Abstract

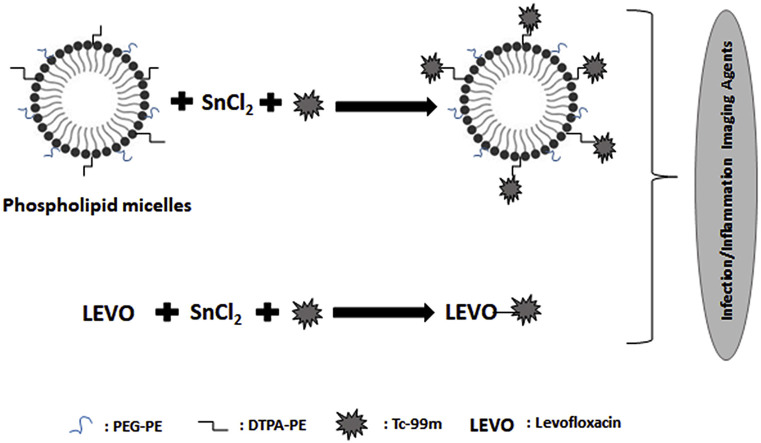

Easy and early detection of infection and inflammation is essential for early and effective treatment. In this study, PEGylated micelles were designed and both micelles and Levofloxacin were radiolabeled with 99mTcO4- to develop potential radiotracers for detection of infection/inflammation. Radiolabeling efficiency, in vitro stability and bacterial binding of 99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc-micelles were compared. The aim of this study is to formulate and compare 99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc-micelles as infection and inflammation agents having different mechanisms for the accumulation at infection and inflammation site. PEGylated micelles were designed with a particle size of 80 ± 0.7 nm and proper characterization properties. High radiolabeling efficiency was achieved for 99mTc-Levofloxacin (96%) and 99mTc-micelles (87%). The radiolabeling efficiency was remained stable with some insignificant alterations for both radiotracers at 25 °C for 24 h. Although in vitro bacterial binding of 99mTc-levofloxacine was higher than 99mTc-micelles, 99mTc-micelles may also be evaluated potential agent due to long circulation and passive accumulation mechanisms at infection/inflammation site. Both radiopharmaceutical agents exhibit potential results in design, characterization, radiolabeling efficiency and in vitro bacterial binding point of view.

Keywords: Micelles, Levofloxacin, 99mTc-radiolabeling, Infection imaging, Inflammation imaging

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

PEGylated, nanosized micelles were designed and characterized.

-

•

High radiolabeling efficiency was achieved for both Levofloxacin and micelles.

-

•

Labeling efficiency was remained stable for both radiotracers at 25 °C for 24 h.

-

•

99mTc-Levofloxacin showed high and specific bacterial binding in vitro.

-

•

99mTc-micelles showed lesser in vitro bacterial binding.

1. Introduction

The diagnosis of infections with the help of radiological imaging modalities such computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides both non-invasive diagnosis and accurate indication of the area of lesion. Depending on the basis of these anatomical imaging techniques, the infections can only be detected after formation of a morphological alteration. Therefore, early stage detections are not possible by the use of these routine medical imaging modalities especially in deeply seated infections, for example, osteomyelitis, intraabdominal infections and endocarditis. For this purpose, the use of scintigraphic imaging modalities such as gamma scintigraphy, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET) and hybrid imaging modalities comprising SPECT/CT, PET/CT, PET/MRI can provide physiologic and metabolic information about the lesion.

Specific radiopharmaceuticals have been searched for obtaining lesion imaging with physiologic and metabolic information at the early stage of microbial infections. 99mTc‐labeled leukocytes was the first radiopharmaceutical in 1980s having the ability to image deeply seated infections to indicate regions of inflammation [[1], [2], [3]]. However, the cumbrous methods are one of the most commonly faced disadvantageous [[4], [5], [6]].

Detection of infection by non-specific tracers can be performed including 67Ga-Citrate [7], radiolabeled nonspecific Immunoglobulins such as human polyclonal immunoglobulin (HIG) [8], liposomes [9], Avidin-Biotin system [10]. Apart from these non-specific tracers some specific tracers were also developed such as radiolabeled white blood cells including 111In-Oxine-labeled leukocytes [11], 99mTc-HMPAO-labeled leukocytes [12], antigranulocyte antibodies and antibody fragments [13], chemotactic peptides [14], cytokines [15], Interleukin-1 [16], Interleukin-2 [17], Interleukin-8 [18], Platelet Factor-4 [19], 18F-FDG [20], antibiotics and antimicrobial peptides [21].

Although many alternatives were exist and developed for specific and non-specific detection of infection, the development of radiolabeled antibiotics against bacteria progressed faster and gained popularity due to simple radiolabeling procedure of 99mTcO4 - and higher availability [22]. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics specifically bind and inhibit bacterial DNA gyrase. 99mTc‐Ciprofloxacin was one of the first radiolabeled antibiotics in 1990s to image microbial infections or aseptic inflammation [23]. Ciprofloxacin was labeled using formamidine sulfuric acid (FSA) as 99mTc reducing agent at 100 °C for 10 min. However, due to the instability of FSA, stannous ion has been used to increase labeling yield and reduce 99mTc to a lower oxidation state [23]. Afterwards, was 99mTc‐Ciprofloxacin was approved for infection imaging and marketed as “Infecton®” [24,25]. Other fluoroquinolone family antibiotics were also labeled for this purpose [26]. By the improvements in the production of alternative severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) antibiotics and growing drug resistance, a variety of 99mTc-labeled flouroquinolone and cephalosporin antibiotics were prepared including 99mTc‐Pefloxacin [27], 99mTc‐Lomefloxacin and 99mTc-Ofloxacin [28], 99mTc‐Sparafloxacin [29], 99mTc‐Difloxacin [30], 99mTc‐Moxifloxacin [31], 99mTc‐Gemifloxacin [32], 99mTc-Rufloxacin [33], 99mTc‐Clinafloxacin [34], 99mTc‐Sitafloxacin [35], 99mTc‐Levofloxacin [36], 99mTc‐Temafloxacin [37], 99mTc-Ceftizoxime [38], 99mTc‐Cefuroxime [5], 99mTc‐Ceftriaxone [39], 99mTc‐Cefotaxime [40] and 99mTc‐Cefoperazone [41,42].

Radiolabeled antibiotics have been used for the diagnosis of infection. The advantage of the utilization of radiolabeled antibiotics is its ability to differentiate between infection and aseptic inflammation [25,43]. Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic and belong to third-generation fluoroquinolones. It has an antibacterial activity of optically active l-isomer of ofloxacin. The antibacterial activity of Levofloxacin is due to blockage of bacterial cell growth by inhibiting DNA gyrase (bacterial topoisomerase II) which is an enzyme required for DNA replication, RNA transcription, and repair of bacterial DNA [44].

Some other agents for scintigraphic imaging were developed to perform quick and efficient imaging of inflammation and infection with high sensitivity and specificity [45,46]. Radiolabeled liposomes were designed as imaging agents for inflammation and infectious processes. It was previously demonstrated liposomes with small particle size and surface coating by a hydrophilic polymer (such as PEG) show enhanced blood circulation time providing an increased accumulation at the site of infection [[47], [48], [49], [50], [51]]. Liposomes which are formulated in a particle size of nanometer range and surface coated for passive targeting are called stealth liposomes. A variety of stealth liposomes were prepared and evaluated for this purpose [49,[52], [53], [54]]. Although many previous studies were performed for 99mTc-radiolabeling of antibiotics and liposomes, these techniques are still very valuable for their accumulation in the site of the infection and inflammation [25]. Infection specific radiopharmaceuticals can be successfully used for the diagnosis, imaging and therapy monitoring. There has been an intensive research for the development of specific infection and inflammation imaging probes because routinely used tracers in clinics still cannot evaluate infection and inflammation efficiently.

Although, micelles are another efficiently used delivery systems for imaging or therapy of many diseases, the research about the diagnosis and imaging of infection and inflammation with micelles is very limited. Micelles are formed of lipid monolayers with a fatty acid core and polar surface. Inverted micelles are defined as the vice-versa of micelles in which polar core is in the center with fatty acids on the surface. Therefore, research about the evaluation of infection and inflammation potential of micelles may be beneficial.

99mTc-Levofloxacin was radiolabeled in two studies [36,55] by different radiolabeling methods including cysteine·HCl as co-ligand. In vivo efficacy of 99mTc-Levofloxacin in infection model small animals was found high for both studies. However, in vitro bacterial binding of 99mTc-Levofloxacin was never investigated and compared with 99mTc-labeled PEGylated, phosphatidylcholine (PC), sodium dodecyl cholate (SDC) and DTPA-PE containing nanosized micelles.

In this study, PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing nanosized micelles were designed and both micelles and Levofloxacin were radiolabeled with 99mTcO4 - by tin reduction method to develop potential radiotracers for detection of infection and inflammation. The aim of this study is to formulate and compare radiolabelled micelles and radiolabelled antibacterial agent Levofloxacin as infection and inflammation agents having different mechanisms for the accumulation at infection and inflammation site. Radiolabeling of 99mTc‐Levofloxacin was evaluated with changing antibiotic concentration, reducing agent (SnCl2.2H2O) concentration, pH and incubation time. Among these processes, radioactivity was kept constant and percent labeling of 99mTc‐Levofloxacin was measured using ITLC plates. Characterization studies were performed for 99mTc-radiolabeled micelles and radiolabeling efficiency was also evaluated. Bacterial binding of 99mTc-labeled Levofloxacin and micelles were compared in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) for evaluating and comparing their in vitro bacterial binding and specificity as potential infection and inflammation imaging agents.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Levofloxacin hemihydrate was obtained from Drogsan, Turkey. Phosphatidylcholine from Soybean (98%) (PC) was a kind gift from Lipoid GmbH, Germany and sodium dodecyl cholate (SDC) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Tin(II) chloride was obtained (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for radiolabeling procedure. 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt) (PEG2000-DSPE) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., USA) was used for PEGylation. 1,2-Dioleoiyl-sn-glicero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Germany), Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid anhydride (DTPA) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Merck, Germany) were used for DTPA-PE synthesis. Membrane filters (MS® Nylon Membrane Filters, USA) were used for filtration sterilization. ITLC-SG Plates were obtained from Gelman Sci, Germany.

2.2. Radiolabeling of Levofloxacin

This was performed to determine the best conditions for the labeling of Levofloxacin with 99mTcO4 -. Labeling efficiency was calculated by changing SnCl2.2H2O concentrations from 15 to 150 μg, Levofloxacin concentration from 0.5 to 3 mg, pH from 3 to 7 and incubation time from 15 to 120 min with the same amount of sodium pertechnetate (5 mCi) which was freshly eluted from 99Mo/99mTc generator. The pH was arranged by using 0.1 N HCl and NaOH solutions [36,55].

2.3. Radiochemical analysis

Radiochemical purity was evaluated by ITLC by using miniaturized ITLC-SG Plates to evaluate the percentage of unbound pertechnetate (99mTcO4 -) and hydrolyzed/reduced technetium (99mTcO2) by using acetone and saline as running solvents, respectively. 99mTc-Levofloxacin was spotted at ITLC plates. The radiochemical purity of 99mTc-Levofloxacin was measured by the using Equation (1) [36,55].

| %Colloid=(Activity before filtration–Activity after filtration)/Activity before filtration × 100 |

| %Free Pertechnetate (99mTcO4-) = (Activity at Rf 0.75 to 1.0/Total activity) × 100 |

| %99mTc-Levofloxacin = 100−(%Colloid+% 99mTcO4−) | (1) |

For the purpose of obtaining efficient and maximum radiolabeling, optimum amount of Levofloxacin, reducing agent, pH and incubation time were evaluated. The highest radiolabeling yield was calculated after passing 99mTc-Levofloxacin through a 0.22 μm filter and by ITLC analysis [36,42,44,55].

2.4. Synthesis of DTPA-PE

DTPA-PE was used as chelating agent for radiolabeling of micelles. It was synthetized by mixing 0.1 mM of DOPE in 4 mL of chloroform, supplemented with 30 μL of triethylamine. This was then added to 1 mM of DTPA anhydride in 20 mL of DMSO by stirring. This mixture was incubated for 3 h at 25 °C under argon gas. Afterwards, the solution was dialyzed against 6 L of water at 4 °C for 48 h. Purified DTPA-PE was freeze-dried and stored frozen at −80 °C [56,57].

2.5. Preparation of micelles

Film forming method was used for the preparation of PEGylated DTPA-PE containing micelles containing PC:PEG2000-DSPE:SDC:DTPA-PE (55:0.9:44:0.1 in % molar ratios). Lipids (15 mg total lipids/mL) were dissolved in chloroform which was evaporated at 40 °C under reduced pressure. After removing of the solvent, lipid film was hydrated by HEPES (1 M, pH 7.4) buffer at 30 °C. Afterwards, the vesicles were dispersed for 15 min via ultrasonicator [58,59].

2.6. Characterization of micelles

The characterization of PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing nanosized micelles was determined by measuring mean particle size and zeta potential.

2.6.1. Mean particle size and zeta potential

Mean particle size, polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential of micelles were measured using the Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) by dynamic light scattering method at 25 °C.

2.7. Radiolabeling of PEGylated micelles

PEGylated, PC and SDC containing micelles including amphiphilic chelating agent DTPA-PE were labeled with 99mTcO4 - by tin reduction method. In brief, 0.5 mL SnCl2.2H2O (1 mg mL−1) and (1.5 mCi) 99mTcO4 - were incubated with micelles for 30 min to perform trans-chelation of 99mTc with micelles. Afterwards, samples were dialyzed against HEPES Buffer (pH 7.4) for 5 h at 4 °C to remove un-chelated 99mTc by using cellulose ester dialysis tubes (3500 Da cut-off size). Quality control of binding was checked by ITLC-SG Plates in saline and acetone as running solvent system. After completion of the development procedure, strips were cut and measured in a well type gamma counter.

2.8. In vitro stability studies

In vitro stability of 99mTc-Levofloxacin and radiolabeled, PEGylated, PC and SDC containing micelles was determined at room temperature in the presence of saline (NaCl 0.9% (w/v)) or serum. For this purpose, 0.1 mL of samples were added to 0.9 mL of saline or equal volume of cell culture medium (PBS) supplemented with 10% FBS. Afterwards, they were analyzed after incubation with ITLC at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h to estimate the radiochemical stability of 99mTc-Levofloxacin and radiolabeled micelles [55].

2.9. In vitro binding assay with bacteria

In vitro binding efficiency of 99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc radiolabeled PEGylated PC:SDC micelles were investigated against S. aureus and E. coli. For the evaluation of bacterial binding, 0.9 mL of a bacterial suspension containing approximately 108 CFU was taken, and exactly 0.1 mL of PBS containing approximately 1 mCi of radiolabeled Levofloxacin or micelles were added to the test tubes. The mixtures were then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Afterwards, they were centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm at 4 °C and the pellets were then resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. The resuspended pellets were centrifuged for 5 min, the supernatants were separated and 1 mL of PBS was added. The supernatants were removed and the radioactivity in the bacterial pellets were determined by well-type gamma counter. The bacterial binding of radiopharmaceuticals was calculated according to Equation (2) [[60], [61], [62]].

| Bacterial Binding(%) = Counts in Pellet/(Counts in Supernatant + Counts in Pellet)x100. | (2) |

2.10. Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as the mean ± SD and n = 6. Non-parametric test methods were used for the evaluation of number of data less than 30. Depending on the group number, Student T test was used for the comparison of two groups and the Kruskal Wallis was used for the comparison of three or more groups. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc-radiolabeled micelles were prepared for the purpose of effective infection and inflammation imaging.

3.1. The characterization of 99mTc radiolabeled, PEGylated micelles

PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing nanosized micelles were prepared and radiolabeled for imaging of infection and inflammation. The characterization of micelles was performed by measuring particle size and zeta potential. The average particle size of micelles was 80 ± 0.7 nm, polydispersity index was 0.14 and the zeta potential was 21.15 ± 1.2 mV.

3.2. Radiochemical purity of 99mTc radiolabeled, PEGylated micelles

Nanosized, PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing micelles show a high labeling efficiency (87 ± 1.21%).

3.3. Radiolabeling process and quality control of 99mTc-Levofloxacin

The optimization of radiolabeling provides the best conditions to obtain maximum labeling efficiency. 99mTc radiolabeling of Levofloxacin was tried in varying conditions and the labeling yield was optimized.

3.3.1. Effect of Levofloxacin amount

The radiolabeling efficiency of Levofloxacin was performed in varying concentrations (0.5–3 mg) with the same amount of radioactivity. The best radiolabeling efficiency of Levofloxacin was 96 ± 2.12% which was achieved by addition of 1 mg Levofloxacin. It was observed that lesser amounts of Levofloxacin resulted in decreased labeling efficiency. The radiolabeling efficiency of 0.5 mg of Levofloxacin was 83%. Higher amounts than 1 mg resulted no significant alteration on the labeling efficiency. Our findings were in agreement with the literature [55].

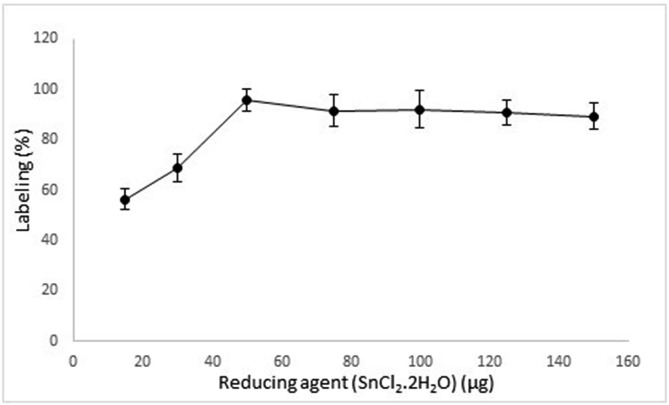

3.3.2. Effect of reducing agent

Reducing agent (SnCl2.2H2O) was used in the range of 15–150 μg for the evaluation of optimum amount of SnCl2.2H2O to achieve highest labeling efficiency. It was observed that at low amounts of reducing agent, the labeling efficiency was very low (~57%). The highest radiolabeling efficieny was obtained at 50 μg mL−1 of SnCl2.2H2O (~96%). It may be concluded that lower amounts (lower than 50 μg mL−1) of reducing agent can not effectively reduce whole 99mTcO4 − for the labeling process (Fig. 1 ). This observation was in agreement with previous studies [36].

Fig. 1.

The effect of SnCl2.2H2O on labeling efficiency.

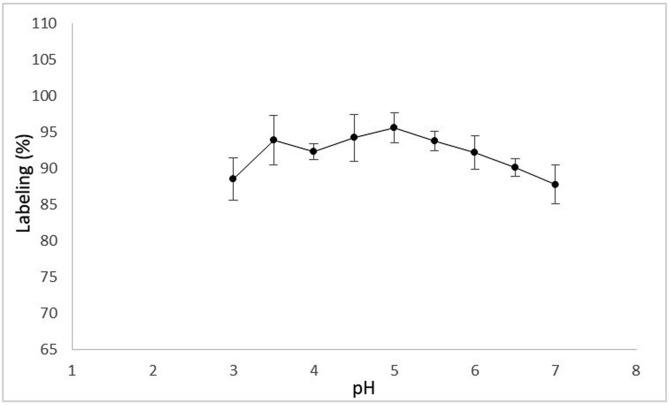

3.3.3. Effect of pH

Different pH values (pH:3–7) were evaluated for determining the effect of pH in radiolabeling efficieny. Any significant difference in labeling yield at acidic conditions was observed. On the other hand, the labeling efficiency decreased at slight basic pH which may be due to any possible change in the structure of the Levofloxacin related with carboxylic moiety at basic pH (Fig. 2 ). Its carboxylic moiety may be neutralized to prevent labeling with 99mTcO4 - during the metal exchange reaction. The maximum radiolabeling (96%) was achieved at pH:5. Higher and lower pH values cause decrease in labeling efficiency. This observation was in paralell with other studies [36,55].

Fig. 2.

The effect of pH on labeling efficiency.

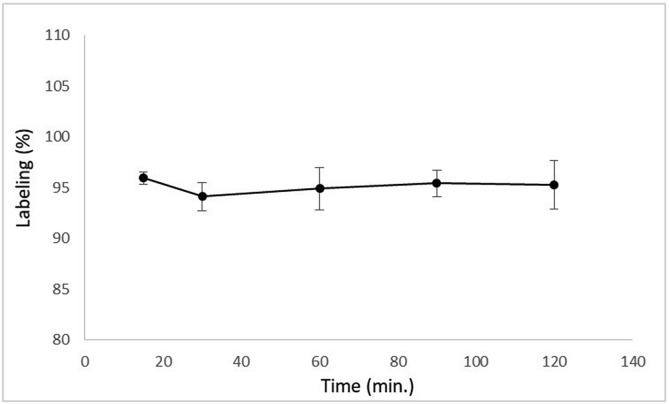

3.3.4. Effect of incubation time

Incubation time is an essential parameter in radiolabeling efficiency of radiopharmaceuticals. The effect of incubation time on labeling efficiency of 99mTc-Levofloxacin was given in Fig. 3 . Maximum radiolabeling efficiency (96%) was obtained after 15 min of incubation of Levofloxacin with sodium pertechnetate. It was observed that longer incubation time did not cause any significant difference in the radiolabeling efficiency which was in agreement with the literature [36].

Fig. 3.

The effect of incubation time on labeling efficiency.

After evaluation of the effects of changing antibiotic concentration, reducing agent concentration and pH, it was concluded that maximum labeling efficiency was achieved by using 1 mg Levofloxacin, 50 μg SnCl2.2H2O were dissolved in 1 mL of saline at pH 5 and incubated with Sodium pertechnetate (5 mCi) for 15 min. Afterwards, radiolabeled Levofloxacin was filtered through 0.22 μm filter at room temperature. The highest radiolabeling yield was observed as 96 ± 2.13% which was in paralell with previous studies [36,55].

3.4. In vitro stability studies

According to the stability test performed at room temperature (25 °C), the radiolabeling efficiency was remained stable with some insignificant alterations and degradations carried out at 25 °C for 24 h (Table 1 ). Any significant difference was not observed in the serum and saline stability of 99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc-micelles which were in agreement with the literature [36,55,63,64].

Table 1.

In vitro stability of labeling efficiency of99mTc-Levofloxacin and99mTc-PC:SDC micelles at room temperature.

| Radiotracers | Medium | Labeling Efficiency (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 24 | ||

| 99mTc-Levofloxacin | Serum | 95.86 ± 1.32 | 95.01 ± 0.87 | 94.90 ± 2.43 | 94.51 ± 3.24 | 93.83 ± 1.92 | 93.13 ± 1.97 |

| Saline | 96.00 ± 0.98 | 95.07 ± 2.12 | 95.04 ± 1.98 | 94.08 ± 2.89 | 94.42 ± 3.76 | 93.97 ± 2.23 | |

| 99mTc-PC:SDC Micelles | Serum | 85.01 ± 0.87 | 84.08 ± 1.36 | 84.07 ± 2.65 | 84.02 ± 3.79 | 83.60 ± 4.70 | 83.59 ± 3.75 |

| Saline | 84.97 ± 1.12 | 84.68 ± 1.79 | 84.42 ± 3.12 | 83.87 ± 2.31 | 83.54 ± 2.86 | 83.12 ± 3.73 | |

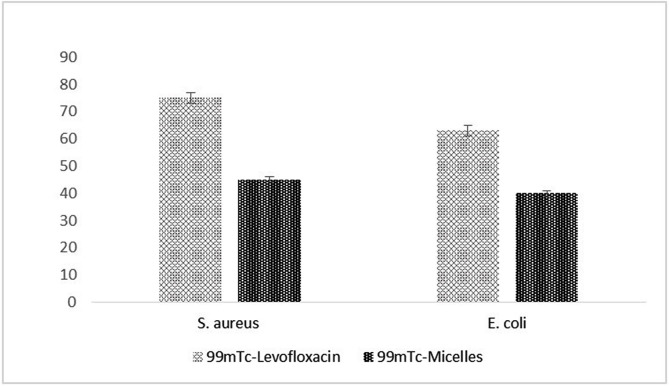

3.5. In vitro bacterial binding

In vitro bacterial binding of radiolabeled Levofloxacin and micelles after S. aureus incubation at 37 °C was observed as 75 ± 1.3% and 45 ± 2.1%, respectively. In vitro E. coli binding of radiolabeled Levofloxacin and micelles at 37 °C showed 63 ± 2.4% and 40 ± 1.9%, respectively (Fig. 4 ). Both radiolabeled Levofloxacin and micelles show high in vitro bacterial binding. Tc-99 m radiolabeled PC:SDC micelles exhibit lesser bacterial binding for both S. aureus and E. coli cultures (p < 0,05). This may be due to the fact that 99mTc-radiolabeled PC:SDC micelles are not specific to bacterial infections as much as 99mTc-Levofloxacin. However, Tc-99 m radiolabeled PC:SDC micelles can also be assumed as sensitive radiopharmaceutical agents due to the mechanism of imaging of infection and inflammation. 99mTc-radiolabeled, PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing nanosized micelles can accumulate at infection and inflammation sites due to long vascular circulation of vesicles by small particle size and surface coating by an hydrophilic polymer (such as PEG) [47,[52], [53], [54]]. It was reported in some previous studies that the accumulation of radiolabeled liposomes in at infectious sites is performed by leakage of the vesicles through vessels. This leakage depends on the enhanced vascular permeability and following phagocythosis by macrophages of infected tissue. It was reported that the endothelial junctions existing in the blood vessel provides the penetration of the particles smaller than 200 nm from the vascularization [48,54]. Therefore, surface coated, nanosized drug delivery systems like liposomes can be accumulated at the site of infection and inflammation due to long circulation, enhanced vascular permeability and reduced removal by opsonisation [49,52,65].

Fig. 4.

In vitro bacterial binding of 99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc-micelles after S. aureus and E.coli incubation at 37 °C.

Therefore, 99mTc-Levofloxacin and 99mTc-radiolabeled, nanosized, PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing micelles were observed as potential imaging agents for the diagnosis and imaging of inflammation and infectious sites [66]. Despite, radiolabelled antibiotics could represent a promising tool for specifically image infective processes, radiolabelled micelles do not show a similar specific mechanism of accumulation in infectious/inflammatory sites that is mainly due to increased permeability (that is present in both infective and inflammatory processes) and small particle size. Therefore, this “passive” and non-specific mechanism implies that they could be useful for monitoring the inflammatory burden but, since radiolabelled micelles are not able to discriminate between an infection from a sterile inflammation, their use for imaging of infections is limited in clinical practice.

4. Conclusion

Radiolabeled compounds and nanocarriers lead to direct researchers toward easy and quick diagnosis and imaging of infection and inflammation. Although, radiolabeled Levofloxacin is particularly an excellent alternative for the detection of chronic infections caused by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, radiolabeled PEGylated, PC, SDC and DTPA-PE containing nanosized micelles were also evaluated as a potential candidate in the detection of infection and inflammation. As it was known, micelles similar to liposomes tend to accumulate at the site of infection based on the long vascular circulation of vesicles by small particle size and surface coating by a hydrophilic polymer (such as PEG). Both radiopharmaceutical agents exhibit potential results in design, characterization, radiolabeling efficiency and in vitro bacterial binding point of view. In vivo potential of radiolabeled Levofloxacin and micelles should also be evaluated in the infection and inflammation animal models in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Asuman Yekta Ozer: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors state no decleration of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors want to thank to Lipoid GmbH (Ludwigshafen, Germany) and Dr. Yasemin Cirpanli for the generous gifts of Phosphatidylcholine from Soybean (98%) and Levofloxacin, respectively.

Contributor Information

Mine Silindir-Gunay, Email: mines@hacettepe.edu.tr.

Asuman Yekta Ozer, Email: ayozer@hacettepe.edu.tr.

References

- 1.Kelbæk H., Fogh J., Gjørup T., Bülow K., Vestergaard B. Scintigraphic demonstration of subcutaneous abscesses with 99mTc‐labeled leuckocytes. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1985;10:302–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00251300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hovi I., Taavitsainen M., Lantto T., Vorne M., Paul R., Remes K. Technetium‐99m‐HMPAO‐labeled leukocytes and technetium-99m labeled human polyclonal immunoglobulin G in diagnosis of focal purulent disease. J. Nucl. Med. 1993;34:1428–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutfilen B., Pellini M.P., de Roure Neder J., de Amarante J.L.M., Evangelista M.G., Fernandes S.R., Filho M.B. 99mTc labelling white blood cells with a simple technique clinical application. Ann. Nucl. Med. 1994;8:85–89. doi: 10.1007/BF03164991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El‐Ghany E.A., El‐Kolaly M.T., Amine A.M., El‐Sayed A.S., Abdel‐Gelil F. Synthesis of 99mTc‐pefloxacin: a new targeting agent forinfectious foci. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2005;266:131–139. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yurt Lambrecht F., Yilmaz O., Unak P., Seyitoglu B., Durkan K., Baskan H. Evaluation of 99mTc‐cefuroxime axetil for imaging of inflammation. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2008;277:491–494. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yurt Lambrecht F., Durkan K., Unak P. Preparation, quality control and stability of 99mTc‐cefuroxime axetil. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2008;275:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palestro C.J. The current role of gallium imaging in infection. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1994;24:128–141. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(05)80227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerasimou G., Moralidis E., Papanastasiou E., Liaros G., Aggelopoulou T., Triantafyllidou E., Lytras N., Settas L., Gotzamani-Psarrakou A. Radionuclide imaging with human polyclonal immunoglobulin (99mTc-HIG) and bone scan in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and serum-negative polyarthritis. Hippokratia. 2011;15:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dams E.T., Oyen W.J., Boerman O.C., Storm G., Laverman P., Kok P.J., Buijs W.C., Bakker H., van der Meer J.W., Corstens F.H. 99mTc-PEG liposomes for the scintigraphic detection of infection and inflammation: clinical evaluation. J. Nucl. Med. 2000;41:622–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain A., Cheng K. The principles and applications of avidin-based nanoparticles in drug delivery and diagnosis. J. Contr. Release. 2017;245:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palestro C.J., Mehta H.H., Patel M., Freeman S.J., Harrington W.N., Tomas M.B., Marwin S.E. Marrow versus infection in the Charcot joint: indium-111 leukocyte and technetium-99m sulfur colloid scintigraphy. J. Nucl. Med. 1998;39:346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erba P.A., Conti U., Lazzeri E., Sollini M., Doria R., De Tommasi S.M., Bandera F., Tascini C., Menichetti F., Dierckx R.A., Signore A., Mariani G. Added value of 99mTc-HMPAO-labeled leukocyte SPECT/CT in the characterization and management of patients with infectious endocarditis. J. Nucl. Med. 2012;53:1235–1243. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker W., Goldenberg D.M., Wolf F. The use of monoclonal antibodies and antibody fragments in the imaging of infectious lesions. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1994;24:142–153. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(05)80228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corstens F.H., van der Meer J.W. Chemotactic peptides: new locomotion for imaging of infection? J. Nucl. Med. 1991;32:491–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Signore A., Procaccini E., Annovazzi A., Chianelli M., van der Laken C., Mire-Sluis A. The developing role of cytokines for imaging inflammation and infection. Cytokine. 2000;(12):1445–1454. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni V., Cai M., Barber C., Wan L., Woolfenden J., Liu Z. 99mTc-Labeled interleukin-1 antagonist peptide for inflammation imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2013;54:1091. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung K. 99mTc-Interleukin-2. MICAD. 2006;1:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross M.D., Shapiro B., Fig L.M., Steventon R., Skinner R.W.S., Hay R.V. Imaging of human infection with 131I-labeled recombinant human Interleukin-8. J. Nucl. Med. 2001;42:1656–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moyer B.R., Vallabhajosula S., Lister-James J. Technetium-99m-white blood cell-specific imaging agent developed from platelet factor 4 to detect infection. J. Nucl. Med. 1996;37:673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Love C., Tomas M.B., Tronco G.G. FDG PET of infection and inflammation. Radiogragphics. 2005;25:1357–1368. doi: 10.1148/rg.255045122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lupetti A., Welling M.M., Mazzi U., Nibbering P.H., Pauwels E.K. Technetium-99m labelled fluconazoleand antimicrobial peptides for imaging of Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatusinfections. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2002;29:674–679. doi: 10.1007/s00259-001-0760-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhtar M.S., Imran M.B., Nadeem M.A., Shahid A. Antimicrobial peptides as infection imaging agents: better than radiolabeled antibiotics. Int. J. Peptides. 2012;1:1–19. doi: 10.1155/2012/965238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solanki K., Bomanji J., Siraj Q., Small M., Britton K. Tc‐99m Infecton‐a new class of radiopharmaceutical for imaging infection. J. Nucl. Med. 1993;34:119–121. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinjamuri S., Solanki K.K., Bomanji J., Siraj Q., O'Shaughnessy E., Das S.S., Britton K.E. Comparison of 99mTc infection imaging with radiolabelled white‐cell imaging in the evaluation of bacterial infection. Lancet. 1996;347:233–235. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malamitsi J., Giamarellou H., Kanellakopoulou K., Dounis E., Grecka V., Christakopoulos J., Koratzanis G., Antoniadou A., Panoutsopoulos G., Batsakis C., Proukakis C. Infecton: a 99mTc‐ciprofloxacin radiopharmaceutical for the detection of bone infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003;9:101–109. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siaens R.H., Rennen H.J., Boerman O.C., Dierckx R., Slegers G. Synthesis and comparison of 99mTc‐enrofloxacin and 99mTc‐ciprofloxacin. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:2088–2094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Ghany E.A., El-Kolaly M.T., Amine A.M., El-Sayed A.S., Abdel-Gelil F. Synthesis of 99mTc-pefloxacin: a new targeting agent for infectious foci. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2005;266:131–139. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motaleb M.A. Preparation and biodistribution of 99mTc‐lemofloxacin and 99mTc‐ofloxacin complexes. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2007;272:95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motaleb M.A. Preparation quality control and stability of 99mTc-sparafloxacin complex, a novel agent for detecting sites of infection. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2009;52:415–418. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motaleb M.A. Radiopharmaceutical and biological characteristics of 99mTc‐difloxacin & 99mTc‐pefloxacin for detecting sites of infection. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2010;53:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chattopadhyay S., Saha Das S., Chandra S., De K., Mishra M., Ranjan Sarkar B., Sinha S., Ganguly S. Synthesis and evaluation of 99mTc‐moxifloxacin, a potential infection specific imaging agent. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2010;68:314–316. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah S.Q., Khan M.R. Radiolabeling of gemifloxacin with technetium‐99m and biological evaluation in artificially Streptococcus pneumonia infected rats. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011;288:307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah S.Q., Khan M.R. Radiocharacterization of the 99mTc‐rufloxacin complex and biological evaluation in staphylococcus aureus infected rat model. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011;288:373–378. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah S.Q., Khan M.R. Synthesis of technetium‐99m labelled clinafloxacin (99mTc‐CNN) complex and biological evaluation as a potential staphylococcus aureus infection imaging agent. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011;288:423–425. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qaiser S.S., Khan A.U., Khan M.R. Synthesis, biodistribution and evaluation of 99mTc‐sitafloxacin kit: a novel infection imaging agent. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010;284:189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naqvi S.A.R., Ishfaq M.M., Khan Z.A., Nagra S.A., Bukhari I.H., Hussain A.I., Mahmood N., Shahzad S.A., Haque A., Bokhari T.H. 99mTc labeled levofloxacin as an infection imaging agent a novel method for labelling levofloxacin using cysteine.HCl as co‐ligand and in vivo study. Turk. J. Chem. 2012;36:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah S.Q., Khan M.R. Synthesis of 99mTc labeled Temafloxacin complex and biodistribution in male Wistar rats artificially infected with streptococci pneumonia. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013;22:319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diniz S.O.F., Siqueira C.F., Nelson D.L., Martin‐Comin J., Cardoso V.N. Technetium‐99m Ceftizoxime kit preparation. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2005;48:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mostafa M., Motaleb M.A., Sakr T.M. Labeling of ceftriaxone for infective inflammation imaging using 99mTc eluted from 99Mo/99mTc generator based on zirconium molybdate. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2010;68:1959–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirshojaei S.F., Erfani M., Shafiei M. Evaluation of 99mTc-ceftazidime as bacterial infection imaging agent. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2013;298:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s10967-013-2464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Motaleb M.A. Preparation of 99mTc‐cefoperazone complex, a novel agent for detecting sites of infection. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2007;272:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasheed R., Naqvi S.A.R., Gillani S.J.H., Zahoor A.F., Jielani A., Saeed N. 99mTc‐tazobactam, a novel infection imaging agent: radiosynthesis, quality control, biodistribution, and infection imaging studies. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2017;60:242–249. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welling M.M., Paulusma-Annema A., Balter H.S., Pauwels E.K., Nibbering P.H. Technetium-99m labelled antimicrobial peptides discriminate between bacterial infections and sterile inflammations. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2000;27:292–301. doi: 10.1007/s002590050036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sierra J.M., Rodriguez-Puig D., Soriano A., Mensa J., Piera C., Vila J. Accumulation of 99mTc-ciprofloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2691–2692. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00217-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Eerd J.E.M., Broekema M., Harris T.D., Edwards D.S., Oyen W.J.G., Corstens F.H.M., Boerman O.C. Imaging of infection and inflammation with an improved 99mTc-labeled LTB4 antagonist. J. Nucl. Med. 2005;46:1546–1551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Love C., Palestro C.J. Radionuclide imaging of infection. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2004;32:47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Awasthi V.D., Garcia D., Goins B.A., Phillips W.T. Circulation and biodistribution profiles of long-circulating PEG-liposomes of various sizes in rabbits. Int. J. Pharm. 2003;253:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00703-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crommelin D.J.A., Van Rensen A.J.M.L., Wauben M.H.M., Storm G. Liposomes in autoimmune diseases: selected applications in immunotherapy and inflammation detection. J. Contr. Release. 1999;62:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erdogan S., Ozer A.Y., Ercan M.T., Hincal A.A. Scintigraphic imaging of infections with 99mTc-labelled glutathione liposomes. J. Microencapsul. 2000;17:459–465. doi: 10.1080/026520400405714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boerman O.C., Oyen W.J., Van Bloois L., Koenders E.B., Van Der Meer J.W., Corstens F.H.M., Storm G. Optimization of technetium-99m-labeled PEG liposomes to image focal infection: effects of particle size and circulation time. J. Nucl. Med. 1997;38:489–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Litzinger D.C., Buiting A.M.J., Van Rooijen N., Huang L. Effect of liposome size on the circulation time and intraorgan distribution of amphipathic poly(ethylene glycol)-containing liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1190:99–107. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goins B., Klipper R., Rudolph A.S., Cliff R.O., Blumhardt R., Phillips W.T. Biodistribution and imaging studies of Technetium-99m-labeled liposomes in rats with focal infection. J. Nucl. Med. 1993;34:2160–2168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dams E.T.M., Oyen W.J.G., Boerman O.C., Storm G., Laverman P., Kok P.J.M., Buijs W.C.A.M., Bakker H., van der Meer J.W.M., Corstens F.H.M. 99mTc-PEG liposomes for the scintigraphic detection of infection and inflammation: clinical evaluation. J. NucI. Med. 2000;41:622–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carmo V.A.S., de Oliveira M.C., das Graças Mota L., Freire L.P., Ferreira R.L.B., Cardoso V.N. Technetium-99m-labeled stealth pH-sensitive liposomes: a new strategy to identify infection in experimental model. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2007;50:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shahzad S., Qadir M.A., Rasheed R., Anwar S., Ahmed M. In vivo studies 99mTc-Levofloxacin freeze dried kits in Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2015;34:760–765. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grant C.W., Stephen K., Florio E. A liposomal MRI contrast agent: phosphatidylethanolamine-DTPA. Magn. Reson. Med. 1989;11:236–243. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910110211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elbayoumi T.A., Torchilin V. Enhanced accumulation of longcirculating liposomes modified with the nucleosome-specific monoclonal antibody 2C5 in various tumours in mice: gammaimaging studies. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imag. 2006;33:1196–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarisozen C., Vural I., Levchenko T., Hincal A.A., Torchilin V.P. Long-circulating PEG-PE micelles co-loaded with paclitaxel and elacridar (GG918) overcome multidrug resistance. Drug Deliv. 2012;19:363–370. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2012.724473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duan Y., Wang J., Yang X., Du H., Xi Y., Zhai G. Curcumin-loaded mixed micelles: preparation, optimization, physicochemical properties and cytotoxicity in vitro. Drug Deliv. 2015;22:50–57. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2013.873501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaul A., Hazari P.P., Rawat H., Singh B., Kalawat T.C., Sharma S., Babbar A.K., Mishra A.K. Preliminary evaluation of technetium-99m-labeled ceftriaxone: infection imaging agent for the clinical diagnosis of orthopedic infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;17:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shahzadi S.K., Qadir M.A., Shahzad S., Javed M. 99mTc-amoxicillin: a novel radiopharmaceutical for infection imaging. Arab. J. Chem. 2015;xxx:xxx–xxxx. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mirshojaei S.F., Erfani M., Sadat-Ebrahimi S.E., Talebi M.H., Abbasi F.H.H. Freeze-dried cold kit for preparation of 99mTc-ciprofloxacin as an infection imaging agent. Iran. J. Nucl. Med. 2010;18:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duan Y., Wei L., Petryk J., Ruddy T.D. Formulation, characterization and tissue distribution of a novel pH-sensitive long-circulating liposome-based theranostic suitable for molecular imaging and drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016;11:5697–5708. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S111274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monteiro L.O.F., Fernandes R.S., Castro L.C., Cardoso V.N., Oliveira M.C., Townsend D.M., Ferretti A., Rubello D., Leite E.A., de Barros A.L.B. Technetium-99m radiolabeled paclitaxel as an imaging probe for breast cancer in vivo, Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;89:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laverman P., Dams E.T., Storm G., Hafmans T.G., Croes H.J., Oyen W.J., Corstens F.H.M., Boerman O.C. Microscopic localization of PEG-liposomes in a rat model of focal infection. J. Contr. Release. 2001;75:347–355. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boerman O.C., Laverman P., Oyen W.J.G., Corstens F.H.M., Storm G. Radiolabeled liposomes for scintigraphic imaging. Prog. Lipid Res. 2000;39:461–475. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(00)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]