Abstract

The present work was to investigate graphene oxide (GO) decorated with glycyrrhizin (GL) which were conjugated via strong hydrogen-bonding interaction as a new hepatocyte-targeted delivery vehicle. The hydrogen-bonding interaction, simplified as a non-covalent type of functionalization, enables high drug loading and subsequent controlled release of the drug. An effective loading of GL on GO as high as 5.19 mg/mg was obtained at initial GL concentration of 0.6 mg/mL. The release of GL on GO showed strong pH dependence and the extent of release at pH 5.5 and 7.4 is 58.4% and 17.6% over 30 h in vitro respectively. The results show that the GO-GL complex seems to be a very promising vehicle for loading of drugs under neutral conditions and releasing under acidic environment. Furthermore, GO-GL can be obtained under mild conditions without addition of any organic solvents and surfactants, which is very suitable for pharmaceutical applications as a promising hepatocyte-targeted delivery carrier.

Keywords: Glycyrrhizin, Graphene oxide, Hepatocyte-targeted, Drug delivery

1. Introduction

Tumor-specific delivery of anticancer drugs maximizes the efficacy of drugs and minimizes their off-target effects. The aim of targeted delivery is to selectively accumulate drug in the target site. The liver is an important target tissue for drug therapy, because many fatal diseases such as chronic hepatitis, enzyme deficiency and hepatoma occur in hepatocytes. Hence, it is important to target drugs to the hepatocytes in order to enhance the uptake efficiency by hepatocytes.

Glycyrrhizin (GL) has attracted much attention due to its anti-inflammatory, antiallergenic, antihepatotoxic, antiulcer and antiviral properties [1]. Furthermore, GL is one of the leading natural compounds for clinical trials in recent studies on chronic viral hepatitis (such as Hepatitis A virus [HAV] [2], Hepatitis B virus [HBV] [3], and Hepatitis C virus [HCV] [4] and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infections) [5]. The antiviral activity of GL against SARS associated corona virus has been demonstrated in vitro [6]. In addition, GL finds application in inhibiting unwanted effects of contraceptive formulations, such as alterations in blood coagulation and thrombosis [7].

In recent decades, GL has emerged as a prominent targeting moiety capable of specific interaction with cells. It has been proved that there are specific binding sites of GL on the cellular membrane of in vitro rat hepatocytes [8]. More recently, Ismair et al. [9] have found that carrier-mediated transport system absorbed GL can participate into rat or human hepatocytes. Based on these researches, some new drug carriers, surface-modified with GL (such as liposomes, albumin nanoparticles and chitosan) were prepared and proved to be more efficient on hepatocyte-targeted delivery compared with the conventional ones [10]. These results imply that GL may be used as a novel ligand for hepatocyte-specific delivery.

The site-specific delivery of drugs to the tumors using GL can be enhanced by high capacity carriers in which multiple drug molecules can be simultaneously incorporated and targeted to disease sites. A recent example of high capacity carrier is graphene which has been the major focus of recent research due to its outstanding low toxicity, large specific surface area, mechanical, electrical, thermal, and optical properties since its first discovery in 2004 [11], leading to the potential applications in many different areas including drug delivery [12]. Compared with graphene, graphene oxide (GO) is a heavily oxygenated material which has hydroxyl and epoxide functional groups on its basal planes, carbonyl and carboxyl groups at the sheet edges. Due to its hydrophilicity, GO can be well dispersed in aqueous media. In addition, GO provides large specific surface area for the immobilization of various biomolecules, which makes it a promising material as a drug carrier substance.

Herein, based on the medicinal value of GL in many fatal diseases, targeting capability to hepatocytes and the merit of GO, a novel non-covalent nanohybrid hepatocyte-targeted delivery consisting of GO and GL was prepared and the in vitro binding and release behaviors were investigated. The amount of GL loaded onto GO was found to be significantly high and dependent on the pH value. Furthermore, the interaction between GL and GO was also investigated by spectroscopy.

2. Experimental

2.1. Apparatus and chemicals

GL (HPLC degree ≥ 98%, Hefei Bomei Biotechnology Co., Ltd), graphite (Qingdao Fujin graphite Co., Ltd). All other chemicals used were of analytical-reagent grade.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (S-4800, Hitachi, Japan), Ultraviolet visible near IR spectrophotometer (UV) (755B, Shanghai), Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR) (Nicolet-550, Nicolet), Cyclic voltammetry (CV) (CHI-660A Shanghai Chen Hua Instrument Co., Ltd).

2.2. Preparation of GO

GO was obtained using the method reported by Hummers [13].

Generally, thermally treated graphite powder (5 g) was added to 98% H2SO4 (115 mL) in an ice bath. KMnO4 (20 g) was added slowly with stirring. The mixture was then maintained at 35 °C for 30 min, distilled water (100 mL) was gradually added, which resulted in an increase of temperature to 98 °C. After 20 min, there was further added to the mixture distilled water (700 mL) and 30% H2O2 solution until no bubbles observed. The obtained GO was washed with distilled water until pH approaches 7, then dried at 60 °C in vacuum.

2.3. Fabrication of GL modified GO (GO-GL)

GO with a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL (40% ethanol solution) and GL with a certain concentration (40% ethanol solution) at a certain pH value was first sonicated for 0.5 h, then mixed and stirred 24 h at 37 °C. After being filtered and washed with distilled water, the sediment was dried at 60 °C in vacuum. The obtained sample was named as GO-GL.

2.4. Measurement of GL with UV spectroscopy

GL concentration was measured using a standard GL concentration curve generated using the UV-vis spectrophotometer at the wavelength of 245 nm.

The loading of GL on GO is calculated by Eq. (1)

| (1) |

where Φ is the amount of GL loaded on GO, M GL is the initial amount of GL, M GL’ is the amount of GL in the upper layer, and M GO is the total amount of GO.

2.5. Release of GL

The GO-GL (10 mg) was dispersed in 6 mL of distilled water and the dispersion was divided into three equal aliquots. The GO-GL samples used for the release experiments were placed into a dialysis chambers and dialyzed in 60 mL of aqueous solution at pH values of 5.5, 7.4 and 9.0. It was assumed that the release started as soon as the dialysis chambers were placed into the reservoir with constantly stirred. The concentration of GL released from GO-GL was quantified using UV spectroscopy.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of GO-GL

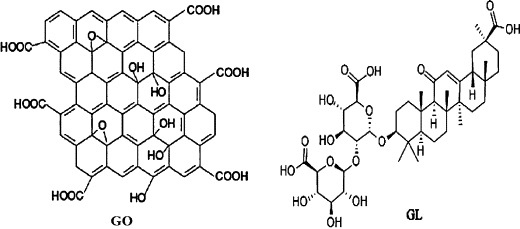

There are many hydroxyl and carboxyl groups in GO and GL as shown in Scheme 1 which could form a strong hydrogen-bonding interaction between the two components. Therefore, GL can be non-covalently loaded on GO simply by mixing them with the aid of slight sonication.

Scheme 1.

Structure of GO and GL.

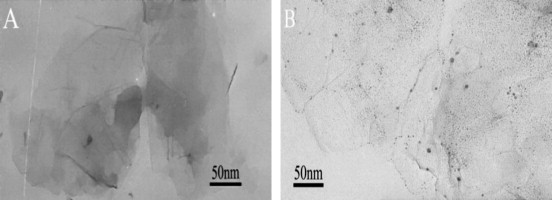

The morphology of GO before and after loading with GL was characterized by TEM, as shown in Fig. 1 . GO (Fig. 1A) shows a smooth surface with a size of several hundreds of nanometers, while many grains are observed on the surface of GO-GL nanohybrid, as shown in Fig. 1B. Obviously, a large amount of GL is well dispersed on GO.

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy of (A) GO and (B) GO-GL.

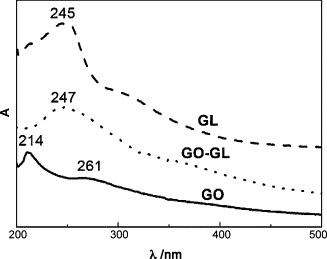

More convincing evidence came from UV-vis spectroscopy (Fig. 2 ). GO shows absorption bands at 261 and 214 nm, and free GL solution absorbs strongly at 245 nm. The stacking of GL onto GO was evident from the spectrum of the GO-GL nanohybrid solution, which shows the characteristic absorption peaks of GL and GO simultaneously. Moreover, after forming the nanohybrid, the absorption peaks of GL show red-shifts. For example, the peaks of GL at 245 nm shifted to 247 nm after hybridized with GO, which is generally believed as due to the ground-state electron donor-acceptor interaction between the two components [12b].

Fig. 2.

UV visible spectra of GL, GO and GO-GL in aqueous solution.

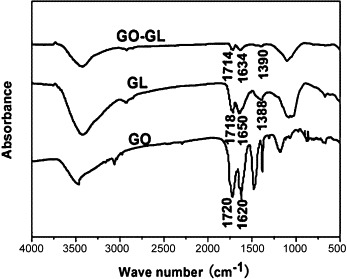

The FTIR spectra of GO, GL and GO-GL nanohybrid are shown in Fig. 3 . The peaks at 1388 and 1718 cm−1 are the fingerprint characteristic peaks of GL and the peaks are weaker for GO-GL. The peak at 1720 cm−1 corresponding to ν (C = O) in the spectrum of GO and the C = O peak (1718 cm−1) for GL shifts to a lower position at 1714 cm−1 after forming GO-GL nanohybrid. The peak at 1650 cm−1 corresponding to ν (C = C) in the spectrum of GL and the peak (1620 cm−1) for GO shift to the wavenumber of 1634 cm−1 after forming GO-GL nanohybrid. These also indicate that GL was loaded onto GO, and the shift of characteristic peaks may be due to the hydrogen bonding.

Fig. 3.

FTIR spectra of GL, GO and GO-GL.

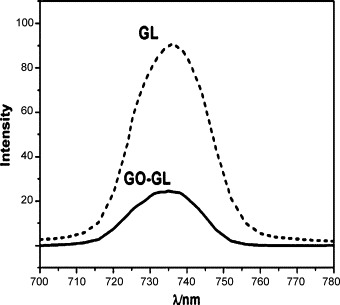

For the interaction between the GO and GL, the hydrogen-bonding interaction may be the most important one because the loading of GL on GO is lower in the case of decreasing of the hydrogen-bonding interactions under acidic conditions. Following the interaction between GO and GL in the excited-state using fluorescence spectroscopy is illustrated in Fig. 4 . Free GL exhibits a fluorescence emission maximum at 736 nm with an excited source at 250 nm. However, upon excitation at the same wavelength, GO-GL exhibits significant quenching of its emission band. These results imply the presence of a photo-induced electron-transfer process or efficient energy transferring along the GO-GL interface [14], and show that there is strong hydrogen-bonding interaction between GO and GL [15].

Fig. 4.

Fluorescence spectra of GO-GL and GL in water at the 250 nm excitation wavelength. The concentrations of both GO-GL and GL were all controlled to be the same according to the loading of GL on GO.

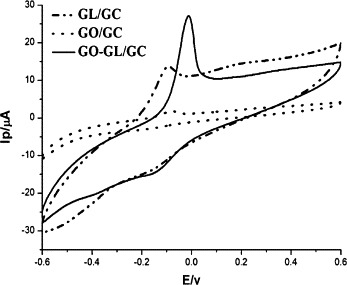

The compound behaviors of GO-GL were investigated by cyclic voltammetry. The concentrations of free GL and free GO were the same as that in the solution of GO-GL. Eight microlitres of the solution was cast on the surface of a glassy carbon electrode, Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode and platinum electrode as a counter electrode, the electrochemical measurements were carried out in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4). Fig. 5 compares the typical cyclic voltammetric curves using the GO-GL modified GC electrode (GO-GL/GC) and the GO- and GL-modified GC electrodes (GO/GC, GL/GC), respectively. The oxidation peak potential of GL at −0.096 V was observed. Compared to the oxidation peak current of GL at GL/GC, the oxidation peak current of GL at GO-GL/GC shows significant enhancement which may be attributed to more GL loading on GO. In addition, the peak potential of GL at GO-GL/GC shifts, which may be attributed to the hydrogen-bonding interactions between GO and GL.

Fig. 5.

Cyclic voltammetric curves of GL/GC, GO/GC, and GO-GL/GC at a 50 mV/s scan rate in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH7.4). Both GO and GL concentrations were controlled to be the same according to the loading of GL on GO.

3.2. GL loading test

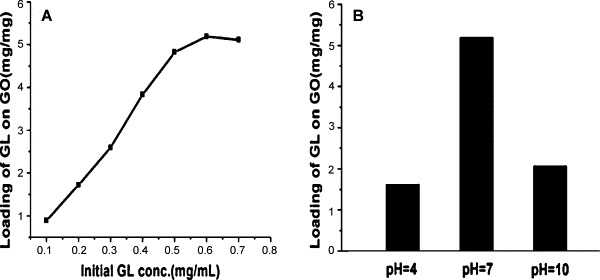

The loading of GL on GO was investigated in different initial GL concentrations at pH value of 7 with respect of the same concentration of GO, as shown in Fig. 6A. The loading of GL on GO is 0.89 mg/mg at the GL concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. With the increase of the initial GL concentration, the loading capacity of GL increases linearly and reaches highest value, 5.19 mg/mg, at a GL concentration of 0.6 mg/mL. Such a value of loading is far beyond the commonly used drug carrier materials, such as liposomes [10a], carbon nanohorns [16], polymer vesicles [17], and chitosan [10d], which are all below 1 mg/mg at saturated carrying concentration. The above results show that GO is indeed a promising candidate for drug carrier materials. The interaction between GO and GL comes from the strong hydrogen-bonding, furthermore, the overall structure of GL is catenarian which make the area of contact lower than deliveries with π-π staking interactions.

Fig. 6.

The loading capacity of GL on GO in different initial GL concentrations (A) and at different pH values (B). The concentration of GO is 0.1 mg/mL.

Fig. 6B shows the loading of GL on GO at the initial GL concentration of 0.6 mg/mL at pH values of 4, 7 and 10, respectively. As expected, the GO shows distinctly different loading capacity toward GL at different pH values. The maximum loading of GL on GO is 1.62 mg/mg at pH 4, 5.19 mg/mg at pH 7, and 2.07 mg/mg at pH 10. The highest loading capacity is observed at the neutral condition, rather than acidic or alkaline conditions.

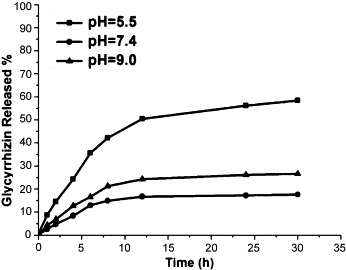

3.3. GL release test

The fate of a drug from a drug carrier depends on various experimental factors such as pH, degradation rate, particle size and interaction between drug. Here, the release behavior of GL from GO is shown in Fig. 7 . GL releases slowly from GO and the release rate gradually declines after 6 h and about 17.6% of the total bound GL was released from the nanohybrid in the first 30 h under neutral conditions (pH 7.4). As discussed above, the hydrogen-bonding interaction between GL and GO is the strongest under neutral condition, resulting in an inefficient release. The release behavior under acidic and alkaline conditions indicates that 58.4% and 26.6% of the total bound GL was released from the nanohybrid after 30 h at pH 5.5 and 9.0 in the first 30 h, respectively, which is much higher than that under neutral conditions. pH 5.5 resembles intracellular lysosomes, endosomes or cancerous tissues condition [18]. In lower pH, the H+ in solution would compete with the hydrogen-bond-forming groups and then weaken the hydrogen-bonding interaction interaction between GO and GL which resulting a higher release. Under alkaline condition, -COOH group both of GO and GL dissociates as -COO− and the force of hydrogen bond between GO and GL decreases, so the GL releases more easily than in the case of neutral condition. The pH-dependent drug release from GO could be exploited for drug delivery applications since the micro-environments of extra cellular tissues of tumors and intracellular lysosomes and endosomes are acidic, potentially facilitating active drug release from GO delivery vehicles [19].

Fig. 7.

The release of GL on GO at different pH values.

4. Conclusions

In this article, GO-GL has been prepared in order to develop a drug delivery system targeting the liver by the specific interaction between GL and hepatocytes. The GO-GL is obtained under mild conditions without any organic solvents and surfactants, which is very suitable for pharmaceutical applications. A high loading of GL on GO and a pH-dependent release behavior is observed. The pH-dependent loading and releasing was attributed to the hydrogen-bonding interactions between GO and GL. The results of loading and release experiments indicate that this system seems to be a very promising vehicle for loading of drugs under neutral conditions and releasing under acidic environment. This work can be considered as the first step for further study on the application of GO-GL as a promising carrier for possible drug delivery targeting the liver in vivo.

Acknowledgment

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (authorized number: 50802045, 20975056 and 81102411), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2011BZ004 and ZR2011BQ005), Natural Science Foundation of Qingdao (09-1-3-30-jch), Program of NSFC-JSPS (21111140014) and Taishan Scholar Ferrogram of Shandong Province (TS20070711), China.

Contributor Information

Zonghua Wang, Email: wangzonghua@qdu.edu.cn.

Yanzhi Xia, Email: qdxyzh@163.com.

References

- 1.(a) Aly A.M., Al-Alousi L., Salem H.A. Licorice. 2005;6:E74. doi: 10.1208/pt060113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ploeger B.A., Meulenbelt J., DeJongh J. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000;162:177. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crance J.M., Biziagos E., Passagot J., Cuyck-Gandre V.H., Deloince R. J. Med. Virol. 1990;31:155. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890310214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahara T., Watanabe A., Shiraki K. J. Hepatol. 1994;21:601. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(94)80108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arase Y., Ikeda K., Murashima N., Chayama K., Tsubota A., Koida I. Cancer. 1997;79:1494. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970415)79:8<1494::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito M., Sato A., Hirabayashi K., Tanabe F., Shigeta S., Baba M., Clercq E.D., Nakashima H., Yamamoto N. Antiviral Res. 1988;10:289. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(88)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nassiri-Asl M., Hosseinzadeh H. Phytother. Res. 2008;22:709. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stähli B.E., Breitenstein A., Akhmedov A., Camici G.G., Shojaati K., Bogdanov N., Steffel J., Ringli D., Lüscher T.F., Tanner F.C. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:2769. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Negishi M., Irie A., Nagata N., Ichikawa A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1066:77. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishida S., Sakiya Y., Ichikawa T., Taira Z. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1993;16:293. doi: 10.1248/bpb.16.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ismair M.G., Stanca C., Ha H.R., Renner E.L., Meier P.J., Kullak-Ublick G.A. Hepatol. Res. 2003;26:343. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(03)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Tsuji H., Osaka S., Kiwada H. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991;39:1004. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Osaka S., Tsuji H., Kiwada H. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1994;17:940. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mao S.J., Hou S.X., He R., Zhang L.K., Wei D.P., Bi Y.Q., Jin H., World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;28:3075. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lin A.H., Liu Y.M., Huang Y., Sun J.B., Wu Z.F., Zhang X., Ping Q. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;359:247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novoselov K.S., Geim A.K., Morozov S.V., Jiang D. Science. 2004;306:666. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Liu Z., Robinson J.T., Sun X., Dai H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10876. doi: 10.1021/ja803688x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang X., Zhang X., Liu Z., Ma Y., Huang Y., Chen Y. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:17554. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hummers W.S., R E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958;80:1339. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo Z., Du F., Ren D.M., Chen Y.S., Zheng J.Y., Liu Z.B., Tian J.G. J. Mater. Chem. 2006;16:3021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu X.Y., Yang Y.F., Ma Y., Huang Chen Y.S. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008;30:1031. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami T., Ajima K., Miyawaki J., Yudasaka M., Iijima S., Shiba K. Mol. Pharm. 2004;1:399. doi: 10.1021/mp049928e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choucair A., Soo P.L., Eisenberg A. Langmuir. 2005;21:9308. doi: 10.1021/la050710o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taghdisi S.M., Lavaeea P., Ramezanic M., Abnous K. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011;77:200. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z., Sun X.M., Nakayama-Ratchford N., Dai H.J. ACS Nano. 2007;1:50. doi: 10.1021/nn700040t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]