Susan Weiss discusses the milestones of the coronavirus field and future perspectives on SARS-CoV-2 research.

Abstract

I have been researching coronaviruses for more than forty years. This viewpoint summarizes some of the major findings in coronavirus research made before the SARS epidemic and how they inform current research on the newly emerged SARS-CoV-2.

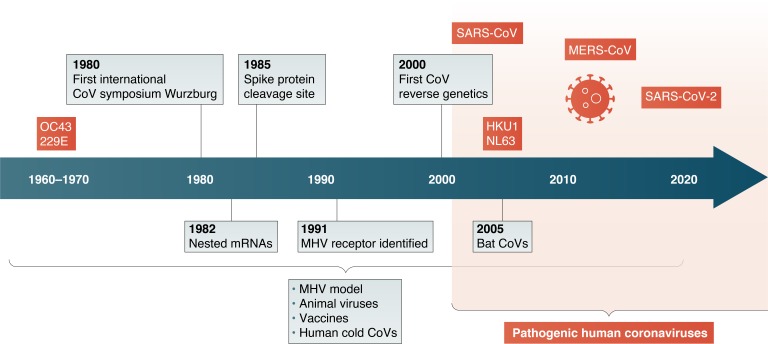

A virulent new coronavirus is currently holding hostage much of the human population worldwide. This virus, SARS-CoV-2, which causes the COVID-19 disease, emerged in China from bats into a presumed intermediate species and then into humans. It then spread around the globe with ongoing devastating effects. This round of human coronavirus disease follows the appearance of the related lethal coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, in 2002 and 2012 respectively. The emergence of SARS-CoV was the first time the general public, as well as many scientists, became aware of this group of viruses and its potential to cause lethal infections in humans. Indeed, each one of these events has instigated an influx of researchers into this field. However, there is a long history of coronavirus research, starting as early as the 1930s, that has built a large knowledge base as well as technical tools for investigating these human pathogens. As someone who has worked with this group of viruses since the end of my postdoctoral period in the late 1970s until the present, I want to review some of the major findings over the last 40 yr in the field, summarized in Fig. 1, and point out how they are relevant to the current coronavirus outbreak.

Figure 1.

Timeline for coronavirus research. Major findings in coronavirus research (gray boxes) as well as identification of human coronaviruses (red boxes) are indicated along the timeline.

Coronavirus researchers encompassed a small community in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As I was finishing my postdoctoral training with J. Michael Bishop and Harold Varmus at the University of California, San Francisco, working on the RNAs of avian sarcoma virus (Weiss et al., 1977), I realized I didn’t want to continue working in that field. In reading the literature, I came upon coronaviruses as an attractive topic, with so much possible. The model coronavirus, mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), was easy to grow in tissue culture in the laboratory and also provided compelling mouse models for human disease, especially those of the liver and the central nervous system. Julian Leibowitz, then at the University of California, San Diego, working on MHV, very generously shared his viruses and cells with me. Julian and I worked together at that time and have been friends and collaborators for the past 40 yr. It was not until much later that I appreciated the great gift of time Mike Bishop gave me to start my own future research while still in his laboratory.

Indeed, the first international coronavirus conference, organized by Volker ter Meulen, met in Wurzburg, Germany in the fall of 1980, the same year I started my laboratory as an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania, now the Perelman School of Medicine in September 1980. Dr. ter Meulen was passing through Philadelphia, and he invited me to this meeting. That meeting was attended by ∼60 people, which was virtually the entire coronavirus group at that time. This was the era during which the RNA genome and replication strategy used by this group of viruses was discovered. While many talks focused on the model coronavirus, MHV, others were presented on the replication of important coronaviruses of domesticated animals, including infectious bronchitis virus and bovine coronavirus. There were a handful of presentations on human coronavirus 229E, a poorly understood agent of the common cold.

Leaving that meeting, and with the encouragement and mentorship of Neal Nathanson, my chair, and Don Gilden, a professor in the neurology department, I was excited to expand my research to studies utilizing the MHV animal models of both encephalitis/chronic demyelinating disease and hepatitis. While far from my comfort zone of molecular biology, this was a new and exciting direction to explore. During the 1980s and 1990s, we made fundamental discoveries using the animal model, which was greatly enhanced in later years by the use of genetically modified viral strains by reverse genetics. Indeed, my career evolved in parallel to coronavirus research. It was also during this period that I was promoted to Associate Professor (1986) and Professor (1992).

During the 1980s, several important findings were reported. The coronavirus genomic RNA is transcribed into a set of subgenomic mRNAs that encode viral proteins. Using the model MHV, these subgenomic RNAs were shown to each contain a leader sequence derived from the 5′ end of the genome (Lai et al., 1982), initially by RNA fingerprinting methods. These nested subgenomic RNAs came to define a larger superfamily of Nidoviruses (“nidus” means nest) including several other virus families. Later it was found that subgenomic mRNAs are transcribed from negative strand RNAs that were synthesized from the full-length genomic RNA (Wu and Brian, 2010). This is a unique mechanism involving noncontiguous transcription of the genome, presumed to occur by a process involving viral polymerase jumping from one part of the genome template to another. This leads to a high rate of recombination for coronaviruses, which may play a role in viral evolution and interspecies infections. However, the ancestral bat virus of SARS-CoV-2, the species from which it was transferred to humans, and the sequence changes leading to the evolution of this highly pathogenic virus have yet to be identified.

Virions contain the genetic material and the structural proteins necessary for invasion. Early studies on the viral structural proteins by Kathryn Holmes and Larry Sturman (Frana et al., 1985) showed that the MHV spike protein (S, initially called E2) was synthesized as a precursor, and during intracellular processing, is proteolytically cleaved by the cellular enzyme furin into S1 and S2 subunits. Spike protein cleavage was required for cell-to-cell fusion during infection and was both cell type dependent and virus strain dependent. Much later, it was found that a second cleavage S2′ exposes the fusion peptide and is thus necessary for viral entry. These early findings informed many subsequent studies on SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, defining where cleavages occur and which proteases carry them out. These seemingly nuanced studies demonstrated that these details impact entry routes, cellular and organ tropism, and possibly antiviral targets (Millet and Whittaker, 2015). The sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was released within weeks of the outbreak, and it was clear that the SARS-COV-2 spike protein has a furin cleavage site in the S1/S2 junction, different from SARS-CoV and other closely related bat viruses (Coutard et al., 2020). This has implications for viral entry routes and possible protease inhibitors as antivirals, and has led to speculation about virulence and pathogenesis. Interestingly, this new furin site may serve as a marker to identify a possible precursor virus.

In addition to viral glycoprotein cleavages impacting tropism, defining the cellular receptor used by each coronavirus has also informed our understanding of infection. In 1991, Kathryn Holmes identified the MHV receptor as CEACAM1a (MHVR), a carcinoembryonic antigen family member (Williams et al., 1991), one of the earliest identified viral receptors. Subsequently, ACE2 for SARS-CoV and DPP4 for MERS were identified as receptors, and within only a short period of time, it was found that ACE2 is also used by SARS-CoV-2 (Zhou et al., 2020). However, while understanding the expression pattern of the receptor can define which cells can be infected, it does not mean all cells that express the receptor or even the cells with the highest expression are the major targets. This is exemplified by MHV studies in which the receptor, MHVR, is expressed highly in the liver but at barely detectable levels in neurons. In contrast, during infection, the MHV strain JHM.SD is highly neurovirulent and cannot replicate in the liver (Bender et al., 2010). We devoted considerable time and energy to mapping viral tropism in vivo and virulence factors that contributed to pathogenesis. Perhaps surprisingly, our studies showed it was not only the spike protein that impacted tissue tropism; other “background genes,” including nucleocapsid and replicase, as well as accessory genes, were also important determinants of tropism (reviewed in Weiss and Leibowitz, 2011). Therefore, one cannot infer pathogenesis from knowledge of the spike protein and receptor alone. Future studies on SARS-CoV-2 will define tissue tropism and whether it parallels SARS-CoV or not.

Sequencing RNA genomes was difficult in the 1980s, and cDNA cloning was just emerging. The first complete genome sequence of a coronavirus was for infectious bronchitis virus in 1987 (Boursnell et al., 1987) and a few years later it was completed for MHV (Lee et al., 1991). These genomes were assembled from many short cDNA clones and, when completed, indicated that the genome was ∼30 kb, significantly longer than had been estimated previously by sucrose gradient centrifugation, and that it was the longest of any known RNA virus. These sequences revealed two long open reading frames, ORF1a and 1b encoding 16 nonstructural proteins. It was also shown that both ORF1a and ORF1ab proteins were translated from genome RNA, and ORF1b via a translational frame shift at the end of ORF1a revealing new mechanisms of translational control (Bredenbeek et al., 1990). Alexander Gorbalenya’s insightful analyses of the proteins encoded in ORFs1a and 1b revealed several protease and other enzymatic domains (for example, ExoN, EndoU, and methylation enzymes) required for diverse aspects of replication and immune evasion. After the emergence of SARS-CoV, it became clear that there were some enzymes and proteins that were present in diverse coronaviruses and that there were other so-called accessory proteins that were species specific (Snijder et al., 2003). Understanding the roles of these virally encoded proteins will undoubtedly reveal how these viruses evade host-directed responses. Moreover, antivirals targeting one of the essential enzymes conserved across the coronavirus family may ultimately be developed as a pan anti-coronavirus therapy. Indeed, current trials with the antiviral remdesivir, which targets the conserved RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, may indeed be active against a large number of coronaviruses (Agostini et al., 2018).

Indeed, it became clear that these the coronavirus accessory genes played a fundamental role in innate immune evasion and pathogenesis. We found that a poorly understood MHV protein, NS2, was a liver-specific antagonist of host innate immunity, and with Robert Silverman, now a long-term collaborator and friend, we found that NS2 was a phosphodiesterase that cleaved 2-5A, the activator of the antiviral OAS-RNase L pathway (Zhao et al., 2012). This new research direction led to our two groups exploring several aspects of activation and antagonism of this pathway during infections with many viruses, as well as by endogenous double-stranded RNA that accumulates in certain autoimmune disease states. Importantly, we identified OAS-RNase L as a primary pathway that can be activated early in infection or during infections with viruses that shut down IFN production or signaling, and in bat cells as well as human cells (Li et al., 2019). During this period, we found that MERS NS4b was a structural homologue of NS2 but was different from other viral phosphodiesterases in its primarily nuclear localization, which is a current direction of our research. This new and still ongoing research direction led to our discovery of new aspects of innate immune regulation by MERS-CoV (Comar et al., 2019).

Another major obstacle for coronavirus research in the early days was the lack of a reverse genetics system, which in part was due to the difficulties of cloning a 30-kb RNA. A targeted recombination system was developed Paul Masters (Koetzner et al., 1992), which was followed by the construction of a full-length genome copy in a bacterial artificial chromosome by Luis Enjuanes (Almazán et al., 2000) and a full-length infectious cDNA clone by Ralph Baric (Yount et al., 2000). Genetic systems for multiple coronaviruses by these and other emerging methods quickly followed (Almazán et al., 2014). This allowed for genetic studies that revealed novel insights into both basic biology and viral pathogenesis and rapid construction of clones of the emerging coronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Almazán et al., 2014). Amazingly, a very recent manuscript by Volker Thiel and colleagues in 2020 describes the rapid cloning of the SARS-CoV-2 genome in a yeast-based system (Thao et al., 2020 Preprint). These genetic systems are essential to reveal mechanisms of pathogenesis and immune control.

The coronavirus outbreaks had significant impacts on the previously small and cohesive coronavirus field. The discovery that a coronavirus is the etiologic agent of the SARS epidemic shocked coronavirologists, and we all began to work on the new SARS-CoV using all we had learned previously. As is now well known, but was not clear at the time, SARS disappeared after ∼6 or 7 mo with 8,069 infections and 774 deaths. As the virus disappeared, the number of people working on coronaviruses diminished. Following the SARS epidemic, two other human coronaviruses were identified, NL63 (croup, bronchiolitis; Pyrc et al., 2004) and HKU1 (pneumonia; Lau et al., 2006). Another notable finding was the discovery that bats were the hosts for many SARS-like coronaviruses (Li et al., 2005; Lau et al., 2005). When the more deadly MERS-CoV emerged in 2012, this rekindled the widespread interest in coronaviruses. However, there were important differences in the emergence of MERS-CoV, as it was found to have a reservoir in the intermediate animal, the camel, and continues to this day to spread from camel to human. Maybe this should have warned us that coronaviruses may emerge in different ways and spread with different patterns, as we have observed from SARS-CoV-2.

The latest outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 has paralyzed the world, and the scientific community is mobilized. My laboratory has recently begun to lend our expertise to investigations of SARS-CoV-2, both in our own work on virus–host interactions and in collaboration with others on diverse topics from diagnostics to antivirals. Moreover, it is gratifying that a number of people who trained with me are contributing to the effort to fight this virus, including Scott Hughes (New York City Office of Safety and Emergency Preparedness & Response) and Kristine Rose (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) as well as several others carrying out bench research on SARS-CoV-2. Hopefully all the knowledge we have from the previous coronaviruses will accelerate the discovery of antivirals and vaccine development, as well as the source of the virus and its ancestral parent. Hopefully this time we can learn enough to prevent or quickly combat any future outbreaks. Perhaps ironically, the XV International Nidovirus Symposium (formerly Coronavirus) scheduled for May 2020 has been postponed for a year due to SARS-CoV-2. We eagerly await the next face-to-face gathering of the ever-growing coronavirus research family.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Sara Cherry and Beth Schachter for significant contributions to writing this Viewpoint.

References

- Agostini M.L., et al. MBio. 2018 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almazán F., et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000 doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almazán F., et al. Virus Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.05.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bender S.J., et al. J. Virol. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02688-09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boursnell M.E., et al. J. Gen. Virol. 1987 doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bredenbeek P.J., et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990 doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comar C.E., et al. MBio. 2019 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00319-19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coutard B., et al. Antiviral Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frana M.F., et al. J. Virol. 1985 doi: 10.1128/JVI.56.3.912-920.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koetzner C.A., et al. J. Virol. 1992 doi: 10.1128/JVI.66.4.1841-1848.1992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M.M., et al. J. Virol. 1982 doi: 10.1128/JVI.41.2.557-565.1982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K., et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S.K., et al. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02614-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.J., et al. Virology. 1991 doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90071-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., et al. Science. 2005 doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., et al. MBio. 2019 doi: 10.1128/mBio.02414-19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millet J.K., and Whittaker G.R. Virus Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrc K., et al. Virol. J. 2004 doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-1-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder E.J., et al. J. Mol. Biol. 2003 doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thao T.T.N., et al. 2020. bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.21.959817v1 (Preprint posted February 21, 2020).

- Weiss S.R., et al. 1977. Cell. 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90163-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S.R., and Leibowitz J.L. Adv. Virus Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385885-6.00009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R.K., et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991 doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.Y., and Brian D.A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000378107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yount B., et al. J. Virol. 2000 doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.22.10600-10611.2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., et al. Cell Host Microbe. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., et al. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]