Abstract

Objective

To synthesize the literature on associations between social determinants of health and pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity in the US and to highlight opportunities for intervention and future research.

Data Sources

We performed a systematic search using Medline Ovid, CINAHL, Popline, Scopus and ClinicalTrials.gov (1990–2018) using MeSH terms related to maternal mortality, morbidity, and social determinants of health, and limited to the United States.

Methods of Study Selection

Selection criteria included studies examining associations between social determinants and adverse maternal outcomes including pregnancy-related death, severe maternal morbidity, and emergency hospitalizations or readmissions. Using Covidence, three authors screened abstracts and two screened full articles for inclusion.

Tabulation, Integration, and Results

Two authors extracted data from each article and the data were analyzed using a descriptive approach. A total of 83 studies met inclusion criteria and were analyzed. Seventy eight out of 83 studies examined socioeconomic position or individual factors as predictors, demonstrating evidence of associations between minority race and ethnicity (58/67 studies with positive findings), public or no insurance coverage (21/30), and lower education levels (8/12) and increased incidence of maternal death and severe maternal morbidity. Only 2/83 studies investigated associations between these outcomes and socioeconomic, political and cultural context (e.g. public policy); and 20/83 studies investigated material and physical circumstances (e.g. neighborhood environment, segregation), limiting the diversity of social determinants of health studied as well as evaluation of such evidence.

Conclusion

Empirical studies provide evidence for the role of race and ethnicity, insurance, and education in pregnancy-related mortality and severe maternal morbidity risk, although many other important social determinants, including mechanisms of effect, remain to be studied in greater depth.

Précis

Studies demonstrate the role of race, ethnicity, insurance, and education in pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity risk but lack inclusion of mechanisms and other social determinants.

INTRODUCTION

Mitigation of adverse maternal health outcomes is an urgent public health issue in the United States (US). The rate of maternal mortality has been steadily increasing in the US within the past 30 years and is one of the highest among high-income countries [1–3]. For example, the US maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in 2017 was 19 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, compared to 10 in Canada and 7 in the United Kingdom [3]. The US has experienced a parallel increase in maternal morbidity, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) Maternal Morbidity Working Group as “any health condition attributed to and/or aggravated by pregnancy and childbirth that has a negative impact on the woman’s well-being” [4,5]. Maternal morbidity includes “near-miss” events in which women nearly die during pregnancy or childbirth, as well as less life-threatening conditions that may significantly impact quality of life or future health outcomes [5].

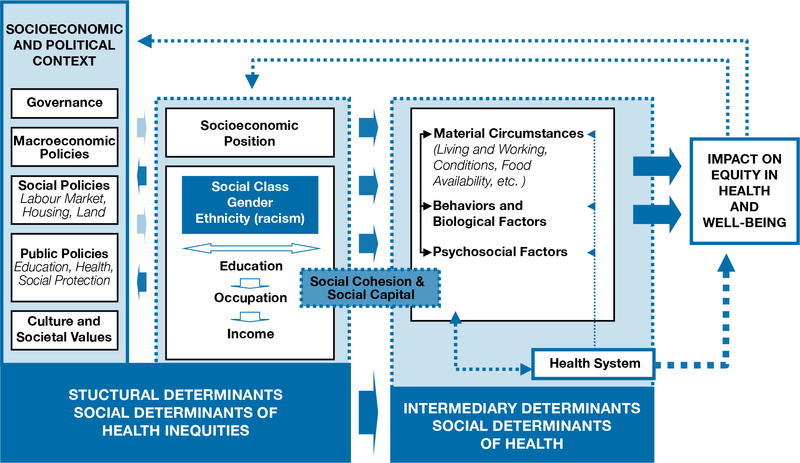

Increases in obesity and chronic disease prevalence, delayed childbearing, and cesarean delivery rates are all thought to contribute to an increase in maternal mortality and morbidity [6]. However, social determinants of health shape the risk of these more proximal factors and thus are also substantial drivers of maternal mortality and morbidity (see Figure 1, from the WHO conceptual framework on social determinants of health) [7]. According to the definition from the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), built off the work of epidemiologists Michael Marmot and Richard Wilkinson, social determinants of health consist of the material and social environmental conditions in which people are born, live, work, and age that may affect the health of an individual [8,9]. Social and political institutions and processes generate stratification and social class division within a society. Key proxy indicators of such structural stratifiers are what constitute “socioeconomic position” and include income, education, occupation, race and ethnicity, and gender. Individuals in these positions, through differential exposure and vulnerability to intermediary social determinants of health (material circumstances, biological or behavioral factors, psychosocial circumstances, quality of and access to health care) may experience differential rates of pregnancy complications, death, and disability [8].

Figure 1:

Conceptual framework of the social determinants of health. Reprinted from A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization 2010. Available at https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf

A robust global health literature incorporates social determinants of health into models explaining maternal mortality in low and middle-income countries, where the vast burden of maternal deaths occur [10–12]. These are aided by maternal death audits and social autopsies, which are questions designed to identify the social, behavioral and health system factors that may have contributed to deaths [13]. Further, many studies have reviewed the role of social determinants of health in explaining disparities in neonatal or birth outcomes including preterm birth, low-birth-weight and neonatal mortality, both globally and in the US [14]. However, relatively little attention has been given to examining social determinants of health and maternal health outcomes in the US, despite worsening trends and the urgent need to intervene [15].

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the current literature on the impact of social determinants on pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity in the US and, using the WHO Conceptual Framework on the Social Determinants of Health, identify potential areas for research, public health interventions, and clinical opportunities to reduce disparities.

SOURCES

We registered the review protocol with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42018102415. Details are available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018102415.

We designed this systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. We identified studies by searching Medline Ovid, CINAHL, Popline, Scopus and ClinicalTrials.gov on July 8th, 2018 for articles published in English between 1990 and 2018. The search strategy, created in conjunction with a librarian, consisted of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and text words relating to pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity and social determinants of health, with the goal to include as many relevant papers as possible (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). We limited our search to studies done in the US.

STUDY SELECTION

We used the following inclusion criteria (see Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx) to determine eligible studies: 1) quantitative, empirical study; 2) published in English; 3) population was pregnant women who delivered in the US; 4) outcomes focused on measures of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity; 5) included exposures related to social determinants of health; and 6) examined the relationship between social determinants of health and pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity. We excluded studies that focused only on neonatal or birth outcomes (e.g. low birth weight, preterm birth) as well as those that did not include social determinants of health as a primary independent variable or whose primary exposure or outcome was an intermediary behavior (e.g. time of entry to prenatal care).

Two researchers independently screened all titles and abstracts for inclusion and exclusion criteria using the online software Covidence. A third researcher resolved conflicts. Two researchers independently reviewed the full texts of all eligible abstracts, again with a tie-breaking third review when necessary. We also reviewed relevant studies published past the July 8th, 2018 search date or found from reference lists of included articles.

One researcher assessed study quality using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies or for Case-Control studies, which is a series of guiding questions to appraise individual study quality and risk of bias. A “good” study has the least risk of bias, a “fair” study is susceptible to some bias but deemed not sufficient to invalidate its results and a “poor” rating indicates significant risk of bias [16]. A detailed list of these questions can be found in Appendix 3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx. Studies rated as poor were excluded from the review. Data were extracted from included studies and encompassed study design, sample size and data sources, exposure and outcome variables, covariates and key findings, including odds ratios (OR) or risk ratios (RR), confidence intervals (CI) and p-values where applicable. Given the diversity of study designs and variables studied and controlled for, we decided that a descriptive synthesis of the results was appropriate.

Given the large number of studies, we synthesized our results by outcomes and by type of social determinants of health studied. The former included: 1) pregnancy-related death, 2) severe maternal morbidity, 3) emergency hospitalizations or readmissions and 4) non-severe direct maternal morbidity (DMM). We defined pregnancy-related death according to the CDC’s definition of “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of a pregnancy—regardless of the outcome, duration or site of the pregnancy—from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes” [2]. We chose to exclude pregnancy-associated deaths such as homicide or suicide to narrow our scope and to keep outcome definitions consistent. We defined severe maternal morbidity based on a series of obstetric outcomes used by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [1]. The third category included studies with measures of pregnancy-related hospitalizations (excluding delivery), emergency room encounters and readmissions because these represent proxies of maternal morbidity [1,17]. We categorized ICU admissions as a part of severe maternal morbidity as this has been the convention in prior literature [17]. “Non-severe,” “direct” maternal morbidity describes less-severe cases of maternal ill health not captured by the WHO or CDC definition of maternal near-miss or severe maternal morbidity and is defined by the framework in Chou et al. (2016) [4]. However, we ultimately excluded studies in this fourth category because there is existing literature synthesizing evidence for specific direct morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, etc., and we chose to focus on the most severe maternal events. Specific conditions included under these definitions are listed in Appendix 2 (http://links.lww.com/xxx).

We further organized our findings into three categories of social determinants of health using a framework adapted from WHO’s conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health [8]: 1) socioeconomic, political and cultural context, 2) socioeconomic position and 3) material and physical circumstances. The first category includes broader issues like economic and social policies. Socioeconomic position includes individual characteristics such as race or ethnicity, education, occupation, income and psychosocial factors. Material and physical circumstances include environmental conditions and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES), segregation, crime, and access to and quality of health care (see Appendix 2 [http://links.lww.com/xxx]).

RESULTS

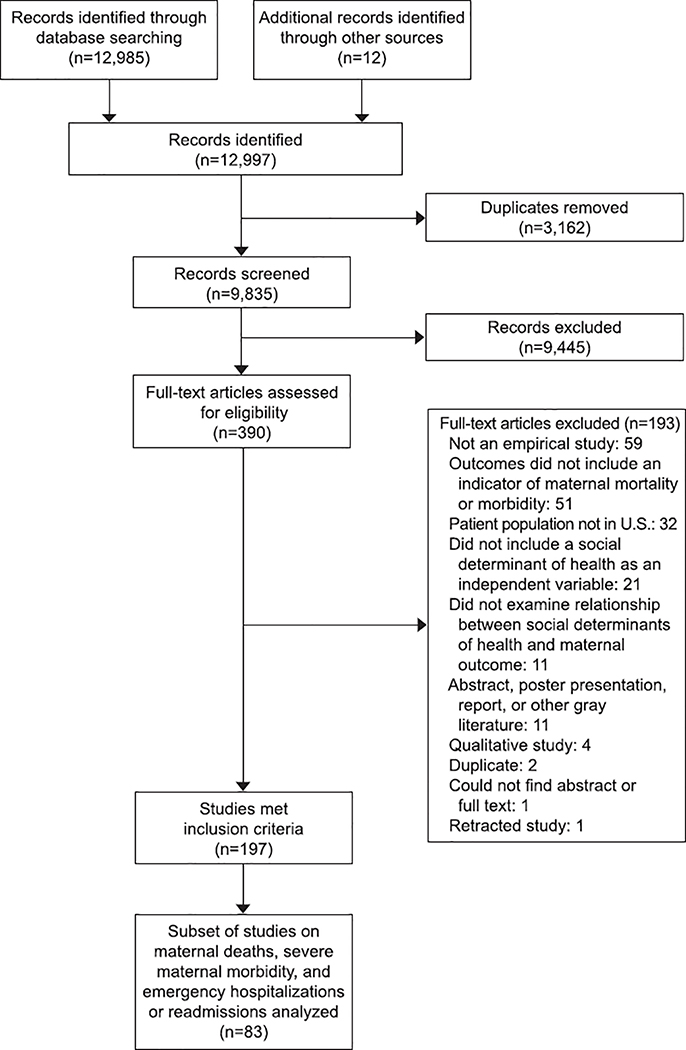

A total of 9835 records were identified and screened (Figure 2). During the screening process, there were 9473 agreements for inclusion and 362 conflicts resolved by a third researcher, for a percent agreement of 96.3%. The selection process yielded a final number of 199 studies, of which 83 were included in our results based on the three outcome categories analyzed (see Methods section).

Figure 2:

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1 lists the frequency by which each predictor and outcome was studied in the literature. Of note, the majority of studies examined “socioeconomic position and individual factors” as predictors, most of which focused on race or ethnicity (67/83 studies) and insurance (30/83). Much fewer studied “material and physical circumstances” (20 studies) and “socioeconomic, political and cultural context” (2 studies on state policy). Tables 2, 3 and 4 are summary tables that report the volume of studies demonstrating an association for specific social determinants of health and outcomes, as well as the direction of those associations. Appendix 4, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx, summarizes additional details on study design, sample size and data sources, exposure and outcome variables, covariates, key findings including magnitude of associations (ORs, RRs and CIs), and quality ratings. Data sources included nationwide or multistate (30 studies), state-level (29), city-level (5), or hospital-level (3) administrative data; medical records (14) and surveys/questionnaires (2). All studies were rated as Good or Fair by the NIH Study Quality Assessment Tool, and thus none were excluded from the analyses (see Appendix 3 [http://links.lww.com/xxx] for individual assessments of quality).

Table 1:

Predictors and Outcomes by Volume of Studies

| Predictors | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal death |

SMM | Emergency hospitalizations- readmissions |

# of studies examining each predictor |

|

|

Socioeconomic, Political and Cultural Context 2 studies | ||||

| State policy* | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

|

Socioeconomic Position and Individual Factors 78 studies | ||||

| Maternal race or ethnicity | 29 | 42 | 5 | 67 |

| Insurance or payer | 10 | 20 | 5 | 30 |

| Maternal education | 6 | 8 | 0 | 13 |

| Maternal residence† | 4 | 6 | 1 | 11 |

| Marital status | 6 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

| Nativity, country of origin | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| Maternal employment status | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Physical violence or abuse during pregnancy | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Individual household income | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

Material and Physical Circumstances 20 studies | ||||

| Area-level characteristics‡ | 5 | 8 | 3 | 15 |

| Hospital characteristics§ | 2 | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| # of studies examining each outcome | 36 | 52 | 9 | 83 |

Includes state Medicaid payment policy and coverage of medically necessary abortion

Includes location rurality and region

Includes median household income, poverty level, % employment rate, % urban and % minority by zip code, census tract or state

Includes whether the hospital was minority-serving, and urban vs. rural location

Table 2.

Summary of Social Determinants and Maternal Outcome Associations by Volume of Studies: Socioeconomic, Political and Cultural Context

| ↑ = increased risk or positive association, ↓ = decreased risk or negative association, — = no association or not significant “Positive finding” indicates the number of studies showing significant associations in the same direction | |||

| SDH | Mortality | SMM | Emergency Hospitalization or Readmission |

| State policy |

Overall composite SMM ↓ With State Medicaid coverage of medically necessary abortion[18] — For Medicaid blended payment compared to previous payment[19] |

||

Table 3.

Summary of Social Determinants and Maternal Outcome Associations by Volume of Studies: Socioeconomic Position and Individual Factors

| ↑ = increased risk or positive association, ↓ = decreased risk or negative association, — = no association or not significant “Positive finding” indicates the number of studies showing significant associations in the same direction | |||

| Race and Ethnicity (58/67 positive findings for minority groups compared to non-Hispanic White) | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference, except otherwise stated |

Reference, except otherwise stated ↑ Anesthetic complications, compared to black women[65] |

|

| Non-Hispanic Black (53/60 positive findings) |

Cause-specific deaths ↑ Ectopic pregnancy[21,42] ↑ Abortion[22] ↑ Cardiovascular causes[30] ↑ Preeclampsia, eclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension[36,39] ↑ Hemorrhage[39] ↑ Case-fatality rates for preeclampsia, eclampsia, placental abruption, placenta previa and postpartum hemorrhage[43] — Mortality after pregnancy-related intracerebral hemorrhage[23] In-hospital mortality ↑ [24–27,29,32,41] ↑ At white-serving but not black- or Hispanic-serving hospitals[27] — [69] Pregnancy-related mortality ↑ [28,31,33–35,37–40] Failure-to-rescue ↑ [44] Preventability of maternal death —[45] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [26,27,29,41,44,49–51,53,54,56,58] ↑ Particularly among cesarean deliveries[60,61] ↑ Among women with cardiomyopathy in a non-teaching hospital[52] ↓ Among those with inpatient ectopic pregnancies[55] — Mothers with HIV, black vs non-black[124] — Among those with pre-viable premature rupture of membranes, black vs. non-black[125] Individual outcomes ↑ Severe sepsis[67,71] ↑ Intracerebral hemorrhage[23] ↑ Postpartum hemorrhage[126–128] ↑ Severe preeclampsia or eclampsia[49,72,129–131] — Severe preeclampsia[132] — Eclampsia[76] ↑ Peripartum transfusion[49,74,133,134] ↑ Stroke [73] ↑ Intracranial venous thrombosis, among Medicaid patients[135] ↑ Acute renal failure[49,133] ↑ Heart failure, mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome[49] ↑ Hysterectomy in low-risk patients[84] ↓ Uterine rupture[66] |

↑ Postpartum readmission[61,62] ↑ ED visit within 90 days of delivery[64] ↑ Pregnancy-associated hospitalization[63] ↑ Ectopic pregnancy hospitalization >4 days[55] |

| Hispanic (24/30 positive findings) |

Pregnancy-related mortality ↑ [28,46] — [33,39,47] ↓ [34,35] In-hospital mortality ↑ [26,29] — [41] Among women with preeclampsia or eclampsia Cause-specific deaths ↑ Intracerebral hemorrhage[23,39,46] ↑ Pregnancy-induced hypertension[39,46] ↑ Hemorrhage[46] ↑ Mortality after pregnancy-related intracerebral hemorrhage[23] — Hemorrhage[39] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [26,29,50,51,53,57–60] ↑ Among women with cardiomyopathy in a non-teaching hospital[52] — Among those with inpatient ectopic pregnancies[55] Individual outcomes ↑ Blood transfusion[49,133] ↑ Hysterectomy[49]; in low-risk patients[84] ↑ Acute renal failure [133] ↑ Severe sepsis[67,71] ↑ Postpartum hemorrhage[126–128] ↑ Eclampsia[72] — Intracranial venous thrombosis, among Medicaid patients [135] |

↑ Ectopic pregnancy hospitalization >4 days[55] |

| Asian-Pacific Islander (14/16 positive findings) |

In-hospital mortality ↑ [48] — [26] Cause-specific deaths — Mortality after pregnancy-related intracerebral hemorrhage[23] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [26,48,50,51,53,56] ↑ Among women with cardiomyopathy in a non-teaching hospital[52] — Among those with inpatient ectopic pregnancies[55] Individual outcomes ↑ Severe sepsis[67,71] ↑ Postpartum hemorrhage[126,128] ↑ Peripartum transfusion[49,74] ↑ Eclampsia[72] ↑ Hysterectomy[49] |

— Ectopic pregnancy hospitalization >4 days [55] |

| Native American and American Indian (4/4 positive findings) |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [26,50] Individual outcomes ↑ Transfusion and hysterectomy[49] ↑ Eclampsia[136] |

||

| Insurance (21/30 positive findings for public or no insurance coverage compared to private insurance) | |||

| Private insurance (2/3 positive findings) | Reference, unless otherwise stated |

Reference, unless otherwise stated Overall composite SMM ↓ Compared to Medicaid[26] — Among mothers with pre-viable PROM, as compared to non-private insurance or no insurance [125] Individual outcomes ↓ Hysterectomy, compared to Medicare[84] |

|

| No private insurance (no insurance + public insurance combined variable) |

Individual outcomes ↑ Severe sepsis[71] |

||

| No insurance or self-pay (9/12 positive findings) |

Cause-specific deaths ↑ Severe sepsis[67] ↑ Acute respiratory distress syndrome[68] In-hospital mortality ↑ [25,44,45,68] — [69] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [44,53,60] — With blood transfusion, ↑ without blood transfusion [56] Individual Outcomes ↑ Severe sepsis[67] — Anesthesia-complications[65] — Hysterectomy, compared to Medicare [84] |

↑ Pregnancy-associated hospitalizations[63] |

| Public insurance (14/24 positive findings) |

Cause-specific deaths ↑ Cardiovascular death[30] In-hospital mortality ↑ [44,45] — [29,69,70] — by State Medicaid coverage of medically necessary abortion[18] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [44,50,53,60]; Compared to non-Medicaid[58] ↑ Among women with cardiomyopathy [52] — [61] — [56] ↓ For Medicaid managed care vs. private managed care[70] Individual outcomes ↑ Eclampsia[72] — Ectopic-pregnancy related[55,75] — Peri- and post-partum stroke[73] — Anesthesia-complications[65] — Peripartum transfusion[74] — Hysterectomy, compared to Medicare[84] |

↑ Pregnancy-associated hospitalizations[63] ↑ Postpartum readmission[62] ↑ ED visit within 90 days of delivery[64] ↑ Ectopic pregnancy hospitalization >4 days[55] >2 days[75] |

| Type of insurance |

Overall composite SMM — For Medicaid managed care vs. fee-for-service[70] Individual outcomes ↑ Preeclampsia, for Medicaid managed care vs. fee-for-service[70] |

||

| Maternal Education | |||

| High school education or more (1/2 positive finding) | Reference unless otherwise stated |

Reference unless otherwise stated Overall composite SMM ↓ Some post-graduate as compared to high school[53]; college graduate or higher as compared to high school graduate only for cesarean deliveries[60] — Some college as compared to high school[53]; college graduate or higher as compared to high school graduate only for vaginal deliveries[60] |

|

| Less than high school education (8/12 positive findings) |

Pregnancy-related mortality ↑ [28,33] ↑ Impact higher on black women than white women[28] — [47] ↑ But dropped out of regression model after adjustment[31] Maternal mortality (within 42 days) ↑ Rates, unadjusted [33] In-hospital mortality — [25,29] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ Compared to high school graduate only, both vaginal and cesarean deliveries[60] ↑ <8 years of education compared to >12 years of education, for vaginal deliveries[61] — <8 years of education compared to >12 years of education, for cesarean deliveries [61] — [29,58] Individual Outcomes ↑ Sepsis[71] ↑ Eclampsia[72,76] |

|

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | Reference, unless otherwise stated | Reference, unless otherwise stated | |

| Unmarried (5/10 positive findings) |

Pregnancy-related mortality ↑ [33,39] ↑ among white women but not black women[28] — [47,69] In-hospital mortality — [29] |

Overall composite SMM — [29,58] — ICU admission[54] ↑ [60] Individual Outcomes ↑ Missing compared to no missing paternal information; risk of eclampsia[77] |

|

| Residence | |||

| Region of residence (5/6 positive findings) |

Maternal mortality (within 42 days) ↑ in South vs other parts of US[33] — In boroughs in NYC vs. Bronx[47] Pregnancy-related mortality (within 1 year) ↑ in Mississippi Delta vs. non-Delta regions[78] ↑ in Chicago city vs. suburbs and remainder of Illinois[39] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ in Northeastern, Northern, Southeastern, Southern vs Western part of Wisconsin[50] ↑ in all parts of Maryland vs Baltimore metro[56] |

|

| Rurality (urban vs. non-urban) (3/5 positive findings) |

Overall composite SMM ↑ For non-urban versus urban residence[58] — [61] — Among low-risk women planning midwife-led community birth[85] Individual outcomes ↑ Anesthesia-complications[65] |

↑ Patients from more urban zip codes experienced longer hospitalizations related to ectopic-pregnancy than others.[75] | |

| Nativity or country of origin | |||

| US-Born | Reference | ||

| Foreign-Born (3/6 positive findings) |

In-hospital mortality — [25] Pregnancy-related mortality — [47] ↑ Foreign-Born Hispanic vs. US-born Hispanic [46] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ Foreign-Born Hispanic vs. US-born Hispanic [59,79] —[60] |

|

| Maternal employment status | |||

| Employed | Reference | Reference | |

| Unemployed (1/2 positive findings) |

In-hospital mortality — [25] |

Overall composite SMM — [57]; For vaginal deliveries [60] ↑ For cesarean deliveries[60] |

|

| Other | |||

| Physical violence or abuse during pregnancy (3/3 positive findings) |

Individual outcomes ↑ Uterine rupture, transfusion, hemorrhage, infection[80] |

↑ Pregnancy-associated hospitalization[81,82] ↑ Postpartum readmission[80] |

|

| Individual household income(1/1 positive finding) |

Individual outcomes — Comparing first (<$32,669) and third tertile (>$44,485) of annual household income vs second tertile ($32,669–44,485) for eclampsia[76] |

||

Table 4.

Summary of Social Determinants and Maternal Outcome Associations by Volume of Studies: Material and Physical Circumstances

| ↑ = increased risk or positive association, ↓ = decreased risk or negative association, — = no association or not significant “Positive finding” indicates the number of studies showing significant associations in the same direction | |||

| Area-Level Characteristics | |||

| Low-income neighborhoods by zip code (5/8 positive findings) |

Pregnancy-related mortality ↑ [31]; ↑ For white women[28] — For black women[28] In-hospital mortality — Cases vs. controls[69] |

Individual outcomes — For ectopic pregnancy outcomes[55] — Peri- and post-partum stroke[73] Overall composite SMM ↑ Unadjusted, — adjusted: for median household incomes <$81,874 compared to >$123,856[56] |

↑ ED visit within 90 days of delivery[64] ↑ Postpartum readmission[62] |

| High-income neighborhoods by zip code (3/3 positive findings) | Reference, unless otherwise stated |

Overall composite SMM ↓ Compared to lowest quartile of income[26,44] Individual outcomes ↓ Hysterectomy, highest quartile compared to lowest quartile[84] |

|

| % unemployment (1/1 positive finding) | ↑ By zip code: ectopic-pregnancy hospitalization longer than 2 days[75] | ||

| % of female-headed households (1/1 positive finding) | By zip code: ↑ >12% vs. <6.1%, Unadjusted[56] | ||

| % of women without high school diploma (2/3 positive findings) |

Maternal mortality ratio By state MMR ranking: ↑ [83], — [38] |

By zip code: ↑ >6.2 vs. <1.8%, Unadjusted[56] | |

| % women uninsured (1/2 positive findings) |

Maternal mortality ratio By state MMR ranking: —% Deliveries paid by governmental insurance [38] —% Women with health care coverage [38] |

By zip code: ↑ >7.4% vs <2.2% Unadjusted[56] | |

| % people living below poverty line (2/3 positive findings) |

Maternal mortality ratio By state MMR ranking: — [38] |

By zip code: ↑ Severe sepsis[67] ↑ >9.2% vs. <2.9% Unadjusted[56] |

|

| % race (3/4 positive findings) |

Maternal mortality ratio By state MMR ranking: ↑ % Deliveries to African American women [38,83] —% Deliveries to Hispanic, Native American, Asian women [38] |

↑ Patients from more African American zip codes experienced longer hospitalizations related to ectopic-pregnancy than others[75] | |

| % unmarried mothers (1/1 positive finding) |

Maternal mortality ratio By state MMR ranking: ↑ [38] |

||

| % rural population (0/1 positive finding) |

Maternal mortality ratio By state MMR ranking: — [38] |

||

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Minority-serving or % of minority deliveries compared to white-serving or % white deliveries (5/5 positive findings) |

In-hospital mortality ↑ [27] |

Overall composite SMM ↑ [27,56,59,87] |

|

| Hospital teaching status, ownership, nursery level and volume of deliveries; risk-standardized severe maternal morbidity rates (1/1 positive finding) |

Overall composite SMM ↓ Teaching status, Level 3/4 nursery, private ownership, and very high-volume status; but did not fully account for excess risk among black women[88] |

||

| Public vs. Private (reference) (1/1 positive finding) |

In-hospital mortality ↑ for Hispanic-serving hospitals[27] |

||

| Rural vs. Urban (reference) (2/4 positive findings) |

In-hospital mortality — [86] |

Individual outcomes — For ectopic pregnancy outcomes[55] |

↑ Postpartum readmission for women delivering in a rural vs. urban hospital[62] ↑ For ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations >4 days[55] |

| % of Medicaid-insured or uninsured (1/1 positive finding) | ↑ [56] | ||

Social context is the social and political mechanisms that generate hierarchies and stratification of populations within a society, including policies and macroeconomic factors [8]. Only two studies addressed such contextual factors, both of which focused on state Medicaid coverage of reproductive and childbirth care (Table 2). These studies reported a decreased risk of severe maternal morbidity but not in-hospital mortality associated with coverage of medically necessary abortion [18],and no association between severe maternal morbidity and delivery reimbursement [19]. There were no studies examining the influence of politics, macroeconomic factors or social policies on maternal outcomes.

Socioeconomic position (SEP) is the result of social and economic factors that stratify individuals or groups within hierarchies of power [8,20]. Indicators of SEP, including race or ethnicity, insurance, and education, were the most commonly studied social determinants of health in our review (Table 3).

The majority of studies (67/83) on maternal death or severe morbidity studied race or ethnicity as a predictor; of those, 58/67 studies found associations with minority race or ethnicity and higher risk of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity. Among black women, national and state-level studies consistently found higher pregnancy-related mortality risks, even when controlling for factors such as insurance coverage, marital status and medical conditions [21–43]. Moreover, studies reported increased case-fatality [43], failure-to-rescue (death in the setting of severe morbidity) [44], and preventable maternal deaths among black women [45], suggesting that management of severe morbidity may play a role in death disparities. Subgroup analyses found higher risks of pregnancy-related mortality among black women in the lowest risk tertile [31], delivered normal- versus low-birth-weight infants [40], or had a low-to-moderate parity [40]. The racial disparity was most pronounced for deaths due to cardiomyopathy, hemorrhage, respiratory and anesthesia-related complications [31].

Prior to 2006, crude maternal mortality rates or risk have been found to be higher among Hispanic women compared to white women, but lower compared to black women [28,33,39,46,47]. More recently (2008–2014), the unadjusted MMR for Hispanic women fell below the MMR for non-Hispanic white women, largely due to an increase in mortality among non-Hispanic white women [34,35]. However, multivariate studies continue to demonstrate that Hispanic ethnicity increases risk of adjusted in-hospital mortality and cause-specific deaths [23,26,29,39,46]. No study in our review evaluated maternal deaths among American Indian women. Two nationwide retrospective cohort studies found higher rates of in-hospital mortality for Asian-Pacific Islander (API) women, although in one study this was not significant due to wide confidence intervals [26,48].

Similarly, minority women across the US were more likely to experience severe maternal morbidity than white women. Depending on the study, black women had adjusted risk ratios ranging from 1.2 to 5 [26,27,29,41,44,49–56]; Hispanic women 1.3 to 3.4 [26,29,50–53,57–60]; API women 1.2 to 1.6 [26,48,50–53,56]; and American Indian women 1.3 to 1.8 [26,50] times higher of experiencing any form of severe maternal morbidity compared with white women. Table 3 lists the studies demonstrating associations with specific severe maternal morbidity outcomes (sepsis, intracerebral hemorrhage, eclampsia, etc.) and among specific populations. In almost all instances, racial and ethnic minority women experienced larger increases in severe maternal morbidity when multiple chronic conditions were identified, suggesting increased case morbidity [27,49]. Moreover, black women had higher rates of readmission [61,62], pregnancy-associated hospitalizations [63], an emergency department (ED) visit within 90 days of delivery [64], or longer-than-anticipated ectopic pregnancy hospitalizations [55].

Of note, only two studies found decreased risk of severe maternal morbidity among minority women, one for anesthesia-related complications [65] and another for uterine rupture [66].

Thirty out of 83 studies examined insurance coverage as a predictor; out of those, 21 found an association with public (Medicaid) or no insurance coverage and higher risk of maternal death or severe maternal morbidity compared to private insurance. More specifically, studies have found associations between lack of insurance and higher risk of cardiovascular, respiratory, and severe sepsis-related death and in-hospital mortality [25,30,44,45,45,67,68], although the significance of the association was not consistent [18,29,69,70].

Women with Medicaid or no insurance had higher risk of severe maternal morbidity compared to those with private insurance in several [44,50,53,58,60,67,71,72] but not all [55,56,61,65,73–75] studies (Table 3). One study found Medicaid managed care group had similar maternal outcomes compared to Medicaid fee-for-service group, and slightly lower maternal adverse outcomes but increased likelihood of preeclampsia compared to private managed care [70]. Women who were self-pay or had public compared to commercial insurance plans, regardless of race or ethnicity, had higher risks of hospitalization [63], readmission [62], an ED visit within 90 days of delivery [64], or a longer ectopic-pregnancy hospitalization [55,75].

eight out of 12 studies found that lower education levels were associated with increased risk of maternal death and severe morbidity. Nationwide cross-sectional studies have consistently found that women who have more education have lower pregnancy-related mortality ratios and rates [28,33]. However, at all levels of education, mortality was still higher for black than white women and the impact of education on mortality was larger for non-blacks than blacks [28].

Level of education was inversely associated with severe maternal morbidity in multiple studies [53,71,72,76], though the significance of results was impacted by sample size and level of adjustment [29,58]. The magnitude and significance of findings may vary by method of delivery, with higher education protective for women undergoing vaginal but not cesarean deliveries [60,61].

Only 10 studies examined marital status as a predictor of maternal death and severe morbidity, with 5 demonstrating significant findings. Pregnancy-related mortality ratios have been found to be higher among unmarried women than married women in state and national analyses [33,39] although this association was not found in smaller city- and hospital-level studies [29,47,69]. Patterns differed by race, with higher mortality ratios among white unmarried versus married women but lower ratios or no difference comparing black married to unmarried women [28].

Being unmarried as compared to married either slightly increased the odds of [60] or was not significantly associated with severe maternal morbidity [29,54,58]. Missing paternal information was found to be associated with a higher risk of eclampsia among twin pregnancies in a retrospective cohort [77].

Few studies examined employment status (3 studies), nativity (6) or other individual-level predictors (4) in association with pregnancy-related mortality or severe maternal morbidity. Foreign-born Hispanic women had a higher risk of pregnancy-related mortality compared to US-born Hispanic women [46]. Two other studies found no association between mortality and employment status or nativity [25,47]. Women living in the South versus other parts of the US [33], and in the Mississippi Delta region versus non-Delta region [78] had higher rates of mortality.

Foreign-born Hispanic women in New York City and California had higher odds of severe maternal morbidity compared to US-born Hispanic women, including eclampsia and preeclampsia [59,79]. We did not find convincing evidence of associations between unemployment or household income and severe maternal morbidity [60,76].

Women who experienced assault during pregnancy had increased odds of placental abruption, blood transfusion, hysterectomy, hemorrhage, and uterine rupture [80]. Finally, women who reported physical violence or intimate partner violence during pregnancy had 1.3–1.6 higher risk of antepartum hospitalization and 3 times risk of readmission within 90 days postpartum [80–82].

Only 20 studies examined what was categorized as material and physical circumstances, including area-level or hospital characteristics (Table 4). For neighborhood-level characteristics, three studies examined neighborhood SES, using median household income by zip code proxy, as a predictor of maternal mortality. Two large studies in New York City and California found increased pregnancy-related mortality in lower-income versus higher-income communities [28,31], although this difference was not significant in a smaller, single-hospital sample [69].

Studies examining state-level characteristics reflected results found in individual predictor studies. State MMR or mortality ranking is positively associated with the state percentage of unmarried mothers [38], percentage of women not having completed high school [83], and proportion of non-Hispanic black women [38,83]. However, one study found no association with percentage of maternal education less than high school, deliveries paid by government insurance, women with health care coverage, proportion of non-black minority women, poverty or rural population [38].

Low neighborhood SES (low median household income or percentage of people living under the poverty line by zip code) has been found to be associated with higher risk or odds of severe maternal morbidity,[44,56,67,84] but not for certain outcomes like inpatient ectopic pregnancy outcomes [55] or peri- and postpartum stroke [73]. Those from lower income zip-codes were also more likely to have an ED visit within 90 days of delivery [64] or postpartum readmission [62].

Women in New York State and Tennessee’s Medicaid program from non-urban versus urban residences had a higher risk complications from anesthesia [61,65]. Among a sample of low-risk women who planned midwife-led community births, however, rurality did not increase the risk of serious complications [85]. Other applicable community-level factors such as percent of female-headed households, women without a high school diploma, and uninsured women were found in one study to have a negative association with risk of severe maternal morbidity, although estimates were not adjusted for potentially confounding variables [56].

With regards to hospital characteristics, two studies found that delivering at a majority black-serving versus white or Hispanic-serving hospital, and public versus private Hispanic-serving hospital, were associated with a higher risk of in-hospital mortality [27]. Another California study found no evidence of association between rural versus urban hospital location and incidence of maternal mortality [86].

Women who delivered in majority black-serving or Hispanic-serving hospitals (>50% or hospitals with highest quartile of proportions of minorities) had higher severe maternal morbidity rates than those in non-majority or low black-serving hospitals or Hispanic-serving hospitals [27,59,87]. Likewise, higher percentages of black deliveries within a hospital were associated with an increase in severe maternal morbidity rates [56]. In New York City, black women were more likely to deliver in a hospital with higher risk-adjusted severe maternal morbidity rates than white women. Hospital teaching status, level 3/4 nursery, private ownership, and very high delivery volume were associated with lower severe maternal morbidity rates, but did not fully account for the excess risk among black women [88]. The hospital percentage of Medicaid-insured and uninsured deliveries was also associated with a higher severe maternal morbidity rate [56]. Women delivering in a rural hospital had higher risk of readmission [62] and longer hospitalization stay [55] than those delivering in urban hospitals.

DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to synthesize the current literature examining the relationship between social determinants of health and pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity. A large number of studies studied individual-level indicators of SEP in relation to maternal outcomes; of those, the majority suggest that black race and Hispanic ethnicity, lack of insurance, and lower education are significantly associated with higher risk of maternal mortality and morbidity. The considerably fewer studies examining the role of marital status, employment and income in maternal outcomes reported either a non-significant or small association with mortality or severe maternal morbidity. Literature analyzing effects of the socioeconomic and political context or area-level physical and material circumstances on maternal outcomes was even sparser. In the following discussion, we identify gaps in the literature which future research should address, challenges for research and policy intervention, and clinical implications.

Race and ethnicity, insurance, or maternal education comprised the majority of social determinants of health studied in this systematic review, all of which are proxies for socioeconomic position. Fewer studies investigated the role of socioeconomic and political context or area-level physical and material circumstances in influencing maternal outcomes. Determinants such as food insecurity, crime, housing insecurity, and social policy, among others may contribute directly or indirectly to maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity, but have not been explicitly studied [89]. State-level or even international comparisons may be necessary to elucidate macro-level determinants.

In addition to the lack of breadth of social determinants of health, a significant limitation of this literature is how studies conceptualized or measured these variables, particularly for constructs like race. Often studies analyzing administrative databases or medical charts used observed or self-identified race or ethnicity as an aggregate variable. The former may not be accurate, and the latter may fail to account for differences within racial groups or for racial ambiguity. For example, few studies in this review subdivide their racial and ethnic analyses by country of origin or maternal education—factors which may more adequately describe their social position and in turn impact mortality and severe maternal morbidity. Moreover, as other scholars have noted, race is not an isolated risk factor but rather a marker of risk for racism-related exposures, shaped by socio-historical context [90]. We did not find any studies in this review that explicitly studied measures of individual and structural racism (e.g. perceived everyday racism and residential segregation) in association with severe maternal morbidity or mortality, although they have with birth outcomes such as low birthweight and preterm birth [91,92]. Future research might benefit from being grounded in a theoretical perspective such as Critical Race Theory and incorporating measures to better clarify the role of race and ethnicity in maternal outcomes, as has already been done in birth outcomes research [90,93].

Likewise, few studies explored mechanisms which may be on the causal pathway between social determinants of health such as SEP and maternal mortality and morbidity. For example, while most studies provide robust evidence for racial and ethnic disparities in maternal outcomes, with black, Hispanic, Asian and American Indian women having consistently higher rates of maternal mortality and morbidity, few studies have examined potential underlying mechanism for these associations. Various factors could account for these disparities (Figure 1). Previous studies have shown that minority women disproportionately receive delayed or inadequate prenatal care, although disparities still exist even when this is accounted for [94]. Minority stress, perceived racism and discrimination may also affect prenatal care utilization as well as emotional and physical health [95,96]. For example, the “weathering” phenomenon—or the cumulative impact of socioeconomic disadvantages on the health of minority women—has been theorized and tested in explaining adverse birth outcomes in minorities but not in relation to maternal morbidity and severe maternal morbidity [96–98]. Inappropriate or differential care on the part of hospitals and health care providers could also contribute to disparities in care [99]. For example, studies have demonstrated that minority women deliver in different hospitals than white women, and these hospitals may have organizational models or protocols that lead to lower quality of care than the white-serving hospitals. On the other hand, even within the same hospital, minority women may also experience suboptimal care, driven by factors such as differential patterns of care or implicit bias [99]. Finally, we note that some cause-specific morbidities (e.g. postpartum hemorrhage, severe sepsis) are more prevalent in minority or disadvantaged populations, and it is unclear what determinants place them at higher risk. Future studies could assess the variability of risk and protective factors specific to these subpopulations [100]. It may also be worthwhile to identify areas of health care provider and social preventability using case reviews or social autopsies, as has been done in other countries [13,101].

Similar mechanisms may apply for underinsured women or those with a lower level of education. Uninsured or underinsured women are less likely to use obstetrical services, are more likely to have delayed or inadequate prenatal care [102,103] and may experience poorer quality of care than women with private insurance [104]. Having completed less than a high school education may also contribute to a poor health status before, during and after pregnancy and serves as a marker of SES and other lifestyle factors that impact initiation of prenatal care, maternal health literacy, and health outcomes [103]. Finally, environmental exposures, in their interaction with social determinants and neighborhood deprivation, may be a contributing factor to racial and socioeconomic disparities in maternal outcomes [105,106]. There is a growing literature connecting such exposures to maternal health conditions such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes [107,108], but their mechanisms have yet to be explored on the causal pathway to mortality and severe maternal morbidity.

We noted that most of currently available studies were retrospective cross-sectional or cohort studies using medical charts, discharge data or linked birth certificates that reiterate associations but, given the complexity of social determinants of health mechanisms, lack further evidence of what might be driving those associations. While there is a growing literature with innovative study designs in areas such as preterm birth and neonatal outcomes, there is a dearth of such designs for maternal outcomes [14]. In order to link the complex relationships among policy, social and built environment, SEP, health services and outcomes, future research might benefit from the use of frameworks common to the social determinants of health literature, such as the multilevel determinants of health [109] or life-course health development [110]. For example, a life course approach could incorporate longitudinal latent class models exploring trajectories of morbidity. A complex systems approach may also help elucidate key leverage points for intervention yet rarely has been applied to maternal health [111]. Other research approaches include following women over the lifespan or over multiple births as they change neighborhoods, states or insurance plans or leveraging changes in local or state health and social policy or trends in social determinants of health, for example through natural experiments with regression discontinuity [112,113].

Our review has identified current gaps in the literature on social determinants of health and maternal health, including the need to study a wider array of determinants, examine mechanisms that underlie these determinants, and use more diverse study designs. Challenges exist in addressing these gaps. Both maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity are relatively rare in the US, with an average of 24 deaths occurring per 100,000 live births (0.02%) and 144 cases of severe maternal morbidity occurring per 10,000 live births (1.1%) [114,115]. Further, measurement of both maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity is complicated by varying operational definitions across studies, making comparison or combination of data across place and time difficult. Similar issues plague the collection of social determinants of health data. Administrative data do not routinely record many social determinants of health outside of demographic information, limiting the range that can be studied. Even when examining the demographic information available, there is lack of consistency in data quality, such as accuracy of self-reported data or level of detail collected. It may also be difficult to design studies that can capture the complex and nuanced mechanisms through which social determinants of health may contribute to maternal outcomes. Finally, we note that many of the effect sizes in the social determinants of health literature are modest after controlling for proximal determinants, which may lead some to discount the importance of social determinants of health. However, it is worth noting that modest effects can have large population impact if the exposure is common. The use of alternative measures of effect, such as the population attributable risk, may better highlight the impact of the social determinants of health more effectively than ratio measures [116].

This review also demonstrates important concepts for women’s health providers. Obstetrician-gynecologists and other health care providers should recognize that structural determinants may influence delivery of evidence-based interventions as well as health outcomes and should address those needs as part of a preventative practice. Expert commentaries and society committee opinions encourage physicians to screen or ask patients about social challenges like employment, food insecurity and discrimination and provide them with resources early on, including legal advocacy, housing, or doula support [117–119]. Our review demonstrates that more of these social determinants of health and interventions should be studied in the maternal context. At the same time, clinicians should recognize that they themselves are part of a system that might sustain health inequities through differential care based on race, ethnicity or socioeconomic status. In these cases, collecting data on birth outcomes within institutions and identifying disparities, addressing segregated care and incorporating unconscious bias training are all steps hospital systems can take to prevent adverse maternal outcomes and enhance clinical care [120]. Ultimately, our framework suggests we must also tackle this problem from a higher level by implementing policies that target structural determinants, rooted in socioeconomic and political context [121]. Here, clinicians also can use their own experience to advocate for social change and encourage broader policy responses [118].

Our systematic review has a few limitations. First, there is no standardized MeSH search terminology for what constitutes “social determinants of health” or “maternal morbidity,” and therefore we adopted an expansive search strategy informed by recommendations from published literature. There is a possibility of missing articles, although we did our best to examine reference lists and include relevant articles from other sources. Second, we excluded some measures of “pregnancy-associated” mortality and morbidity such as those related to substance use, mental health, suicide or homicide. These are beyond the scope of this review but are no less important in contributing to maternal deaths, particularly as social determinants of health may strongly influence these indicators, pregnancy may exacerbate these conditions, and the opioid epidemic continues to grow [122,123]. Ultimately, more research is needed on these outcomes, alongside more traditional measures of maternal health. Third, there is a risk that publication bias or selective reporting of significant findings within studies may influence our conclusions. Finally, given the heterogeneity of the methodologies used, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis. As a result, our results are largely descriptive and meant to guide future research for better understanding of the social drivers of maternal outcomes, their mechanisms of association, and leverage points for intervention.

Still, this systematic review is one of the first in evaluating social determinants within the realm of maternal outcomes in the US. We conducted a comprehensive review of the current literature with multiple search strategies and purposely included “under-researched” social determinants of health indicators such as neighborhood influences and state policy to broaden the framework for how we understand maternal mortality and morbidity. We also used a validated severe maternal morbidity algorithm and included proxy outcomes for severe maternal morbidity such as readmissions and ED visits. Two reviewers screened and reviewed retrieved articles, minimizing potential reviewer bias. We also designed and registered the review protocol before conducting the literature search in order to enhance the transparency of our methods.

This systematic review identified strong evidence for the impact of race and ethnicity, insurance and education on maternal mortality and severe morbidity. However, our review importantly demonstrates a lack of diversity in the social determinants of health and maternal outcomes literature, including the type of determinants studied, type of study design, and exploration of potential mechanisms that underlie the observed associations. More needs to be done to expand the research and policy agenda to reduce inequities in rising maternal mortality and morbidity rates within the US.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Celine Soudant for her help in creating and executing the search strategy. This review was created during a summer fellowship funded by the Alpha Omega Alpha Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship and the New York Academy of Medicine David E. Rogers Student Fellowship Award.

Funding: This study was funded in part by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01MD007651) and the Blavatnik Family Foundation. The funders of this study had no role in design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Teresa M. Janevic disclosed that money was paid to her institution from the NIH, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO, CRD42018102415.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012. November 1;120(5):1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System [Internet]. CDC; 2018. [cited 2018 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Maternal_mortality_report.pdf

- 4.Chou D, Tuncalp O, Firoz T, Barreix M, Filippi V, von Dadelszen P, et al. Constructing maternal morbidity–towards a standard tool to measure and monitor maternal health beyond mortality. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016. March 2;16(45). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firoz T, Chou D, von Dadelszen P, Agarwal P, Vanderkruik R, Tuncalp O, et al. Measuring maternal health: focus on maternal morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013. August 6;91:794–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King JC. Maternal Mortality in the United States - Why Is It Important and What Are We Doing About It? Seminars in Perinatology. 2012. February 1;36(1):14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose G Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2001. June 1;30(3):427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/ConceptualframeworkforactiononSDH_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkinson RG, Marmot M, Europe WHORO for, Health (Europe) WC for U, Society IC for H and. Social determinants of health : the solid facts [Internet]. Copenhagen: : WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1998. [cited 2019 Nov 17]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/108082 [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNFPA. The Social Determinants of Maternal Death and Disability. UNFPA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Social Science & Medicine. 1994. April 1;38(8):1091–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlsen S, Say L, Souza J-P, Hogue CJ, Calles DL, Gülmezoglu AM, et al. The relationship between maternal education and mortality among women giving birth in health care institutions: Analysis of the cross sectional WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health. BMC Public Health. 2011. July 29;11(1):606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalter HD, Salgado R, Babille M, Koffi AK, Black RE. Social autopsy for maternal and child deaths: a comprehensive literature review to examine the concept and the development of the method. Population Health Metrics. 2011. August 5;9(1):45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorch SA, Enlow E. The role of social determinants in explaining racial/ethnic disparities in perinatal outcomes. Pediatric Research. 2016. January;79(1–2):141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Alton ME, Bonanno CA, Berkowitz RL, Brown HL, Copel JA, Cunningham FG, et al. Putting the “M” back in maternal–fetal medicine. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013. June 1;208(6):442–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NIH. Study Quality Assessment Tools [Internet]. NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; [cited 2018 Dec 25]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan WM, Grobman WA, Kilpatrick SJ, Main EK, D’Alton M. Facility-Based Identification of Women With Severe Maternal Morbidity. Obstet Gynecol 2014. May;123(5):978–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarlenski M, Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Simhan HN. State Medicaid Coverage of Medically Necessary Abortions and Severe Maternal Morbidity and Maternal Mortality. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017. May;129(5):786–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozhimannil KB, Graves AJ, Ecklund AM, Shah N, Aggarwal R, Snowden JM. Cesarean Delivery Rates and Costs of Childbirth in a State Medicaid Program After Implementation of a Blended Payment Policy. Medical care [Internet]. 2018; Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medp&NEWS=N&AN=29912840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring Social Class in US Public Health Research: Concepts, Methodologies, and Guidelines. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18(1):341–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson FWJ, Hogan JG, Ansbacher R. Sudden death: ectopic pregnancy mortality. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2004;103(6):1218–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, Zane SB, Green CA, Whitehead S, et al. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;103(4):729–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bateman BT, Schumacher HC, Bushnell CD, Pile-Spellman J, Simpson LL, Sacco RL, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage in pregnancy: frequency, risk factors, and outcome. Neurology. 2006. August 8;67(3):424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown HL, Chireau MV, Jallah Y, Howard D. The “Hispanic paradox”: an investigation of racial disparity in pregnancy outcomes at a tertiary care medical center. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;197(2):197.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell KH, Savitz D, Werner EF, Pettker CM, Goffman D, Chazotte C, et al. Maternal morbidity and risk of death at delivery hospitalization. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122(3):627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008–2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014. May;210(5):435.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Kuklina E, Shilkrut A, Callaghan WM. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;211(6):647.e1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang J, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. Maternal mortality in New York City: excess mortality of black women. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2000;77(4):735–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goffman D, Madden RC, Harrison EA, Merkatz IR, Chazotte C. Predictors of maternal mortality and near-miss maternal morbidity. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2007;27(10):597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hameed AB, Lawton ES, McCain CL, Morton CH, Mitchell C, Main EK, et al. Pregnancy-related cardiovascular deaths in California: beyond peripartum cardiomyopathy. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015;213(3):379.e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harper MA, Espeland MA, Dugan E, Meyer R, Lane K, Williams S. Racial disparity in pregnancy-related mortality following a live birth outcome. Annals of epidemiology. 2004;14(4):274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert P, Balbierz A, Egorova N. Paradoxical trends and racial differences in obstetric quality and neonatal and maternal mortality. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;121(6):1201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoyert DL, Danel I, Tully P. Maternal mortality, United States and Canada, 1982–1997. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2000;27(1):4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Thoma ME. Trends in Maternal Mortality by Sociodemographic Characteristics and Cause of Death in 27 States and the District of Columbia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017. May;129(5):811–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Thoma ME. Trends in Texas maternal mortality by maternal age, race/ethnicity, and cause of death, 2006–2015. Birth. 2018;45(2):169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;97(4):533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacKay AP, Berg CJ, King JC, Duran C, Chang J. Pregnancy-related mortality among women with multifetal pregnancies. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;107(3):563–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, Bateni ZH, Belfort MA, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, et al. Health Care Disparity and Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018;131(4):707–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenberg D, Geller SE, Studee L, Cox SM. Disparities in mortality among high risk pregnant women in Illinois: a population based study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saftlas AF, Koonin LM, Atrash HK. Racial disparity in pregnancy-related mortality associated with livebirth: can established risk factors explain it? American journal of epidemiology. 2000;152(5):413–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shahul S, Tung A, Minhaj M, Nizamuddin J, Wenger J, Mahmood E, et al. Racial Disparities in Comorbidities, Complications, and Maternal and Fetal Outcomes in Women with Preeclampsia/Eclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2015. November;34(4):506–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stulberg DB, Cain L, Dahlquist IH, Lauderdale DS. Ectopic pregnancy morbidity and mortality in low-income women, 2004–2008. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2016;31(3):666–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tucker MJ, Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Hsia J. The Black–White Disparity in Pregnancy-Related Mortality From 5 Conditions: Differences in Prevalence and Case-Fatality Rates. Am J Public Health. 2007. February;97(2):247–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Huang Y, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Hospital delivery volume, severe obstetrical morbidity, and failure to rescue. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;215(6):795.e1–795.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morong JJ, Martin JK, Ware RS, Robichaux AG 3rd. A review of the preventability of maternal mortality in one hospital system in Louisiana, USA. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2017;136(3):344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hopkins FW, MacKay AP, Koonin LM, Berg CJ, Irwin M, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality in Hispanic women in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999;94(5 Pt 1):747–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sundaram V, Liu K-L, Laraque F. Disparity in maternal mortality in New York City. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972). 2005;60(1):52–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siddiqui M, Minhaj M, Mueller A, Tung A, Scavone B, Rana S, et al. Increased Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Asian American and Pacific Islander Women in the United States. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2017;124(3):879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Admon LK, Winkelman TNA, Zivin K, Terplan M, Mhyre JM, Dalton VK. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Incidence of Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States, 2012–2015. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018. November;132(5):1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibson C, Rohan AM, Gillespie KH. Severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2017;116(5):259–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gray KE, Wallace ER, Nelson KR, Reed SD, Schiff MA. Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2012;26(6):506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lima FV, Parikh PB, Zhu J, Yang J, Stergiopoulos K. Association of cardiomyopathy with adverse cardiac events in pregnant women at the time of delivery. JACC Heart failure. 2015;3(3):257–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lyndon A, Lee HC, Gilbert WM, Gould JB, Lee KA. Maternal morbidity during childbirth hospitalization in California. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2012;25(12):2529–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madan I, Puri I, Jain NJ, Grotegut C, Nelson D, Dandolu V. Characteristics of obstetric intensive care unit admissions in New Jersey. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2009;22(9):785–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Papillon-Smith J, Imam B, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. Population-based study on the effect of socioeconomic factors and race on management and outcomes of 35,535 inpatient ectopic pregnancies. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2014;21(5):914–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reid LD, Creanga AA. Severe maternal morbidity and related hospital quality measures in Maryland. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association [Internet]. 2018; Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medp&NEWS=N&AN=29593355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown HL, Small M, Taylor YJ, Chireau M, Howard DL. Near miss maternal mortality in a multiethnic population. Annals of epidemiology. 2011;21(2):73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frederiksen BN, Lillehoj CJ, Kane DJ, Goodman D, Rankin K. Evaluating Iowa Severe Maternal Morbidity Trends and Maternal Risk Factors: 2009–2014. Maternal and child health journal. 2017;21(9):1834–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Janevic T, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Severe maternal morbidity among Hispanic women in New York City: Investigation of health disparities. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017. February 1;129(2):285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lazariu V, Nguyen T, McNutt LA, Jeffrey J, Kacica M. Severe maternal morbidity: A population-based study of an expanded measure and associated factors. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2017;12(8). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85026881724&doi=10.1371%2fjournal.pone.0182343&partnerID=40&md5=65eee2e9d864a2b272401d3160d62e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hebert PR, Reed G, Entman SS, Mitchel EF Jr, Berg C, Griffin MR. Serious maternal morbidity after childbirth: prolonged hospital stays and readmissions. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999;94(6):942–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee W-C, Phillips CD, Ohsfeldt RL. Do rural and urban women experience differing rates of maternal rehospitalizations? Rural and remote health. 2015;15(3):3335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bacak SJ, Callaghan WM, Dietz PM, Crouse C. Pregnancy-associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1999–2000. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;192(2):592–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Batra P, Fridman M, Leng M, Gregory KD. Emergency Department Care in the Postpartum Period: California Births, 2009–2011. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;130(5):1073–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheesman K, Brady JE, Flood P, Li G. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related complications in labor and delivery, New York State, 2002–2005. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009;109(4):1174–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cahill AG, Stamilio DM, Odibo AO, Peipert J, Stevens E, Macones GA . Racial disparity in the success and complications of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;111(3):654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oud L, Watkins P. Evolving trends in the epidemiology, resource utilization, and outcomes of pregnancy-associated severe sepsis: a population-based cohort study. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2015;7(6):400–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rush B, Martinka P, Kilb B, McDermid RC, Boyd JH, Celi LA. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Pregnant Women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017;129(3):530–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Frolich MA, Banks C, Brooks A, Sellers A, Swain R, Cooper L. Why do pregnant women die? A review of maternal deaths from 1990 to 2010 at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2014;119(5):1135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oleske DM, Linn ES, Nachman KL, Marder RJ, Sangl JA, Smith T. Effect of Medicaid managed care on pregnancy complications. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2000;95(1):6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Acosta CD, Knight M, Lee HC, Kurinczuk JJ, Gould JB, Lyndon A. The Continuum of Maternal Sepsis Severity: Incidence and Risk Factors in a Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2013;8(7). Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84879750586&doi=10.1371%2fjournal.pone.0067175&partnerID=40&md5=c654acfed854b16c4dd1ababe0fd24e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Esakoff TF, Rad S, Burwick RM, Caughey AB. Predictors of eclampsia in California. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2016;29(10):1531–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lanska DJ, Kryscio RJ. Risk factors for peripartum and postpartum stroke and intracranial venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2000;31(6):1274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ehrenthal DB, Chichester ML, Cole OS, Jiang X . Maternal Risk Factors for Peripartum Transfusion. Journal of Women’s Health. 2012. April 13;21(7):792–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stulberg DB, Zhang JX, Lindau ST. Socioeconomic disparities in ectopic pregnancy: predictors of adverse outcomes from Illinois hospital-based care, 2000–2006. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(2):234–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coghill AE, Hansen S, Littman AJ. Risk factors for eclampsia: a population-based study in Washington State, 1987–2007. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;205(6):553.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tan H, Wen SW, Walker M, Demissie K. Missing paternal demographics: A novel indicator for identifying high risk population of adverse pregnancy outcomes. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2004;4(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith BL, Sandlin AT, Bird TM, Steelman SC, Magann EF. Maternal mortality in the Mississippi Delta region. Southern medical journal. 2014;107(5):275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guendelman S, Thornton D, Gould J, Hosang N. Social disparities in maternal morbidity during labor and delivery between Mexican-born and US-born White Californians, 1996–1998. American journal of public health. 2005;95(12):2218–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.El Kady D, Gilbert WM, Xing G, Smith LH. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of assaults during pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;105(2):357–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: maternal complications and birth outcomes. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1999;93(5 Pt 1):661–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: associations with maternal and neonatal health. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2006;195(1):140–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nelson DB, Moniz MH, Davis MM. Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the United States, 1997–2012. BMC Public Health. 2018. August 13;18(1):1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Friedman AM, Wright JD, Ananth CV, Siddiq Z, D’Alton ME, Bateman BT. Population-based risk for peripartum hysterectomy during low- and moderate-risk delivery hospitalizations. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;215(5):640.e1–640.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nethery E, Gordon W, Bovbjerg ML, Cheyney M. Rural community birth: Maternal and neonatal outcomes for planned community births among rural women in the United States, 2004–2009. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2018;45(2):120–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hughes S, Zweifler JA, Garza A, Stanich MA. Trends in rural and urban deliveries and vaginal births: California 1998–2002. The Journal of rural health : official journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association. 2008;24(4):416–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016. January 1;214(1):122.e1–122.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016. August 1;215(2):143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]