Abstract

The biosynthesis of fusion-competent envelope glycoproteins (GPs) is a crucial step in productive viral infection. In this issue, Klaus et al. (2013) identify the cargo receptor endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi intermediate compartment 53 kDa protein (ERGIC-53) as a binding partner for viral GPs and a crucial cellular factor required for infectious virus production.

Main Text

Over the past decades, several enveloped viruses of the arenavirus, filovirus, hantavirus, and coronavirus families have emerged as causative agents of severe human disease with high mortality. Considering the current lack of licensed vaccines and the limited therapeutic options at hand, the development of novel antiviral drugs against these pathogens is urgently needed. A major challenge for the development of efficacious drugs against emerging viruses is frequently the limited molecular information available. However, as for all viruses, these emerging enveloped viruses critically depend on the molecular machinery of the host cell for their multiplication. Therefore, targeting cellular factors represents a promising approach for therapeutic intervention.

A crucial step in the multiplication of enveloped viruses is the biosynthesis of the fusion-competent envelope glycoprotein (GP) that decorates the virion surface and mediates host cell attachment and entry. Enveloped viruses hijack the host cell’s secretory pathway for GP biosynthesis. En route through the secretory pathway, viral GPs are subject to posttranslational modifications, including N- and O-glycosylation and, in many cases, proteolytic processing by cellular proteases. While much has been learned in the past years about the nature of these modifications and their role in GP stability and biological function, the specific nature of the cellular factors implicated in GP synthesis, transport, and maturation is only partially understood. In this issue of Cell Host & Microbe, Klaus et al. (2013) sought to close this gap by performing a broad proteomic screen to identify cellular proteins that interact with viral envelope GPs. Using the GPs of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and the New World hantavirus Andes (ANDV) as baits, an unbiased screen was carried out, employing a pull-down approach, combined with mass spectrometry analysis. The screening results revealed complex interaction patterns for both viral GPs, including numerous candidate cellular proteins. Despite remarkable differences in their interactomes, both LCMV and ANDV GPs were found to associate with a set of common cellular proteins.

Among the candidate proteins present in both sets, a mannose-specific membrane lectin associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC), ERGIC-53, was of particular interest (Itin et al., 1996, Schweizer et al., 1988). In mammalian cells, the ERGIC is a system of tubulovesicular membrane clusters located between the rough ER and the Golgi. ER-derived cargo traffics to ERGIC-53-positive compartments, followed by a second vesicular transport step toward the Golgi (Appenzeller-Herzog and Hauri, 2006). ERGIC-53 functions as a cargo receptor for the transport of cellular glycoproteins from the ER to the Golgi. A deficiency in ERGIC-53 results in a selective defect in glycoprotein secretion and, in humans, manifests as combined factor V-factor VIII deficiency (F5F8D), a rare, autosomal recessive coagulation disorder characterized by reduced levels of both coagulation factors V and VIII (Neerman-Arbez et al., 1999).

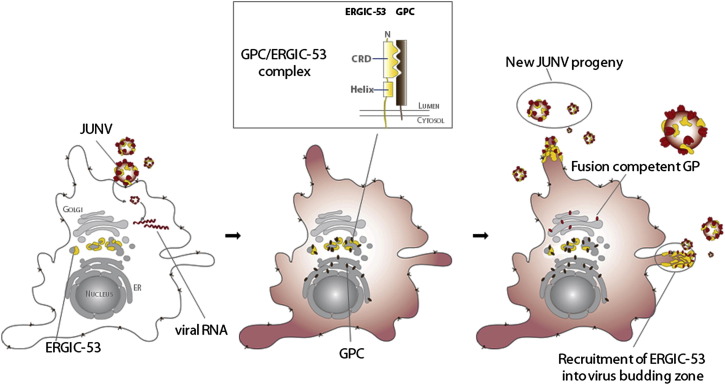

ERGIC-53 was found to specifically interact with a broad spectrum of class I viral fusion proteins derived from several arenaviruses, hantaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, influenza virus, and filoviruses. However, ERGIC-53 was unable to recognize the G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus, which structurally belongs to another class of viral fusion proteins. This suggests some specificity for class I viral GPs, a notion that is supported by the recently reported interaction of ERGIC-53 with the envelope GP of HIV (Jäger et al., 2012). Remarkably, ERGIC-53 preferentially associated with the immature GP precursors, pinpointing early compartments of the secretory pathway as sites of interaction (Figure 1 ). Employing a comprehensive set of functional assays, a strong case is made for a role of ERGIC-53 in productive viral infection. Using a combination of gene silencing by RNAi, overexpression, and dominant-negative (DN) mutants, evidence is provided that ERGIC-53 is crucial for cell-to-cell propagation of arenaviruses. These data are complemented by impaired productive infection in cells derived from patients bearing an ERGIC-53 null mutation. As anticipated from the interaction data, the effect of ERGIC-53 mapped to the viral GP. Notably, cellular ERGIC-53 was dispensable for viral entry, suggesting a role in a later step of the viral life cycle.

Figure 1.

ERGIC-53 Is Crucial for the Formation of Infectious Arenavirus Particles

In uninfected cells, ERGIC-53 is largely confined to the ERGIC compartment and recycles from the Golgi. Early during infection with the arenavirus Junin virus (JUNV), the GP precursor (GPC) associates with ERGIC-53, likely in an early compartment of the secretory pathway. The luminal carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) of ERGIC-53 is required for the interaction that seems otherwise distinct from the lectin-type binding of cellular cargo. Viral infection results in trafficking of ERGIC-53 to the cell surface, where incorporation into budding virions occurs. The infectivity of progeny virions critically depends on the presence of ERGIC-53 in their envelope.

Formation and release (budding) of arenavirus infectious progeny from infected cells requires that assembled viral ribonucleoprotein cores associate at the cell surface with membranes enriched in viral GPs. Considering the function of ERGIC-53 as a cargo receptor implicated in traffic from the ER to the Golgi, a possible role in GP transport and maturation was assessed. Rather unexpectedly, the absence of ERGIC-53 had no effect on the transport and posttranslational processing of the viral GP. Characterization of virus-like particles and authentic virions produced in ERGIC-53-deficient cells revealed efficient incorporation of GP into particles that showed normal composition but had markedly reduced infectivity. Under normal conditions, ERGIC-53 does not traffic beyond the cis-Golgi (Appenzeller-Herzog and Hauri, 2006). However, viral infection resulted in the appearance of ERGIC-53 at the cell surface where virion budding occurs, indicating virus-induced changes in trafficking of the cargo receptor (Figure 1). ERGIC-53 was found to be incorporated into budding virions, and its presence was crucial for infectivity. Initial characterization of the interaction between arenavirus GP and ERGIC-53 revealed that the carbohydrate recognition domain was critical. However, in contrast to ERGIC-53’s lectin-type binding to cellular cargo, recognition of viral GP was independent of its capacity to oligomerize or bind mannose and did not require Ca2+ ions.

The discovery of a role for the cellular cargo receptor ERGIC-53 in infectious virus production is an exciting finding that further illuminates the process of enveloped virion maturation. The ability of ERGIC-53 to recognize the precursors of a wide variety of class I viral fusion proteins derived from phylogenetically distant viral families suggests an evolutionarily conserved function. It will be of interest to extend the screen to enveloped RNA viruses with class II fusion proteins and enveloped DNA viruses. The present study provides compelling evidence for virus-induced changes in ERGIC-53 trafficking, indicating that viruses can reshape the subcellular distributions of components of the secretory pathway to optimize production of infectious progeny. Previous studies revealed that the cell’s unfolded protein response (UPR) can induce ERGIC-53 trafficking to the cell surface (Nyfeler et al., 2003), and activation of the cellular UPR by arenaviruses has recently been reported (Pasqual et al., 2011). Since an ERGIC-53 deficiency does not perturb the overall structure and function of the secretory pathway (Mitrovic et al., 2008), the virus-induced changes in ERGIC-53 trafficking appear as rather subtle alternations in the host cell.

The data at hand indicate a crucial role of ERGIC-53 present in the virion membrane for viral cell entry, whereas cellular ERGIC-53 seems dispensable. A hallmark of arenaviruses is the selective incorporation of processed mature GP into nascent virions (Lenz et al., 2001). Since ERGIC-53 associates specifically with GP precursors, a direct interaction of ERGIC-53 and mature GP at the level of the virion membrane appears rather unlikely. It will therefore be of great interest to dissect the exact role of ERGIC-53 during the viral entry process. As proposed by Klaus et al. (2013), ERGIC-53 may function as a structural component of the virion, perhaps by acting as a coreceptor required for virion attachment. The requirement of ERGIC-53 for infectivity of arenaviruses, coronaviruses, and filoviruses would suggest a coreceptor function in the context of a wide range of cellular receptors and target cells. Since receptor-mediated viral entry is a complex process, the identification of the specific entry step(s) that depend on ERGIC-53 will be crucial. Suitable quantitative assays to discern effects on virus-cell binding from endocytosis and/or viral fusion have been developed for many viral systems of interest. Alternatively, ERGIC-53 may affect virus-cell attachment indirectly by altering the oligomerization and/or geometry of GP at the virion surface. Defining the specific steps requiring ERGIC-53 may then facilitate a search for viral and cellular binding partners involved in the process. This will provide deeper insight into the mechanistic basis of the role of ERGIC-53 in productive virus infection and shed light on evolutionary conservation across virus families.

Apart from its obvious interest from a basic science point of view, ERGIC-53 also appears as an attractive cellular target for therapeutic intervention. Humans bearing null mutations in ERGIC-53 manifest with F5F8D, a relatively mild disease (Neerman-Arbez et al., 1999), suggesting that targeting this cellular factor in a therapeutic approach may have limited side effects. Additionally, the characterization of the viral GP-ERGIC-53 interaction performed by Klaus et al. (2013) indicates differential recognition of cellular cargo and viral GPs. It is conceivable that small-molecule screens for inhibitors of ERGIC-53-GP binding may yield candidate compounds that can perturb GP binding with lesser effects on cellular cargo. Considering the conservation of ERGIC-53 binding to a wide range of viral GPs, such candidate inhibitors may show broad antiviral activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grant FN310030_132844 and FN31003A_135536.

References

- Appenzeller-Herzog C., Hauri H.P. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2173–2183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itin C., Roche A.C., Monsigny M., Hauri H.P. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:483–493. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger S., Cimermancic P., Gulbahce N., Johnson J.R., McGovern K.E., Clarke S.C., Shales M., Mercenne G., Pache L., Li K. Nature. 2012;481:365–370. doi: 10.1038/nature10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus J.P., Eisenhauer P., Russo J., Mason A., Do D., King B., Taatjes D., Cornillez-Ty C., Boyson J.E., Thali M. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:522–534. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.010. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz O., ter Meulen J., Klenk H.D., Seidah N.G., Garten W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:12701–12705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221447598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovic S., Ben-Tekaya H., Koegler E., Gruenberg J., Hauri H.P. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:1976–1990. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-0989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neerman-Arbez M., Johnson K.M., Morris M.A., McVey J.H., Peyvandi F., Nichols W.C., Ginsburg D., Rossier C., Antonarakis S.E., Tuddenham E.G. Blood. 1999;93:2253–2260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyfeler B., Nufer O., Matsui T., Mori K., Hauri H.P. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;304:599–604. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00634-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqual G., Burri D.J., Pasquato A., de la Torre J.C., Kunz S. J. Virol. 2011;85:1662–1670. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer A., Fransen J.A., Bächi T., Ginsel L., Hauri H.P. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:1643–1653. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]