Abstract

The Fontan procedure is a successful palliation for single ventricle defect. Yet, a number of complications still occur in Fontan patients due to abnormal blood flow dynamics, necessitating improved flow analysis and treatment methods. Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has emerged as a suitable method for such flow analysis. However, limitations on altering physiological blood flow conditions in the patient while in the MRI bore inhibit experimental investigation of a variety of factors that contribute to impaired cardiovascular health in these patients. Furthermore, resolution and flow regime limitations in phase contrast (PC) MRI pose a challenge for accurate and consistent flow characterization. In this study, patient-specific physical models were created based on nine Fontan geometries and MRI experiments mimicking low- and high-flow conditions, as well as steady and pulsatile flow, were conducted. Additionally, a particle image velocimetry (PIV)-compatible Fontan model was created and flow was analyzed with PIV, arterial spin labeling (ASL), and four-dimensional (4D) flow MRI. Differences, though nonstatistically significant, were observed between flow conditions and between patient-specific models. Large between-model variation supported the need for further improvement for patient-specific modeling on each unique Fontan anatomical configuration. Furthermore, high-resolution PIV and flow-tracking ASL data provided flow information that was not obtainable with 4D flow MRI alone.

Keywords: Fontan, TCPC, 4D flow MRI, particle image velocimetry, arterial spin labeling

Introduction

Congenital heart diseases that require ongoing care occur in approximately 6 out of every 1000 births. Approximately 8% of these congenital heart diseases cases can be attributed to single ventricle defects, conditions that are characterized by an underdeveloped ventricle, or missing cardiac valves [1,2]. Single ventricle defects are often treated by creating a cavopulmonary connection (referred to as the Fontan), which facilitates passive return of blood to the pulmonary circulation with only one system pump. The Fontan connection greatly improves the health and lifespan of the patient. However, due to the highly modified circuit, long-term complications occur, such as thrombus formation, arrhythmia, enteropathy, chronic effusions, artero-venous malformations, ventricular failure, and decreased exercise capacity [1,2]. The flow dynamic factors leading to these complications are still not fully understood. However, advancements in medical imaging and numerical methods offer the potential for better understanding of Fontan flow analysis and improved prediction of the hemodynamic effects of the Fontan procedure [3–8].

A major consideration in the analysis of Fontan flow dynamics is the fact that every cavopulmoanry connection is highly patient specific. Therefore, a general analysis of Fontan geometry, flow dynamics, and their impact on Fontan function will not apply to every Fontan patient. Furthermore, physiological variations, such as increased or decreased blood flow due to physical stress, modified flow through the pulmonary circuit due to the abnormal cardiac function, and altered geometry will elicit responses unique to each patient. One particularly relevant physiological issue in Fontan patients is intolerance to elevated blood flow, which is almost inevitable in this patient group due to a number of factors that cause a decline in performance before clinical complications become relevant [9–12]. Flow abnormalities become more dramatic at increased heart rates, as seen during exercise. There are a number of potential reasons for these abnormalities. Before the Fontan procedure, cardiac dilation and hypertrophy develop. The ventricle remains overgrown after the procedure, but now has a reduced preload, leaving a situation of incomplete filling and low cardiac output. Additionally, the afterload is increased by elevated systemic vascular resistance and pulmonary vascular resistance in series with reduced mechanical efficiency of only one pump [11,13,14]. Pulmonary health can even be further affected by the abnormal flow entering the pulmonary vascular tree through the Fontan. Because there is no functioning ventricle pumping directly to the pulmonary circuit, the pulmonary flow is much more steady (less pulsatile) in Fontan patients than in their healthy counterparts. It has been hypothesized that pulsatile flow is essential for pulmonary vascular health, and that without it negative adaptations can occur in the pulmonary vasculature [15,16]. Furthermore, uneven flow distribution from the vena cava to the right and left pulmonary arteries (through the Fontan connection) has been hypothesized to negatively impact pulmonary health through the development of aterovenous malformations [4,17,18].

Several studies have worked to understand and predict specific flow features using patient-specific phase contrast (PC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data and computational tools to develop more realistic numerical and physical models of Fontan flow [3,5,6,19–21]. Phase contrast MRI, in particular, has shown to be a very useful tool in analysis of Fontan flow features such as pulmonary flow distribution, energy loss calculations, and even flow dynamics of the single ventricle itself [20,21]. However, limits on exercising Fontan patients in the MRI bore, and altering physiological conditions in general, inhibit analysis of the individual contributions of confounding factors in Fontan flow. Numerical studies have added capabilities in such analyses with the ability to easily change inlet and outlet flow conditions to match physiological variation and by providing much higher spatial and temporal flow resolution. However, assumptions on geometry and idealized flow conditions can affect accuracy and hinder clinical applicability. Furthermore, numerical methods require accurate boundary conditions that must be obtained through other methods. Physical experimental models may provide a solution to some of the limitations of in vivo and computational analyses [22]. Not only do experiments allow for alterations in geometry and flow conditions to emulate physiological variation that cannot be produced in vivo in the MRI scan room, but they also provide a physically real flow field that can be analyzed with high-resolution flow analysis methods, such as particle image velocimetry [23]. Furthermore, models can be used to validate data collection methods. In addition to phase contrast MRI, another MRI method, known as arterial spin labeling (ASL), may provide valuable information on physiological blood flow distribution through its capability of tagging and tracking blood flow though the vasculature [24–26]. However, this too must be validated.

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the utility and feasibility of in vitro patient-specific flow analysis during altered physiological flow conditions. To do this, additive manufacturing methods were used to produce a variety of patient-specific Fontan vessel geometries. Multiple flow pumps were then used to create a range of physiological flow conditions so that the effects of each condition on Fontan flow dynamics could be analyzed. Data were collected with four-dimensional (4D) flow phase-contrast MRI, arterial spin labeling, and high-resolution particle image velocimetry to demonstrate the flow features that can be resolved and analyzed in these Fontan models.

Methods

Human Subjects.

In this Institutional Review Board-approved and health insurance portability and accountability act-compliant study, anatomical MRI data from nine subjects [21] (23.6 ± 6.5 years old, 64.7±6.1 kg) with a Fontan connection for palliation of single ventricle defect were used.

Human Subject MR Imaging.

Four-dimensional flow MRI was performed on the nine subjects with a 3 T system (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare) using PC-VIPR [27] prescribed over a large chest imaging volume (FOV = 32 × 32 × 32 cm3, TR/TE = 5.5/2.3 ms, α = 15 deg, Venc = 150 cm/s, projection number ≈ 22,000, scan time: 11 min 30 s). Contrast was administered in each patient based on body surface area (range: 6.8–20 mL of Gadofosveset trisodium or Gadobenate dimeglumine). Contrast not only helped in the in vivo image analysis (detailed in Ref. [21]), but also aided in definition of anatomical boundaries for physical model creation.

Fontan Model Fabrication

Rigid Flow Models for Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measurements.

The Fontan connection anatomy of each subject was segmented from time-averaged images using semi-automatic segmentation software (mimics, Materialize, Leuven, Belgium), through which a three-dimensional (3D) geometry was generated from the phase contrast angiograms obtained from 4D MR imaging (Fig. 1(a)). Subsequently, design software (3-matic, Materialize, Leuven, Belgium) was used to cut inlet vena cava and outlet pulmonary artery vessels normal to the smoothed vessel flow path. An external wall thickness was added around the blood flow path, and the inner blood flow volume was subtracted. Tube connectors were virtually added to each inlet and outlet vessel to complete the virtual 3D model (Fig. 1(b)).

Fig. 1.

Rigid Fontan models for flow experiments were created with the following steps: (a) the blood flow paths of each patient were segmented from MRI data, (b) a thin-walled flow model was designed with perfusion tube connectors, (c) the model was 3D printed with a powder bed fusion methods and connected to perfusion tubing, and (d) the model was surrounded with a polyurethane resin to improve MRI signal-to-noise ratio. SVC—superior vena cava; IVC—Inferior vena cava; LPA—left pulmonary artery; RPA—right pulmonary artery.

The nine virtual Fontan models (shown in Fig. 2) were saved in steriolithography format and used to fabricate physical models using powder bed fusion, an additive manufacturing method that employs a laser to melt polymer particles into the desired shape, layer by layer. The powder bed fusion equipment (DTM Sinterstation 2500CI ATC, 3D Systems, Inc., Rock Hill, SC) setup included 12 W laser power, 0.15 mm scan spacing, 5080 mm/s beam speed, and nylon 11 powder. Flexible surgical bypass tubing was fixed to the connectors of the printed rigid models, which were placed in a plastic container (Fig. 1(c)). A polyurethane resin was then poured around each model to improve signal-to-noise ratio during MRI experiments (Fig. 1(d)).

Fig. 2.

Cavopulmonary connection flow path geometries of nine Fontan patients were segmented and used to create physical flow models for flow experiments. Note the high variability between anatomical configurations.

Transparent Silicone Model for Particle Image-Velocimetry, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Arterial Spin Labeling Measurements.

One of the Fontan virtual flow geometries (model 5) was used to create a semiflexible optically clear model for experimental particle image-velocimetry (PIV) and ASL comparison with 4D flow MRI. To do this, the Fontan model flow path was again prepared in 3-matic software by virtually fixing negative profiles of tube connectors normal to inlet and outlet vessel flow paths (Fig. 3(a)). The virtual flow path profile was then fabricated with a fused-deposition modeling machine (Ultimaker 3, Ultimaker, Cambridge, MA) using a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) material. The printed part was fixed in a poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) box and surrounded with silicone resin (Sylguard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI). When the resin had cured, the poly methyl methacrylate box was removed and the Silone block (Fig. 3(b)) was submerged in water to dissolve the inner PVA core. When the PVA core had dissolved (Fig. 3(c)), connectors were fixed inside the model for perfusion tube mounting. Only one transparent PIV model was created because of the lengthy model creation, experiment setup and calibration, and data analysis processes involved with PIV.

Fig. 3.

A semiflexible, transparent Fontan model for flow experiments was created with the following steps: (a) a blood flow path core was created from segmented patient-specific Fontan data and 3D printed with a dissolvable polyvinyl alcohol material, (b) the 3D printed core was fixed in an acrylic box and surrounded by silicone resin, resulting in a cured silicone block, and (c) the blood flow path core was dissolved from the silicone block, leaving an optically clear model compatible with particle image velocimetry and MRI

Experimental Setup

Low Versus High Flow Magnetic Resonance Imaging Experiment Setup.

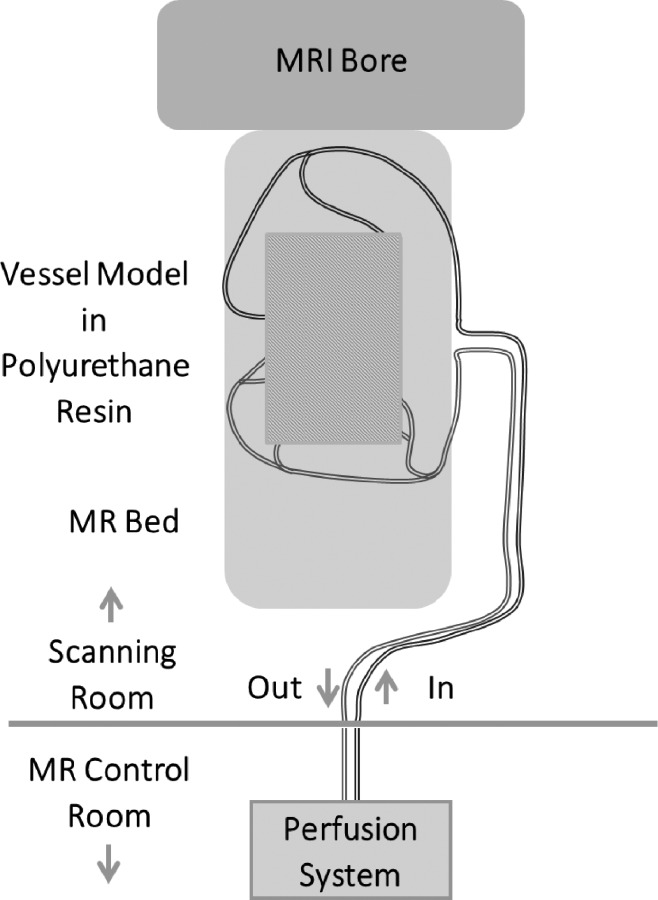

Each of the nine rigid Fontan model was connected to a perfusion pump (Stockert SIII Heart-Lung Machine) using surgical tubing. The model setups were then brought into the MRI scan room and placed in the scanner bed, as shown in Fig. 4. Water was pumped through each model at system steady flow rates intended to simulate rest (2 LPM) and exercise (3 LPM) of Fontan patients. These flows rates were determined based on two main factors: (1) the measured in vivo Fontan flow rates (0.5–2.5 L/min) and (2) published data on Fontan flow increases during exercise [28].

Fig. 4.

The Fontan flow models were integrated into a flow loop with either a steady perfusion pump or a pulsatile pump system. The model was then brought into the MRI scanning room and oriented on the scanning bed. The perfusion and pulsatile pumping systems were monitored from the MR control room as PC-MRI protocols were run.

Pulsatile Flow Experiment Setup.

To compare flow features in the Fontan models between continuous and pulsatile flow conditions, the MRI experiments were repeated on five of the Fontan models with a pulsatile pump system. To do this, five of the rigid models were individually connected to a positive displacement pulsatile pump (BDC PD-1100, BDC Laboratories, Wheat Ridge, CO). An input sinusoidal waveform was used with an average flow rate of 2 l per minute, a period of 1 s (relating to a heart rate of 60 beats per minute), and an amplitude of 16.5 mL. Only five of the models were used for this experiment due to scan time restrictions at the time that this portion of the study was added.

Particle Image-Velocimetry, Four-Dimensional Flow Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Arterial Spin Labeling Experimental Setup.

The transparent silicone model was connected to the pulsatile pump system in the same manner as the rigid models. For 4D flow MRI and ASL measurements, the model was placed on the MRI scanner bed, as described in the “low versus high flow MRI experiment setup” section previously and as depicted in Fig. 4. For PIV experiments, the model was fixed in place in the PIV experimental setup at an equivalent vertical height as the MRI scanner bed (to avoid pressure differences in the system). A sinusoidal inlet flow waveform with an average flow rate of 2 l per minute, a period of 1 s, and an amplitude of 16.5 mL was used for all experiments.

Data Acquisition

Four-Dimensional Flow Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Identical MRI scanning procedures were used across all Fontan model experiments for both silicone and rigid models. The experiments were conducted on a clinical 3 T MRI system (Discovery MR 750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with a 32-channel body coil (NeoCoil, Pewaukee, WI). Cardiac-gated time-resolved 3D radially undersampled PC acquisition (five-point PC-VIPR) [11] with increased velocity sensitivity performance was used to obtain a 4D velocity map [4,11]. MR imaging volume was 32 × 32 × 24 cm with spherical encoding, isotropic spatial resolution was 1.25 mm, TR/TE were 6.4 and 2.2 ms, respectively. Remaining acquisition parameters included:, α = 15 deg, Venc = 150 cm/s, projection number ≈ 22,000, and a scan time of 11 min 30 s

Phase contrast MRI data were reconstructed into 14 time frames per cardiac cycle. Automatic correction was performed on phase offsets for Maxwell terms and eddy currents during reconstruction [1,24]. Second-order polynomial fitting of background tissue was used for eddy current correction [24]. Velocity-weighted angiograms were calculated from the velocity and magnitude data [10].

Particle Image Velocimetry.

A Flowmaster PIV system (LaVision, Göttingen, Germany) was used to acquire tomographic particle image velocimetry data in the silicone Fontan model. The system included a dual-pulse 527 nm Nd:YLF laser (Photonics Industries International, Inc., Long Island, NY) and three high-speed cameras (Phantom v341, Vision Research, Wayne, NJ). A glycerol–water mixture was used to match the index of refraction of the silicone model. As a result, working fluid parameter included a density of 1113.5 kg/m3 and a viscosity of 0.0045 kg/m s. Double-frame images were recorded during laser illumination (Fig. 5) at a frame rate of 402 Hz, with time separation of 230 μs for a maximum fluid particle displacement of 152 μm. A total of 600 sets of images were acquired to ensure the inclusion of a complete cardiac cycle (1 s). This resulted in 1.5 s of acquisition time. The images were preprocessed using subtraction of a mean intensity image and Gaussian smoothing (3 × 3) to eliminate refractive index errors. Resulting spatial resolution was 0.14 × 0.14 × 0.14 mm.

Fig. 5.

Tomographic particle image velocimetry experiments were performed on the transparent silicone Fontan model. Flow data were analyzed in the illuminated volume.

Arterial Spin Labeling.

An accelerated ASL angiography sequence, which combines pseudo-continuous ASL (PCASL) [26] labeling with an accelerated 3D radial acquisition, was performed on a clinical 3 T scanner (Discovery MR 750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with a 32-channel body coil (NeoCoil, Pewaukee, WI). The images were collected in the silicone Fontan model using two labels. The first label was superior to the Fontan, tagging the superior vena cava (SVC), and the second was inferior to the Fontan, tagging the inferior vena cava (IVC). Parameters include 2 mm isotropic resolution, 200 ms temporal resolutions, 0 s postlabeling delay, 1 s tagging time, 5 mm offset based on the edge of the field of view for the Fontan model, four frames per tag acquired with a LookLlocker 3D radial acquisition, and total scan time of 10 min (5 min per plane).

Data Analysis

Flow Quantification.

The 4D flow MRI data were exported to fluid flow quantification and visualization software (ensight, CEI), where cut planes were placed perpendicular to the main vessel flow paths. Model vessels of interest included the SVC, IVC, left pulmonary artery (LPA), and right pulmonary artery (RPA). Velocity vectors were generated across each model to visualize flow patterns. Metrics of flow (mL/min) were computed from the velocity data at key regions of interest. Vorticity was also calculated at regions of interest by calculating the magnitude of the three components of flow rotation as follows:

| (1) |

In these equations, ω represents vorticity and u, v, and w represent the velocities in the x, y, and z coordinate directions, respectively. Another related parameter, helicity, was also quantified. Helicity was calculated by the equation

| (2) |

where v is the blood velocity and ω is vorticity. In an attempt to quantify the differences in the helical flow patterns between models and experiments, the vorticity and helicity were calculated from the imaging and experimental velocity data in ensight (CEI, Apex, NC). Helicity was measured by volume by segmenting the regions of the Fontan model flow volume and then imposing the volume in ensight. Vorticity was measured in cut planes placed at locations throughout the Fontan model.

For analysis of the effects of pulsatile and nonpulsatile flow on Fontan model flow dynamics, the oscillatory shear index (OSI) was also quantified. OSI is a dimensionless parameter that represents how well the wall shear stress vector is aligned with the time-averaged wall shear stress over the experimental cycle (one cardiac cycle in this work). OSI was calculated as follows [29]:

| (3) |

where is the wall shear stress vector and T is the length of the experimental cycle from the flow pump.

Streamline Distribution Determination.

To analyze the distribution of flow through each Fontan model pulmonary branch, particle traces were emitted from the IVC and SVC cut planes in Ensight to produce streamlines. Particle seeding count was kept at a constant 300 particle traces per vessel cut plane (average of 1.4 particle traces per mm2), based on a previous seeding count study [30]. Data were averaged over each experimental cycle, Therefore, flow was analyzed as “steady,” and streamlines were representative of the fluid particle paths. Streamlines were analyzed by quantifying the number of particle traces that flowed through each plane of the model. The number of traces passing through each pulmonary branch were then recorded and categorized based on their origin (IVC or SVC), and streamline distributions were calculated. Note that this analysis was not performed on the PIV dataset, as data from the full model volume cannot be resolved with the current PIV acquisition method.

Statistics.

Differences in flow, vorticity, oscillatory shear index, and pulmonary streamline distribution were assessed using Student's paired t-tests and were considered significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05). A Mann–Whitney test was also performed to see the impact on statistical results; however, the significance of variable relationships was not changed with this analysis.

Results

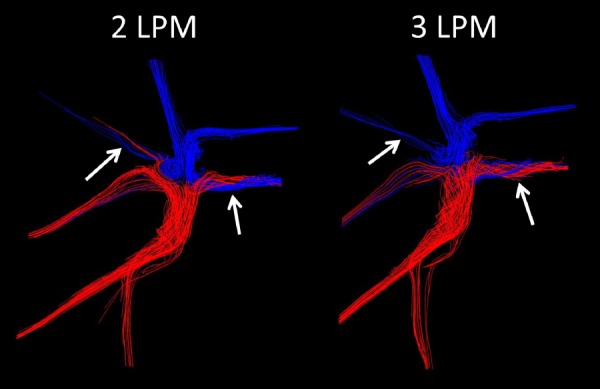

Four-dimensional flow MRI-derived streamlines through representative rigid models at high and low flow conditions are shown is Fig. 6. Large variation in flow patterns was observed between models. As shown in Fig. 7, a nonsignificant (p = 0.46) difference in path line distribution from each vena cava inlet to the pulmonary artery outlets was observed between rest (low flow) and exercise (high flow) conditions. Total flow distributions between the left and right pulmonary artery outlets also varied between flow conditions, though the difference was not significant (p = 0.13). Furthermore, a significant difference between flow conditions was not observed in vorticity or helicity metrics. However, it was observed that increases in vorticity and helicity were not proportional to the magnitude as the flow increase.

Fig. 6.

Velocity streamlines through four patient-specific Fontan models with flow rates simulating resting and exercise conditions

Fig. 7.

Pulmonary streamline distribution through a Fontan model at resting (2 LPM) and exercise (3 LPM) conditions

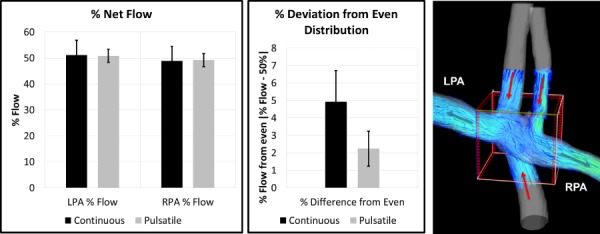

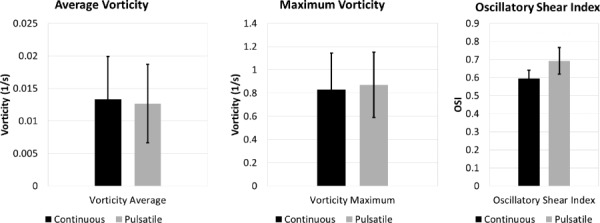

Upon analysis of the pulsatile-versus-laminar flow experiments in five rigid Fontan models, some nonsignificant model-specific pulmonary flow distribution differences were observed between flow conditions. As shown in Fig. 8, pulsatile flow led to a more even distribution between the RPA and LPA flow. This difference was greater in some models than in others, as shown in Fig. 9. Nonetheless, when considering the behavior of all models as a whole, the difference in flow distribution was not statistically significant. Furthermore, although model-specific differences were observed in vorticity and helicity between flow conditions, there was no significant difference between flow types in average vorticity (p = 0.36) or maximum vorticity (p = 0.70), or wall shear stress (p = 0.23) across models (Fig. 10). However, there was a significant difference in oscillatory shear index (p = 0.003) between pulsatile and steady flow experiments.

Fig. 8.

Pulmonary flow distributions from continuous flow and pulsatile flow experiments suggested that pulsatile flow led to a more evenly distributed flow in these models

Fig. 9.

Individual model results displaying pulmonary flow distributions from continuous flow and pulsatile flow experiments. Results suggest that pulsatile flow leads to a more even pulmonary flow distribution in these models.

Fig. 10.

Although there was high individual model variability between experimental conditions, no significant differences were observed in vorticity or shear stress metrics between continuous and pulsatile flow experiments when models were analyzed as a group

The results of the flow analysis on the silicone Fontan model displayed good qualitative agreement in general Fontan flow distribution between 4D flow MRI and ASL. However, note that ASL results displayed a unique mixing junction (merging of IVC and SVC flow streams) near the convergence of the inlet and outlet vessels that was not observed in the 4D flow data (Fig. 11). Silicone model 4D flow distribution results agreed well with in vivo 4D flow MRI results from previous work. When the same model was analyzed with particle image velocimetry (Fig. 12), finer flow structures and patterns were successfully resolved. As shown in Figs. 12 and 13, PIV results provided additional high-resolution insight into vortical and helical flow patterns that could not be fully visualized with 4D flow MRI and ASL, especially in regions of low net flow.

Fig. 11.

Pulmonary flow distribution was visualized and compared between in vivo patient 4D flow MRI, in vitro silicone model 4D flow MRI, and ASL methods

Fig. 12.

Velocity vectors in the confluence of a silicone Fontan model obtained with PIV and 4D flow MRI. There is good agreement in general flow patterns in this area of high velocity.

Fig. 13.

Velocity vectors in the left pulmonary artery branch of a silicone Fontan model obtained with PIV and 4D flow MRI. Note the higher flow resolution obtained with PIV in areas of low velocity.

Discussion

Analysis of Fontan flow under varying physiological conditions is a challenge due to the difficulty of inducing flow magnitude changes due to physiological stress in Fontan patients while they are in the magnet bore. Furthermore, the dynamics of multiple components of the cardiovascular system (inlet flow from the vena cava, Fontan geometry, pulmonary resistance, system pressure, etc.) make it difficult to sort through the many confounding factors that contribute to altered blood flow regimes. In this study, physical models representative of a variety of patient-specific Fontan anatomies were used to analyze the effects of varying flow conditions. Furthermore, a Fontan geometry was created that could be used to provide high-resolution flow data and particle tracking flow distribution data with particle image velocimetry and arterial spin labeling. Such data can be used to supplement and validate common flow imaging metrics, such as 4D flow MRI.

Flow patterns and hemodynamic metrics during low flow (rest) and high flow (exercise) conditions were analyzed using rigid models of anatomically accurate patient vasculature. Results showed that higher flow rates, as seen during exercise, can change flow patterns and fluid distributions in individual Fontan connection models. Furthermore, changes unique to each model occurred in vorticity and helicity metrics between flow conditions, suggesting potential transitional flow development. If the same hemodynamic alterations occur in vivo, the efficiency of the connection and flow distribution through the pulmonary circulation may be altered in the Fontan patient during exercise. Results of the pulsatile-versus-steady flow experiments also provided potentially useful insight into the behavior of flow distribution in Fontan geometries. It was observed that pulsatile inlet flow led to a more even (closer to 50-50 between LPA and RPA) flow distribution than did the continuous flow. We hypothesize that this is due to the higher flow amplitude that occurs for the same average flow rate in pulsatile flow. At the peak of the wave pulse, a high amount of flow may be forced through both branches of the Fontan geometry. However, in continuous flow, a submaximal peak flow may not be enough to force flow through both pulmonary branches, leading to a passive flow that travels primarily through the path of least resistance. Combining such maldistribution with a lack of pulsatile arterial signaling may be contributing to the pulmonary complications that are often observed in Fontan patients.

It is again important to note that the anatomical configuration of each Fontan connection was unique. This made generalized conclusions on the flow–geometry relation difficult, particularly when adding in varying flow conditions. Although no significant relationships were observed among common anatomical features and flow in these Fontan models, such relationships have been observed in this patient group in vivo [21]. It is expected that a larger sample of geometrically similar models, and a greater number of flow experiments, would be beneficial for uncovering such relationships with experimental analysis.

Experiments on the semiflexible transparent silicone Fontan model demonstrated the variety of flow parameters that can be analyzed both in vivo and in vitro. As represented in Fig. 11, patient-specific Fontan flow distribution can be analyzed and validated with in vivo and in vitro 4D flow MRI and ASL. Flow distribution results on the model analyzed in this study displayed good agreement in pulmonary flow distribution between these methods. With more development, ASL may provide valuable flow-tracking information in a variety of cardiovascular territories. Furthermore, with the addition of high-resolution in vitro data from PIV, a number of unique flow features can be visualized and quantified to supplement and validate medical image data. As observed through our results, particle image velocimetry data provided highly detailed flow field information that could not be resolved with 4D flow MRI. This was particularly true in areas of low flow, such as in the middle of flow vortices (Fig. 12) and in recirculation regions of pulmonary artery branches (Fig. 13). This is typical of 4D flow MR imaging, as the requirement of fixing velocity encoding settings prior to scanning can inhibit the resolution low or high velocity fields. PIV does not have this limitation, allowing for the resolution of multiple flow regimes in a single data collection.

There are a number of current limitations of this study that warrant discussion. First of all, the anatomical models used for these experiments were isolated from upstream and downstream effects that are present in vivo. Future experiments will include adjustable resistance and compliance elements that can be matched with physiological conditions. Additionally, rigid models were used for most of this study. Although flow-induced motion effects are often small in the area of the total cavopulmonary connection (TCPC), physiologically realistic wall properties warrant further investigation. The rigid tube perfusion connections also imposed a limitation by creating unrealistically strong flow jets at the vena cava inlets. Furthermore, the wide range of Fontan geometries and patient-specific flow conditions limited the group analysis that could be done on this set of models, which can affect the applicability of the results of this study to patient application at this stage of development. However, it is important to note that this also shows the importance of patient-specific analysis on Fontan flow by demonstrating the large range of unique flow regimes and flow features that are produced in each flow path. Finally, we are currently limited in simultaneous quantitative comparison between 4D flow MRI, ASL, and PIV. 4D flow MRI gives us simultaneous velocity information throughout the entire geometry of interest due to the large volumetric coverage that we can acquire and the ability to do cardiac gating to the experimental pump input waveform. Unfortunately, we cannot currently compare bulk flow measures and distributions between 4D flow MRI and PIV due to the limitation of needing to select a small volume of interest for PIV analysis. Likewise, velocity is not compared between these two methods and ASL, as our ASL method had the purpose of tracking flow distribution, and not individual velocity vectors. Yet, we could make a visual comparison in this work, as we continue to develop quantitative comparison methods between these three modalities.

Conclusion

Patient-specific Fontan flow model experiments were conducted to study the effects of varying flow conditions on flow patterns in cavopulmonary connection geometries and to demonstrate the utility of ASL and high-resolution PIV for the analysis of Fontan flow. Although high variability between flow model data made flow generalizations difficult, it also showed the importance of patient-specific modeling for this patient population. Future goals of this work will be to further develop these methods to create an analysis and planning tool for Fontan flow and the Fontan procedure.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the funding by AHA grant 14SDG19690010 (AR), NIH awards UL1TR000427 and TL1TR000429NIH, and GE Healthcare for their assistance and support. Furthermore, this investigation was, in part, supported by the National Institutes of Health, under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 HL 007936 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Cardiovascular Research Center.

Funding Data

AHA Grant 14SDG19690010, NIH awards UL1TR000427 and TL1TR000429NIH, and research assistance from GE Healthcare (Funder ID: 10.13039/100000002).

The National Institutes of Health, under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 HL 007936 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Cardiovascular Research Center.

Glossary of Abbreviations

- ASL =

arterial spin labeling

- FOV =

field of view

- IVC =

inferior vena cava

- LPA =

left pulmonary artery

- MRI =

magnetic resonance imaging

- PC-VIPR =

phase-contrast vastly undersampled isotropic projection reconstruction

- PIV =

particle image velocimetry

- RPA =

right pulmonary artery

- SVC =

superior vena cava

- TE =

echo time

- TR =

repetition time

- Venc =

velocity encoding

- 4D =

four-dimensional

References

- [1]. Collins, R. T. , Doshi, P. , Onukwube, J. , Fram, R. Y. , and Robbins, J. M. , 2016, “ Risk Factors for Increased Hospital Resource Utilization and in-Hospital Mortality in Adults With Single Ventricle Congenital Heart Disease,” Am. J. Cardiol., 118(3), pp. 453–462. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Khairy, P. , Fernandes, S. M. , Mayer, J. E. , Triedman, J. K. , Walsh, E. P. , Lock, J. E. , and Landzberg, M. J. , 2008, “ Long-Term Survival, Modes of Death, and Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Fontan Surgery,” Circulation, 117(1), pp. 85–92. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.738559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Lardo, A. C. , Webber, S. A. , Friehs, I. , del Nido, P. J. , and Cape, E. G. , 1999, “ Fluid Dynamic Comparison of Intra-Atrial and Extracardiac Total Cavopulmonary Connections,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 117(4), pp. 697–704. 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70289-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Bächler, P. , Valverde, I. , Pinochet, N. , Nordmeyer, S. , Kuehne, T. , Crelier, G. , Tejos, C. , Irarrazaval, P. , Beerbaum, P. , and Uribe, S. , 2013, “ Caval Blood Flow Distribution in Patients With Fontan Circulation: Quantification by Using Particle Traces From 4D Flow MR Imaging,” Radiology, 267(1), pp. 67–75. 10.1148/radiol.12120778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Markl, M. , Geiger, J. , Kilner, P. J. , Föll, D. , Stiller, B. , Beyersdorf, F. , Arnold, R. , and Frydrychowicz, A. , 2011, “ Time-Resolved Three-Dimensional Magnetic Resonance Velocity Mapping of Cardiovascular Flow Paths in Volunteers and Patients With Fontan Circulation,” Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg., 39(2), pp. 206–212. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Long, C. C. , Hsu, M. C. , Bazilevs, Y. , Feinstein, J. A. , and Marsden, A. L. , 2012, “ Fluid-Structure Interaction Simulations of the Fontan Procedure Using Variable Wall Properties,” Int. J. Numer. Method Biomed. Eng., 28(5), pp. 513–527. 10.1002/cnm.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Sundareswaran, K. S. , Haggerty, C. M. , de Zélicourt, D. , Dasi, L. P. , Pekkan, K. , Frakes, D. H. , Powell, A. J. , Kanter, K. R. , Fogel, M. A. , and Yoganathan, A. P. , 2012, “ Visualization of Flow Structures in Fontan Patients Using 3-Dimensional Phase Contrast Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 143(5), pp. 1108–1116. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Haggerty, C. M. , Restrepo, M. , Tang, E. , de Zélicourt, D. A. , Sundareswaran, K. S. , Mirabella, L. , Bethel, J. , Whitehead, K. K. , Fogel, M. A. , and Yoganathan, A. P. , 2014, “ Fontan Hemodynamics From 100 Patient-Specific Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Studies: A Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 148(4), pp. 1481–1489. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.11.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Zellers, T. M. , Driscoll, D. J. , Mottram, C. D. , Puga, F. J. , Schaff, H. V. , and Danielson, G. K. , 1989, “ Exercise Tolerance and Cardiorespiratory Response to Exercise Before and After the Fontan Operation,” Mayo Clin. Proc., 64(12), pp. 1489–1497. 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)65704-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Tang, E. , Wei, Z. A. , Whitehead, K. K. , Khiabani, R. H. , Restrepo, M. , Mirabella, L. , Bethel, J. , Paridon, S. M. , Marino, B. S. , Fogel, M. A. , and Yoganathan, A. P. , 2017, “ Effect of Fontan Geometry on Exercise Haemodynamics and Its Potential Implications,” Heart, 103(22), pp. 1806–1812. 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Banks, L. , Rosenthal, S. , Manlhiot, C. , Fan, C. S. , McKillop, A. , Longmuir, P. E. , and McCrindle, B. W. , 2017, “ Exercise Capacity and Self-Efficacy Are Associated With Moderate-to-Vigorous Intensity Physical Activity in Children With Congenital Heart Disease,” Pediatr. Cardiol., 38(6), pp. 1206–1214. 10.1007/s00246-017-1645-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Troutman, W. B. , Barstow, T. J. , Galindo, A. J. , and Cooper, D. M. , 1998, “ Abnormal Dynamic Cardiorespiratory Responses to Exercise in Pediatric Patients After Fontan Procedure,” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 31(3), pp. 668–673. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00545-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Ciliberti, P. , Schulze-Neick, I. , and Giardini, A. , 2012, “ Modulation of Pulmonary Vascular Resistance as a Target for Therapeutic Interventions in Fontan Patients: Focus on Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors,” Future Cardiol., 8(2), pp. 271–284. 10.2217/fca.12.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Cunningham, J. W. , Nathan, A. S. , Rhodes, J. , Shafer, K. , Landzberg, M. J. , and Opotowsky, A. R. , 2017, “ Decline in Peak Oxygen Consumption Over Time Predicts Death or Transplantation in Adults With a Fontan Circulation,” Am. Heart J., 189, pp. 184–192. 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Latus, H. , Lederle, A. , Khalil, M. , Kerst, G. , Schranz, D. , and Apitz, C. , 2019, “ Evaluation of Pulmonary Endothelial Function in Fontan Patients,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 158(2), pp. 523–531.e1. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.11.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Henaine, R. , Vergnat, M. , Bacha, E. A. , Baudet, B. , Lambert, V. , Belli, E. , and Serraf, A. , 2013, “ Effects of Lack of Pulsatility on Pulmonary Endothelial Function in the Fontan Circulation,” J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg., 146(3), pp. 522–529. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Pike, N. A. , Vricella, L. A. , Feinstein, J. A. , Black, M. D. , and Reitz, B. A. , 2004, “ Regression of Severe Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations After Fontan Revision and “Hepatic Factor” Rerouting,” Ann. Thorac. Surg., 78(2), pp. 697–699. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Wu, I. H. , and Nguyen, K. H. , 2006, “ Redirection of Hepatic Drainage for Treatment of Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations Following the Fontan Procedure,” Pediatr. Cardiol., 27(4), pp. 519–522. 10.1007/s00246-006-1261-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Kutty, S. , Rathod, R. H. , Danford, D. A. , and Celermajer, D. S. , 2016, “ Role of Imaging in the Evaluation of Single Ventricle With the Fontan Palliation,” Heart, 102(3), pp. 174–183. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Jarvis, K. , Schnell, S. , Barker, A. J. , Garcia, J. , Lorenz, R. , Rose, M. , Chowdhary, V. , Carr, J. , Robinson, J. D. , Rigsby, C. K. , and Markl, M. , 2016, “ Evaluation of Blood Flow Distribution Asymmetry and Vascular Geometry in Patients With Fontan Circulation Using 4-D Flow MRI,” Pediatr. Radiol., 46(11), pp. 1507–1519. 10.1007/s00247-016-3654-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Rutkowski, D. R. , Barton, G. , François, C. J. , Bartlett, H. L. , Anagnostopoulos, P. V. , and Roldán-Alzate, A. , 2019, “ Analysis of Cavopulmonary and Cardiac Flow Characteristics in Fontan Patients: Comparison With Healthy Volunteers,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 49(6), pp. 1786–1799. 10.1002/jmri.26583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Tree, M. , Wei, Z. A. , Trusty, P. M. , Raghav, V. , Fogel, M. , Maher, K. , and Yoganathan, A. , 2018, “ Using a Novel In Vitro Fontan Model and Condition-Specific Real-Time MRI Data to Examine Hemodynamic Effects of Respiration and Exercise,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 46(1), pp. 135–147. 10.1007/s10439-017-1943-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Medero, R. , Hoffman, C. , and Roldán-Alzate, A. , 2018, “ Comparison of 4D Flow MRI and Particle Image Velocimetry Using an In Vitro Carotid Bifurcation Model,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 46(12), pp. 2112–2122. 10.1007/s10439-018-02109-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Ferré, J. C. , Bannier, E. , Raoult, H. , Mineur, G. , Carsin-Nicol, B. , and Gauvrit, J. Y. , 2013, “ Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) Perfusion: Techniques and Clinical Use,” Diagn. Interv. Imaging, 94(12), pp. 1211–1223. 10.1016/j.diii.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Petcharunpaisan, S. , Ramalho, J. , and Castillo, M. , 2010, “ Arterial Spin Labeling in Neuroimaging,” World J. Radiol., 2(10), pp. 384–398. 10.4329/wjr.v2.i10.384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Wu, H. , Block, W. F. , Turski, P. A. , Mistretta, C. A. , Rusinak, D. J. , Wu, Y. , and Johnson, K. M. , 2014, “ Noncontrast Dynamic 3D Intracranial MR Angiography Using Pseudo-Continuous Arterial Spin Labeling (PCASL) and Accelerated 3D Radial Acquisition,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 39(5), pp. 1320–1326. 10.1002/jmri.24279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Johnson, K. M. , Lum, D. P. , Turski, P. A. , Block, W. F. , Mistretta, C. A. , and Wieben, O. , 2008, “ Improved 3D Phase Contrast MRI With Off-Resonance Corrected Dual Echo VIPR,” Magn. Reson. Med., 60(6), pp. 1329–1336. 10.1002/mrm.21763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Pedersen, E. M. , Stenbøg, E. V. , Fründ, T. , Houlind, K. , Kromann, O. , Sørensen, K. E. , Emmertsen, K. , and Hjortdal, V. E. , 2002, “ Flow During Exercise in the Total Cavopulmonary Connection Measured by Magnetic Resonance Velocity Mapping,” Heart, 87(6), pp. 554–558. 10.1136/heart.87.6.554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. He, X. , and Ku, D. N. , 1996, “ Pulsatile Flow in the Human Left Coronary Artery Bifurcation: Average Conditions,” ASME J. Biomech. Eng., 118(1), pp. 74–82. 10.1115/1.2795948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Rutkowski, D. R. , Medero, R. , Garcia, F. J. , and Roldán-Alzate, A. , 2019, “ MRI-Based Modeling of Spleno-Mesenteric Confluence Flow,” J. Biomech., 88, pp. 95–103. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]