Highlights

-

•

Seropositivity is distributed evenly throughout Hungary.

-

•

Prevalence of antibodies against transmissible gastroenteritis is generally low.

-

•

Positive samples do not necessarily mean an efficient level of protection.

Keywords: Transmissible gastroenteritis, Indirect immunofluorescence, ELISA, Hungary

Abstract

Transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) is a highly contagious enteric disease of swine, which became infrequent with the appearance of porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV). TGE was last reported in Hungary in 2013 and the virus has not been found since, therefore a serological survey was planned to estimate the level of protection against it. 908 sera of sows from 93 farms were selected together with 174 archive samples from one farm covering a wider age group. All samples were screened with an indirect immunofluorescence (IF) test with a positive result of 15.42% and 17.82%, respectively. All IF-positive samples were examined with a commercial ELISA, revealing seropositivity against PRCV in almost all cases. These findings should serve as a recommendation to not omit TGE from the diagnostics of diarrhoea in swine.

Transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE) was first described in the United States in 1946 (Doyle & Hutchings 1946), then spread worldwide causing diarrhoea and vomiting in swine of all ages (Saif, Pensaert, Sestak, Yeo, & Jung, 2012). However, a few decades later (Laude, Van Reeth, & Pensaert, 1993) a clinically milder, endemic form of TGE emerged parallel with the appearance of porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV). PRCV is a mutant of TGE virus (TGEV), showing deletions mainly in the spike (S) gene. This difference is recognized minimal at the genetic level, which explains how both viruses are considered as one species Alphacoronavirus 1 (Lin et al., 2015), but it can be great phenotypically, as it may be the result of their different tissue tropism, as the expressed S glycoprotein is responsible for cell entry (Ballesteros, Sanchez, & Enjuanes, 1997). In contrast to TGEV, PRCV has respiratory tropism and usually causes an undiscerned subclinical infection (Pensaert, Cox, Van Deun, & Callebaut, 1993), which can induce the production of cross-reacting antibodies, causing difficulties in serological diagnostics (Miyazaki, Fukuda, Kuga, Takagi, & Tsunemitsu, 2010). The virus neutralization assay cannot be used to differentiate TGEV and PRCV, therefore various enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were developed using monoclonal antibodies targeting the different epitopes of the S protein (Carman et al., 2002). Serological tests such as these can be used to monitor herd status or newly transported animals, as TGEV/PRCV-seronegative farms are at risk of the disease, although TGE outbreaks occurred only sporadically since the appearance of PRCV (Lőrincz, Biksi, Andersson, Cságola, & Tuboly, 2013).

The aim of our study was to determine the proportion of TGEV-seropositivity in Hungary, assuming a high rate, since the virus was not found in the last few years (data not shown).

Serum samples of sows were sent to the National Food Chain Safety Office, Veterinary Diagnostic Directorate to monitor swine herds as part of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) eradication plan in Hungary. From these samples 908 sera were selected from 93 farms, reaching 10 samples per farm, if possible. The selected samples were collected throughout the country in 2015-2016. To examine different age groups, samples collected from farm “F” in the northeast part of Hungary in 2013 were also included in this study. The 174 samples, reaching approximately 15 samples per group from farm “F” could be divided by age as follows: 2, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 60, 90, 120, 150 day-old pigs and sows.

The cell-culture adapted Purdue-115 strain of TGEV (Tuboly & Nagy, 2001) was propagated on swine testis (ST) cells, then the virus titer determined based on the Spearman-Karber method. Using the result of 1333.52 µL TCID50 (50% Tissue Culture Infective Dose) 1 MOI (Multiplicity of Infection) was calculated as 7.5 µL virus on 10,000 cells per well for the indirect immunofluorescence (IF). After 24 h of proliferation cells were inoculated, then another 24 h later fixed with a 1:1 ratio mixture of concentrated acetone and ethanol, lastly air dried and stored at −20 °C, if not used immediately. Serum samples in a 1:4 dilution were incubated in the prepared 96-well plates at 37 °C for one hour, followed by an incubation with anti-pig immunoglobulin G (Sigma-Aldrich) for another hour. Cell staining was examined under a fluorescence microscope. Positive serum samples from farm “F” were diluted serially and examined repeatedly to determine the relative amount of specific antibodies. All positive samples were examined with a commercial ELISA kit (INgezim Corona Diferencial 2.0, Ingenasa) according to the manufacturer's instructions to differentiate antibodies produced against TGEV or PRCV.

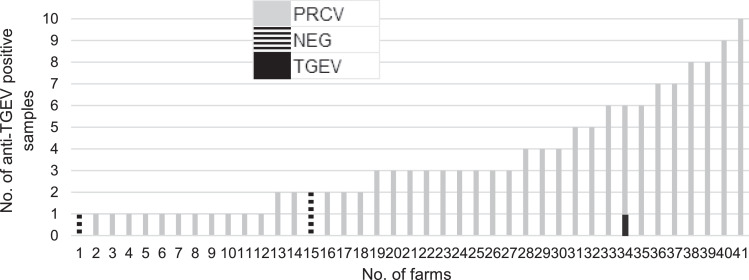

Out of 93 farms anti-TGEV antibodies were detected in 41 farms distributed evenly throughout the country without clustering in a particular area. Out of 908 samples the number of positives reached 140 with only a few reactions from many farms, as illustrated in Fig. 1. We detected a total of 31 positives from 174 samples collected in farm “F”, distributed by age and number of positives as follows: 2 days = 11, 7 days = 2, 14 days = 5, 21 days = 2, 35 days = 2, 60 days = 1 and 90 days = 8. The titer of the samples were considerably low in a range of 1:4 to 1:128. The differentiating ELISA showed that almost all anti-TGEV antibodies found in the IF test were produced against PRCV. Only one sample contained antibodies produced against TGEV and three IF positive samples remained negative for both viruses with ELISA, indicated in different shades of grey in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The number of samples per each farm showing anti-TGEV antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence (IF) or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). TGEV: transmissible gastroenteritis virus, PRCV: porcine respiratory coronavirus, NEG: IF-positive and ELISA-negative.

In this study our aim was to execute a nationwide survey to determine the relative prevalence of antibodies against TGEV in Hungary estimating a high rate, as the occurrence of the disease was not reported in recent years. Our hypothesis was denied, since the overall seropositivity based on the IF test of 908 samples was only 15.42%. Examining different age groups in farm “F” showed similar results with a seropositivity of 17.82%. It was interesting to find no positive sows, although it should be noted that there was no connection between the samples of piglets and sows. A differentiating ELISA revealed that actually almost all positive sera had antibodies against PRCV. These antibodies can react to TGEV, as confirmed also in this study by the IF test, but frequent reinfections with PRCV are needed to reach an efficient titer for protection against TGE (Laude et al., 1993), which was not realized in the examined samples of farm “F”. The IF positive, but ELISA negative samples could be also explained by the relative amount of antibodies, which was not sufficient to cross the threshold of the kit. The only TGEV positive serum was found in a farm with five PRCV positive and four negative samples, which may indicate that there was an unapparent TGE outbreak overcome by protective anti-PRCV antibodies.

In conclusion, we found a low level of protection against TGEV throughout Hungary, which can serve notice that a TGE outbreak is not inconceivable. Based on the lack of reports of such events worldwide, the possibility remains unaccentuated, still our results should attract the attention of field clinicians and laboratory staff to not leave TGEV out from the diagnostics of diarrhoea in swine.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organisations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the University of Veterinary Medicine, Budapest (grant number NKB 2017, 69P00RH02) and the Hungarian Ministry of Human Capacities (grant number FEKUTSTRAT 2018, 17896-4).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.vas.2018.11.003.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Ballesteros M.L., Sanchez C.M., Enjuanes L. Two amino acid changes at the N-terminus of transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus spike protein result in the loss of enteric tropism. Virology. 1997;227:378–388. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman S., Josephson G., McEwen B., Maxie G., Antochi M., Eernisse K. Field validation of a commercial blocking ELISA to differentiate antibody to transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and porcine respiratory coronavirus and to identify TGEV-infected swine herds. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2002;14:97–105. doi: 10.1177/104063870201400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L.P., Hutchings L.M. A transmissible gastroenteritis in pigs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1946;108:257–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laude H., Van Reeth K., Pensaert M. Porcine respiratory coronavirus: Molecular features and virus-host interactions. Veterinary Research. 1993;24:125–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.M., Gao X., Oka T., Vlasova A.N., Esseili M.A., Wang Q. Antigenic relationships among porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and transmissible gastroenteritis virus strains. Journal of Virology. 2015;89:3332–3342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03196-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lőrincz M., Biksi I., Andersson S., Cságola A., Tuboly T. Sporadic re-emergence of enzootic porcine transmissible gastroenteritis in Hungary. Acta Veterinaria Hungarica. 2013;62:125–133. doi: 10.1556/AVet.2013.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki A., Fukuda M., Kuga K., Takagi M., Tsunemitsu H. Prevalence of antibodies against transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine respiratory coronavirus among pigs in six regions in Japan. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 2010;72:943–946. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pensaert M., Cox E., Van Deun K., Callebaut P. A sero-epizootiological study of porcine respiratory coronavirus in belgian swine. Veterinary Quarterly. 1993;15:16–20. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1993.9694361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saif L.J., Pensaert M.P., Sestak K., Yeo S., Jung K. Coronaviruses. In: Zimmerman J.J., Karriker L.A., Ramirez A., Schwartz K.J., Stevenson G.W., editors. Diseases of swine. Wiley-Blackwell; New Jersey: 2012. pp. 1821–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Tuboly T., Nagy É. Construction and characterization of recombinant porcine adenovirus serotype 5 expressing the transmissible gastroenteritis virus spike gene. Journal of General Virology. 2001;82:183–190. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-1-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.