Abstract

Purpose: Lack of appreciation of cultural differences may compromise care for seriously ill minority patients, yet culturally appropriate models of palliative care (PC) are not currently available in the United States. Rural patients with life-limiting illness are at high risk of not receiving PC. Developing a PC model that considers the cultural preferences of rural African Americans (AAs) and White (W) citizens is crucial. The goal of this study was to develop and determine the feasibility of implementing a culturally based PC tele-consult program for rural Southern AA and W elders with serious illness and their families, and assess its acceptability to patients, their family members, and clinicians.

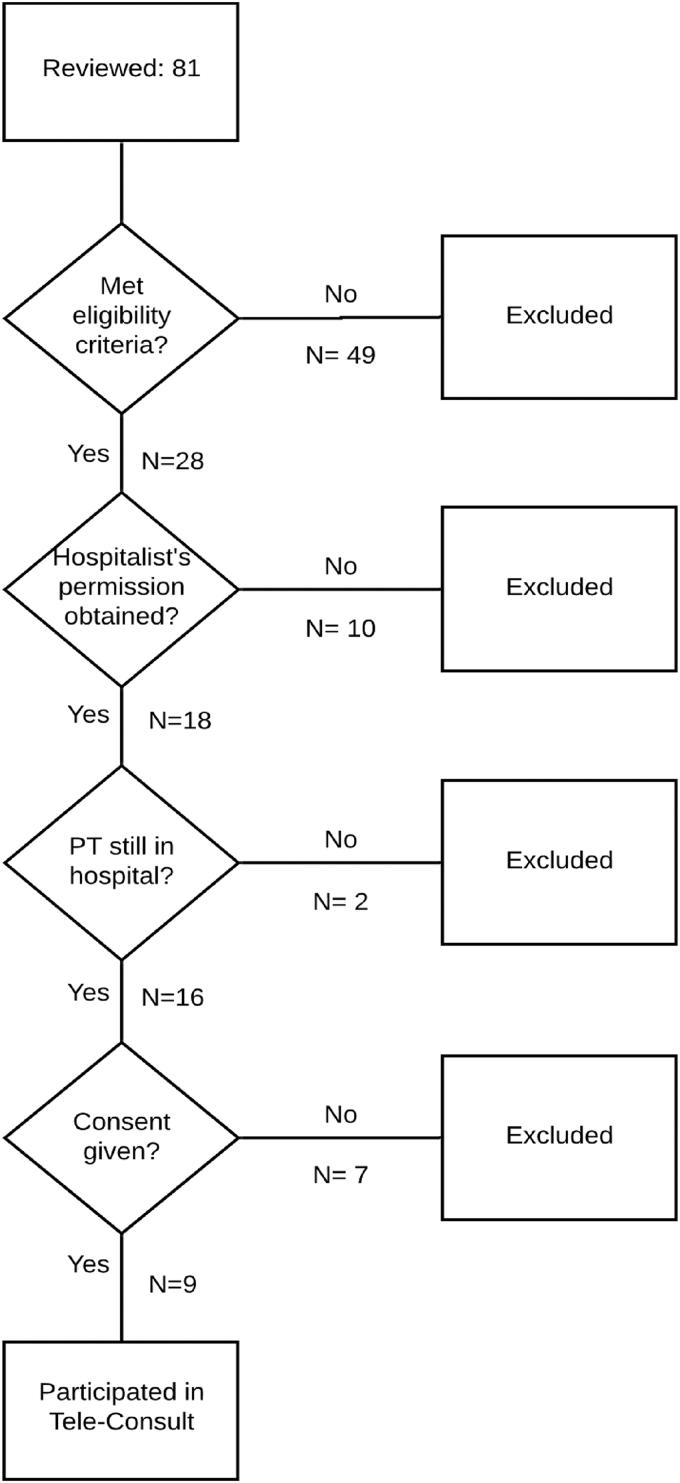

Methods: This was a three-phase study conducted in rural Beaufort, South Carolina, from January 2013 to February 2016. We used Community-Based Participatory Research methods, including a Community Advisory Group (CAG) with equal numbers of AA and W members, to guide the study. Phase 1: Cultural values and preferences were determined through ethnic-based focus groups comprising family members (15 W and 16 AA) who had cared for a loved one who died within the past year. We conducted a thematic analysis of focus group transcripts, focused on cultural values and preferences, which was used as the basis for the study protocol. Phase 2: Protocol Development: We created a protocol team of eight CAG members, two researchers, two hospital staff members, and a PC physician. The PC physician explained the standard clinical guidelines for conducting PC consults, and CAG members proposed culturally appropriate programmatic recommendations for their ethnic group for each theme. All recommendations were incorporated into an ethnic-group specific protocol. Phase 3: The culturally based PC protocol was implemented by the PC physician via telehealth in the local hospital. We enrolled patients age ≥65 with a life-limiting illness who had a family caregiver referred by a hospitalist to receive the PC consult. To assess feasibility of program delivery, including its acceptability to patients, caregivers, and hospital staff, using Donebedian's Structure-Process-Outcome model, we measured patient/caregiver satisfaction with the culturally based consult by using an adaptation of FAMCARE-2.

Results: Phase 1: Themes between W and AA were (1) equivalent: for example, disrespectful treatment of patients and family by hospital physicians; (2) similar but with variation: for example, although religion and church were important to both groups, and pastors in both ethnic groups helped family face the reality of end of life, AA considered the church unreservedly central to every aspect of life; (3) divergent, for example, AAs strongly believed that hope and miracles were always a possibility and that God was the decider, a theme not present in the W group. Phase 2: We incorporated ethnic group-specific recommendations for the culturally based PC consult into the standard PC consult. Phase 3: We tested feasibility and acceptability of the ethnically specific PC consult on 18 of 32 eligible patients. The telehealth system worked well. PC MD implementation fidelity was 98%. Most patients were non-verbal and could not rate satisfaction with consult; however, caregivers were satisfied or very satisfied. Hospital leadership supported program implementation, but hospitalists only referred 18 out of 28 eligible patients.

Conclusions: The first culturally based PC consult program in the United States was developed in partnership with AA and W Southern rural community members. This program was feasible to implement in a small rural hospital but low referral by hospitalists was the major obstacle. Program effectiveness is currently being tested in a randomized clinical trial in three southern, rural states in partnership with hospitalists. This method can serve as a model that can be replicated and adapted to other settings and with other ethnic groups.

Keywords: culture, palliative care, CBPR (community-based participatory research), rural, African American, telehealth

Introduction

Culture fundamentally shapes how individuals make meaning out of illness, suffering, and dying,1 and it strongly influences people's responses to diagnosis, illness, and treatment preferences.1–3 Considering patients' and families' culture is essential in all aspects of palliative care (PC). A lack of sensitivity to cultural differences may compromise end-of-life care for minority patients.4 However, culturally appropriate models of care that consider the diverse cultural preferences of seriously ill rural patients and their family caregivers are not currently available in the United States. There is an urgent need for research that emphasizes varying end-of-life care cultural preferences.4–10

The triple threat of rural geography, racial inequities, and older age hinders access to high-quality PC for rural Americans. In a state-by-state report card,11,12 the Southeastern United States, where a there is a significant proportion of rural dwellers and African Americans (AAs), PC access was ranked the lowest in the nation. Rural patients with life-limiting illness are at high risk of not receiving appropriate care due to a lack of health professionals (nearly two-thirds of rural U. S. counties are designated health professional shortage areas),13 long distances to treatment centers,14 and limited PC clinical expertise.15 Seventy-five percent of South Carolina (SC) is rural, and 34% of its residents reside in rural areas,16 where poverty and unemployment rates are high and per capita income is low.17 AAs comprise 36% of those who live in rural SC.18

The lack of PC services in rural settings is evident in the lack of guidance by national organizations to address the unique challenges and barriers faced by rural patients.19 The clinical guidelines on quality PC from the National Consensus Project20 did not contain the term “rural” through the first three editions, nor did they address how these standards should be applied in rural settings.21 Geographic inequities in access to PC are expected to rise as the rural population ages and the demand for PC increases.22 Rural patients with life-limiting illness remain vulnerable and at high risk of not receiving appropriate care. During the past few months of life, rural patients may experience significant and unnecessary suffering that an accessible PC consult could have alleviated; this is a major disparity for seriously ill rural patients.7 The need for research to guide best practices in providing PC to rural patients is pressing.21

Even when palliative and hospice services are available, AAs, when compared with Whites, are more likely to receive medically ineffective, poor quality, and high-cost care, due to general mistrust of health care providers and a fragmented health care system that is generally insensitive to cultural differences that can guide treatment choices.23–28 Despite proven effectiveness, numerous studies have shown that AAs underutilize palliative and hospice care.29–34 Suggested reasons for this include both a lack of exposure to hospice or PC information35–37 and possibly differences in values for end-of-life care.

Historically, end-of-life care has been rooted in White middle class cultural and religious values,4,36 with its very different frame of reference, value system, and life experience compared with many AAs.38 Where middle class Whites may emphasize individual choice, AA values support family-centered decision making.7 Faith, spiritual beliefs, and guidance of a spiritual leader36 are very meaningful to AAs, especially as they cope with illness and make treatment decisions.39,40 However, physicians rarely ask patients about their spirituality.41 AAs rely on hope42 and faith in God's healing power:43 This can be at odds with physicians' felt need to share a terminal prognosis.31

Inpatient PC consultations have identified unrecognized symptoms and unmet needs,44–48 and they have been associated with fewer intensive care unit (ICU) days49,50 and ICU deaths,51 and improved care processes and higher rates of documentation of goals of care.29,30,52 However, lack of access to palliative consultations results in less availability of PC benefits to rural and minority patients.

Finally, and most significantly, historical and social factors, including slavery, racism, medical experimentation and exploitation,31,53 as well as ongoing racism and microaggressions,54 have left a deep-seated legacy of mistrust in the AA community.55–57 A recent report58 found that AAs and Whites were “worlds apart” in their perceptions of racial equality and actual gaps in household income. This is even more strongly felt in the “Deep South” where slavery was promoted.59 A recent study60 found that AAs are more likely than other racial groups to believe that physicians did not care about them as individuals, and were less likely to trust their physicians' judgment and personal competence.

The overall goal of this three-phase study was to develop and determine the feasibility of implementing a culturally based PC tele-consult program for rural Southern AAs and White elders with serious illness and their families, and assess its acceptability to patients, their family members, and clinicians. The aims by phase were: Phase 1: To determine cultural values and preferences of each ethnic group and ascertain ethnic group commonalities and differences. Phase 2: To develop a culturally based PC consult protocol across ethnic groups. Phase 3: To determine feasibility of program delivery, and acceptability to patients, caregivers, and clinicians, and patient/caregiver satisfaction with the culturally based consult.

Methods

The study was conducted at Beaufort Memorial Hospital (BMH) in Beaufort, SC. Beaufort County has a population of 175,852, and most of Beaufort County's census tracts are rural.61 IRB approval for all three phases of the study was obtained from the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board, and for Phase 3, from the Beaufort Memorial Hospital.

Study design

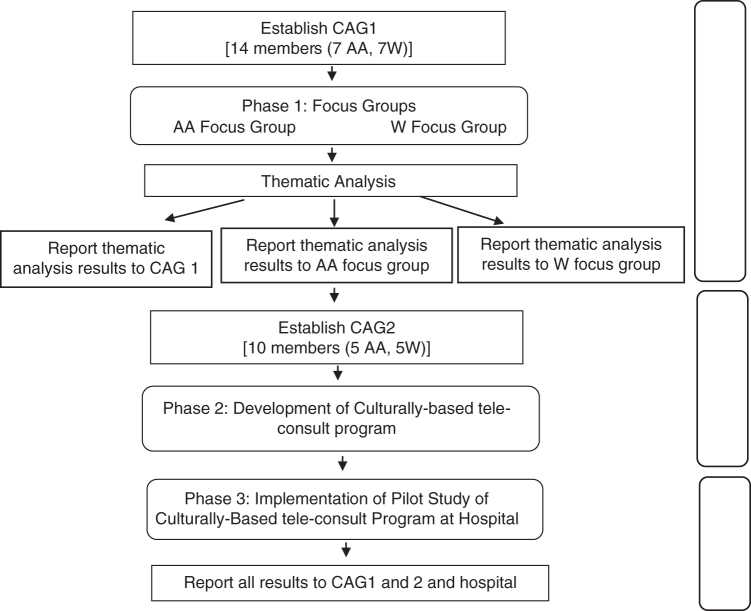

This three-phase study used Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) methods and principles, as illustrated in Figure 1, to define the study protocol and identify feasibility of a culturally based PC consultation to improve PC access. CBPR, a public health method in which academia and the community form a joint partnership to address community issues, has been found to address health disparities62,63 and result in demonstrable positive health outcomes.64

FIG. 1.

Study design.

CBPR builds on community strengths; the community is integral to all phases of the research, for the mutual benefit of all partners involved in the process, and in disseminating findings and knowledge to all partners.65 Consumer input has been demonstrated to enhance both the quality and acceptability of interventions. CBPR has been recommended as a promising strategy for PC research that aligns with the priorities of stakeholders, as a means to deliver tailored and appropriate care to underserved communities.66

Phase 1 engaged community members in the planning phase, serving as the first step in forming relationships and building trust with the community, and in obtaining community guidance into the study. Community Advisory Group (CAG) members were recruited with the assistance of the community health educator at BMH who had strong ties with community groups.

The CAG included equal numbers of AA (n=7) and White (n=7) members. The AA members were a county council member, leader of the Gullah Church Nurses Association, a pastor of a local AA church, a hospital employee, a hospice social worker, and a community member whose wife had recently died. White members included the nursing director of the BMH Cancer Center, its community health educator, a local social worker, two local hospice staff, and a community member whose loved one had recently died.

Phase 1: CAG planning and focus groups

The CAG planning meetings for Phase 1 (1.5 h each) were held over 2 months at BMH. The CAG members received an honorarium for their time ($25/meeting) and a gas card ($25/meeting) for travel.

Focus groups

In designing the research protocol, we chose focus groups as the most appropriate data gathering method for the study, as past research has suggested they provide an atmosphere that is the most conducive to respondents in sharing their personal experiences.67–69 We presented our rationale for this decision and elicited CAG feedback as to the appropriateness. CAG members were familiar with focus groups; this method had been widely used in Beaufort in an assessment of health care needs,70 and considered this method appropriate. The CAG members provided input into culturally appropriate ways to recruit for, plan, and run the focus groups. The AA members strongly recommended holding separate focus groups by ethnicity, making it clear that AAs would be more comfortable and more likely to speak openly if focus groups were limited to AAs. As a result, we revised the original consent forms to hold separate focus groups.

CAG members designed the recruitment flyer, using a design that was considered appropriate for each community, and distributed these to churches, hospitals, hospices, and other community settings. Local newspapers were sent information, and the principal investigator (PI) and CAG members were interviewed for three articles published. The CAG-developed screening protocol was used to determine eligibility of potential callers. The CAG members recommended that focus groups be held in a well-respected but neutral space. Meeting dates and times were weekdays after 5:00 pm, lasting no more than an hour and a half, and included a light dinner.

Focus group inclusion criteria

To be eligible to participate in the focus group, respondents had to be a family member of a loved one aged 60 and older who had died in the previous 12 months after an illness of 3 or more months, and in whose care they had been involved. Both the family member and loved one had to be Beaufort County residents, and the loved one had to have been treated in Beaufort County (with the possibility of occasional visits to larger hospitals in Charleston or Savannah). Thirty-one focus group members were recruited (15 White and 16 AA) (Table 1). Two thirds were immediate family; all provided at least 3 h of care/day to their loved one, with half providing 12 or more h of care per day.

Table 1.

Phase 1: Demographics of Focus Group Participants

| White, n (%) | AA, n (%) | Total | Percent of sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated in study | 15 | 16 | 31 | 100 |

| Years in Beaufort County | ||||

| <5 | 0 (0) | 2 (12.5) | 2 | 6.45 |

| 5–15 | 7 (46.6) | 1 (6.25) | 8 | 25.81 |

| 16–25 | 4 (26.6) | 2 (12.5) | 6 | 19.35 |

| >25 | 4 (26.6) | 11 (68.75) | 15 | 48.39 |

| Relationship to loved onea | ||||

| Immediate family | 14 (93.3) | 10 (62.5) | 24 | 77.4 |

| Friends and extended family | 1 (6.67) | 6 (37.5) | 7 | 22.5 |

| Hours cared for loved one per day | ||||

| 3 | 3 (20) | 3 (18.75) | 6 | 19.35 |

| 4–8 | 3 (20) | 3 (18.75) | 6 | 19.35 |

| 8–12 | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.25) | 2 | 6.45 |

| 12 or more | 8 (53.33) | 9 (56.25) | 17 | 54.84 |

| Location of passing | ||||

| Hospital | 3 (20) | 2 (12.5) | 5 | 16.13 |

| Home | 8 (53.33) | 12 (75) | 20 | 64.52 |

| Nursing home | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | 3 | 9.68 |

| Hospice facility | 1 (6.67) | 2 (12.5) | 3 | 9.68 |

χ2(1, N=31)=4.21, p=0.040.

AA, African American.

Focus group guidelines

Focus groups were conducted separately by ethnic group. Facilitators were of the same ethnicity as the group they facilitated, consistent with focus group methodology and as has been used successfully elsewhere.71 Planning meetings to develop the guidelines for the focus groups were held with the PI, two co-investigators (Co-Is), and the two facilitators. Both facilitators (one faculty member and one doctoral student) had received training in conducting focus groups. The protocol included ground rules (e.g., confidentiality), an explanation of why focus groups were being held separately, and the questions (and their probes) posed to focus group participants over the two meetings.

Questions were designed to focus on topics that impact end-of-life care. In this article, we focus on family members' preferences toward the care their loved one received in the 12 months before their death. Questions on this topic included: (1) “What did you find to be particularly helpful about the care or treatment your loved one received during their end-of-life care?” (2) “What did you like or not like about the way the healthcare staff communicated with your loved one/the family?” (3) “During the course of your loved one's illness, whose advice did you seek or who helped in making decisions about your loved one?” and (4) “During the end-of-life care experience with your loved one, whom among the healthcare staff did you trust?”

Focus group meetings

Two focus groups, a week apart, were held for each ethnic group at the local University in a comfortable meeting room. A light dinner was provided. The community health educator greeted each participant and introduced the PI and focus group facilitator. Respondents were presented with two IRB-approved study consent forms: the first to participate in the focus group study, and the second to be contacted for follow-up and potential participation in the next phase of the study. The facilitator started the meeting by introducing herself, the note takers, and the social worker who remained outside the room during all focus group meetings in case a participant(s) required professional support, and the two note takers sat at the back of the room.

Notes and tape recorders were transferred for storage in a locked, coded box to a locked data-storage room at the University. All tapes were transferred to Verbal Ink, a transcription firm. All transcriptions were kept on secured computers accessible only to the PI and study coordinator. All questionnaires were kept in locked university storage, with a unique identifier assigned to each questionnaire.

Data analysis

Analysis of the data followed standard procedures for qualitative data analysis;72,73 that is, systematic thematic analysis of transcripts identifying major and minor thematic areas; coding categories using open, axial, and selective coding; and sorting the data into coded categories, construct, and name typologies to describe family members' preferences for end-of-life care.67,68,73 A theme was defined as an issue raised or discussed by at least two or more members in that focus group. Themes were identified for coding based on the repetition of specific words, phrases and opinions, use of language and general thought patterns, as well as specific topics that dominated the focus group discussion.

Coding was conducted separately for each focus group meeting by two independent raters (R.E. and S.L.). Each independently reviewed and coded the data for themes, and then identified agreement. This was repeated for each of the four focus group meetings. In cases where there was no agreement, a discussion was held between the two raters and a Co-I (S.L.) experienced in focus group analysis, to reach consensus. Each agreed-upon theme and sub-theme was clearly defined, and several illustrative quotes were provided. Each theme was examined to determine whether it was similar across the two groups or whether it varied by group, and if so, in what way.

Report to CAG

After completion of the thematic analysis, results of each focus group were presented back separately to each of the focus groups, and all results were reported to CAG.

Phase 2: CAG planning and development of culturally based PC tele-consult

Expansion of CAG

To expand community input and to compensate for some CAG member withdrawal, the CAG was expanded to include six additional members, three from each of the focus groups (CAG2). Focus group members added were selected among participants who had agreed to be re-contacted, had participated fully in the focus group meetings, and who held varying perspectives and opinions on a range of topics.

CAG2 met monthly for 28 months with the research team, which included the study PI (R.E.), the PC physician (J.H.) who participated remotely via Go-To-Meeting, and the study coordinator. Meetings were held on a Thursday evening at BMH, and a light dinner was provided. The CAG2 members received the same reimbursement as in Phase 1.

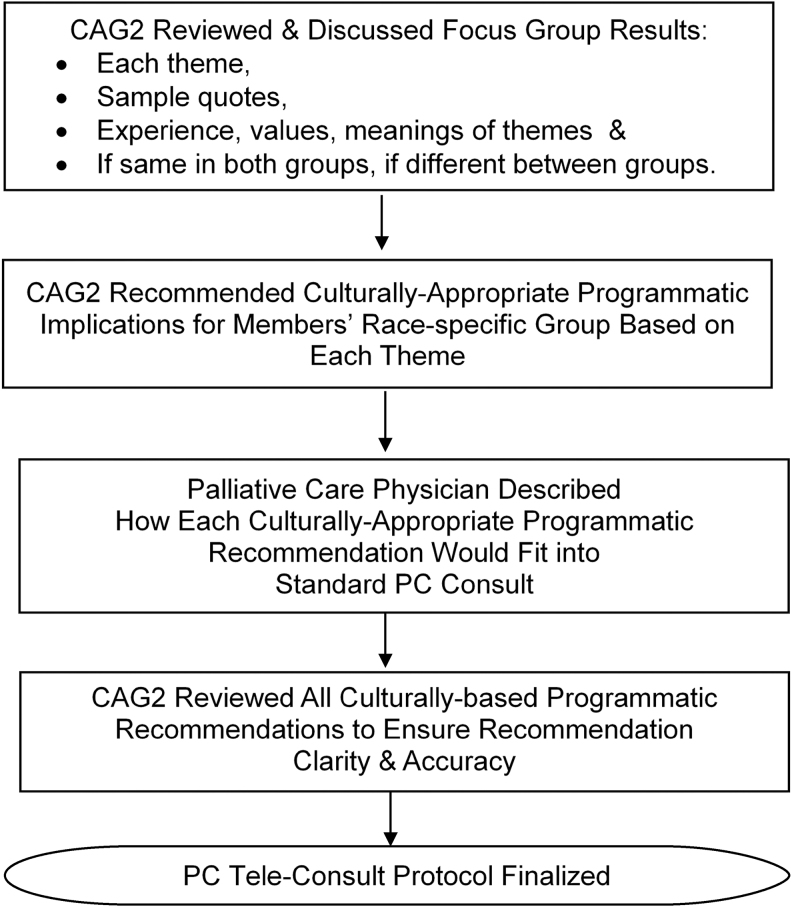

Figure 2 illustrates the process used in developing the culturally based tele-consult. (1) First, the PC physician described the elements of a Standard Palliative Care Consult20 to provide an overview of where the community recommendations would fit. (2) The CAG2 reviewed each of the Phase 1 themes, including sample quotes that illustrated each them. Following an overview of all the themes, each theme was reviewed and discussed individually. (3) For each theme, and for their ethnic group, CAG2 members recommended culturally appropriate programmatic recommendations for the culturally based PC consult that they were designing. If the theme applied to both groups equally, all members made these recommendations, and if it was applicable to one or other group only, members of that group made the recommendations. (4) All the recommendations were reviewed to ensure an accurate portrayal of what CAG2 recommended, and those that did, were written into a study protocol for the study team and the PC physician to adhere to. The group discussed those that were not accurately portrayed further, until the representation was accurate.

FIG. 2.

Phase 2 developing the culturally based PC tele-consult program. PC, palliative care.

Phase 3: CAG planning and implementation of the pilot study culturally based PC tele-consult

Few, if any, research studies take place in such small rural hospitals and a hospital “gatekeeper,” the Chief Nursing Officer, opened several doors to approach the hospital CEO. Approval was obtained from the hospital CEO, and after a formal presentation to their IRB, approval for this study was given. Presentations were made at hospitalists' meetings by the PC physician and the study PI on at least two occasions to explain the study aims and methods. Cards with eligibility criteria were created and handed out to all hospitalists. The Study Coordinator was present at the hospital every day and built relationships with floor nurses, to whom she explained the study and gave out eligibility cards.

Eligible patients were only approached after permission from the hospitalists was obtained by means of an order for a PC consult from the hospitalist. Based on CAG recommendations, CAG members were the first to meet the patient and family members to explain the study to them. If there was interest in the study, CAG members introduced the study coordinator who completed the consent process.

All PC tele-consults were conducted in the patient's hospital room at a time convenient to the patient and family members. The telehealth computer was brought in by the study coordinator who remained in the room with the family during the consult. After the consult, the PC physician charted his findings and recommendations, which hospitalists could review. The study coordinator alerted the hospitalist that the report was in the chart, and it was the hospitalists' decision whether to implement PC physician's additional recommendations if any were made.

Midway through Phase 3, to enhance hospitalists' referral and involvement, we implemented a system whereby the PC physician texted the hospitalist by using a secure health care communication method, after the consult and offered to discuss the consult by phone if the hospitalist wished.

Feasibility of program delivery, including its acceptability to patients, caregivers, and hospital staff, was assessed by using Donebedian's Structure-Process-Outcome model.74 In this model, Structure examines the capacity of the care system (i.e., support of hospital staff and leadership, audiovisual equipment to access PC), Process evaluation addresses implementation fidelity to culturally based protocol, and Outcome evaluates acceptability of the program to patients and family and the effects of program on perceived patient and family satisfaction with the PC Consult (primary outcomes). Variables derived from this framework were measured through process evaluations (structure and process) and adaptation of FAMCARE-2 questionnaire (outcomes).

Results

Phase 1: focus groups

Calls to study hotline to participate in focus groups

Eighty-nine calls were received. Referral sources varied significantly between the two ethnic groups; the majority of Whites read about the study through articles in one of two local newspapers. Less than half of AAs called as a result of this source; most were referred directly by CAG members or through flyers placed in local churches by the CAG.

Exclusion

Eleven White callers and one AA did not meet eligibility criteria for focus group participation (primarily because their loved one had been treated in other parts of the United States).

Recruitment to focus groups

Due to higher than expected interest, we expanded our focus group numbers beyond our initially planned for 10 per group, and closed participation after consent was obtained from 15 Whites and 17 AAs.

Attendance at focus groups

All Whites (n=15) and all but one AA (n=16) who met eligibility criteria attended focus groups. There was considerable participation in both groups from all participants. Although a range of powerful emotions were shared, no one required the services of the social worker. Identifying data are presented in Table 1.

Relationships to loved ones varied significantly between the two groups. Most loved ones who had passed away in both groups were either parents or spouses, but there were more non-immediate family and friends in the AA group (i.e., great uncle, second cousin, godfather, and two close friends), supporting prior studies that document extended family members and fictive kin (unrelated by birth or marriage but with a significant relationship with the person, that are like a family member), as important members of AA families.75–77

Thematic analysis of focus group data

Ten themes, each with one or more sub-themes, emerged from the focus group data, and fell into two broad categories: (1) Experiences that patients and family members had at various treatment centers (physician offices, hospitals, hospices, nursing homes) during the care of their loved ones; for example, physician communication, pain medication; and (2) Cultural values, beliefs, and preferences; for example, the role of religion and church, family caregiving, cultural aspects of discussing death, and discussing prognosis.

Comparison of Themes Between Ethnic Groups: In eight of the themes, there were differences between the two ethnic groups within the sub-themes; one theme arose only among AAs (lack of trust) and one theme among Whites only (physician lack of respect for patients/family). All themes are described next.

Phase 1 themes and Phase 2 recommendations

As the recommendations made by the CAG in Phase 2 are built/depend directly on the themes in Phase 1, we present the results of both phases by the themes given next (Tables 2–11).

Table 2.

Theme: Lack of Trust in the Health Care System

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Distrust of medical system and physicians | “… that death hospital. That's what I call the hospital in O [small town in South Carolina] the death hospital. If you wanna’ die, go there. You will die.” I just wish I would have known honestly, what my grandfather died of, just put it on the paper …. Was it some sort of medication that you guys gave him that called it, you know, the end?” |

X | Role of CAG

Role of Physician

|

Role of CAG

|

CAG, Community Advisory Group.

Table 3.

Theme: Discomfort with Telehealth

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Uncomfortable with telehealth | “I'm just speaking for me, but some of the older ones wouldn't like it because a lot of people don't use computers. Some people do and some people don, you know, so it would be sort of difficult for some of our older people who don't … who is not computer literate at the time ….” “And like you said with older people, especially African American, the computer is not there yet. And as far as Skype goes, I don't even like to Skype too much unless my hair's right.” |

“I'm a person who wants everything simple, right in front of me. That's [telehealth] is very foreign to me. Very foreign.” “… I guarantee that my husband would not have been comfortable with it. My husband was 15 years older than I am, and I do think that it is something of an age [issue].” |

|

|

| (B) It could work with these provisions OR under these conditions | “If it's an agency or someone you have a relationship with already, where there's an established record of you, but you may come into crisis which we always do during these final days, and if that's the case, then you can have someone to listen.” “I think the telecommunication … has its advantage to some degree because we have transplanted families everywhere … but it's also good for that person to have the opportunity to talk with whoever it is taking care of that family member.” |

“You know, I think it could be helpful … I think that the first meeting, two, three, should be certainly in person, should be with a medical professional that you trust, and that you have a good relationship with … But then after that I think to not have to take J. out of the house, that to me would be fabulous.” “… we talked last week about how impersonal some of the people felt their doctors were, and that's what I think people are reaching out for. They want somebody that, whether they do or not … acts like they care, so I think that would be a really big plus to do it but have your physician there with you.” |

|

|

Table 4.

Theme: Treat Family and Patient with Respect

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Experiences of physicians acting in an insensitive or rude manner | X | “It wasn't our regular doctor, this man comes out in the waiting room and there's our church members and … N's mother and his sister and daughters and everybody out there. The waiting room was full. He says, ‘Well,’ he said, “I don't know how he's lived this long and it'll be a miracle if he's here at Thanksgiving,” and this was the end of September. “His heart and lungs are just shot and it's just a miracle that he's still living.” “I was trying to get the doctor to understand our insurance, and he says, ‘You know, usually when I give a patient a prescription and they go get it and they pay their $2,000, but here I have one who comes in and wants it for nothing.’ So I went to the pharmacy, called the insurance agency, told them what I was up against and he fixed it all. I got the T [medication.] I went back and he saw the bag in my hand, the doctor, and he says, ‘well, these insurance companies give you a hard time, don't they?’ I said, ‘it wasn't the insurance company. You were rude! What gives them a right to behave like that when you're under so much stress anyway?’ ” |

(1) Although this theme did not arise in the AA group, the recommendations were that physicians should be courteous, and respectful of confidentiality. | (1) Physicians should never be rude, always be courteous. |

Table 5.

Theme: Religion, Church, and Pastor

| Sub-themes | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Religion is our source of comfort and the church is at the center of our lives | “My son in law is a minister, so he called … and I asked him to please pray for him [patient] over the phone. So I put the phone to his ear, and I put the speaker on so we could both hear, and he prayed, and when he finished, my husband said ‘Amen’ right along with him and that was the last word he ever said. After that prayer he never said another word.” “And so because you encounter things and people will question you as to how you go through it or how you handled it; because it really has nothing to do with you; it has to do with your faith … because it is rough. You know, because it's someone you love and even though we know what the Word says about it, you really hate to part with that person.” “She [sister] said, ‘I mean you're tired’ and she said, ‘You just go ahead with the Lord.’ And my dad opened his eyes, and my sisters and I were standing around the bed, and he opened his eyes and he turned around and looked at all of us. He took that last breath and just went right on to sleep.” |

X | (1) Religion is the source of all of comfort, a key value, and it's the perspective from which AAs view the world. Therefore, in all PC physician interactions with AA patients, recognize and respect that this is an integral part of all that is said and done. | X |

| (B) Pastor helped accept end-of-life reality | “And at Sabbath, they was in service at church and my pastor was there … and I just started screaming that afternoon. I mean just boo-hoo, crying like someone was killing me, and he came over to me and he prayed. And he said, ‘God said to tell you that you've done all that you can do. So you've done everything you could do for him.’ ” “Those last two weeks, I mean he just went down, and when I had—my daughter and son-in-law had gone to a football game and so—my son-in-law is a minister, so he called after they got back from the game and I asked him to please pray for him over the phone. So I put the phone to his ear, and I put the speaker on so we could both hear, and he prayed. And when he finished, my husband said ‘Amen’ right along with him, and that was the last word he said. And that was on a Friday night, and the following—not the next Saturday, but a week from that, is when he passed. But that was the last word he said—‘amen.’ After that prayer, he never said another word.” |

“I was in denial … and disconnected about it. But … that's when I got my pastor involved.” “But when our pastor came and stood in the doorway and said, ‘P. peace be with you,’ it had an impact.” |

(1) Pastors are the key to helping us understand prognosis and impending death. If the issues of prognosis arises, suggest that they may want to invite their pastors to the discussion of prognosis. Then ask the name of the pastor and say you would welcome them to the meeting. | (1) Pastors are the key to helping us understand prognosis and impending death. If the issues of prognosis arises, suggest that they may want to invite their pastors to the discussion of prognosis. Then ask the name of the pastor and say you would welcome them to the meeting. |

| (C) Church members as support | X | “My church family was absolutely my lifeline. They got me through everything because whatever N. went through, the church went through it, and it affected everybody in the church.” “I had a church family that was wonderful to me. They were absolutely wonderful to us.” |

X | (1) Church members are a source of support for patients and family members. If patient and/or family members need support, ask whether a church member can assist. Ask for name of the church member and discuss how they can provide support. |

PC, palliative care.

Table 6.

Theme: Discussing Death and Prognosis

| Sub-themes | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Death is not discussed | “And that was tough, because as a family unit we never discussed death. We never really sat around the dinner table and discussed death, and you know, really said, ‘well, this is what we're gonna’ do. We wanna’ make sure you're comfortable.’ … we just didn't talk about death, other than someone else's death.” “You know that [hospice] is the end of life, and I think that's because of our upbringing.” “As things progressed and he got more and more debilitated and weaker … and my concern was about him and did he have any fear about the end of his life. And so I never really did know how to approach him about it, but I just happened to be there one evening and we were talking, and he looked up at me and he said, ‘I'm not afraid to die,’ So when he said that to me, it gave me a calmness, a kind of peace within me.” |

X | (1) Death is not discussed in our church or at home. Recognize that and approach this topic (death, impending death, possibility of death) with caution. (See section on prognosis for how to discuss prognosis.) | X |

| (B) Sharing prognosis in a negative manner | X | “But the way we found out was a nightmare, and I don't wish that on anybody, especially with a room full of people.” “All of these privacy things that everybody's so concerned about, and yet, at the same time, we have the entire waiting room being informed about your husband's, you know [health information] … And then earlier this afternoon, you [moderator] mentioned something again about HIPAA. So it's just—it's very frustrating that that's such a big deal and you have to sign these papers and all that stuff, and yet, when it's not convenient to the doctor, then [they disregard those procedures.]” |

|

|

| (C) Positive experience in sharing of prognosis | “The doctor explained it to me that the body is shutting down. He said, ‘You don't need to make him take him to the hospital and feed him, because the body is shutting down.’ He said, ‘Don't let them give you whatever to bring him back,’ he said, ‘because he is so frail, when they go down to press on him, they're gonna break the ribs.’ ” “I think when a person is understanding, then they're more accepting as to what is about to happen, and I think with him—both of us, it was comforting to know that we had that conversation … and it prepared us for what was gonna come.” “But Saturday morning, we went to see him and the doctor—one of the on-call doctors came by and he was telling him what was going on and how the lungs had really—were so compromised, that there was just nothing else they could do. So he, in his usual way, what is the prognosis. They with the military background, you know, he was always that. So the doctor was very honest. He says that is up to someone much higher than me, and I admire him for saying that because really, like he said, how do they know” |

“The doctors were so caring and giving and hew was up one time and it was close to the end of life … and the doctors and the nurses were just crying with him and hugging him … just because he felt so bad and they were doing everything they could.” “The doctors at M hospital were wonderful. They told us, they confirmed that it was malignant, and then the doctor that was gonna’ do the surgery confirmed that it was very aggressive, but he said, ‘we can fight this together’ and he went on with encouragement … and the hope that you have to have… and they would get excited when we'd get a clear scan. So we all felt like it was a team effort and the doctor was working with us.” |

|

As in (E) Who to share prognosis with, and how to do it |

| (D) Clinician specifying time to death | “I'm gonna touch on my grandfather because on a Friday afternoon, about—and the sky looked about the way it is now, we received—we—my mom and my sister and myself—received a phone call at the house that I'm staying in now, and that phone call told us that my grandfather had two and a half days to live. And I never, ever understood how a doctor can tell you two and a half days to live.” “and the doctor told me that they gave him three weeks to live. My husband lived three years after that. After three weeks, the VA doctor came to my house, the social worker came to my house, …. They came to see how my house was and if I was able to take care of him. … and after they checked and see everything and they had me to perform some things and they see that I was capable, they send him home. He stayed home about two years.” |

X | X | X |

| (E) Who to share prognosis with, and how to do it | X | “I told the doctor, ‘don't tell her anything until you call me and tell me what the problem is.’ And when he did call and told me what it was, I says, ‘Please don't tell her. Let me tell her when she gets here,’ which would have been that day, but he did it anyways. So when they brought my mother to my house, she got out of the care, went straight to bed, and never got up again. And if he had listened to me that would not have happened. She gave up before she got here. So I really had some issues. It coulda’ been handled differently.” “My perspective is that … I had a good experience and I thought it was very loving, but the doctor saying it in front of the patient? Yes. Was that the right thing for my father? Yes. Would it be right for everyone? No, not necessarily.” |

X |

|

| (F) Miracles and hope | “As long as the patient is alive, there's always the possibility of a miracle.” “Only God knows when a person will die.” |

X |

|

X |

| (G) Bringing God into the sharing of prognosis | “So the doctor was very honest. He says ‘that is up to someone much higher than me.’ And I admire him for saying that because really, like he said, how do they know.” (God is the decision maker) “He had this wonderful doctor. All this man every talked about was God. That threw me off right there. I ain't never heard no doctor talking about God. Every time, you know, he's talking to me, he's saying something about God, and he said, ‘God got me her for this purpose, God got me here for this purpose, to make sure that he is well taken care of.’ And that is all he said.” |

X |

|

X |

Table 7.

Theme: Family Caregiving for Patient

| Sub-themes | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Take care of loved one at home | “And my sister, when she was in Florida and I was bring her home, she said, ‘Now, of anything happens to me, I don't want you to put me in no nursing home. Would you promise …?’ And I promise her. And I took her and she got worse and worse and worse. I took her just like a baby.” “I can remember the day that they released her from the hospital. Her main concern was not to go into a nursing home, and the family did abide by that, and I can remember that day. She'd kinda [leaned] me towards her and said, ‘I want you to go to home with me.’ And that's what I did. I was at her house between six and eight hours a day and once I week I would stay overnight.” “I think really what it boils down to is that you can't say we didn't take care of our loved one. We did. It's the way we was taught. We just take care of one another, so that's what we gotta come back to.” |

X |

|

X |

| (B) Take care of loved one at home no matter what the sacrifices | “It was my responsibility to take care of her. … the funny thing about it is that she got a hospital bed before she really got sick. I slept on an air mattress for 2 years. I own my own business so what happened is she would call me so I came up with the idea, that look, either I have to do my job or my wife, and I let the job go because I wanted to spend as much time as I could with her.” “So my uncle did not have to hear that [arguing about who will care for him]. Like oh, we—it's 6:00, where Jane at? I mean, I was Jane at 1:00, I was Jane at 3:00, I was Jane at 6:00, I was Jane at 8:00, I was Jane at 12:00, I was Jane at 1:00 in the morning. I was Jane. And I don't know, maybe I'm kinda on the crazy side. I didn't see that as a burden. I saw it as when I was a little girl, this man loved me. This man cared for me, and so it was my turn to give back. So he was not a burden to me.” “and I think it's taken us a while to get to where we allow other people to come into our homes and do that because we have always provided the care at all costs, and I don't think we realize that there are people that are trained to do that, so we don't have to be burdened—that we have our own family to get that care and we can take ourselves too. ‘Cause sometimes we're so busy caring for other people that we don't care of ourselves.” |

X |

|

X |

| (C) Guilt at having a loved one in the nursing home | X | “Well, I went through the guilt thing too because my dad ended up, the last eight months of his life, he was at {nursing facility.] We just couldn't handle him at home anymore.” “So the whole time he was there, we had to pay … we didn't have to, but we paid a private caregiver to go in from 9pm to 6am every day to be with my dad through the night because we knew he was not gonna’ get any attention whatsoever there during the night. I mean, he was, our know, piss poor during the day … excuse my French … but, you know. At least he had some attention during the day. … And it breaks my heart.” “My mother was pretty sick and had to have care all the time and she was terrified of going into a nursing home because she knew that she wouldn't be cared for, and so, you know we struggled with … what to do.” |

X |

|

Table 8.

Theme: Hospice and Nursing Homes

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus group |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Fears that hospice means death | “But when the hospice lady came, I would lock the gate. She called and I never let her in. She … called me on a Friday one day, she said, ‘I came to see G,’ I said, ‘Oh, we busy right now. I want you to come back in a few hours …. She said, ‘well, I'm here …’ I wouldn't let her. I just slammed the door. Yeah I did that for a long time.” “But we could never just say the word ‘hospice’ because hospice was death.” |

“Hospice was a huge decision for me because if you sign for hospice, then you have to give up some things, like daily physical therapy… and the wrestling of having to make that decision ‘cos he was clear of mind the entire time and in pain… I didn't want him to give up hope.” “He stopped eating, and that was a big chore trying to get him to eat, but I—when I was aware that hospice was—that he was eligible for hospice, I started grieving then.” |

See also section on Family Will Take Care of Loved One

|

|

| (B) Fears that hospice means taking change over the house | “It was like, well, maybe these people come in, talk about this man dying. I don't wanna’ hear this you know, so they don't come. That was my theory.” “Every time I look, there's a white person over this, there's a white person … look I gotta’ tell it like it is. Four of those people [from hospice] come to my house. All of them was Caucasian. Well, where are the black women? I find all of that … it really disturbed me. It really did. It got on my nerve.” |

X |

|

X |

| (C) Our community needs to be educated about hospice | “But I had been educated about [hospice], then I could have, you know, I could have made better choices, and I would have been a nice person …. And I did apologize to them.” “Hospice … that was at the end of life. And I think its because of our upbringing, and I think if there was a way that we could educate … by means of seminars, or going into churches or whatever. If we could educate about what all hospice has to offer, and not see hospice as ‘they're coming, okay, they're gonna die.’ ” |

X |

|

X |

| (D) Hospice support for patients | “And he was mouth open, everybody said they heard the death rattle … If he had a death rattle, I wouldn't have known. He wasn't eating anymore, and I said, ‘but he's hungry.’ She [hospice worker] said, ‘no, he's not hungry. He's not burning up no calories, not empty because he's not moving.’ She said. ‘And hospice, I love them.’ She said, ‘the body is shutting itself down,’ she said, ‘Mr. F. is not hungry.’ And I said, ‘but he ain't eating.’ She said, ‘mmm hmm.’ ” “So that's how hospice was …. I stand on the battlefield for them. They were just, … ‘what can I do?’ ‘what you need?’ ‘Do you need us to …’ Always treat you like you were the king of the hill like you were royal family. … I would never have enough to say about them ‘coz they played an important part in our lives. I told Mom, I said, ‘the minute anything happen to us, we going to hospice.’ ” |

“And without her [hospice worker] help, and the last time N was in the hospital in Intensive Care, she met me, came that night, helped … and N was wanting a fan. I mean she raised holy heck with this nurse that said you did not need a fan, and she made sure he got a fan because he was burning up. So I mean, you know, the care that with the social workers and the nurses, they were awesome. I can't commend them enough, and they have been wonderful to me.” “[Hospice worker] was awesome at that. She also had the ability to give P a foot rub that would just calm him right down, and sometimes it was the case where we were upping the medication but the medication hadn't had time to take effect, we needed someone who could work a little miracle and buy us some time, and [hospice worker, bless her dear heart, could do … [Hospice worker] was awesome at that.” |

(1) Those who received hospice care found it to be a source of support for patients. | (1) Those who received hospice care found it to be a source of support for patients. |

| (E) Hospice support for caregivers | “A lot of things were explained to me, and I thank God for that agency and the people who came into our lives were there, because if they weren't there, I wouldn't even know what to do. I wouldn't even know my head from my toes.” “They [hospice workers] wanna make sure not only the person that you're giving care to is being well taken care, but they want you to be well—and I don't know what it is, but seemed like you just—even the care with hospice people, seemed like you automatically became family. It wasn't like you were inviting some strange person that you never seen before when they come to your house, you know, like—it was none of that. They talked to my uncle like they knew him all his life. They talked to me, and I thanked God for hospice because if it was not for them, I wouldn't have a clue.” “But hospice—they helped—they was there for my mom, but it turned out, it ended up they were more there for me.” |

“And I can't say anything but just accolades for them because I could not have done it, and I knew when my—when A. (Hospice Worker) was there, I could walk outta the house and I did not have to worry one minute.” “And so, you know, as I said, all the people that came into our house, even other certified nursing assistants, I was very pleased with them because they listened to what I was telling them.” “We had a social worker come in and spend a lot of time with us and they called several times. We were very impressed with the hospice that were involved with us.” |

(1) Those who received hospice care found it to be a source of support for caregivers. | (1) Those who received hospice care found it to be a source of support for caregivers. |

| (F) Hospice care support by chaplain | X | “They were there every day, you know, and the chaplain stayed with me, and I did not need bereavement after. I mean, you know, it's very difficult, but they were there for me and I didn't need the bereavement group, but they had a memorial and I did go and they were so kind, even that night, to me and everybody else.” “The chaplain from the hospice that we, you know, he said he knew I wouldn't come … ‘cause she was taking … and he said you think she wants to talk to me. I said I will give her your number if she does. They reached out—they reached out to our family in New York for me, which …, but they did.” |

X | Those who received hospice care received support from chaplain. |

| (G) Hospice care support after death of loved one | X | “[I] was holding him when he died, and when they came to get him, she—the hospice nurse—took me into the dining room and said let's sit down and just—do you wanna pray. And I said yes, but she wouldn't let me watch.” “The hospice nurse was there. We were changing the sheets when my husband started to pass, so she left me alone with my husband. She called the funeral home, she made the arrangements to have him picked up, and she stayed after he left, and she got everything out of the house. There wasn't a bedpan, there wasn't a bedside commode, there wasn't bed rails. He never had a hospital bed. He went very quickly, but the shower chair was gone, just everything that reminded me when I walked in our bedroom of it being a sick room. She took—and most of it, you know, of course, was donated to the hospice to be used again.” “The morning that he passed away, I had so much family there, children, brothers, the house was packed full. Everybody was sleeping anywhere they could find to sleep, but when it happened, we were all numb. There was so much emotion going on, and the hospice nurse, the head one, took over everything. All we had to do was just sit there ‘cause we were numb. She took over the whole thing. Everybody was called, taken care of, she got everything out of the house, and she stayed. She was wonderful. That's a hard—I could not have done whatever needed to be done. I could not have done that.” |

X | (1) Those who received hospice care found it to be a source of support after the death of a loved one. |

pt, Patient.

Table 9.

Theme: Clarity About Opiate Dosage

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Lack of clarity about medication and medication regimen administration | “I could not understand why the medical field, they know a person is dying, yet they coming up with some kind of medication that they wanna' put in her mouth you know. So I told the head nurse, I said, ‘Well, why would you guys give here this medication and she's dying?’ She had stopped talking, she had stopped eating, all her body function was, you know, deteriorating okay, and this is what they told me, and I didn't like it at all. They told me that the medication that they was giving here was to ease her pain. I said, ‘she can't fell no pain. She's dying you know, and that's the problem. You know, that really got to me.’ ” “but that Tuesday, the nurse called in sick and they got a temporary nurse, and she gave him too much medicine ‘cause he told me that he was in la-la land. And then his daughter called and he told his daughter and his daughter called and got on the administrator of hospice and they came down and they apologized and that nurse that gave him too much medicine, they made her check on him every five minutes.” |

“The pain had gotten pretty bad with that pancreatic cancer, and the nurses and the medicine bottle told us how much to give, and they also specified, ‘just give this’ but they would come in to check on him, they would say, ‘well, you can give him more.’ We always got confused. Can we give him more, or do we have to follow what's on the bottle? And that was always an issue, even until the end, we never knew what the guidelines were on that.” “The doctor [would not give her pain medicine]; he was worried, that she was gonna’ get addicted, dependent, that's dangerous, You know, you have to tell the doctor, ‘look, the pain … give her the pain medicine … She's 96 years old … Please.’ ” |

X | (1) Explain what each medication is for in simple, easy to understand terms, especially the administration of morphine and its dosing. |

Table 10.

Theme: Advanced Care Planning

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Advanced care directive/DNR in writing | “We didn't have any words written out you know, we didn't have anything to really follow. It's interesting, it just happened. As a family, we are all accepting of … how that went.” “As a family unit, we just had to know in our hearts that this was the right thing to do, this is what he would have wanted. We didn't have an … Outline of what we needed to do next.” |

“We were in the ICU, he said, ‘This is the last time I'm coming to the hospital’. He said, ‘I will not come back’. And he signed the DNR. He told our social worker and the nurses, ‘You do not bring me back to the hospital. Everything is signed.’ He begged us not to let him die at the hospital … And whatever F. wanted, we put into place, and we did our best to have it. And he went out just like he wanted. He didn't wanna’ be resuscitated, no kind of life support, anything … And when he made the decision to stop dialysis, he know with his body like it was, the max he would have would be four days. And he made it three and a half.” “He had a DNR … but he was at home. Now nine days or so before he died, our hospice had just gotten a new doctor, and the new doctor wanted to talk about feeding tubes, and …. The hospice nurse was there, and she said, ‘No, that's not what he wants.’ But he [doctor] insisted on talking to T. and T. said, ‘That's not what I want.’ But the doctor wanted to consider it.” |

|

|

| (B) Confusion between advanced directives and power of attorney | X | “Well, I had gotten the advance directives from the hospital social worker, but … I probably didn't have a clear understanding. I always thought I had power of attorney because in the bank I had power of attorney, coz’ I could write, you know, whatever that was, but then when it came down to the insurance and all those other things, they were like, ‘you're not really power of attorney.’ ” “I had health care power of attorney, but I didn't know that that wasn't power of attorney until it was too late.” |

X |

|

ACP, Advanced Care Planning; AD, Advance Directive; DNR, do not resuscitate; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 11.

Theme: Need for Services

| Sub-theme(s) | Phase 1: focus groups |

Phase 2: recommendations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | White | AA | White | |

| (A) Need for specialized services for military personnel | “Now my husband … was a military man, and … very private person and it took a lot for anybody to come in and bathe him and change him. We would go to the VA hospital and they would always tell him, ‘okay, you served your country. You have earned the right to have home health, just home health care come in and help your wife’. My husband always said ‘no, we okay.’ And that's how the conversation went … I mean I took care of him for seven years, and then the last three years when he couldn't even walk anymore and we'd go back and forth to the hospital, ‘do you want care?’ ‘No, we okay. We fine.’ And this went on until April of this year, and then he allowed home health to come in couple days a week and they were able to, you know, bathe him. He accepted that. He saw—I think he saw that I was getting tired, and so he allowed them to come in and bathe him.” “My dad was a very strong man. My dad was a Marine. [The] mentality that they're very strong and, you know, they endure to the end and it was initially difficult for my dad to come to the—face the fact that we would be taking care of him ‘cause he's always taken care of us. I mean we are grown with children, grandchildren, my dad used to [take care of us]. And so it was really difficult for him to come to terms with us caring for him. And we just tried to impact upon him how fortunate we thought that we were ‘cause we were able to return some service at the end that he had given us.” |

“Being from a military background, we had—when we had an aide come in near the end, we had to say do not cover his feet, and then, of course, thankfully, they went with that.” “And again, if you have someone with a military background that has been in combat, they're going to, you know, maybe do things like, you know, I don't care how cold it was, there was at least one of … feet out at all times, but other little quirks or things that they learned and they listened. And for that reason, I was very comfortable.” |

(1) Understand someone who is from a military background. | (1) Understand someone who is from a military background. |

| (B) Need for specialized services for southern men | X | “My husband saw the chaplain from hospice and a priest, but my husband was a very southern man, and he was very internal. He didn't share feelings. You didn't do that when he was growing up, and you were a man in the south. You didn't cry, you didn't—not that he wasn't loving and caring with his family, but he wasn't going to burden anyone with his issues. And so, you know, they offered. They sent in social workers and—but, you know what I mean by southern man.” “The fact that his head RN had—was retired Naval petty officer, I'm here to tell you the man was not much taller than me, and I don't think he had an extra calorie on his body, and as I said to … one time, I said he was not serving in a hospital; he was out in combat… But there was a very close bond between him being the head RN and … you know, and I don't know how to explain that at all other than saying it was essentially one military, you know, sort of man with another.” |

X | X |

| (C) Need for financial assistance for those in financial need | “Low Country Council of Governments will give you up to $500 worth of stuff, so if you go home and see that you need to change your plugs to a three-prong plug-in outlet, they'll get a man to come in there and they'll pay for them, and that'll get your house set up, you know, okay so that you can live, but it's right here in the community, but it's just like no one really knows. No one tells anyone. So hopefully we can all find out and just let some people know.” “and then if you find out about it, you gotta go through so much. You got to have a certain income. You got the wait on this waiting list. You got to go through so much. It shouldn't be like that. Everybody should be to get this ___, you know. That's the way everybody want, to take care of their own.” |

“Well, nobody said … ‘you need to apply to Social Security for extra help.’ That's what it's called is extra help … And it would have been nice if I didn't have to spend three weeks, because I didn't know what I was doing. I was navigating blindly. Surely somebody out there knew… that this thing existed …” “I went to the Good Neighbor Clinic when … first got really, really sick because we could not afford some of his medications … But anyway, I swallowed my pride and I went to the Good Neighbor Clinic and I begged, borrowed and pleaded … and said ‘look, my husband is going to die if I don't get some help. And I mean you all are here to help us.’ … luckily I had a case worker there that helped me and she got on the computer and she filled out all the forms … and we ended up getting most of them for free, and then we got turned down on some.” |

(1) AA community do not ask and do not know what is available. There is a need for community members to be aware of community resources. | X |

Lack of trust in the health care system and in physicians was a theme in the AA group (Table 2). To build trust, CAG members suggested that they meet and greet AA patients and families first, introduce themselves, briefly describe the study and the consult, and explain that they were an integral part of the development of the protocol. Although the issue of lack of trust did not arise among White CAG members, they felt this would be beneficial for White patients too, and suggested they be the first to meet White patients and families.

To do this, CAG members had to become hospital volunteers and undergo volunteer training. All but one CAG members did so. The CAG also developed a colorful page about the study in which they used images of the ethnically diverse CAG working on the study, a photograph of the PC physician for this study, a computer with a person in a bed talking to a patient, and a simplified illustration of the data to be collected, which they would share with the patient and family.

Telehealth, the remote delivery of health care and sharing of medical knowledge using telecommunication, has been used to deliver health care to remote areas,78–84 and it was the method by which this consult was conducted primarily due to the health professionals' shortage (including PC services) in the rural South, together with large geographical distances in rural areas. Since this method was not widely used in local health care settings, we anticipated that community members might be unfamiliar with it. We therefore, raised the issue in the focus groups to hear how community members felt about it and what their suggestions were for a reduction in potential community concern. Recommendations made to overcome this discomfort were the same for both ethnic groups and included the PC physician wearing a white coat (to indicate that he/she is a physician), as well as the PC physician acknowledging the inability to be physically close to one another. They also requested that a family member be in the room, and, to ensure continuity of care between the tele-consult and hospitalists, that the study coordinator be present (Table 3).

A theme that arose in the White focus group was their experiences of physicians acting with a lack of sensitivity, outright rudeness, and/or not respecting confidentiality (Table 4). Although this was not raised by the AA patients, both ethnic groups strongly endorsed the recommendation that the PC physician conducting the consult would always treat the family and patient courteously, and never violate patient confidentiality.

Table 5 highlights a significant cultural value that impacts both ethnic groups, the role of religion and church in the lives of both ethnic groups. Although religion and church was important to both groups, in the AA group, religion was considered the source of all comfort, with the church serving as the center of all aspects of community and personal life. The pastor played a key role in helping family members accept the reality of the impending death in both groups. A difference occurred in terms of support: In the White group, it was the church members that provided support; whereas in the AA community, family was key (as seen in Table 7).

Table 6 highlights a core cultural value of the AA group, and that is that the family takes care of their loved one, regardless of the sacrifices it requires. “It's the way we was taught. We just take care of one another.” Sending a loved one to a nursing home was considered unacceptable among the AA group, and only one CAG member had a loved one in a nursing home, due to the patient having Alzheimer's and continually running away, requiring her to be in an enclosed environment. This has implications for the physician referring patients to home hospice or nursing homes (see also Table 8) where nurses or other professionals will come into the home.

Three themes about death and dying emerged in the AA focus group, all of which are tied to church teachings and doctrine. Death and impending death were not talked or preached about in church, and consequently, not discussed in community members' homes; the concept of maintaining hope, a fundamental aspect of faith, was reflected in names of AA churches, in pastoral messages, and in community songs, and the unshakeable belief that whatever happens to the patient is in God's hands.

Based on these concepts, the CAG asked physicians to understand these concepts, recognize them as important, approach the concept of death and dying with great caution, and explain that the decision was in “God's hands.” If the physician was uncomfortable with “God,” CAG requested that the physicians say, “It's in the hands of a higher power.”

Specific guidelines for sharing prognosis with AAs included never telling the patient that he/she is dying, under no circumstances specifying time until death, explaining what is taking place in the patient's body in non-medical terms, and always stating that the decision lies “in God's hands.” Sharing the prognosis in an insensitive, disrespectful manner or sharing it with a patient when the caregiver asks for it not to be shared by the physician were concerns raised in the White focus groups. Recommendations, therefore, included physicians respecting privacy and not sharing prognosis in a public space and/or in front of non-family members, and asking family whether they wanted to know the prognosis and then respecting their choice.

Although the word “hospice” was associated with death in both ethnic groups, in the AA group it also raised fears of strangers, White people coming into their home, and taking over. There was recognition that the AA community could benefit with education about hospice and what it offered. The AAs that had used hospice services in the care of their loved ones found some of its services, especially the support of the patient and caregiver, very beneficial. In addition to these two areas of support, the White group reported receiving support by the hospice chaplain, and support by hospice staff after the death of their loved ones. In the AA group, support was provided by the family church's pastor and family members.

Because of the concerns in both groups about the association of hospice, CAG recommendations included not using the word “hospice.” In the AA group, the physicians were asked not to raise the issue of home care unless the family asked for assistance and even then, were requested to provide reassurance that the hospice staff are not there to take over, and the family will remain in charge of taking care of their loved ones (Table 9).

Confusion between the various documents such as Advanced Care Planning, Advance Directive, Health care Power of Attorney, and Do Not Resuscitate occurred in both groups. Although only a few White focus group members had an Advanced Directive, several had seen or been asked about one. This was not the case in the AA group; here was an expressed understanding of knowing what the loved one wanted in terms of care, because the loved one had often shared it verbally with a family member, and that family member wanted to do whatever the loved one had expressed (Table 10).

An issue of concern that arose among members of both ethnic groups was lack of clarity about the administration of morphine, especially the dosage since that did not always follow usual medication regimens, as well as the possibility of lack of consciousness, and even death. The CAG members therefore made recommendations that would clearly explain this to the caregivers.

Table 11 indicates the perceived lack of needed services for those living in the rural South, such as need for specialized services for military personnel. Although the need for financial assistance for those in need was present in both groups, it was clear that in the AA group there was a lack of awareness about services that were already available in the community. This inspired the AA CAG members to create a booklet describing available services, designed specifically for older AAs, using large font and photographs of AAs using these services. These booklets were widely distributed in the AA community.

Table 12 summarizes all the recommendations for the culturally based PC consult, and it is presented side by side with the National Palliative Care Guidelines for a PC consult.20 It includes all the themes and clearly specifies which culturally based aspects are relevant to White or AA patients and families or to both groups. This is the guiding protocol that was used by the PC physician (as well as the study coordinator) to guide the PC consult in Phase 3.

Table 12.

Consult Guidelines: Culturally Based Compared to National Consensus Project Guidelines

| NCP guidelinesa | Culturally Based Guidelines |

|

|---|---|---|

| AA | White | |

| Understand distrust (AA) | ||

| Lack of trust of medical system and care. Recognize and respect that there are historical reasons for this. Work to establish trust. | ||

| Reduce distrust: AA patients/caregivers are more likely to trust AA members of their community. (1) All AA patients/caregivers will first meet an AA CAG member who will introduce them to the study (but not review consent). (2) If patient/family agree, CAG member will introduce them to the Study Coordinator who will review the consent. |

Although lack of trust was not a concern, White patients and caregivers will first meet a CAG member (W or AA) who will introduce them to the study (but not review consent). | |

| Enhance trust and address telehealth | ||

| (1) PC physician is not in same facility, pt/family need to have some indication that he/she is a clinician (doctor.) Wear White coat. | ||

| (2) Meeting patient/family via telehealth, acknowledge at the beginning of the session that this is not the same as sitting next to one another. | ||

| (d) A thorough review of: (i) medical records; (ii) relevant lab results | ||

| (e) A review of: (i) medical history; (ii) therapies; (iii) recommended treatments; and (iv) prognosis | ||

| (f) Identification of: (i) comorbid medical; (ii) cognitive; and (iii) psychiatric disorders | ||

| (g) A medication reconciliation including over-the-counter meds | ||

| Address patient and family: | ||

| Do not call patient by first name unless invited to do so. | ||

| Never be rude, always be courteous; Always respect patient confidentiality and never share prognosis in a public space, and not in front of non-family members. | ||

| (1) Introduce self (PC physician), then ask patient and caregiver and all else in room to introduce selves. Hospital staff and study coordinator last. | ||

| (2) Acknowledge telehealth medium. | ||

| Establish rapport: | ||

| Get to know the patient, establish rapport | ||

| Take and make time to get to know the patient and the family. | ||

| Learn something about the patient's family, for example, patient's past occupation, where he/she has lived. Repeat it back and converse about it. | ||

| Bring up something local, (e.g., About local geography, local history) to indicate that you know about the area. | ||

| (h) Social determinants of health, including: (i) Financial vulnerability, housing, nutrition, safety. | Recognize financial vulnerability: | |

| There are many in the AA community and some in the White Community who experience financial hardship. Recognize many experience substantial financial difficulties and the realities this brings. For example, have realistic expectations; recognize that some things that we may take for granted, for example, having A/C is not available for all. | ||

| AA community do not ask and do not know what is available. There is a need for community members to be aware of community resources. (The group developed a brochure specifically aimed at AA to bring awareness of services to AAs. Used AA visuals and large font). | ||

| (j) Patient and family emotional and spiritual concerns, including previous exposure to trauma | Understand role of religion and church: | |

| Pastors are the key to helping us understand prognosis and impending death. If prognosis is to be discussed, suggest that they may want to invite their pastors to the discussion of prognosis. Then ask name of pastor and tell them you would welcome them to the meeting. | ||

| Religion is the source of all comfort, a key value, and it is the perspective from which AAs view the world. Therefore, in all PC physician interactions with AA patients recognize and respect that this is an INTEGRAL part of all that is said and done. | Church members are a source of support for patients and family members. If patient and/or family members need support, ask whether a church member can assist. Then ask for name of church member and discuss how they can provide support. | |

| (l) Patient and family needs related to: (i) anticipatory grief; (ii) loss and bereavement including assessment of family risk for prolonged grief disorder | Understand death and dying (AA) | |

| Death is not discussed in AA church, nor in our homes. Recognize that and approach this topic (death, impending death, possibility of death) with caution. | ||

| No AA person dies alone. If they have no one, a pastor will come and sit with them so that they are not alone during the transition. | ||

| (b) Determination of (i) decision-making capacity OR (ii) identification of the person with legal decision-making authority | Understand family will take care of loved one (AA) | |

| (i) Social and cultural factors and caregiving support including: (i) caregiver willingness and capacity to meet patient needs | AA families take care of their loved ones themselves in their homes. Even if there is sacrifice, one or other family member will always be there to care for loved one. | |

| (k) The ability of the patient, family, and care providers to: (i) communicate with one another effectively: consideration of language, literacy, hearing, and cultural norms | See also: Understanding death and dying | |

| (a) Patient and family understanding of: (i) serious illness | Understand talking about prognosis | |

| (1) Ask patient/family whether they want to know prognosis. | (1) Sensitively determine whether patient/family want to know about prognosis. | |

| (2) Never be blunt. | (2) Honor their decision (i.e., if don't want to know, don't discuss and vice versa). | |

| (3) Never tell patient they are dying. | (3) Be a part of their journey. | |

| (4) If family asks prognosis, give it in range only (never give date or time). | ||

| (5) Explain reasons for what is happening in the body very simply (and do not use any medical terms). | ||

| (6) Offer opportunity for patient and family to ask questions. If family does not understand, explain it differently. It is the physician's responsibility to make sure he/she is clear and helps patient/family to understand. | ||