood gasses. Targeted fetal parameters were as follows: mean arterial pressure 40–60 mmHg, heart rate 140–240 beats per minute (bpm), SatO2% 60–80%, PaO2 25–50 mmHg, PaCO2 30–55 mmHg, oxygen delivery >5 ccO2/dL/kg/min, and circuit flow 100 cc/kg/min.

Maintenance fluids of 0.2% saline with dextrose and necessary electrolytes were continuously administered. Activated clotting time was measured and maintained between 270–350 seconds by modifying the heparin administration. Animals received continuous infusion of prostaglandin E1 (0.2 mcg/kg/min) at 0.2 mcg/kg body weight to maintain patency of the ductus arteriosus and fetal circulation. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) using SMOF (soybean oil, medium chain triglycerides, olive oil and fish oil) was initiated the day of delivery at 25% of maximum feeds and increased incrementally to the goal of full feeds (4 cc/kg/hr) over the course of 24 hours. The ETT pressure was maintained at 5–10 mmHg throughout the experiments with addition of PFC as needed. All animals received piperacillin-tazobactam (100 mg piperacillin/kg every 12 hours), steroids (0.6 mg/kg every 6 hours) and fluconazole (6 mg/kg every day) empirically. Boluses of diazepam (0.1 mg/kg) were given for agitation as needed; buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg every 6 hours) was given empirically for the first 24 hours postoperatively. Necropsy was performed immediately after the death of each animal to assess for gross organ damage and to assess ductal patency.

Results

Stage 1: In-Vitro Results

Mean flow rates and tidal volumes (TV) were observed with 40% glycerol and a baseline M-pump speed of 100 RPM with varied D:I ratios, cannulae, and cycle durations (Table I).

Table I:

In-vitro flow rates and calculated tidal volumes for 5 Fr and 12 Fr catheters

| Cannula size | D:I | Cycle Duration (sec) | Calculated Mean Flow (cc/min) | TV (cc) | Cannula size | D:I | Cycle Duration (sec) | Calculated Mean Flow (cc/min) | TV (cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 French | 3:1 | 5 | 37.37±7.1 | 3.11±0.6 | 12 French | 3:1 | 5 | 333.3±15.95 | 27.8±1.33 |

| 4 | 39.14±9.0 | 2.61±0.6 | 4 | 335.7±21.6 | 22.4±1.4 | ||||

| 3 | 53.37±5.3 | 2.67±0.3 | 3 | 321.0±43.0 | 16.05±2.1 | ||||

| 2 | 120.58±32.7 | 4.02±1.1 | 2 | 242.83±77.9 | 8.09±2.6 | ||||

| 2:1 | 5 | 89.60±12.0 | 7.46±1.0 | 2:1 | 5 | 342.9±12.8 | 28.6±1.1 | ||

| 4 | 95.18±8.8 | 6.35±0.6 | 4 | 350.2±12.8 | 23.3±0.9 | ||||

| 3 | 121.69±15.43 | 6.08±0.8 | 3 | 361.5±17.1 | 18.1±0.9 | ||||

| 2 | 157.87±8.9 | 5.26±0.3 | 2 | 383.3±27.8 | 12.8±1.4 | ||||

| 1:1 | 5 | 56.80±16.4 | 4.73±1.4 | 1:1 | 5 | 367.3±16.0 | 30.6±1.33 | ||

| 4 | 50.35±26.0 | 2.52±1.3 | 4 | 296.35±11.2 | 19.8±0.7 | ||||

| 3 | 33.36±15.16 | 1.67±0.8 | 3 | 303.29±9.1 | 15.16±0.4 | ||||

| 2 | 69.71±15.0 | 2.32±0.5 | 2 | 309.65±15.4 | 10.32±0.5 |

Figure 3 depicts the instantaneous flow rate (orange oscillation) and resulting tidal volumes (blue dots) for the 12 Fr cannula in water at 2:1 D:1, 3 second cycles. This graphing and calculation process was repeated to obtain flow and tidal volume data for all settings with 40% glycerol.

Figure 3:

Sample plot of instantaneous flow and tidal volumes from in-vitro testing

There was some mild turbulence detected with the in-vitro data collection, particularly with the 5 Fr cannula (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Turbulence in ¼ ‘‘ tubing connected to 5-Fr cannula

Stage 2: In-Vivo Results

All lambs survived 24 hours on both tidal flow AP support with a single lumen cannula and DLC AP support. Gas exchange was adequate throughout each experiment in both groups (Figure 5). For the tidal flow experiments, circuit flows averaged 96.98 ± 17.12 cc/min/kg body weight (Figure 6) and average D:I ratios were maintained between 1:1 and 2:1. Mean arterial pressure was maintained above 30 mmHg, with an average of 41.52 ± 9.10 mmHg, and average heart rate was 181 ± 30 bpm (Figure 7). Oxygen delivery (DO2) was 4.54 ± 1.45 ccO2/dL/kg/min and mean pH was 7.23 ± 0.05. For the DLC experiments, circuit flows averaged 102.43 ± 17.46 cc/kg/min (Figure 6), mean arterial pressure was maintained above 30 mmHg, averaging 47.96 ± 6.13 mmHg, and average heartrate was 172.23 ± 25.20 bpm (Figure 7). DO2 was 5.45 ± 0.51 ccO2/dL/kg/min and mean pH was 7.21 ± 0.06. In both groups, there was no evidence of clotting in the circuits. Plasma free hemoglobin was not consistently measured in both groups during the study duration. Upon necropsy, all lambs had pink lung tissue inflated with PFC. Two in the tidal flow group had hepatic congestion, and one had an injury to the right ventricle and thoracic hemorrhage. All animals in both groups had patent DAs.

Figure 5:

Mean gas exchange parameters for DLC and Tidal Flow experiments

Figure 6:

Mean circuit flow for DLC and Tidal Flow experiments

Figure 7:

Mean hemodynamics for DLC and Tidal Flow experiments

Discussion

Despite many advances, prematurity remains an unsolved problem particularly for ELGANs for whom mortality and morbidity have plateaued. An extracorporeal AP is a promising strategy that would revolutionize the treatment of extreme prematurity. Clinical translation will require an optimal vascular access strategy. In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of single-lumen cannulation with tidal flow perfusion to support extremely premature lambs, and miniaturization appears feasible.

Over the past decade, our lab has studied many modes of vascular access for AP support, including venoarterial,10 venovenous,4,11,12 double lumen cannulation (unpublished results), and single-cannula tidal flow systems. Initial studies using pumpless venoarterial support via the umbilical artery and vein were successful for a short duration (4 hours) but failed to provide long-term support due to increasing arterial resistance leading to decreasing device flow.10 As a result, our lab shifted to a pump-driven venovenous extracorporeal life support (VV-ECLS) system. In this model, blood was drained from the right jugular vein (RJV) via the action of an M-pump and was reinfused into the umbilical vein.4 The M-pump allowed for peristaltic flow using a compliant chamber as a passive external reservoir,10 more closely mimicking the compliant physiology of the placenta.10 This minimized risk of negative pressure, cavitation, and tubing rupture under varied patient hemodynamics and drainage rates, and it eliminated issues with high arterial reinfusion pressure. This model successfully supported fetal lambs for one week.9 More recently, we have supported lambs for 2–3 weeks using this model of VV-ECLS. However, with 2–3-week studies, we encountered instances of umbilical vein ulceration and bleeding (unpublished data).

To obviate mechanical problems with the umbilical vein and to simplify vascular access, we hypothesized that single-site double-lumen cannulation of the RJV would provide adequate gas exchange and hemodynamic stability. Our preliminary data suggests the feasibility of using a VV-ECLS approach with a double-lumen catheter (DLC). Although recirculation is a common problem with DLCs,13 this is not a limitation in a fetal model since our optimal oxygen saturations are ~60%. However, a DLC would be unable to deliver sufficient flow if miniaturized to the 5 Fr cannula size required for a preterm human neonate. The internal diameter of each individual lumen would be too small to deliver the 100 ml/kg/min flow rate necessary for sufficient oxygenation.

To effectively miniaturize the vascular access, we shifted our focus to another cannulation and perfusion strategy: single-lumen tidal flow. This system maintains the benefits of a single-site cannulation model which can be miniaturized. Our in-vitro testing has demonstrated that a D:I ratio of 2:1 and total cycle durations of 2–3 seconds yield the greatest flow rates, and thus DO2, for both 5 Fr and 12 Fr cannulae. This finding is corroborated by other in-vitro studies.23,24 Turbulence was noted to increase with decreasing cycle length (increased frequency of direction changes) and with the smaller cannula size. This latter increase is a result of the difference in lumen size between the ¼ inch tubing and the 1.2 mm 5 Fr cannula. The small cannula cannot accommodate the volume pulsed from the tubing, and thus generated turbulence in the tubing that was detected by our flow probe placed on the tubing (Figure 4). We corrected for this phenomenon in our Matlab calculations for tidal volume. Currently, this is the best method to assess flow through the cannula given the circuit structure of the tidal flow system. However, work is being done to allow future studies to incorporate methods of direct measurement of volume passing through the cannula as opposed to the tubing and software to model turbulence for more precise assessment of tidal volumes. A thinner-walled 5 Fr cannula would also aid substantially in reducing turbulence. Another consideration in determining the optimal D:I ratio is reinfusion pressure. While a 3:1 ratio appears to yield sufficient flow (>100 cc/kg/min, Table I), the reinfusion pressures at this flow ratio and higher ratios exceed 300 mmHg, the standard clinical threshold for hemolysis in ECLS.20,25 The danger of hemolysis increases with the smaller 5 Fr cannula as higher pressures are required to deliver adequate flow through the small lumen. Thus, there exists a narrow range of flows that are both adequate and safe for the miniaturized system. Nevertheless, we believe there is an attainable window at D:I ratios less than 3:1 and overall flow rates less than 100cc/min for the miniaturized circuit. Circuit flow, turbulence and reinfusion pressures can be optimized, and hemolysis minimized, at a D:I ratio between 1:1 and 2:1 and cycle durations of 2–3-seconds.23,24,26,27

Our in-vivo studies have demonstrated the feasibility of single lumen tidal flow VV-ECLS to support preterm lambs for 24 hours with stable hemodynamics and adequate gas exchange. The tidal flow system’s optimal D:I range remained consistent with our in-vitro studies and was able to deliver sufficient flow through the 12 Fr cannula while remaining below hemolysis threshold. As such, our results from n=3 are sufficient for proof-of-concept. Acknowledging that these findings are preliminary, the results are promising for future in-vivo studies using the 12 Fr cannula and future miniaturization studies using the 5 Fr cannula.

Tidal flow AP support is not without potential challenges. First, cannulation is highly positional; the tip of the cannula must be placed precisely in the mid-right atrium or the tidal flow will not adequately perfuse the body. Second, the cyclical direction changes introduce turbulence, which increases the theoretical risk for hemolysis. Since plasma free hemoglobin was not consistently measured in this study, we cannot ascertain any differences in hemolysis between groups. Future studies need to incorporate measures of hemolysis. Third, the intermittent occlusion creates sporadic stagnancy on one side of the circuit at any given time, which may promote clotting. Finally, higher pump settings are required to maintain sufficient overall flow and oxygen delivery due to the intermittent reinfusion, and thus the tidal flow model requires a larger M-Pump chamber or the addition of an inflatable bladder into the circuit for higher capacity. These challenges can be surmounted by system changes. The potential for stagnancy and clotting is currently being addressed by a novel nitric oxide-releasing polymer coating of the AP circuit for its anticoagulative properties.28–30 Cycle duration can also be titrated to optimize flow and increase oxygen delivery.

As our work approaches clinical translation, an optimal vascular access strategy is required. Single-lumen cannulation with tidal flow perfusion simplifies vascular access and results in reliable flow with limited recirculation. This mode of AP vascular access can support preterm lambs for 24 hours. It holds great potential to be miniaturized to support extremely premature human neonates. Additional studies with greater sample sizes and in-vivo miniaturized models are needed to further assess and develop this technology.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the students in the University of Michigan Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP) and the ECLS lab volunteers for their contributions to the experiments and chronic care of the animals.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: Project funded by National Institutes of Health – NIH 1R01HD073475-01. No other sources of funding or conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.The Global Toll of Premature Birth. March of Dimes. 2019 Available at https://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/the-global-toll-of-premature-birth.aspx.

- 2.Baraldi E, Filippone M. Chronic lung disease after preterm birth. New Engl J Med 357: 1946–1955, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamath B, MacGuire E, et al. Neonatal mortality from respiratory distress syndrome: lessons for low-resource countries. Pediatrics 127: 6, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryner B, Gray B, Perkins E, et al. An extracorporeal artificial placenta supports extremely premature lambs for one week. J Pediatr Surg 50: 44–49, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray KN, Lorch SA. Hospitalization of early preterm, late preterm, and term infants during the first year of life by gestational age. Hosp Pediatri 3: 194–203, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle EM, Poulsen G, Field DJ, et al. Effects of gestational age at birth on health outcomes at 3 and 5 years of age: Population based cohort study. Brit Med J 344:e896, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawn L, McCance RA. Ventures with an artificial placenta. I. Principles and preliminary results. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 155: 500–509, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zapol WM, Kolobow T, Pierce Jevurek GG, et al. Artificial placenta: two days of total extrauterine support of the isolated premature lamb fetus. Science 166: 617–618, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callaghan JCME, Hug HE. Studies on lambs of the development of an artificial placenta. Can J Surg 8: 208–213, 1965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reoma JL, Rojas A, Kim AC, et al. Development of an artificial placenta I: Pumpless arteriovenous extracorporeal life support in a neonatal sheep model. J Pediatr Surg 44: 53–59, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray BW, El-Sabbagh A, Rojas-Pena A, et al. Development of an artificial placenta IV: 24 hour venovenous extracorporeal life support in premature lambs. ASAIO J 58: 148–54, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray BW, El-Sabbagh A, Zakem SJ, et al. Development of an artificial placenta V: 70h venovenous extracorporeal life support after ventilatory failure in premature lambs. J Pediatr Surg 48: 145–153, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zwischenberger JB, Toomasian JM, Drake K, et al. Total respiratory support with single cannula venovenous ECMO: Double lumen continuous flow vs single lumen tidal flow. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 31: 610–615, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chevalier JY, Couprie C, Larroquet M, et al. Venovenous single lumen cannula extracorporeal lung support in neonates. A five year experience. ASAIO J 39: M654–8, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trittenwein G, Furst G, Golej J, et al. Preoperative ECMO in congenital cyanotic heart disease using the AREC system. Ann Thorac Surg 63: 1298–1302, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chevalier JY, Mathe JC, Costil J, et al. Preliminary report: Extracorporeal lung support for neonatal acute respiratory failure. Lancet 335: 1364–1366, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanchez M, Vazquez J, Blanco D et al. AREC: Primeras experiencias en España. Cir Pediatr 12:113–118, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montoya JP, Merz SI, Bartlett RH. Significant safety advantages gained with improved pressure-regulated blood pump. J Extra Corpor Technol 20: 71–78, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spurlock D, Ranney D, Fracz E, et al. In vitro testing of a novel blood pump designed for temporary extracorporeal support. ASAIO J 58: 109–114, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lequier L, Horton SB, McMullan DM, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuitry. Pediatr Crit Care Med 14: S7–S12, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burri PH. Fetal and postnatal development of the lung. Annu Rev Physiol 46: 617–28, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Church JT, Perkins EM, Coughlin MA, et al. Perfluorocarbons prevent lung injury and promote development during artificial placenta support in extremely premature lambs. Neonatology 113: 313–321, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolobow T, Fumagalli R, Arosio P, et al. The use of extracorporeal membrane lung in the successful resucitation of severely hypoxic and hypercapnic fetal lambs. ASAIO J 28: 365–368, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keszler M, Moront MG, Cox C, et al. Oxygen delivery with a single cannula tidal flow venovenous system for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J 41: 850–854, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi YJ, Huh H, Bae GE, et al. Effect of varying external pneumatic pressure on hemolysis and red blood cell elongation index in fresh and aged blood: Randomized laboratory research. Medicine (Baltimore) 97: e11460, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsen MJ, Orizondo R, Le D, Rojas-Pena A, Bartlett RH. A simple, standard method to characterize pressure/flow performance of vascular access cannulas. ASAIO J 59: 24–29, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montoya JP, Merz SI, Bartlett RH. A standardized system for describing flow/pressure relationships in vascular access devices. ASAIO Trans 37: 4–8, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Major TC, Brisbois EJ, Jones AM, et al. The effect of a polyurethane coating incorporating both a thrombin inhibitor and nitric oxide on hemocompatibility in extracorporeal circulation. Biomaterials 35: 7271–7285, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Annich GM, Miskulin J, et al. Nitric oxide-releasing fumed silica particles: synthesis, characterization, and biomedical application. J Am Chem Soc 125: 5015–5024, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brisbois EJ, Handa H, Major TC. Long-term nitric oxide release and elevated temperature stability with S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP)-doped Elast-eon E2As polymer. Biomaterials 34: 6957–6966, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]