Abstract

Universal health coverage (UHC) is driving the global health agenda. Many countries have embarked on national policy reforms towards this goal, including China. In 2009, the Chinese government launched a new round of healthcare reform towards UHC, aiming to provide universal coverage of basic healthcare by the end of 2020. The year of 2019 marks the 10th anniversary of China’s most recent healthcare reform. Sharing China’s experience is especially timely for other countries pursuing reforms to achieve UHC. This study describes the social, economic and health context in China, and then reviews the overall progress of healthcare reform (1949 to present), with a focus on the most recent (2009) round of healthcare reform. The study comprehensively analyses key reform initiatives and major achievements according to four aspects: health insurance system, drug supply and security system, medical service system and public health service system. Lessons learnt from China may have important implications for other nations, including continued political support, increased health financing and a strong primary healthcare system as basis.

Keywords: health policy, health systems, public health

Summary box.

Continued political support is the most important enabling condition for achieving universal health coverage (UHC). China has shown clear political willingness to make UHC achievement a more country-led process.

Increasing health financing is necessary, and the investment from both government and private sector is considered.

A strong primary healthcare system should be regarded as a core component in realising UHC. The Chinese government has made primary healthcare a priority in its ‘Healthy China 2030’ strategy.

Some lessons providing reform experiences for other countries include the pilot reform and systematic reform strategy.

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) is driving the global health agenda and is now an ambition for many nations at all stages of development.1 2 UHC is a means for achieving improved equity, health, financial well-being and economic development, ensuring that everyone has access to quality, affordable health services when needed.3 Most countries have made UHC a key global health objective through the United Nations’ resolution, and move towards UHC following the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set in 2015. At the beginning of the 21st century, the push for UHC seems stronger than ever.4 The new WHO director general, Dr Tedros, emphasised that UHC is the ‘top strategic priority’ in the road map for WHO’s renewal.5 Accordingly, WHO’s General Program of Work for 2019–2023 has set an ambitious goal of benefiting more than 1 billion people from UHC by 2023.6

WHO states that there is ‘no one size to fit all’—there are different ways to attain UHC. An increasing number of low and middle-income countries (LMIC) are actively pursuing policies to achieve UHC and share their implementation experience from different political settings, such as Turkey,7 Indonesia,8 Thailand9 and Bangladesh.10 According to The World Bank report, the march to UHC in China is unparalleled.11 Also, Yip et al commented that ‘China’s reform goals and systemic strategies are exemplary for other nations that pursue UHC.’12 In early 2009, the Chinese government launched a new round of health system reform with the goal of providing affordable and equitable basic healthcare for all by 2020, which is in line with the basic concept of UHC defined by WHO.13 This year marks the 10th anniversary of China’s most recent healthcare reform. Evidence from China is especially timely for countries pursuing UHC. However, much of the early research focused solely on the first 3-year reform after 2009 in China, without addressing the issue of the reform evolution and progress during the past decade. There is inadequate understanding of how China moves towards UHC step by step. We undertook a literature review, and analysed policies and secondary data from governmental sources. We aim to share the complete experience and strategy about China’s healthcare reform, and provide the critical lessons for other nations, especially for LMICs.

Analysis of the context

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) covers approximately 9.6 million km2, and is now the most populous country in the world with 1.42 billion people.14 The urban population accounts for 58.0% of the total population.15 PRC was founded on 1 October 1949. At the time, China had one of the world’s poorest healthcare delivery systems due to an economy weakened by war.16 Today, China is an upper middle-income country whose gross domestic product has grown substantially at an average annual rate of 9.5% over the past 40 years, and has lifted more than 850 million people out of poverty.17 With the rapid economic growth, China has made great efforts to achieve UHC. For example, China has devoted increased public funding to health—the largest increase among Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa countries.18 China has almost achieved all of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) by 2015, making a major contribution to the achievement of the MDGs globally, and is now moving towards SDGs to achieve UHC by 2030.19Table 1 illustrates a summary of key socioeconomic and health indicators in the country from 1990 to 2017, as well as the comparable data in the other Emerging 7 (E7) countries (India, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Indonesia and Turkey) in 2017. China has experienced remarkable improvements in economic conditions, human development and health outcomes, such as life expectancy and mortality. Compared with other E7 countries, China is at a relatively good level in both its economy and population health.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic and health indicators for China and other E7 countries

| China | India | Brazil | Mexico | Russia | Indonesia | Turkey | ||||

| 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2017 | 2017 | ||||||

| GNI per capita, PPP (current international $)* | 990 | 2900 | 9290 | 16 800 | 6950 | 15 270 | 18 210 | 25 120 | 11 910 | 27 640 |

| GDP growth (annual %)* | 3.91 | 8.49 | 10.64 | 6.90 | 7.17 | 1.06 | 2.04 | 1.65 | 5.07 | 7.44 |

| Human Development Index (HDI)† | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.79 |

| Life expectancy at birth, total (years)* | 69.3 | 72.0 | 75.2 | 76.4 | 68.8 | 75.7 | 77.3 | 72.1 | 69.4 | 76.0 |

| Maternal mortality ratio (modelled estimate, per 100 000 live births)*‡ | 97 | 59 | 36 | 29 | 145 | 60 | 33 | 17 | 177 | 17 |

| Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1000 live births)§ | 53.8 | 36.8 | 15.8 | 9.3 | 39.4 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 7.6 | 25.4 | 11.6 |

| Mortality rate, neonatal (per 1000 live births)§ | 29.5 | 21.4 | 8.4 | 4.7 | 24 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 12.4 | 5.9 |

The E7 (short for ‘Emerging 7’) is the seven countries, China, India, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, Indonesia and Turkey, grouped together because of their major emerging economies (cited in Wikipedia).

*Source: The World Bank.

†Source: United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

‡Source: WHO.

§Source: UNICEF.

GDP, gross domestic product; GNI, gross national income; PPP, purchasing power parity.

A review of the reform progress

Since the founding of the PRC in 1949, China has experienced dramatic changes in its healthcare system. Like many other countries, China’s healthcare reform has also undergone a difficult exploratory process. Therefore, it is necessary to briefly review the progress of reform of the healthcare system over the past 70 years. We divide the progress of China’s healthcare reform into three stages.

Stage 1: 30 years after the founding of People’s Republic of China (1949–1979)

At the founding of PRC, with a weak foundation, the state developed a centrally planned socialist system, emphasising public ownership and welfare, mass-based collectivism and egalitarianism.20 In the health sector, the government managed a centrally directed health delivery system, and defined four principles to guide health and medical work: (1) serve the workers, peasants and soldiers; (2) put prevention first, in particular through the Patriotic Health Campaigns; (3) integrate traditional Chinese medicine with Western medicine; and (4) combine health work with mass movements.21 22 These principles of healthcare delivery reform contributed to rapid improvement in the health of the population,23 creating some reform models (eg, ‘Barefoot Doctors’,24 ‘Cooperative Medical System’25 and ‘three-tier health service delivery system’) that were highly valued by the WHO.26 During this period, despite a shortage of healthcare resources, China’s healthcare system achieved almost universal access to healthcare and preventive services, producing impressive health gains—for example, dramatically increased life expectancy and decreased infant mortality.27

Stage 2: 30 years after the ‘reform and opening up’ policy (1979–2009)

Beginning in 1978, China began its ‘reform and opening-up’ policy, ushering in a socialist market economy that encouraged a free market and focused on economic growth. This led to a fundamental transformation of the Chinese healthcare system and had a profound impact.28 29 With privatisation and marketisation, the changes in the healthcare system included: a shift from public financing to private sources; a reorganisation of public hospitals and clinics into commercial enterprises; decentralising healthcare governance to local governments; and a pricing policy that enabled facilities to gain profits.30 31 These changes helped expand healthcare resources and improve medical technology and equipment, but also posed many problems (eg, reduced government expenditure on healthcare, less emphasis on rural areas and public health, and overutilisation of unnecessary or expensive care),32–34 resulting in a series of adverse effects, such as increased disparities between rural and urban residents, a decline in public health, rising healthcare costs and sharp decreases in insurance coverage.23 31 35 In 2003, the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic revealed weaknesses in China’s health system and focused a domestic and international spotlight on those weaknesses.36 This wake-up call opened a window of opportunity for a new round of healthcare reform.

Stage 3: the latest round of healthcare reform (2009 to present)

With the policy goals of achieving a ‘harmonious society’ as a national priority, the Chinese government launched a new round of healthcare reform in 2009.37 It is an unprecedented health system transformation towards UHC, aiming to provide universal coverage of basic healthcare by the end of 2020.38 39 Following extensive interagency consultation and public debates, this launch emphasised a return to government-led, people-centred healthcare and healthcare as a public good. The latest round of healthcare reform adopted the ‘best fit’ with the existing institutional and policy frameworks towards achieving UHC by an incremental approach (step by step), which was recommended by the WHO team.40

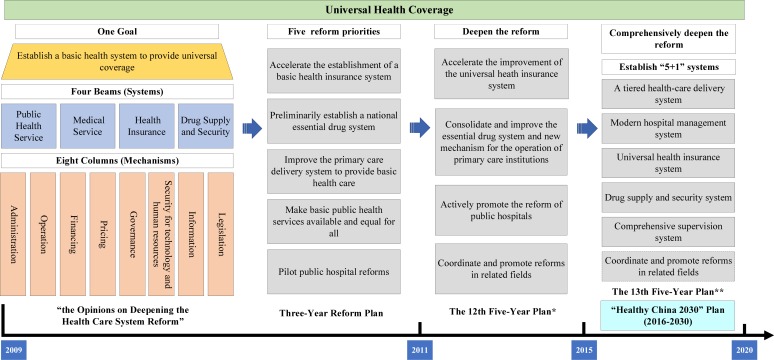

The ‘Opinions on Deepening the Health Care System Reform’ that were promulgated by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the State Council marked the start of China’s new healthcare reform.41 The comprehensive reform plan can be summarised as ‘one goal, four beams, and eight columns’ (figure 1).42 43 Under the goal of achieving UHC, China concentrated on establishing the four systems (ie, public health service system, medical service system, health insurance system, and drug supply and security system), based on the eight functional mechanisms that could provide essential supports. Accordingly, three sequential phases of healthcare reform plans were to be carried out to achieve the overall goal by 2020: the 2009–2011 phase, the 2012–2015 phase and the 2016–2020 phase (figure 1).31 44

Figure 1.

Overall framework and road map of the new round of healthcare reform. *12th Five-Year Plan on deepening the medical system reform. **13th Five-Year Plan on deepening the medical system reform.

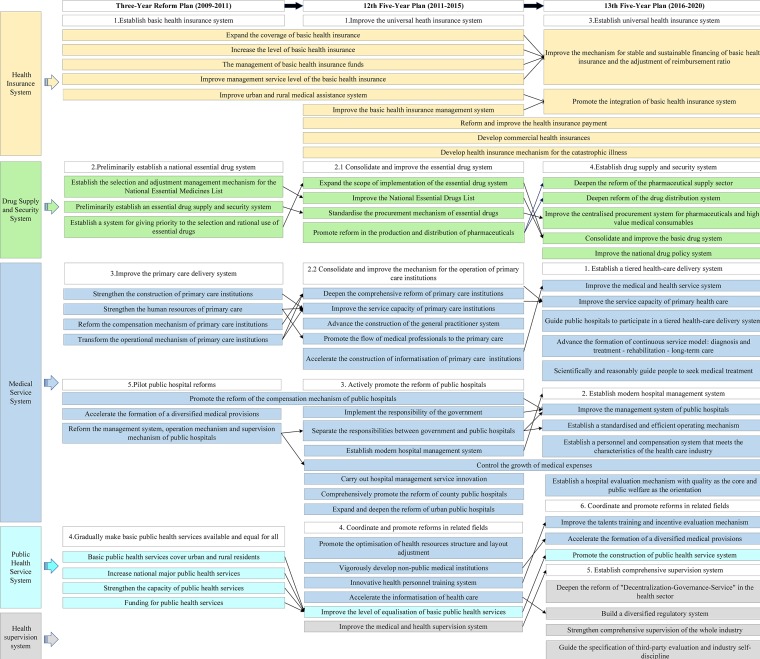

The 2009–2011 phase

The first 3-year reform plan laid a foundation for the 2020 goal. There were five reform priorities: (1) accelerating the establishment of a basic health insurance system; (2) establishing a preliminary national essential drug system; (3) improving the primary care delivery system to provide basic healthcare; (4) making basic public health services (BPHS) available and equal for all; and (5) piloting public hospital reforms.45 46 Reforms during this first phase focused on strengthening primary care. This phase of reform obtained positive evaluations and was confirmed to be heading in the right direction by WHO and others.12 47 48

The 2012–2015 phase

The second phase of healthcare reform, China’s ‘12th Five-Year Plan’, continued in the same general direction.49 The reforms were promoted and deepened during this period, and clarified three tasks: (1) basic health insurance for all; (2) consolidation and improvement of the essential drug system; and (3) reform of public hospitals. The focus of reform gradually shifted from primary care to the public hospitals, especially county public hospitals. The county public hospitals lead the reform of public hospitals through subsidising medical services with profit from drug sales, and comprehensively promoting the reform of the management system, compensation mechanism, personnel distribution, procurement mechanism and price mechanism.

The 2016–2020 phase

Following the reform tasks specified at the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the CPC in 2013, the ‘13th Five-Year Plan on deepening the health care system reform’ marked the beginning of the third phase, a comprehensive drive for deeper reform.50 The reform of this phase focuses on the transitions from: (1) laying a solid foundation to improving quality; (2) framework formation to system construction; and (3) single-area breakthroughs to system integration and comprehensive promotion. ‘Tripartite System Reform (TSR)’, which refers to the linkage reform of the medical care, medical insurance and pharmaceutical industry, became the basic principle for comprehensively deepening the healthcare reform. It is noteworthy that this phase of reform is guided by the ‘Healthy China 2030’ strategy, which emphasises ensuring population health for all individuals across the life course and integrated Health in All Policies.51 52

Figure 2 illustrates the priorities and relationship among the three healthcare reform plans.

Figure 2.

The priorities and relationship among the three healthcare reform plans.

Main reform initiatives and achievements of the past decade

Health insurance system

Reforming the health insurance system is essential and critical since it has served as the major source of financing for the healthcare delivery system. Basic health insurance in China, including the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS) and the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI), laid the foundation for universal insurance coverage. Priority was given to expanding the scope and health service package of the basic insurance coverage, improving provider payment mechanisms, as well as increasing the financing level, fiscal subsidies and reimbursement rates. To improve equity in access to healthcare between rural and urban areas and efficiency in operation of the schemes,53 the Chinese government consolidated the fragmented health insurance schemes by merging NRCMS and URBMI into the Urban and Rural Resident Medical Insurance in 2016,54 and then established the National Healthcare Security Administration in 2018 to implement unified management for these insurance schemes. In addition, the government launched Medical Financial Assistance in 2003 and Catastrophic Medical Insurance in 2012 as supplementary medical insurance to provide funds for patients with poverty and catastrophic illness.55 The moves, parts of ‘Health Poverty Alleviation (HPA)’ (a critical element of the national Poverty Alleviation Project), are significant steps towards ‘Healthy China’ and UHC, protecting people with low incomes from impoverishment due to exorbitant healthcare costs, and breaking the cycle of poverty and illness.55 The payment reform is being implemented to modify the behaviour of providers and to control the unreasonable growth of medical expenses—replacing fee-for-service payment with comprehensive payment methods based on disease category.56

Drug supply and security system

As the base of drug supply and security system, the national essential medicines system reform is comprehensive and includes but is not limited to the following: the selection, production and distribution of essential medicines; quality assurance; reasonable pricing; tendering and procurement; a zero mark-up policy on sales; rational use and reimbursement; and monitoring and evaluation.57 The government issued a revision of the National Essential Medicines List (NEML) in 2009 including a list of 307 essential medicines, and constantly expands the list to fully meet the needs of basic healthcare.58 These on-list medicines should be available at all primary care institutions. To improve access to medicines, China boosted the research and development of generic drugs, and required the evaluation of generics to prove they are equivalent to the originator products in terms of quality and efficacy.59 A ‘two invoice policy’ tendering system was developed to avoid higher mark-up and reduce circulation during the process of distribution.60 All medicines in the NEML are included in health insurance reimbursement lists, which are reimbursed at higher rates compared with non-essential medicines.

Medical service system

Establishing a strong primary care delivery system is an ongoing priority in China. The government has increased investment in primary care, with initiatives that include strengthening the infrastructure of primary healthcare (PHC) facilities, expanding human resources for primary care through incentives and supporting projects, establishing a general practitioner system61 and improving the capacity of PHC personnel through training and education, such as general practice training and continuous medical education programmes. Public hospital reforms focus on removing drug mark-ups as a source of financing, and rationalising medical service pricing (eg, improving the price of medical services that can reflect the value of medical staffs’ technical services, and piloting the removal of medical consumable mark-ups). Additionally, the priority task is establishing a tiered healthcare delivery system by developing healthcare alliances to improve intersectoral coordination and integration62 and providing family practitioners contracted services.63 The development of private hospitals is encouraged to increase the supply of healthcare resources. Further, telemedicine is promoted to improve the delivery of services to people living in remote and poverty areas.

Public health service system

The ‘equalization of basic public health services’ policy implemented the national BPHS programme and the crucial public health service (CPHS) programme. It aims to reduce major health risk factors, prevent and control major communicable diseases and chronic diseases and improve response to public health emergencies.64 This policy seeks to achieve universal availability and promote a more equitable provision of basic health services to all urban and rural citizens. The BPHS set out the minimum services for all citizens, including health management and monitoring. The service package can be expanded by local governments according to local public health issues and financial affordability. CPHS seeks to fight important infectious diseases (eg, prevention and control of tuberculosis, AIDS and bilharziasis) and meet the needs of vulnerable groups (eg, breast and cervical cancer screening for rural women, cataract surgery for low-income patients).65 With a focus on public health and prevention, the State Council announced a series of 15 recommended actions to achieve ‘Healthy China 2030’ on 15 July 2019, which include ‘intervening in health influencing factors, protecting full-life-cycle health, and preventing and controlling major diseases’.66

During the past 10 years since the latest round of healthcare reform, China made steady progress in achieving the reform goals and UHC. Table 2 showed the summary of the main reform initiatives and achievements.

Table 2.

Summary of the main reform initiatives and achievements, 2009 to present

| Reform areas | Main reform initiatives | Achievements |

| Health insurance system | Expanding the population coverage of the basic health insurance schemes. | More than 95% of the population covered by social health insurance schemes in 2018. |

| Extending the health service package of the basic health insurance schemes. | The number of pharmaceuticals on the drug list was expanded to 2643 in 2019; government subsidies per capita for the URBMI and NRCMS have increased more than fivefold in 2018 compared with 2009. | |

| Developing the MFA for people living in extreme poverty. | In 2018, a total of ¥42.46 billion was spent from medical assistance funds nationwide to subsidise 76.739 million people to participate in basic medical insurance, and 53.61 million people received outpatient and inpatient assistance. | |

| Developing the CMI for those people with catastrophic medical expenditure. | Since 2013, CMI has covered 1.01 billion people in China and benefited more than 11 million people (60% of whom are rural residents), and reimbursement payments have exceeded ¥30 billion.73 | |

| Integrating basic health insurance systems of rural and urban residents: merging NRCMS and URBMI into the URRMI. | Unifying insurance coverage, funding policies, insured treatment, reimbursement catalogues, management of contracted medical institutions and fund management: for example, the number of drugs covered in the insurance drug list is unified to 2643 in 2019, and the per-capita premium is unified to ¥693 in 2018. | |

| Reforming the payment system. | 65% of public hospitals above the second level have carried out reforms of the disease category-based insurance payment in 2017; announcing a list of 30 pilot cities for DRG payment reform in 2019. | |

| Drug supply and security system | Zero mark-up policy on drug sales. | All public hospitals nationwide have removed the medicine mark-ups in 2017. |

| Formulating and expanding the NEML. | Issuing a revision of the NEML in 2009 including a list of 307 essential medicines, and expanding the list to 520 medicines in 2012 and 685 medicines in 2018.58 | |

| Supplying and evaluating the generic drugs. | Publishing the first list of 34 generic drugs on June 2018; as of 28 August 2019, 313 product specifications have passed the generic drug consistency evaluation.74 | |

| Reforming the drug tendering and procurement system. | 11 pilot provinces and 200 pilot cities have implemented the ‘two invoice policy’ tendering system by the end of 2017; the drug procurement costs of the corresponding varieties in 11 pilot cities fell from ¥7.7 billion to ¥1.9 billion, and the cost dropped by 75.3%. | |

| Promoting rational use of essential drugs. | Rates of antibiotic use in inpatient and outpatient care decreased by 50% in selected tertiary hospitals.75 | |

| Medical service system | Increasing investment in the primary healthcare system, including strengthening the infrastructure of PHC facilities. | Government subsidies to PHC institutions have increased substantially: from 2009 to 2017, subsidies as a proportion of total PHC income increased from 12.3% to 32.5%.76 |

| Expanding human resources for primary care through incentives and supporting projects. | Compared with 2012, the total number of primary healthcare workers in 2017 increased by 7.1% to 3.863 million, and the number of general practitioners per 10 000 population increased from 0.8 to 1.8. | |

| Developing a tiered service delivery system by establishing HCAs and providing family practitioners contracted services. | Tiered healthcare system started by 95% of municipalities by the end of 2017; all 2134 tertiary public hospitals in China participated in the establishment of HCAs in 2018. | |

| Improving pricing policies: removing mark-up of drugs as a source of finance for all public hospitals, increasing the price of medical services that can reflect the value of medical staffs’ technical services. | In 2017, 27.5% of the medical revenue of public hospitals reflected the value of technical services of medical staff (medical service income), an increase of 2.8 percentage points over the previous year. Drugs and consumables accounted for 48.0% of the total revenue, 4.2 percentage points lower than the previous year. Among them, the proportion of medicines dropped to 34.7%. | |

| Implementing telemedicine to improve the delivery of services to people living in remote and low-income areas. | More than 13 000 medical institutions implemented telemedicine services, which have covered all national poverty counties. | |

| Public health service system | Providing basic public health service package to all people through government subsidies. | Increased government public funding was invested to expand the services (from 9 categories in 2009 to 14 categories in 2017) and availability of the basic public health package to almost everyone; an average of ¥15 was allotted per capita in 2009 and was increased to ¥55 in 2018. |

| Supporting programmes to control the main public health problems. |

Adapted from Meng et al [62]. Data sources are from the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China website, the National Health Commission website and the National Healthcare Security Administration website.

¥7=US$1.

CMI, Catastrophic Medical Insurance; DRG, diagnosis-related group; HCA, healthcare alliance; MFA, Medical Financial Assistance; NEML, National Essential Medicines List; NRCMS, New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme; PHC, primary healthcare; URBMI, Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance; URRMI, Urban and Rural Resident Medical Insurance.

Lessons from China’s experience

Achieving UHC is a tough and long-term task that is not unique to China and confronts many other countries. When pursuing UHC, China adopted the general strategies recommended by WHO, and also developed a pathway with Chinese characteristics through healthcare reform. The experience from China may provide invaluable lessons for other countries.

First, continued political support is the most important enabling condition for achieving UHC. Efforts through national-level initiatives of different governments show that the political will to drive better healthcare is crucial, such as the 2017 National Health Policy in India and Rwanda’s Vision 2020.67 China’s commitment to UHC remains unchanged since the healthcare reform in 2009, and progress through three phases step by step focusing on the overall goal. CPC and governments at all levels have shown clear political willingness to reach the goal by 2030, making UHC achievement a more country-led process. In 2016, President Xi Jinping announced ‘Healthy China 2030 Blueprint’, a national long-term strategy in health sector that sets ambitious targets for China.

Second, increasing health financing is necessary, and the investment from both government and private sectors is considered. At the initial phase of the healthcare reform, on the basis of limited financial fund, Chinese government increased investment in healthcare infrastructure and greatly increased the coverage of health insurances, achieving the universal coverage maximally. After years of exploration during the reform process, it was realised that China should strike a proper balance between the government and the market—play the government’s leading role in providing basic health services, and at the same time, introduce appropriate competition mechanisms to energise the market in non-basic health services, encouraging the private sector to provide multilevel and diversified medical services.

Third, a strong PHC system should be regarded as a core component in realising UHC. Along with the new Declaration of Astana, PHC for health as a global priority is the pathway to reach the SDGs and UHC.68 In the early days, some experience in PHC in China demonstrated that ‘health for all’ is a practical possibility, for example, the ‘Patriotic Health Campaign’ and ‘Barefoot Doctors’.69 The ‘Patriotic Health Campaign’ encouraged everyone to participate in public health activities, and aimed to improve sanitation, hygiene, health education, as well as combat infectious diseases.70 Engagement of civil society is necessary to promote UHC. The ‘Barefoot Doctors’ model used limited medical resources to provide common disease diagnosis and prevention services to a large rural population. However, the Chinese healthcare system created adverse consequences after market-based reforms, in part due to a weakening of support for PHC.71 Today, recognising the importance of revamping its PHC system, the Chinese government has made PHC a priority in its ‘Healthy China 2030’ strategy.

In addition to these general lessons, there are also some lessons with Chinese characteristics, providing reform experiences for other countries: (1) China’s health reforms are usually piloted and then rolled out nationwide, such as the public hospital reform; or the reform started from the grass level and then refined for the nation, such as the Sanming model.72 (2) In the latest phase of reform, China is paying more attention to the systemic and linkage reform (ie, TSR). This innovative strategy can help promote the dynamic balance among medical care, medical insurance and medicine, and construct a coordinating healthcare system to achieve UHC.

Conclusion

A strength of our study was that we systematically and comprehensively assessed healthcare reform in the past decade moving towards UHC in China, including evolution, initiatives and achievements. The lessons learnt from China could help other nations improve UHC in sustainable and adaptive ways, including continued political support, increased health financing and a strong PHC system as basis. The experience of the rapid development of UHC in China can provide a valuable mode for countries (mainly LMICs) planning their own path further on in the UHC journey.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

WT and ZZ contributed equally.

Contributors: WT and ZZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, collected and analysed the data, produced the tables and figures and interpreted the results. HD contributed to the paper’s formulation. WT and BL did the literature search and review. LC was involved in editing each draft. DY, JW and RZ provided comments and suggestions in revisions of the paper. WL designed the study and set the research direction. GFK critically revised the paper and provided overall guidance. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 71874115) and China Scholarship Council (CSC; No 201806240304).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Verrecchia R, Thompson R, Yates R. Universal health coverage and public health: a truly sustainable approach. Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e10–11. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30264-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization WH The world health report 2013: research for universal health coverage, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bump J, Cashin C, et al. , Participants at the Bellagio Workshop on Implementing Pro-Poor Universal Health Coverage . Implementing pro-poor universal health coverage. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e14–16. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00274-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tichenor M, Sridhar D. Universal health coverage, health systems strengthening, and the world bank. BMJ 2017;358:j3347 10.1136/bmj.j3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horton R. Offline: WHO-a roadmap to renewal? Lancet 2017;390:2230 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32904-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Lancet Public Health Universal health coverage: realistic and achievable? Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e1 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30268-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atun R, Aydın S, Chakraborty S, et al. . Universal health coverage in turkey: enhancement of equity. Lancet 2013;382:65–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61051-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agustina R, Dartanto T, Sitompul R, et al. . Universal health coverage in Indonesia: concept, progress, and challenges. Lancet 2019;393:75–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31647-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tangcharoensathien V, Witthayapipopsakul W, Panichkriangkrai W, et al. . Health systems development in Thailand: a solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet 2018;391:1205–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30198-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarker AR, Sultana M, Mahumud RA. Cooperative societies: a sustainable platform for promoting universal health coverage in Bangladesh. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000052 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang L, Langenbrunner JC. The long March to universal coverage: lessons from China. universal health coverage studies series (UNICO) No.9. Washington DC: The World Bank, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yip WC-M, Hsiao WC, Chen W, et al. . Early appraisal of China's huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet 2012;379:833–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng Q, Xu L. Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in China. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001694 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNFPA World population Dashboard-China, 2019. Available: https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/CN [Accessed 6 May 2019].

- 15.China: human development indicators, 2018. Available: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/CHN# [Accessed 7 Aug 2019].

- 16.Brown RE, Piriz DG, Liu Y, et al. . Reforming health care in China: historical, economic and comparative perspectives, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bank W. The world bank in China, 2019. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china [Accessed 9 May 2019].

- 18.Marten R, McIntyre D, Travassos C, et al. . An assessment of progress towards universal health coverage in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). Lancet 2014;384:2164–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60075-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNDP Report on China's implementation of the millennium development goals (2000-2015); 2015.

- 20.Chen M-S. The Great Reversal: Transformation of Health Care in the People's Republic of China In: Cockerham WC, ed The Blackwell companion to medical sociology, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hesketh T, Wei XZ. Health in China. from MAO to market reform. BMJ 1997;314:1543–5. 10.1136/bmj.314.7093.1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobson A. Health care in China after MAO. Health Care Financ Rev 1981;2:41–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Yi Y. The health sector in China policy and institutional review. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen C. Barefoot doctors in China. Lancet 1974;1:976–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91277-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsiao W, Li M, Zhang S. China's universal health care coverage. towards universal health care in emerging economies. social policy in a development context. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng Q, Yang H, Chen W, et al. . People's Republic of China health system review. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babiarz KS, Eggleston K, Miller G, et al. . An exploration of China's mortality decline under MAO: a provincial analysis, 1950-80. Popul Stud 2015;69:39–56. 10.1080/00324728.2014.972432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsiao WC. Transformation of health care in China. N Engl J Med 1984;310:932–6. 10.1056/NEJM198404053101428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenthal D, Hsiao W, Privatization HW. Privatization and its discontents--the evolving Chinese health care system. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1165–70. 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns LR, Liu GG. China's healthcare system and reform. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsiao W, Li M, Zhang S. China’s Universal Health Care Coverage : Yi I, Towards universal health care in emerging economies: opportunities and challenges. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2017: 239–66. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hillier S, Shen J. Health care systems in transition: people's Republic of China. Part I: an overview of China's health care system. J Public Health Med 1996;18:258–65. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu R, Zou H, Shen C. Health care system reform in China: issues, challenges and options. Citeseer: China Economics and Management Academy, Central University of Finance and Economics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz J, Evans RG, Greenberg S. Evolution of health provision in Pre-SARS China: the changing nature of disease prevention. China Review 2007;7:81–104. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagstaff A, Yip W, Lindelow M, et al. . China's health system and its reform: a review of recent studies. Health Econ 2009;18 Suppl 2:S7–23. 10.1002/hec.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong Z, Phillips MR. Evolution of China's health-care system. Lancet 2008;372:1715–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61351-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng T-M. China’s Latest Health Reforms: A Conversation With Chinese Health Minister Chen Zhu. Health Aff 2008;27:1103–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.How to attain the ambitious goals for health reform in China. Lancet 2015;386:1419 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00452-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potter PB. Dilemmas of access to healthcare in China. China: An International Journal 2010;08:164–79. 10.1142/S0219747210000105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang S, Brixi H, Bekedam H. Advancing universal coverage of healthcare in China: translating political will into policy and practice. Int J Health Plann Manage 2014;29:160–74. 10.1002/hpm.2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Council tCCotCPoCatS Opinions of the central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the state Council on deepening the health care system reform, 2009. Available: http://www.gov.cn/test/2009-04/08/content_1280069.htm [Accessed 17 Jun 2019].

- 42.Freeman CW, Boynton XL. Implementing Health Care Reform Policies in China - Challenges and Opportunities: the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tu J. Health care transformation in contemporary China-Moral experience in a socialist neoliberal Polity. 1st ed Springer Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li L, Fu H. China's health care system reform: progress and prospects. Int J Health Plann Manage 2017;32:240–53. 10.1002/hpm.2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Z. Launch of the health-care reform plan in China. Lancet 2009;373:1322–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60753-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Council S Current major project on health care system reform (2009–2011), 2009. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-04/07/content_1279256.htm [Accessed 19 Jun 2019].

- 47.Cheng T-M. Early results of China's historic health reforms: the view from Minister Chen Zhu. Interview by Tsung-Mei Cheng. Health Aff 2012;31:2536–44. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agency XN. The world Health organization and others made positive evaluations of the phased results of China's health care reform, 2012. Available: http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2012-01/20/content_2050322.htm [Accessed 5 Aug 2019].

- 49.Council S Notice of the state Council on printing and distributing the planning and implementation plan for deepening the health care system reform during the 12th five-year plan period, 2012. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2012-03/21/content_6094.htm [Accessed 22 Jun 2019].

- 50.Council S Notice of the state Council on printing and distributing the 13th five-year plan for deepening the reform of health care system, 2016. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-01/09/content_5158053.htm [Accessed 22 Jun 2019].

- 51.The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the "Outline for the 'Healthy China 2030' Plan", 2016. Available: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm [Accessed 22 Jun 2019].

- 52.Xi J, Jinping X. The governance of China volume 2-Chapter: promote a healthy China. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press Co. Ltd, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meng Q, Fang H, Liu X, et al. . Consolidating the social health insurance schemes in China: towards an equitable and efficient health system. Lancet 2015;386:1484–92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00342-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Council S State Council's opinions on integrating the basic medical insurance system for urban and rural residents, 2016. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-01/12/content_10582.htm [Accessed 13 Jul 2019].

- 55.Fang H, Eggleston K, Hanson K, et al. . Enhancing financial protection under China's social health insurance to achieve universal health coverage. BMJ 2019;365:l2378 10.1136/bmj.l2378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guiding opinions of the general office of the state Council on further deepening the reform of basic medical insurance payment methods, 2017. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/bgt/gwywj2/201707/e552b7fc4b3045c2b7ecacd74f82c05e.shtml [Accessed 28 Aug 2019].

- 57.Hu S. Essential medicine policy in China: pros and cons. J Med Econ 2013;16:289–94. 10.3111/13696998.2012.751176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He J, Tang M, Ye Z, et al. . China issues the National essential medicines list (2018 edition): background, differences from previous editions, and potential issues. Biosci Trends 2018;12:445–9. 10.5582/bst.2018.01265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Opinions of the general office of the state Council on reforming and improving the policy of supply and use of generic drugs, 2018. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2018-04/03/content_5279546.htm [Accessed 25 Aug 2019].

- 60.Barber SL, Huang B, Santoso B, et al. . The reform of the essential medicines system in China: a comprehensive approach to universal coverage. J Glob Health 2013;3:010303 10.7189/jogh.03.010303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.State Council's guidance on establishing a general practitioner systems, 2011. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/gfxwj/201304/b77fdc4825954db68bb436276005bba3.shtml [Accessed August 30 2019].

- 62.Meng Q, Mills A, Wang L, et al. . What can we learn from China's health system reform? BMJ 2019;365:l2349 10.1136/bmj.l2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guidance on the promotion of family practice contract service, 2016. Available: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-06/06/content_5079984.htm [Accessed 21 Aug 2019].

- 64.Mo H. Opinions on promoting the gradual equalization of basic public health services, 2009. Available: http://www.gov.cn/ztzl/ygzt/content_1661065.htm

- 65.Yuan B, Balabanova D, Gao J, et al. . Strengthening public health services to achieve universal health coverage in China. BMJ 2019;365:l2358 10.1136/bmj.l2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.The state Council's opinions on implementing healthy China action, 2019. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-07/15/content_5409492.htm [Accessed 5 Sep 2019].

- 67.Friebel R, Molloy A, Leatherman S, et al. . Achieving high-quality universal health coverage: a perspective from the National health service in England. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000944 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kluge H, Kelley E, Barkley S, et al. . How primary health care can make universal health coverage a reality, ensure healthy lives, and promote wellbeing for all. Lancet 2018;392:1372–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.WHO Primary health Care—The Chinese experience. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 70.An introduction to the Patriotic health work, 2014. Available: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/m/chinahealth/2014-07/15/content_17786163.htm [Accessed 15 Sep 2019].

- 71.Li X, Lu J, Hu S, et al. . The primary health-care system in China. Lancet 2017;390:2584–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fu H, Li L, Li M, et al. . An evaluation of systemic reforms of public hospitals: the Sanming model in China. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:1135–45. 10.1093/heapol/czx058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li H, Jiang L. Catastrophic medical insurance in China. Lancet 2017;390:1724–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32603-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.GBIHealth The latest 313 generic drug evaluation drug summary (2019.8.28), 2019. Available: https://med.sina.com/article_detail_103_2_70915.html [Accessed 7 Sep 2019].

- 75.He P, Sun Q, Shi L, et al. . Rational use of antibiotics in the context of China's health system reform. BMJ 2019;365:l4016 10.1136/bmj.l4016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yip W, Fu H, Chen AT, et al. . 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in universal health coverage. Lancet 2019;394:1192–204. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]