Abstract

BACKGROUND

There is a controversy as to whether laparoscopic surgery leads to a poor prognosis compared to the open approach for early gallbladder carcinoma (GBC). We hypothesized that the laparoscopic approach is an alternative for early GBC.

AIM

To identify and evaluate the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of early GBC.

METHODS

A comprehensive search of online databases, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Cochrane libraries, and Web of Science, was performed to identify non-comparative studies reporting the outcomes of laparoscopic surgery and comparative studies involving laparoscopic surgery and open surgery in early GBC from January 2009 to October 2019. A fixed-effects meta-analysis was performed for 1- and 5-year overall survival and postoperative complications, while 3-year overall survival, operation time, blood loss, the number of lymph node dissected, and postoperative hospital stay were analyzed by random-effects models.

RESULTS

The review identified 7 comparative studies and 8 non-comparative studies. 1068 patients (laparoscopic surgery: 613; open surgery: 455) were included in the meta-analysis of 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival with no significant differences observed [(HR = 0.54; 95%CI: 0.29-1.00; I2 = 0.0%; P = 0.051), (HR = 0.75; 95%CI: 0.34-1.65; I2 = 60.7%; P = 0.474), (HR = 0.71; 95%CI: 0.47-1.08; I2 = 49.6%; P = 0.107), respectively]. There were no significant differences in operation time [weighted mean difference (WMD) = 18.69; 95%CI: −19.98-57.36; I2 = 81.4%; P = 0.343], intraoperative blood loss (WMD = −169.14; 95%CI: −377.86-39.57; I2 = 89.5%; P = 0.112), the number of lymph nodes resected (WMD = 0.12; 95%CI: −2.95-3.18; I2 = 73.4%; P = 0.940), and the complication rate (OR = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.30-1.58; I2 = 0.0%; P = 0.377 ) between the two groups, while patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery had a reduced length of hospital stay (WMD = −5.09; 95%CI: −8.74- −1.45; I2 = 91.0%; P= 0.006).

CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis confirms that laparoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible alternative to open surgery with comparable survival and operation-related outcomes for early GBC.

Keywords: Laparoscopic surgery, Open surgery, Early gallbladder carcinoma, Survival, Meta-analysis

Core tip: Several studies have compared the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic surgery and open surgery for early gallbladder carcinoma. This systematic review and meta-analysis, included 7 comparative studies and 8 non-comparative studies, and found that laparoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible alternative to open surgery with comparable 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival and operation-related outcomes for early gallbladder carcinoma. However, more prospective studies should be performed due to the limited sample size and lack of recurrence data.

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is a rare malignancy with an annual incidence of 1.13 per 100000 in the United States, but it is most common in biliary tract malignancies, occupying 80% to 95% of biliary cancers[1,2]. Compared to other digestive organs, the muscle layers of the gallbladder are relatively thin without submucosal layers, resulting in invasion of other organs more easily[3]. Given the poor overall prognosis with a 5-year survival rate ranging from 5% to 20%, it is considered a highly lethal and aggressive disease which depends on the depth and stage of tumor invasion[4]. Approximately 30% of patients have preoperatively suspected GBC, unfortunately, lacking specific clinical manifestations, and the residual 70% are discovered accidentally during laparoscopic cholecystectomy or postoperative pathologic examination, and are termed incidental GBC (IGBC)[4-7].

Surgical resection is a relatively complete cure for GBC. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system[8], for patients with histological stage Tis or T1a, simple cholecystectomy is considered the definitive treatment, while for patients with a histological stage greater than stage T1b, they should be treated by extended/radical cholecystectomy to obtain negative (R0) margins, including removal of adjacent liver parenchyma, resection of the common bile duct, and portal lymphadenectomy[9,10]. Although 30-d mortality following the resection of GBC postoperatively was between 1.7% and 4.2%, 90-d morbidity and mortality were generally not reported[11-13].

Traditionally, open surgery is recommended for patients with suspected GBC pre-operatively. However, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline and Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery guideline do not recommend curative laparoscopic surgery even for patients with early GBC[14,15]. With the development of surgical techniques and new instruments, laparoscopic surgery for GBC has a potential role in disease staging (staging laparoscopy) and radical surgery[16,17]. As a postoperative outcome, wound metastasis after laparoscopic surgery for GBC is the main factor that hinders the widespread use of a minimally invasive, laparoscopic approach in the treatment of GBC[18]. Some controversy regarding laparoscopic surgery for early GBC still exists. This is due to the dissemination of tumorous cells, the difficulty of extended/radical cholecystectomy, and postoperative recurrence[13,17]. However, recent research suggested that laparoscopic surgery has no adverse effects in comparison with the open approach, and advocated the use of the laparoscopic approach for early GBC[12,19-22]. Due to the small number of patients included in previous studies, doubt remains as to whether laparoscopic surgery leads to a poor prognosis compared to the open approach. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to perform a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to identify and evaluate the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of early GBC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search and selection

A comprehensive systematic literature search of MEDLINE (PubMed), Cochrane libraries, and Web of Science from January 2009 to October 2019 was conducted separately by two authors (XF and JSC) to identify non-comparative studies reporting the outcomes of laparoscopic surgery and comparative studies involving laparoscopic surgery and open surgery in gallbladder carcinoma. The search terms used were “gallbladder carcinoma”, “gallbladder cancer”, “GBC” combined with “laparoscopic surgery”, “laparoscopic cholecystectomy”, “LC”, “laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy”, “LRC”, “open surgery”, “open cholecystectomy” with the Boolean operators AND and OR. Additional studies were identified after reviewing the references of included studies.

All the search results were evaluated according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[23]. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Patients pathologically diagnosed with primary gallbladder carcinoma; (2) Studies mainly analyzing laparoscopic surgery; and (3) Studies comparing laparoscopic surgery with open surgery. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Studies not published in English; (2) Articles including abstracts from conferences, commentary articles, letters, and case reports; (3) Patients with other cancers or high-risk diseases such as stroke, coronary heart disease, and so on; and (4) Patients who underwent chemotherapy or radiotherapy preoperatively.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators (MYC and BZ) input data which were extracted from eligible studies in a Microsoft Excel database (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, United States). The primary outcomes of interest were 1-year overall survival, 3-year overall survival, and 5-year overall survival. The secondary outcomes were intraoperative outcomes, perioperative outcomes, and postoperative outcomes, including operation time, intraoperative blood loss, the number of lymph nodes dissected, postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative complications. For quality assessment of the included studies for meta-analysis, the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used[24], which is widely utilized for assessing nonrandomized studies and involves 3 metrics: Patient selection, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of outcomes for cohort or case-control studies. Any disagreement was resolved by another investigator (JSC).

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States). Odds ratio (OR) was used to compare categorical variables, while weighted mean difference (WMD) was utilized to compare continuous variables. Hazard ratio (HR) with 95%CI, a relevant measure for the effects of overall survival and disease-free survival, were estimated using log-rank χ2 statistics, log-rank P values, the given numbers of events, or Kaplan-Meier curves as described by Parmar et al[25] and Williamson et al[26]. The heterogeneity among effect estimates were examined by the Cochran χ2 test and I2. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was defined as I2 statistic > 50%[27]. When I2 < 50%, the fixed-effects model was preferred to the random-effects model, and vice versa when I2 > 50%[28].

RESULTS

Study selection and quality assessment

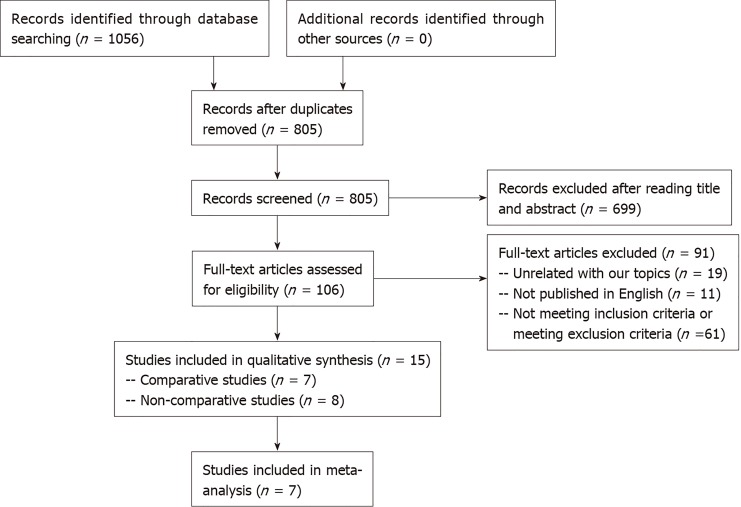

According to a previous search strategy, 1056 records were obtained from the online databases from January 2009 to October 2019. No additional records were identified through other sources. After the removal of duplicates, a total of 805 studies remained. Then 699 records were excluded by the title and abstract screening process. After that, 90 studies were then excluded due to various reasons [unrelated to our topics (n = 18), not published in English (n = 11), not meeting inclusion criteria or meeting exclusion criteria (n =61)]. Finally, 7 comparative studies[13,29-34] and 8 non-comparative studies[21,22,35-40] were included in the systematic review and the former were considered in the meta-analysis (Figure 1). The characteristics and quality evaluation of the 7 included studies for meta-analysis are summarized in Table 1. Moreover, the detailed information including T stage of tumor, survival rate, and recurrence are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

A preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses diagram detailing the search strategy and identification of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included comparative studies

| Ref. | Year | Country | Intervention | Study type | Study period | Propensity-matched | Quality Score |

| Jang et al[33] | 2019 | South Korea | Laparoscopic surgery vs Open surgery | Retro | 2004-2017 | No | 7 |

| Feng et al[32] | 2019 | China | Retro | 2008-2017 | No | 7 | |

| Jang et al[31] | 2016 | South Korea | Retro | 2000-2014 | Yes | 7 | |

| Itano et al[30] | 2015 | Japan | Retro | 2007-2013 | No | 7 | |

| Agarwal et al[13] | 2015 | India | Retro | 2011-2013 | No | 7 | |

| Ha et al[34] | 2014 | South Korea | Retro | 1996-2009 | No | 6 | |

| Goetze et al[29] | 2013 | Germany | Retro | NA | No | 7 |

Retro: Retrospective study; NA: Not available.

Table 2.

Detailed information including T stage of tumor, survival rate, and recurrence in the included comparative studies

| Ref. | Year | Country | Comparison (n) | T stage | Survival | P value | Recurrence | P value | |||

| Jang et al[33] | 2019 | South Korea | Laparoscopic | (55) | T2 | 5-yr OS | 73.1% | 0.116 | 5-yr DFS | 78.0% | 0.017a |

| Open | (44) | 65.7% | 62.4% | ||||||||

| Feng et al[32] | 2019 | China | Laparoscopic | (41) | Tis-T3 | 1/3/5-yr OS | 97.1%/69.4%/51.9% | 0.453 | Postoperative incisional metastasis | 4.9% | NA |

| Open | (61) | 94.7%/64.9%/55.7% | 3.3% | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (9) | Tis | 5-yr OS | 100.0% | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (4) | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (8) | T1b | 5-yr OS | NA | 0.763 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (9) | 87.5% | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (14) | T2 | 5-yr OS | 48.1% | 0.513 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (32) | 64.7% | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (8) | T3 | 5-yr OS | 12.5% | 0.513 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (16) | 16.0% | NA | ||||||||

| Jang et al[31] | 2016 | South Korea | Laparoscopic | (61) | T1 | 5-yr OS | 92.7% | 0.332 | Recurrence | 0.0% | 0.496 |

| Open | (61) | 100.0% | 3.3% | ||||||||

| Itano et al[30] | 2015 | Japan | Laparoscopic | (16) | T2 | 3-yr OS | 100.0% | NA | 3-yr recurrence | 0.0% | NA |

| Open | (14) | 71.4% | 28.6% | ||||||||

| Agarwal et al[13] | 2015 | India | Laparoscopic | (24) | T1-T3 | NA | NA | NA | 18 mo (6–34 mo) | 4.2% | NA |

| Open | (46) | 6.5% | |||||||||

| Ha et al[34] | 2014 | South Korea | Laparoscopic | (25) | T1b/T2 | 1/3/5-yr OS | 94.7%/64.0%/64.0% | 0.607 | NA | NA | NA |

| Open | (150) | 95%/83.4%/76.0% | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (15) | T1b | 1/3/5-yr OS | 91.7%/68.8%/68.8% | 0.649 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (75) | 100.0%/87.6%/ 84.4% | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (10) | T2 | 1/3/5-yr OS | 100.0%/50.0%/50.0% | 0.895 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (75) | 90.0%/79.3%/67.6% | NA | ||||||||

| Goetze et al[29] | 2013 | Germany | Laparoscopic | (492) | T1-T4 | 5-yr OS | 37.0% | < 0.05a | Overall recurrence | 54.9% | > 0.05 |

| Open | (200) | 25.0% | 54.5% | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (95) | T1 | 5-yr OS | 52.0% | > 0.05 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (34) | 57.0% | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (282) | T2 | 5-yr OS | 33.0% | 0.002a | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (81) | 25.0% | NA | ||||||||

| Laparoscopic | (81) | T3 | 5-yr OS | 24.0% | 0.001a | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Open | (59) | 6.0% | NA | ||||||||

OS: Overall survival; DFS: Disease-free survival; NA: Not available.

P < 0.05.

Comparative studies reporting outcomes of laparoscopic vs open surgery

1, 3, 5-year overall survival

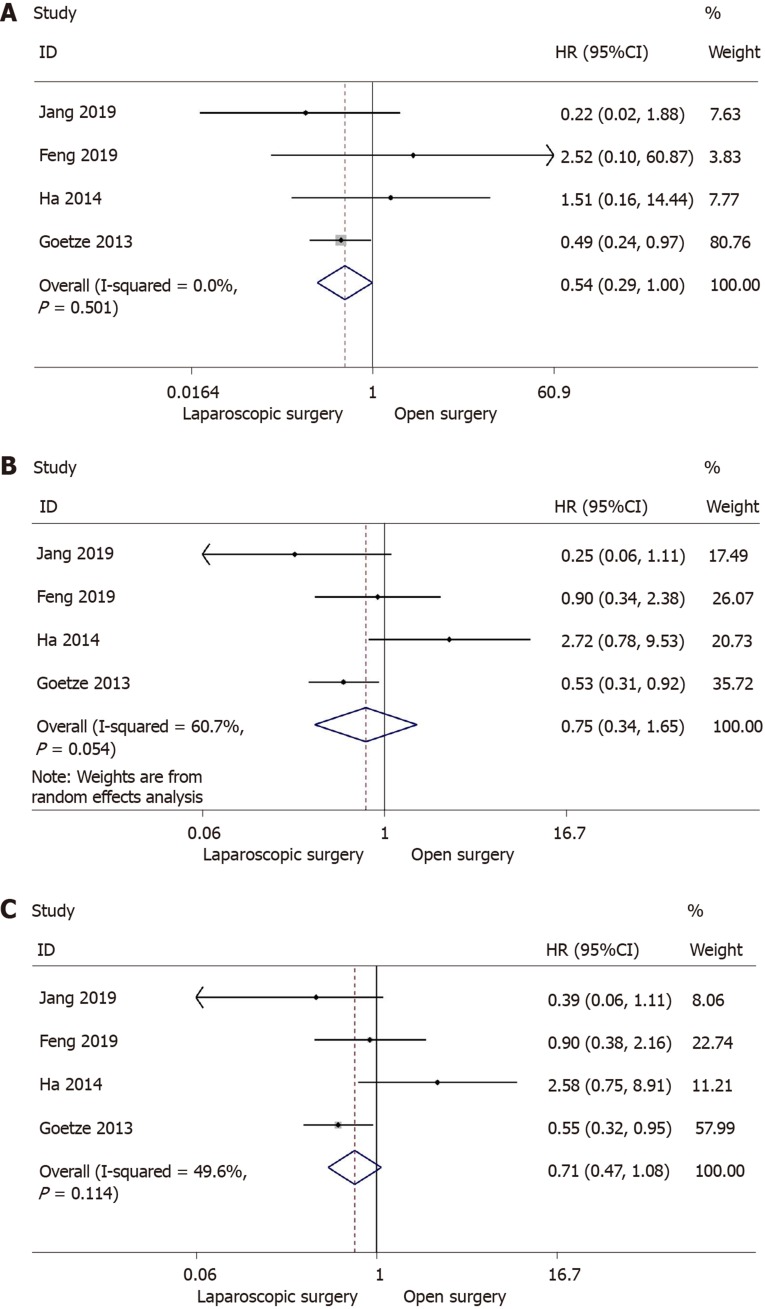

Five retrospective studies[13,30-33] reported 1, 3, and 5-year overall survival, including 1190 patients (laparoscopic surgery = 674, open surgery = 516). However, one of the studies[31] was excluded due to difficulty in calculating the upper 95%CI. Then 1,068 patients (laparoscopic surgery: 613; open surgery: 455) were analyzed in the meta-analysis. Meta-analysis using a fixed-effects model revealed that there was no significant increase in 1-year overall survival following laparoscopic surgery in comparison with open surgery (HR = 0.54; 95%CI: 0.29-1.00; I2 = 0.0%; P = 0.051) (Figure 2A). In addition, no difference was observed in 3-year overall survival following the laparoscopic approach (HR = 0.75; 95%CI: 0.34-1.65; I2 = 60.7%; P = 0.474) (Figure 2B). Following meta-analysis of 5-year overall survival, the fixed-effects model showed no significant difference between the two groups (HR = 0.71; 95%CI: 0.47-1.08; I2 = 49.6%; P = 0.107) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of primary outcome. A: Forest plot and meta-analysis of 1-year overall survival; B: Forest plot and meta-analysis of 3-year overall survival; C: Forest plot and meta-analysis of 5-year overall survival.

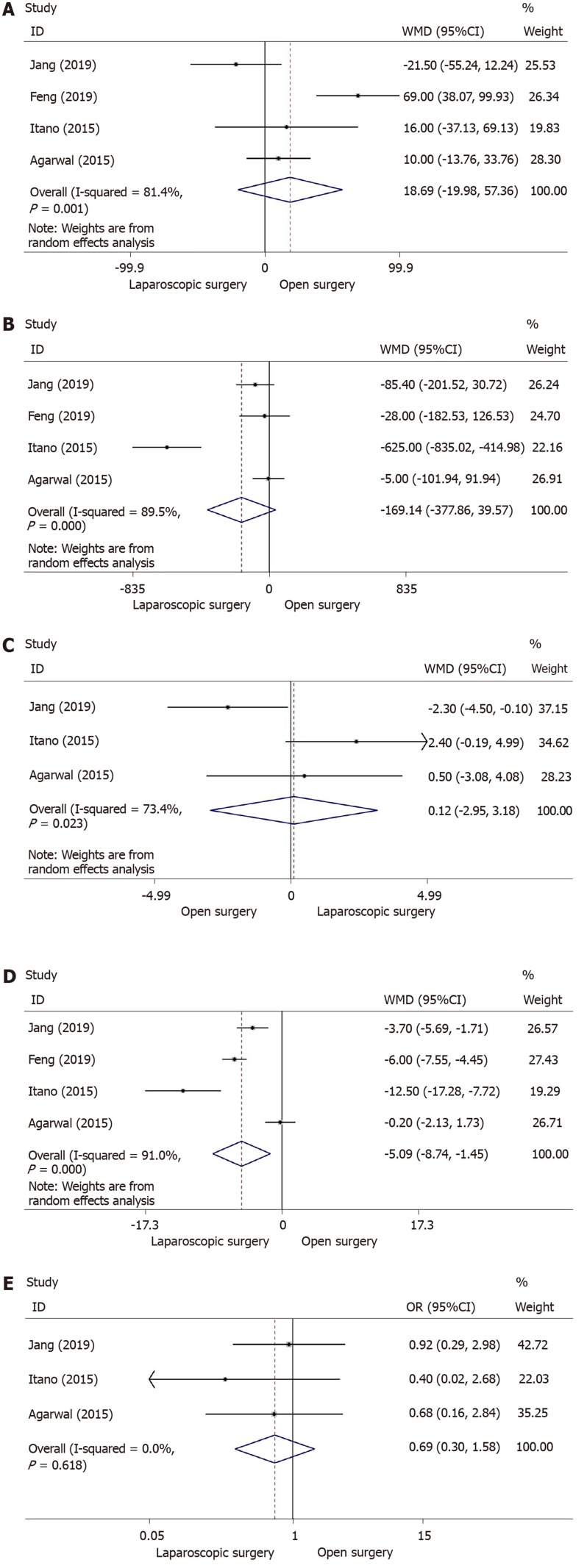

Operation time

Four studies provided information on operation time[13,30,32,33]. The meta-analysis revealed that there was no significant difference in operation time between the laparoscopic approach and open approach (WMD = 18.69; 95%CI: -19.98-57.36; I2 = 81.4%; P = 0.343) (Figure 3A). Due to heterogeneity among the studies, a random-effects model was selected.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of secondary outcomes. A: Forest plot of weighted mean difference (WMD) of operation time; B: Forest plot of WMD of intraoperative blood loss; C: Forest plot of WMD of the number of lymph node dissected; D: Forest plot of WMD of postoperative hospital stay; E: Forest plot of odds ratio of postoperative complications. WMD: Weighted mean difference.

Intraoperative blood loss

Intraoperative blood loss was available in four retrospective studies[13,30,32,33] involving 136 and 165 patients who underwent laparoscopic and open surgery, respectively. Although there was heterogeneity among these studies and meta-analysis using a random-effects model showed no difference (WMD = -169.14; 95%CI: -377.86-39.57; I2 = 89.5%; P = 0.112) (Figure 3B), less blood was lost during the laparoscopic approach for early GBC.

The number of lymph nodes dissected

With regard to the number of lymph nodes resected during surgery, meta-analysis of three studies[13,30,33], including 95 patients in the laparoscopic group (laparoscopic surgery = 95, open surgery = 104) revealed that there was no significance between the two groups (WMD = 0.12; 95%CI: -2.95-3.18; I2 = 73.4%; P = 0.940) (Figure 3C).

Postoperative hospital stay

As heterogeneity was found among four studies[13,30,32,33], we chose a random-effects model to analyze postoperative hospital stay. Patients in the laparoscopic surgery group had a significantly reduced length of hospital stay than the open surgery group (WMD = -5.09; 95%CI: −8.74- −1.45; I2 = 91.0%; P = 0.006) (Figure 3D), which indicated that minimally invasive surgery with the laparoscopic approach for early GBC enhanced recovery after surgery.

Postoperative complications

Three studies[13,30,33] including a total of 199 patients underwent surgery for early GBC (laparoscopic surgery: 95, open surgery: 104). Using a fixed-effects model, the meta-analysis indicated no significant difference in postoperative complications (OR = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.30-1.58; I2 = 0.0%; P = 0.377) (Figure 3E) between the two groups.

Non-comparative studies reporting outcomes of laparoscopic surgery

A total of 8 non-comparative studies[21,22,35-40], which reported outcomes for the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of laparoscopic surgery in the setting of early GBC, were identified and included in the present review. All 8 studies were retrospective, including 7 single-center and 1 two-center studies. The above studies involved patients operated from 2001 to 2009, and one study[35] assessed patients undergoing revision surgery of IGBC. Due to the unknown specific number of patients in the surgical types, we excluded the study performed by Ome et al[21]. Of the included patients, 120 underwent LRC while 10 underwent LSC. The overall survival was considerable, especially the study conducted by Shirobe et al[36] which showed that the 5-year survival rate was 100% for T1b patients and 83.3% for T2 patients. The operation time ranged from 162 to 490 min, while blood loss during surgery varied from 50 to 196.4 mL. Only 3 studies[21,38,39] reported the number of lymph nodes resected during surgery, which ranged from 4 to 8. Six studies showed postoperative hospital stay, which was mostly between 4 to 6.4 d, except one study which was 12 d. Moreover, postoperative complication rates were shown in 4 studies[22,37-39], and ranged between 8.5% and 16.7%.

DISCUSSION

This is the latest meta-analysis to evaluate the influence of laparoscopic surgery on oncological survival, intraoperative, perioperative, and postoperative outcomes in patients with early GBC. The present study demonstrated that laparoscopic surgery has a comparable impact on 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival to that of open surgery after resection of early GBC. Patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were not more vulnerable to operative outcomes with a significantly reduced hospital stay than those who underwent open surgery.

GBC is considered a highly lethal disease due to the fact that many patients are asymptomatic in both early and more advanced stages. Unlike other gastrointestinal organs, the gallbladder lacks submucosa and the Rokitansky–Aschoff sinus, which makes it difficult to predict tumor invasion of GBC accurately[41]. With regard to the treatment of GBC, cholecystectomy, partial liver resection, lymphadenectomy, and even reconstruction of the digestive tract are required, making curative surgery technically challenging. These surgical techniques result in a very low survival rate for early GBC patients, even for patients with T1 GBC. There is still controversy regarding the optimal surgical method, including laparoscopic and open surgery, for early GBC (stage ≤ T2).

With the development of surgical instrumentation and technical innovation, laparoscopic surgery is widely used for most gastrointestinal cancers, including stomach and colon cancers. As similar survival outcomes to open surgery have been demonstrated, laparoscopic surgery tends to be a standardized treatment for patients with early-stage cancers[41,42]. Theoretically, there are many advantages of the laparoscopic approach over laparotomy. Laparoscopic surgery offers the chance of minimally invasive treatment for patients with some benign lesions, which cannot be differentiated from GBC preoperatively. However, performing a laparoscopic resection may accomplish comparable radicality to the open approach with considerable beneficial outcomes, including less intraoperative blood loss, less pain, early ambulation, lower postoperative complication rate, and similar overall survival. Nevertheless, according to the guidelines of the Japanese Association of Biliary Surgery[14], laparoscopic surgery is not recommended for patients with GBC. The tumor is likely to be exposed by conducting this procedure and there is an increased risk of gallbladder perforation and bile spillage, and both of these can result in possible tumor cell implantation. Furthermore, port-site recurrence after laparoscopic surgery for malignancies has been reported, such as GBC and gastric cancer. Although Schaeff et al[43] reported a port-site recurrence rate of 17% in unsuspected GBC in the 1990s, technical shortcomings existed such as not using retrieval bags and surgeon-related rough surgical skills[44]. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in port-site/wound recurrence between laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal carcinoma[45]. The final reason against the laparoscopic approach is the concern with regard to safety and feasibility. Not only similar outcomes were observed after surgery for gastric and pancreatic carcinoma, but Itano et al[30] also reported similar oncological outcomes in the laparoscopic group to those in the open group.

A previous meta-analysis performed by Zhao et al[46] concluded that patients with GBC have a non-inferior prognosis following laparoscopic simple cholecystectomy, and laparoscopic extended cholecystectomy can also be performed in selective patients in high-volume specialized expert centers. However, 6 of the included studies were published ten years ago and even in 2000, which may have produced publication bias resulting in relatively inaccurate conclusions. In addition, all included studies in the present study were published in the past ten years, making this the most up-to-date meta-analysis. Instead of using OR to analyze overall survival, we chose HR, which has a cumulative effect, to perform a meta-analysis of overall survival. Surprisingly, no significant differences in 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival between the 2 groups were observed with all HRs less than 1 (0.54, 0.75, and 0.71, respectively). Importantly, port-site/wound recurrence, which is caused by direct and indirect implantation of cancer cells at the port sites during laparoscopic surgery[47], was not analyzed due to incomplete data and less port-site/wound recurrence occurred due to the use of retrieval bags during surgery. Several studies have reported that it is essential for surgeons to perform lymph node dissection to improve the survival of GBC patients[22,35]. Notably, the present study showed that there was no difference in the number of lymph nodes resected between the laparoscopic and open surgery groups. Furthermore, we conducted a meta-analysis of operation time, blood loss, number of lymph nodes resected, and postoperative hospital stay, while Zhao et al[46] did not.

The purpose of this study was not only to compare the results of laparoscopic surgery to those of open surgery, but also to introduce emerging techniques of laparoscopic surgery for early GBC. An appropriate retrieval system is important for preventing port-site/wound contamination during laparoscopic surgery. It is easy for surgeons to handle the resected specimen with a low risk of contamination even if the specimen accidentally ruptures during retrieval. Therefore, retrieval bags are highly recommended in laparoscopic surgery for preoperatively suspected or diagnosed GBC to prevent tumor cell dissemination. Nowadays, surgeons prefer parenchyma-sparing treatments to extended treatments such as nonanatomical wedge resection[17,22,48]. After excluding hepatoduodenal ligament and locoregional involvement, nonanatomical gallbladder bed resection with a distal clearance of ≥ 2 cm is considered to obtain negative margins histologically[49,50]. Lymphadenectomy is a prognostic factor for overall survival in GBC, but there is no consensus on lymphadenectomy extension. For GBC stage Tis and T1a, simple cholecystectomy without lymphadenectomy is considered, while for stage T1b, hepatoduodenal ligament lymph node resection (hilar, cystic, pericholedochal, perihepatic, and periportal lymph nodes) is regarded as the optimal strategy. Extraregional lymph node dissection involving peripancreatic and periduodenal lymph nodes, and dissection of lymph nodes around the common hepatic, celiac, and inferior mesenteric artery are recommended for T2 patients[51-53].

We acknowledge several limitations in the present study. First, all comparative studies were retrospective, which increases the risk of potential publication and selection bias. Second, the treatment within each group was a little different. We performed a meta-analysis of primary and secondary outcomes of complex procedures in both groups. Due to the limited number of included studies, subgroup analysis of specific procedures in each group should be conducted in the future. Moreover, as a significant factor of prognosis, the recurrence rate was not assessed in our study, and a meta-analysis of recurrence rate will be performed when more high-quality studies are included.

In conclusion, comparable 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival after laparoscopic surgery to that after open surgery demonstrated that laparoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible treatment for early GBC. Moreover, the laparoscopic approach is non-inferior to open surgery in terms of operation-related outcomes with a reduced length of hospital stay.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

There is still controversy as to whether laparoscopic surgery leads to a poor prognosis compared to the open approach for early gallbladder carcinoma (GBC).

Research motivation

The safety and feasibility of laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for early GBC are controversial.

Research objectives

To compare the currently available results of laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery to confirm which is better for early GBC.

Research methods

We systematically reviewed the literature on laparoscopic surgery and open surgery, and included relevant studies for meta-analysis.

Research results

The results indicated no significant differences in the 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, the number of lymph nodes resected, and postoperative complications between the laparoscopic and open surgery groups. However, patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery had a reduced length of hospital stay than those who underwent open surgery.

Research conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible alternative to open surgery with comparable 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival and operation-related outcomes in early GBC.

Research perspectives

More prospective studies should be performed due to the limited sample size and lack of recurrence data in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Yun Cai for polishing our manuscript. We are grateful to our colleagues for their assistance in checking data in the included studies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors deny any conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Peer-review started: December 29, 2019

First decision: January 19, 2020

Article in press: February 28, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cakmak A, Garg R S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Xu Feng, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Jia-Sheng Cao, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Ming-Yu Chen, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Bin Zhang, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Sarun Juengpanich, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Jia-Hao Hu, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Win Topatana, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Shi-Jie Li, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Ji-Liang Shen, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Guang-Yuan Xiao, Department of General Surgery, Jiaxing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jiaxing 314000, Zhejiang Province, China.

Xiu-Jun Cai, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China.

Hong Yu, Department of General Surgery, Sir Run-Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China. 3195016@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99–109. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henley SJ, Weir HK, Jim MA, Watson M, Richardson LC. Gallbladder Cancer Incidence and Mortality, United States 1999-2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1319–1326. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gourgiotis S, Kocher HM, Solaini L, Yarollahi A, Tsiambas E, Salemis NS. Gallbladder cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavallaro A, Piccolo G, Di Vita M, Zanghì A, Cardì F, Di Mattia P, Barbera G, Borzì L, Panebianco V, Di Carlo I, Cavallaro M, Cappellani A. Managing the incidentally detected gallbladder cancer: algorithms and controversies. Int J Surg. 2014;12 Suppl 2:S108–S119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.08.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy A, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, Huitzil D, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, D'Angelica M, Dematteo RP, Blumgart LH, O'Reilly EM. Gallbladder cancer (GBC): 10-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre (MSKCC) J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:485–489. doi: 10.1002/jso.21141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong Y, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. Gallbladder cancer: comparison of patients presenting initially for definitive operation with those presenting after prior noncurative intervention. Ann Surg. 2000;232:557–569. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip VS, Gomez D, Brown S, Byrne C, White D, Fenwick SW, Poston GJ, Malik HZ. Management of incidental and suspicious gallbladder cancer: focus on early referral to a tertiary centre. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:641–647. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aloia TA, Járufe N, Javle M, Maithel SK, Roa JC, Adsay V, Coimbra FJ, Jarnagin WR. Gallbladder cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:681–690. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayo SC, Shore AD, Nathan H, Edil B, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, Herman J, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. National trends in the management and survival of surgically managed gallbladder adenocarcinoma over 15 years: a population-based analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1578–1591. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gumbs AA, Jarufe N, Gayet B. Minimally invasive approaches to extrapancreatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:406–414. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal AK, Javed A, Kalayarasan R, Sakhuja P. Minimally invasive versus the conventional open surgical approach of a radical cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer: a retrospective comparative study. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:536–541. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo S, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Miyakawa S, Tsukada K, Nagino M, Furuse J, Saito H, Tsuyuguchi T, Yamamoto M, Kayahara M, Kimura F, Yoshitomi H, Nozawa S, Yoshida M, Wada K, Hirano S, Amano H, Miura F Japanese Association of Biliary Surgery; Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery; Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Guidelines for the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas: surgical treatment. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:41–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki M, Yoshitomi H, Miyakawa S, Uesaka K, Unno M, Endo I, Ota T, Ohtsuka M, Kinoshita H, Shimada K, Shimizu H, Tabata M, Chijiiwa K, Nagino M, Hirano S, Wakai T, Wada K, Isayama H, Okusaka T, Tsuyuguchi T, Fujita N, Furuse J, Yamao K, Murakami K, Yamazaki H, Kijima H, Nakanuma Y, Yoshida M, Takayashiki T, Takada T. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of biliary tract cancers 2015: the 2nd English edition. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:249–273. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal AK, Kalayarasan R, Javed A, Gupta N, Nag HH. The role of staging laparoscopy in primary gall bladder cancer--an analysis of 409 patients: a prospective study to evaluate the role of staging laparoscopy in the management of gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg. 2013;258:318–323. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318271497e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gumbs AA, Hoffman JP. Laparoscopic completion radical cholecystectomy for T2 gallbladder cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3221–3223. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinert R, Nestler G, Sagynaliev E, Müller J, Lippert H, Reymond MA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and gallbladder cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:682–689. doi: 10.1002/jso.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon YS, Han HS, Cho JY, Choi Y, Lee W, Jang JY, Choi H. Is Laparoscopy Contraindicated for Gallbladder Cancer? A 10-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gumbs AA, Milone L, Geha R, Delacroix J, Chabot JA. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:519–520. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ome Y, Hashida K, Yokota M, Nagahisa Y, Okabe M, Kawamoto K. Laparoscopic approach to suspected T1 and T2 gallbladder carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2556–2565. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i14.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Ahn KS, Kim YH, Lee KH. Laparoscopic approach for suspected early-stage gallbladder carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145:128–133. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815–2834. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson PR, Smith CT, Hutton JL, Marson AG. Aggregate data meta-analysis with time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med. 2002;21:3337–3351. doi: 10.1002/sim.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goetze TO, Paolucci V. Prognosis of incidental gallbladder carcinoma is not influenced by the primary access technique: analysis of 837 incidental gallbladder carcinomas in the German Registry. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2821–2828. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2819-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Itano O, Oshima G, Minagawa T, Shinoda M, Kitago M, Abe Y, Hibi T, Yagi H, Ikoma N, Aiko S, Kawaida M, Masugi Y, Kameyama K, Sakamoto M, Kitagawa Y. Novel strategy for laparoscopic treatment of pT2 gallbladder carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3600–3607. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4116-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang JY, Heo JS, Han Y, Chang J, Kim JR, Kim H, Kwon W, Kim SW, Choi SH, Choi DW, Lee K, Jang KT, Han SS, Park SJ. Impact of Type of Surgery on Survival Outcome in Patients With Early Gallbladder Cancer in the Era of Minimally Invasive Surgery: Oncologic Safety of Laparoscopic Surgery. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3675. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng JW, Yang XH, Liu CW, Wu BQ, Sun DL, Chen XM, Jiang Y, Qu Z. Comparison of Laparoscopic and Open Approach in Treating Gallbladder Cancer. J Surg Res. 2019;234:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Cho JY, Choi Y. Retrospective comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic and open surgery for T2 gallbladder cancer - Thirteen-year experience. Surg Oncol. 2019;29:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ha TY, Yoon YI, Hwang S, Park YJ, Kang SH, Jung BH, Kim WJ, Sin MH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Song GW, Jung DH, Lee YJ, Park KM, Kim KH, Lee SG. Effect of reoperation on long-term outcome of pT1b/T2 gallbladder carcinoma after initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belli G, Cioffi L, D'Agostino A, Limongelli P, Belli A, Russo G, Fantini C. Revision surgery for incidentally detected early gallbladder cancer in laparoscopic era. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:531–534. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirobe T, Maruyama S. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy with lymph node dissection for gallbladder carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2244–2250. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3932-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palanisamy S, Patel N, Sabnis S, Palanisamy N, Vijay A, Palanivelu P, Parthasarthi R, Chinnusamy P. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy for suspected early gall bladder carcinoma: thinking beyond convention. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2442–2448. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro CM, Santibañez SP, Rivas TC, Cassis NJ. Totally Laparoscopic Radical Resection of Gallbladder Cancer: Technical Aspects and Long-Term Results. World J Surg. 2018;42:2592–2598. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Hou C, Xu Z, Wang L, Ling X, Xiu D. Laparoscopic treatment for suspected gallbladder cancer confined to the wall: a 10-year study from a single institution. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30:84–92. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.01.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piccolo G, Ratti F, Cipriani F, Catena M, Paganelli M, Aldrighetti L. Totally Laparoscopic Radical Cholecystectomy for Gallbladder Cancer: A Single Center Experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019;29:741–746. doi: 10.1089/lap.2019.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jang JY, Kim SW, Lee SE, Hwang DW, Kim EJ, Lee JY, Kim SJ, Ryu JK, Kim YT. Differential diagnostic and staging accuracies of high resolution ultrasonography, endoscopic ultrasonography, and multidetector computed tomography for gallbladder polypoid lesions and gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;250:943–949. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b5d5fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, Choi HS, Kim DW, Chang HJ, Kim DY, Jung KH, Kim TY, Kang GH, Chie EK, Kim SY, Sohn DK, Kim DH, Kim JS, Lee HS, Kim JH, Oh JH. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:767–774. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaeff B, Paolucci V, Thomopoulos J. Port site recurrences after laparoscopic surgery. A review. Dig Surg. 1998;15:124–134. doi: 10.1159/000018605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Itano O, Watanabe T, Jinno H, Suzuki F, Baba H, Otaka H. Port site metastasis of sigmoid colon cancer after a laparoscopic sigmoidectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:379–382. doi: 10.1007/s005950300086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guerrieri M, Campagnacci R, De Sanctis A, Lezoche G, Massucco P, Summa M, Gesuita R, Capussotti L, Spinoglio G, Lezoche E. Laparoscopic versus open colectomy for TNM stage III colon cancer: results of a prospective multicenter study in Italy. Surg Today. 2012;42:1071–1077. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao X, Li XY, Ji W. Laparoscopic versus open treatment of gallbladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;14:185–191. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_223_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neuhaus SJ, Texler M, Hewett PJ, Watson DI. Port-site metastases following laparoscopic surgery. Br J Surg. 1998;85:735–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gumbs AA, Hoffman JP. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy and Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy for gallbladder cancer. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1766–1768. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Vigano L, Kooby DA, Bauer TW, Frilling A, Adams RB, Staley CA, Trindade EN, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Capussotti L. Incidence of finding residual disease for incidental gallbladder carcinoma: implications for re-resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1478–1486; discussion 1486-1487. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez-Escobedo G, Marshall JM, Gunn JS. Chronic and acute infection of the gall bladder by Salmonella Typhi: understanding the carrier state. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hueman MT, Vollmer CM, Jr, Pawlik TM. Evolving treatment strategies for gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2101–2115. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0538-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen EH, Abraham A, Habermann EB, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SM, Virnig BA, Tuttle TM. A critical analysis of the surgical management of early-stage gallbladder cancer in the United States. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:722–727. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0772-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim SH, Chong JU, Lim JH, Choi GH, Kang CM, Choi JS, Lee WJ, Kim KS. Optimal assessment of lymph node status in gallbladder cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]