Summary

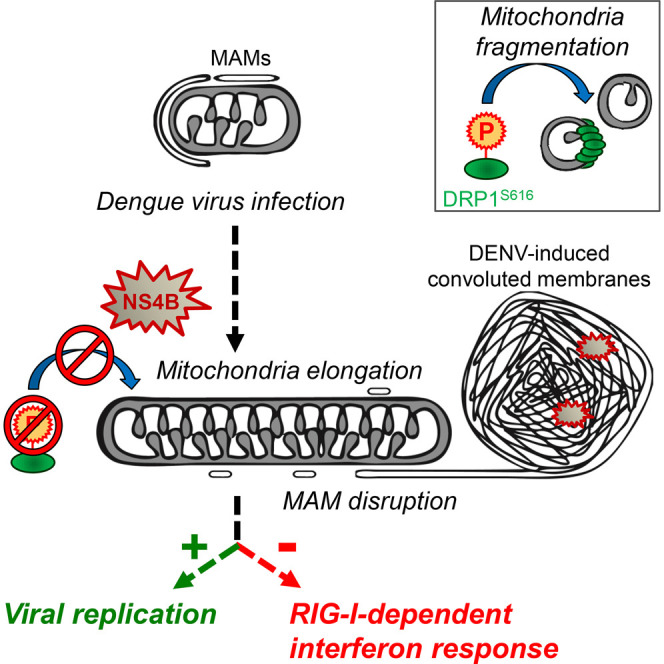

With no antiviral drugs or widely available vaccines, Dengue virus (DENV) constitutes a public health concern. DENV replicates at ER-derived cytoplasmic structures that include substructures called convoluted membranes (CMs); however, the purpose of these membrane alterations remains unclear. We determine that DENV nonstructural protein (NS)4B, a promising drug target with unknown function, associates with mitochondrial proteins and alters mitochondria morphology to promote infection. During infection, NS4B induces elongation of mitochondria, which physically contact CMs. This restructuring compromises the integrity of mitochondria-associated membranes, sites of ER-mitochondria interface critical for innate immune signaling. The spatio-temporal parameters of CM biogenesis and mitochondria elongation are linked to loss of activation of the fission factor Dynamin-Related Protein-1. Mitochondria elongation promotes DENV replication and alleviates RIG-I-dependent activation of interferon responses. As Zika virus infection induces similar mitochondria elongation, this perturbation may protect DENV and related viruses from innate immunity and create a favorable replicative environment.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

DENV NS4B induces mitochondria elongation during viral infection

-

•

Elongated mitochondria and virus-induced convoluted membranes are physically linked

-

•

NS4B inhibits activation of the mitochondrial fission factor DRP1

-

•

Mitochondria elongation alleviates DENV-induced RIG-I-dependent innate immunity

Chatel-Chaix et al. show that during Dengue virus infection, the viral protein NS4B induces mitochondrial elongation by inactivating the fission factor DRP1. Elongated mitochondria make physical contacts with virus-induced replication factories while mitochondria-associated membranes are altered. Importantly, mitochondria elongation dampens the early interferon response in favor of virus replication.

Introduction

Dengue virus (DENV) infection causes the most prevalent arthropod-born viral disease, with an estimated 100 million symptomatic cases per year worldwide, constituting a major unmet medical need. Antiviral drugs are not available, and a vaccine is approved only in a limited number of countries and is not applicable for people at highest risk (namely, young children and the elderly). Around one million DENV-infected individuals develop severe symptoms leading to hemorrhagic fever, shock syndrome and eventually death (Bhatt et al., 2013, World Health Organization., 2009).

DENV is a plus-strand RNA virus belonging to the Flavivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family. Upon entry into the host cell, the released viral genome is translated at the rough ER, generating a single polyprotein that is processed by host and viral proteases into ten proteins. While the structural proteins Capsid, prM, and Envelope assemble together with the RNA genome into new virus particles, the nonstructural proteins NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 are responsible for the replication of the viral genome. This replication takes place within virus-induced organelle-like cytoplasmic structures called replication factories (Acosta et al., 2014, Chatel-Chaix and Bartenschlager, 2014). These ER-derived membranous compartments consist of three substructures: (1) vesicle packets (VPs), formed by invagination of the ER membrane and believed to be the site of RNA replication; (2) virus “bags” in which virions accumulate most often in regular arrays; (3) convoluted membranes (CMs) that form by an unknown process (Welsch et al., 2009). Owing to the enrichment of NS3 in CMs, they are considered to play a role in polyprotein maturation (Welsch et al., 2009, Westaway et al., 1997). However, DENV RNA translation occurs at the rough ER where (co-translational) polyprotein cleavage occurs, arguing that CMs most likely play additional role(s). While there is evidence that NS4A is able to induce CMs to some extent (Miller et al., 2007), other DENV proteins, such as NS3 or NS4B, might contribute to this process. In addition to this ER remodeling activity, DENV proteins were also shown to interfere with specialized cellular processes in order to create an environment favorable to viral RNA replication. This includes a role of NS4A in autophagy (McLean et al., 2011) and modulation of RNAi, as well as innate immunity signaling by NS4B (Dalrymple et al., 2015, Kakumani et al., 2013, Muñoz-Jordan et al., 2003, Muñoz-Jordán et al., 2005). However, no functional link between these co-opting activities and the viral replication factories has been established so far.

The functions of NS4B might be of particular clinical relevance since this DENV protein has been identified as target of several antiviral compounds, some of which are currently in preclinical development (reviewed in Xie et al., 2015). To gain more insight into NS4B function(s) during DENV infection, we determined the NS4B-specific host interactome in infected cells and identified several mitochondrial components. We show that DENV infection perturbs mitochondrial morphodynamics by inducing mitochondria elongation at the vicinity of NS3- and NS4B-containing CMs. Elongation is induced by NS4B and mediated by inactivation of the mitochondrial fission factor Dynamin-Related Protein-1 (DRP1). Importantly, mitochondria elongation favors DENV replication and dampens activation of the interferon response.

Results

DENV Infection Induces Mitochondrial Elongation

With the aim to discover functions of NS4B, we elucidated the host interactome of NS4B in DENV-infected cells by taking advantage of a previously reported DENV2 16681 (DVs) strain that expresses a fully functional HA-tagged NS4B (Figure S1A) (Chatel-Chaix et al., 2015). NS4B-HA∗-associated proteins were efficiently co-purified from infected Huh7 hepatoma cells (Figures S1B and S1C) and identified using mass spectrometry (Figure S1D; Table S1). Based on three independent preparations, 19 host proteins were significantly enriched with NS4B-HA∗ and very strikingly, 12 of these hits were mitochondrial proteins. Among those, ATP synthase β subunit (ATP5B), monoamine oxidase B (MAOB), and voltage-dependent anion channel 2 (VDAC2) were validated as NS4B interaction partners (Figure S1E), arguing for an association between NS4B and mitochondria.

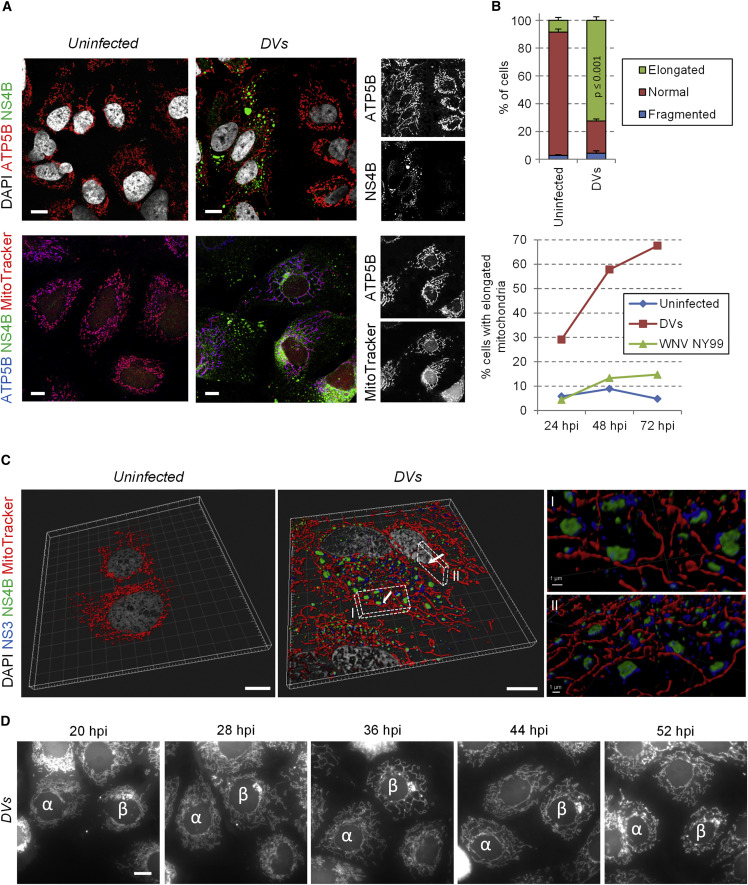

Immunofluorescence-based labeling of these host cell proteins combined with whole mitochondria staining using MitoTracker revealed that the morphology of mitochondria drastically changed in DVs-infected cells (Figures 1A and 1B; Figure S1F). Indeed, as confirmed by confocal microscopy-based 3D reconstruction of DENV-infected cells (Figure 1C; Movie S1), mitochondria were elongated and frequently in physical contacts with punctate structures that contained both NS3 and NS4B but not the replication intermediate double strand (ds)RNA (Figure S2A), suggesting that these structures are not vesicle packets, the presumed site of viral RNA replication. The same elongation phenotype was observed with another DENV2 strain, New Guinea C (NGC), with DENV of other serotypes (1, 3, and 4) and with two strains of the closely related Zika virus (ZIKV; H/PF/2013 and MR766, belonging to the Asian and the African lineage, respectively) (Figures S2B–S2G and S2J). In contrast, no such alteration was observed in cells infected with other Flaviviridae members, namely the flavivirus West Nile virus (WNV) and the hepacivirus hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Figure 1B; Figures S2H–S2J), arguing that this phenotype is specific to DENV and ZIKV.

Figure 1.

DENV Infection Induces Mitochondria Elongation

(A) Huh7 cells were infected with the DENV2 strain 16681 (DVs) at MOI = 1 or left uninfected. Three days later, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and indicated proteins were visualized by immunofluorescence using confocal microscopy. Incubation with MitoTracker was performed right before fixation.

(B) Quantification of immunofluorescence shown in (A). Upper panel: the mitochondrial network of ∼100 cells per condition and experiment (n = 4) was examined and classified into three morphological categories (normal, fragmented, elongated). Lower panel: the morphology of the mitochondrial network was analyzed in uninfected, DVs- or WNV-infected cells at 1, 2, and 3 days post infection. Error bars indicate SEM calculated using four independent experiments.

(C) Upon optical sectioning and deconvolution, Z-stacks were used for 3D reconstruction of control and DVs-infected cells stained for NS3, NS4B, and mitochondria. (I and II) Magnifications of regions of interest (indicated with white cuboids) show the proximity between NS3/NS4B-containing punctae and elongated mitochondria. The viewing angles are indicated with the white arrows in the cuboids.

(D) Live cell imaging frame captures of DVs-infected Huh7 cells (MOI = 10) expressing a mitochondria-targeted mTurquoise2 fluorophore. Captures were made 20, 28, 36, 44, and 52 hr post infection and show progressive elongation of mitochondria over time. To facilitate tracking, two cells of interest are labeled with α and β. Scale bar, 10 μm, except (CI) and (CII).

Next, we generated a Huh7 cell line expressing a mitochondria-targeted fluorophore (mito-mTurquoise2), allowing live cell imaging of mitochondrial morphodynamics. This cell line supported DENV replication comparably to the parental Huh7 cell line and recapitulated mitochondria morphology changes when analyzing fixed cells (Figures S3A and S3B). In living uninfected cells, the mitochondrial network was highly dynamic, and mitochondrial morphology alternated between moderate elongation and fragmentation (Figure S3C; Movie S2). In stark contrast, in DVs-infected cells, mitochondria elongation became first visible 23 hr after infection and was most pronounced between 35 and 50 hr post infection (Figure 1D; Movie S2). At very late time points after infection, the mitochondrial network collapsed concomitantly with cell death due to DENV-induced-cytopathic effects. Mitochondria elongation was also observed in DENV2 NGC-infected cells (Movie S3), but with a faster kinetic correlating with a higher replication capacity of this strain. These observations clearly demonstrate that DENV infection modulates mitochondrial morphodynamics.

Elongated Mitochondria and NS3/NS4B-Containing CMs Are Physically Linked

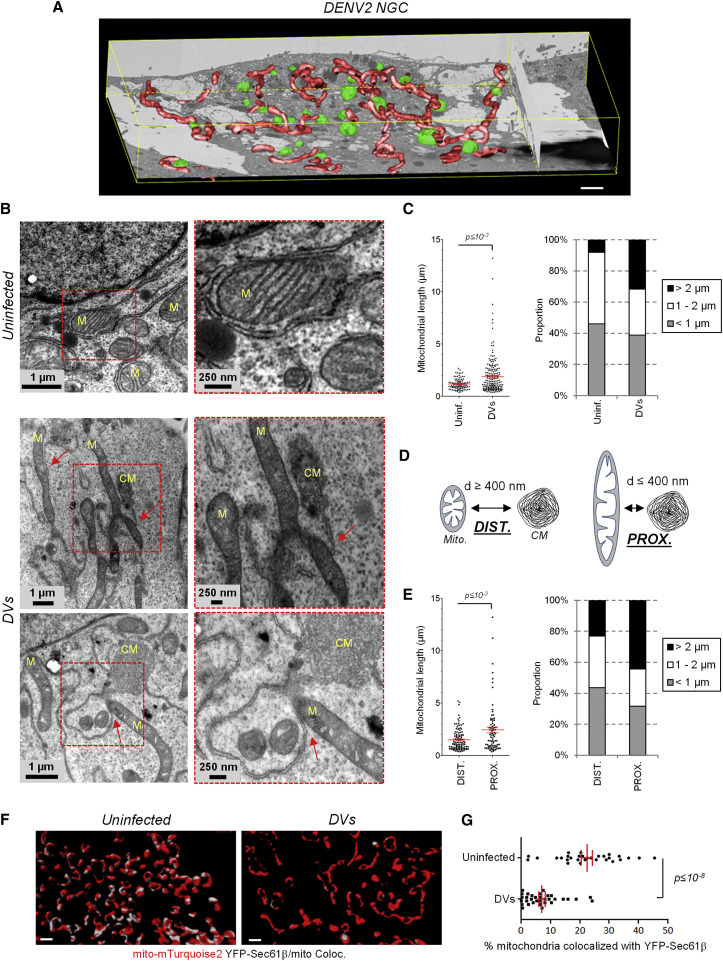

To characterize the ultrastructural details of elongated mitochondria in DENV-infected cells, we utilized automated serial imaging by focused ion beam–scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM). Three-dimensional reconstruction of most of the cell volume revealed a network of elongated mitochondria in both NGC- and DVs-infected cells, which was not found in uninfected cells (Figure 2 A; Figure S4A; Movie S4). Elongated mitochondria often localized in the vicinity of electron dense structures resembling convoluted membranes. Indeed, examination of ultrathin sections of infected cells at a higher resolution by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) confirmed that CM-proximal mitochondria were more elongated than CM-distal ones (Figure 2B–E). In contrast to uninfected cells in which mitochondria were found in contact with ER tubules called mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) (Vance, 2014), this interface was mostly disrupted in DENV-infected cells. Very strikingly, CMs appeared to be physically connected to mitochondria only at single sites arguing for a profound loss of the mitochondria–ER interface (Figure 2B; Figure S4B, red arrows).

Figure 2.

DENV2 Induces Mitochondria Elongation in the Vicinity of Viral Convoluted Membranes and Alters Mitochondria-ER Contacts

(A) Huh7 cells were infected with DENV2 NGC (MOI = 5). 24 hr later, cells were processed for FIB/SEM. Tridimensional reconstruction for mitochondria (red) and CM (green) was performed. Scale bar, 2 μm.

(B) Sections of control and DVs-infected cells were analyzed by TEM. Magnification of regions of interest, red squares) are given below each top panel to highlight that ER-mitochondria contacts sites are mostly disrupted. In addition, CMs are connected to mitochondria (M) at distinct sites via ER membranes (red arrows).

(C) The length of mitochondria was measured with the ImageJ software package using multiple images acquired by TEM; lengths were classified into three categories.

(D and E) Elongation of CM-proximal mitochondria. The distance between mitochondria and CMs (d) was measured. When this distance was below or above 400 nm, a given mitochondria was considered proximal (PROX.) or distal (DIST.), respectively. Mitochondria lengths (y axis) of these two groups are shown and were classified as in (C). Further examples of EM images are given in Figure S4B.

(F) Huh7/mito-mTurquoise2/YFP-Sec61β cells were left uninfected or infected with DVs. Three days later, cells were fixed and stained for NS3 (not shown). Optical sections were acquired with a spinning disc confocal microscope and after deconvolution, Z-stacks were used for 3D reconstruction and 3D colocalization analysis between mitochondria and YFP-Sec61β-containing ER networks. Note that NS3-positive cells were considered infected. White areas on reconstructed mitochondria indicate sites of colocalization with YFP-Sec61β (Coloc.). Scale bar, 1 μm.

(G) A 3D colocalization analysis quantifying the extent of mitochondria/Sec61β contacts in uninfected (n = 30) and DVs-infected cells (n = 33).

To further confirm this DENV-mediated alteration of the ER–mitochondria interface at the whole cell level, we generated a Huh7 cell line stably expressing mito-mTurquoise2 and a fluorescent ER marker (YFP-Sec61β). This allowed us to identify ER-mitochondria contact sites using confocal microscopy as previously described (Friedman et al., 2011). DENV replicated efficiently in this cell line and induced mitochondria elongation (Figures S3D and S3E). Use of 3D co-localization analysis following reconstruction of mitochondria and Sec61β-positive ER networks showed that the extent of contacts between these two compartments was significantly altered in DENV-infected cells (Figures 2F and 2G; Figures S5A and S5B), arguing that DENV profoundly altered the MAMs.

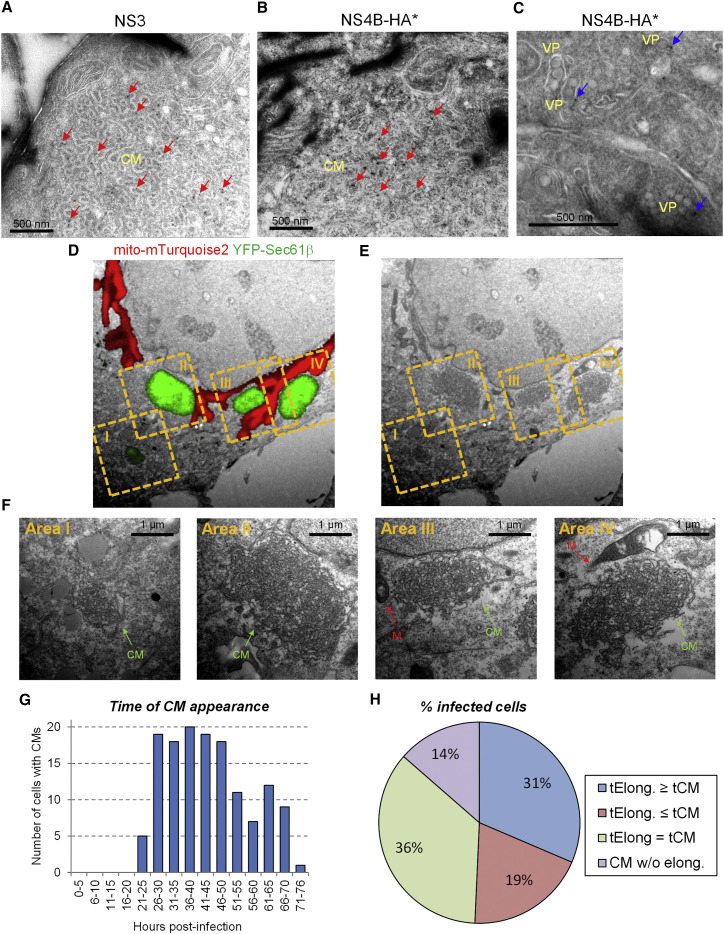

Interestingly, Sec61β accumulated in infected cells in NS3-positive large structures (Figure S3E, right panel) corresponding to the dsRNA-free NS3/NS4B-containing punctae described in Figures 1C and S2A. Therefore, we hypothesized that these mitochondria-connected puncta might be CMs. We evaluated this assumption in several ways. First, we used TEM of immunolabeled thawed cryosections of DVs-infected cells and confirmed that CMs contained both NS3 (as previously reported by Welsch et al., 2009) and a fraction of NS4B (Figures 3 A–3C). Second, we applied correlative light-electron microscopy (CLEM) of DENV-infected cells using the Huh7/mito-mTurquoise2/YFP-Sec61β cell line previously described. Importantly, by using YFP-Sec61β as an indirect marker of NS3/NS4B-containing puncta to perform CLEM with nonpermeabilized cells, the YFP-Sec61β fluorescent signal perfectly correlated with CMs detected by TEM, but not with VPs (Figures 3D–3F; Figures S5C–S5E). This result unambiguously identified the puncta containing both NS3 and NS4B, but devoid of dsRNA as DENV-induced CMs.

Figure 3.

CMs Contain Both NS4B and NS3, and Their Biogenesis Is Linked in Time and Space with Mitochondria Elongation in DENV-Infected Cells

(A–C) Huh7 cells were infected with DVs(NS4B-HA∗). Three days post infection, cells were processed for immunolabeling of thawed cryosections using NS3- or HA-specific primary antibodies to detect NS3 (A) or NS4B-HA∗ (B and C), respectively. Red arrows: immune-gold-labeled NS3 (A) or NS4B-HA∗ (B) within DENV-induced CMs. Blue arrows: immune-gold-labeled NS4B-HA∗ (C) associated with VPs.

(D–F) Huh7/mito-mTurquoise2/YFP-Sec61β cells were infected with DVs and processed for CLEM three days post infection. The mitochondria signal and NS3/NS4B-containing YFP-Sec61β puncta are shown in red and green, respectively. Mitochondria morphologies were used to allocate the red fluorescent signal of a Z-stack to the proper ultrastructure of the EM image and hence, for overall correlation. Regions of interest, yellow dashed squares, were selected for higher magnification analyses that are shown in (F).

(G and H) Huh7/mito-mTurquoise2/YFP-Sec61β cells were infected with DVs (MOI = 10) and analyzed by live-cell imaging. For 140 cells from 13 movies, the time of first appearance of CMs was determined (G) and correlated with the time when a given mitochondrial network started to elongate. Cells in which YFP-Sec61β accumulated within puncta were considered infected with DENV. (H) Infected cells were classified into four defined categories: tElong. ≥ tCM: Mitochondria elongation occurred after CM appearance; tElong. ≤ tCM: CM appeared after mitochondria elongation; tElong. = tCM. The two processes occurred simultaneously. CM w/o elong.: CM formation without detectable mitochondria elongation.

Taking advantage of this Huh7/mito-mTurquoise2/YFP-Sec61β cell line, we characterized the spatiotemporal relationship between mitochondria elongation and CM biogenesis by live-cell imaging of infected cells (Movies S5 and S6). Cells with CMs were detectable as early as 21 hr post infection and accumulated over time (Figure 3G). 86% of the cells with CMs also showed a network of elongated mitochondria (Figure 3H). Morphology of CMs was highly dynamic and merging as well as division of CMs was observed (Figure S6A; Movie S6). Notably, in 36% of infected cells (i.e., 42% of those also displaying elongated mitochondria) formation of CMs and mitochondria elongation occurred simultaneously. Moreover, contacts between these two compartments were readily detectable throughout the infection (Figure S6B). Taken together, these results suggest a spatio-temporal relationship between CM biogenesis and mitochondrial morphodynamics.

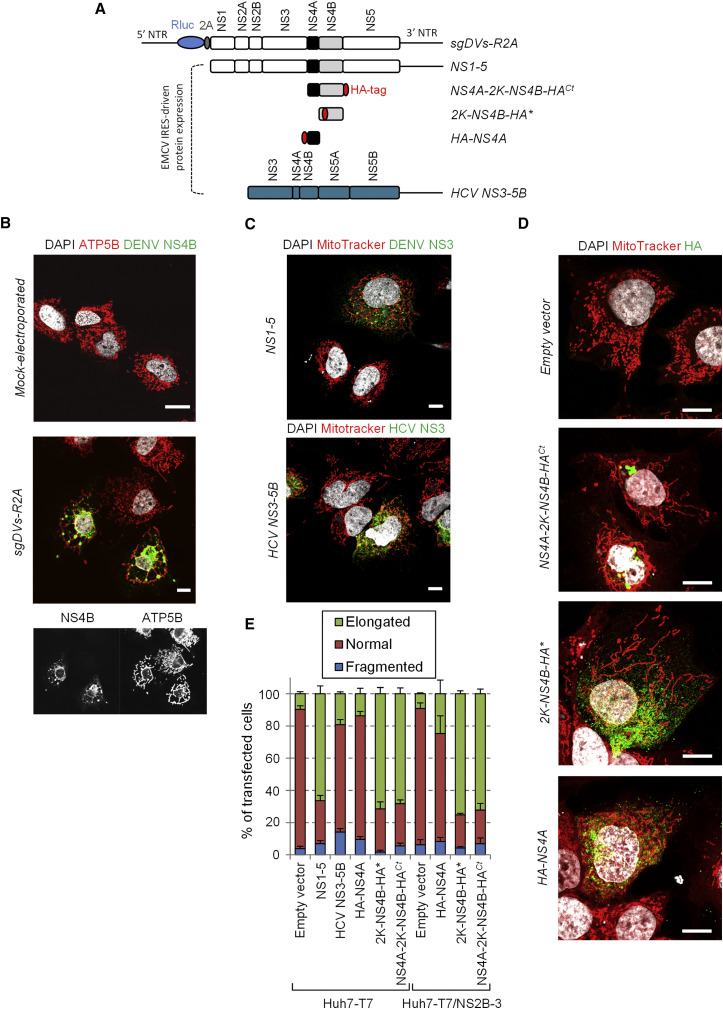

Expression of DENV NS4B Is Sufficient for Mitochondria Elongation

Next, we aimed at determining the DENV protein responsible for altering mitochondria morphodynamics. We used an expression-based approach (Figure 4 A) and took into account that DENV nonstructural proteins are sufficient for mitochondrial elongation, because we observed this phenotype in cells containing a DENV2 subgenomic replicon or expressing the NS1-5 polyprotein from a transfected plasmid (Figures 4B and 4C). Because several mitochondrial proteins were identified in the NS4B interactome, we hypothesized that NS4B was responsible for mitochondria elongation. Indeed, this phenotype was recapitulated when NS4B was expressed either as a NS4A-2K-NS4B precursor or as 2K-NS4B protein, with 2K serving as signal sequence for proper membrane insertion of NS4B (Figures 4D and 4E) (Chatel-Chaix et al., 2015). In contrast, individual expression of NS4A, NS2B-3, or the HCV NS3-5B polyprotein did not induce mitochondria elongation, demonstrating that this phenotype is specific to DENV NS4B (Figures 4C–4E).

Figure 4.

DENV2 NS4B Induces Mitochondria Elongation

(A) Schematic representation of used constructs. The subgenomic replicon is depicted in the top. The constructs used for expression with the T7-based system are indicated below. Black lines represent the DENV and HCV untranslated regions (NTRs). The HA-tag is shown as red oval.

(B) Huh7 cells were electroporated with capped in vitro transcripts of a sub-genomic RNA. Three days later, cells were processed for detection of ATP5B and DENV NS4B by immunofluorescence using confocal microscopy.

(C and D) Huh7 cells stably expressing T7 RNA polymerase only (Huh7-T7) (C and D) or T7 RNA polymerase and DENV NS2B-3 (Huh7-T7/NS2B-3) (not shown) were transfected with the expression constructs specified in the left of each panel. 24 hr later, cells were incubated with MitoTracker, fixed, immunostained for the indicated proteins and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Based on the analysis of mitochondria morphology of at least 150 cells per condition and at least three independent experiments, cells were classified into three groups as follows: elongated, normal and fragmented mitochondrial network. Error bars indicate SEM calculated using three or four independent experiments.

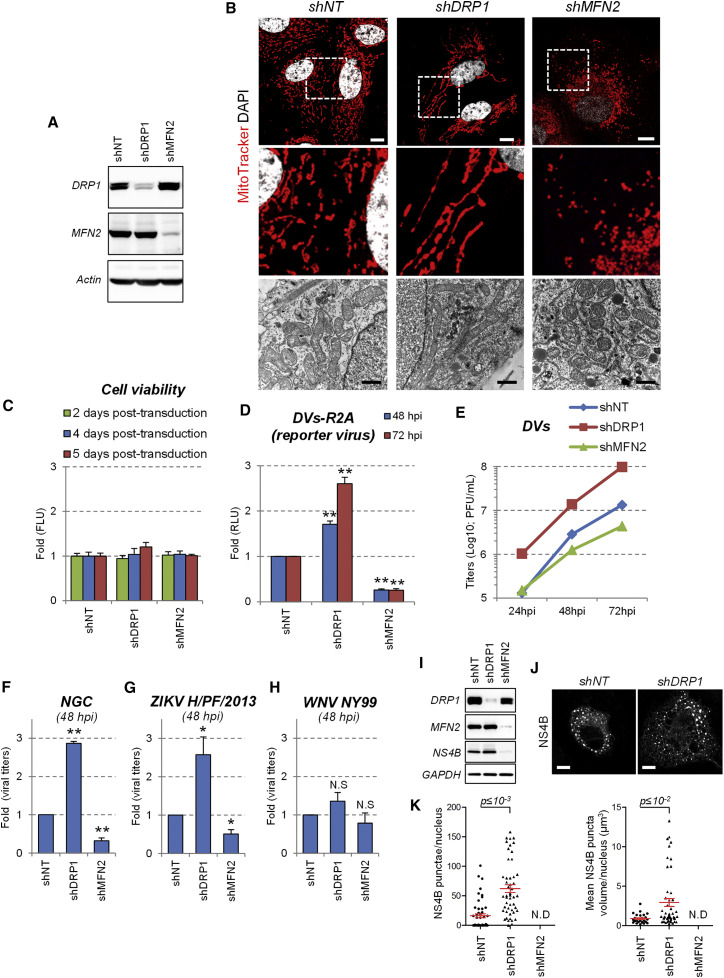

Mitochondria Elongation Favors DENV Replication

Mitochondria morphology is highly dynamic and relies on a fine-tuned equilibrium between fusion and fission leading to elongation and fragmentation, respectively. These processes are controlled by fusion factors (e.g., optic atrophy 1 [OPA1] and the mitofusins MFN2 and MFN1), as well as by fission factors (e.g., DRP1 and mitochondrial fission factor [MFF]) (Smirnova et al., 2001, Smirnova et al., 1998, Otera et al., 2010, Chen et al., 2003, Olichon et al., 2003). While mitochondria-resident proteins MFN and OPA1 localize on the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes, respectively, and promote interorganelle membrane fusion, DRP1 is primarily cytosolic and translocated to mitochondria to mediate fragmentation via its dynamin-related activity (Chan, 2012). This fusion/fission equilibrium can be influenced by modulating the expression of these factors. Indeed, RNAi-mediated knockdown of DRP1 stimulated mitochondria elongation, whereas decreased MFN2 expression favored their fragmentation (Figures 5A and 5B) without affecting cell viability during a 5-day observation period (Figure 5C). Importantly, DRP1 knockdown-mediated elongation stimulated replication of both DENV strains DVs and NGC (Figures 5D–5F), whereas MFN2 knockdown-enforced mitochondria fragmentation inhibited DENV replication. Interestingly, the replication of ZIKV, which also induced mitochondria elongation, was stimulated by DRP1 knockdown as well (Figures 5G and S6C), whereas replication of WNV and HCV remained unaffected under these conditions (Figures 5H and S6C). These results show that mitochondria elongation favors DENV and ZIKV replication.

Figure 5.

Mitochondria Elongation Favors DENV Replication

(A) Huh7 cells were transduced with shRNA-expressing lentiviruses. Four days post transduction, cells were collected and the expression of both DRP1 and MFN2 was analyzed by western blotting.

(B) The morphology of mitochondria in shRNA-transduced cells was analyzed by confocal microscopy after staining with MitoTracker or by TEM (lower panels). White scale bar, 10 μm; black scale bar, 1 μm.

(C) Cell viability of transduced cells was evaluated 2, 4, or 5 days post-transduction using the CellTiter-Glo assay, which is a measure for ATP levels in the cells.

(D–F) Two days post transduction, cells were infected with (D) the DVs-R2A reporter virus (MOI = 0.1), (E) DVs (MOI = 0.01), (F) NGC (MOI = 0.01).

(G) ZIKV H/PF/2013 (MOI = 0.05) or (H) WNV NY99 (MOI = 0.05). At the indicated time points, Renilla luciferase activity (RLU) reflecting DENV RNA replication (D) or virus titers (E–H) were determined. Mean values and SD are indicated in (C) displaying a representative of at least three independent replicates. Mean values and SEM are indicated in (C) and (F)–(H) based on at least three independent experiments. ∗∗p ≤ 10−3; ∗p ≤ 10−2; N.S: not significant (p ≥ 0.05).

(I) Huh7-T7 cells were transduced with shRNA-expressing lentiviruses and transfected three days post transduction with a plasmid encoding a DENV2 NS1-5 polyprotein. 16 hr later, cells were analyzed for knockdown efficiency and NS4B expression using western blotting.

(J) Cells from (I) were fixed, permeabilized and NS4B was visualized by immunofluorescence using confocal microscopy.

(K) Optical sections were acquired for 50 cells in two independent experiments and, after 3D reconstruction, number and mean volume of NS4B punctae per cell were determined.

To directly address the impact of enforced mitochondrial morphodynamics on CM morphogenesis, we exploited a NS1-5 polyprotein-based expression system to study the impact of DRP1 or MFN2 knockdown on frequency and size of NS4B punctae independent from viral replication (Figures 5I–5K). Enforced mitochondria elongation by silencing DRP1 expression increased the number and volume of NS4B-containing clusters whereas in cells with MFN2 knockdown no NS4B-positive clusters (and hence, CMs) could be detected. Interestingly, rapid induction of mitochondria fragmentation via CCCP-mediated depolarization resulted in a loss of NS4B-containing CMs (Figure S7A). Altogether, these data support the notion that mitochondria morphology directly influences the biogenesis or stability of CMs.

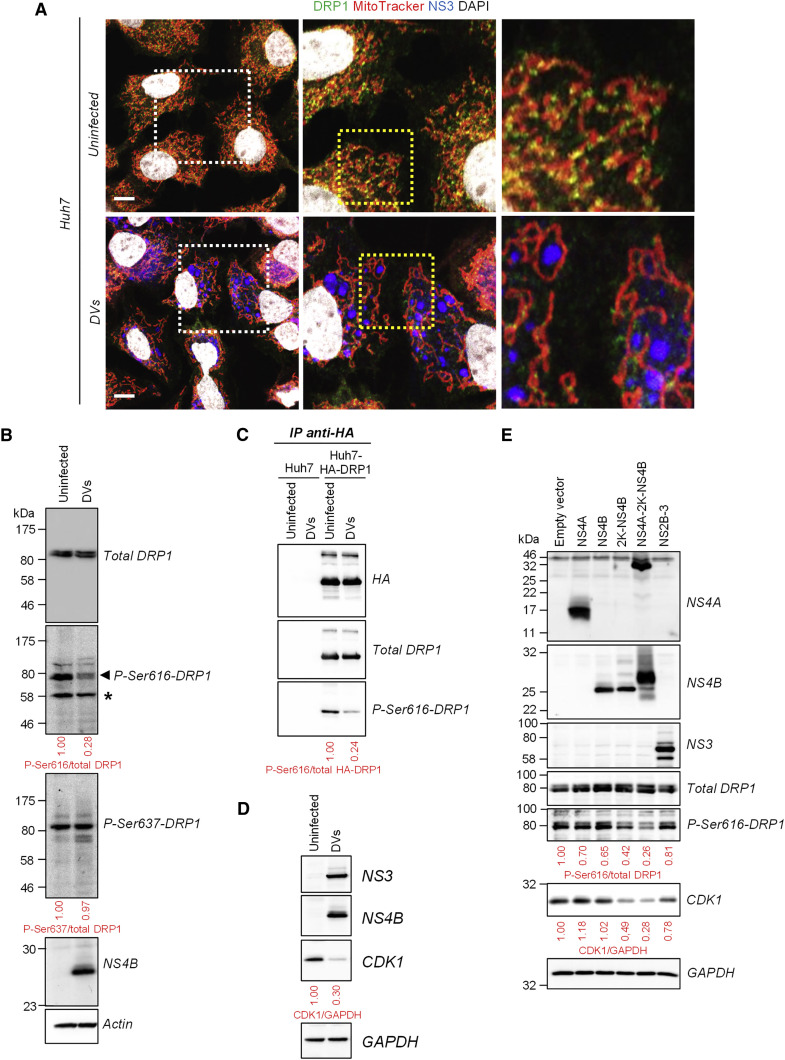

DENV NS4B Inhibits DRP1 Activation

We next sought to determine the molecular mechanism underlying DENV-induced mitochondria elongation. In the first set of experiments, we determined the stoichiometries between DRP1 and the fusion factors MFN1, MFN2 and OPA1. Their expression levels remained unchanged upon DENV2 infection (Figure S7B) and hence, alterations in their relative abundance could not account for DENV-induced mitochondria elongation. In uninfected cells, DRP1 is detectable only as puncta localizing preferentially at the tip of daughter mitochondria, reflecting DRP1 oligomers mediating or having resolved the fission of a mitochondrion (Figure 6 A; Figure S7C) (Strack and Cribbs, 2012). Importantly, in cells infected with DVs or NGC, mitochondria-associated DRP1 levels decreased (Figures 6A and S7D, respectively), suggesting that DRP1 translocation to mitochondria and hence, their fragmentation is altered.

Figure 6.

DENV2 Inhibits the Activation and Mitochondrial Translocation of the Fission Factor DRP1

(A) Huh7 cells were infected with DVs (MOI = 1). Three days post infection, cells were labeled with MitoTracker, DAPI and antibodies specified on the top. Dotted boxes indicate areas that are enlarged in the respective adjacent panel. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(B) Extracts of naive or DVs-infected cells were prepared 72 hr after infection and analyzed by western blotting using antibodies recognizing differentially phosphorylated (Ser616 or Ser637) or total DRP1. ∗Non-specific band.

(C) Extracts of Huh7 and HA-DRP1-overexpressing Huh7 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation using an HA-specific antibody. Captured complexes were analyzed by western blotting for phosphorylated and total DRP1.

(D) Cell lysates were prepared as in (B) and analyzed by western blotting.

(E) Huh7 cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing the indicated DENV proteins (MOI = 5). Four days later, cell extracts were prepared and analyzed for the expression of the indicated proteins using western blotting.

Since serine phosphorylation of DRP1 at residues 616 and 637 can stimulate and repress DRP1 fission activity, respectively (reviewed in Chan, 2012, Lee and Yoon, 2014), we evaluated whether DENV infection influences DRP1 phosphorylation status. While phosphorylation of Ser637 remained unaffected during infection, the level of DRP1 phosphorylated at serine residue 616 decreased in DENV-infected cells for both endogenous and overexpressed DRP1 (Figures 6B–6C and S7E). Ser616 of DRP1 was previously reported to be phosphorylated by several kinases, namely CDK1, CDK5, and ERK1/2 (Lee and Yoon, 2014, Chan, 2012). Strikingly, CDK1 expression decreased in DENV-infected cells (Figure 6D) while the levels of activated ERK1/2 and CDK5 remained unchanged during DENV infection (Figure S7E). Importantly, this phenotype was mediated by properly membrane-associated NS4B since the expression of either the NS4A-2K-NS4B precursor or 2K-NS4B alone was sufficient to decrease both P-Ser616-DRP1 and CDK1 levels, which was not the case with NS4B lacking the 2K signal sequence (Figure 6E). These results demonstrate that DENV inhibits phospho-S616-dependent activation of DRP1 and its subsequent translocation to mitochondria, thus perturbing the fusion/fission equilibrium. This result provides an explanation for mitochondria elongation in virus-infected cells.

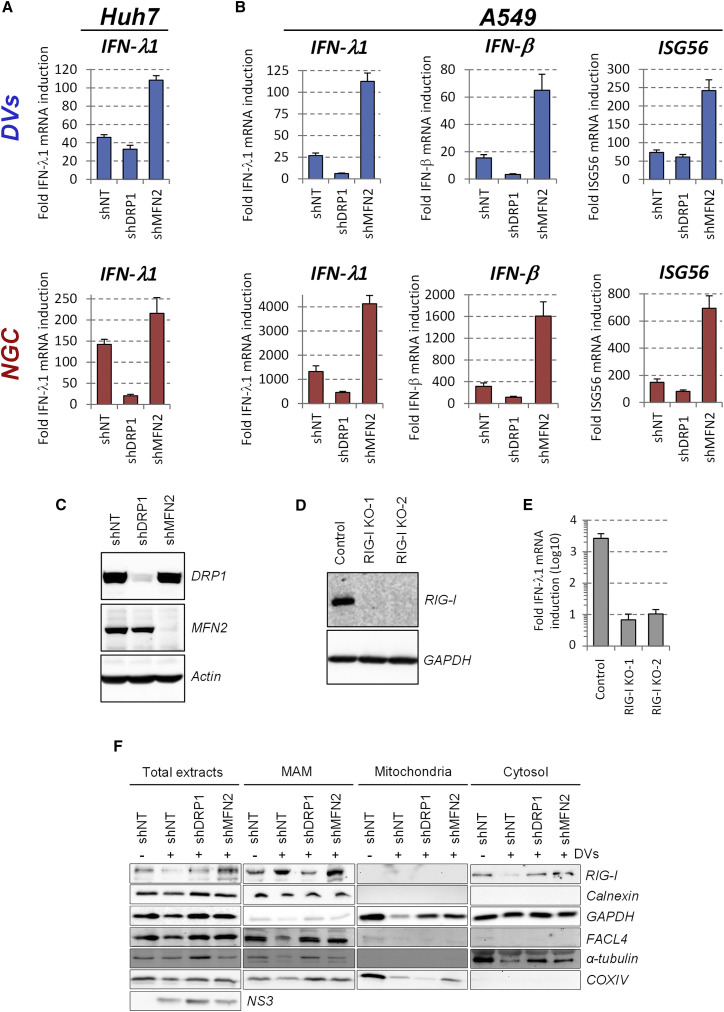

Mitochondria Elongation Alleviates DENV-Induced Innate Immunity

The ER–mitochondria interface serves as platform for MAVS-dependent innate signaling through the recruitment of activated cytosolic RNA sensors RIG-I and MDA5 (Horner et al., 2011). In the light of the altered ER-mitochondria contact sites, indicative of MAMs, we reasoned that the virus might induce mitochondrial changes in DENV-infected cells to suppress the activation of the innate antiviral response. Hence, we evaluated the impact of mitochondria morphology on DENV-induced interferon (IFN) induction. When elongation was favored by knockdown of DRP1 expression in Huh7 cells, the induction of endogenous IFN-λ1 expression markedly decreased, best visible with the DENV2 NGC strain (Figure 7 A), consistent with the increase of virus titer (Figures 5E and 5F). In contrast, knockdown of MFN2 expression induced mitochondria fragmentation and enhanced the expression of IFN-λ1 (Figure 7A), which correlated with the impaired DENV replication (Figures 5E and 5F). The analogous result was obtained when monitoring IFN-λ1, IFN-β and ISG56 expression in A549 cells (Figure 7B), which are more competent especially with respect to IFN-β production. Interestingly, knockout of RIG-I in Huh7 cells by CRISPR/Cas9 technology suppressed DENV-induced IFN-λ1 production ∼100-fold (Figures 7D and 7E), showing that RIG-I-dependent signaling is responsible for most of DENV-induced innate immune response.

Figure 7.

Mitochondria Elongation Alleviates DENV2-Induced Activation of the Interferon Response

Huh7 and A549 cells were transduced with DRP1- or MFN2-specific shRNA-encoding lentiviruses. Two (Huh7) or three (A549) days post-transduction, cells were infected with DENV2 DVs or NGC (MOI = 5).

(A and B) 48 (Huh7) or 24 (A549) hr later, cells were collected and mRNA amounts of IFN-λ1, IFN-β, and ISG56 were quantified using qRT-PCR. Quantifications are representative of three independent replicates.

(C) Knockdown efficiency in A549 cells was monitored 4 days post transduction by western blotting using MFN2- and DRP1-specific antibodies. Actin served as loading control.

(D) Huh7 RIG-I knockout cell pools were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 technology using two different guide RNAs and lysates of cells were analyzed by western blotting.

(E) RIG-I knockout cells were infected with DVs or left uninfected. Two days later, abundance of IFN- λ1 and β-actin mRNA was measured using qRT-PCR. IFN- λ1 induction levels upon infection were calculated after normalization to β-actin. For qRT-PCR experiments (A, B, E), error bars indicate SD calculated using three technical replicates.

(F) Huh7 cells were transduced and infected with DVs as in (A). Cell extracts were subjected to subcellular fractionation to isolate MAMs. Equal amounts of proteins from each fraction were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies recognizing the indicated proteins. FACL4 and calnexin served as markers enriched in the MAM fraction and α-tubulin as cytosolic marker.

Considering the links among MAMs, CMs, and elongated mitochondria, we hypothesized that mitochondria elongation might impair DENV-induced RIG-I translocation to MAMs, thus dampening innate immunity. We altered mitochondria morphology by knockdown of DRP1 and MFN2 and isolated MAMs by subcellular fractionation. Upon knockdown of DRP1 expression, the abundance of RIG-1 in the MAM fraction was drastically decreased, concomitant with an accumulation in the cytosolic fraction (Figure 7F) and consistent with a reduced innate immune signaling (Figure 7A). Consistently, the opposite phenotype was observed upon silencing of MFN2 expression. Overall, these data demonstrate that mitochondria elongation alleviates DENV-induced RIG-I-dependent innate immunity and further suggest that DENV-induced mitochondria elongation confers a protective effect against these antiviral responses.

Discussion

It is well established that all plus-strand RNA viruses induce membranous replication factories (Paul and Bartenschlager, 2013), but the impact of these factories on morphology and function of cellular organelles remains largely unknown. Here, we show that DENV—via NS4B—induces mitochondria elongation as a result of fragmentation inhibition. This was due to suppressed phosphorylation-dependent activation of DRP1 and impaired translocation to mitochondria, which, however, is required to trigger fission via the dynamin-related activity residing in DRP1. The sole expression of 2K-NS4B is sufficient to downregulate CDK1, a kinase contributing to DRP1 phosphorylation at Ser616; this is consistent with the observed induction of mitochondria elongation by this viral protein. Since CDK1 (in complex with cyclin B) is primarily active during mitosis, NS4B might inhibit DRP1 phosphorylation predominantly during this phase of the cell cycle. In this case, the alteration of mitochondria morphology during interphase as observed here would be triggered during mitosis and last for extended periods thereafter.

By using a replication-independent DENV NS1-5 polyprotein expression system, we provide evidence that mitochondria morphology directly influences NS4B large puncta, reminiscent of CMs (Figures 5J and 5K). Consistently, rapid induction of mitochondria fragmentation by CCCP treatment led to the disappearance of NS4B-containing CMs (Figure S7A), supporting the notion that mitochondria morphology is important for CM biogenesis and/or maintenance. However, CMs were not detected in cells expressing only 2K-NS4B (M.C., L.C.-C., and R.B., unpublished data), arguing that CMs are not absolutely required for mitochondria elongation and that CM biogenesis requires additional viral factors, such as NS4A (Miller et al., 2007).

Several reports showed that DRP1 translocation to mitochondria depends on prior actin-dependent constriction of mitochondria by juxtaposed ER tubules or, more precisely, MAMs (Friedman et al., 2011, Korobova et al., 2013, Manor et al., 2015). Considering that ER-mitochondria contacts are partly disrupted in DENV-infected cells, we hypothesize that CMs also contribute to the disappearance of pre-constricting ER and hence, to the loss of DRP1 translocation and mitochondria fission. Hence, the observed mitochondria elongation most probably results from a combination of NS4B-dependent inactivation of DRP1 and MAM disruption that appears to be linked to CM biogenesis. However, we cannot exclude that the fusion machinery might be modulated by DENV as well, e.g., by altering MFN proteins (Pyakurel et al., 2015, Chen and Dorn, 2013, Glauser et al., 2011, Leboucher et al., 2012, Ziviani et al., 2010). Very recently, Yu and colleagues proposed that DENV infection inhibits fusion activity of mitofusin proteins (Yu et al., 2015). Although we never detected MFN1 or MFN2 cleavage in DENV-infected cells, we note that the conclusions of Yu and coworkers were based on rather artificial experimental approaches, including heterokaryon formation and MFN overexpression-based mitochondria hyperfusion assays, and the impact of DENV on mitochondria fusion was evaluated during short timescales and after high virus-dose inoculation. Moreover, these authors used stable knockdown cell lines to silence MFN gene expression, which we avoided to limit the risk of selecting for cells compensating the fragmentation phenotype by alternative mechanisms to maintain the fusion/fission equilibrium. Moreover, Yu and colleagues did not directly address the impact of DENV on DRP1 function and on general mitochondria morphodynamics (e.g., by using mitochondria staining of naive cells infected with DENV). We note that Yu and colleagues did not report mitochondria fragmentation in DENV-infected cells, which would be expected in case of fusion inhibition; this demonstrates that the proposed impairment of fusion makes little, if any, contribution to the overall mitochondria morphology in infected cells. Some of the discrepancies might also be explained by different timing of analyses. While the DENV-induced elongation phenotype reported here is most obvious 48–72 hr post infection when CMs form, Yu and coworkers observed MFN function as early as 24 hr post infection.

The temporal analysis of CM biogenesis revealed that in 36% of infected cells, mitochondria elongation occurs simultaneously to the appearance of CMs. While these two phenomena are most probably not strictly interdependent, our data argue for a spatiotemporal coordination between these processes. Consistently, 86% of cells contained both elongated mitochondria and CMs that remained in close proximity throughout the course of infection.

During the last decade, the ER-mitochondria interface has emerged as a critical signaling platform for MAVS-dependent activation of the innate immune response (Horner et al., 2011, van Vliet et al., 2014). We show that mitochondria elongate during DENV infection, and ER-mitochondria contact sites are disrupted most probably by CM formation. In this way, ER membranes tightly surrounding mitochondria appear to be removed, thus impairing the recruitment of activated RIG-I to MAMs and protecting the virus from an antiviral state. While this is an interesting mechanism by which a virus escapes innate antiviral defense, DENV utilizes additional strategies. For instance, the DENV NS2B-3 protease, is highly enriched in CMs, proteolytically inactivates the MAM-resident signaling adaptor STING (Aguirre et al., 2012, Yu et al., 2012) and prevents RIG-I translocation to mitochondria by targeting the adaptor protein 14-3-3ε (Chan and Gack, 2016). Moreover, NS4B overexpression was found to impair the RIG-I/MDA5-dependent pathway at the level of TBK1/IKKε activation via an unknown process (Dalrymple et al., 2015). Given the central role of NS4B in mitochondria elongation as described here and its interaction with NS3 (Chatel-Chaix et al., 2015), the functional cross-talk between these two proteins for all these phenotypes will be an important task for future studies.

Despite conflicting reports about the role of mitofusins in IFN induction (Castanier et al., 2010, Onoguchi et al., 2010, Yasukawa et al., 2009, Yu et al., 2015), it was shown that mitochondria elongation increases ER-mitochondria contacts (as monitored by STING/MAVS interaction) and would hence, stimulate innate immune signaling (Castanier et al., 2010). Moreover, several studies support the idea that some viruses evade from innate immunity by inducing mitochondria fragmentation to disrupt MAVS-dependent signaling (Kim et al., 2014, Yoshizumi et al., 2014, Xia et al., 2014). In the present study, we rather observe that mitochondria elongation is proviral and alleviates type I and III IFN expression. This discrepancy might be due to the fact that DENV, by inducing CMs, disrupts MAMs and thus, an early IFN response. Reminiscent to DENV, Shi and colleagues reported that severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) ORF-9b protein induces mitochondria elongation through the proteasomal degradation of DRP1, and impairs innate immunity by targeting MAVS-dependent signaling (Shi et al., 2014). Of note, two independent studies by other groups showed that SARS-CoV also induces convoluted membranes (Knoops et al., 2008) and impairs STING-dependent signaling (Sun et al., 2012). In light of our results with DENV, one might speculate that SARS-CoV uses a similar “mitochondria-elongation” strategy to disrupt innate immunity. Although some molecular details about the link of mitochondria elongation and dampened IFN induction remain to be clarified, we propose that DENV NS4B induces mitochondria elongation to provide MAMs to NS4A, which stimulates CM biogenesis (Miller et al., 2007). Consequently, MAM-associated proteins, such as STING, would be hijacked and redirected to CMs. This accumulation of host factors in CMs may facilitate their cleavage by the NS2B-3 protease that is highly enriched in this compartment (Welsch et al., 2009). Whether such a DENV hijacking model could apply to additional MAM functions, such as autophagy, apoptosis, calcium transfer or ER-stress (van Vliet et al., 2014, Vance, 2014), remains to be determined.

Apart from NS4B-mediated alteration of DRP1 function, this or other DENV proteins might affect mitochondrial functions in alternative or perhaps complementary ways. For instance, our NS4B proteome identified many ATP synthase subunits, suggesting that DENV might alter local ATP production for the benefit of the biogenesis of membranous replication factories. Additionally, DENV might target VDAC2, also identified in our NS4B proteome and enriched in the MAMs, to perturb its functions in calcium homeostasis and apoptosis (Poston et al., 2013, Naghdi and Hajnoczky, 2016).

In conclusion, we provide compelling evidence for a mechanism of innate immunity interference by DENV that relies on virus-modulated morphodynamics of the mitochondria and their physical interactions with membranous viral replication factories. This subversion of innate immunity by DENV may have important implications for a better understanding of disease pathogenesis.

Experimental Procedures

Further details of used experimental procedures are given in Supplemental Information.

Cell Lines and Virus Strains

Naive cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 1% nonessential amino acids (complete DMEM). Production of virus stocks and determination of virus titers by plaque assays are specified in the Supplemental Information.

Live Cell Imaging

Huh7 reporter cells (2 × 105) were seeded into a 35-mm diameter glass bottom culture dish (MatTek). Cells were infected with a MOI of 10 for 1 hr at 37°C with occasional rocking. After removal of the inoculum, cells were washed thrice with PBS, and 2 ml phenol red-free DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal calf serum was added. Image series of DENV-infected cells were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope using a 40× Plan-Apo N.A. 0.95 objective (Nikon). Forty to 60 observation fields were defined, and image acquisition was performed at intervals of 1 hr for 72 hr by using the automated Nikon perfect focus system and CFP as well as YFP filters. Images were analyzed with the Nikon NIS Element Advanced Research program and processed by using the image processing package Fiji.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Cells grown on glass coverslips were washed twice with pre-warmed PBS and fixed by 30 min incubation with 2.5% glutaraldehyde/2% sucrose in 50 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (CaCo) supplemented with 50 mM KCl, 2.6 mM MgCl2 and 2.6 mM CaCl2. After three washes with 50 mM CaCo, cells were incubated with 2% osmium tetroxide/50 mM CaCo for 40 min on ice, washed with water three times, and treated with 0.5% uranyl acetate for 30 min. After 30 min rinsing with water, cells were progressively dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol (40% to 100%) and finally infiltrated in a polymerizing Epon/araldite resin (Araldite 502/Embed 812 kit; Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 72 hr at 60°C. Embedded cells were sectioned into 65-nm slices by using an Ultracut UCT microtome (Leica) and a diamond knife (Diatome). After counterstaining with 3% uranyl acetate in 70% methanol for 5 min and 2% lead citrate in water for 2 min, cells were examined with an EM-10 transmission electron microscope (Zeiss) with a built-in MegaView camera (Olympus). The length of mitochondria was measured using the ImageJ software package.

Correlative Light-Electron Microscopy

Huh7 cells stably expressing YFP-Sec61β and mito-mTurquoise2 were grown in 6-cm diameter dishes (Mattek) containing gridded coverslips and infected with DVs at a MOI of 1. Three days post infection, cells were washed twice and fixed by 20 min incubation with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. After several times washing with PBS, cells were examined with an Ultraview ERS spinning disc (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) on a Nikon TE2000-E inverted confocal microscope. Cells of interest were selected, and 0.13-μm optical sections in the cyan and YFP channels were acquired. The corresponding coordinates were also recorded using transmitted light with a differential interference contrast configuration. Cells were prepared and embedded for TEM analysis as previously described, and blocks were trimmed around the cell of interest according to the recorded coordinates. Ultrathin sections were prepared and examined with an EM-10 transmission electron microscope (Zeiss) containing a built-in MegaView camera (Olympus). Using ultrastructural and fluorescent patterns of mitochondria morphology and distribution, EM images and corresponding confocal microscopy Z-stacks were superimposed with the Photoshop CS5.1 software package (Adobe) and used for correlation analysis.

Author Contributions

L.C.C. and R.B. designed the study. L.C.C. conducted most of the experiments. M.C. and I.R.B. have contributed equally to this work. M.C. prepared and imaged samples by TEM and CLEM. I.R.B. prepared the samples for FIB-SEM, which was conducted together with N.S. I.R.B. analyzed the FIB-SEM datasets and performed the 3D rendering. C.J.N. conducted subcellular fractionations. Y.S provided equipment and expertise for the FIB-SEM. S.B. and P.S. contributed to the analysis of the IFN response by real-time PCR. W.F. generated the NS4B-HA-expressing DVs and prepared the samples for quantitative mass spectrometry analysis, which was evaluated by B.F. A.R. performed live-cell imaging. L.C.C. and R.B. wrote the manuscript. R.B. supervised the study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Vibor Laketa and the Infectious Diseases Imaging Platform (IDIP) at the Department of Infectious Diseases, University Hospital Heidelberg, for providing excellent microscopy support. We acknowledge Progen Biotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg for providing DENV serotypes 1, 3, and 4; Andrew Davidson for the NGC strain; Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit for the WNV NY99 strain; and the European Virus Archive for ZIKV strains. We thank Uta Haselmann, Marie Bartenschlager, Ulrike Herian, and Jacomine Krijnse-Locker for technical help; Dr. Didier Trono for lentivirus packaging constructs; Dr. Nathan R. Brady for DRP1 cDNA; Dr. Gualtiero Alvisi for constructing the YFP-Sec61β-encoding plasmid; and Drs. Eliana G. Acosta, Anil Kumar, David Paul, and Philippe Metz for virus stock production. We thank Dr. Birgit Voigt, proteomics platform of the Institute of Microbiology, University of Greifswald, for mass spectrometry-based analysis of the DENV NS4B interactome. We are grateful to the Electron Microscopy Core Facility of the University of Heidelberg and at the EMBL for expert support and providing access to their equipment. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 638, TP A5, and SFB 1129, TP11) to R.B. and SFB 1129 (TP13) to A.R.

Published: August 18, 2016

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven figures, one table, and six movies and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.008.

Contributor Information

Laurent Chatel-Chaix, Email: laurent.chatel-chaix@iaf.inrs.ca.

Ralf Bartenschlager, Email: ralf.bartenschlager@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

Supplemental Information

Mitochondria (red), NS3 (blue) and NS4B (green). Optical sections were acquired with a spinning disc confocal microscope and after deconvolution, Zstacks were used for 3D reconstruction. The movie was generated with the Imaris 8 software package and shows the proximity of NS3/NS4B-containing punctae to DENV-induced elongated mitochondria.

Uninfected (left panel) or infected with DENV2 DVs (MOI = 10; right panel). Every hour, the signal in the Cyan channel was acquired. Time and scale bar are indicated in the movie. The movie shows time-dependent DENV-induced elongation of mitochondria until cell death because of cytopathic effects caused by DENV.

MOI = 10. The signal in the cyan channel was acquired every hour. Time post-infection and scale bar are indicated in the movie. The movie shows time-dependent DENV-induced elongation of mitochondria until cell death because of cytopathic effects caused by DENV.

DENV2 NGC-infected Huh7 cell (24 hr post infection; MOI = 5). Images of transversal sections of approximately 10 nm were acquired and used for 3D reconstruction. Reconstructed mitochondria are shown in red and DENV convoluted membranes in green. Note the elongated mitochondrial network with CMs in close proximity to mitochondria. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Every hour, the signals in the Cyan and YFP channels were acquired. The movie shows the dynamics of the mitochondrial network. No accumulation of YFP-Sec61β punctae could be observed. Time and scale bar are indicated in the movie. Left: Combined imaging of both YFP-Sec61β and mito-Turquoise2. Right: Imaging of YFPSec61β only.

MOI = 10. Every hour, the signals in the Cyan and YFP channels were acquired. The movies show the dynamics of the mitochondrial network. The bottom movie highlights the continuous contacts between elongated mitochondria and CMs during infection. It also pinpoints the dynamic features of CMs undergoing merging and division events (still images shown in Figure S6A). Time post-infection and scale bar are indicated in the movies. Left: Combined imaging of both YFP-Sec61β and mito-Turquoise2. Right: Imaging of YFP-Sec61β only. Still images of the top movie are shown in Figure S6B.

References

- Acosta E.G., Kumar A., Bartenschlager R. Revisiting dengue virus-host cell interaction: new insights into molecular and cellular virology. Adv. Virus Res. 2014;88:1–109. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800098-4.00001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre S., Maestre A.M., Pagni S., Patel J.R., Savage T., Gutman D., Maringer K., Bernal-Rubio D., Shabman R.S., Simon V. DENV inhibits type I IFN production in infected cells by cleaving human STING. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002934. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S., Gething P.W., Brady O.J., Messina J.P., Farlow A.W., Moyes C.L., Drake J.M., Brownstein J.S., Hoen A.G., Sankoh O. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanier C., Garcin D., Vazquez A., Arnoult D. Mitochondrial dynamics regulate the RIG-I-like receptor antiviral pathway. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:133–138. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D.C. Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:265–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y.K., Gack M.U. A phosphomimetic-based mechanism of dengue virus to antagonize innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:523–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatel-Chaix L., Bartenschlager R. Dengue virus- and hepatitis C virus-induced replication and assembly compartments: the enemy inside--caught in the web. J. Virol. 2014;88:5907–5911. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03404-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatel-Chaix L., Fischl W., Scaturro P., Cortese M., Kallis S., Bartenschlager M., Fischer B., Bartenschlager R. A Combined Genetic-Proteomic Approach Identifies Residues within Dengue Virus NS4B Critical for Interaction with NS3 and Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2015;89:7170–7186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00867-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Dorn G.W., 2nd PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. 2013;340:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Detmer S.A., Ewald A.J., Griffin E.E., Fraser S.E., Chan D.C. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J. Cell Biol. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple N.A., Cimica V., Mackow E.R. Dengue Virus NS Proteins Inhibit RIG-I/MAVS Signaling by Blocking TBK1/IRF3 Phosphorylation: Dengue Virus Serotype 1 NS4A Is a Unique Interferon-Regulating Virulence Determinant. MBio. 2015;6 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00553-15. e00553–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J.R., Lackner L.L., West M., DiBenedetto J.R., Nunnari J., Voeltz G.K. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334:358–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1207385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser L., Sonnay S., Stafa K., Moore D.J. Parkin promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of the mitochondrial fusion factor mitofusin 1. J. Neurochem. 2011;118:636–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner S.M., Liu H.M., Park H.S., Briley J., Gale M., Jr. Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:14590–14595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110133108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakumani P.K., Ponia S.S., Rajgokul K.S., Sood V., Chinnappan M., Banerjea A.C., Medigeshi G.R., Malhotra P., Mukherjee S.K., Bhatnagar R.K. Role of RNA interference (RNAi) in dengue virus replication and identification of NS4B as an RNAi suppressor. J. Virol. 2013;87:8870–8883. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02774-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.J., Syed G.H., Khan M., Chiu W.W., Sohail M.A., Gish R.G., Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus triggers mitochondrial fission and attenuates apoptosis to promote viral persistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:6413–6418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321114111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoops K., Kikkert M., Worm S.H., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Koster A.J., Mommaas A.M., Snijder E.J. SARS-coronavirus replication is supported by a reticulovesicular network of modified endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korobova F., Ramabhadran V., Higgs H.N. An actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the ER-associated formin INF2. Science. 2013;339:464–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1228360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboucher G.P., Tsai Y.C., Yang M., Shaw K.C., Zhou M., Veenstra T.D., Glickman M.H., Weissman A.M. Stress-induced phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of mitofusin 2 facilitates mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2012;47:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Yoon Y. Mitochondrial fission: regulation and ER connection. Mol. Cells. 2014;37:89–94. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor U., Bartholomew S., Golani G., Christenson E., Kozlov M., Higgs H., Spudich J., Lippincott-Schwartz J. A mitochondria-anchored isoform of the actin-nucleating spire protein regulates mitochondrial division. eLife. 2015;4:e08828. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean J.E., Wudzinska A., Datan E., Quaglino D., Zakeri Z. Flavivirus NS4A-induced autophagy protects cells against death and enhances virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22147–22159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S., Kastner S., Krijnse-Locker J., Bühler S., Bartenschlager R. The non-structural protein 4A of dengue virus is an integral membrane protein inducing membrane alterations in a 2K-regulated manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8873–8882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Jordan J.L., Sánchez-Burgos G.G., Laurent-Rolle M., García-Sastre A. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14333–14338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335168100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Jordán J.L., Laurent-Rolle M., Ashour J., Martínez-Sobrido L., Ashok M., Lipkin W.I., García-Sastre A. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. J. Virol. 2005;79:8004–8013. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8004-8013.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghdi S., Hajnoczky G. VDAC2-specific cellular functions and the underlying structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.04.020. Published online April 23, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olichon A., Baricault L., Gas N., Guillou E., Valette A., Belenguer P., Lenaers G. Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7743–7746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoguchi K., Onomoto K., Takamatsu S., Jogi M., Takemura A., Morimoto S., Julkunen I., Namiki H., Yoneyama M., Fujita T. Virus-infection or 5’ppp-RNA activates antiviral signal through redistribution of IPS-1 mediated by MFN1. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001012. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otera H., Wang C., Cleland M.M., Setoguchi K., Yokota S., Youle R.J., Mihara K. Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:1141–1158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul D., Bartenschlager R. Architecture and biogenesis of plus-strand RNA virus replication factories. World J. Virol. 2013;2:32–48. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v2.i2.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poston C.N., Krishnan S.C., Bazemore-Walker C.R. In-depth proteomic analysis of mammalian mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM) J. Proteomics. 2013;79:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyakurel A., Savoia C., Hess D., Scorrano L. Extracellular regulated kinase phosphorylates mitofusin 1 to control mitochondrial morphology and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2015;58:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C.S., Qi H.Y., Boularan C., Huang N.N., Abu-Asab M., Shelhamer J.H., Kehrl J.H. SARS-coronavirus open reading frame-9b suppresses innate immunity by targeting mitochondria and the MAVS/TRAF3/TRAF6 signalosome. J. Immunol. 2014;193:3080–3089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova E., Shurland D.L., Ryazantsev S.N., van der Bliek A.M. A human dynamin-related protein controls the distribution of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:351–358. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova E., Griparic L., Shurland D.L., van der Bliek A.M. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2245–2256. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack S., Cribbs J.T. Allosteric modulation of Drp1 mechanoenzyme assembly and mitochondrial fission by the variable domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:10990–11001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Xing Y., Chen X., Zheng Y., Yang Y., Nichols D.B., Clementz M.A., Banach B.S., Li K., Baker S.C., Chen Z. Coronavirus papain-like proteases negatively regulate antiviral innate immune response through disruption of STING-mediated signaling. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet A.R., Verfaillie T., Agostinis P. New functions of mitochondria associated membranes in cellular signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843:2253–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance J.E. MAM (mitochondria-associated membranes) in mammalian cells: lipids and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1841:595–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch S., Miller S., Romero-Brey I., Merz A., Bleck C.K., Walther P., Fuller S.D., Antony C., Krijnse-Locker J., Bartenschlager R. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westaway E.G., Mackenzie J.M., Kenney M.T., Jones M.K., Khromykh A.A. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J. Virol. 1997;71:6650–6661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6650-6661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2009. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis,Treatment, Prevention and Control. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M., Gonzalez P., Li C., Meng G., Jiang A., Wang H., Gao Q., Debatin K.M., Beltinger C., Wei J. Mitophagy enhances oncolytic measles virus replication by mitigating DDX58/RIG-I-like receptor signaling. J. Virol. 2014;88:5152–5164. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03851-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Zou J., Wang Q.Y., Shi P.Y. Targeting dengue virus NS4B protein for drug discovery. Antiviral Res. 2015;118:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa K., Oshiumi H., Takeda M., Ishihara N., Yanagi Y., Seya T., Kawabata S., Koshiba T. Mitofusin 2 inhibits mitochondrial antiviral signaling. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra47. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi T., Ichinohe T., Sasaki O., Otera H., Kawabata S., Mihara K., Koshiba T. Influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 translocates into mitochondria via Tom40 channels and impairs innate immunity. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4713. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C.Y., Chang T.H., Liang J.J., Chiang R.L., Lee Y.L., Liao C.L., Lin Y.L. Dengue virus targets the adaptor protein MITA to subvert host innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002780. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C.Y., Liang J.J., Li J.K., Lee Y.L., Chang B.L., Su C.I., Huang W.J., Lai M.M., Lin Y.L. Dengue Virus Impairs Mitochondrial Fusion by Cleaving Mitofusins. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005350. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziviani E., Tao R.N., Whitworth A.J. Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913485107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mitochondria (red), NS3 (blue) and NS4B (green). Optical sections were acquired with a spinning disc confocal microscope and after deconvolution, Zstacks were used for 3D reconstruction. The movie was generated with the Imaris 8 software package and shows the proximity of NS3/NS4B-containing punctae to DENV-induced elongated mitochondria.

Uninfected (left panel) or infected with DENV2 DVs (MOI = 10; right panel). Every hour, the signal in the Cyan channel was acquired. Time and scale bar are indicated in the movie. The movie shows time-dependent DENV-induced elongation of mitochondria until cell death because of cytopathic effects caused by DENV.

MOI = 10. The signal in the cyan channel was acquired every hour. Time post-infection and scale bar are indicated in the movie. The movie shows time-dependent DENV-induced elongation of mitochondria until cell death because of cytopathic effects caused by DENV.

DENV2 NGC-infected Huh7 cell (24 hr post infection; MOI = 5). Images of transversal sections of approximately 10 nm were acquired and used for 3D reconstruction. Reconstructed mitochondria are shown in red and DENV convoluted membranes in green. Note the elongated mitochondrial network with CMs in close proximity to mitochondria. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Every hour, the signals in the Cyan and YFP channels were acquired. The movie shows the dynamics of the mitochondrial network. No accumulation of YFP-Sec61β punctae could be observed. Time and scale bar are indicated in the movie. Left: Combined imaging of both YFP-Sec61β and mito-Turquoise2. Right: Imaging of YFPSec61β only.

MOI = 10. Every hour, the signals in the Cyan and YFP channels were acquired. The movies show the dynamics of the mitochondrial network. The bottom movie highlights the continuous contacts between elongated mitochondria and CMs during infection. It also pinpoints the dynamic features of CMs undergoing merging and division events (still images shown in Figure S6A). Time post-infection and scale bar are indicated in the movies. Left: Combined imaging of both YFP-Sec61β and mito-Turquoise2. Right: Imaging of YFP-Sec61β only. Still images of the top movie are shown in Figure S6B.