Abstract

Background

Specific clinical interventions are needed to reduce wrong‐site surgery, which is a rare but potentially disastrous clinical error. Risk factors contributing to wrong‐site surgery are variable and complex. The introduction of organisational and professional clinical strategies have a role in minimising wrong‐site surgery.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of organisational and professional interventions for reducing wrong‐site surgery (including wrong‐side, wrong‐procedure and wrong‐patient surgery), including non‐surgical invasive clinical procedures such as regional blocks, dermatological, obstetric and dental procedures and emergency surgical procedures not undertaken within the operating theatre.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register (January 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2014), MEDLINE (June 2011 to January 2014), EMBASE (June 2011 to January 2014), CINAHL (June 2011 to January 2014), Dissertations and Theses (June 2011 to January 2014), African Index Medicus, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences database, Virtual Health Library, Pan American Health Organization Database and the World Health Organization Library Information System. Database searches were conducted in January 2014.

Selection criteria

We searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised controlled trials, controlled before‐after studies (CBAs) with at least two intervention and control sites, and interrupted‐time‐series (ITS) studies where the intervention time was clearly defined and there were at least three data points before and three after the intervention. We included two ITS studies that evaluated the effectiveness of organisational and professional interventions for reducing wrong‐site surgery, including wrong‐side and wrong‐procedure surgery. Participants included all healthcare professionals providing care to surgical patients; studies where patients were involved to avoid the incorrect procedures or studies with interventions addressed to healthcare managers, administrators, stakeholders or health insurers.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assesses the quality and abstracted data of all eligible studies using a standardised data extraction form, modified from the Cochrane EPOC checklists. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

In the initial review, we included one ITS study that evaluated a targeted educational intervention aimed at reducing the incidence of wrong‐site tooth extractions. The intervention included examination of previous cases of wrong‐site tooth extractions, educational intervention including a presentation of cases of erroneous extractions, explanation of relevant clinical guidelines and feedback by an instructor. Data were reported from all patients on the surveillance system of a University Medical centre in Taiwan with a total of 24,406 tooth extractions before the intervention and 28,084 tooth extractions after the intervention. We re‐analysed the data using the Prais‐Winsten time series and the change in level for annual number of mishaps was statistically significant at ‐4.52 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐6.83 to ‐2.217) (standard error (SE) 0.5380). The change in slope was statistically significant at ‐1.16 (95% CI ‐2.22 to ‐0.10) (SE 0.2472; P < 0.05).

This update includes an additional study reporting on the incidence of neurological WSS at a university hospital both before and after the Universal Protocol’s implementation. A total of 22,743 patients undergoing neurosurgical procedures at the University of Illionois College of Medicine at Peoria, Illinois, United States of America were reported. Of these, 7286 patients were reported before the intervention and 15,456 patients were reported after the intervention. The authors found a significant difference (P < 0.001) in the incidence of WSS between the before period, 1999 to 2004, and the after period, 2005 to 2011. Similarly, data were re‐analysed using Prais‐Winsten regression to correct for autocorrelation. As the incidences were reported by year only and the intervention occurred in July 2004, the intervention year 2004 was excluded from the analysis. The change in level at the point the intervention was introduced was not statistically significant at ‐0.078 percentage points (pp) (95% CI ‐0.176 pp to 0.02 pp; SE 0.042; P = 0.103). The change in slope was statistically significant at 0.031 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.058; SE 0.012; P < 0.05).

Authors' conclusions

The findings of this update added one additional ITS study to the previous review which contained one ITS study. The original review suggested that the use of a specific educational intervention in the context of a dental outpatient setting, which targets junior dental staff using a training session that included cases of wrong‐site surgery, presentation of clinical guidelines and feedback by an instructor, was associated with a reduction in the incidence of wrong‐site tooth extractions. The additional study in this update evaluated the annual incidence rates of wrong‐site surgery in a neurosurgical population before and after the implementation of the Universal Protocol. The data suggested a strong downward trend in the incidence of wrong‐site surgery prior to the intervention with the incidence rate approaching zero. The effect of the intervention in these studies however remains unclear, as data reflect only two small low‐quality studies in very specific population groups.

Keywords: Humans; Dental Staff; Interrupted Time Series Analysis; Medical Errors; Medical Errors/prevention & control; Neurosurgical Procedures; Neurosurgical Procedures/adverse effects; Risk Factors; Surgical Procedures, Operative; Surgical Procedures, Operative/adverse effects; Tooth Extraction; Tooth Extraction/adverse effects

Plain language summary

Interventions for reducing wrong‐site surgery

Wrong‐site surgery is a rare, but serious event that can have substantial consequences for patients and healthcare providers. It occurs when a surgical or invasive procedure is undertaken on the wrong body part, wrong patient, or the wrong procedure is performed. A number of interventions to reduce surgical error or prevent WSS, mainly involving pre‐operative verification, such as the development of Universal Protocol, site marking and 'time‐out' procedures have been proposed over recent years. This updated review contains two interrupted‐time‐series (ITS) studies (studies in which data are collected at multiple time points before and after an intervention), one from the original review, which evaluated a targeted educational intervention aimed at reducing the incidence of wrong‐site surgery, and which was found to reduce its incidence. An additional study evaluated the incidence of wrong‐site surgery before and after the introduction of the Universal Protocol, however the relevance of these findings regarding the impact of the intervention is unclear given that prior to its introduction, the incidence was decreasing due to other unclear factors. Overall, this review now contains two studies, of relatively low quality evidence, on very specific populations and their generalisability to a larger audience is low.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Educational training programme to prevent wrong‐site tooth extraction | ||||

|

Patient or population: Dental patients requiring tooth extraction Settings: Outpatient department of a university hospital, Taiwan Intervention: Educational training programme (Professional intervention) Comparison: Not applicable | ||||

| Outcomes | Change in level/slope | No of studies (no of extractions) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Annual incidence rates of wrong‐site tooth extraction | Change in level: ‐4.52%; 95% CI ‐6.83% to ‐2.21%; SE 0.53; P < 0.05 Change in slope: ‐1.16; 95% CI ‐2.22 to ‐0.10; SE 0.24; P < 0.05 |

1 ITS study (24,406 tooth extractions before intervention; 28,084 after intervention) | Low1 | Data re‐analysed |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||

1. Quality of the evidence: findings of the included study were from a single institution and were specific to the individual patient population. Therefore, the generalisability and applicability of the results was questionable with the need for caution to be exercised in applying the results to other settings. This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different is high. CI: confidence interval; ITS: interrupted time series; SE: standard error.

2.

| Implementation of Universal Protocol | ||||

|

Patient or population: Patients having cranial or spinal neurosurgery Settings: Inpatients at the Department of Neurosurgery, University of Illinois College of Medicine, Peoria Intervention: Implementation of the Universal Protocol Comparison: Not applicable | ||||

| Outcomes | Change in level/slope | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Annual incidence rates of wrong‐site neurosurgery | Change in level in percentage points (pp) : ‐0.078 pp; (95% CI ‐0.176 pp to 0.02 pp); SE: 0.042; P value = 0.103 Change in slope: 0.031; (95% CI 0.004 to 0.058); SE: 0.012; P value < 0.05 |

1 ITS study (7286 operations before the intervention; 15,456 after the intervention) |

Low1 | Data re‐analysed |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1. Quality of the evidence: findings of the included study were from a single institution and were specific to the individual patient population. Therefore, the generalisability and applicability of the results was questionable with the need for caution to be exercised in applying the results to other settings. This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different is high. CI: confidence interval; ITS: interrupted time series; SE: standard error.

Background

Description of the condition

Wrong‐site surgery (WSS) is defined as surgery undertaken on the wrong person, the wrong organ or limb, wrong side or the wrong vertebral level, and can encompass invasive procedures such as regional blocks, dermatological, obstetric and dental procedures along with emergency surgical procedures not undertaken within the operating theatre. These critical errors are rare but often have major consequences for affected patients, practitioners and healthcare organisations. As a result, there has been much work done to determine which specific risk factors contribute to WSS, and if modifiable, whether WSS might be preventable (Ammerman 2006; Canale 2005; DeVine 2010; Giles 2006).

Risk factors that have been systematically identified in the literature as contributing to WSS include incorrect patient positioning or preparation of operative site; patient or family providing incorrect information; incorrect or lack of patient consent; failure to use site markings; surgeon fatigue; multiple surgeons; multiple procedures on the same patient; unusual time pressures; emergent operations; unusual patient anatomy; poor communication among, and between, treating staff, patients and patient families, inadequate radiological visualisation and morbid obesity (DeVine 2010; Longo 2012).

In recognition of this global problem, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations (JHACO 2003), in 2003, established a Universal Protocol for preventing WSS that emphasises pre‐operative verification, site marking and 'time‐out' procedures (JHACO 2003). Despite universal acceptance of such protocols, they have been criticised as being considerably complex without adding clear benefit in preventing WSS (Kwaan 2006).

How the intervention might work

In recent years, bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) have launched new safety checklists as part of a major drive to make surgery safer around the world (WHO 2009). Aspects of these checklists, such as confirmation of patient identity, site and procedure at multiple stages, and enhancing communication between team members involved in surgical cases, appear to have been designed to counter some of the risk factors that have been previously associated with WSS. Dissemination of such checklists appears to be based on evaluation of internal pilot programmes in the absence of evidence‐based recommendations supported by updated systematic reviews of current literature (WHO 2008). Nonetheless, their implementation appears to have been effective in reducing adverse surgical outcomes in certain circumstances (Haynes 2009; Treadwell 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Although the utility of measures designed to reduce WSS were analysed by Gibbs 2005, it was acknowledged by the authors that not enough time had elapsed since the introduction of the Universal Protocol or other preventive measures to determine their effectiveness conclusively. A further review reported that few studies have investigated preventive strategies for WSS, and that clinical recommendations were made on the basis of low levels of evidence (DeVine 2010). Although the study identified risk factors for WSS and provided an estimate of incidence, it did not assess the effectiveness of interventions that may help to prevent WSS. The search strategy was also limited in that it excluded non‐English‐based articles. Given the passage of time since the introduction and international acceptance of the Universal Protocol, as well as the subsequent endorsements of newer safety checklists by authoritative bodies, there is a need for a consistently updated review of the evidence of effectiveness of strategies to reduce WSS.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of organisational and professional interventions for reducing WSS (including wrong‐site, wrong‐side, wrong‐procedure and wrong‐patient surgery).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐experimental studies, controlled clinical trials (CCTs), controlled before‐after studies (CBAs) with at least two intervention sites and two control sites, and interrupted‐time‐series analyses (ITS) where the intervention time was clearly defined and there were at least three data points before and three after the intervention (EPOC 2002).

Types of participants

Participants undergoing any type of surgery; nurses or clinicians involved in delivering surgical care; operating room technicians, healthcare managers or administrators and health insurers involved in delivering surgical care. We also planned to include all studies involving healthcare professionals providing care to surgical patients; studies where patients were involved to avoid the incorrect procedures or studies with interventions addressed to healthcare managers, administrators, stakeholders or health insurers.

Types of interventions

All studies that included interventions designed to address documentation, site, procedure and patient identification, communication among healthcare team members, patients and their carers.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of WSS, including wrong‐site, wrong‐side, wrong‐procedure or wrong‐patient surgery were the primary outcomes used as criteria for including/excluded studies.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were not used as criteria for including/excluding studies. If studies included secondary outcomes, but no primary outcomes, they were not included. Secondary outcomes reported on included mortality, health service resource consumption, healthcare professional behaviour and resource burden on healthcare providers in terms of additional time taken to undertake the intervention. We also included process measures (i.e. completion rate of checklists) where available.

Search methods for identification of studies

A sensitive search strategy was designed to retrieve trials studies and relevant systematic reviews from electronic bibliographic databases.

We identified items from the following databases on January 24 2014:

MEDLINE via OVID (1948 to Jan 2014) (Appendix 1)

EMBASE via OVID (1948 to Jan 2014) (Appendix 1)

CINAHL via Ebsco (1980 to Jan 2014.) (Appendix 2)

The Cochrane Library via Wiley (2014, Issue 1 of 12) including CENTRAL, and Database of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Appendix 3)

Grey literature, which included databases such as Dissertations & Theses, African Index Medicus, etc. (Appendix 4) until 2011.

Trial Registries

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), Word Health Organization (WHO) http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (searched 24/01/2014)

ClinicalTrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) http://clinicaltrials.gov/ (searched 24/01/2014)

Search strategies were developed by M. Fiander, EPOC Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) in consultation with the authors. The final search strategies reflect an iterative development process whereby results of test strategies were screened by authors for relevance; strategies and terms yielding no relevant results were removed. Although Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and other controlled vocabulary were explored extensively, none were sufficiently useful to include.

Two methodological search filters were used to limit retrieval to appropriate study design and interventions of interest: the Cochrane RCT Sensitivity/Precision Maximizing Filter (Lefebvre 2011); and the EPOC Filter. No language restriction was applied. The search strategy was devised for the OVID MEDLINE interface and then adapted for the other databases.

Electronic searches

For this first update we searched the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations 2011 to January 2014);Ovid EMBASE (2011 to January 2014); The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 1); CINAHL, EbscoHost (2011 to February 2014) and The EPOC Specialised Register.

Searching other resources

An extensive grey literature search was conducted by C. Gabriel, assistant to the EPOC TSC up until 2011. Details of these searches and the results are available in Appendix 4. Additional studies were identified as follows: screened individual journals and conference proceedings (e.g. handsearching); reviewed reference lists of relevant systematic reviews or other publications; contacted authors of relevant studies or reviews to clarify reported published information or seek unpublished results/data; contacted researchers with expertise relevant to the review topic or EPOC interventions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

In the original review, three review authors (PM, JW and LB) reviewed the titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant trials using the selection criteria. For this first update in 2014, a similar screening process took place where records were retrieved, scanned and reviewed in a similar manner by the same authorship team. Four review authors (PM, JW, LB, CA) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all studies obtained from the search. Full‐text copies of all potentially relevant articles were retrieved for closer inspection. Further articles known to the authors were also retrieved. The review authors independently determined whether studies met the inclusion criteria (JW, LB, CA). All studies that, on examination, failed to meet the inclusion criteria were detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies. Any disagreements that arose between the review authors were resolved through discussion, or with a fourth review author (PM).

Data extraction and management

Data from the eligible studies were extracted independently by two review authors (JW, RM) using a modified version of the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group data collection checklist. Data extracted included information on study design, the intervention evaluated (including process), participants (including number in each group), setting, methods, outcomes and results.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JW, PM) independently assessed the risk of bias for the two eligible studies using the criteria described in the EPOC Group module (see additional information, assessment of methodological quality under group details) using RevMan 2011. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between two review authors. We assessed specific quality criteria for ITS studies: intervention independent of other changes, shape of the intervention effect pre‐specified, intervention unlikely to affect data collection, knowledge of allocated interventions adequately prevented during study, incomplete outcome data adequately addressed, study free from selective outcome reporting and study free from other biases. We noted each criterion as 'low risk of bias', 'unclear risk of bias' or 'high risk of bias'. If we had found RCTs or CBAs, we would have assessed them using the EPOC quality criteria for RCTs, CCTs and CBAs: allocation sequence adequately generated, allocation adequately concealed, baseline outcome measurements similar, baseline characteristics similar, incomplete outcome data adequately addressed, knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study, study adequately protected against contamination, study free from selective outcome reporting and study free from other risks of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We presented the findings in a tabular form for narrative synthesis. We reported two types of effect sizes for both included ITS studies: the change in level of the outcome immediately after the introduction of the intervention and yearly thereafter within the post‐intervention time period; and the change in the slope of the regression lines. The data were re‐analysed using the methods described in Ramsey 2003 (time series regression using Prais‐Winsten adjustment for autocorrelation).

In the event that RCTs were identified, we planned to analyse data as follows: for dichotomous outcomes, the risk ratio (RR) and the risk difference (RD) together with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI) would be calculated. For studies reporting continuous outcomes, the percentage change (i.e. the per cent improvement relative to the post‐intervention average in the control group) would also be reported. For CBA studies, we planned to report on relative effects. For dichotomous outcomes we would have reported on the RR adjusted for baseline differences in the outcome measures. For continuous variables we planned to report, if possible, on the relative change, adjusted for baseline differences in the outcome measures.

Unit of analysis issues

Re‐analysis of ITS studies

For both ITS studies, we followed the recommendation of Ramsey 2003 and computed a difference in slopes and level effect. As a unit of analysis error was present, we re‐analysed the study data using data provided in the original papers.

Re‐analysis of RCTs and CBAs with potential unit of analysis errors

Comparisons that randomise or allocate clusters (professionals or healthcare organisations) but do not account for clustering during the analysis have potential unit of analysis errors resulting in artificially extreme P values and over‐narrow CIs (Ukoumunne 1999). If we had identified any RCTs or CBAs with potential unit of analysis errors, we would have attempted to re‐analyse studies if information was available on the size/number of clusters and the value of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC), in addition to the outcome data ignoring the cluster design. Had we re‐analysed a comparison, we would have quoted the P value and annotated it with 're‐analysed'. If this was not possible, we would have reported only the point estimate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Substantial variation in the study findings was anticipated owing to various sources of heterogeneity, such as differences in the type of intervention, the type of setting (big versus small hospital, in‐hospital versus day‐surgery hospital), study design and methodological quality. If we had found studies similar enough to undertake a meta‐analysis, we would have assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic.

Data synthesis

If we had found two or more studies that were considered to be measuring essentially the same outcomes, using the same intervention in a similar population, we planned to pool the results of these studies using standard Cochrane methodology for meta‐analysis (Higgins 2011). For continuous outcome data expressed in different units across different studies, we would have calculated standardised mean differences (SMD).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

In the original search in 2012, a total of 3210 references were identified from searching the literature, of which we identified 18 potentially relevant articles and excluded 17 studies. Two further studies published after the search, known to the authors, were excluded as one was a review article (Ko 2011), and the other did not include the incidence of WSS as an outcome measure (van Klei 2012). The remaining single study by Chang 2004 met the EPOC criteria for inclusion in the review and is listed in the Characteristics of included studies.

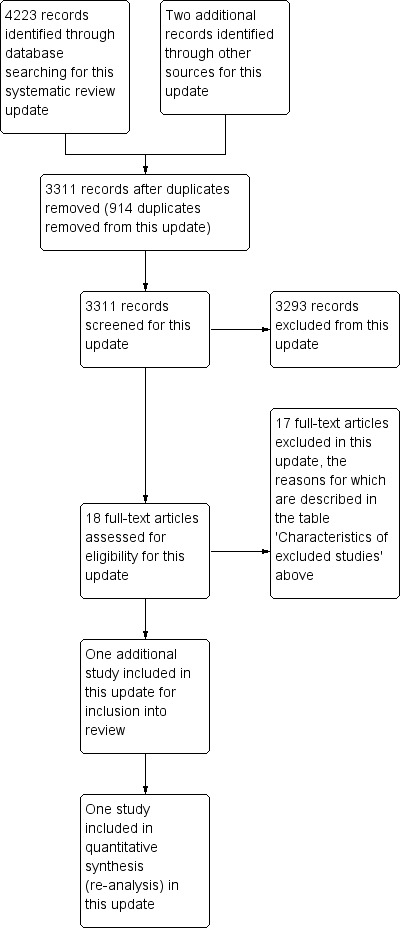

In this 2014 update, an additional 3311 reference were identified, after duplicates were removed, of which there were 18 potentially relevant articles. Two further studies published prior to the search, known to the authors, but which were not identified in the original review were also considered but excluded. One article (Vachhani 2013) met the criteria for inclusion in this review and was added to our analysis (see PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1).

1.

Search results for update 2014

Included studies

We included two studies in this review. One from the original search (Chang 2004) and one from the 2014 update search (Vachhani 2013)

In Chang 2004, data were collected from cases of wrong‐site tooth extraction during 1996 to 1998, which were used to develop a specific educational intervention that was implemented from 1999 to 2001 in a university hospital in Taiwan. Following case‐collection of instances of wrong‐site tooth extraction, surgeons and relevant personnel were interviewed within 72 hours of the mishap in each case to investigate the contribution of various factors in error production. Medical records and x‐rays were examined and additional information regarding the sites involved and related pathology was obtained. Following this a committee comprising attending dentists reviewed the information, identified factors contributing to the errors and developed clinical guidelines for preventing erroneous extraction. Subsequently, the annual incidence of erroneous extraction was compared between the pre‐intervention and intervention periods.The specific educational intervention involved targeting residents and interns from specialties within the relevant dental department and providing a training session including presentation of cases of erroneous extraction, explanation of clinical guidelines and feedback to each speciality by the instructor.The primary outcome of this study was the annual incidence rates of wrong‐site tooth extraction during 1996 to 2001 obtained by dividing the number of erroneous extractions by the total number of tooth extractions in each year.

The 2013 study by Vachhani 2013 presents wrong‐site cranial and spinal neurosurgical events recorded in the morbidity and mortality database of a single institution in the United States of America from 1991 to 2011. In 2003, the Joint Commission of the United States released the Universal Protocol for preventing wrong‐site, wrong‐procedure and wrong‐person surgery, which subsequently became mandatory for all hospitals (JHACO 2012). Data were analysed before and after implementation of this protocol at their institution in 2005. The Universal Protocol was developed in 2003 by the Joint Commission in collaboration with the American Medical Association, American Hospital Association, American College of Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Dental Association and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The three steps involved in the Universal Protocol are a pre‐operative verification process, marking of the operative site and a time out (final verification) that is performed immediately before starting the operation.The authors calculated annual incidence rates of wrong‐site surgery by determining the ratio of the number of wrong‐site surgical events per year to the total number of surgical procedures for that year.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological characteristics of the studies are shown in the Characteristics of included studies table. Whilst the Vachhani 2013 study was independent of other changes and had sufficient data points, it did not report on the reason for the number of data points pre‐ and post‐intervention, nor was there any explanation for the shape of the intervention effect. As a result, the point of analysis was also the point of the intervention. In addition, Vachhani 2013 did not report missing data, owing to an unclear risk as to whether incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed. More so, there was no distinction between the intervention and the records collected, therefore determining whether the intervention affected data collection was unclear. The data required re‐analysis. In the interrupted‐time‐series analyses (ITS) study by Chang 2004, there was a low risk of bias regarding whether the methods for data collection before and after the intervention were the same. Knowledge of the allocated interventions in both studies was prevented owing to the primary outcomes being objective. As noted in the original publication, the Chang 2004 study did not report on ARIMA (autoregressive integrated moving average) models or time series linear regression, therefore additional re‐analysis of the data could not be undertaken.

Effects of interventions

The ITS study by Chang 2004 reported on the effectiveness of an educational programme on the incidence of wrong‐site tooth extraction in an outpatient department of a university hospital. The annual incidence rates of erroneous tooth extraction for 1996, 1997 and 1998 were 0.026%, 0.025% and 0.046%, respectively. During the intervention period from 1999 to 2001, wrong‐site tooth extraction did not occur in the relevant department, revealing a significant difference in the incidence of erroneous extraction between the pre‐intervention and intervention period (P < 0.01). When the data were re‐analysed using the Prais‐Winsten time‐series regression, the change in level at each 12‐month period for annual number of mishaps was statistically significant at ‐4.52 percentage point (pp) (95% CI ‐6.83 pp to ‐2.21 pp; SE 0.53; P < 0.05). The change in slope was statistically significant at ‐1.16 (95% CI ‐2.22 to ‐0.10; SE 0.24; P < 0.05. This study did not assess any of the other secondary outcomes of interest in the review. A further summary of these results can be found in Table 3.

1. Results of included study (Chang 2004).

| Author | Study design | Intervention | Results | Notes |

| Chang 2004 | ITS | Educational training programme (professional intervention) | Rates of erroneous tooth extraction for 1996, 1997 and 1998: 0.026%, 0.025% and 0.046%. From 1999 to 2001, no erroneous tooth extraction occurred Change in level: ‐4.52%; 95% CI ‐6.83% to ‐2.21%; SE 0.53; P < 0.05 Change in slope: ‐1.16; 95% CI ‐2.22 to ‐0.10; SE: 0.24; P < 0.05 |

Data re‐analysed |

CI: confidence interval; ITS: interrupted time series.

The ITS study by Vachhani 2013 reported on the incidence of neurological WSS at a university hospital both before and after the Universal Protocol’s implementation. The authors found a significant difference (P < 0.001) in the incidence of WSS between the before period, 1999 to 2004, and the after period, 2005 to 2011. No other outcome measures were reported.The data were re‐analysed using Prais‐Winsten regression to correct for autocorrelation. As the incidences were reported by year only and the intervention occurred in July 2004, the intervention year 2004 was excluded from the analysis. The change in level at the point the intervention was introduced was not statistically significant at ‐0.078 pp (95% CI ‐0.176 pp to 0.02 pp; SE 0.042; P = 0.103). The change in slope was statistically significant at 0.031 pp (95% CI 0.004 pp to 0.058 pp; SE 0.012; P < 0.05). A further summary of these results can be found in Table 4.

2. Results of included study (Vachhani 2013).

| Author | Study design | Intervention | Results | Notes |

| Vachhani 2013 | ITS | Implementation of the Universal Protocol |

Change in level in percentage points (pp): ‐0.078 pp; (95% CI ‐0.176 pp to 0.02 pp); SE: 0.042; P value = 0.103 Change in slope: 0.031; (95% CI 0.004 to 0.058); SE: 0.012; P value < 0.05 |

Data re‐analysed |

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review aimed to assess the effectiveness of interventions to reduce wrong‐site surgery (WSS), a rare but potentially disastrous clinical error that may be preventable. The estimated range of WSS has been described as varying widely, ranging from 0.09 per 10,000 to 4.5 per 10,000 surgical procedures (DeVine 2010). We included two interrupted‐time‐series (ITS) studies.

Chang 2004 evaluated a targeted educational intervention aiming to reduce the incidence of wrong‐site tooth extractions. The intervention included examination of previous cases of wrong‐site tooth extractions, development of an education intervention including presentation of erroneous case presentations, explanation of relevant clinical guidelines and feedback by an instructor. A significant reduction in the incidence of wrong‐site tooth extraction was achieved by addressing multiple risk factors that had been previously identified in a broader surgical population.

Vachhani 2013 evaluated annual incidence rates of wrong‐site neurosurgery before and after implementation of the Universal Protocol. The data presented suggest that a strong downward trend in the incidence of WSS existed prior to the intervention (statistically significant change in slope). Any significant downward level change in the incidence rate was thus not likely as it was already close to zero, and any downward trend would also naturally flatten. This is reflected in the non‐significant change in level of incidence of WSS and significant flattening of the trend to near zero. The effect of the intervention in this study is therefore unclear.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Many features of the intervention addressed systematically identified risk factors for WSS, such as poor patient positioning; providing incorrect information to patient or patient family members; and poor communication between treating staff, patients and patient families (DeVine 2010), but it must be noted that the findings of the included studies were either from single institutions and were specific to the individual patient populations. Therefore, the generalisability and applicability of the results was questionable with the need for caution to be exercised in applying the results to other settings.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence was generally low quality because both ITS studies had some methodological shortcomings. The result of these two single studies should be interpreted with caution.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed the EPOC Group guidelines for conducting the review. However, publication bias remains a possible (but unknown) source of important bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We are not aware of any other systematic reviews that quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of either the Universal Protocol for preventing WSS (established by JHACO 2003) or the commonly used WHO Surgical Safety Checklist in reducing the incidence of WSS. A systematic review by Treadwell 2014 summarises 33 studies implementing the Universal Protocol and WHO checklist for WSS prevention. The authors conclude that while the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is associated with decreases in patient mortality and inpatient complications, no literature exists to evaluate the efficacy of these checklists in preventing wrong‐site surgery

We are aware of a number of retrospective studies that were of interest to this review. In particular, Kwaan 2006 examined a series of WSS to determine whether the Universal Protocol, emphasising pre‐operative verification, site marking and 'time‐out' practices might have been preventive. Based on the authors' retrospective judgement, rather than a prospective clinical implementation and evaluation of the protocol's effectiveness, they determined that approximately 38% of cases identified would have been unlikely to have been prevented by implementation of the Universal Protocol. While interesting, this finding is subject to the biases inherent in the retrospective judgement of the authors, and should be interpreted with caution.

Working with JCAHO, Knight 2010 developed an innovative surrogate for physically marking the surgical site as part of the Universal Protocol in the form of an "anatomic marking form". This form features the name of the procedure and the anatomical site marked on a gender‐specific diagram of the surgical site. The patient also signed this form. The authors reported a case series of over 112,500 surgical procedures during a four and a half‐year period with one documented case of WSS. In the absence of a comparison group, this study was excluded from our review; however, this study did demonstrate an adaptation in the Universal Protocol with the aim of increasing efficiency in the perioperative period.

In 2007 to 2008, Haynes 2009 conducted an international, multicentre study implementing the 19‐item WHO Surgical Safety Checklist designed to improve consistency of care and team communication. The primary end point in this study was the complication rate (including death) during hospitalisation within the first 30 days after the operation. The mortality rate in this study was 1.5% before the checklist was introduced and declined to 0.8% afterwards (P = 0.003). Inpatient complications occurred in 11% of patients at baseline and in 7% after introduction of the checklist. A retrospective cohort study conducted by van Klei 2012 on over 25,000 patients noted a reduction in crude mortality after checklist implementation, the effect of which was strongly related to checklist compliance. Similarly, between October 2007 and March 2009, deVries 2010 examined the effects on patient outcomes of another comprehensive, multidisciplinary Surgical Safety Checklist, including items such as medication, marking of the operative side and use of postoperative instructions. The rate of complications at six hospitals was compared during three‐month periods before and after the implementation of the checklist. Similar data from a control group of five hospitals were collected. Overall, results showed a significant reduction in the total number of complications from the pre‐implementation period compared to the post‐implementation period, with no change in the control hospitals. Although the checklists emphasised aspects of team communication, site marking and verification, these two studies did not specifically investigate the incidence of WSS before and after their introduction. Thus, it is not possible to conclude that the introduction of such checklists definitively reduces the incidence of this specific complication. Nonetheless, the value of checklists such as these in the process management of high‐stakes activities in both medical and non‐medical practice has been emphasised (Merry 2010), and the low‐cost, low‐risk, adaptable nature of the intervention has been highlighted (Merry 2010). Further prospective studies evaluating checklists that target the incidence of WSS as a specific complication would be very useful.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The findings of the included study by Chang 2004 suggest that there may be a benefit from implementing an educational intervention in the dental population in the context of incorrect tooth extraction; however, this is based on only one study and therefore specific results need to be viewed with appropriate caution. Similarly, the intervention targeted a number of risk factors that had been previously identified from a broader surgical context, but it must be noted that the findings of the only included study are from a single institution and are specific to the dental population. As opposed to the majority of other surgical and invasive procedures, dental extraction is a procedure associated with a need to specifically identify a structure frequently identified by a number rather than an anatomical term. Furthermore, the study may have been conducted in conscious patients in an outpatient setting. For these reasons, it is difficult to draw meaningful conclusions about the effect of similar educational interventions to prevent wrong‐patient, wrong‐procedure, or wrong‐side or ‐site surgery in other patient populations or speciality groups.

Findings from the Vachhani 2013 study suggest there may be an already existing decline in WSS events in the neurosurgical population, although the ability to generalise the findings to other populations and institutions is limited as this is a single institution study. The decline in WSS events can be attributed almost entirely to the reduction in wrong‐level spine surgery, because there was only one case of wrong‐side surgery and no cases of wrong‐patient or wrong‐case surgery. Confounding factors influencing the rates of wrong‐level spine surgery may include increasing use of intraoperative imaging and techniques such as fiducial marking. The relative rarity of WSS events, and consequent large patient numbers required, makes this difficult to examine in a prospective way. The risk of bias in study designs evaluating interventions to reduce WSS should also be considered in interpreting and applying the results of these studies to clinical practice.

Implications for research.

There are substantial difficulties in conducting research designed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce WSS. Given the difficulties associated with blinding and randomisation, as well as the significant degree of resources expended to introduce pre‐operative protocols internationally, it is difficult to conceive of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the use of pre‐operative checklists and interventions against a control group. Pre‐operative protocols and interventions designed at improving patient safety and reducing patient morbidity, such as the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, often take the form of large controlled before‐after (CBA) studies. If further research is to be conducted aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce WSS, it would likely take a similar form or alternatively, multicentre case‐control studies. Despite its potentially devastating consequences, given the relatively low incidence of WSS, large numbers of participants may be required to show a significant effect from interventions designed to reduce WSS. Consequently, multiple centres may need to consider pooling resources in order to show significant results in any proposed future research. Large CBAs or case‐control studies evaluating pre‐operative checklists, if conducted, might include as an end point the incidence of WSS, something that does not appear to have been done previously. Such research might provide further meaningful data with respect to the benefit, or lack thereof, of such interventions and balanced against the potential increase in healthcare burden and resource demand that might arise as a result of these interventions.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | New citation does not substantially change the conclusion of the original review. |

| 1 October 2014 | New search has been performed | Search repeated since last review and inclusion of additional ITS study |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sandeep Moola, Ivan Sola and Jordi Pardo for their assistance on an early draft of the protocol for this review as well as Michelle Fiander, EPOC Trials Search Co‐ordnator (TSC) for her assistance with respect to the search strategy utilised in this review. The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank Emma Tavender, Managing Editor, Australian Satellite of the Cochrane EPOC Group for her support and assistance with this review. The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Dr Steven Fowler, Department of Anaesthesia & Peri‐operative Medicine, The Alfred Hospital and Miss Heather Cleland, Victorian Adult Burns Service, The Alfred Hospital for their contributions to the original review. Finally, the authors would like to thank Maria Cumpston, Senior Training Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Editorial Unit for her assistance with respect to re‐analysis of included studies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE and EMBASE search strategies

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process and other non‐indexed citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1947 to January 2014>

1 wrong site surger*.ti,ab. [Screen all no Filters]

2 (wrong and surgery).ti. or wrong surg$.ab. 3 (wrong site or wrong person or wrong procedure or wrong patient or wrong surgical site).ti,ab. 4 (wrong side or wrong digit or wrong hip or wrong location or wrong arm or wrong leg or wrong knee or wrong ear or wrong eye or wrong finger? or wrong joint or wrong elbow or wrong foot or wrong wrist or wrong disk or wrong disc or wrong level or wrong organ or (wrong adj3 amputation)).ti,ab. [digit added 1.6] 5 ((incorrect$ or wrong$) adj5 (operating room? or wrong operating theat$)).ti,ab. [adj increased 1.6] 6 wrong location.ti,ab. and (surg$ or operating room? or operative).ti,hw. 7 universal protocol.ti,ab. 8 (side adj2 (check$ or marking or marker? or information or mix‐up or confusion)).ti,ab. 9 (site adj2 (check$ or marking or marker? or information or mix‐up or confusion)).ti,ab. [added 1.6] 10 surg$ pause.ti,ab. 11 ((surgical or surgery or operating room? or operating theater? or operating theatre?) adj3 debrief$).ti,ab. [added 1.6] 12 ((operating room or postoperative or post‐operative or pre‐surg$ or preoperativ$ or pre‐operativ$ or preprocedur$) adj3 (meeting? or briefing? or pause)).ti,ab. [Added postop 1.6] 13 ((pre‐surg$ or preoperativ$ or pre‐operativ$ or preprocedur$) adj3 (verif$ or patient confirmation or confirm$ patient or check identity or confirm identity or verif$ identity or (patient? adj2 (check$ or identity or verif$)))).ti,ab. [added verif$ 1.6] 14 ((operating room? or operating theat$) adj3 (briefing or communicat$ or briefing or verif$ or patient confirmation or confirm$ patient or check identity or confirm identity or verif$ identity)).ti,ab. 15 (surgical site adj3 (verification or verify$ or confirm$ or awareness)).ti,ab. 16 incorrect surgical site.ti,ab. 17 (surgical procedure? adj3 (verification or verify$ or wrong$ or confirm$)).ti,ab. 18 ((operating room? or operating theat$) adj4 checklist?).ti,ab. 19 ((surg$ or operating room? or operating theatre? or operating theater?) adj4 (never event? or near miss or near misses)).ti,ab. [added 1.6] 20 (surg$ adj2 (checklist? or check‐list?)).ti,ab. 21 (wrong adj4 (surgical procedur$ or operative procedure?)).ti,ab. 22 ((body or surgical or pre‐surg$ or anatomic or site) adj3 marking?).ti,ab. 23 ((preoperativ$ or pre‐operative) adj4 marking?).ti,ab. 24 patient marking.ti,ab. 25 ((operating room? or surg$) adj2 "time‐out?").ti,ab. 26 (operating room? adj2 error?).ti,ab. 27 (surg$ adj2 error?).ti,ab. 28 (aviation and surg$).ti. or (aviation adj4 surg$).ab. [Added 1.6] 29 surgical error/ [EM] 30 or/2‐28 [WSS Strategy A ‐ MEDLINE] 31 or/2‐29 [WSS Strategy A ‐ EMBASE]

32 exp Specialties, Surgical/ [e.g traumatology, neurosurgery, obstetrics, orthopaedics, etc] 33 exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/ 34 exp surgery/ or exp surgical technique/ [EM] 35 exp surgeon/ [EM] 36 (surger$ or operative procedure?).ti. 37 surgical.ti. 38 or/32‐33,36 [Surgery‐ MEDLINE] 39 or/34‐37 [Surgery ‐ EMBASE] 40 Operating Rooms/ 41 Operating Room/ [EM] 42 (operating adj2 (room? or theatre? or theater?)).ti. 43 or/40,42 [Operating Rooms ‐ MEDLINE] 44 or/41‐42 [Operating Rooms ‐ EMBASE]

45 Preoperative care/ or Perioperative Nursing/ or Perioperative care/ or Intraoperative care/ 46 perioperative care/ or preoperative care/ or perioperative period/ [EM] 47 (preoperative or intraoperative or perioperative).ti. 48 or/45,47 [Pre/Peri‐Operative Care ‐ MEDLINE] 49 or/46‐47 [Pre/Peri‐Operative Care ‐ EMBASE]

50 (wrong adj4 surgery).ti,ab. 51 skin marking.ti,ab. 52 time‐out.ti,ab. 53 call‐out?.ti,ab. 54 (pause or pausing).ti. 55 ((surg$ or team$) adj2 (pause or pausing)).ab. 56 (near miss or near misses or never event?).ti,ab. [added 1.6] 57 situational awareness.ti,ab. 58 (site adj2 (check$ or error or marker? or mix‐up or confusion or verif$)).ti,ab. 59 ((incorrect or error? or wrong$) adj3 patient).ti,ab. 60 (patient adj2 (identification or misidentif$ or identity or verification? or verif$)).ti,ab. 61 patient identification systems/ or radio frequency identification device/ 62 wristband?.ti,ab. 63 (aviation or crew resource management or teamstepps).ti,ab. 64 (team brief$ or team meeting?).ti,ab. 65 non‐technical skill?.ti,ab. 66 or/50‐65 [WSS Associated Concepts‐ MEDLINE or EMBASE]

67 *Communication/ or Communication barriers/ 68 physician‐nurse relations/ or interprofessional relations/ 69 doctor nurse relation/ [EM] 70 (team$ adj2 communicat$).ti,ab. [corrected typo 1.6] 71 interdisciplinary communication/ [EM] 72 or/67‐69 [Communication ‐ MEDLINE] 73 or/69‐71 [Communication ‐ EMBASE] 74 Checklist/ [ML or EM] 75 checklist?.ti. 76 ((safety or procedur$ or preoperat$ or identity or identification or verification or confirmation) adj4 checklist?).ab. 77 or/74‐76 [Checklist ‐ MEDLINE or EMBASE]

78 Medical Errors/ 79 medical error/ [EM] 80 (error? adj2 (reduc$ or prevent$ or improv$ or lower$)).ti. 81 (Safety/ or Safety Management/) and patient?.ti,hw. 82 *Safety/ or *Safety Management/ 83 patient safety/ [EM] 84 (clinical error? or medical error? or surgical error?).ti,ab. 85 ((unintention$ or unintend$) adj2 (harm? or event?)).ti,ab. 86 (patient? adj2 (harm or threat)).ti,ab. 87 incorrect procedure?.ti,ab. 88 or/78,80‐82,84‐87 [Med Errors/Safety ‐MEDLINE] 89 or/79‐80,83‐87 [Med Errors/Safety ‐ EMBASE]

90 intervention?.ti. or (intervention? adj6 (clinician? or collaborat$ or community or complex or DESIGN$ or doctor? or educational or family doctor? or family physician? or family practitioner? or financial or GP or general practice? or hospital? or impact? or improv$ or individuali?e? or individuali?ing or interdisciplin$ or multicomponent or multi‐component or multidisciplin$ or multi‐disciplin$ or multifacet$ or multi‐facet$ or multimodal$ or multi‐modal$ or personali?e? or personali?ing or pharmacies or pharmacist? or pharmacy or physician? or practitioner? or prescrib$ or prescription? or primary care or professional$ or provider? or regulatory or regulatory or tailor$ or target$ or team$ or usual care)).ab. 91 (hospital$ or patient?).hw. and (study or studies or care or health$ or practitioner? or provider? or physician? or nurse? or nursing or doctor?).ti,hw. 92 demonstration project?.ti,ab. 93 (pre‐post or "pre test$" or pretest$ or posttest$ or "post test$" or (pre adj5 post)).ti,ab. 94 (pre‐workshop or post‐workshop or (before adj3 workshop) or (after adj3 workshop)).ti,ab. 95 trial.ti. or ((study adj3 aim?) or "our study").ab. 96 (before adj10 (after or during)).ti,ab. 97 ("quasi‐experiment$" or quasiexperiment$ or "quasi random$" or quasirandom$ or "quasi control$" or quasicontrol$ or ((quasi$ or experimental) adj3 (method$ or study or trial or design$))).ti,ab,hw. [ML] 98 ("time series" adj2 interrupt$).ti,ab,hw. [ML] 99 (time points adj3 (over or multiple or three or four or five or six or seven or eight or nine or ten or eleven or twelve or month$ or hour? or day? or "more than")).ab. ( 100 pilot.ti. 101 Pilot projects/ [ML] 102 (clinical trial or controlled clinical trial or multicenter study).pt. [ML] 103 (multicentre or multicenter or multi‐centre or multi‐center).ti. 104 random$.ti,ab. or controlled.ti. 105 (control adj3 (area or cohort? or compare? or condition or design or group? or intervention? or participant? or study)).ab. not (controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial).pt. [ML] 106 "comment on".cm. or review.ti,pt. or randomized controlled trial.pt. [ML] 107 (rat or rats or cow or cows or chicken? or horse or horses or mice or mouse or bovine or animal?).ti. 108 exp animals/ not humans.sh. [ML] 109 *experimental design/ or *pilot study/ or quasi experimental study/ [EM] 110 ("quasi‐experiment$" or quasiexperiment$ or "quasi random$" or quasirandom$ or "quasi control$" or quasicontrol$ or ((quasi$ or experimental) adj3 (method$ or study or trial or design$))).ti,ab. [EM] 111 ("time series" adj2 interrupt$).ti,ab. [EM] 112 (or/90‐105) not (or/106‐108) [EPOC Methods Filter ML 1.9] 113 or/90‐96,99‐100,103‐104,107,109‐111 [EPOC Methods Filter EM 1.9‐2.3]

114 (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or clinical trials as topic.sh. or randomly.ab. or trial.ti. 115 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 116 "comment on".cm. or systematic review.ti. or literature review.ti. or editorial.pt. or meta‐analysis.pt. or news.pt. or review.pt. [This line is not found in Cochrane Handbook; added by TSC to exclude irrelevant publication types] 117 114 not (or/115‐116) [Cochrane RCT Filter 6.4.d Sens/Precision Maximizing] 118 30 and 117 [WSS & RCT ‐ML] 119 (30 and 112) not (or/1,118) [WSS & EPOC Filter ‐ ML]

120 ((or/38,43,48) and 66 and 117) not (or/1,118‐119) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & WSS KW & RCT ‐ ML] 121 ((or/38,43,48) and 66 and 112) not (or/1,118‐120) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & WSS KW & EPOC ‐ ML] 122 ((or/38,43,48) and 77 and 117) not (or/1,118‐121) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & Checklist & RCT ‐ ML] 123 ((or/38,43,48) and 77 and 112) not (or/1,118‐122) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & Checklist & EPOC ‐ ML] 124 ((or/38,43,48) and 88 and 117) not (or/1,118‐123) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & Med Err/Safety & RCT ‐ ML] 125 ((or/38,43,48) and 72 and 117) not (or/1,118‐123) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & Communication & RCT‐ ML] 126 (((or/38,43,48) and 72 and 112) and (collaborat$ or colleag$ or error? or intervention or mistak$ or (risk? adj2 reduc$) or safety or team?).ti,ab.) not (or/1,118‐124) [Surg/OR/Preop Care & Communication & EPOC‐ ML]

Embase Classic + Embase <1947 to January 2014>

See EM lines in Medline strategy, above:

119 31 and 118 [KW & RCT] 120 (31 and 113) not (or/1,119) [KW & EPOC] 121 ((or/39,44,49) and 66 and 118) not (or/1,119‐120) [MeSH & WSS KW & RCT] 122 ((or/39,44,49) and 66 and 113) not (or/1,119‐121) [MeSH & WSS KW & EPOC] 123 ((or/39,44,49) and 77 and 118) not (or/1,119‐122) [MeSH & Checklist & RCT] 124 ((or/39,44,49) and 77 and 113) not (or/1,119‐123) [MeSH & Checklist & EPOC] 125 ((or/39,44,49) and 89 and 118) not (or/1,119‐124) [MeSH & MedErr & RCT] 126 ((or/39,44,49) and 73 and 118) not (or/1,119‐125) [MeSH & Comm & RCT] 127 ((or/39,44,49) and 73 and 113) not (or/1,119‐126) [MeSH & Comm & EPOC]

Appendix 2. CINAHL search strategy

| CINAHL search strategy | |

| Line # | Query |

| S127 | S126 NOT S125 |

| S126 | S115 AND S64 AND S111 |

| S125 | S115 AND S64 AND S86 |

| S124 | S123 NOT S122 |

| S123 | S115 AND S79 AND S111 |

| S122 | S115 AND S79 AND S86 |

| S121 | S120 NOT S119 |

| S120 | S115 AND S68 AND S111 |

| S119 | S115 AND S68 AND S86 |

| S118 | S117 NOT S116 |

| S117 | S115 AND S58 AND S111 |

| S116 | S115 AND S58 AND S86 |

| S115 | S32 OR S35 OR S41 |

| S114 | S113 NOT S112 |

| S113 | S27 AND S111 |

| S112 | S27 AND S86 |

| S111 | S87 or S88 or S89 or S90 or S91 or S92 or S93 or S94 or S95 or S96 or S97 or S98 or S99 or S100 or S101 or S102 or S103 or S104 or S105 or S106 or S107 or S108 or S109 or S110 |

| S110 | TI ( (time points n3 over) or (time points n3 multiple) or (time points n3 three) or (time points n3 four) or (time points n3 five) or (time points n3 six) or (time points n3 seven) or (time points n3 eight) or (time points n3 nine) or (time points n3 ten) or (time points n3 eleven) or (time points n3 twelve) or (time points n3 month*) or (time points n3 hour*) or (time points n3 day*) or (time points n3 "more than") ) or AB ( (time points n3 over) or (time points n3 multiple) or (time points n3 three) or (time points n3 four) or (time points n3 five) or (time points n3 six) or (time points n3 seven) or (time points n3 eight) or (time points n3 nine) or (time points n3 ten) or (time points n3 eleven) or (time points n3 twelve) or (time points n3 month*) or (time points n3 hour*) or (time points n3 day*) or (time points n3 "more than") ) |

| S109 | TI ( (control w3 area) or (control w3 cohort*) or (control w3 compar*) or (control w3 condition) or (control w3 group*) or (control w3 intervention*) or (control w3 participant*) or (control w3 study) ) or AB ( (control w3 area) or (control w3 cohort*) or (control w3 compar*) or (control w3 condition) or (control w3 group*) or (control w3 intervention*) or (control w3 participant*) or (control w3 study) ) |

| S108 | TI ( multicentre or multicenter or multi‐centre or multi‐center ) or AB random* |

| S107 | TI random* OR controlled |

| S106 | TI ( trial or (study n3 aim) or "our study" ) or AB ( (study n3 aim) or "our study" ) |

| S105 | TI ( pre‐workshop or preworkshop or post‐workshop or postworkshop or (before n3 workshop) or (after n3 workshop) ) or AB ( pre‐workshop or preworkshop or post‐workshop or postworkshop or (before n3 workshop) or (after n3 workshop) ) |

| S104 | TI ( demonstration project OR demonstration projects OR preimplement* or pre‐implement* or post‐implement* or postimplement* ) or AB ( demonstration project OR demonstration projects OR preimplement* or pre‐implement* or post‐implement* or postimplement* ) |

| S103 | (intervention n6 clinician*) or (intervention n6 community) or (intervention n6 complex) or (intervention n6 design*) or (intervention n6 doctor*) or (intervention n6 educational) or (intervention n6 family doctor*) or (intervention n6 family physician*) or (intervention n6 family practitioner*) or (intervention n6 financial) or (intervention n6 GP) or (intervention n6 general practice*) Or (intervention n6 hospital*) or (intervention n6 impact*) Or (intervention n6 improv*) or (intervention n6 individualize*) Or (intervention n6 individualise*) or (intervention n6 individualizing) or (intervention n6 individualising) or (intervention n6 interdisciplin*) or (intervention n6 multicomponent) or (intervention n6 multi‐component) or (intervention n6 multidisciplin*) or (intervention n6 multi‐disciplin*) or (intervention n6 multifacet*) or (intervention n6 multi‐facet*) or (intervention n6 multimodal*) or (intervention n6 multi‐modal*) or (intervention n6 personalize*) or(intervention n6 personalise*) or (intervention n6 personalizing) or (intervention n6 personalising) or (intervention n6 pharmaci*) or (intervention n6 pharmacist*) or (intervention n6 pharmacy) or (intervention n6 physician*) or (intervention n6 practitioner*) Or (intervention n6 prescrib*) or (intervention n6 prescription*) or (intervention n6 primary care) or (intervention n6 professional*) or (intervention* n6 provider*) or (intervention* n6 regulatory) or (intervention n6 regulatory) or (intervention n6 tailor*) or (intervention n6 target*) or (intervention n6 team*) or (intervention n6 usual care) |

| S102 | TI ( collaborativ* or collaboration* or tailored or personalised or personalized ) or AB ( collaborativ* or collaboration* or tailored or personalised or personalized ) |

| S101 | TI pilot |

| S100 | (MH "Pilot Studies") |

| S99 | AB "before‐and‐after" |

| S98 | AB time series |

| S97 | TI time series |

| S96 | AB ( before* n10 during or before n10 after ) or AU ( before* n10 during or before n10 after ) |

| S95 | TI ( (time point*) or (period* n4 interrupted) or (period* n4 multiple) or (period* n4 time) or (period* n4 various) or (period* n4 varying) or (period* n4 week*) or (period* n4 month*) or (period* n4 year*) ) or AB ( (time point*) or (period* n4 interrupted) or (period* n4 multiple) or (period* n4 time) or (period* n4 various) or (period* n4 varying) or (period* n4 week*) or (period* n4 month*) or (period* n4 year*) ) |

| S94 | TI ( ( quasi‐experiment* or quasiexperiment* or quasi‐random* or quasirandom* or quasi control* or quasicontrol* or quasi* W3 method* or quasi* W3 study or quasi* W3 studies or quasi* W3 trial or quasi* W3 design* or experimental W3 method* or experimental W3 study or experimental W3 studies or experimental W3 trial or experimental W3 design* ) ) or AB ( ( quasi‐experiment* or quasiexperiment* or quasi‐random* or quasirandom* or quasi control* or quasicontrol* or quasi* W3 method* or quasi* W3 study or quasi* W3 studies or quasi* W3 trial or quasi* W3 design* or experimental W3 method* or experimental W3 study or experimental W3 studies or experimental W3 trial or experimental W3 design* ) ) |

| S93 | TI pre w7 post or AB pre w7 post |

| S92 | MH "Multiple Time Series" or MH "Time Series" |

| S91 | TI ( (comparative N2 study) or (comparative N2 studies) or evaluation study or evaluation studies ) or AB ( (comparative N2 study) or (comparative N2 studies) or evaluation study or evaluation studies ) |

| S90 | MH Experimental Studies or Community Trials or Community Trials or Pretest‐Posttest Design + or Quasi‐Experimental Studies + Pilot Studies or Policy Studies + Multicenter Studies |

| S89 | TI ( pre‐test* or pretest* or posttest* or post‐test* ) or AB ( pre‐test* or pretest* or posttest* or "post test* ) OR TI ( preimplement*" or pre‐implement* ) or AB ( pre‐implement* or preimplement* ) |

| S88 | TI ( intervention* or multiintervention* or multi‐intervention* or postintervention* or post‐intervention* or preintervention* or pre‐intervention* ) or AB ( intervention* or multiintervention* or multi‐intervention* or postintervention* or post‐intervention* or preintervention* or pre‐intervention* ) |

| S87 | (MH "Quasi‐Experimental Studies") |

| S86 | S80 or S81 or S82 or S83 or S84 or S85 |

| S85 | TI ( "control* N1 clinical" or "control* N1 group*" or "control* N1 trial*" or "control* N1 study" or "control* N1 studies" or "control* N1 design*" or "control* N1 method*" ) or AB ( "control* N1 clinical" or "control* N1 group*" or "control* N1 trial*" or "control* N1 study" or "control* N1 studies" or "control* N1 design*" or "control* N1 method*" ) |

| S84 | TI controlled or AB controlled |

| S83 | TI random* or AB random* |

| S82 | TI ( "clinical study" or "clinical studies" ) or AB ( "clinical study" or "clinical studies" ) |

| S81 | (MM "Clinical Trials+") |

| S80 | TI ( (multicent* n2 design*) or (multicent* n2 study) or (multicent* n2 studies) or (multicent* n2 trial*) ) or AB ( (multicent* n2 design*) or (multicent* n2 study) or (multicent* n2 studies) or (multicent* n2 trial*) ) |

| S79 | S69 or S70 or S73 or S74 or S75 or S76 or S77 or S78 |

| S78 | (MM "Safety") |

| S77 | TI incorrect procedure or AB incorrect procedure |

| S76 | TI ( (patient N2 harm) or (patient N2 threat) ) or AB ( (patient N2 harm) or (patient N2 threat) ) |

| S75 | TI ( (unintention* N2 harm) or (unintend* N2 harm) or (unintention* N2 event) or (unintend* N2 event) ) or AB ( (unintention* N2 harm) or (unintend* N2 harm) or (unintention* N2 event) or (unintend* N2 event) ) |

| S74 | TI ( (clinical error or medical error or surgical error) ) or AB ( (clinical error or medical error or surgical error) ) |

| S73 | S71 and S72 |

| S72 | TI patient or MW patient |

| S71 | (MH "Safety") |

| S70 | TI (error N2 reduc*) or (error N2 prevent*) or (error N2 improv*) or (error N2 lower*) |

| S69 | (MH "Health Care Errors") |

| S68 | S65 or S66 or S67 |

| S67 | AB (safety N4 checklist) or (procedur* N4 checklist) or (preoperat* N4 checklist) or (identity N4 checklist) or (identification N4 checklist) or (verification N4 checklist) or (confirmation N4 checklist) |

| S66 | TI checklist |

| S65 | (MH "Checklists") |

| S64 | S59 or S60 or S61 or S62 or S63 |

| S63 | TI (team* N2 communicat*) or AB (team* N2 communicat*) |

| S62 | (MH "Interprofessional Relations") |

| S61 | (MH "Nurse‐Physician Relations") |

| S60 | (MH "Communication Barriers") |

| S59 | (MM "Communication") |

| S58 | S42 or S43 or S44 or S45 or S46 or S47 or S48 or S49 or S50 or S51 or S52 or S53 or S54 or S55 or S56 or S57 |

| S57 | TI non‐technical skill or AB non‐technical skill |

| S56 | TI ( (team brief* or team meeting) ) or AB ( (team brief* or team meeting) ) |

| S55 | TI ( (aviation or crew resource management or teamstepps) ) or AB ( (aviation or crew resource management or teamstepps) ) |

| S54 | TI wristband or AB wristband |

| S53 | (MH "Radio Frequency Identification") |

| S52 | (MH "Patient Identification") |

| S51 | TI ( (patient N2 identification) or (patient N2 misidentif*) or (patient N2 identity) or (patient N2 verification) or (patient N2 verif*) ) or AB ( (patient N2 identification) or (patient N2 misidentif*) or (patient N2 identity) or (patient N2 verification) or (patient N2 verif*) ) |

| S50 | TI ( (incorrect N3 patient) or (error N3 patient) or (wrong* N3 patient) ) or AB ( (incorrect N3 patient) or (error N3 patient) or (wrong* N3 patient) ) |

| S49 | TI ( (site N2 check*) or (site N2 error) or (site N2 marker) or (site N2 mix‐up) or (site N2 confusion) or (site N2 verif*) ) or AB ( (site N2 check*) or (site N2 error) or (site N2 marker) or (site N2 mix‐up) or (site N2 confusion) or (site N2 verif*) ) |

| S48 | TI situational awareness or AB situational awareness |

| S47 | TI ( (near miss or near misses or never event) ) or AB ( (near miss or near misses or never event) ) |

| S46 | TI (pause or pausing) |

| S45 | TI call‐out or AB call‐out |

| S44 | TI time‐out or AB time‐out |

| S43 | TI skin marking or AB skin marking |

| S42 | TI (wrong N4 surgery) or AB (wrong N4 surgery) |

| S41 | S36 or S37 or S38 or S39 or S40 |

| S40 | TI (preoperative or intraoperative or perioperative) |

| S39 | (MH "Intraoperative Care") |

| S38 | (MH "Perioperative Care") |

| S37 | (MH "Perioperative Nursing") |

| S36 | (MH "Preoperative Care") |

| S35 | S33 or S34 |

| S34 | TI (operating N2 room) or (operating N2 theatre) or (operating N2 theater) |

| S33 | (MH "Operating Rooms") |

| S32 | S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 |

| S31 | TI surgical |

| S30 | TI (surger* or operative procedure) |

| S29 | (MH "Surgery, Operative+") |

| S28 | (MH "Specialties, Surgical+") |

| S27 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 |

| S26 | TI ( (aviation and surg*) ) or AB (aviation N4 surg*) |

| S25 | TI (surg* N2 error) or AB (surg* N2 error) |

| S24 | TI (operating room N2 error) or AB (operating room N2 error) |

| S23 | TI ( (operating room N2 "time‐out?") or (surg* N2 "time‐out?") ) or AB ( (operating room N2 "time‐out?") or (surg* N2 "time‐out?") ) |

| S22 | TI patient marking or AB patient marking |

| S21 | TI ( (preoperativ* N4 marking) or (pre‐operative N4 marking) ) or AB ( (preoperativ* N4 marking) or (pre‐operative N4 marking) ) |

| S20 | TI ( (body N3 marking) or (surgical N3 marking) or (pre‐surg* N3 marking) or (anatomic N3 marking) or (site N3 marking) ) or AB ( (body N3 marking) or (surgical N3 marking) or (pre‐surg* N3 marking) or (anatomic N3 marking) or (site N3 marking) ) |

| S19 | TI ( (wrong N4 surgical procedur*) or (wrong N4 operative procedure) ) or AB ( (wrong N4 surgical procedur*) or (wrong N4 operative procedure) ) |

| S18 | TI ( (surg* N2 checklist) or (surg* N2 check‐list) ) or AB ( (surg* N2 checklist) or (surg* N2 check‐list) ) |

| S17 | TI ( (surg* N4 never event) or (operating room N4 never event) or (operating theatre N4 never event) or (operating theater N4 never event) or (surg* N4 near miss ) or (operating room N4 near miss ) or (operating theatre N4 near miss ) or (operating theater N4 near miss ) or (surg* N4 near misses) or (operating room N4 near misses) or (operating theatre N4 near misses) or (operating theater N4 near misses) ) or AB ( (surg* N4 never event) or (operating room N4 never event) or (operating theatre N4 never event) or (operating theater N4 never event) or (surg* N4 near miss ) or (operating room N4 near miss ) or (operating theatre N4 near miss ) or (operating theater N4 near miss ) or (surg* N4 near misses) or (operating room N4 near misses) or (operating theatre N4 near misses) or (operating theater N4 near misses) ) |

| S16 | TI ( (operating room N4 checklist) or (operating theat* N4 checklist) ) or AB ( (operating room N4 checklist) or (operating theat* N4 checklist) ) |

| S15 | TI ( (surgical procedure N3 verification) or (surgical procedure N3 verify*) or (surgical procedure N3 wrong*) or (surgical procedure N3 confirm*) ) or AB ( (surgical procedure N3 verification) or (surgical procedure N3 verify*) or (surgical procedure N3 wrong*) or (surgical procedure N3 confirm*) ) |

| S14 | TI incorrect surgical site or AB incorrect surgical site |

| S13 | TI ( (surgical site N3 verification) or (surgical site N3 verify*) or (surgical site N3 confirm*) or (surgical site N3 awareness) ) or AB ( (surgical site N3 verification) or (surgical site N3 verify*) or (surgical site N3 confirm*) or (surgical site N3 awareness) ) |

| S12 | TI ( (operating room N3 briefing) or (operating theat* N3 briefing) or (operating room N3 communicat*) or (operating theat* N3 communicat*) or (operating room N3 verif*) or (operating theat* N3 verif*) or (operating room N3 patient confirmation) or (operating theat* N3 patient confirmation) or (operating room N3 confirm* patient) or (operating theat* N3 confirm* patient) or (operating room N3 check identity) or (operating theat* N3 check identity) or (operating room N3 confirm identity) or (operating theat* N3 confirm identity) or (operating room N3 verif* identity) or (operating theat* N3 verif* identity) ) or AB ( (operating room N3 briefing) or (operating theat* N3 briefing) or (operating room N3 communicat*) or (operating theat* N3 communicat*) or (operating room N3 verif*) or (operating theat* N3 verif*) or (operating room N3 patient confirmation) or (operating theat* N3 patient confirmation) or (operating room N3 confirm* patient) or (operating theat* N3 confirm* patient) or (operating room N3 check identity) or (operating theat* N3 check identity) or (operating room N3 confirm identity) or (operating theat* N3 confirm identity) or (operating room N3 verif* identity) or (operating theat* N3 verif* identity) ) |

| S11 | TI ( (pre‐surg* N3 verif*) or (preoperativ* N3 verif*) or (pre‐operativ* N3 verif*) or (preprocedur* N3 verif*) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient confirmation ) or (preoperativ* N3 patient confirmation ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient confirmation ) or (preprocedur* N3 patient confirmation ) or (pre‐surg* N3 confirm* patient ) or (preoperativ* N3 confirm* patient ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 confirm* patient ) or (preprocedur* N3 confirm* patient ) or (pre‐surg* N3 check identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 check identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 check identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 check identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 confirm identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 confirm identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 confirm identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 confirm identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 verif* identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 verif* identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 verif* identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 verif* identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient N2 check*) or (preoperativ* N3 patient N2 check*) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient N2 check*) or (preprocedur* N3 patient N2 check*) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient N2 verif*) or (preoperativ* N3 patient N2 verif*) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient N2 verif*) or (preprocedur* N3 patient N2 verif*) ) or AB ( (pre‐surg* N3 verif*) or (preoperativ* N3 verif*) or (pre‐operativ* N3 verif*) or (preprocedur* N3 verif*) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient confirmation ) or (preoperativ* N3 patient confirmation ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient confirmation ) or (preprocedur* N3 patient confirmation ) or (pre‐surg* N3 confirm* patient ) or (preoperativ* N3 confirm* patient ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 confirm* patient ) or (preprocedur* N3 confirm* patient ) or (pre‐surg* N3 check identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 check identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 check identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 check identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 confirm identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 confirm identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 confirm identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 confirm identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 verif* identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 verif* identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 verif* identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 verif* identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient N2 check*) or (preoperativ* N3 patient N2 check*) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient N2 check*) or (preprocedur* N3 patient N2 check*) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (preoperativ* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (preprocedur* N3 patient N2 identity ) or (pre‐surg* N3 patient N2 verif*) or (preoperativ* N3 patient N2 verif*) or (pre‐operativ* N3 patient N2 verif*) or (preprocedur* N3 patient N2 verif*) ) |

| S10 | TI ( (operating room N3 meeting) or (postoperative N3 meeting) or (post‐operative N3 meeting) or (pre‐surg* N3 meeting) or (preoperative* N3 meeting) or (pre‐operativ* N3 meeting) or (preprocedur* N3 meeting) or (operating room N3 briefing) or (postoperative N3 briefing) or (post‐operative N3 briefing) or (pre‐surg* N3 briefing) or (preoperative* N3 briefing) or (pre‐operativ* N3 briefing) or (preprocedur* N3 briefing) or (operating room N3 pause) or (postoperative N3 pause) or (post‐operative N3 pause) or (pre‐surg* N3 pause) or (preoperative* N3 pause) or (pre‐operativ* N3 pause) or (preprocedur* N3 pause) ) or AB ( (operating room N3 meeting) or (postoperative N3 meeting) or (post‐operative N3 meeting) or (pre‐surg* N3 meeting) or (preoperative* N3 meeting) or (pre‐operativ* N3 meeting) or (preprocedur* N3 meeting) or (operating room N3 briefing) or (postoperative N3 briefing) or (post‐operative N3 briefing) or (pre‐surg* N3 briefing) or (preoperative* N3 briefing) or (pre‐operativ* N3 briefing) or (preprocedur* N3 briefing) or (operating room N3 pause) or (postoperative N3 pause) or (post‐operative N3 pause) or (pre‐surg* N3 pause) or (preoperative* N3 pause) or (pre‐operativ* N3 pause) or (preprocedur* N3 pause) ) |

| S9 | TI ( (surgical N3 debrief*) or (surgery N3 debrief*) or (operating room N3 debrief*) or (operating theater N3 debrief*) or (operating theatre N3 debrief*) ) or AB ( (surgical N3 debrief*) or (surgery N3 debrief*) or (operating room N3 debrief*) or (operating theater N3 debrief*) or (operating theatre N3 debrief*) ) |

| S8 | TI surg* pause or AB surg* pause |

| S7 | TI ( (side N2 check*) or (side N2 marking) or (side N2 maker) or (side N2 information) or (side N2 mix‐up) or (side N2 confusion) ) or AB ( (side N2 check*) or (side N2 marking) or (side N2 maker) or (side N2 information) or (side N2 mix‐up) or (side N2 confusion) ) |

| S6 | TI universal protocol or AB universal protocol |

| S5 | TI ( (wrong operating room or wrong operating theat* or incorrect operating room or incorrect operating theat*) ) or AB ( (wrong operating room or wrong operating theat* or incorrect operating room or incorrect operating theat*) ) |

| S4 | TI ( (wrong site or wrong person or wrong procedure or wrong patient or wrong surgical site) ) or AB ( (wrong site or wrong person or wrong procedure or wrong patient or wrong surgical site) ) |

| S3 | TI ( (wrong side or wrong digit or wrong hip or wrong location or wrong arm or wrong leg or wrong knee or wrong ear or wrong eye or wrong finger or wrong joint or wrong elbow or wrong foot or wrong wrist or wrong disk or wrong disc or wrong level or wrong organ or (wrong N3 amputation)) ) or AB ( (wrong side or wrong digit or wrong hip or wrong location or wrong arm or wrong leg or wrong knee or wrong ear or wrong eye or wrong finger or wrong joint or wrong elbow or wrong foot or wrong wrist or wrong disk or wrong disc or wrong level or wrong organ or (wrong N3 amputation)) ) |

| S2 | TI ( (wrong and surgery) ) or AB wrong surg* |

| S1 | TI wrong site surger* or wrong site surger* |

Appendix 3. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)