Abstract

New imaging methods are needed to assess the activity of caries lesions on tooth surfaces. Recent studies have shown that thermal imaging of lesions on root surfaces during dehydration with air can be used to determine if the lesions are active or arrested. In this study changes in the thermal emission of root caries lesions on extracted teeth during dehydration with air was monitored using an imaging system with a miniature thermal camera and a 3D printed handpiece with an integrated air nozzle suitable for clinical use. This study evaluated the performance of the thermal camera for imaging root caries on extracted teeth prior to it’s use for in vivo studies. There was a significant difference in the thermal response of sound and root lesion areas of human teeth under dehydration at constant airflow.

Keywords: thermal imaging, caries detection, reflectance imaging, lesion activity

1. INTRODUCTION

Clinical diagnosis of root caries is highly subjective and is based on visual and tactile parameters. In contrast to coronal caries, root caries lacks a valid diagnostic standard, such as radiography [1]. Moreover, early root caries lesions are much more difficult to detect than the early incipient white spot lesions seen with coronal caries. There are often no clinical symptoms with root caries, although pain may be present in advanced lesions. Traditional methods of visual-tactile diagnosis for root caries can result in a correct diagnosis, but not until the lesion is at an advanced stage [1]. In addition, investigators have not developed a reliable relationship between lesion appearance and activity [2–4]. Even though most experts agree that active root lesions are soft, tactile hardness assessments remain subjective and lack reliability [2]. Multifactorial root caries scoring systems have been developed with mixed success [5, 6]. More recently, the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) coordinating committee and Ekstrand et al. proposed clinical scoring systems for assessing root caries lesion activity [5, 7]. Criteria include: color (light /dark brown, black); Texture (smooth, rough); Appearance (shiny or glossy, matte or non-glossy); Tactile (soft, leathery, hard); Cavitation (loss of anatomical contour); and proximity to the gingival margin [8]. However, such clinical methods for root caries lesion activity assessment lack histological validation and are composed of only visual and tactile exams, which are prone to subjective bias and interference from staining [9]. Histological analyses for lesion assessment such as transverse microradiography (TMR) and polarized light microscopy (PLM) require destruction of the tooth and are not suitable for use in vivo. Incorrect diagnosis can result in under treatment or over treatment. If a decision to restore is made prematurely when remineralization was feasible, the patient is committed to a restoration, or replacement restorations, that can become progressively larger. If the lesion is active and intervention is delayed, often the patient will require a root canal or extraction.

Although the penetration depth of near-IR light is limited in dentin compared to enamel, high quality images of early root caries and demineralization in dentin are feasible [14]. CP-OCT has been used successfully to measure demineralization in simulated caries models in dentin and on root surfaces (cementum) [12, 15, 16]. CP-OCT has also been used to measure remineralization on dentin surfaces and to detect the formation of a highly mineralized layer on the lesion surface after exposure to a remineralization solution [16]. OCT has also been used to help discriminate between noncarious cervical lesions and root caries in vivo [17]. Kaneko et al. and Zakian et al. [18, 19] demonstrated that lesions on coronal surfaces could be differentiated from sound enamel in thermal images. We recently demonstrated that thermal imaging via dehydration can be used to assess lesion activity on both enamel [20] and dentin surfaces. In previous studies, thermal imaging during lesion dehydration was more successful than near-IR imaging for assessing lesion activity on root and dentin surfaces [21]. In this study we built a handheld thermal imaging probe with a miniature thermal camera and a 3D printed handpiece with an integrated air nozzle suitable for clinical use. We evaluated the performance of the handheld thermal imaging probe for imaging root caries on extracted teeth prior to use for in vivo studies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample Preparation

Teeth (n=16) containing root lesions extracted from patients in the San Francisco Bay Area were collected, cleaned, sterilized with gamma radiation, and stored in a 0.1% thymol solution. These teeth were then mounted on 1.2 x 3 cm rectangular blocks of black orthodontic composite resin with the outward tooth lesion surface facing upwards.

2.2. Handheld Thermal Imaging System

Thermal images were captured using a FLIR Boson 640 (Wilsonville, Oregon) thermal camera that uses an uncooled vanadium oxide microbolometer with a 12 μm pixel pitch, a 640 x 512 array and a thermal sensitivity of 50 mK. The spectral range is 7.5 - 13.5 μm. The size of the camera itself is only 21 x 11 x 11 mm equivalent to a 4.9 cm3 volume. The camera was equipped with the integrated 24 mm focal length lens and an additional 100 mm focal length planoconvex ZnSe lens was attached to a handpiece 3D-printed using a Formlabs 2 printer (Somerville, MA) as shown in Fig. 1. The handpiece was printed using the standard black resin and a right angle mirror was attached at the distal end of the handpiece. An air nozzle was attached to the appliance to provide air to dehydrate lesion and sound areas at a set airflow. Image acquisition was carried out using a custom program using Labview™ from National Instruments (Austin, TX).

Fig. 1.

3D printed prototype appliance for use with the CP-OCT handpiece. The window is centered over the lesion and forced air is delivered through the cylindrical shaped channel to the window.

For this study, 16 extracted teeth containing root lesions stored in 0.1% thymol solution prior to imaging were used. Samples were removed from the solution and placed under the window of the handpiece in contact for thermal capture. The resolution of each captured frame was 293 x 277 pixels. Airflow over the samples was set at 5 psi. Frames were captured at 4 frames per second for a period of 60 seconds. Thermal images acquired at different time points over a period of 60 seconds of drying are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Thermal images over time (0, 7.5, 15, 30, and 60 seconds drying elapsed) show the behavior of the lesion compared to the corresponding sound surfaces.

2.3. Analysis of Thermal Emission Curves

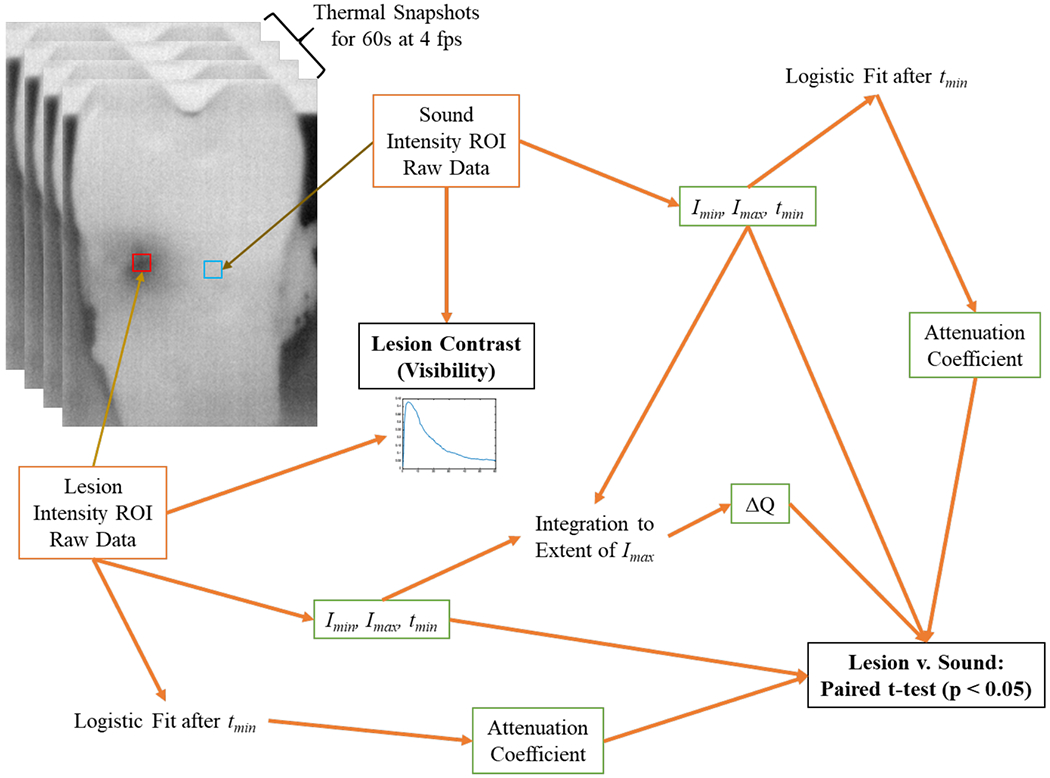

Figure 3 provides a flowchart of the steps taken in analyzing the thermal images. For each sample, a 5x5 pixel lesion area and corresponding 5x5 sound area were identified as regions of interest (ROI). These two areas were tracked over the total duration of time for intensity changes. For each 5x5 area, the intensity of all pixels within that area was averaged at each time point.

Fig. 3.

Outline of steps taken in the processing of the thermal images.

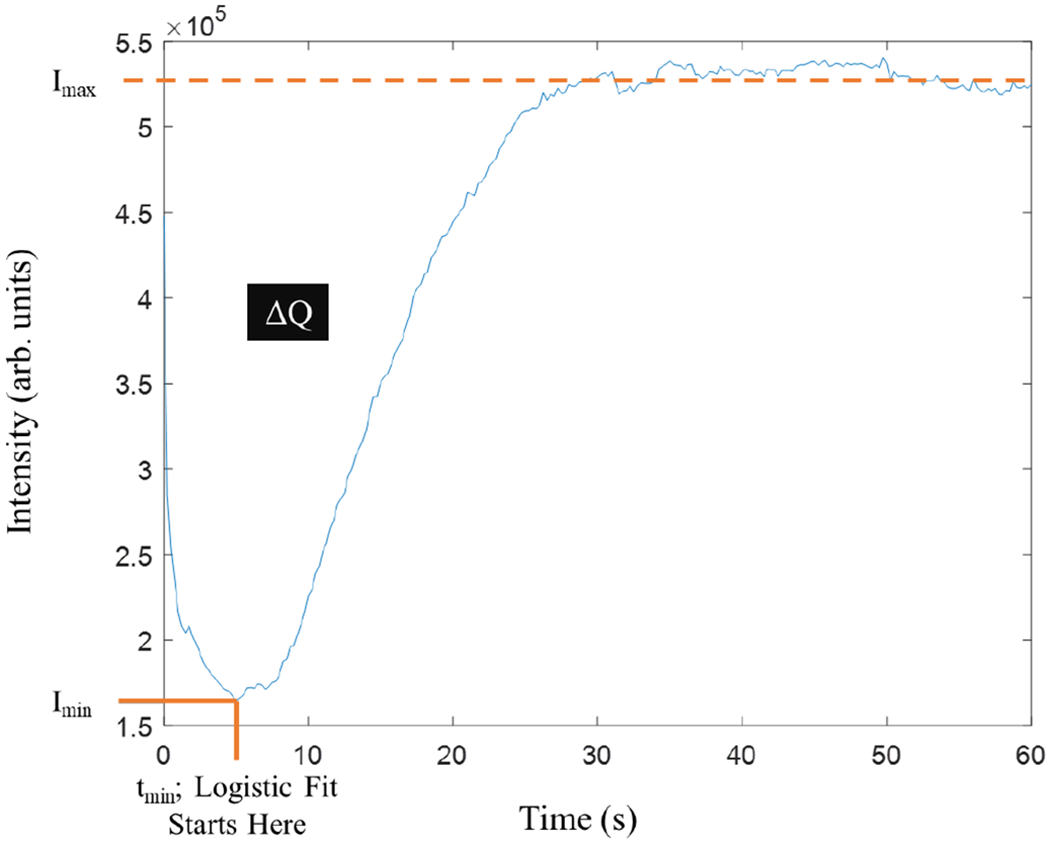

Thermal curves were inspected and found to have a sharp dip in intensity, followed by a gradual asymptotic growth to a final intensity level. This behavior corresponds to the evaporation of water, cooling the surface of the tooth, and then gradual warming back to ambient temperature. To simplify analysis, the curves were split in two at the minimum intensity. The minimum intensity is where the intensity changes from a negative to a positive slope and is representative of the coolest temperature the sample reaches over the experimental time. The corresponding time and intensity at that point are noted as tmin and Imin, respectively. The maximum intensity, Imax, is the intensity reached after complete thermal drying. These three values are shown on the sample curve in Fig. 4, which is a sample thermal curve of one lesion area of one sample. The intensity values over time after this cutoff were normalized, smoothed using a moving average over 5 time points, and fitted to a three-parameter logistic growth curve. The fit equation is: I = 1/(1+exp(a*(t-b)))+c, where “a” is the growth coefficient. It characterizes the growth in intensity over time.

Fig. 4.

A plot of intensity vs time for the thermal emission showing Imin, Imax, ΔQ and growth start times.

Another important value is integrated intensity. It is a representative measure of heat leaving the tooth at the region of interest. This value can be found by integrating the area of the curve above the intensity versus time graph, but below the maximum intensity reached. The area is represented in Fig. 4 as ΔQ.

Contrast was calculated over the 60 seconds of drying and is a measure of the visibility of the lesion against the sound surface. Contrast is calculated by taking the difference in intensities between the sound and lesion ROIs and dividing the result by the intensity of the sound ROI. In other words, (IS-IL)/IS for each timepoint.

Growth coefficient, minimum and maximum intensities, ΔQ, and growth start time values were compared between sound and lesion areas using paired t-tests. If p < 0.05, then the difference between data was considered significantly different. Tests were carried out using Graphpad Prism (San Diego, CA).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A comparison of the images for the 16 samples indicated that there were significant differences (P < 0.05) for the growth coefficients, minimum intensities, ΔQ and growth start times between sound and lesion areas, while there was no significant difference for the maximum intensity. Further in vitro studies will be carried out comparing active and arrested root caries lesions. Moreover, we have just completed a clinical study on 30 test subjects in which root caries lesions were imaged in vivo using this imaging handpiece along with cross polarization optical coherence tomography (CP-OCT). The thermal imaging appeared to work well in vivo, and changes in the thermal emission of the lesions were clearly visible. For the clinical study the handpiece was printed with Formlabs high-temperature Dental SG resin which is biocompatible and autoclavable. The results of the clinical study will be submitted for publication in the near future.

Lesion activity is an important characteristic to consider, because it determines whether treatment should be given or withheld. Histological analyses for lesion assessment such as transverse microradiography (TMR) and polarized light microscopy (PLM) require destruction of the tooth and are not suitable for use in-vivo. Incorrect diagnosis can result in undertreatment or overtreatment. If a decision to restore is made prematurely when remineralization was feasible, the patient is committed to a restoration and often replacement restorations can become progressively larger. If the lesion is active and intervention is delayed, often the patient will require a more invasive and expensive restorative procedure.

There was a significant difference in the thermal response of sound and root lesion areas of human teeth under dehydration at constant airflow. Future studies will attempt to discern between active and arrested lesion areas and understand how active lesions respond to treatment in-vivo under clinically relevant timescales.

4. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of NIDCR/NIH grants R01-DE027335 and F30-DE027264 and TRDRP grant 27IP-0015. The authors would like to thank Yihua Zhu and Jacob Simon for their contribution to this work.

5. REFERENCES

- [1].Banting DW, Diagnosis of Root Caries NIH Consensus Statement, (2001).

- [2].Banting DW, “Diagnosis and prediction of root caries,” Adv Dent Res, 7(2), 80–6 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hellyer P, Beighton D, Heath M, and Lynch E, “Root caries in older people attending a general practice in East Sussex,” Brit Dent J 169, 201–206 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schaeken M, Keltjens H, and Van der Hoeven J, “Effects of fluoride and chlorhexidine on the microflora of dental root surfaces and progression of root-surface caries,” J Dent Res, 70, 150–153 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ekstrand K, Martignon S, and Holm-Pedersen P, “Development and evaluation of two root caries controlling programmes for home-based frail people older than 75 years,” Gerodontology, 25(2), 67–75 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fejerskov O, Luan WM, Nyvad B, Budtz-Jorgensen E, and Holm-Pedersen P, “Active and inactive root surface caries lesions in a selected group of 60- to 80-year-old Danes,” Caries Res, 25(5), 385–91 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ismail A, Banting D, Eggertsson H, Ekstrand K, Ferreira-Zandona A, Longbottom C, Pitts N, Reich E, Ricketts D, Selwitz R, Sohn W, Topping G, and Zero D, “Rationale and evidence for the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS II),” In Proceedings of the 7th Indiana Conference Indiana University, Vol. 4, 161–221 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pitts N, Detection, Assessment, Diagnosis and Monitoring of Caries, Monographs in Oral Science Vol. 21 Karger, Basel: (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lynch E, and Beighton D, “A comparison of primary root caries lesions classified according to colour,” Caries Res, 28(4), 233–9 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jones RS, Darling CL, Featherstone JD, and Fried D, “Remineralization of in vitro dental caries assessed with polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography,” J Biomed Optics, 11(1), 014016 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jones RS, and Fried D, “Remineralization of enamel caries can decrease optical reflectivity,” J Dent Res, 85(9), 804–8 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Manesh SK, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Nondestructive assessment of dentin demineralization using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography after exposure to fluoride and laser irradiation,” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, 90(2), 802–12 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kang H, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Nondestructive monitoring of the repair of enamel artificial lesions by an acidic remineralization model using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography,” Dent Mat, 28(5), 488–494 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Amaechi BT, Podoleanu AG, Komarov G, Higham SM, and Jackson DA, “Quantification of root caries using optical coherence tomography and microradiography: a correlational study,” Oral Health Prev Dent, 2(4), 377–82 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee C, Darling C, and Fried D, “Polarization Sensitive Optical Coherence Tomographic Imaging of Artificial Demineralization on Exposed Surfaces of Tooth Roots,” Dent Mat, 25(6), 721–728 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Manesh SK, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography for the nondestructive assessment of the remineralization of dentin,” J Biomed Optics, 14(4), 044002 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wada I, Shimada Y, Ikeda M, Sadr A, Nakashima S, Tagami J, and Sumi Y, “Clinical assessment of non carious cervical lesion using swept-source optical coherence tomography,” J Biophotonics, 8(10), 846–54 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kaneko K, Matsuyama K, and Nakashima S, “Quantification of Early Carious Enamel Lesions by using an Infrared Camera,” Early detection of Dental caries II. Indiana University, Vol. 2 483–99 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zakian CM, Taylor AM, Ellwood RP, and Pretty IA, “Occlusal caries detection by using thermal imaging,” J Dent, 38(10), 788–795 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee RC, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Assessment of remineralization via measurement of dehydration rates with thermal and near-IR reflectance imaging,” J Dent, 43, 1032–1042 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lee RC, Darling CL, and Fried D, “Activity assessment of root caries lesions with thermal and near-infrared imaging methods,” J Biophotonics, 10(3), 433–445 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yang VB, Curtis DA, Fried D, and “Use of Optical Clearing Agents for Imaging Root Surfaces with Optical Coherence Tomography ” IEEE J Sel Topics Quant Elect, 25(1), 1–7 (2018). [Google Scholar]