Significance

Antibodies against neuronal receptors and synaptic proteins are associated with a group of ill-defined central nervous system (CNS) autoimmune diseases named autoimmune encephalitides (AE), characterized by an abrupt onset of seizures and movement and psychiatric deficits. How these antibodies enter the brain to trigger neuroinflammation, and how they affect the function of neural circuits, remains poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that Th17 lymphocytes are critical for entry of autoantibodies into the CNS, persistent microglia activation, and neurophysiological deficits in odor processing, in a mouse model of postinfectious autoimmune encephalitis triggered by multiple infections with group A Streptococcus. Our findings emphasize the critical role that Th17 lymphocytes play in disease pathogenesis to impair CNS function in AE syndromes.

Keywords: autoimmune encephalitis, blood–brain barrier, Th17 lymphocyte, postinfectious basal ganglia encephalitis, olfactory circuitry

Abstract

Antibodies against neuronal receptors and synaptic proteins are associated with a group of ill-defined central nervous system (CNS) autoimmune diseases termed autoimmune encephalitides (AE), which are characterized by abrupt onset of seizures and/or movement and psychiatric symptoms. Basal ganglia encephalitis (BGE), representing a subset of AE syndromes, is triggered in children by repeated group A Streptococcus (GAS) infections that lead to neuropsychiatric symptoms. We have previously shown that multiple GAS infections of mice induce migration of Th17 lymphocytes from the nose into the brain, causing blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, extravasation of autoantibodies into the CNS, and loss of excitatory synapses within the olfactory bulb (OB). Whether these pathologies induce functional olfactory deficits, and the mechanistic role of Th17 lymphocytes, is unknown. Here, we demonstrate that, whereas loss of excitatory synapses in the OB is transient after multiple GAS infections, functional deficits in odor processing persist. Moreover, mice lacking Th17 lymphocytes have reduced BBB leakage, microglial activation, and antibody infiltration into the CNS, and have their olfactory function partially restored. Th17 lymphocytes are therefore critical for selective CNS entry of autoantibodies, microglial activation, and neural circuit impairment during postinfectious BGE.

Antibody-mediated central nervous system (CNS) autoimmune disease is initiated when circulating antibodies inappropriately recognize neuronal receptors or synaptic proteins as foreign epitopes. This is exemplified by various autoimmune encephalitic (AE) syndromes including anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis, limbic encephalitis, and postinfectious basal ganglia encephalitis (BGE), which trigger abrupt onset of movement and psychiatric symptoms in healthy individuals (1, 2). The mechanisms by which these pathological autoantibodies enter the brain to trigger neuropathology and how they functionally affect neural circuits remain obscure (3, 4), since the blood–brain barrier (BBB) normally prevents circulating antibodies from entering into the CNS (4, 5).

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) (Streptococcus pyogenes) infections during childhood are associated with autoimmune complications of the heart (acute rheumatic fever), kidney (glomerulonephritis), and brain (6). The CNS autoimmune response targets the basal ganglia and presents with either movement (Sydenham’s chorea [SC]) or psychiatric (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections [PANDAS]) symptoms (7). Recent statistics indicate that 1 in 200 children (0.5%) in the United States is affected with PANDAS (8) and >25% of pediatric cases with obsessive-compulsive disorders and tic disorders (e.g., Tourette’s syndrome) originate as PANDAS (9). The humoral adaptive immune response plays an important role in disease pathogenesis in humans and rodent models for SC/PANDAS (7, 10, 11). Discovery of antineuronal autoantibodies targeting cell surface receptors in the basal ganglia (10, 12–14), positive responses to immunotherapy in patients (15, 16), and the ability of antibodies to elicit behavioral abnormalities into naive rodents after adoptive transfer (reviewed in refs. 4 and 6) are consistent with an autoimmune mechanism. How the BBB is breached to allow pathogenic antibodies to enter the CNS, remains a fundamental unanswered question.

A compelling immune-mediated mechanism for BBB disruption is through the action of T cells, in particular Th17 lymphocytes, which are essential to initiate and propagate neurovascular dysfunction and disease pathogenesis in both multiple sclerosis (MS) and its animal model experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (17, 18). However, the contribution of Th17 lymphocytes to AE pathogenesis is largely unexplored. Classical biopsy studies in postmortem human brain have shown perivascular CD3+ T cells in SC patients (19), as well as recent studies in anti-Hu and anti-LGI1/Caspr2 AE disease patients (20). Mature T cells are required for disease induction in a rodent model of anti-NMDAR autoimmune encephalitis, in which immune-competent mice are actively immunized with conformationally stabilized, native-like NMDARs (21). We have previously established a mouse model for postinfectious BGE that features multiple intranasal (i.n.) infections with live GAS (22). This mimics the human immune response to infection, by inducing GAS-specific CD4+ Th17 cell differentiation in the mouse nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT), an analog of human adenoids/tonsils. These GAS-specific Th17 cells migrate from the nose into the brain and are associated with increased BBB permeability, microglial activation, and loss of excitatory synaptic proteins in the olfactory bulb (OB) (22). How Th17 lymphocytes contribute to vascular dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and olfactory circuit physiological deficits has not been addressed. Here, we demonstrate that while the loss of excitatory synapses in the OB is transient after multiple GAS infections, odor-processing deficits are persistent. Moreover, mice lacking Th17 lymphocytes have reduced BBB deficits, microglial activation, antibody infiltration into the CNS, and show a partial restoration of olfactory function. Th17 lymphocytes are therefore critical for CNS entry of autoantibodies, microglial activation, and neural circuit impairment in postinfectious BGE.

Results

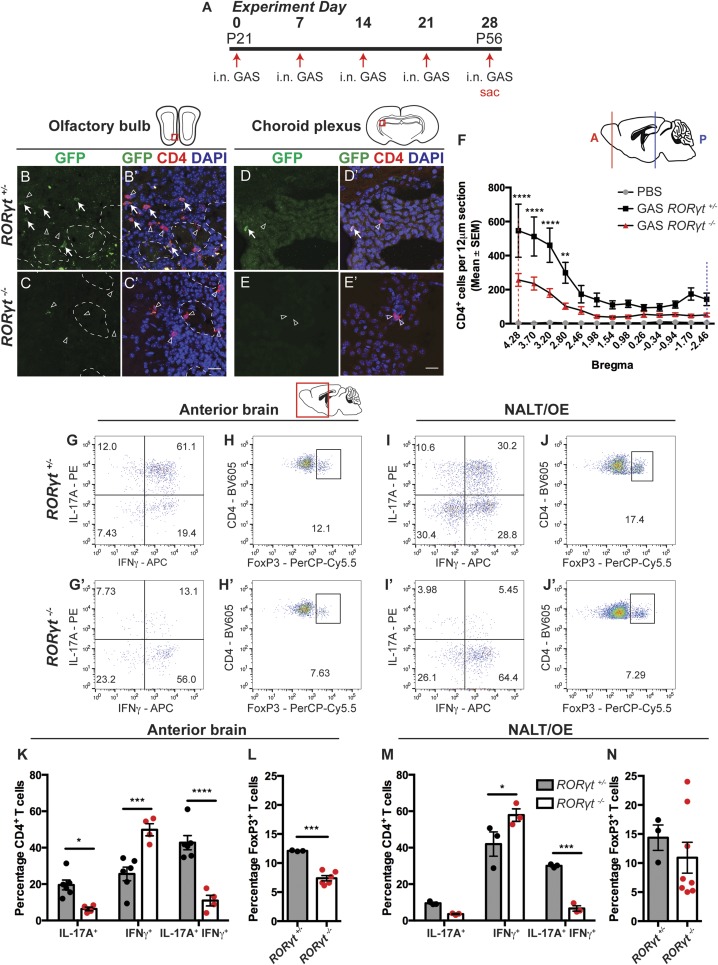

CD4+ Th17, IFN-γ+ Th17, and Regulatory T Cell Numbers Are Reduced in the CNS of RORγt−/− Mice after Multiple GAS Infections.

To track and assess the roles of Th17 cells in the postinfectious BGE pathology, we performed multiple i.n. GAS infections in RORγteGFP/+ and RORγteGFP/eGFP (designated as RORγt+/− and RORγt−/−) mice, in which the coding region for RORγt, a transcription factor required for Th17 specification, is replaced with eGFP (Fig. 1A) (23). RORγt−/− mice are immunocompromised and show a ∼50% survival rate to infection compared to RORγt+/− mice (∼10%) due to sepsis (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D) (22, 24). After multiple i.n. GAS infections, most CD4+ T cells in RORγt+/− mice reside in the anterior part of the brain (bregma 4.28 to 2.46), and a subset (∼36%; Th17 subtype) contain eGFP (Fig. 1 B, B′, D, and D′ and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 M–O). eGFP+ Th17 cells are also concentrated in the anterior CNS (OB and anterior olfactory nucleus [AON]) as well as the choroid plexus (bregma −1.70, −2.46; Fig. 1 B, B′, D, D′, and F). Surviving RORγt−/− GAS-infected mice show a ∼58% decrease in total CD4+ T cells in the CNS by immunofluorescence, with no detectable CD4+ eGFP+ cells (bregma 4.28 to 2.80; Fig. 1 C, C′, E, E′, and F).

Fig. 1.

Th17 lymphocytes and IFNγ+ Th17 lymphocytes are reduced in brains and NALT/OE of RORγt −/− mice after multiple GAS infections. (A) Experimental timeline for intranasal (i.n.) infections with live GAS. (B–E′) Immunofluorescence for GFP (green), CD4 (red), and DAPI (blue) in the olfactory bulb (OB) and choroid plexus of i.n. GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice. GFP+ Th17 lymphocytes are marked with white arrows and GFP− lymphocytes with arrowheads. (F) Quantification of CD4+ T cell distribution in the brains of PBS (gray), GAS-infected RORγt+/− (black), and RORγt−/− (red) mice. The x axis shows distance from the bregma, and the y axis shows CD4+ T cell numbers per 12-μm section. The dashed red and blue vertical lines represent relative positions in the brain (solid lines). The total number of CD4+ T cells in the brain is reduced by more than 50% in RORγt−/− compared to RORγt+/− mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5 PBS, n = 9 GAS RORγt+/−, and n = 9 GAS RORγt−/− mice; bregmas +4.28, +3.7, +3.2, ****P < 0.0001; bregma 2.8, **P = 0.0062 by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc correction). (G–J′) Representative flow cytometry of CD4+ lymphocytes purified from anterior brain regions or NALT/OE of RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice and stained for either intracellular cytokines (G, G′, I, and I′) or CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells (H, H′, J, and J′). (K and M) Quantitative cytokine profile analysis of lymphocytes purified from brains (K) or NALT/OE (M) of GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice. Th17 lymphocytes and IFNγ+ Th17 lymphocytes are significantly reduced in brains and NALT/OE of RORγt −/− mice after multiple GAS infections. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (K) n = 6 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 4 GAS RORγt−/− mice; IL-17A+, *P = 0.353; IFNγ+, ***P = 0.0001; IL-17A+ IFNγ+, ****P < 0.0001. (M) n = 3 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 3 GAS RORγt−/− mice; IL-17A+, P = 0.5056 (NS); IFN-γ+, *P = 0.0115; IL-17A+ IFN-γ+, ***P = 0.0006; two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s test for multiple comparisons. (L and N) Treg lymphocyte analysis from brains or NALT/OE of RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice after GAS infections shows reduction in the brain, but not NALT of RORγt −/− mice after multiple GAS infections [mean ± SEM; (L) n = 3 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 6 GAS RORγt−/− mice, ***P = 0.0001; (N) n = 3 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 8 GAS RORγt−/− mice; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test with Welch’s correction for unequal variance]. (Scale bars, 20 μm.)

We then performed T cell subtype analysis from the anterior brain, NALT, and olfactory epithelium (OE) using flow cytometry. IFN-γ+ Th17 lymphocytes are most abundant in the CNS (IL-17A+ IFN-γ+; 42.75%), followed by Th1 (IFN-γ+; 25.57%), Th17 (IL-17A+; 19.52%), and regulatory T (Treg) (FoxP3+; 12.1%) cells in GAS-infected RORγt+/− mice (Fig. 1 G–J and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The proportions of CD4+ T cell subtypes are similar between the anterior brain and NALT/OE but are different in spleen (Fig. 1 G–M and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 E–H). In the brains of GAS-infected RORγt−/− mice, there is a significant reduction in IFN-γ+ Th17 (IL-17A+ IFN-γ+), Th17 (IL-17A+), and Treg lymphocytes (Fig. 1 G′, H′, K, and L). This is accompanied by a significantly increased fraction of Th1 (IFN-γ+) cells, which are the most abundant (48%) T cells in the CNS (Fig. 1 G′, H′, and K). Lymphocyte populations in NALT/OE, but not the spleen, show similar trends after GAS infections in RORγt−/− mice (Fig. 1 I′, J′, M, and N and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 E–H), reinforcing our hypothesis that CD4+ T cells in the brain originate from the NALT/OE. Despite their immunocompromised state, viable RORγt−/− mice generate a robust CD4+ cellular immune response in the NALT/OE, restricting bacteria to the nasal mucosa (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 K and L′).

To determine whether T cell infiltration into the brain requires i.n. infections, we performed subcutaneous (s.c.) immunization with heat-killed GAS (HK-GAS) emulsified with complete Freund’s adjuvant, followed by intravenous (i.v.) injection of the BBB-disrupting agent Bordetella pertussis toxin (25, 26). This route of immunization produces autoantibodies that target the CNS, causing behavioral abnormalities in mice (25, 26). In contrast to i.n. GAS infections, s.c. immunizations do not generate a robust CD4+ T cell population in the CNS (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A–C). Thus, the route of bacterial exposure regulates the presence of T cells in the brain.

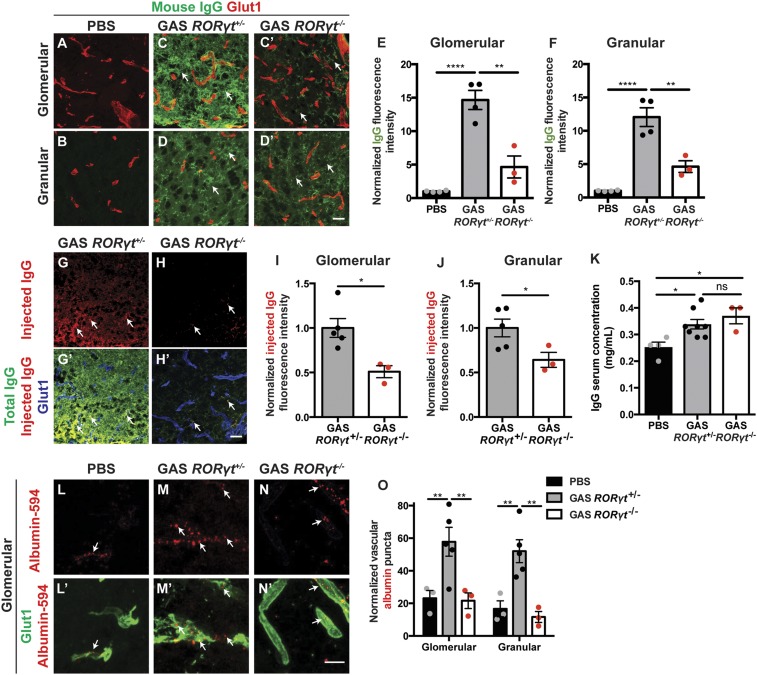

CNS Th17 Lymphocytes Regulate BBB Permeability to Antibodies during Postinfectious BGE.

We assessed the contribution of Th17 lymphocytes to BBB dysfunction, because both IL-17A and IFN-γ disrupt endothelial tight junctions (TJs) in vitro and in vivo (27). The BBB becomes leaky to serum proteins not only when TJ complexes are disrupted but also when vesicular transcytosis is up-regulated in CNS endothelial cells (18). To investigate the function of TJs, we injected biocytin-tetramethylrhodamine (biocytin-TMR) (870 Da) tracer i.v. into RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice 48 h after the final i.n. GAS infection (22, 28–30). The area and intensity of tracer deposition did not differ between two genotypes after GAS infections in OB, although it was significantly higher than PBS mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B–H). Structural abnormalities in CNS endothelial TJs [gaps and lack of junctional proteins that are found in many neurological diseases associated with BBB dysfunction (28, 29)] (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 I–M) and levels for several TJ proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 N and O) are also comparable between the two genotypes after GAS infections. Thus, multiple GAS infections induce some structural defects in BBB TJs even when Th17 lymphocytes are essentially absent from the CNS.

Next, we measured the area and intensity of serum IgG deposition in brain tissue from RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice after multiple GAS infections. In contrast to biocytin-TMR, leakage of serum IgG was significantly reduced in RORγt−/− compared to RORγt+/− OBs (Fig. 2 A–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and A′). PBS-treated control mice had no serum IgG in the OB (Fig. 2 A, B, E, and F). Importantly, total serum IgG levels as well as GAS-specific IgGs were similar between GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice (Fig. 2K and SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). Therefore, the absence of serum IgG in the brains of RORγt−/− mice is not due to either a reduction in total serum IgG levels or an aberrant humoral immune response to GAS.

Fig. 2.

Th17 lymphocytes regulate BBB permeability to serum IgG after multiple GAS infections by up-regulating endothelial cell transcytosis. (A–D′) Immunofluorescence for serum IgG (green) and Glut-1+ blood vessels (red) in the glomerular and granular layers of the OB in PBS- and GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice. PBS-inoculated mice show no BBB permeability to serum IgG (A and B). GAS RORγt+/− brains show strong deposition of serum IgG in OB (C and D, arrows), whereas GAS RORγt−/− mice show significantly less IgG deposition in the OB (C′ and D′). Quantification of IgG leakage in (E) glomerular and (F) granular layers of the OB shows that RORγt−/− mice have significantly less IgG deposition in the OB. Data are shown as mean ± SEM [n = 4 PBS, n = 4 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 3 GAS RORγt−/− mice; (E) ****P < 0.0001, PBS vs. GAS RORγt+/−; P = 0.1466 [non significant (NS)], PBS vs. GAS RORγt−/−; **P = 0.0010, GAS RORγt+/− vs. GAS RORγt−/− by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc correction; (F) ****P < 0.0001, PBS vs. GAS RORγt+/−; P = 0.0829 (NS) PBS vs. GAS RORγt−/−; **P = 0.0022 GAS RORγt+/− vs. RORγt−/− by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc correction]. Intravenous injection of exogenous Alexa 488-labeled mouse IgG (pseudocolored in red) into GAS-infected mice is detected in the OB of (G and G′) RORγt+/− but not (H and H′) RORγt−/− mice. (I and J) Quantification of exogenous IgG in the glomerular and granular OB regions shows twofold higher levels in RORγt+/− compared to RORγt−/− mice. Data are shown as mean ± SEM [n = 5 GAS RORγt+/−; n = 3 GAS RORγt−/− mice; (I) *P = 0.0168 and (J) *P = 0.0488 by Student’s t test]. (K) Quantification of total serum IgG concentration by ELISA shows elevated levels in GAS-infected mice, but no difference between two genotypes. (L–N′) Endothelial uptake of albumin-Alexa 594 (arrows) is detected at high levels in GAS RORγt+/− brains. GAS RORγt−/− mice show reduced endothelial albumin-Alexa 594 uptake similar to healthy controls. (O) Quantification of albumin puncta within the vasculature of the glomerular and granular OB [n = 3 PBS, n = 5 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 3 GAS RORγt−/− mice. (O) Glomerular: **P = 0.0099 PBS vs. GAS RORγt+/−; P = 0.9988 (NS) PBS vs. GAS RORγt−/−; **P = 0.0072 GAS RORγt+/− vs. RORγt−/−; granular: **P = 0.0086 PBS vs. GAS RORγt+/−; P = 0.9615 (NS) PBS vs. GAS RORγt−/−; **P = 0.003 GAS RORγt+/− vs. RORγt−/− by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc correction]. (Scale bars: in D′ and H′, 20 μm; in N′, 10 μm.)

We hypothesized that increased parenchymal IgG deposition after multiple GAS infections could be due to increased transcellular transport across the BBB. To address this question, we administered i.v. either a fluorescently labeled exogenous mouse IgG or albumin-Alexa 594 and measured their levels in the OB parenchyma and blood vessels, respectively, in GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice 30 min after circulation. The fluorescent i.v.-injected IgG was twofold higher in brains of GAS-infected RORγt+/− compared to RORγt−/− mice (Fig. 2 G–J). In addition, small-caliber vessels from GAS-infected RORγt+/− brains had a threefold higher number of albumin-filled vesicles, indicative of increased caveolar transcytosis, compared to those from either GAS-infected RORγt−/− brains or healthy controls (Fig. 2 L–O). Overall, these data show that Th17 lymphocytes facilitate the entry of antibodies into the brain across the BBB during postinfectious BGE by up-regulation of caveolar transcytosis.

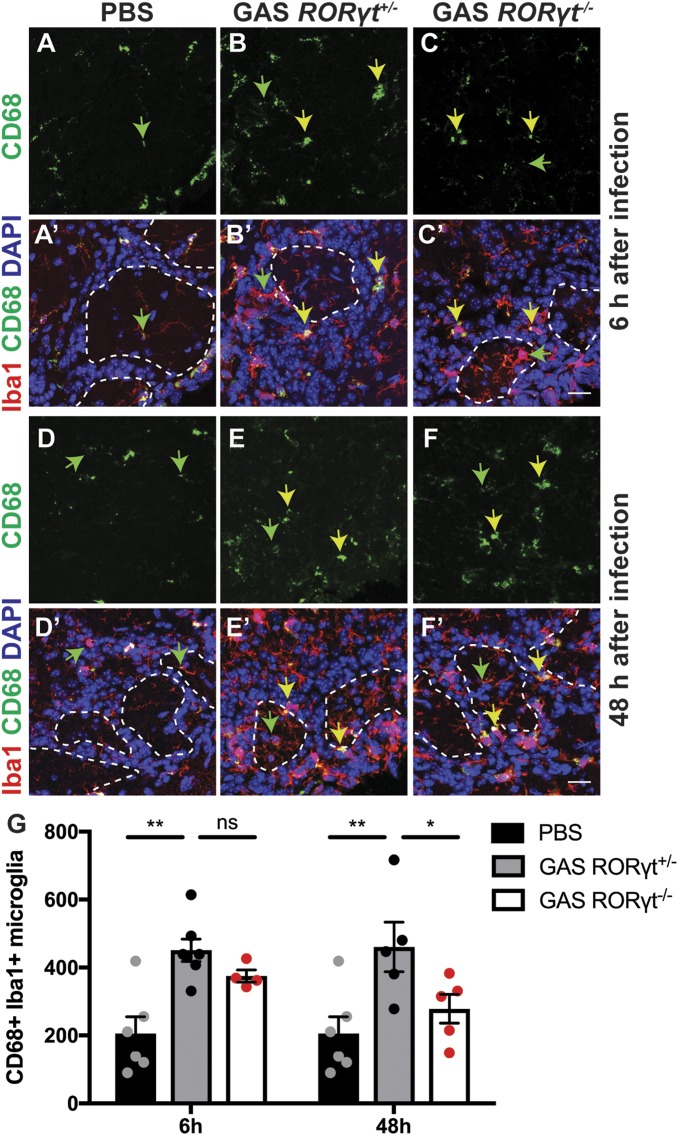

Microglial Activation Is Attenuated in Th17 Cell-Deficient Mice Undergoing Postinfectious BGE.

We next examined whether loss of Th17 lymphocytes affects activation of microglia and infiltration of peripheral macrophages after multiple GAS infections. We counted CD68+ Iba1+ activated microglia/macrophages in the glomerular layer of PBS control, GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− OBs 6 and 48 h after the final infection. Relative to PBS controls, we find a twofold increase in activated microglia in GAS-infected RORγt+/− brains (Fig. 3 A–B′, D–E′, and G), but no significant change in microglial activation and macrophage infiltration in GAS-infected RORγt−/− brains after 48 h (Fig. 3 C, C′, F, F′, and G). Thus, infiltrating Th17 cells promote prolonged activation of microglia or coinfiltration of peripheral macrophages in postinfectious BGE.

Fig. 3.

Th17 lymphocytes are required for persistent microglial activation within the OB after multiple GAS infections. (A–F′) Immunofluorescence for CD68 (green), Iba1 (red), and DAPI (blue) in olfactory bulbs (OBs) of PBS, GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice at 6 and 48 h after the last infection. Microglia in PBS-inoculated mice contain small CD68+ lysosomes (green arrows). After GAS infections, microglia or peripheral macrophages in RORγt+/− mice and, to a lesser extent, in GAS RORγt−/− mice at 6 but not 48 h after infection show large CD68+ lysosomal vesicles (yellow arrows). (G) Quantification of Iba1+ CD68+ activated microglia in the glomerular layer at 6 and 48 h after the last infection. These data show that microglia activation is significantly reduced in RORγt−/− mice at 48 h after the last infection. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6 PBS, n = 7 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 4 GAS RORγt−/− mice at 6 h after the last infection, n = 5 GAS RORγt+/−, n = 5 GAS RORγt−/− mice at 48 h after the last infection [**P = 0.0015, PBS vs. GAS RORγt+/− (6 h); P = 0.4956 [non significant (NS)], GAS RORγt+/− (6 h) vs. GAS RORγt−/− (6 h); **P = 0.0024, PBS vs. GAS RORγt+/− (48 h); P = 0.0464, GAS RORγt+/− (48 h) vs. GAS RORγt−/− (48 h) by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc correction for multiple comparisons]). (Scale bars, 20 μm.)

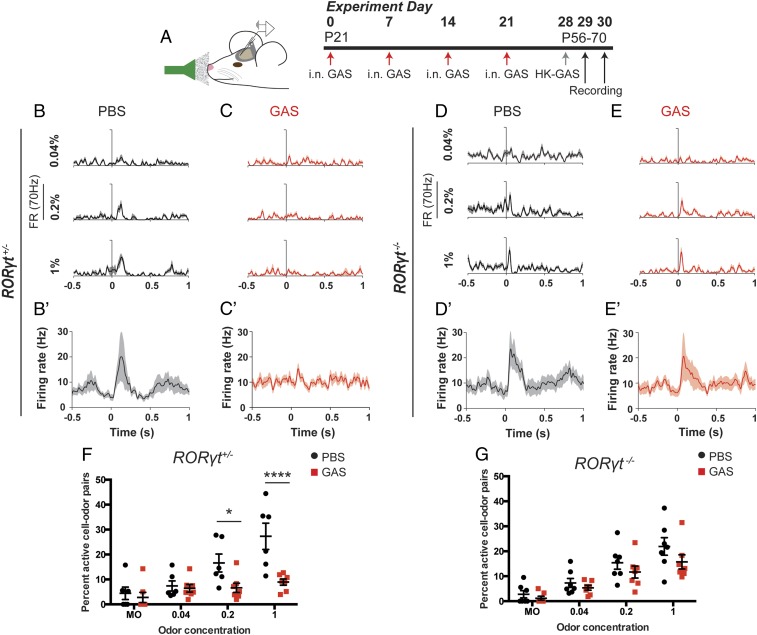

Persistent Olfactory Circuit and Odor-Processing Deficits Arise after Multiple GAS Infections and Depend in Part on Th17 Lymphocytes.

Olfactory neurons that provide sensory information to the OB are particularly vulnerable to inflammatory injury because their cell bodies reside within the nasal mucosa outside the CNS. To address whether reduction in vGluT2 expression in OB glomeruli after multiple GAS infections (22) depends on Th17 cells, we analyzed vGluT2 expression at olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) terminals and glutamate decarboxylase 67 (GAD67), an enzyme expressed by GABAergic local inhibitory interneurons in the OB glomeruli of GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice at 6 and 48 h after the last infection. We find that glomerular vGluT2 expression is reduced in GAS-infected mice, regardless of their genotype, compared to PBS controls at 6 h after infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C″ and F). Surprisingly, vGluT2 expression within glomeruli was restored by 48 h after the final infection in both genotypes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 D–E″ and F).

The transient loss of vGluT2 expression in OB glomeruli raises the question whether olfactory function is impaired persistently in GAS-infected mice. First, we used a habituation–dishabituation behavioral paradigm, which leverages a mouse’s curiosity for new olfactory stimuli. Mice are presented with an unscented Q-tip, which they first investigate by sniffing but then rapidly lose interest at subsequent presentations of the same stimulus (habituation). However, if the Q-tip is impregnated with an odor, mice initially investigate the novel odor (dishabituation) indicating odor detection, but they rapidly habituate to subsequent presentations of the same odor. Mice will reinvestigate if a different odor is presented, measuring odor discrimination. All mice actively investigate an unscented Q-tip but then rapidly lose interest (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D) (31). PBS control mice show both intact odor detection and discrimination. In contrast, GAS-infected mice show both impaired odor detection and odor discrimination at 6 h after the last infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D), consistent with reduced vGluT2 expression in glomeruli (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C″ and F). Importantly, all treatment groups had similar baseline locomotor activity, suggesting that odor deficits were not due to sickness or other behavioral changes induced by multiple GAS infections.

To determine whether there are persistent deficits in olfactory processing, we recorded odor-evoked spiking activity in populations of mitral/tufted (M/T) neurons within the OB in awake, head-fixed GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice at 48 h after the last infection (32, 33) (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). Individual M/T neurons are either activated or suppressed by different monomolecular odorants (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 E and E′) as they relay the information to various regions of the olfactory cortex. Single M/T neurons show robust odor responses in both RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− PBS control mice (Fig. 4 B, B′, D, and D′ and SI Appendix, Fig. S5E). In contrast, GAS-infected RORγt+/− mice show a striking absence of odor responses in M/T neurons, whereas GAS-infected RORγt−/− mice show only a partial deficit in single M/T neuronal responses (Fig. 4 C, C′, E, and E′ and SI Appendix, Fig. S5E′), indicating that physiological deficits are partially regulated via a Th17 cell-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 4.

Persistent olfactory processing deficits in GAS-infected mice require Th17 lymphocytes. (A) Experimental design for electrophysiological recordings using a 32-channel probe lowered into the mitral cell layer of the OB. The timeline denotes a final heat-killed GAS (HK-GAS) inoculation instead of live GAS infections prior to recordings. (B–F) Representative unit peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) in response to ethyl butyrate at three different odor concentrations (n = 15 trials per odor-concentration stimulus) and (B′–E′) mean PSTH averaged across six monomolecular odors. PSTHs are aligned to the beginning of the first inhalation after odor onset, defined as t = 0. Odor stimuli were presented for 1 s. There is no response to odor stimuli in GAS-infected RORγt+/− mice compared to PBS controls (B and C). However, there is some response to odor stimuli in GAS-infected RORγt−/− mice compared to PBS controls (D and E). (F and G) Fraction of total units that respond by either significant activation or suppression to odors, including mineral oil (MO), at each concentration for (F) RORγt+/− and (G) RORγt−/− mice infected with PBS or GAS. There is no response to increasing concentrations of odor stimuli in GAS-infected RORγt+/− mice, but there is a partial response in RORγt−/− mice. Data were collected from n = 120 neurons from 6 recordings in 4 PBS RORγt+/− mice; n = 140 neurons from 7 recordings in 4 PBS RORγt−/− mice; n = 130 neurons from 7 recordings in 5 GAS RORγt+/− mice; and n = 144 neurons from 7 recordings in 5 GAS RORγt−/− mice; represented as mean ± SEM. (F) MO, P = 0.9863 (NS); 0.02%, P = 0.9987 (NS); 0.4%, *P = 0.0449; 1% ****P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test. (G) MO, P = 0.9785 (NS); 0.02%, P = 0.9565 (NS); 0.4%, 0.6721 (NS); 1%, P = 0.204 (NS) by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple-comparisons test.

We then analyzed M/T neuronal responses over a 25-fold range of odor concentration from 0.04 to 1% (vol/vol) odor dilution and a mineral oil control stimulus. PBS control mice show a systematic, concentration-dependent increase in the fraction of responsive M/T neurons, regardless of the genotype (Fig. 4 F and G and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 E and E′). Odor-evoked responses are somewhat attenuated in GAS-infected RORγt−/− mice; in contrast, neuronal responses across all odor concentrations are abolished (equivalent to mineral oil controls) in GAS-infected RORγt+/− mice (Fig. 4 F and G) with no change in baseline firing rates among all groups (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Taken together, these findings suggest that Th17 lymphocytes are partially responsible for much of the persistent odor-processing deficits that ensues after GAS infections.

B Cells Are Absent from the Brain Parenchyma after Multiple GAS Infections.

B cells and plasma cell play an important role in the humoral response after GAS infections (34). Although the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid of AE patients indicates intrathecal (i.e., CNS) antibody synthesis by plasma cells (5), it is unclear what role B cells and plasma cells play in the intranasal GAS mouse model. We first tested whether antibodies against GAS proteins were present in sera from GAS-infected RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice. Sera from both genotypes contained equivalent amounts of GAS-specific antibodies, indicating that Th17 deficiency does not affect GAS-directed antibody production in surviving mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). We then examined the presence of B and plasma cells in the brain. After multiple GAS infections, B220+ B cells and CD138+ plasma cells are present in the olfactory mucosa and brain meninges of both RORγt+/− and RORγt−/− mice; however, they are absent from the brain parenchyma (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A–D′). Although multiple GAS infections induce distinct T cells subtypes into the brain and NALT (Fig. 1 B–F and K–N and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 I and J′), the fractions of B cells and plasma cells in the brains were very low by flow cytometry, independent of the genotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 E–H), Importantly, these cells were abundant in the NALTs and spleens of both genotypes after multiple GAS infections, indicating no B or plasma cell deficits in Th17-deficient mice (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 A and B and S7 E–H). These findings suggest that B or plasma cells do not play a major role in neurovascular dysfunction or antibody deposition into the CNS in the animal model.

Discussion

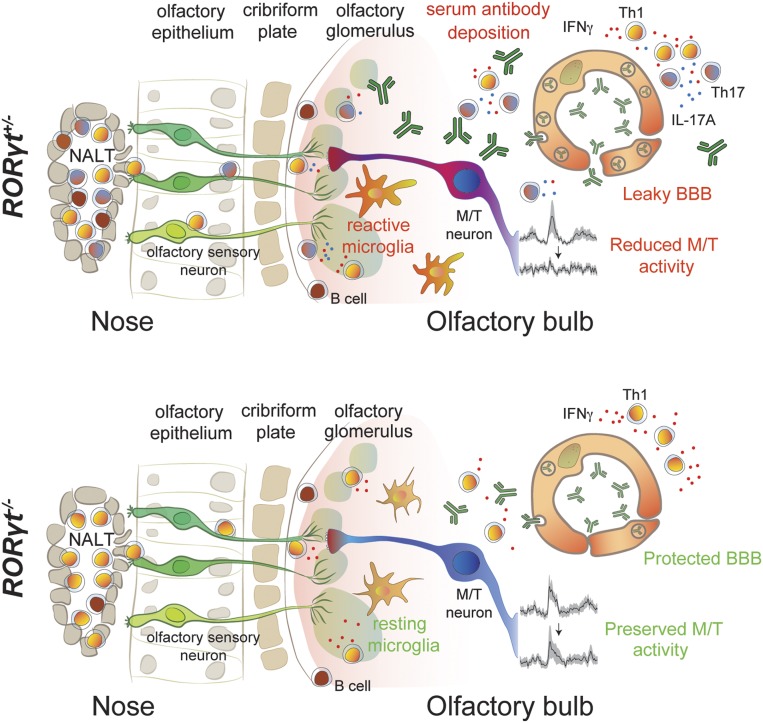

AE triggering acute neurological and psychiatric symptoms are now widely recognized and their CNS autoantigens have been validated (1–3, 10), yet the mechanisms that underlie disease pathogenesis are poorly understood (1, 35–37) and how autoantibodies breach the BBB remains obscure (4). Although human studies have shown peripheral CD3+ T cell infiltration in brains from both SC and AE patients (19, 20) and we have found that CD4+ T cell brain infiltration is associated with vascular pathology and synaptic defects in a mouse model for postinfectious BGE (22), the contribution of cellular adaptive immune mechanisms to disease pathogenesis is ill-defined. Here, we find that Th17 lymphocytes are required for autoantibody transport across the BBB, microglial activation/macrophage infiltration, and persistent neural circuit functional defects in mice (Fig. 5). We discuss the role of Th17 lymphocytes in postinfectious BGE, compare and contrast our findings to other CNS autoimmune diseases (MS/EAE), and consider potential implications for human AE.

Fig. 5.

Th17 lymphocytes are critical for neurovascular, neuroinflammatory, and neurophysiological deficits in postinfectious BGE. Recurrent GAS infections of the olfactory mucosa in mice cause production and accumulation of Th17 and Th1 lymphocytes in the NALT and OE. T cells then migrate along sensory axons to the olfactory bulb (OB). IL-17A, IFN-γ, or other proinflammatory cytokines produced by Th17 lymphocytes induce activation of microglia. Inflammatory cytokines secreted by either Th17 lymphocytes or reactive microglia promote blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakdown via degradation of TJ proteins and up-regulation of vesicular transport of antibodies. This enables deposition of antibodies into the CNS parenchyma and causes impaired olfactory processing in both olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) and mitral/tufted (M/T) neurons in the OB. In RORγt−/− mice, a predominantly Th1 cell population is generated in the NALT/OE, which then enters the OB. Without infiltrating Th17 lymphocytes, transcytosis across endothelial cells remains low, limiting the entry of antibodies into the CNS. In addition, microglia activation/macrophage infiltration is reduced in the CNS and processing of odor stimuli within OSNs and M/T neurons is partially preserved in the absence of Th17 lymphocytes. B and plasma cells are present only in the meninges of both genotypes after GAS infections.

Th17 lymphocytes mediate host-defensive mechanisms to various extracellular bacterial mucosal infections such as GAS (34) but also underlie pathogenesis for many autoimmune diseases (38). Although Th17 cells are dispensable for disease initiation, they either promote progression or increase severity of many autoimmune diseases (39, 40). As in EAE, Th17 lymphocytes secrete various cytokines that are critical to permeabilize the BBB (41) and permit antibody entry in postinfectious BGE (Fig. 5). Sustained BBB leakage to small molecules in RORγt−/− mice may be due to Th1 lymphocytes secreting IFN-γ, a cytokine known to induce BBB leakage and activate microglia both in vitro and in vivo, although less effectively than IL-17A (17, 42). Our work provides evidence that Th17-dependent mechanisms may regulate transcytosis in CNS endothelial cells to permit IgG entry (Figs. 2 and 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). IFNγ and TNFα, two cytokines that are secreted by Th17 lymphocytes (41), can stimulate transcytosis of albumin-Alexa 594 in cultured primary mouse brain endothelial cells via a caveolar-mediated mechanism (29). Alternatively, Th17 lymphocytes may induce expression of proinflammatory cytokines from microglia or astrocytes (e.g., CCL2) as occurs in EAE (43) that promote Caveolin-1–mediated transcytosis in endothelial cells (44). Since microglial activation is reduced in the absence of Th17 cells after GAS infections (Figs. 3 and 5), the increase in BBB permeability may be induced either directly by Th17 lymphocytes or indirectly by activated microglia.

In addition to their potential roles in antigen presentation, immune defense and BBB permeability in the CNS, microglial-mediated synaptic sculpting in development (45) and disease (46) may partially explain the physiological deficits in GAS-infected RORγt+/− compared to RORγt−/− mice where microglial activation is reduced and physiology is partially rescued (Figs. 3–5). Thus, although both IL-17A+ and IFN-γ+ IL-17A+ effector T cell populations are necessary to induce the full spectrum of neuropathological consequences during postinfectious BGE, similar to their proposed roles in MS/EAE (47), we cannot exclude the possibility that Th17 cell-induced pathology may be accomplished in part by persistent microglial activation. A recent study has also shown that mature T cells are required to induce disease in a novel rodent model of anti-NMDAR autoimmune encephalitis (21). Targeting CNS Th1 and Th17 cells therapeutically may therefore mitigate the disease course in AE. In contrast to Th17 lymphocytes, B or plasma cells are not present in the CNS parenchyma after multiple GAS infections, albeit they are present in meninges in both genotypes. These findings suggest that these cells do not play a major role in neurovascular dysfunction or antibody deposition into the CNS after multiple GAS infections, as opposed to Th17 lymphocytes that drive these pathologies.

Recent studies have established anosmia as a prodromal biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease (48–50) and the presence of olfactory deficits in a subset of MS patients correlating with symptom severity (51, 52). GAS-infected mice show severe persistent physiological deficits in M/T neuronal function (Fig. 4), although vGluT2 expression within glomeruli is restored by 48 h after i.n. infections (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Reduction of vGluT2 in OSN terminals provides the most parsimonious explanation for reduced neurotransmission in M/T neurons of GAS-infected mice, but vGluT2 is also expressed in dendrites of external tufted neurons, which are the main drivers of M/T neuronal responses in vitro (53). Either OSN terminals or external tufted dendrites may have reduced vGluT2 expression, which explains odor-processing deficits after GAS infections. Whether Th17 cells impair neural circuit function directly, or indirectly via excessive microglial activation and the presence of pathogenic antibodies in the CNS, remains unclear, as these phenomena are reduced in RORγt−/− mice. We have previously shown that GAS-specific T cells are present in the brain of mice up to at least 56 d after GAS infections (22), a time course that matches the development of neurological sequelae for rheumatic fever, where symptoms of chorea do not become evident for several weeks or months after the infection has subsided (6). These persistent T cells in the brains may likely induce persistent BBB leakage or microglia activation that would permit autoantibodies to enter the brain. Future studies will determine how long these pathological or functional deficits persist after GAS infections in our mouse model, and if changes in odor processing affect more complex behaviors dependent on other olfactory brain regions (AON, piriform cortex, and amygdala).

The results presented here reinforce a multiple-hit hypothesis for poststreptococcal BGE, wherein acute neurological and/or psychiatric symptoms only arise at the intersection of several clinical states: repeated untreated (or unresolved) GAS infections that break down the immune tolerance against self-antigens leading to development of cross-reactive autoantibodies targeting the CNS, and a genetic susceptibility to autoimmunity that may explain why a subset of children develop BGE after GAS infections, a very common childhood illness (6, 11). Recurrent intranasal streptococcal, staphylococcal, or viral infections in children or young adolescents also trigger a potent Th17 immune response in the nasal mucosa or other sites where the bacteria resides in humans such as the throat, tonsils, skin, or the perianal area and may promote the entry of these cells into the CNS to initiate AE if relevant autoantibodies are present systemically (34). Thus, BBB breakdown is a necessary early step during postinfectious BGEs to allow entry of such autoantibodies into the CNS.

Our results implicating Th17 cells as critical players causing BBB leakage in rodent brains after recurrent GAS infection suggest several avenues to improve diagnostic specificity and treatment options. These include testing for cytokine profiles characteristic of a Th17 response in the CSF and sera from BGE patients, as well as incorporating dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI imaging tools to detect BBB dysfunction during disease flare-ups, similar to those used for MS and traumatic brain injury. Such improved diagnostic tools, combined with studies that examine the role of Th17 lymphocytes in human postinfectious BGE pathogenesis, will guide physicians toward more accurate diagnoses for suspected BGEs and treatments targeting Th17 lymphocytes.

Materials and Methods

Detailed descriptions of all materials and methods are provided in SI Appendix, SI Methods.

Mice.

All procedures have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) (#AAAX3452) and Duke University (#A220-15-08). Female postnatal day 21 (P21) to P28 SJL/J, RORγt+/GFP and RORγtGFP/GFP mice [B6.129P2(Cg)-Rorctm2Litt/J; Jackson Laboratory] received five weekly GAS infections as described (22). SJL/J mice were immunized s.c. as described (25, 26).

Flow Cytometry.

Mice were perfused in ice-cold sterile PBS. Lymphocytes were isolated as described (29). For cytokine staining, cells were stimulated in vitro with 500× Cell Stimulation Mixture (eBioscience; 00-4975-03) for 4 h, treated with CD16/CD32 Fc block for 1 h (BD Pharmingen; 553141; 1:200), and stained for various surface antigens (see SI Appendix for details). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen; 554714), and stained for intracellular cytokines (see SI Appendix for details). For Treg analyses, cells were stained for the same surface antigens without restimulation in vitro, and then stained for transcription factors (see SI Appendix for details). Flow analysis was performed on a BD FACS Celesta (Columbia Stem Cell Initiative Flow Cytometry Core).

Immunofluorescence, Cell Quantification, and BBB Imaging.

Mice were perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were processed, sectioned, stained, and imaged as described (see refs. 22 and 28–30 and SI Appendix). BBB permeability was assessed with three tracers (biocytin-tetramethylrhodamine [biocytin-TMR] [Thermo Fisher; T12921], albumin-Alexa 594 [Thermo Fisher; A13101], and mouse IgG [Bio-Rad; MCA1209A488]), as described (22, 28–30). Brain imaging was performed with Zeiss AxioImager fluorescent microscope or a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope.

Western Blotting.

Mouse brains were collected after perfusion with PBS and homogenized in lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein levels were quantified by LI-COR fluorescent Western blot analysis (LI-COR) (30). Primary antibodies are described in the SI Appendix text.

Olfactory Habituation/Dishabituation Test and Electrophysiology.

Olfactory function was assessed using a habituation–dishabituation test 6 h after the final GAS infection. Mice were habituated singly to a clean empty cage in the testing room for 30 min prior to testing, and were tested in groups of two to three. Mice were allowed to investigate long-handled Q-tips treated with 10 μL of odorant (diluted 1:100) or vehicle (water) for 2 min per trial, with ∼1 min between trials. Extracellular unit recordings and analyses of odor-evoked spiking activity in olfactory bulb M/T neurons in awake, head-fixed mice were performed as described (32, 33). Briefly, after four inoculations with PBS or live GAS, mice were surgically fitted with a custom-machined head plate to allow for awake, head-fixed recording from the OB. Mice were then inoculated with an equivalent dose of PBS or HK-GAS, and recordings were performed in a liquid dilution, 10-channel olfactometer 48 h after the final infection (see SI Appendix for more details). Behavioral and physiological analyses were performed blind to the genotype.

Data Availability.

All data are included in the manuscript and SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.P.P., C.R.W., D.A., and T.C. are supported by grants from the NIH/National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (R01 MH112849 and R56 MH109987). D.A. is also supported by the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS107344) and the Leducq Foundation (15CDV-02), and D.A. and T.C. are partially supported by unrestricted gifts from John. F. Castle and Newport Equities LLC to the Division of Cerebrovascular Diseases and Stroke, Department of Neurology, CUIMC. K.A.B. and K.M.F. are supported by NIH/NIMH (R01 MH112849) and NIH/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC015525 and R01 DC016782). We thank Holly and Mark Kerslake from Newport Equities LLC for generous financial support through an unrestricted gift, which has enabled much of our work on the animal model for GAS-induced BGE, as well as PANDAS Network for its donation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1911097117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dalmau J., Graus F., Antibody-mediated encephalitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 840–851 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Coevorden-Hameete M. H., de Graaff E., Titulaer M. J., Hoogenraad C. C., Sillevis Smitt P. A., Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying anti-neuronal antibody mediated disorders of the central nervous system. Autoimmun. Rev. 13, 299–312 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leypoldt F., Armangue T., Dalmau J., Autoimmune encephalopathies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1338, 94–114 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platt M. P., Agalliu D., Cutforth T., Hello from the other side: How autoantibodies circumvent the blood-brain barrier in autoimmune encephalitis. Front. Immunol. 8, 442 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mader S., Brimberg L., Diamond B., The role of brain-reactive autoantibodies in brain pathology and cognitive impairment. Front. Immunol. 8, 1101 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham M. W., Molecular mimicry, autoimmunity, and infection: The cross-reactive antigens of group A streptococci and their sequelae. Microbiol. Spectr. 7, GPP3-0045-2018 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams K. A., Swedo S. E., Post-infectious autoimmune disorders: Sydenham’s chorea, PANDAS and beyond. Brain Res. 1617, 144–154 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orefici G., Cardona F., Cox C. J., Cunningham M. W., “Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS)” in Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations, J. J. Ferretti, D. L. Stevens, V. A. Fischetti, Eds. (University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, OK, 2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333433/. [PubMed]

- 9.Swedo S. E., et al. , Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: Clinical description of the first 50 cases. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 264–271 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinmaz N., et al. , Autoantibodies in movement and psychiatric disorders: Updated concepts in detection methods, pathogenicity, and CNS entry. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1351, 22–38 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutforth T., DeMille M. M., Agalliu I., Agalliu D., CNS autoimmune disease after Streptococcus pyogenes infections: Animal models, cellular mechanisms and genetic factors. Future Neurol. 11, 63–76 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dale R. C., et al. , Antibodies to surface dopamine-2 receptor in autoimmune movement and psychiatric disorders. Brain 135, 3453–3468 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirvan C. A., Swedo S. E., Snider L. A., Cunningham M. W., Antibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in behavior and movement disorders. J. Neuroimmunol. 179, 173–179 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox C. J., et al. , Brain human monoclonal autoantibody from Sydenham chorea targets dopaminergic neurons in transgenic mice and signals dopamine D2 receptor: Implications in human disease. J. Immunol. 191, 5524–5541 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garvey M. A., Snider L. A., Leitman S. F., Werden R., Swedo S. E., Treatment of Sydenham’s chorea with intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, or prednisone. J. Child Neurol. 20, 424–429 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacevic M., Grant P., Swedo S. E., Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of twelve youths with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 25, 65–69 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daneman R., Engelhardt B., Brain barriers in health and disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 107, 1–3 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liebner S., et al. , Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 135, 311–336 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colony H. S., Malamud N., Sydenham’s chorea; a clinicopathologic study. Neurology 6, 672–676 (1956). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer J., Bien C. G., Neuropathology of autoimmune encephalitides. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 133, 107–120 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones B. E., et al. , Autoimmune receptor encephalitis in mice induced by active immunization with conformationally stabilized holoreceptors. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaaw0044 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dileepan T., et al. , Group A Streptococcus intranasal infection promotes CNS infiltration by streptococcal-specific Th17 cells. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 303–317 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanov I. I., et al. , The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dileepan T., et al. , Robust antigen specific Th17 T cell response to group A Streptococcus is dependent on IL-6 and intranasal route of infection. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002252 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brimberg L., et al. , Behavioral, pharmacological, and immunological abnormalities after streptococcal exposure: A novel rat model of Sydenham chorea and related neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 2076–2087 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman K. L., Hornig M., Yaddanapudi K., Jabado O., Lipkin W. I., A murine model for neuropsychiatric disorders associated with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. J. Neurosci. 24, 1780–1791 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rostami A., Ciric B., Role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of CNS inflammatory demyelination. J. Neurol. Sci. 333, 76–87 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knowland D., et al. , Stepwise recruitment of transcellular and paracellular pathways underlies blood-brain barrier breakdown in stroke. Neuron 82, 603–617 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutz S. E., et al. , Caveolin1 is required for Th1 cell infiltration, but not tight junction remodeling, at the blood-brain barrier in autoimmune neuroinflammation. Cell Rep. 21, 2104–2117 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengfeld J. E., et al. , Endothelial Wnt/β-catenin signaling reduces immune cell infiltration in multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E1168–E1177 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Root C. M., Denny C. A., Hen R., Axel R., The participation of cortical amygdala in innate, odour-driven behaviour. Nature 515, 269–273 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolding K. A., Franks K. M., Recurrent cortical circuits implement concentration-invariant odor coding. Science 361, eaat6904 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bolding K. A., Franks K. M., Complementary codes for odor identity and intensity in olfactory cortex. eLife 6, e22630 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham M. W., Rheumatic fever, autoimmunity, and molecular mimicry: The streptococcal connection. Int. Rev. Immunol. 33, 314–329 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haselmann H., et al. , Human autoantibodies against the AMPA receptor subunit GluA2 induce receptor reorganization and memory dysfunction. Neuron 100, 91–105.e9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petit-Pedrol M., et al. , LGI1 antibodies alter Kv1.1 and AMPA receptors changing synaptic excitability, plasticity and memory. Brain 141, 3144–3159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diamond B., Honig G., Mader S., Brimberg L., Volpe B. T., Brain-reactive antibodies and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31, 345–385 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang W., Kolls J. K., Zheng Y., The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity 28, 454–467 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee G. R., The balance of Th17 versus Treg cells in autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, E730 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stadhouders R., Lubberts E., Hendriks R. W., A cellular and molecular view of T helper 17 cell plasticity in autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 87, 1–15 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner C. A., Roqué P. J., Goverman J. M., Pathogenic T cell cytokines in multiple sclerosis. J. Exp. Med. 217, e20190460 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oshima T., et al. , Interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 reciprocally regulate endothelial junction integrity and barrier function. Microvasc. Res. 61, 130–143 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prajeeth C. K., et al. , Effectors of Th1 and Th17 cells act on astrocytes and augment their neuroinflammatory properties. J. Neuroinflammation 14, 204 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stamatovic S. M., Keep R. F., Wang M. M., Jankovic I., Andjelkovic A. V., Caveolae-mediated internalization of occludin and claudin-5 during CCL2-induced tight junction remodeling in brain endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19053–19066 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schafer D. P., et al. , Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 74, 691–705 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hong S., et al. , Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352, 712–716 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovett-Racke A. E., Yang Y., Racke M. K., Th1 versus Th17: Are T cell cytokines relevant in multiple sclerosis? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1812, 246–251 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devanand D. P., Olfactory identification deficits, cognitive decline, and dementia in older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 24, 1151–1157 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva M. M. E., Mercer P. B. S., Witt M. C. Z., Pessoa R. R., Olfactory dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease systematic review and meta-analysis. Dement. Neuropsychol. 12, 123–132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dhilla Albers A., et al. , Episodic memory of odors stratifies Alzheimer biomarkers in normal elderly. Ann. Neurol. 80, 846–857 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciurleo R., et al. , Olfactory dysfunction as a prognostic marker for disability progression in multiple sclerosis: An olfactory event related potential study. PLoS One 13, e0196006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shin T., Kim J., Ahn M., Moon C., Olfactory dysfunction in CNS neuroimmunological disorders: A review. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 3714–3721 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gire D. H., et al. , Mitral cells in the olfactory bulb are mainly excited through a multistep signaling path. J. Neurosci. 32, 2964–2975 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and SI Appendix.