Abstract

Methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MRS) is essential for translation. MRS mutants reduce global translation, which usually increases lifespan in various genetic models. However, we found that MRS inhibited Drosophila reduced lifespan despite of the reduced protein synthesis. Microarray analysis with MRS inhibited Drosophila revealed significant changes in inflammatory and immune response genes. Especially, the expression of anti-microbial peptides (AMPs) genes was reduced. When we measured the expression levels of AMP genes during aging, those were getting increased in the control flies but reduced in MRS inhibition flies age-dependently. Interestingly, in the germ-free condition, the maximum lifespan was increased in MRS inhibition flies compared with that of the conventional condition. These findings suggest that the lifespan of MRS inhibition flies is reduced due to the down-regulated AMPs expression in Drosophila.

Keywords: anti-microbial peptides, Drosophila, lifespan, methionyl-tRNA synthetase

INTRODUCTION

Dietary restriction (DR) extends the lifespan in genetic model organisms including yeast, nematode, fruit fly, and rodents (Liang et al., 2018; Partridge et al., 2005). Extended lifespan by DR occurs by conserved molecular mechanisms: insulin/insulin-like growth factor signaling (IIS) and target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway (Kapahi et al., 2017). IIS pathway regulates development, growth, metabolism, stress responses, fecundity, and lifespan (Broughton and Partridge, 2009; Ikeya et al., 2002). TOR pathway regulates protein translation and metabolism (Bjedov et al., 2010). In the DR condition, the activation of AMPK and Sirt is observed by suppressing IIS and TOR pathway, which contribute to lifespan extension (Fullerton and Steinberg, 2010; Tzatsos and Kandror, 2006; Xiao et al., 2011). Recently, the effect of dietary methionine restriction (MR) on lifespan received attention because MR also extends lifespan in genetic model organisms (Barcena et al., 2018). MR reduces global translation by suppressing TOR-S6K pathway and extends lifespan in worms and mammals (Barcena et al., 2018; Edwards et al., 2015). The inhibition of protein synthesis by the reduction of S6K activation is linked to IIS because TOR-S6K pathway also works as a downstream of IIS. Thus, DR and MR reduce IIS and TOR related protein synthesis, which affects lifespan extension in animals.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARS) are enzymes which attach a particular amino acid to its tRNA counterpart and produce aminoacyl-tRNAs for translation (Lee et al., 2004). ARS are essential enzymes for protein synthesis and cell viability (Han et al., 2012). Besides their roles in translation, ARS mediates diverse non-translational functions such as cell metabolism, tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and innate immunity (Ko et al., 2000; 2001; Park et al., 2005). These non-translational functions are regulated by the multi-tRNA synthetase complex (MSC) (Han et al., 2006). Under various stress conditions, several MSC components including methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MRS) are released from the complex through post-translational modifications (Lee et al., 2016). MRS is a key factor in translation initiation and also play a role in the biogenesis of rRNA, translational fidelity under oxidative stress, and oncogenic transformation in the overexpression condition (Ko et al., 2000; Netzer et al., 2009). Although MRS has evolutionary conserved and significant in translation control, the physiological function of MRS at the organism level is not well studied.

In Drosophila, anti-microbial peptides (AMPs) show defense functions against infections (Lemaitre et al., 1997). Expression of AMPs genes is regulated by NF-κB family transcription factors including Relish (Fabian et al., 2018). In addition, subsets of AMPs are directly regulated by another transcription factor, dFOXO (Becker et al., 2010). The elevated innate immune system is a common feature of aged animals including Drosophila (Zerofsky et al., 2005). Aged flies also show increased transcription levels of AMPs genes (Zerofsky et al., 2005). However, how mRNA expressions of AMPs genes are regulated in aged flies are largely unknown.

Here, we inhibited the expression of the MRS gene using the chemically-induced conditional knock-down system to investigate the lifespan of MRS inhibited Drosophila. When the expression of the MRS gene is inhibited, the lifespan was reduced on the contrary to the expectation. We found that the reduced lifespan of MRS inhibition flies is due to down-regulated AMPs expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila culture and stocks

Flies were maintained at 25˚C on standard cornmeal, yeast, sugar, agar medium (standard medium). w1118, ActinGS-Gal4, and UAS-MRS RNAi were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (USA). For the activation of gene switch system, 20 μg/ml mifepristone (RU486; Sigma, USA) was mixed in the standard medium.

Generation of germ-free Drosophila melanogaster and fly husbandry

Germ-free flies were generated by bleaching the embryos. Embryos of ActinGS-Gal4 and UAS-MRS RNAi were collected for 12 h and then dechorionated for 50 s in 5% sodium hypochlorite solution (Wako Chemicals, USA), rinsed for 50 s in 70% ethanol, and washed for 1 min in sterile distilled water. Sterile embryos were transferred into sterile standard cornmeal-sugar-yeast (CSY) food bottles on a clean bench. Eggs in a germ-free condition were passed through repeated generations and became second-generation flies. All germ-free flies were maintained on a clean bench and were transferred to fresh food every two days. The germ-free conditions were confirmed by plating fly homogenate on plate count agar (PCA; Neogen Corporation, USA), and by 16S rRNA gene PCR with a bacterial 16S rRNA universal primers (27F and 1492R) provided by Macrogen. CSY media were used during culture and rearing of the flies. To produce the sterile CSY diet, CSY medium (5.2% cornmeal, 11% sugar, 2.5% instant yeast, 0.5% propionic acid, 0.04% methyl-4-hydroxybenzoate, 1% agar) was autoclaved at 120˚C for 20 min, and all bottles containing food were exposed to UV light for 20 min on a clean bench.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

From the wholebody of 10 adult flies, total RNA was isolated with the easy-BLUE reagent (iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea). After treating the RNA samples with RNase-free DNase I (Takara, Japan), cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, USA). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed with the CFX connect (Bio-Rad, USA) using the Syber Green PCR Core reagents (Toyobo, Japan). Each experiment was performed at least three times and the comparative cycle threshold was used to present a fold change for each specific mRNA after normalizing to rp49 levels. The primers used in the qPCR analyses are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Microarray analysis

For each RNA, the synthesis of target cRNA probes and hybridization were performed using Agilent’s Low Input QuickAmp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The hybridization images were analyzed by Agilent DNA microarray Scanner (Agilent Technologies) and the data quantification was performed using Agilent Feature Extraction software 10.7 (Agilent Technologies). Functional annotation of genes was performed according to Gene Ontology TM Consortium (http://www.geneontology.org/index.html) by GeneSpring GX 7.3.1.

SUnSET assay

Surface sensing of translation (SUnSET) was performed (Schmidt et al., 2009) on the control (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU–) and MRS inhibition flies (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU+). Whole body of each genotype flies were incubated in Shields and Sang M3 insect medium (cat. #S8398; Sigma) containing 2 μg/ml puromycin (cat. #P8833; Sigma) for 3 h at 25˚C. After puromycin incubation, Western blotting was performed to confirm the levels of puromycin incorporation with actin as a loading control. Mouse anti-Puromycin primary antibody (cat. #MABE343; Millipore, USA) was used at 1:1,000 dilution. Each sample was loaded in parallel on two gels/membranes so that actin band could be distinguished from puromycin containing peptides.

Western blot

Total protein was isolated from adult bodies of flies with the PROPREP protein extraction buffer (iNtRON Biotechnology) or RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling, USA). The fly proteins (30 μg) was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membranes was blocked for 2 h in TBST buffer containing 5% non-fat milk and incubated them overnight at 4˚C in TBST buffer containing 5% bovine serum albumin with primary antibodies. After the incubation with secondary antibodies and subsequent washes, images of the membranes were digitized using the Fluorchem E (Protein Simple, USA). Then, target proteins versus their internal loading control band intensities were quantified with the Image J software. Following primary and secondary antibodies were used: anti-phospho-S6K (1:1,000; Cell Signaling), anti-puromycin (1:1,000; Millipore), anti-GFP (1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-β-actin for Drosophila (1:1,000; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB], USA), Goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:3,000; Cell Signaling), and Goat anti-mouse IgG (1:3,000; Cell Signaling).

Lifespan assay

Lifespan was measured in adult flies kept in standard medium and RU486 medium. Newly eclosed male adult flies from each genotype were collected and assigned 20 flies per vial in normal fly food and RU486 medium. Flies were transferred and dead flies were recorded every 2 or 3 days.

Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least three times and the data were shown as the mean and error bar (±SEM) using Prism7.02 (GraphPad Software, USA). Student’s t-test was used to compare each group and P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. For lifespan analyses, log-rank tests were performed using the online survival analysis tool OASIS2 (Han et al., 2016).

RESULTS

Protein translation is reduced in MRS inhibited Drosophila

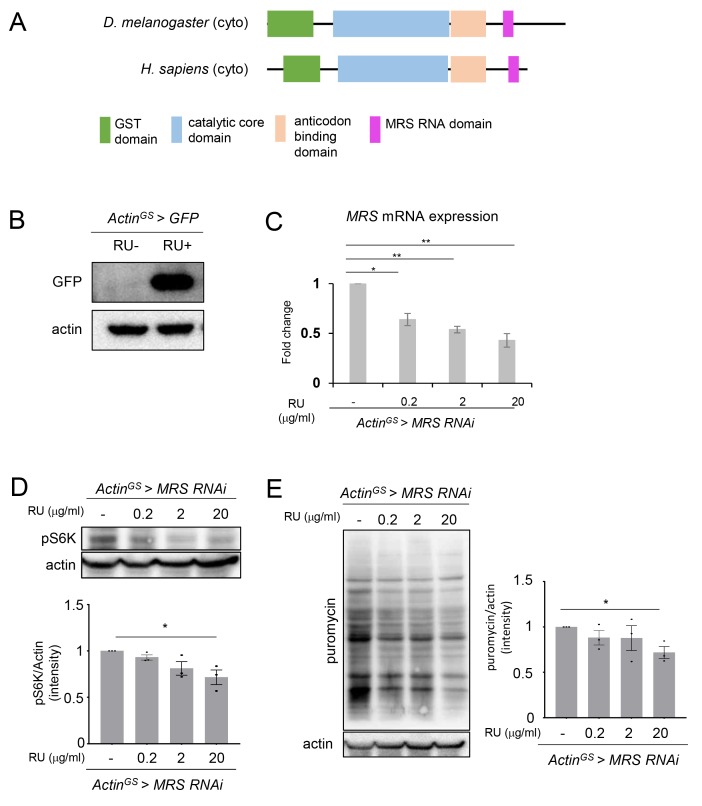

MRS is a key regulator of translation process and an evolutionary conserved enzyme from insect to human. Drosophila MRS is an evolutionary conserved protein with GST domain, catalytic domain, anti-codon binding domain, and MRS RNA domain like those in the human MRS (Fig. 1A). To study the in vivo function of MRS, we used Gene Switch (GS) Gal4/UAS system. To test this system, UAS-GFP flies were crossed with ActinGS-Gal4 (ActinGS > GFP) without RU486 chemical inducer (RU–) and with RU486 (RU+). In the RU+ condition, GFP was strongly expressed (Fig. 1B). To inhibit MRS expression in the whole body of adult flies, UAS-MRS RNAi flies were crossed with ActinGS-Gal4 (ActinGS > MRS RNAi) and RU486 was fed in the adult ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies. The expression level of MRS mRNA in adult ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies was RU dose-dependently decreased compared with RU– control (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Evolutionary conserved domains of Drosophila MRS, the efficacy of GeneSwitch system, and protein translation in MRS inhibition flies.

(A) Evolutionary conserved domains between human MRS and Drosophila MRS. (B) GFP protein level was highly elevated in ActinGS > GFP flies with RU486 20 μg/ml (RU+). (C) MRS mRNA expression was getting reduced in ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies RU dose dependently. (D) Protein translation level marked by the phosphorylated S6K protein was reduced in MRS inhibition flies RU dose dependently. (E) Global translation marked by puromycin incorporation was reduced in MRS inhibition flies RU dose dependently. RU 0.2, RU 2, and RU 20: ActinGS > MRS RNAi with RU486 0.2 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml, 20 μg/ml, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

We examined whether MRS inhibition flies (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU+) reduces protein translation. ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies with RU 20 μg/ml significantly reduced the pS6K level, a protein translation marker, compared with that of the RU– control (Fig. 1D). In the SUnSET assay, a global translational assay, puromycin incorporation level was reduced in ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies with RU 20 μg/ml compared with that of the RU– control (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies with RU 20 μg/ml significantly reduced protein synthesis as expected.

Lifespan is reduced in MRS inhibited Drosophila

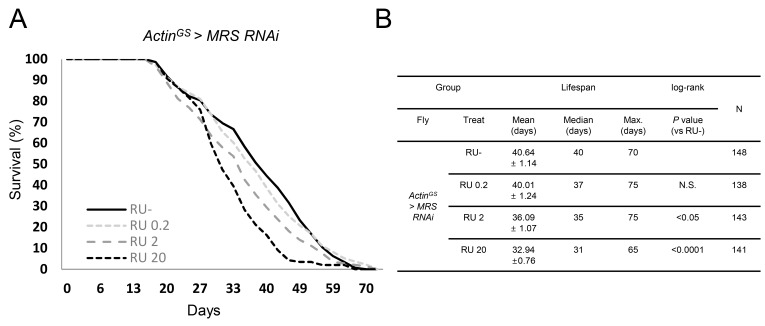

Next, we measured lifespan in ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies. Genetic or chemical inhibition of protein translation extends lifespan from insect to mammals (Bjedov et al., 2010; Kapahi et al., 2004). However, MRS inhibition by ActinGS > MRS RNAi with RU+ reduced median and maximum lifespan dose-dependently compared with those of the RU– control (Fig. 2). These results suggest that MRS inhibition regulates lifespan by factors other than protein translation.

Fig. 2. Lifespan in MRS inhibition flies.

(A) The lifespan of MRS inhibition flies were reduced RU dose dependently. (B) Statistic table of lifespan analysis. RU 0.2, RU 2, and RU 20: ActinGS > MRS RNAi with RU486 0.2 μg/ml, 2 μg/ml, 20 μg/ml.

Inflammation and immune response genes are downregulated in MRS inhibited Drosophila

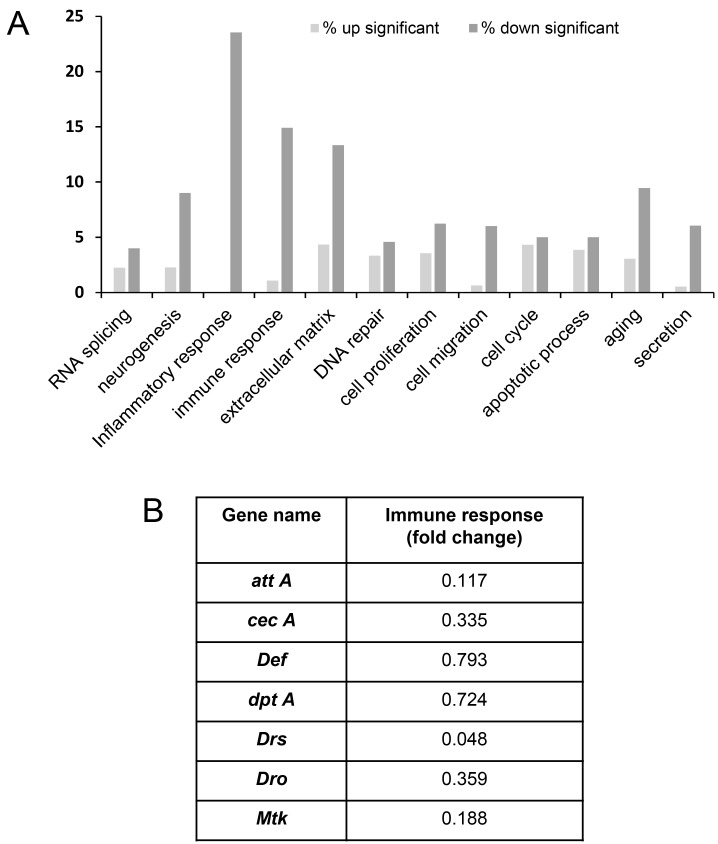

To find factors regulating the lifespan of ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies at the genome level, we performed mRNA microarray analysis using 30 days old ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies. Interestingly, gene ontology classification showed that significantly downregulated genes were in inflammatory and immune response genes (Fig. 3A). AMPs are involved in inflammatory and immune response (Hoffmann, 2003; Stoven et al., 2000). In 30 days old ActinGS > MRS RNAi flies, the expression levels of AMPs (attacin A [att A], cecropin A [cec A], defensin [Def], diptericin A [Dpt A], Drosocin [Drs], Drosomycin [Dro], and Metchnikowin [MTK]) were significantly reduced (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. MRS regulates inflammatory and immune response genes.

(A) Gene ontology graph from the microarray analysis with 30 days old MRS inhibition flies showed that the genes involved in inflammatory and immune responses were changed significantly. (B) Microarray analysis showed that the mRNA expression of AMPs (attA, cecA, Def, DptA, Drs, Dro, and MTK) were down-regulated in 30 days old MRS inhibition flies.

Expressions of AMPs is reduced in aged MRS inhibited Drosophila

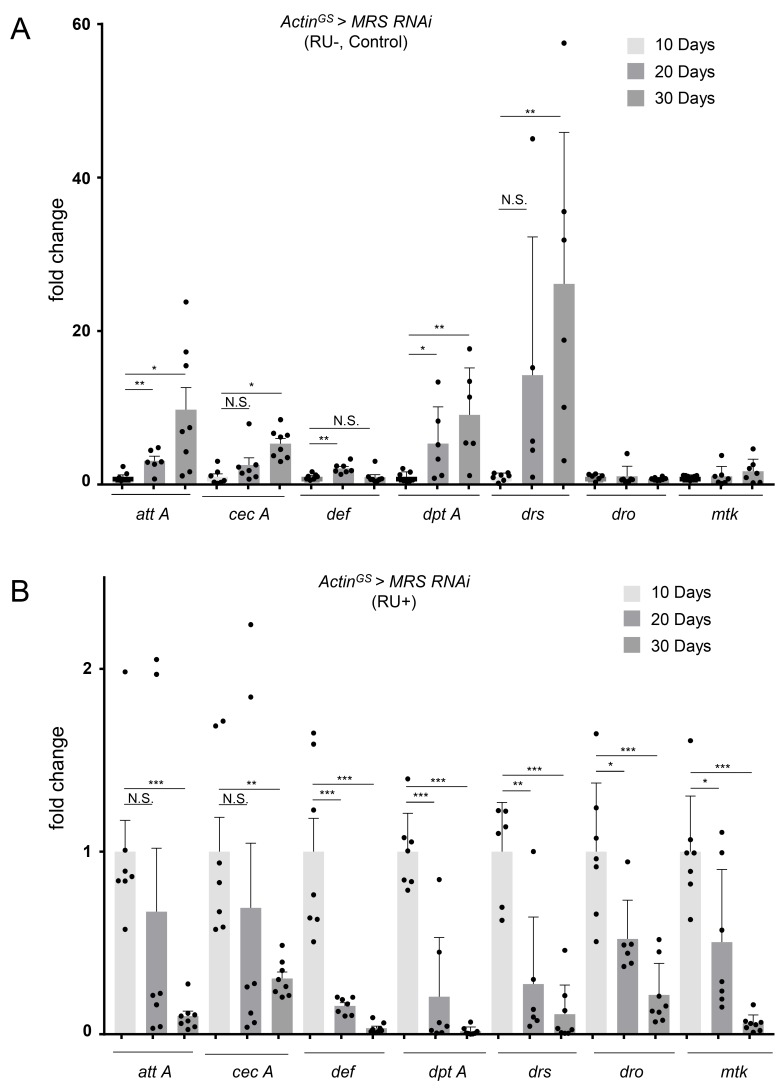

In the previous report, the expression levels of AMPs were increased age-dependently (Zerofsky et al., 2005). We confirmed it in the ActinGS > MRS RNAi RU– control and w– flies using the expression levels of att A, cec A, Def, Dpt A, Drs, Dro, and MTK genes (Fig. 4A). However, in MRS inhibition flies by ActinGS > MRS RNAi RU+, the expression levels of att A, cec A, Def, Dpt A, Drs, Dro, and MTK genes were decreased by aging (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that the reduced lifespan of MRS inhibition flies may relate to the lack of innate immune response by the decreased AMPs expression.

Fig. 4. Expression of AMPs is reduced by aging in MRS inhibition flies.

(A) In the control (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU–), the mRNA expression levels of AMPs (attA, cecA, Def, DptA, Drs, Dro, and MTK) were increased during aging. (B) In MRS inhibition flies (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU+), the mRNA expression levels of AMPs (attA, cecA, Def, DptA, Drs, Dro, and MTK) were reduced by aging. RU+, ActinGS > MRS RNAi with RU486 20 μg/ml. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. N.S., statistically not significant.

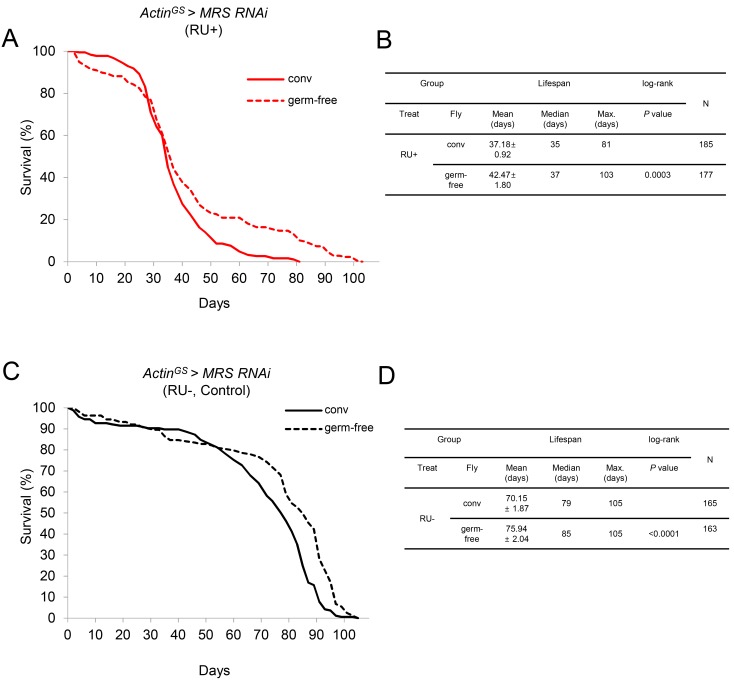

The lifespan of MRS inhibited Drosophila is increased in the germ-free condition

To test whether the reduced lifespan of MRS inhibition flies may relate to the lack of innate immune response, the lifespan of MRS inhibition flies was tested in the germ-free condition. Surprisingly, the maximum lifespan of MRS inhibition flies was increased significantly in the germ-free condition compared with the conventional condition (Figs. 5A and 5B). In the control ActinGS > MRS RNAi RU– flies, the maximum lifespan was not changed in the germ-free condition compared with the conventional condition (Figs. 5C and 5D).

Fig. 5. The lifespan of MRS inhibition flies is increased in the germ-free condition.

(A) The maximum lifespan of MRS inhibition flies was increased in the germ-free condition (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU+; red dotted line) compared with that of the conventional condition (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU+; red solid line). (B) Statistic table of lifespan analysis of Fig. 5A. (C) The maximum lifespan of control flies did not increase in the germ-free condition (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU–, dotted line) compared with that of the conventional condition (ActinGS > MRS RNAi, RU–, solid line). (D) Table of lifespan analysis of Fig. 5C. RU–, ActinGS > MRS RNAi without RU486.

DISCUSSION

It has been known that DR including MR extends the lifespan of animals, which are generally controlled by Insulin signaling and TOR pathway (Kapahi et al., 2017; Min et al., 2008). In this study, we showed an unexpected finding that lifespan was reduced in MRS inhibition flies although the phosphorylation of S6k and global translation level were decreased. We suggest that the reduced lifespan by MRS inhibition is caused by the downregulation of immune response-relating genes. Previous studies reported that aged flies increase AMPs expressions to overcome their immune deficient responses (Zerofsky et al., 2005). The age-dependent diminution of immune response, called immune senescence, is a general phenomenon of aging process (Kuk et al., 2019; Min and Tatar, 2018). Aging is accompanied by chronic inflammation, deterioration of protective gut epithelial barriers, increased pathogen susceptibility, and deregulation of gut microbiota dysbiosis (Min and Tatar, 2018). Consistent with our data of age-dependently elevated expression of AMPs (Fig. 4), the previous report shows that relish and AMPs expression were increased during aging and overexpression of relish and individual AMPs shortened lifespan (Badinloo et al., 2018). MRS inhibition flies seem to mimic immune senescence in the young stage, which results in reduced lifespan.

The microarray data with aged MRS inhibition flies indicate that the expression levels of genes belonging to extracellular matrix, DNA repair, cell proliferation, cell migration, apoptosis, and aging were also changed (Fig. 3A). Deprivation of amino acids, especially the essential amino acids deprivation, exhibits severe loss of cell viability and increased cell death by apoptosis compared with non-essential amino acids deprivation (Simpson et al., 1998). For example, starvation of lysine or histidine, one of the essential amino acids, induces apoptotic cell death through LC3 activation, an autophagy marker. This cell death induces high level of oxidative stress (Eisler et al., 2004). MRS inhibition flies may function as similar to other essential amino acid deprivations in addition to the down-regulated AMPs expression. Therefore, MRS inhibition flies may also induce cell death-mediated oxidative stress, which affects DNA repair, cell proliferation, cell migration, apoptosis, and aging processes.

To address the relationship between MRS and immune responses in lifespan, we tested the lifespan of MRS inhibition flies in the germ-free condition to exclude the effect of commensal bacteria-induced immune system activation. Lifespan studies of wild-type flies in the germ-free condition is controversial. One study showed that the lifespan of wild-type flies in the germ-free and antibiotics medium is reduced than that of the control flies (Brummel et al., 2004), whereas another study reported that the lifespan of wild-type flies in the germ-free condition is extended compared with the conventional condition (Petkau et al., 2014) like our experimental data (Fig. 5B). When we tested the lifespan of MRS inhibition flies in the germ-free condition, the maximum lifespan of MRS inhibition flies increased compared with that of the control (Figs. 5A and 5B). In the germ-free condition, the increased lifespan of MRS inhibition mutants may due to the reduced protein translation.

Recently, MRS has emerged as a target to develop therapeutics for malaria. Malaria is usually occurred by Plasmodium falciparumla infection. MRS of P. falciparum is a new drug candidate. Several malaria MRS inhibitors (REP3123 and REP8839), previously known as bacterial inhibitors, are found by in silico screening (Khan, 2016). Taken together, we suggest a new connection between lifespan and immune response through MRS.

Supplemental Materials

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Drosophila stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA). This work was supported by grants from the KRIBB Research Initiative Program, National Research Council of Science & Technology (CRC-15-04-KIST), and National Research Foundation of Korea (2014M3A6A4075062, 2015R1A5A1009024, and 2019R1A2C2004149).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Badinloo M., Nguyen E., Suh W., Alzahrani F., Castellanos J., Klichko V.I., Orr W.C., Radyuk S.N. Overexpression of antimicrobial peptides contributes to aging through cytotoxic effects in Drosophila tissues. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2018;98:e21464. doi: 10.1002/arch.21464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcena C., Quiros P.M., Durand S., Mayoral P., Rodriguez F., Caravia X.M., Marino G., Garabaya C., Fernandez-Garcia M.T., Kroemer G., et al. Methionine restriction extends lifespan in progeroid mice and alters lipid and bile acid metabolism. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2392–2403. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T., Loch G., Beyer M., Zinke I., Aschenbrenner A.C., Carrera P., Inhester T., Schultze J.L., Hoch M. FOXO-dependent regulation of innate immune homeostasis. Nature. 2010;463:369–373. doi: 10.1038/nature08698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov I., Toivonen J.M., Kerr F., Slack C., Jacobson J., Foley A., Partridge L. Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2010;11:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton S., Partridge L. Insulin/IGF-like signalling, the central nervous system and aging. Biochem. J. 2009;418:1–12. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummel T., Ching A., Seroude L., Simon A.F., Benzer S. Drosophila lifespan enhancement by exogenous bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:12974–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405207101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C., Canfield J., Copes N., Brito A., Rehan M., Lipps D., Brunquell J., Westerheide S.D., Bradshaw P.C. Mechanisms of amino acid-mediated lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Genet. 2015;16:8. doi: 10.1186/s12863-015-0167-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler H., Frohlich K.U., Heidenreich E. Starvation for an essential amino acid induces apoptosis and oxidative stress in yeast. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;300:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian D.K., Garschall K., Klepsatel P., Santos-Matos G., Sucena E., Kapun M., Lemaitre B., Schlotterer C., Arking R., Flatt T. Evolution of longevity improves immunity in Drosophila. Evol. Lett. 2018;2:567–579. doi: 10.1002/evl3.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton M.D., Steinberg G.R. SIRT1 takes a backseat to AMPK in the regulation of insulin sensitivity by resveratrol. Diabetes. 2010;59:551–553. doi: 10.2337/db09-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.M., Jeong S.J., Park M.C., Kim G., Kwon N.H., Kim H.K., Ha S.H., Ryu S.H., Kim S. Leucyl-tRNA synthetase is an intracellular leucine sensor for the mTORC1-signaling pathway. Cell. 2012;149:410–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.M., Lee M.J., Park S.G., Lee S.H., Razin E., Choi E.C., Kim S. Hierarchical network between the components of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex: Implications for complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:38663–38667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605211200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S.K., Lee D., Lee H., Kim D., Son H.G., Yang J.S., Lee S.J.V., Kim S. OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56147–56152. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J.A. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;426:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nature02021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya T., Galic M., Belawat P., Nairz K., Hafen E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P., Kaeberlein M., Hansen M. Dietary restriction and lifespan: lessons from invertebrate models. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017;39:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P., Zid B.M., Harper T., Koslover D., Sapin V., Benzer S. Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. Recent advances in the biology and drug targeting of malaria parasite aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Malar. J. 2016;15:203. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1247-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y.G., Kang Y.S., Kim E.K., Park S.G., Kim S. Nucleolar localization of human methionyl-tRNA synthetase and its role in ribosomal RNA synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:567–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y.G., Park H., Kim T., Lee J.W., Park S.G., Seol W., Kim J.E., Lee W.H., Kim S.H., Park J.E., et al. A cofactor of tRNA synthetase, p43, is secreted to up-regulate proinflammatory genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:23028–23033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk M.U., Kim J.W., Lee Y.S., Cho K.A., Park J.T., Park S.C. Alleviation of senescence via ATM inhibition in accelerated aging models. Mol. Cells. 2019;42:210–217. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2018.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.Y., Lee H.C., Kim H.K., Jang S.Y., Park S.J., Kim Y.H., Kim J.H., Hwang J., Kim J.H., Kim T.H., et al. Infection-specific phosphorylation of glutamyl-prolyl tRNA synthetase induces antiviral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:1252–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.W., Cho B.H., Park S.G., Kim S. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complexes: beyond translation. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:3725–3734. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B., Reichhart J.M., Hoffmann J.A. Drosophila host defense: differential induction of antimicrobial peptide genes after infection by various classes of microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:14614–14619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y.R., Liu C., Lu M.Y., Dong Q.Y., Wang Z.M., Wang Z.R., Xiong W.X., Zhang N.N., Zhou J.W., Liu Q.F., et al. Calorie restriction is the most reasonable anti-ageing intervention: a meta-analysis of survival curves. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5779. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24146-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min K.J., Tatar M. Unraveling the molecular mechanism of immunosenescence in Drosophila. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:E2472. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min K.J., Yamamoto R., Buch S., Pankratz M., Tatar M. Drosophila lifespan control by dietary restriction independent of insulin-like signaling. Aging Cell. 2008;7:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer N., Goodenbour J.M., David A., Dittmar K.A., Jones R.B., Schneider J.R., Boone D., Eves E.M., Rosner M.R., Gibbs J.S., et al. Innate immune and chemically triggered oxidative stress modifies translational fidelity. Nature. 2009;462:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature08576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.G., Kim H.J., Min Y.H., Choi E.C., Shin Y.K., Park B.J., Lee S.W., Kim S. Human lysyl-tRNA synthetase is secreted to trigger proinflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:6356–6361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500226102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L., Piper M.D., Mair W. Dietary restriction in Drosophila. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2005;126:938–950. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkau K., Parsons B.D., Duggal A., Foley E. A deregulated intestinal cell cycle program disrupts tissue homeostasis without affecting longevity in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:28719–28729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.578708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt E.K., Clavarino G., Ceppi M., Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:275–277. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson N.H., Singh R.P., Perani A., Goldenzon C., Al-Rubeai M. In hybridoma cultures, deprivation of any single amino acid leads to apoptotic death, which is suppressed by the expression of the bcl-2 gene. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998;59:90–98. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980705)59:1<90::AID-BIT12>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoven S., Ando I., Kadalayil L., Engstrom Y., Hultmark D. Activation of the Drosophila NF-kappaB factor relish by rapid endoproteolytic cleavage. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:347–352. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzatsos A., Kandror K.V. Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:63–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.63-76.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F., Huang Z.Y., Li H.K., Yu J.J., Wang C.X., Chen S.H., Meng Q.S., Cheng Y., Gao X.A., Li J., et al. Leucine deprivation increases hepatic insulin sensitivity via GCN2/mTOR/S6K1 and AMPK pathways. Diabetes. 2011;60:746–756. doi: 10.2337/db10-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerofsky M., Harel E., Silverman N., Tatar M. Aging of the innate immune response in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2005;4:103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2005.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.