Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between ambient air pollution and stroke morbidity in different subgroups and seasons.

Methods

We performed a time-series analysis based on generalised linear models to study the short-term exposure–response relationships between air pollution and stroke hospitalisations, and conducted subgroup analyses to identify possible sensitive populations.

Results

For every 10 µg/m3 increase in the concentration of air pollutants, across lag 0–3 days, the relative risk of stroke hospitalisation was 1.029 (95% CI 1.013 to 1.045) for PM2.5, 1.054 (95% CI 1.031 to 1.077) for NO2 and 1.012 (95% CI 1.002 to 1.022) for O3. Subgroup analyses showed that statistically significant associations were found in both men and women, middle-aged and older populations, and both cerebral infarction and intracerebral haemorrhage. The seasonal analyses showed that statistically significant associations were found only in the winter.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that short-term exposure to PM2.5, NO2 and O3 may induce stroke morbidity, and the government should take actions to mitigate air pollution and protect sensitive populations.

Keywords: epidemiology, public health, stroke medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study investigated the association between air pollution and subtypes of stroke morbidity.

This study included more than 67 000 cases, ensuring high statistical power.

The modification effects of different demographic characteristics and seasons were explored.

Being a single-city study limited the generalisation of the findings.

Associations between air pollution and stroke hospitalisations did not prove causality.

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and mortality, accounting for approximately 132 million DALYs and 6.2 million deaths globally in 2017.1 2 It is also the leading cause of long-term adult disability and the leading cause of death in China; 20.19% of total deaths were caused by stroke in 2017,3 4 and the age-standardised incidence and mortality rates were 246.8 and 114.8 per 100 000 person-years, respectively.5 Well-known risk factors of stroke include history of hypertension, current smoking status and alcohol intake.6

With the deterioration of global air quality, concerns have been raised about the relationship between ambient air pollution and stroke. According to the Global Burden of Disease, approximately 12.75% of stroke cases in China in 2017 were linked to air pollution.3 Possible mechanisms linking ambient air pollution to stroke include inflammation, oxidative stress, atherosclerosis and autonomic dysregulation.7 To date, most of the relevant epidemiological studies have focused on stroke mortality instead of morbidity,8 9 but it should be noted that morbidity is more indicative of the early stages of stroke; early prevention of stroke has an important public health significance. Studies that examined the relationship between ambient air pollution and stroke morbidity obtained inconsistent results, and most of them studied the association over a full year but failed to consider the seasonal differences in pollutant concentration and their health effects.10–12

In this study, a time-series analysis was conducted to investigate the association between ambient air pollution and stroke morbidity in different seasons; we also researched possible sensitive populations by conducting subgroup analyses by sex, age group, education level and stroke subtypes.

Materials and methods

Study area

Shenzhen is located within the Pearl River Delta, China, is 1 degree south of the Tropic of Cancer and has a permanent population of approximately 12.5 million people.13 Because of the Siberian anticyclone, it has a warm and humid subtropical climate. Six kinds of air pollutants, including ozone (O3), fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), inhalable particulate matter (PM10), sulfur dioxide (SO2) and carbon monoxide, are monitored in Shenzhen, and the main ambient air pollutants are O3, PM2.5 and NO2.

Data collection

Stroke data containing 67 078 cases from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2016 were collected from the Shenzhen Centre for Chronic Disease Control. Sixty-nine hospitals from 10 administrative districts reported their stroke case information (including patient age and sex, clinical diagnosis and classification, onset date, diagnosis date and major risk factors) to the Shenzhen Centre for Chronic Disease Control. All the cases were coded according to the WHO's International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, ranging from I60 to I64: (1) subarachnoid haemorrhage, which was coded as I60; (2) intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), which was coded as I61; (3) other non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhage, which was coded as I62; (4) cerebral infarction (CBI), which was coded as I63; and (5) stroke not specified as haemorrhage or infarction, which was coded as I64. All cases were diagnosed in the hospital with CT, MRI or neurological examination. In the subgroup analysis for stroke subtypes, we focused on ICH and CBI, which accounted for 94.8% of all stroke cases.

Hourly concentrations of O3, PM2.5 and NO2 were obtained from the National Urban Air Quality Real-time Publishing Platform (http://106.37.208.233:20035/). The daily mean concentrations for each air pollutant were averaged from all the 11 fixed-site air pollution monitoring stations in Shenzhen.14 Daily meteorological data were obtained from the National Meteorological Data Sharing Platform (http://data.cma.cn/), including the daily mean, maximum and minimum temperatures, the mean relative humidity, the mean wind speed and the mean atmospheric pressure.

Statistical modelling

This time-series analysis adopted generalised linear Poisson models to estimate the association between air pollutants and stroke hospitalisations.15 The daily mean concentrations of air pollutant (PM2.5, NO2 or O3) were the independent variables, and the number of daily hospital admissions for stroke was the dependent variable. Meteorological variables (ie, temperature, relative humidity and air pressure), long-term trends and seasonal patterns, as well as day of the week, were used as adjustment variables. The influence of other pollutants was examined in two-pollutant models.

Considering the possible delayed and/or cumulative effects of air pollution on stroke morbidity, we created cross-basis matrix for air pollutants, within the framework of distributed lag linear model.16 The selection of lag days was justified by the polynomial lag models.

The model to represent the relationship between the daily mean concentration of air pollutants and hospital admissions for stroke is as follows:

Here, indicates the expected number of hospital admissions for stroke on day t; is the cross-basis matrix of the air pollutants (PM2.5, NO2 or O3), with as the corresponding vector of coefficients; and is the natural cubic spline function. is a dummy variable for the day of week. We used 7 df per year for the time trend (), 3 df for the previous 14 days' moving average temperature ()17 18 and 3 df for both the relative humidity () and the air pressure () on day t; the choice of df for each variable was based on the Akaike Information Criterion for quasi-Poisson models.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for different sexes, age groups (<40, 40–64 and ≥65 years), education levels (primary school or below, junior high school, high school or above) and stroke subtypes (CBI and ICH). When comparing seasonal differences, we defined spring as the period from 1 March to 31 May, summer as the period from 1 June to 31 August, autumn as the period from 1 September to 30 November and winter as the period from 1 December to 28 February of the next year. The differences among the effect estimates between different subgroups were tested via the Z-test.19 Sensitivity analyses were performed by adjusting the df values of and , as well as the number of lags considered for the air pollutant. All results were reported as relative risks (RRs) and 95% CIs of hospital admissions for stroke for every 10 µg/m3 increase in air pollutant exposure, and two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Main analyses were performed using the ‘dlnm’ and ‘splines’ packages in R V.3.5.1.

Patient and public involvement

This study belongs to ecological research and does not reveal any personal information; patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination of our research. Therefore, patients did not have to be asked for informed consent.

Results

Data description

In total, during 2014–2016, 67 078 hospital admissions for stroke were recorded, of which 77.8% were first-time cases, and 61.9% were men. Patients aged 40–64 years accounted for 49.3% of the total, and 44.7% were older (age ≥65 years old). In total, 27.7% of the cases had an education level of primary school or below; 39.8% completed junior high school; and 32.5% had a high school education or higher. Among the subtypes of stroke, CBI and ICH accounted for 52 168 (77.8%) and 11 415 (17.0%), respectively. The other three subtypes accounted for approximately 5% of the total (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of stroke hospitalisations in Shenzhen

| Variables | Number | Percentage (%) |

| Stroke cases | 67 078 | 100.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 41 546 | 61.9 |

| Female | 25 526 | 38.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <40 | 4051 | 6.0 |

| 40–64 | 33 053 | 49.3 |

| ≥65 | 29 968 | 44.7 |

| Education | ||

| Primary school or below | 18 558 | 27.7 |

| Junior high school | 26 686 | 39.8 |

| High school or above | 21 792 | 32.5 |

| Stroke subtypes | ||

| Cerebral infarction | 52 168 | 77.8 |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 11 415 | 17.0 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 2369 | 3.5 |

| Stroke not specified as haemorrhage or infarction | 219 | 0.3 |

| Other non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhage | 783 | 1.2 |

On average, there were approximately 61 hospital admissions for stroke per day during our study period, and the 24 hours mean concentrations of PM2.5, NO2 and O3 were 30.1, 33.2 and 56.9 µg/m3, respectively. The daily mean temperature was 23.5°C; the mean relative humidity was 74.7%; and the daily mean air pressure was 1005.7 hPa (table 2). In general, the pollutant concentrations of PM2.5 and NO2 were higher in winter than in other seasons (online supplementary table S1). Correlations between air pollutants and meteorological factors are in table 3.

Table 2.

Distribution of daily air pollution concentrations, meteorological factors and stroke hospitalisations in Shenzhen

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | P25 | P50 | P75 | Max |

| Air pollutants | |||||||

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 30.1 | 16 | 6.3 | 16.8 | 27 | 39.9 | 96.1 |

| NO2 (μg/m3) | 33.2 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 25 | 31 | 39.5 | 84.8 |

| O3 (μg/m3) | 56.9 | 22.1 | 16.9 | 38.8 | 52.9 | 71.9 | 147.8 |

| Meteorological factors | |||||||

| Temperature (℃) | 23.5 | 5.7 | 3.5 | 19.0 | 25.1 | 28.2 | 33.0 |

| Relative humidity (%) | 74.7 | 12.2 | 19.0 | 69.0 | 76.0 | 83.0 | 99.0 |

| Air pressure (hPa) | 1005.6 | 6.6 | 986.8 | 1000.7 | 1005.3 | 1010.6 | 1027.3 |

| Stroke cases | |||||||

| All strokes | 61.2 | 15.7 | 23.0 | 51.0 | 59.0 | 70.0 | 182.0 |

| Type | |||||||

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 10.4 | 4.2 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 13.0 | 40.0 |

| Cerebral infarction | 47.6 | 13.1 | 17.0 | 39.0 | 46.0 | 54.0 | 143.0 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 37.9 | 10.2 | 15.0 | 31.0 | 37.0 | 43.0 | 113.0 |

| Female | 23.3 | 7.4 | 7.0 | 18.0 | 22.0 | 27.0 | 77.0 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <40 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 |

| 40–64 | 30.2 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 24.0 | 30.0 | 35.0 | 90.0 |

| ≥65 | 27.3 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 21.0 | 26.0 | 32.0 | 101.0 |

| Education | |||||||

| Primary school or below | 16.9 | 5.4 | 3.0 | 13.0 | 16.0 | 20.0 | 51.0 |

| Junior high school | 24.4 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 19.0 | 23.0 | 29.0 | 85.0 |

| High school or above | 19.9 | 7.6 | 5.0 | 14.0 | 19.0 | 24.0 | 67.0 |

NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM2.5, fine particulate matter.

Table 3.

Spearman’s rank coefficients between daily mean air pollutants and meteorological variables

| Variables | PM2.5 | NO2 | O3 | Temperature | Relative humidity | Air pressure |

| PM2.5 | 1.00 | |||||

| NO2 | 0.55* | 1.00 | ||||

| O3 | 0.56* | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||

| Temperature | −0.43* | −0.27* | −0.09* | 1.00 | ||

| Relative humidity | −0.53* | −0.1* | −0.51* | 0.27* | 1.00 | |

| Air pressure | 0.50* | 0.26* | 0.21* | −0.85* | −0.45* | 1.00 |

*P<0.05.

NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM2.5, fine particulate matter.

bmjopen-2019-032974supp001.pdf (139.7KB, pdf)

Regression analysis

When the lag length was set as 7 days, the results showed that the lag effect mainly lasted for 3 days (online supplementary figure S1). Therefore, we used 3 days as the lag length in later analyses. Positive associations and lag effects were observed between stroke morbidity and air pollution. The cumulative effect of a 10 µg/m3 increase in PM2.5 concentrations across lag 0–3 days corresponded to a 2.9% (95% CI 1.3% to 4.5%) increase in daily stroke hospitalisations; it was a 5.4% (95% CI 3.1% to 7.7%) increase in the case of NO2, and a 1.2% (95% CI 0.2% to 2.2%) increase for O3.

Table 4 showed that, for PM2.5, an association was found in both men and women, populations older than 40 years old and people with education levels of junior high school and above, and the CBI stroke subtype. For NO2, the association was consistently significant in both men and women, populations in all age groups and all education levels, and subtypes CBI and ICH. For O3, the association was significant in women, the middle-aged population, populations with an education level of junior high school and the CBI stroke subtype. The associations occurred mainly in the winter. Comparing the effect estimates between different subgroups, we found none of the differences to be statistically significant.

Table 4.

RRs (95% CI) of stroke hospitalisations for every 10 µg/m3 increase in ambient PM2.5, NO2 and O3 in the single-pollutant model, across lag 0–3 days

| Subgroups | RR (95% CI) | ||

| PM2.5 | NO2 | O3 | |

| All strokes | 1.029 (1.013 to 1.045) |

1.054 (1.031 to 1.077) |

1.012 (1.002 to 1.022) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.029 (1.011 to 1.046) |

1.056 (1.032 to 1.080) |

1.011 (0.999 to 1.022) |

| Female | 1.030 (1.009 to 1.052) |

1.050 (1.020 to 1.080) |

1.013 (1.000 to 1.027) |

| Age | |||

| <40 | 1.030 (0.990 to 1.070) |

1.084 (1.027 to 1.145) |

0.998 (0.974 to 1.023) |

| 40–64 | 1.025 (1.008 to 1.044) |

1.058 (1.033 to 1.084) |

1.013 (1.002 to 1.024) |

| >65 | 1.033 (1.012 to 1.055) |

1.046 (1.017 to 1.076) |

1.012 (0.999 to 1.025) |

| Education | |||

| Primary and below | 1.013 (0.991 to 1.036) |

1.050 (1.019 to 1.081) |

1.007 (0.993 to 1.021) |

| Junior high school | 1.043 (1.021 to 1.065) |

1.072 (1.041 to 1.104) |

1.023 (1.009 to 1.037) |

| Senior high school and above | 1.028 (1.006 to 1.049) |

1.036 (1.007 to 1.066) |

1.003 (0.990 to 1.016) |

| Stroke subtype | |||

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 1.021 (0.995 to 1.048) |

1.058 (1.021 to 1.096) |

1.008 (0.991 to 1.025) |

| Cerebral infarction | 1.029 (1.011 to 1.047) |

1.050 (1.026 to 1.075) |

1.012 (1.001 to 1.023) |

| Season | |||

| Spring | 1.031 (0.989 to 1.076) |

1.034 (0.989 to 1.081) |

1.012 (0.989 to 1.035) |

| Summer | 1.031 (0.989 to 1.075) |

0.992 (0.944 to 1.044) |

1.015 (0.990 to 1.041) |

| Autumn | 1.021 (0.993 to 1.050) |

1.040 (0.994 to 1.089) |

1.009 (0.992 to 1.025) |

| Winter | 1.073 (1.022 to 1.126) |

1.095 (1.024 to 1.170) |

1.033 (0.983 to 1.086) |

NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM2.5, fine particulate matter; RR, relative risk.

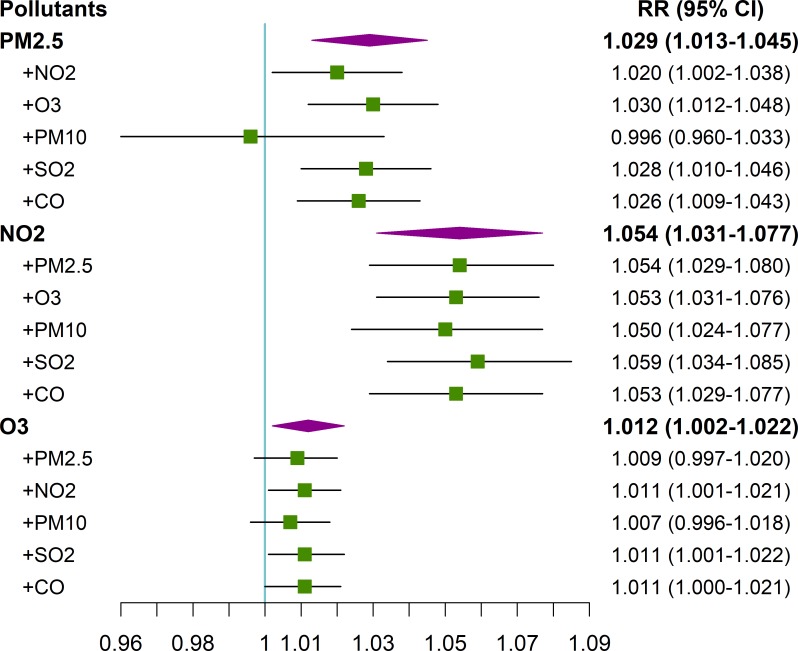

For the two-pollutant model (figure 1), the results did not vary substantially compared with those in the single-pollutant models, especially for NO2. The results were stable after adjusting the df values of and , as well as the number of lags considered for the air pollutant in the model, indicating the stability of the estimated effects (online supplementary tables S2 and S3).

Figure 1.

RRs (95% CI) of stroke hospitalisations for every 10 µg/m3 increase in ambient PM2.5, NO2 and O3 in the two-pollutant model, across lag 0–3 days. CO, carbon monoxide; NO2, nitrogen dioxide; O3, ozone; PM10, inhalable particulate matter; PM2.5, fine particulate matter; RR, relative risk; SO2, sulfur dioxide.

Discussion

In this study, a positive association was found between the daily stroke hospitalisations and the concentration of ambient PM2.5. Previous studies showed inconsistent results when exploring the short-term associations between PM2.5 and stroke morbidity. Some studies observed a non-significant association, while other studies found a significant positive association.10 20 For example, a 2014 meta-analysis of nonfatal strokes found an RR of 0.7%–0.8% for short-term effects per 10 µg/m3 PM2.5.21 Exposure to particulate matter increases inflammation, antioxidant activity and circulating blood platelet activation, and decreases vascular endothelial functions and enzyme activity, the latter of which may increase peripheral thrombosis and blood clotting.22–24 Furthermore, compared with PM10, PM2.5 has a smaller size and larger surface area and can carry more harmful substances and penetrate deep into the human body,25 finally inducing a stroke.

We found that daily stroke hospitalisations increased by 5.4% for every 10 µg/m3 increase of NO2. These results are similar to those of previous studies, but some of the previous studies obtained different effect estimates.26–28 For example, a study in Wuhan, China, showed a 2.9% increase in stroke hospitalisations per 10 µg/m3 increase in NO2 in the cold season, which was smaller than the result (9.5%) from our study.29 Evidence has shown that NO2 is related to plasma fibrinogen30 and is also correlated with PM2.5, which leads to increased coagulability through the release of cytokines.28 Gaseous NO2 can also be mixed with water to form acid aerosols after inhalation, which damages health through a series of oxidation mechanisms.31

The study found that the RR of stroke associated with an increase in the level of air pollution from the first to the third quartile was slightly higher for NO2 than for PM2.5. Previous studies showed similar results14 32; gaseous pollutants appeared to have a stronger effect on stroke mortality,33 34 and some studies indicated that, after adjusting for other pollutants, only NO2 showed consistent results with a single-pollutant model.35 36 Concern has been raised that the observed health effects associated with NO2 might be a result of exposure to traffic-related emissions or fine particles.37

A weak positive association between O3 and hospital admissions for stroke was found in our study. Previous studies exploring this relationship showed different results. For example, a 10-year study conducted in France showed a significant positive relationship between O3 exposure and ischaemic stroke in men over 40 years of age, and the result was observed for a 1‐day lag (OR 1.133, 95% CI 1.052 to 1.220).38 In the USA, where air pollution levels are low, the incidence of CBI/transient ischaemic attack was also associated with O3 exposure.39 However, there was no statistically significant association found between O3 pollution and the incidence of stroke in South Carolina and Nueces County, Texas.40 41 Some studies even showed a significant or non-significant negative association between O3 and CBI.42 43 The mechanisms linking O3 and stroke need to be further studied.

The associations were found in both men and women; no clear trends were found across age groups and education levels. We found that the associations between air pollution and stroke morbidity had no statistically significant differences between different age groups. Similar results have been found in some previous studies.14 44 Elderly people may spend more time indoors, and they are likely to wear masks when air pollution is severe; thus, their individual exposure may be less.45 On the other hand, Tian et al found that the associations between air pollution and stroke morbidity were stronger in the elderly.32 Therefore, the modification effect of age on the associations between air pollution and stroke morbidity needs further study. In addition, vascular risk factors, such as hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, may also modify these associations, which needs to be addressed in future research.

The seasonal analyses showed that statistically significant associations between ambient air pollutant concentrations and hospital admissions for stroke were only found in the winter; Dong et al also found that the harmful effects of NO2 and SO2 were more robust in the cold season.14 One possible reason for this result is that the air pollution concentrations in Shenzhen are higher in winter than in summer (online supplementary table S1). The substances carried by particles may vary between seasons, which would influence the effect.

Our study found that PM2.5, NO2 and O3 were related to hospitalisations for CBI but found different results for ICH. Similarly, previous studies showed consistent associations between CBI and air pollution, while the association between ICH was more variable and had a higher imprecision.46 One reason is that the prevalence of ICH was much lower than CBI. In our study, 77.8% of stroke hospitalisations were for CBI, and ICH only accounted for 17.0% of stroke hospitalisations. Therefore, the risk estimates for ICH were more imprecise, and the CI of the RR for ICH was wider. Another reason may be the differential mechanisms linking air pollution exposure to CBI and ICH. PM2.5 exposure is conducive to atherosclerosis and the oxidative stress of the heart. These conditions may upregulate visfatin, reduce heart rate variability and induce CD36-dependent 7-ketocholesterol, which accumulate in macrophages.47–50 All of these factors are more likely to induce CBI than ICH.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the air pollution data from fixed-site monitoring stations may not be representative of average population exposure. For example, the air pollution concentrations near the main roads with heavy traffic were often higher than those near the parks with few vehicles, and the air pollution monitoring stations were usually located far away from the main roads with heavy traffic. Second, it is difficult to completely eliminate the possibility of ecological fallacy in time-series studies, and we cannot provide absolute risks in this study. Moreover, the associations observed in the present study cannot prove causality.

Conclusions

PM2.5, NO2 and O3 may induce stroke morbidity, especially in the winter. All three air pollutants were associated with higher risks of hospital admission due to CBI, the most prevalent stroke subtype in the study location. The government should take actions to address air pollution issues and develop warning systems for sensitive populations during high-risk periods.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

YG and XX contributed equally.

Contributors: The study was conceived and designed by JB, JP and YG; XX and YG conducted statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; LL, HZ, and SD contributed to data collection and processing; YX and ZL helped in study management and the interpretation of the results; JB, JP and CH reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0606200), Shenzhen Science and Technology Project (grant number JCYJ20170303104937484), Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (grant number SZSM201911015) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2017M612827).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The institutional review board at the School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, approved the study protocol (number 2019-029) with a waiver of informed consent. Data were analysed at the aggregate level. All patients were anonymous, and no patient privacy were revealed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Stanaway JD, Afshin A, Gakidou E, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet 2018;392:1859–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1736–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) GBD compare data visualization Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington, 2018. Available: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare [Accessed 24 Feb 2018].

- 4.Jia Q, Liu L-P, Wang Y-J. Stroke in China. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2010;37:259–64. 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Jiang B, Sun H, et al. Prevalence, Incidence, and Mortality of Stroke in China: Results from a Nationwide Population-Based Survey of 480 687 Adults. Circulation 2017;135:759–71. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet 2010;376:112–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ljungman PL, Mittleman MA. Ambient air pollution and stroke. Stroke 2014;45:3734–41. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.003130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang R, Liu G, Jiang Y, et al. Acute effects of particulate air pollution on ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke mortality. Front Neurol 2018;9:827 10.3389/fneur.2018.00827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C, Yin P, Chen R, et al. Ambient carbon monoxide and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide time-series analysis in 272 cities in China. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2:e12–18. 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30181-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher JA, Puett RC, Laden F, et al. Case-Crossover analysis of short-term particulate matter exposures and stroke in the health professionals follow-up study. Environ Int 2019;124:153–60. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng W, Zhang Y, Wang L, et al. Ambient fine particulate pollution and daily morbidity of stroke in Chengdu, China. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206836 10.1371/journal.pone.0206836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo P, Wang Y, Feng W, et al. Ambient air pollution and risk for ischemic stroke: a short-term exposure assessment in South China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091091. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Sep 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shenzhen statistics bureau, Nbs survey office in Shenzhen. Shenzhen statistical YEARBOOK 2018.

- 14.Dong H, Yu Y, Yao S, et al. Acute effects of air pollution on ischaemic stroke onset and deaths: a time-series study in Changzhou, China. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020425 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng RD, Dominici F, Louis TA. Model choice in time series studies of air pollution and mortality. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2006;169:179–203. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00410.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasparrini A, Linear DL. And non-linear models in R: the package dlnm. J Stat Softw 2011;43:1–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng W, Li H, Wang S, et al. Short-term PM10 and emergency department admissions for selective cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in Beijing, China. Sci Total Environ 2019;657:213–21. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet 2015;386:369–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ 2003;326:219–19. 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talbott EO, Rager JR, Benson S, et al. A case-crossover analysis of the impact of PM(2.5) on cardiovascular disease hospitalizations for selected CDC tracking states. Environ Res 2014;134:455–65. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin HH, Fann N, Burnett RT, et al. Outdoor fine particles and nonfatal strokes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology 2014;25:835–42. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemmar A, Hoet PHM, Dinsdale D, et al. Diesel exhaust particles in lung acutely enhance experimental peripheral thrombosis. Circulation 2003;107:1202–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000053568.13058.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delfino RJ, Staimer N, Tjoa T, et al. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation, antioxidant activity, and platelet activation are associated with primary combustion aerosols in subjects with coronary artery disease. Environ Health Perspect 2008;116:898–906. 10.1289/ehp.11189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills NL, Törnqvist H, Gonzalez MC, et al. Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1075–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa066314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Y, Zou J, Yang W, et al. A review of recent advances in research on PM2.5 in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:438 10.3390/ijerph15030438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heli- yun GUX-hXUR-fYUX Effects of major ambient air pollutants on Cardio-cerebrovascular diseases in Qingpu district. Journal of Labour Medicine 2014;31:921–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu-qing Z. Relationship between air pollution and emergency Hospital visits for stroke in Changsha: a case-crossover study. Journal of Environment and Health 2014;31:764–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villeneuve PJ, Chen L, Stieb D, et al. Associations between outdoor air pollution and emergency department visits for stroke in Edmonton, Canada. Eur J Epidemiol 2006;21:689–700. 10.1007/s10654-006-9050-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang H, Mertz KJ, Arena VC, et al. Estimation of short-term effects of air pollution on stroke hospital admissions in Wuhan, China. PLoS One 2013;8:e61168 10.1371/journal.pone.0061168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pekkanen J, Brunner EJ, Anderson HR, et al. Daily concentrations of air pollution and plasma fibrinogen in London. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:818–22. 10.1136/oem.57.12.818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mustafa MG, Tierney DF. Biochemical and metabolic changes in the lung with oxygen, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide toxicity. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978;118:1061–90. 10.1164/arrd.1978.118.6.1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian Y, Liu H, Zhao Z, et al. Association between ambient air pollution and daily hospital admissions for ischemic stroke: a nationwide time-series analysis. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002668 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong Y-C, Lee J-T, Kim H, et al. Effects of air pollutants on acute stroke mortality. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:187–91. 10.1289/ehp.02110187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moolgavkar SH. Air pollution and daily mortality in three U.S. counties. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:777–84. 10.1289/ehp.00108777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen R, Zhang Y, Yang C, et al. Acute effect of ambient air pollution on stroke mortality in the China air pollution and health effects study. Stroke 2013;44:954–60. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.673442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samoli E, Aga E, Touloumi G, et al. Short-Term effects of nitrogen dioxide on mortality: an analysis within the APHEA project. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1129–38. 10.1183/09031936.06.00143905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarnat JA, Brown KW, Schwartz J, et al. Ambient gas concentrations and personal particulate matter exposures: implications for studying the health effects of particles. Epidemiology 2005;16:385–95. 10.1097/01.ede.0000155505.04775.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henrotin JB, Besancenot JP, Bejot Y, et al. Short-Term effects of ozone air pollution on ischaemic stroke occurrence: a case-crossover analysis from a 10-year population-based study in Dijon, France. Occup Environ Med 2007;64:439–45. 10.1136/oem.2006.029306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lisabeth LD, Escobar JD, Dvonch JT, et al. Ambient air pollution and risk for ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Ann Neurol 2008;64:53–9. 10.1002/ana.21403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montresor-López JA, Yanosky JD, Mittleman MA, et al. Short-Term exposure to ambient ozone and stroke hospital admission: a case-crossover analysis. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2016;26:162–6. 10.1038/jes.2015.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wing JJ, Adar SD, Sánchez BN, et al. Short-Term exposures to ambient air pollution and risk of recurrent ischemic stroke. Environ Res 2017;152:304–7. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Y, Dong H, Yao S, et al. Protective effects of ambient ozone on incidence and outcomes of ischemic stroke in Changzhou, China: a time-series study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1610 10.3390/ijerph14121610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mechtouff L, Canoui-Poitrine F, Schott A-M, et al. Lack of association between air pollutant exposure and short-term risk of ischaemic stroke in Lyon, France. Int J Stroke 2012;7:669–74. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian Y, Xiang X, Wu Y, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and first hospital admissions for ischemic stroke in Beijing, China. Sci Rep 2017;7:3897 10.1038/s41598-017-04312-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.China: the air pollution capital of the world. Lancet 2005;366:1761–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67711-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wellenius GA, Schwartz J, Mittleman MA. Air pollution and hospital admissions for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke among Medicare beneficiaries. Stroke 2005;36:2549–53. 10.1161/01.STR.0000189687.78760.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pei Y, Jiang R, Zou Y, et al. Effects of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) on systemic oxidative stress and cardiac function in ApoE−/− mice. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:484 10.3390/ijerph13050484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wan Q, Cui X, Shao J, et al. Beijing ambient particle exposure accelerates atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout mice by upregulating visfatin expression. Cell Stress Chaperones 2014;19:715–24. 10.1007/s12192-014-0499-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rao X, Zhong J, Maiseyeu A, et al. Cd36-Dependent 7-ketocholesterol accumulation in macrophages mediates progression of atherosclerosis in response to chronic air pollution exposure. Circ Res 2014;115:770–80. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cho C-C, Hsieh W-Y, Tsai C-H, et al. In vitro and in vivo experimental studies of PM2.5 on disease progression. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1380 10.3390/ijerph15071380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-032974supp001.pdf (139.7KB, pdf)