Abstract

Antisense transcription is well known in bacteria. However, translation of antisense RNAs is typically not considered, as the implied overlapping coding at a DNA locus is assumed to be highly improbable. Therefore, such overlapping genes are systematically excluded in prokaryotic genome annotation. Here we report an exceptional 603 bp long open reading frame completely embedded in antisense to the gene of the outer membrane protein ompA. An active σ70 promoter, transcription start site (TSS), Shine-Dalgarno motif and rho-independent terminator were experimentally validated, providing evidence that this open reading frame has all the structural features of a functional gene. Furthermore, ribosomal profiling revealed translation of the mRNA, the protein was detected in Western blots and a pH-dependent phenotype conferred by the protein was shown in competitive overexpression growth experiments of a translationally arrested mutant versus wild type. We designate this novel gene pop (pH-regulated overlapping protein-coding gene), thus adding another example to the growing list of overlapping, protein coding genes in bacteria.

Keywords: overlapping gene, EHEC O157:H7, pH, overexpression phenotypes, protein, ribosomal profiling

Introduction

Due to the nature of the genetic triplet code, six reading frames exist on the two strands of a DNA molecule. Two genes encoded by two different reading frames (ORFs) at the same DNA locus are termed “non-trivially overlapping genes” (OLGs) if the area of sequence overlap is substantial (at least 90 base pairs) and both reading frames encode a protein. Such overlapping genes were discovered in bacteriophage ϕX174 by Barrell et al. as early as 1976 (Barrell et al., 1976). Today, the existence of protein coding OLGs is accepted in viruses, although the evolutionary pressures behind the development of gene overlaps are still debated. Theories about size constraint of the genome in the viral capsid, gene novelty, and evolutionary exploration have been discussed (Chirico et al., 2010; Brandes and Linial, 2016).

In contrast, most overlaps reported in bacterial genomes are very short; the majority being only 1 or 4 bp in same-strand orientation, and we term these trivially overlapping genes. Such very small overlaps seem to increase fitness (e.g., Saha et al., 2016) which might be explained by the translational coupling of expression of the overlapping genes. Due to requiring only a small-scale slippage of the ribosome, mediated by the short overlap, translation is faster and highly efficient in contrast to the conventional translation process which includes dissociation of the ribosome after translation of the upstream gene and time consuming re-association to the downstream ORF of the mRNA (Johnson and Chisholm, 2004).

Very little work has been devoted to the exploration of long overlapping reading frames in prokaryotes, where one ORF is embedded completely in the other ORF (Rogozin et al., 2002; Ellis and Brown, 2003). As bacterial genomes are typically much larger than those of viruses, the original hypothesis suggesting a selection pressure associated with the evolution of overlapping genes in viruses due to an increase of the coding capacity in size-restricted genomes (Normark et al., 1983) has been assumed to be invalid for prokaryotes. In line with this assumption, overlapping genes are systematically excluded in prokaryotic genome annotations (e.g., Warren et al., 2010), which is certainly one reason for the lack of knowledge about such amazing gene constructs in bacteria. Nevertheless, statistical analysis of bacterial genomes has shown that ORFs overlapping annotated genes in alternative reading frames are longer than expected, leading to the hypothesis of a potential selection pressure due to overlapping protein-coding genes (Mir et al., 2012). Besides this, functionality of at least a few non-trivially overlapping genes has been demonstrated (e.g., Behrens et al., 2002; Balabanov et al., 2012).

It is assumed that overlapping genes originated by overprinting of existing, annotated genes (Sabath et al., 2012) and may constitute an evolutionarily young part of the functional genome of bacteria (Fellner et al., 2014, 2015). In contrast to older genes with highly conserved and essential functions, young overlapping genes appear to have weak expression (Donoghue et al., 2011) and their protein functions are suggested to be not essential (Chen et al., 2012). Therefore, the task of functionally characterizing OLGs is challenging. In order to capture weak and condition-specific phenotypic effects caused by the weak expression of non-essential overlapping genes, sensitive methods are necessary (Deutschbauer et al., 2014).

We study non-trivially overlapping genes in the human pathogenic bacterium Escherichia coli O157:H7 (EHEC). Its genome is well characterized, especially with respect to virulence and the associated diseases like enterocolitis, diarrhea, and hemolytic uremic syndrome (Lim et al., 2010; Stevens and Frankel, 2014; Betz et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the coding capacity of EHEC’s genome is likely to be significantly underestimated, both regarding short intergenic genes (Neuhaus et al., 2016; Hücker et al., 2017) and non-trivially overlapping genes (Hücker et al., 2018a, b; Vanderhaeghen et al., 2018). Additionally, using a variety of different next generation sequencing based methods (e.g., RNAseq, Cappable-seq, ribosome profiling) evidence for widespread antisense transcription has accumulated (Conway et al., 2014). In particular, ribosome profiling has been shown to be a powerful technique to investigate the translated part of an organisms’ transcriptome with high precision, through deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments (Ingolia et al., 2009; Hwang and Buskirk, 2016; Nakahigashi et al., 2016). Furthermore, variations of this method were developed to resolve specific features of translation, such as alternative translation initiation sites, translational pausing or translation termination (Woolstenhulme et al., 2015; Baggett et al., 2017; Meydan et al., 2019). Based on such techniques, surprising additional complexity of the bacterial translatome has been uncovered. In particular, findings of putatively translated antisense RNAs could be very significant with respect to overlapping genes (Meydan et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the specificity of the signals found in all NGS experiments needs to be assessed and differentiated from a potentially pervasive background translation, i.e., undirected binding of ribosomes to RNAs (Ingolia et al., 2014). It was reported that pervasive translation initiation sites in bacteria predominantly lead to short translation products with an uncertain functionality status (Smith et al., 2019). However, the metabolic cost of pervasive translation would be high and cells should be driven to minimize such costly side reactions. To gather further evidence for an overlapping coding potential, individual overlapping genes have to be characterized in detail. Such research is in its infancy in bacteria.

Here, we report on a functional analysis of the unusually long, non-trivially overlapping gene pop from E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933, which is fully embedded in antisense to the annotated gene of the outer membrane protein ompA. OmpA is highly conserved among proteobacteria and represents the major outer membrane protein in E. coli with about 100,000 copies per cell (Koebnik et al., 2000). Extensive studies led to the discovery of the β-barrel structure of OmpA (Vogel and Jähnig, 1986) as well as diverse functions of this protein, such as a porin function (Arora et al., 2001) and a local cell wall stabilizing action through interaction of OmpA with TolR (Boags et al., 2019).

Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotides, Bacterial Strains, and Plasmids

All oligonucleotides, bacterial strains and plasmids used or created in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Media, Media Supplements, and Culture Conditions

All E. coli strains were cultivated in LB (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) at 37°C, if not stated otherwise. If necessary, medium was supplemented with additives or stressors (see Supplementary Table S2).

Cloning Techniques

Desired sequences were amplified from genomic DNA of E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 in a PCR [Q5 polymerase, New England Biolabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA, United States] using different primer pairs. PCR fragments were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and ligated in the multiple cloning sites of application specific vectors with T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Vector constructs were transformed in E. coli Top10 cells and plated on LB with required antibiotics. Plasmids were isolated (GenElute Plasmid Miniprep Kit, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) and sequenced with suitable primers (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany) to verify the sequence.

Creation of Translationally Arrested Knock-Out Mutants

The genomic knock-outs E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Δpop and E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Δpop v2 were produced for subsequent competitive growth experiments. The method was adapted from Fellner et al. (2014). Mutation fragments were amplified with primer pairs 1 + 6 and 2 + 5 for the knock-out Δpop. For the knock-out Δpop v2, primer pairs 3 + 7 and 4 + 5 were used. The fragments gained were used in the subsequent overlap extension PCR with primers 5 + 6 or 5 + 7, respectively. The resulting mutation cassettes, Δpop and Δpop v2, were cloned in the plasmid pMRS101 (Sarker and Cornelis, 1997) using ApaI/SpeI and ApaI/XbaI, respectively (selection with ampicillin). The plasmids pMRS101+Δpop and pMRS101+Δpop v2 were isolated and sequenced with primers 7 and 8, respectively. The following steps were performed for both plasmids: A restriction digest with NotI was conducted to remove the high copy ori. The plasmid was re-ligated to the π-protein dependent, low copy plasmid pKNG101+x (x denotes either insert Δpop or Δpop v2), whose maintenance relies either on cells expressing the pir gene, which enables replication, or on integration of the plasmid via homologous recombination – in case the cell does not express the pir gene (Kaniga et al., 1991). Plasmid propagation was performed in E. coli CC118λpir (selection with streptomycin). The conjugation strain E. coli SM10λpir was transformed with pKNG101+x. Overnight cultures (500 μl) of E. coli SM10λpir + pKNG101+x and E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 + pSLTS (selection marker ampicillin, temperature sensitive ori) were mixed and cultivated on LB plates (24 h, 30°C) for conjugation and integration of the plasmid into the genome of EHEC through homologous recombination. Conjugated EHEC cells were transferred on LB/ampicillin/streptomycin plates and selectively cultivated (24 h, 30°C). Correct insertion of the plasmid was confirmed by a PCR using primers 8 + 12 for pKNG101+Δpop or 10 + 12 for pKNG101+Δpop v2. A double-resistant strain was used for loop-out of the mutation plasmid. For this, conjugated EHEC + pSLTS was cultivated in LB at 30°C at 150 rpm until an optical density of OD600 = 0.5 and counter-selected on sucrose agar (modified LB without NaCl supplemented with sucrose) containing 0.02% arabinose to induce the λ red recombination system on pSLTS. Cells with integrated pKNG101+x express the enzyme levansucrase, encoded by the gene sacB, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of sucrose and synthesis of levans. It is proposed that these toxic fructose polymers accumulate in the periplasm of Gram-negative bacteria leading to cell death (Reyrat et al., 1998). Therefore, only sucrose-resistant cells, achieving the second recombination step, have lost the plasmid with its streptomycin resistance. PCR fragments of streptomycin sensitive clones produced with primers 8 + 9 and 10 + 11 for EHEC Δpop and EHEC Δpop v2, respectively, were sequenced to verify integration of the desired mutations into the chromosome. E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Δpop and E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Δpop v2 were cultivated at 37°C to cure the cells from the plasmid pSLTS.

Cloning of pBAD+pop and pBAD+Δpop for Overexpression Phenotyping

For overexpression competitive growth testing, plasmids pBAD+pop and pBAD+Δpop were constructed. For the former construct, primers 14 + 15 were used. The latter construct was created similarly to the mutation cassette described in the previous section (i.e., primers for the mutation fragments are 1 + 14 and 2 + 15; primers for the mutation cassette are 14 + 15). Both PCR fragments, either wild type or mutant, were cloned in the NcoI and PstI sites of pBAD/myc-HisC and plasmids were sequenced with primers 16 + 17. Each of the plasmids was transformed in wild type E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 for subsequent competitive growth assays.

Competitive Growth Assays

For competitive growth, overnight cultures of EHEC transformants containing pBAD+pop or pBAD+Δpop were diluted to OD600 = 1 and mixed in equal amounts. Plasmids were isolated from the bacteria mixture and used as time point zero reference. One hundred microliters of a 1:300 dilution of the initial 1:1 bacteria mixture was used to inoculate 10 ml culture medium with appropriate additives (for working concentration of chemicals see Supplementary Table S2; selection marker ampicillin for plasmid maintenance). Overexpression of pop and Δpop cloned on pBAD was induced with L-arabinose (0.02%) added at the two time points t0 = 0 h and t1 = 6.5 h. Plasmids were isolated after t2 = 22 h and sequenced with primer 16. The competitive index, based on t0 of the mixture pop wild type and pop mutant expressing cells, was calculated. For this, the peak heights (fluorescence signals in Sanger sequencing) of mutated and wild type base at the mutated position were measured. The CI values were calculated according to this formula: CI = (Mtx/Wtx)/(Mtt0/Wtt0) with Wt and Mt the peak heights of wild type and mutant plasmid, respectively, in stress condition or reference condition t0. Mean values and standard deviations of at least three biological replicates were calculated. Significance of a possible growth phenotype was tested with a paired t-test between CI values of the time point t0 reference and the cultured samples (p-value ≤ 0.05).

Competitive growth of wild type EHEC and translationally arrested mutants E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Δpop or E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 Δpop v2 was conducted and evaluated as described above with some exceptions: no selection marker was used; no protein expression was induced; cells were harvested after tx = 18 h; peak heights were determined in t0 and cultured samples by sequencing PCR products amplified from cell lysates with primers 8 + 9 or 10 + 11 for Δpop or Δpop v2 used in competitive growth, respectively (primer for sequencing: 8 or 11).

Copy Number Estimation

Overnight culture of E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 with either pBAD+pop (pop sample) or pBAD+Δpop (Δpop sample) were diluted to OD600 = 1. Diluted cultures (1:300) were used to inoculate 10 ml LB, LB + malic acid or LB + bicine (for working concentration of chemicals see Supplementary Table S2; selection marker ampicillin for plasmid maintenance). Transcripts of pop and Δpop were induced as described for the competitive growth assay. DNA (genomic and plasmid) was isolated after growth of 22 h using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). For this, cultured cells were pelleted and resuspended in 700 μl Tris/EDTA (pH 8) and disrupted with bead beating (0.1 mm zirconia beads) using a FastPrep (three-times at 6.5 ms–1 for 45 s, rest 5 min on ice between the runs). The cell debris was removed after centrifugation (5 min, 16.000 × g, 4°C). Nucleic acids in the supernatant were extracted with 1 Vol phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol twice (vigorously shaking, 5 min, 16.000 × g, 4°C) and precipitated using 2 Vol 100% EtOH and 0.1 Vol 5M NaOAc at −20°C for at least 30 min. After centrifugation (10 min, 16.000 × g, 4°C), the cell pellet was washed twice with 1 ml 70% EtOH (incubation 5 min at room temperature, centrifugation 5 min, 16.000 × g, 4°C). The dried pellet was rehydrated with an appropriate amount of water. RNA was digested using 0.1 Vol of RNase A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DNA was recovered by phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol isolation as before.

Genomic and plasmid DNA was relatively quantified in biological and technical triplicates by qPCR using a genomic specific primer pair amplifying a 105 bp long fragment of the siroheme synthase gene cysG (primer 34 + 35, Zhou et al., 2011) and plasmid specific primers amplifying a 101 bp long fragment of the β-lactamase gene bla (primer 36 + 37, Roschanski et al., 2014). DNA samples were used at a concentration of 100 ng/μl. Amplification cycle differences were calculated for each of the culture conditions [ΔCq(cysG-bla)] for pop and Δpop DNA samples. The ratio of condition specific ΔCq values for pop/Δpop samples was calculated to estimate the deviation of copy numbers in cells overexpressing either of the plasmids. Statistically significant differences of copy number ratios between t0 and each cultured sample was tested for with a paired two sample t-test (p-values ≤ 0.05).

Construction of an Overexpression Plasmid and Western Blot

The plasmid pBAD/myc-HisC, which codes for the peptide tags myc and 6xHis, was modified to obtain the overexpression plasmid pBAD/SPA with the SPA-tag instead (sequential peptide affinity tag, dual epitope tag, consists of calmodulin binding peptide and 3xFLAG-tag separated by a TEV protease cleavage site, Zeghouf et al., 2004). For this, primers 19 + 20 were annealed (heating at 90°C, slow cooling) and completed in a PCR where primers 21 + 22 were added after 5 cycles to amplify the fragment. This PCR product was cloned into pBAD/myc-HisC using SalI and HindIII restriction enzymes. This resulted in an excision of the myc-epitope and in-frame insertion of the SPA-tag. The sequence of pop was cloned next after amplification with primers 14 + 18 in the NcoI and HindIII sites of pBAD/SPA. The plasmid pBAD/SPA+pop was sequenced with primers 16 and 17 for verification and transformed into E. coli O157:H7 EDL933.

Overexpression was performed in LB medium and bicine-buffered LB medium. Cells were cultivated and protein production was induced with 0.002% arabinose when an optical density of OD600 = 0.3 was reached. Cells were harvested right before induction (uninduced control) and at time points 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, and 4 h after induction. The cell volume harvested was adjusted to achieve the same OD600 for all samples regarding uninduced cells (OD600 = 0.3). Whole cell lysates were prepared by adding 50 μl SDS sample buffer (2% SDS, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerin, 0.04% Coomassie blue G250, 200 mM tris/HCl; pH 6.8) and heating at 95°C for 10 min. Proteins in 10 μl of the lysates were separated on a 16% tricine gel prepared according to Schägger (2006), and detected afterward in a Western blot. For this purpose, proteins were blotted semidry (12 V, 20 min) on a PVDF membrane (PSQ membrane, 0.2 μm, Merck Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, United States). After incubating the membrane 5 min in 3% TCA, it was blocked with non-fat dried milk at 4°C. After three washing steps (TBS-T), the membrane was incubated in a 1:1000 dilution of ANTI-FLAG® M2-Alkaline Phosphatase antibody (Sigma Aldrich), which binds the FLAG epitope of SPA-tagged proteins, in TBS-T. SPA tagged proteins were visualized with BCIP/NBT.

Determination of Promoter Activity by a GFP Assay

The promoter sequence of pop was amplified with primers 23 + 24. The product was cloned N-terminally into the promoterless GFP-reporter plasmid pProbe-NT using restriction enzymes SalI and EcoRI resulting in pProbe-NT+promoter-pop. The promoter sequence was verified by sequencing the plasmid with primer 25. The promoter activity was measured in E. coli Top10. For this, 10 ml LB with the appropriate additive (for working concentration of chemicals see Supplementary Table S2; selection marker kanamycin) was inoculated 1:100 with overnight cultures of E. coli Top10, E. coli Top10 + pProbe-NT, and E. coli Top10 + pProbe-NT+promoter-pop and cultivated up to OD600 = 0.6. An appropriate number of cells were harvested, washed once and afterward resuspended in 1xPBS. Fluorescence of 200 μl cell suspension was measured in four technical replicates (Victor3, Perkin Elmer, excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm, measuring time 1 s). Self-fluorescence of cells was subtracted. Mean values and standard deviation of three independent biological replicates were calculated. Statistically significant differences in the fluorescence of promoter construct and empty plasmid or between promoter constructs in different growth conditions were determined using the Welch two sample t-test (p-value ≤ 0.05).

RNA Isolation

RNA was isolated from exponentially grown EHEC cultures (OD600 = 0.3 in LB, LB + L-malic acid, LB + bicine) using Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell pellets were resuspended in 600 μl cooled Trizol and disrupted with bead beating (0.1 mm zirconia beads) using a FastPrep (3-times at 6.5 ms–1 for 45 s, rest 5 min on ice between the runs). Cooled chloroform (120 μl) was added, mixed vigorously and incubated 5 min at room temperature. Phases were separated by centrifugation for 15 min (4°C, 12000 × g) and total RNA in the aqueous upper phase was precipitated with isopropanol, NaOAc and glycogen (690, 27, and 1 μl, respectively) at −20°C for 1 h. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min and washed twice with 80% ethanol. Air-dried RNA was dissolved in an appropriate volume of RNase-free H2O.

DNase Digestion

DNA in RNA samples was digested with Turbo DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction was stopped with 15 mM EDTA and heating for 10 min at 75°C. Digested RNA was precipitated with isopropanol, NaOAc and glycogen (690, 27, and 1 μl, respectively) at −20°C overnight. After centrifugation (20 min, 12000 × g), the pellet was washed once with 80% ethanol. Air-dried RNA was dissolved in an appropriate volume of RNase-free H2O. Successful DNA depletion was verified with a standard PCR using Taq-polymerase (NEB) and primers 26 + 27 binding to the 16S rRNA genes.

cDNA Synthesis and RT-PCR

DNA-depleted total RNA (500 ng) was used for cDNA synthesis with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer using 50 pmol random nonamer primer for 16S rRNA reverse transcription (Sigma Aldrich) or 10 pmol gene specific primers for pop reverse transcription as indicated. SUPERase In RNase Inhibitor (20 U/μl, Invitrogen) was added as well. “No RT” controls contained all components apart from the reverse transcriptase. For RT-PCR, 1 μl of the cDNA sample was used in a standard PCR using Taq-polymerase (NEB) with 20 cycles for product amplification using the primer pairs indicated. Binding of primers was verified in a PCR with genomic DNA as template (not shown).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Relative quantification of pop RNA and 16S rRNA based on cDNA (reverse transcribed with primer 8 and random nonamer primer, respectively) was conducted by qPCR using the SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The reactions contained 12.5 μl master mix, 0.5 μl of forward and reverse primer (50 μM) and 1 μl cDNA at a total volume of 25 μl. Amplification of pop and 16S rRNA was performed with primers 8 + 9 and 26 + 27, respectively. The reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C (5 min, initial denaturation), 40 cycles of denaturation, annealing and elongation at 95°C (15 s), 61°C (30 s), and 72°C (30 s). Finally, a melting curve was acquired for quality control of the amplification products (61°C to 95°C in 0.5°C steps for 5 s). qPCR was performed in three biological replicates in each condition (LB, LB + L-malic acid, and LB + bicine) with three technical replicates for every sample. A no-RT control was included for all samples to verify specificity of the amplification from cDNA (e.g., exclude DNA contamination). pop mRNA was quantified with the ΔΔCq method using 16S rRNA as reference (Pfaffl, 2001). Statistical significance was calculated by means of a one-tailed Welch two sample t-test (p-value ≤ 0.05).

Bioinformatic Analysis

Promoter Determination

The programs BPROM (Solovyev and Salamov, 2011) and bTSSfinder (Shahmuradov et al., 2017) were used to determine the promoter of pop. The input sequence for BPROM was 100 bp long and started 65 bp upstream of the identified TSS. The input for bTSSfinder needed to be longer; it spans 300 bp and starts 197 bp upstream of the TSS. BPROM specifies the promoter strength as a linear discriminant function (LDF) and a sequence with LDF = 0.2 indicates a promoter with 80% accuracy and specificity. bTSSfinder calculates scores based on position weight matrices for different sigma factors and accepts promoters greater than the scoring thresholds (0.06 for σ70).

Terminator Analysis

The program FindTerm (Solovyev and Salamov, 2011) was used to analyze 900 bp downstream of ompA for a rho-independent terminator (threshold −3). The 120 bp long terminator identified was split consecutively into 30 bp segments and all 91 sequences were folded with Mfold (Zuker, 2003) to identify the stem loop structure.

Shine-Dalgarno Sequence Identification

Presence of a Shine-Dalgarno sequence in the region 30 bp upstream of the start codon was analyzed according to Ma et al. (2002). A minimum of ΔG° = −2.9 kcal/mol is required for detection of a ribosome binding site.

Gene Prediction

Genome sequences and assembly data of E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (Accession number CP008957), Shigella dysenteriae str. ATCC 13313 (Accession number CP026774), Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae str. ATCC 13883 (BioProject PRJNA261239), and Enterobacter cloacae subsp. cloacae str. ATCC 13047 (Accession number CP001918) were downloaded from NCBI. Gene prediction was performed with Prodigal v2.60 (Hyatt et al., 2010) with default settings.

Ribosomal Profiling Analysis

Ribosome profiling data of E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 (Neuhaus et al., 2017), samples in LB for two biological replicates, SRR5266618, SRR5266620), E. coli O157:H7 Sakai [Hücker et al. (2017), sample in LB, SRR5874484; files for the two separate biological replicates were kindly provided by Sarah Hücker] and E. coli MG1655 [Wang et al. (2015), samples in LB for two biological replicates; ERR618775, ERR618771] were downloaded from NCBI. Data for E. coli LF82 (GenBank accession: NC_011993) was produced in our lab according to the methods of Hücker et al. (2017) in Schaedler broth medium (anaerobic cultivation). Data evaluation was conducted as following: Adapters were trimmed with cutadapt (Martin, 2011) with a minimum quality score of 10 (q 10) and minimum length of 12 nucleotides (m 12). The trimmed reads were subsequently aligned to the reference chromosome using bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) in local alignment mode, with zero mismatches (N 0) and a seed length of 19 (L 19). Reads overlapping ribosomal and tRNAs were removed using bedtools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Read counts, RPKMs, and coverage were then calculated with respect to the filtered BAM files, using bedtools and a custom bash script.

Stalled-ribosome profiling data from the E. coli strain BL21 was obtained from Meydan et al. (2019). The adapter sequence was predicted using DNApi.py (Tsuji and Weng, 2016), and adapter trimming, alignment, and removal of rRNAs and tRNAs was conducted as described above. The positions of all reads mapped to the forward strand were obtained using SAMtools (Li et al., 2009) and the “bamtobed” tool from BamTools (Barnett et al., 2011). Reads with predicted ribosomal p-sites within 30 nucleotides in each direction of an annotated forward-strand gene start codon (“start region”) were extracted. Weakly expressed annotated genes with no single position (peak) represented by three or more reads, and also with at least four reads situated within the start region, were found using a custom bash script, as a positive control for weak gene expression.

Results

Localization of pop in the Context of the EHEC Genome and Its Expression

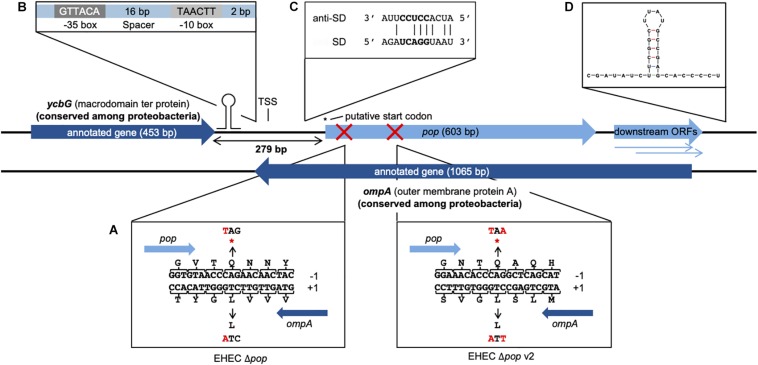

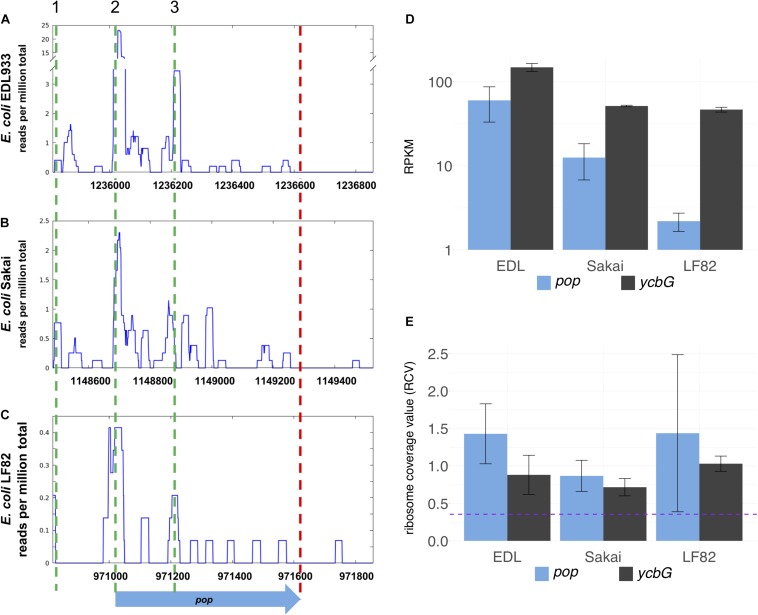

The overlapping gene pop from E. coli O157:H7 (EHEC) EDL933 probably starts at genome position 1236020 (coordinates following the genome annotation of Latif et al. (2014), GenBank accession CP008957) and has a length of 603 bp (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1). It is completely embedded in antisense to the coding sequence of the annotated, highly conserved outer membrane protein gene ompA (1065 bp). pop is located in frame −1 with respect to ompA (Figure 1A). Ribosome profiling of EHEC EDL933 revealed clear evidence of translation of this OLG in LB medium, which is reproducible across biological replicates (Figure 2A and Supplementary Table S3) and EHEC strains (Figures 2A–C, see below). Expression of ompA is about 150 times higher than pop, which is not surprising since OmpA is one of the most highly expressed proteins in E. coli (Ortiz-Suarez et al., 2016). The annotated gene ycbG (453 bp), encoding a macrodomain ter protein, is located upstream of pop. RPKM (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) values of ycbG are on average three times higher than values of pop (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 2D). However, the RPKM of pop in ribosome profiling of EDL933 (i.e., RPKM ≈ 60) is at the same order of magnitude as the median RPKM of all annotated genes with an RPKM of at least 10 (RPKM = 70 and RPKM = 63 for ribosome profiling experiments SRR5266618 and SRR5266620, respectively), supporting genuine expression of pop. In addition to the level of protein expression given by the ribosome profiling RPKM value, the ribosome coverage value (RCV) describes the “translatability” of a particular gene’s messenger RNA, i.e., (Hücker et al., 2017). For pop, the RCV is high, greater than 1 in a few instances. According to Neuhaus et al. (2017), transcripts with an RCV higher than 0.35 can be considered to be translated, while untranslated RNAs have a clearly lower RCV. Therefore, we propose that pop is translated in all pathogenic E. coli strains investigated. Notably, the RCV as measure of the translation of an mRNA into protein is on average higher for pop than for the annotated upstream gene ycbG (Figure 2E and Supplementary Table S3). The finding reinforces our hypothesis that the ribosome profiling signals found for the pop coding region are meaningful and this is clear evidence for translation of pop. Expression of pop was analyzed in three pathogenic E. coli strains (O157:H7 EDL933, O157:H7 Sakai, and LF82) and an E. coli K12 strain (MG1655; Figures 2A–C and Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, pop is translated in EDL933, Sakai, and LF82, with highest values in EDL933, whereas it is neither transcribed nor translated in E. coli MG1655, indicated by low RPKM values and a low RCV.

FIGURE 1.

Genomic organization and operon structure of pop. pop (603 bp) is located downstream of the annotated gene ycbG and completely embedded antisense in the sequence of ompA. Downstream of pop exist two smaller overlapping open reading frames, which overlap ompA almost completely and are referred to as downstream ORFs. A transcription start site (TSS) was experimentally identified in the intergenic region of pop and ycbG. The full genomic sequence of pop is given in Supplementary Figure S1. (A) Design of translationally arrested mutants of pop. The overlapping ORF pop is located in reading frame −1 with respect to ompA. Genomic mutants for phenotypic characterization contained a single base substitution C → T at genome position 1236083 for EHEC Δpop or C → T and G → A at genome positions 1236302 and 1236304 for EHEC Δpop v2 (indicated with red crosses), leading to stop codons (*) in pop and synonymous changes in ompA. (B) Promoter sequence. The sequences of the −10 box and −35 box as well as the length of the spacer between the conserved boxes and the distance to the TSS are shown. (C) Alignment of Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence of pop and anti-Shine-Dalgarno (anti-SD) sequence. The predicted SD sequence (ΔG° = −3.6 kcal/mol) upstream of the putative start codon is aligned to the consensus of the anti-SD sequence of the 16S rRNA in the 30S ribosomal subunit (Ma et al., 2002). The core of the ribosome binding site is displayed in bold letters. (D) Secondary structure of the first 40 bp of the predicted terminator. The folding was conducted with Mfold and the structure has a final energy of ΔG = −8.6 kcal/mol.

FIGURE 2.

Inter-strain comparison of pop translation. Alignment of sequence and ribosomal profiling reads of pop and its homologs across pathogenic E. coli strains O157:H7 EDL933 (A), O157:H7 Sakai (B), and LF82 (C). Graphs show normalized sequencing reads (RPKM, reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) of ribosome profiling experiments in LB medium (A,B) or Schaedler broth (C); the sum signal of two biological replicates is visualized. Three putative start codons are indicated with green dashed lines in region 1 (TTG), 2 (CTG), and 3 (GTG). The stop codon is indicated by a red dashed line. (D) Averaged RPKM values of translation and (E) ribosomal coverage values (RCV) of overlapping gene pop and the upstream annotated gene ycbG of three E. coli strains. Purple dashed line in panel (E): threshold for translated ORFs, RCV = 0.35. Error bars indicate both underlying values used for calculations.

The region between ycbG and pop contains the transcription start site (TSS) and a σ70 promoter (Figure 1B, details further below). Two downstream ORFs, which are arranged in frames −1 and −2 with respect to ompA, are a little over 200 bp long and mostly overlap with ompA (Figure 1). Despite a downstream rho-independent terminator (Figure 1D, details further below) neither of these ORFs appears to be transcribed or translated to a major degree (Supplementary Table S3) and, therefore, we designate the two ORFs in the following simply as downstream ORFs.

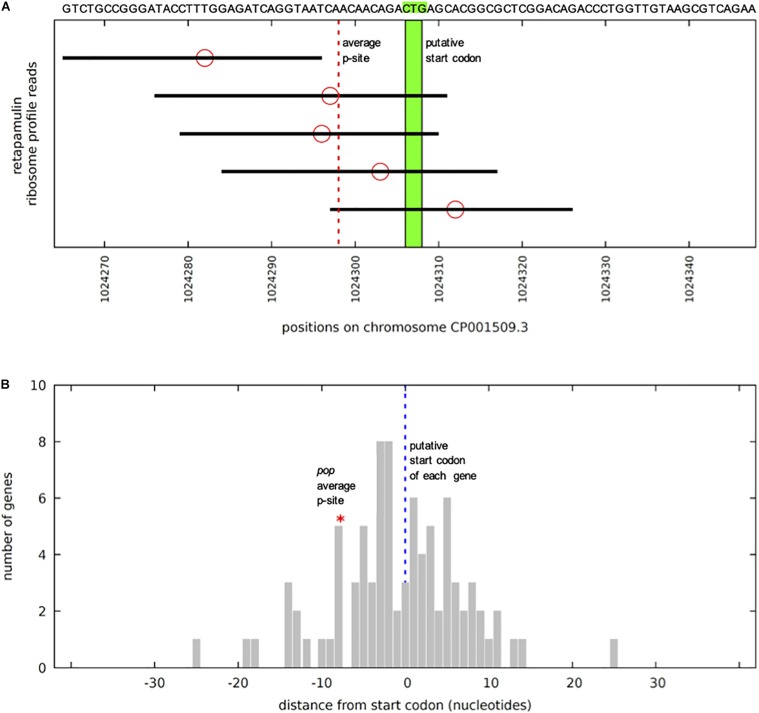

Upstream of the pop-ORF, we detected a Shine-Dalgarno sequence (ΔG° = −3.6 kcal/mol) and the rare start codon CTG nearby (position 1236020, Figure 1C, see also Supplementary Figure S1). Additional evidence for this CTG probably being the translation initiation site is found in recently published stalled-ribosome profiling data using the antibiotic retapamulin in the strain BL21 (Meydan et al., 2019). This antibiotic leads to an arrest of ribosomes starting biosynthesis in the region of translation initiation. Five reads are antisense to ompA, and all of these are clustered in the vicinity of the putative CTG start site of pop (Figure 3A). The read count observed would be unexpected if the cause was a random background translation event. A very conservative calculation of the binomial probability gives P(x ≥ 5) = 0.016 indicating non-random clustering of reads antisense to ompA at the pop start site (Figure 3A). A comparison to weakly expressed annotated genes (selection described in methods section) shows that the putative location of the pop translation initiation site is within the typical range for such genes (Figure 3B), and provides evidence locating the start codon within at most a few nucleotides of the predicted site. Similarly, we find that with pooled ribosome profiling data from EDL933, using the method of Meydan et al. (2019) to predict the ribosomal p-site as described in their methods section precisely identifies the start of the previously mentioned CTG codon (position 1236020) as a translation initiation site.

FIGURE 3.

pop in stalled-ribosome profiling data of E. coli BL21. (A) Reads (black bars) antisense to ompA in the region of pop (sequence indicated above). The five reads situated on the forward strand antisense to ompA are shown, aligned to the BL21 chromosome CP001509.3. Ribosomal p-site locations (red circles) are predicted based on the method of Meydan et al. (2019) – counting 15 nucleotides from the 3′ end of the read. As there is no clear peak, instead the mean of all of the p-sites was calculated. The mean is shown with a dotted red line, pictured in relation to the putative start codon CTG in green. Significance of 5 reads was calculated based on the read distribution modeled as a binomial process. The total sequence space available is 3943267 nucleotides. If we conservatively assume a target size of 100 bp, this equates to a probability of success for a single trial of 100/3943267 = 0.0000254. We find 56812 reads antisense to annotated genes, which is the number of independent trials, if we generously assume as the null hypothesis that all are due to non-functional “background” translation events. With these parameters, the probability of obtaining five or more reads in our target region, i.e., P(x ≥ 5), is equal to 0.0159, therefore 5 reads are significant (p-value ≤ 0.05). (B) Average ribosomal p-site positions for 85 weakly expressed genes. Positions of average p-sites relative to annotated start codons (blue dotted line), as illustrated in panel (A), are plotted for all 85 weakly expressed forward (+) strand annotated gene start regions. Weakly expressed is here defined as having at least four mapped reads within 30 nucleotides of the annotated start site, but no single position (peak) with three or more reads. The location of the average p-site for pop (red asterisk) lies within this distribution, indicating that the observed cluster of ribosome-stalled reads near the CTG site is informative. Thus, we assume that CTG might be the start codon for pop.

In summary, pop was identified as a translated open reading frame based on ribosome profiling experiments. In the following, we present further data supporting a protein-coding status for the gene as well as expression and functionality of this overlapping gene in the human pathogenic bacterium E. coli O157:H7 EDL933.

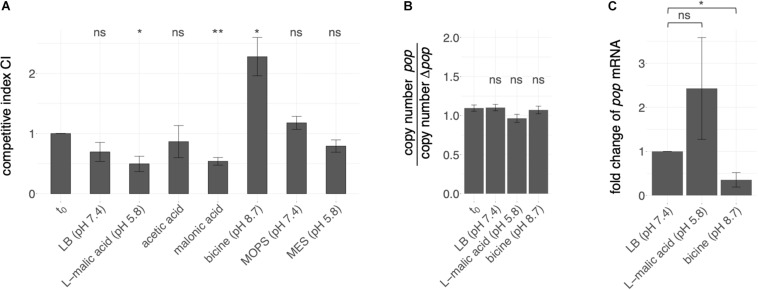

Overexpression Phenotypes Indicate Functionality of pop

Competitive growth experiments were conducted to analyze the influence of pop on EHEC’s growth. For this purpose, the longest possible ORF of pop and the translationally arrested mutant ORF Δpop were cloned in an overexpression plasmid under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter with the optimal ribosome binding site of the plasmid (pBAD+pop and pBAD+Δpop). The mutant plasmid differs in just one base from the wild type plasmid and this single base substitution introduces a stop codon in the overlapping gene (Figure 1A). It is assumed that these small alterations do not change the activity and function of expressed pop RNA possibly working as interfering ncRNA. This would indeed affect ompA RNA levels but for both plasmids equally. However, protein production from the pop gene is ceased in only pBAD+pop. Thus, any difference in growth after overexpression of either the intact or the mutated pop-ORF can be explained by the presence or absence of a protein (i.e., Pop) encoded by this OLG.

The competition experiment was conducted in different stress conditions (Figure 4A). Altered growth of cells overexpressing mutant or wild type sequences was detected in LB-based media supplemented with different stressors, whereas plain LB medium did not have a significant influence on the relative growth of mutant and wild type. For instance, addition of the organic acids L-malic acid and malonic acid as stressors led to better growth of cells containing the wild type plasmid compared to cells expressing the mutated sequence, indicated by a significantly lower CI compared to the t0 condition; thus, the presence of pop is advantageous in these conditions. Addition of the acidic substances resulted in an initial pH shift from 7.4 to 5.8. A higher CI was detected when LB was buffered with bicine to a pH of 8.7. However, LB adjusted to acidic (pH 5.8) or near neutral (pH 7.4) milieu with the biologic buffers MES and MOPS, respectively, did not result in significant growth differences.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of pop expression in various pH ranges. (A) Overexpression phenotypes of pop in competitive growth assays. Competitive growth of EHEC while overexpressing either intact (pBAD+pop) or translationally arrested pop (pBAD+Δpop) was conducted in conditions as indicated, i.e., LB medium supplemented with an organic acid or a biological buffer. Mean competitive indices CI are given as the ratio of relative abundance of cells expressing mutant or wild type plasmid measured by peak heights, i.e., fluorescence intensities in sequencing electropherograms at the mutated positions, in different culture conditions regarding the input ratio t0. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Statistical significant differences of the CI (tested with paired t-test) before and after growth is indicated (* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; ns, not significant). (B) Copy number estimation for both plasmids. Genomic and plasmid DNA of EHEC transformants (pBAD+pop and pBAD+Δpop) separately grown in the indicated growth conditions was relatively quantified by qPCR of a genome section (cysG-gene) and plasmid (bla-gene) specific gene segment. The mean ratios of quantification cycle differences [ΔCq(Cq(cysG)-Cq(bla)) = copy number] for the two transformants of three biological replicates are given. Error bars indicate standard deviations. No statistical significant ratio difference before and after growth was detected (tested with paired t-test; ns, not significant, p-value > 0.05) (C) pop expression measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR). Fold change of pop mRNA has been calculated based on ΔCq (difference in cycles of quantification) values of pop mRNA and 16S rRNA of EHEC grown to early exponential phase (OD600 = 0.3) in LB, LB + L-malic acid or bicine-buffered LB medium. Mean values and standard deviations of three biological replicates are shown. Statistical significance was tested with one-tailed Welch two sample t-test (* p ≤ 0.05; ns, not significant).

We estimated copy number differences of competitors separately grown in LB, LB + L-malic acid and LB + bicine to exclude competitive growth effects occurring due to different plasmid amounts within the cells. In each condition, the cycle threshold differences of the plasmid-encoded gene coding for β-lactamase (bla) and the genome-encoded gene coding for the siroheme synthase (cysG) in cells overexpressing pop or Δpop were determined (ΔCq). The ΔCq ratios of the two competitive strains do not significantly differ before and after growth in any of the conditions (Welch two-sample t-test, p-values > 0.05, Figure 4B and Supplementary Table S4). Thus, growth differences are true effects due to overexpression of pop and Δpop, and not merely copy-number variations of the plasmids.

In accordance with the growth advantage of the wild type in the presence of malic acid (Figure 4A), pop RNA quantification with qPCR showed increased mRNA levels of pop relative to 16S rRNA levels in the presence of L-malic acid (fold change 2.4, Figure 4C and Supplementary Table S5). In contrast, less mRNA was detected in bicine-buffered LB medium at pH 8.7 (fold change 0.35, Figure 4C). Although significantly different Cq values were detected only in the alkaline medium (one-tailed Welch two sample t-test, p-value = 0.03), we suggest that the fold change in L-malic acid also differs, though the p-value is 0.17, as p-values are often combined with a fold change to identify differentially expressed genes (e.g., Huggins et al., 2008; McCarthy and Smyth, 2009). We find that pop expression is differentially regulated between malic acid and bicine based on these qPCR results (fold change 6.9).

Next, genomic knock-outs for pop in E. coli O157:H7 EDL933 were constructed (Δpop and Δpop v2). Base substitutions were introduced 64 and 282 bp downstream of the potential start codon CTG. The stop codon mutation of EHEC Δpop v2 was inserted after the codon GTG in peak region 3 identified in ribosome profiling data (Figures 2A–C, also discussed below). The mutations each led to a stop codon in pop, whereas amino acids in ompA remained unchanged (Figure 1A). We tested the mutant Δpop and Δpop v2 in several relevant stress conditions in competitive growth against the wild type strain, but did not detect a significant difference of growth in any condition for either of the mutants (Supplementary Figure S2).

Based on the clear effect of overexpression, we propose that pop codes for a protein, as mRNAs transcribed from the intact sequence and the translationally arrested variant differ in one nucleotide only. Thus, RNA interactions of pop and ompA are probably not affected. Opposite overexpression phenotypes were found in alkaline buffered and acidified media, so we propose a pH-dependent function. In line with this hypothesis, the mRNA is differentially regulated in various pH conditions (Figure 4C).

The Transcriptional Unit of pop Includes an Active Promoter and a Rho-Independent Terminator

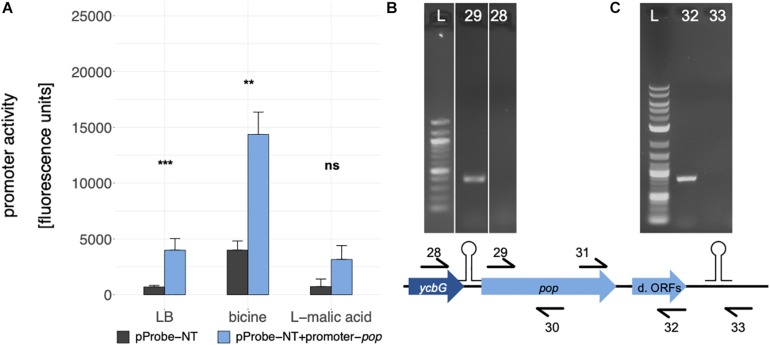

Cappable-seq (Ettwiller et al., 2016) is a recently developed approach detecting the TSS of mRNA with next generation sequencing. Using this method, a weak but significant transcriptional start site was determined at genome position 1235862 in the intergenic region between ycbG and pop in independent biological experiments (Figure 1, TSS; Supplementary Figure S1). Two independent bioinformatics tools, BPROM and bTSSfinder, were used to analyze the upstream region of the TSS for potential promoter sequences. Both programs identified a σ70 promoter [BPROM LDF score 0.59, Solovyev and Salamov (2011), bTSSfinder score 1.86, Shahmuradov et al. (2017), Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1]. Although the distance between the transcriptional start site and −10 box of the promoter is not optimal (2 bp instead of approx. 7 bp), promoter sequence activity was verified by means of a GFP-assay (Figure 5A). We found a significantly enhanced fluorescence in cells harboring the plasmid containing the putative promoter sequence compared to those with the empty vector in LB and bicine-buffered medium, indicating an active promoter sequence upstream of the TSS of pop. The fluorescence signal of the promoter in the basic milieu (pH 8.7) was strikingly higher, but this may result from GFP accumulation during longer incubation times necessary in this medium (Miller et al., 2000).

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of the pop transcriptional unit. (A) Promoter activity assay for the promoter of pop, which was introduced in the promoterless GFP vector pProbe-NT. Mean fluorescence units of E. coli Top10 cells with the different constructs in culture conditions as indicated are given. Error bars show standard deviations. Statistical significance between empty vector (gray bars) and the promoter construct (blue bars) was tested with a Welch two sample t-test (** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant). (B) Test for mono- or polycistronic mRNA. An agarose gel of RT-PCRs is shown. RNA was reverse transcribed in cDNA with pop specific reverse primer 30. Two different forward primers, binding within ycbG (no. 28) or within pop (no. 29), were combined with a pop reverse primer (no. 30). L: 100 bp DNA Ladder (NEB); 28: PCR with primers 28 + 30; 29: PCR with primers 29 + 30. (C) Test for the predicted rho-independent terminator. An agarose gel of RT-PCRs is shown. RNA was reverse transcribed in cDNA with pop specific reverse primers 32 or 33 binding upstream (no. 32) or downstream (no. 33) of the stem loop structure. For PCR, these two reverse primers were combined with a pop forward primer (no. 31). L, 1 kb plus DNA Ladder (NEB); 32: PCR with primers 32 + 31; 33: PCR with primers 33 + 31; d. ORFs, downstream ORFs.

Since the promoter activity for pop is weak compared to promoters of annotated genes, we tested for polycistronic expression starting from the promoter of ycbG. Reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) was performed to examine the transcript of pop (Figure 5B). No mRNA spanning both genes was detectable, thus, we propose that pop is transcribed from the tested promoter monocistronically.

A 120 bp long rho-independent terminator was predicted 295 bp downstream of the stop codon of pop using FindTerm (Solovyev and Salamov, 2011). Hypothetical secondary structures of 30-bp segments of this region were created with the tool Quickfold of Mfold (Zuker, 2003). A stable stem loop structure (ΔG = −8.6 kcal/mol) within bases 35–78 of the predicted terminator sequence was detected (Figure 1D). To verify the 3′-end of the mRNA downstream of the hairpin structure, RT-PCRs were performed. We used reverse primers binding either within the downstream ORFs or further downstream, beyond the secondary structure. We observed that pop and the downstream ORFs are co-transcribed and transcription is terminated just downstream of the predicted stem loop structure (Figure 5C).

Based on these results, we conclude that pop forms an approximately 1120 bp long transcriptional unit covering almost the entire open reading frame of the annotated gene ompA, excluding the upstream gene ycbG but including the downstream ORFs, ending with a rho-independent terminator.

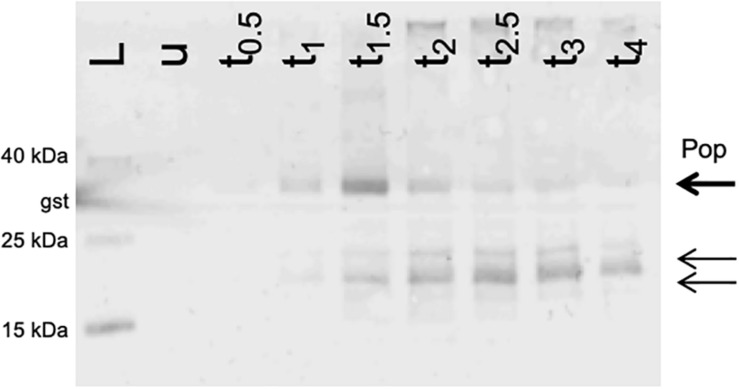

Western Blot of Pop

Since we detected an active promoter (Figure 5A) and phenotypes in competitive overexpression experiments (Figure 4A), the coding capacity of pop was assessed using Western blotting. pop was cloned in-frame with an SPA tag (7.7 kDa; following Zuker, 2003) on a pBAD-based plasmid, and overexpressed in EHEC. SPA-tagged proteins were visualized after separating whole cell lysates on tricine gels. The experiment was performed in LB at pH 7.4 (Figure 6). Besides the expected full-length protein (theoretically 30 kDa, detected approx. 34 kDa), shorter products were immunostained (approx. 20 and 24 kDa). The amount of the full Pop protein appears to increase within the first 1.5 h after induction and decreases afterward when overexpressed, pointing to an instability of the protein. However, this experiment does not prove natural occurrence of the protein, due to artificial overexpression of the protein. On the other hand, detection of an endogenously expressed protein in Western blots failed as pop-tagged cells could not be recovered due to technical issues. Nevertheless, we could detect an initially stable Pop protein, supporting a protein coding potential of pop in general.

FIGURE 6.

Western blot of Pop protein. Expression of pop in frame with a C-terminal SPA-tag. Cells were grown in LB at pH 7.4 and harvested before induction and up to 4 h after induction (tx) and normalized cell numbers were separated on 16% tricine gels. The arrows indicate the band of the putative full-length protein Pop (bold arrow) and two shorter products (thin arrows). The experiment was conducted in LB at pH 7.4. L, Spectra Multicolor Low Range Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific) with additional internal Western blot control glutathione-S-transferase (band sizes are indicated); u, whole cell extract from uninduced cells; tx, whole cell extract from samples harvested after x = 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, and 4 h after induction with arabinose.

Bioinformatic Evidence for pop Being a Protein-Coding Gene

Protein databases were searched for Pop homologs in order to find hints of a specific function. No significant similarities with annotated proteins were found using blastp analysis in PDB (Protein Data Bank), UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot and the Ref-Seq protein database, but homologous proteins were detected in NCBI’s non-redundant protein sequence (nr) database. However, the hits covered at best 67% of the amino acid sequence of pop. A deeper analysis of the top hit (uncharacterized protein, 67% coverage, 99% identity, e-value of 4–91) and the genomic sequence of the target organism Shigella sonnei showed that its ompA homolog was not annotated due to ambiguous bases at its 5′ end, which resulted in a missing start codon for ompA in this case. Consequently, pop was “allowed” to be predicted ab initio, as ompA had no obvious gene structure and was, therefore, rejected during annotation. This result corroborates the known function of many algorithms like Glimmer, Prodigal or Prokka, which systematically avoid annotation of long (non-trivially) overlapping genes (Delcher et al., 2007; Hyatt et al., 2010; Seemann, 2014). Further, NCBI explicitly forbids long overlaps in their prokaryote genome annotation standards (NCBI, 2018). To check whether pop is recognized by gene finding algorithms in the case of an absent ompA annotation, we applied Prodigal to four genomes of bacteria in the family Enterobacteriaceae (E. coli O157:H7 EDL933, S. dysenteriae, K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae). Potential start codons of ompA were masked with N bases in each genome and consequently ompA was not detected. In contrast, pop was predicted as a protein-coding gene in all four genomes (Supplementary Table S6). The absolute prediction scores of all annotated protein-coding genes in this analysis ranged from −0.5 to >1000 in EHEC. The total score of pop is 14.37 and falls within the lowest 10% of the 5351 predicted EHEC coding sequences. Nevertheless, sequences with even lower scores than pop represent conserved annotated genes, e.g., a fimbrial chaperon or the entericidin A protein, to name two of many. Thus, pop has elements of a gene structure which enable its identification as a protein-coding gene when ompA is masked. In the normal case, pop is apparently rejected in annotation solely due to its overlapping gene partner ompA rather than any property of the sequence itself.

Discussion

Antisense transcription is a widespread phenomenon in bacteria and often connected to regulatory function of the RNAs (Dornenburg et al., 2010; Ettwiller et al., 2016). However, there is increasing evidence that antisense RNAs can be templates for ribosomes to synthesize proteins (Miranda-CasoLuengo et al., 2016; Weaver et al., 2019). So far, characterized non-trivially overlapping genes are typically short (e.g., Fellner et al., 2014; Haycocks and Grainger, 2016; Hücker et al., 2018a). Therefore, the discovery and analysis of pop with a length of 200 amino acids is of special interest.

The number of coding sequences in bacteria predicted by genome annotation algorithms is underestimated, in particular because neither small genes nor genes with extensive overlap are considered to be true genes (Burge and Karlin, 1998; Delcher et al., 2007; Hücker et al., 2017). Therefore, it is not surprising that pop has until now escaped attention. In our study, we detected translation of pop in three pathogenic E. coli strains. Although whether ribosome-profiling signals indicate translation of genes in all cases is debated, independent confirmation of expression or function for specific genes can be achieved either by chromosomal tagging (e.g., Baek et al., 2017; Meydan et al., 2019) or functional characterization, as for example presented here using competitive growth. The pattern of translation in ribosome-profiling data of this ORF is conserved across widely divergent E. coli strains, albeit with very low translation in some strains. It has been shown that translation of even short proteins in E. coli is associated with a significant bioenergetic cost (Lynch and Marinov, 2015), and specific translation of non-functional genes would therefore be expected to be acted against by selective processes relatively quickly. The strains compared diverged more than 4 million years ago according to molecular clock methods in the case of K12 and Sakai (Reid et al., 2000). This corresponds to more than 1 billion generations, and LF82 is still more distantly related. Consequently, we would expect all non-functional translated products shared with the common ancestor of these strains to have been lost. In contrast to conserved translation in pathogenic E. coli, pop translation was not observed in the well-studied E. coli K12. This finding, in combination with the discarding of pop in automated annotation, as it is embedded antisense in the conserved outer membrane protein ompA, leads us to propose that it was simply overlooked so far.

We studied the transcriptional unit of pop and identified (i) a TSS (ii) downstream of a σ70 promoter, (iii) a potentially coding ORF (i.e., pop) with a putative CTG start codon, and (iv) an experimentally verified rho-independent terminator of pop.

In the ribosome profiling data, we identified three peak regions, which are evidence for translation initiation sites in translatome data (Oh et al., 2011; Woolstenhulme et al., 2015); a putative start codon of pop could be contained in each of these (regions 1–3 in Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S1). All regions are covered with a substantial number of ribosomal profiling reads, and region 2 is covered best, particularly in EHEC EDL933. We assume that translation for pop starts in region 2, especially since a Shine-Dalgarno motif for ribosome binding was predicted and ribosome profiling data across divergent strains point to a putative translation initiation site therein. As mentioned, a nearby CTG is found downstream of a ribosome-binding site, representing a rare but sometimes-used start codon for prokaryotes (Spiers and Bergquist, 1992; Sussman et al., 1996; Hecht et al., 2017; Yamamoto et al., 2018).

Furthermore, a TTG start codon is present in region 1, representing the longest potential ORF for pop. However, we could not find evidence for a TSS or SD-sequence, though the latter is not obligatory for gene expression (Moll et al., 2002; Gualerzi and Pon, 2015). This TTG was the start codon predicted by Prodigal as the most probable one, however, as the upstream gene ycbG has a predicted terminator (ΔG = −12.20 kcal/mol, indicated in Figures 1, 5B) and bicistronic expression of pop along with ycbG was excluded by our data, we propose that this TTG is not a start codon here.

The start codon in region 3 (GTG) is located 45 amino acids downstream of the mutation introduced in pop for analysis in competitive growth. We did not find a phenotype for a translationally arrested mutant regarding this putative start codon. Furthermore, overexpression growth phenotypes found in competitive growth experiments are not conferred by the protein translated from this start codon. While these points are strong evidence that this GTG is not the start codon, formation of a protein isoform not carrying a phenotype in the conditions analyzed here cannot be excluded.

In addition to the gene structure, the Pop protein was analyzed in our study. A Western blot verified the presence of a protein, which appears to be unstable when expressed from the plasmid. Nevertheless, native protein expression could not be investigated immunologically and natural occurrence of the protein Pop remains unclear. Pop might be stable, degraded or exist in different isoforms, a phenomenon reported for some bacterial proteins recently (Waters et al., 2011; Di Martino et al., 2016; Nakahigashi et al., 2016; Vanderhaeghen et al., 2018; Meydan et al., 2019).

Most importantly, competitive overexpression growth assays conducted in this study are the best indication for a proteinaceous nature of the pop gene product. As recently shown, not only loss-of-function screenings but also overexpression phenotyping is an appropriate approach to find novel genes and to elucidate their function (Mutalik et al., 2019). However, as shown previously, overexpression of unnecessary but usually non-toxic proteins often leads to decreased growth rates (Dong et al., 1995; Shachrai et al., 2010). This could be assumed in our assay conducted in bicine-buffered LB, in which cells expressing the full-length protein had significantly lower growth. Nevertheless, as growth behaviors of mutant and wild type pop expressing cells did not change in pure LB, the phenotype seems to be rather specific for the alkaline stress conditions and not due to an effect of overexpression stress. However, in acidified medium the cells had a growth advantage in comparison to cells expressing the truncated form and, thus, pop overexpression is beneficial to EHEC at low pH. This is important since this effect cannot be explained by stressed cells due to protein overexpression. In contrast, analysis of a genomic knock-out suggests that the absence of the protein is not deleterious for EHEC under the conditions tested. While it has been shown that effects of overexpression and knock-out can be complementary, this is not always the case (Prelich, 2012). Several examples exist in which the actions of genes can be compensated by each other [e.g., CLN1 and CLN2 in S. cerevisiae, Hadwiger et al. (1989); cold shock proteins in bacteria, Xia et al. (2001)]. For CLN1 and CLN2, both have similar effects when overexpressed separately, but absence of one of the genes can be balanced out by the other and only a double knock-out has a phenotype.

In summary, we suggest that the investigated open reading frame encodes a protein, since it has all structural features of a protein coding gene, is translated and it shows overexpression phenotypes in pH stress. We propose the name pop (pH-regulated overlapping protein-coding gene) for this novel overlapping gene. It should be noted that the hemC/F/H/L genes were previously referred to as popA/B/C/E but the OLG pop is not associated with any function of these. It could be speculated that the positive effect of overexpressed pop in acidic medium correlates with the acid tolerance of EHEC necessary to overcome the acidic barrier in the stomach after ingestion (Nguyen and Sperandio, 2012). If true, pop could be a pathogenicity or host-environment related gene of EHEC only activated upon specific stress.

Long ORFs embedded antisense to annotated genes like pop, as well as other overlapping ORFs, may form a hitherto greatly underestimated source of proteins. Recently developed methods like dRNA-seq (Sharma et al., 2010) and Cappable-seq (Ettwiller et al., 2016) identified hundreds of TSSs antisense to annotated genes producing antisense transcripts with unknown translation status and function. Modern ribosome profiling techniques, including stalling ribosomes at translation initiation sites, identified several unambiguous start codons for protein coding genes, which overlap with annotated genes either in sense or in antisense direction (Meydan et al., 2019; Weaver et al., 2019). We suggest that these “abnormal” transcriptional and translational signals in next generation sequencing analysis should not be neglected but analyzed in more detail, as has been conducted for the long overlapping gene pop. Many novel functional elements, especially for pathogenicity in novel hosts or survival in new niches, might be “hiding” in the genome of any bacterium.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for E. coli LF82 can be found in the Sequence read archive; accession numbers are SRR11217090, SRR11217089, SRR11217088, and SRR11217087.

Author Contributions

BZ performed the experimental analysis on pop in EHEC EDL933 and database searches. ZA conducted the analysis of ribosomal profiling data. MK performed the ribosomal profiling in LF82. SS and KN supervised the study. BZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript including the figures with the help of KN and SS. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Romy Wecko for excellent technical assistance and Christopher Huptas for his support in gene prediction. We thank Sarah Hücker for providing ribosomal profiling data for the two biological replicates of E. coli O157:H7 Sakai.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to SS (SCHE316/3-1,2,3).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00377/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arora A., Abildgaard F., Bushweller J. H., Tamm L. K. (2001). Structure of outer membrane protein a transmembrane domain by NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. Evol. 8 334–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek J., Lee J., Yoon K., Lee H. (2017). Identification of unannotated small genes in Salmonella. G3 7 983–989. 10.1534/g3.116.036939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett N. E., Zhang Y., Gross C. A. (2017). Global analysis of translation termination in E. coli. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006676. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanov V. P., Kotova V. Y., Kholodii G. Y., Mindlin S. Z., Zavilgelsky G. B. (2012). A novel gene, ardD, determines antirestriction activity of the non-conjugative transposon Tn5053 and is located antisense within the tniA gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 337 55–60. 10.1111/1574-6968.12005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D. W., Garrison E. K., Quinlan A. R., Strömberg M. P., Marth G. T. (2011). BamTools: a C++ API and toolkit for analyzing and managing BAM files. Bioinformatics 27 1691–1692. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrell B. G., Air G., Hutchison C., III (1976). Overlapping genes in bacteriophage φX174. Nature 264 34–41. 10.1038/264034a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens M., Sheikh J., Nataro J. P. (2002). Regulation of the overlapping pic/set locus in Shigella flexneri and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 70 2915–2925. 10.1128/iai.70.6.2915-2925.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz J., Dorn I., Kouzel I. U., Bauwens A., Meisen I., Kemper B., et al. (2016). Shiga toxin of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli directly injures developing human erythrocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 18 1339–1348. 10.1111/cmi.12592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boags A. T., Samsudin F., Khalid S. (2019). Binding from both sides: TolR and full-length OmpA bind and maintain the local structure of the E. coli cell wall. Structure 27 713–724.e2. 10.1016/j.str.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes N., Linial M. (2016). Gene overlapping and size constraints in the viral world. Biol. Direct 11:26. 10.1186/s13062-016-0128-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge C. B., Karlin S. (1998). Finding the genes in genomic DNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8 346–354. 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.-H., Trachana K., Lercher M. J., Bork P. (2012). Younger genes are less likely to be essential than older genes, and duplicates are less likely to be essential than singletons of the same age. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29 1703–1706. 10.1093/molbev/mss014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico N., Vianelli A., Belshaw R. (2010). Why genes overlap in viruses. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 277 3809–3817. 10.1098/rspb.2010.1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway T., Creecy J. P., Maddox S. M., Grissom J. E., Conkle T. L., Shadid T. M., et al. (2014). Unprecedented high-resolution view of bacterial operon architecture revealed by RNA sequencing. mBio 5:e01442-14. 10.1128/mBio.01442-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher A. L., Bratke K. A., Powers E. C., Salzberg S. L. (2007). Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 23 673–679. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschbauer A., Price M. N., Wetmore K. M., Tarjan D. R., Xu Z., Shao W., et al. (2014). Towards an informative mutant phenotype for every bacterial gene. J. Bacteriol. 196 3643–3655. 10.1128/JB.01836-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino M. L., Romilly C., Wagner E. G. H., Colonna B., Prosseda G. (2016). One gene and two proteins: a leaderless mRNA supports the translation of a shorter form of the Shigella VirF regulator. mBio 7:e01860-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Nilsson L., Kurland C. G. (1995). Gratuitous overexpression of genes in Escherichia coli leads to growth inhibition and ribosome destruction. J. Bacteriol. 177 1497–1504. 10.1128/jb.177.6.1497-1504.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue M. T., Keshavaiah C., Swamidatta S. H., Spillane C. (2011). Evolutionary origins of Brassicaceae specific genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Evol. Biol. 11:47. 10.1186/1471-2148-11-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornenburg J. E., Devita A. M., Palumbo M. J., Wade J. T. (2010). Widespread antisense transcription in Escherichia coli. mBio 1:e00024-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J. C., Brown J. W. (2003). Genes within genes within bacteria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28 521–523. 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettwiller L., Buswell J., Yigit E., Schildkraut I. (2016). A novel enrichment strategy reveals unprecedented number of novel transcription start sites at single base resolution in a model prokaryote and the gut microbiome. BMC Genomics 17:199. 10.1186/s12864-016-2539-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellner L., Bechtel N., Witting M. A., Simon S., Schmitt-Kopplin P., Keim D., et al. (2014). Phenotype of htgA (mbiA), a recently evolved orphan gene of Escherichia coli and Shigella, completely overlapping in antisense to yaaW. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 350 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellner L., Simon S., Scherling C., Witting M., Schober S., Polte C., et al. (2015). Evidence for the recent origin of a bacterial protein-coding, overlapping orphan gene by evolutionary overprinting. BMC Evol. Biol. 15:283. 10.1186/s12862-015-0558-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualerzi C. O., Pon C. L. (2015). Initiation of mRNA translation in bacteria: structural and dynamic aspects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72 4341–4367. 10.1007/s00018-015-2010-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwiger J. A., Wittenberg C., Richardson H. E., De Barros Lopes M., Reed S. I. (1989). A family of cyclin homologs that control the G1 phase in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 6255–6259. 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycocks J. R., Grainger D. C. (2016). Unusually situated binding sites for bacterial transcription factors can have hidden functionality. PLoS One 11:e0157016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht A., Glasgow J., Jaschke P. R., Bawazer L. A., Munson M. S., Cochran J. R., et al. (2017). Measurements of translation initiation from all 64 codons in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 3615–3626. 10.1093/nar/gkx070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hücker S. M., Ardern Z., Goldberg T., Schafferhans A., Bernhofer M., Vestergaard G., et al. (2017). Discovery of numerous novel small genes in the intergenic regions of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai genome. PLoS One 12:e0184119. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hücker S. M., Vanderhaeghen S., Abellan-Schneyder I., Scherer S., Neuhaus K. (2018a). The novel anaerobiosis-responsive overlapping gene ano is overlapping antisense to the annotated gene Ecs2385 of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai. Front. Microbiol. 9:931 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hücker S. M., Vanderhaeghen S., Abellan-Schneyder I., Wecko R., Simon S., Scherer S., et al. (2018b). A novel short L-arginine responsive protein-coding gene (laoB) antiparallel overlapping to a CadC-like transcriptional regulator in Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai originated by overprinting. BMC Evol. Biol. 18:21. 10.1186/s12862-018-1134-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins C., Domenighetti A., Ritchie M., Khalil N., Favaloro J., Proietto J., et al. (2008). Functional and metabolic remodelling in Glut4-deficient hearts confers hyper-responsiveness to substrate intervention. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 44 270–280. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J.-Y., Buskirk A. R. (2016). A ribosome profiling study of mRNA cleavage by the endonuclease RelE. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 327–336. 10.1093/nar/gkw944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D., Chen G.-L., Locascio P. F., Land M. L., Larimer F. W., Hauser L. J. (2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11:119. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia N. T., Brar G. A., Stern-Ginossar N., Harris M. S., Talhouarne G. J., Jackson S. E., et al. (2014). Ribosome profiling reveals pervasive translation outside of annotated protein-coding genes. Cell Rep. 8 1365–1379. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia N. T., Ghaemmaghami S., Newman J. R., Weissman J. S. (2009). Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science 324 218–223. 10.1126/science.1168978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Z. I., Chisholm S. W. (2004). Properties of overlapping genes are conserved across microbial genomes. Genome Res. 14 2268–2272. 10.1101/gr.2433104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniga K., Delor I., Cornelis G. R. (1991). A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109 137–141. 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koebnik R., Locher K. P., Van Gelder P. (2000). Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol. Microbiol. 37 239–253. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01983.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9 357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif H., Li H. J., Charusanti P., Palsson B. Ø., Aziz R. K. (2014). A gapless, unambiguous genome sequence of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933. Genome Announc. 2:e00821-14. 10.1128/genomeA.00821-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., et al. (2009). The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J. Y., Yoon J. W., Hovde C. J. (2010). A brief overview of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its plasmid O157. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20 5–14. 10.4014/jmb.0908.08007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Marinov G. K. (2015). The bioenergetic costs of a gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 15690–15695. 10.1073/pnas.1514974112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Campbell A., Karlin S. (2002). Correlations between Shine-Dalgarno sequences and gene features such as predicted expression levels and operon structures. J. Bacteriol. 184 5733–5745. 10.1128/jb.184.20.5733-5745.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D. J., Smyth G. K. (2009). Testing significance relative to a fold-change threshold is a TREAT. Bioinformatics 25 765–771. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meydan S., Marks J., Klepacki D., Sharma V., Baranov P. V., Firth A. E., et al. (2019). Retapamulin-assisted ribosome profiling reveals the alternative bacterial proteome. Mol. Cell 74 481–493.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. G., Leveau J. H., Lindow S. E. (2000). Improved gfp and inaZ broad-host-range promoter-probe vectors. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13 1243–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir K., Neuhaus K., Scherer S., Bossert M., Schober S. (2012). Predicting statistical properties of open reading frames in bacterial genomes. PLoS One 7:e45103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-CasoLuengo A. A., Staunton P. M., Dinan A. M., Lohan A. J., Loftus B. J. (2016). Functional characterization of the Mycobacterium abscessus genome coupled with condition specific transcriptomics reveals conserved molecular strategies for host adaptation and persistence. BMC Genomics 17:553. 10.1186/s12864-016-2868-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll I., Grill S., Gualerzi C. O., Bläsi U. (2002). Leaderless mRNAs in bacteria: surprises in ribosomal recruitment and translational control. Mol. Microbiol. 43 239–246. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02739.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutalik V. K., Novichkov P. S., Price M. N., Owens T. K., Callaghan M., Carim S., et al. (2019). Dual-barcoded shotgun expression library sequencing for high-throughput characterization of functional traits in bacteria. Nat. Commun. 10:308. 10.1038/s41467-018-08177-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahigashi K., Takai Y., Kimura M., Abe N., Nakayashiki T., Shiwa Y., et al. (2016). Comprehensive identification of translation start sites by tetracycline-inhibited ribosome profiling. DNA Res. 23 193–201. 10.1093/dnares/dsw008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCBI (2018). NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Standards [Online]. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok/standards/ (accessed March 3, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus K., Landstorfer R., Fellner L., Simon S., Marx H., Ozoline O., et al. (2016). Translatomics combined with transcriptomics and proteomics reveals novel functional, recently evolved orphan genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7 (Ehec). BMC Genomics 17:133. 10.1186/s12864-016-2456-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus K., Landstorfer R., Simon S., Schober S., Wright P. R., Smith C., et al. (2017). Differentiation of ncRNAs from small mRNAs in Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933 (EHEC) by combined RNAseq and RIBOseq – ryhB encodes the regulatory RNA RyhB and a peptide, RyhP. BMC Genomics 18:216. 10.1186/s12864-017-3586-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Y., Sperandio V. (2012). Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:90. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]