Summary:

The expression of multiple growth-promoting genes is coordinated by the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie with its major regulatory input provided by the Hippo/Warts kinase cascade. Here, we identify Atg1/ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of Yorkie as an additional inhibitory input independent of the Hippo/Warts pathway. Two serine residues in Yorkie, S74 and S97, are Atg1/ULK1 consensus target sites and are phosphorylated by ULK1 in vitro, thereby preventing its binding to Scalloped. In vivo, gain-of-function of Atg1, or its activator Acinus, caused elevated Yorkie phosphorylation and inhibited Yorkie’s growth promoting activity. Loss of function of Atg1 or Acinus raised expression of Yorkie target genes and increased tissue size. Unlike Atg1’s role in autophagy, Atg1-mediated phosphorylation of Yorkie does not require Atg13. Atg1 is activated by starvation and other cellular stressors and therefore can impose temporary stress-induced constraints on the growth-promoting gene networks under control of Hippo/Yorkie signaling.

Keywords: growth control, autophagy, Scalloped, Acinus

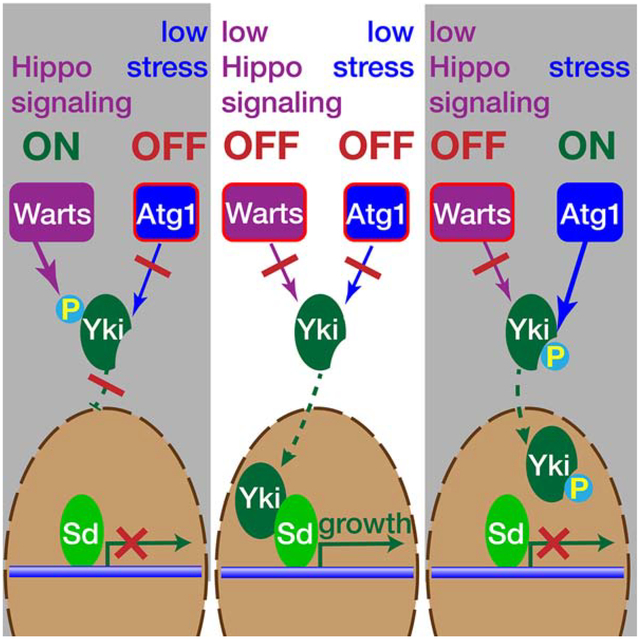

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

eTOC

During development or regeneration of Drosophila tissues, growth is promoted by the Yorkie transcriptional cofactor under control of the Hippo signaling pathway. Tyra et al. identify an additional pathway that can regulate Yorkie activity through Atg1-mediated phosphorylation, thereby constraining its activity under conditions of environmental stress.

Introduction:

A fundamental problem in developmental biology is how intrinsic mechanisms that determine growth and final tissue size are coordinated with temporary environmental challenges, such as nutrient deprivation. One major growth-regulating signaling pathway that includes the core Hippo/Warts kinase cascade and the Yorkie transcriptional co-activator was discovered by forward genetic screens in Drosophila (Hamaratoglu et al., 2006; Harvey et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005; Udan et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2003). The Hippo and Warts kinases receive diverse inputs reporting on the size and shape of tissues, cell contacts and the ensuing mechanical forces (Codelia et al., 2014; Halder et al., 2012; Hariharan, 2015). The major readout of this pathway is the Warts-mediated phosphorylation of Yorkie at three distinct serine residues, S111, S168, and S250, the most important one being S168 (Dong et al., 2007; Oh and Irvine, 2008; Zhao et al., 2007). Phosphorylated Yorkie binds to 14-3-3 proteins (Oh and Irvine, 2009; Ren et al., 2010), which sequesters Yorkie in the cytosol and thereby inhibits its function as growth-promoting transcriptional co-activator (Wu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). This pathway is highly conserved in vertebrates as well, with the Yorkie homologs YAP and TAZ as effectors of the core kinase cascade consisting of the MST1/2 and LTS1/2 kinases (Johnson and Halder, 2014; Plouffe et al., 2015). In addition to input from the canonical Hippo/Warts cascade, the activity of Yorkie and its mammalian homologs is also modified by other inputs responsive to diverse cellular stressors and metabolic changes (Mo et al., 2015; Nguyen et al., 2013; Santinon et al., 2016; Wehr et al., 2013; Zheng and Pan, 2019).

Acinus has emerged as a signaling node that integrates multiple cellular stress signals (Nandi and Kramer, 2018b). Acinus is a conserved subunit of the nuclear ASAP complex (Murachelli et al., 2012; Schwerk et al., 2003), that interacts with the exon junction complex and participates in alternative RNA splicing (Hayashi et al., 2014; Malone et al., 2014; Rodor et al., 2016). However, genetic experiments in Drosophila revealed a second role for Acinus as inducer of starvation-independent, basal autophagy (Haberman et al., 2010). Acinus levels and its pro-autophagy activity are promoted by stress-regulated kinases, including Cdk5, p38b MAP kinase, and Akt1, and suppressed by non-apoptotic caspase cleavage (Nandi et al., 2017; Nandi et al., 2014). The specific mechanisms by which Acinus promotes basal autophagy remain unclear, but an eye-specific Acinus gain-of-function model revealed a requirement for the Atg1 kinase (Nandi et al., 2014). This suggests Acinus may activate Atg1 by a starvation-independent pathway (Nandi and Kramer, 2018a).

Atg1, like its mammalian homologs ULK1/2, is a serine/threonine kinase that regulates multiple core autophagy proteins through phosphorylation (Egan et al., 2015; Papinski et al., 2014; Park et al., 2016; Russell et al., 2013; Wold et al., 2016). Thereby, Atg1 induces the formation of autophagosomes and promotes their maturation (Mizushima, 2010). Atg1-mediated activation of autophagy requires release from the mTor-imposed inhibitory phosphorylation of the Atg1/ULK1 complex (Egan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Shang et al., 2011; Zhao and Klionsky, 2011) and the engagement of Atg1 in a protein complex that contains Atg13, and FIP200/Atg17 and other species-specific cofactors (Lin and Hurley, 2016; Zachari and Ganley, 2017).

Here, we describe a role for Atg1 in phosphorylating Yorkie and the resulting inhibition of its growth-promoting activity. We identify two sites at S74 and S97, that match the previously described consensus motifs for Atg1 and ULK1 (Egan et al., 2015; Papinski et al., 2014) and are phosphorylated by ULK1 in vitro. In vivo, Atg1 or Acinus gain-of-function interfere with Yorkie’s growth promoting activity, whereas Atg1 or Acinus loss-of-function enhance expression of Yorkie target genes. These findings reveal a stress-induced mechanism that can inhibit Yorkie activity independently of the canonical Hippo/Warts pathway.

Results

Acinus and Atg1 suppress Yorkie activity

In the context of genetic screens aimed at identifying regulators of Acinus activity (Nandi et al., 2017; Nandi et al., 2014), we noticed suppression of the Acinus-induced rough eye by deficiencies removing genes in the Hippo/Yorkie pathway or by Hippo RNAi (Supplemental Figure S1A–F). Further testing of hippo null clones revealed, however, no changes in levels of Acinus or its phosphorylation on key regulatory sites (Supplemental Figure S1G–I). We therefore tested whether, alternatively, Acinus overexpression may alter signaling through the Hippo/Yorkie pathway. Eye-specific expression of the mutant YorkieS168A protein, which lacks its major Warts phosphorylation target, causes dramatic eye overgrowth (Figure 1A, B and Dong et al., 2007; Oh and Irvine, 2009). This phenotype was suppressed by co-expression of Acinus which resulted in a small rough eye (Figure 1C,D).

Figure 1. Acinus and Atg1 interact genetically with Yorkie gain-of-function.

(A-L) SEM images of eyes either expressing only GMR-Gal4 (A) or with GMR-Gal4 driving expression of UAS-YorkieS168A (B), UAS-Acn (C), UAS-YorkieS168A and UAS-Acn (D), UAS-Atg1 (E), UAS-YorkieS168A and UAS- Atg1 (F), UAS-Atg1K38Q (G), UAS-YorkieS168A and UAS-Atg1K38Q (H), UAS-Atg13 (I), UAS-YorkieS168A and UAS-Atg13 (J), UAS-Atg6 (K), UAS-YorkieS168A and UAS-Atg6 (L). Scale bar indicates 100 μm in A-L. All crosses were repeated at least three times. For quantification see Supplemental table S1.

(M) Quantification of the survival of flies expressing under GMR-Gal4 control either UAS-YorkieS111,168,250A alone or together with UAS-Acinus or UAS-Atg1. Scatter plot of average ratios between the indicated genotypes and the sibling controls lacking the GMR-Gal4 drivers (Atg1) or the UAS-YorkieS111,168,250A transgene (Acinus). Data are from three independent crosses per genotype with at least 140 flies each. Lines indicate means and standard deviations, (Student’s t-test: * p < 0.05,*** p<0.001).

See also Figures S1 and S2 and Tables S1. Detailed genotypes are listed in Table S2.

Acinus overexpression induces elevated autophagy levels (Haberman et al., 2010; Nandi et al., 2017). We therefore wondered whether expression of other autophagy genes yielded similar suppression of Yorkie-induced overgrowth. We found that YorkieS168A-induced eye overgrowth was also suppressed by co-expression of the Atg1 kinase (Figure 1E,F, Supplemental Table S1), but not the Atg1K38Q mutant (Figure 1G,H, Supplemental Table S1) which lacks kinase activity (Scott et al., 2007). Furthermore, co-expression of Atg13 (Figure 1I,J, Supplemental Table S1), an Atg1 cofactor for the induction of autophagy (Chang and Neufeld, 2009), or of Atg6 failed to suppress overgrowth induced by YorkieS168A (Figure 1K,L, Supplemental Table S1). Nevertheless, similar to Atg1 or Acinus (Nandi et al., 2017), GMR-Gal4-driven Atg6/Beclin1 overexpression was sufficient to induce elevated levels of Atg8a punctae in developing eye discs (Supplemental Figure S2), consistent with the known role of Atg6/Beclin1 as an inducer of autophagy (Levine et al., 2015).

To test whether Acinus and Atg1 act upstream of Yorkie on elements of the core Hippo/Warts pathway, we used the triple mutant UAS-YorkieS111,168,250A transgene. In this Yorkie mutant the three known target sites for Warts phosphorylation are mutated, thereby largely insulating Yorkie from input of the Hippo and Warts kinases and resulting in excessive tissue overgrowth and greatly reduced viability upon GMR-Gal4-driven expression (Oh and Irvine, 2009). Lethality of YorkieS110,168,250A expression was, however, effectively suppressed by Acinus or Atg1 co-expression (Figure 1M), indicating that both acted to suppress Yorkie activity independently of the upstream elements of the core Hippo/Warts pathway.

To test whether the Atg1/Acinus-mediated suppression reflects changes in the expression of downstream elements of the Hippo/Yorkie pathway, we explored expression of previously established Yorkie target genes (Hamaratoglu et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2005; Jia et al., 2003; Nolo et al., 2006; Ryoo et al., 2002; Thompson and Cohen, 2006; Zhang et al., 2008). Elevated expression of bantam, as detected by a ban-lacZ transcriptional reporter in the endogenous locus (Herranz et al., 2012), was induced in eye discs posterior to the furrow upon GMR-Gal4-driven YkiS168A expression (Figure 2A,B). This increase was suppressed when Atg1 was co-expressed (Figure 2C). Similarly, GMR-Gal4-driven YkiS168A expression increased the levels of Expanded (Ex) (Figure 2D,E) and Diap1/Thread (Figure 2G,H). Their induction was suppressed, however, when Atg1 was co-expressed with YkiS168A (Figure 2F,I). Furthermore, clonal expression of Yki in wing discs triggered neoplastic growth (Oh and Irvine, 2008) with elevated levels of Ex and Diap1 (Figure 2J,K,N,O). Co-expression of Atg1 resulted in smaller clones with reduced Ex and Diap1 levels (Figure 2L,M,P,Q).

Figure 2. Atg1 overexpression suppresses Yorkie target genes.

(A-I) Confocal images of third instar eye discs stained for the ban-LacZ reporter (A-C) or for endogenous Ex (D-F) or Diap1 (G-I) proteins. All larvae contained the GMR-Gal4 driver and, as indicated, expressed only UAS-YkiS168A (B,E,H) or UAS-YkiS168A together with UAS-Atg1 (C,F,I). Arrowheads indicate the morphogenetic furrow. Posterior is to the right.

(J-Q) Confocal images of third instar wing discs stained for endogenous Ex (J-M) or Diap1 (N-Q) proteins. Clonal expression of UAS-GFP and UAS-Yki without (J,K,N,O) or together with UAS-Atg1 (L,M,P,Q) was driven from a Gal4-Act5C(FRT.CD2) cassette upon hsFLP-mediated activation. Images are representative examples from at least three independent crosses with 5 or more examples each.

Scale bars in A = 50 μm (A-I), in J = 100 μm (J-Q). Detailed genotypes are listed in Table S2.

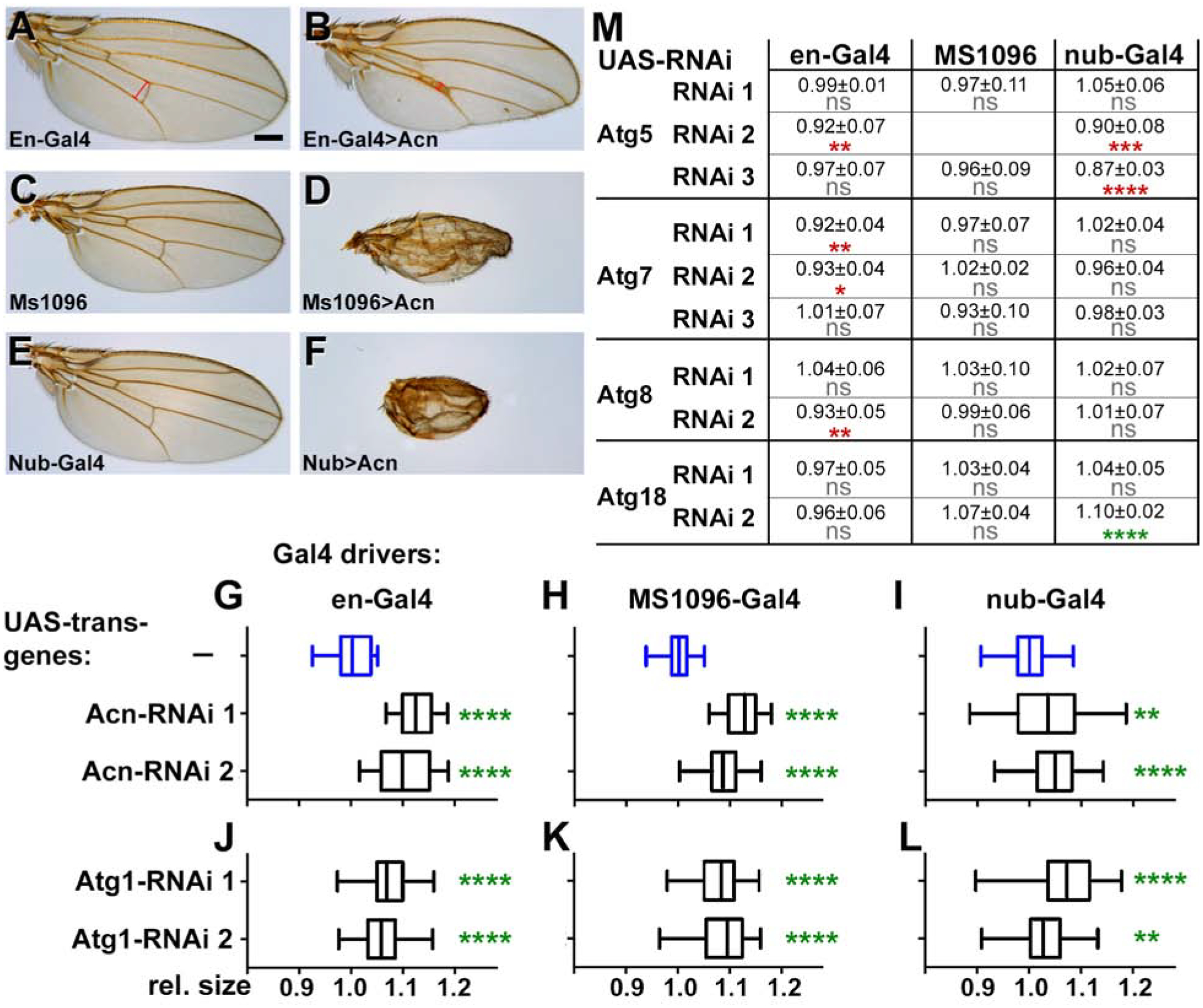

Next, we tested whether the genetic interactions we observed with these yorkie gain-of-function models extended to endogenous yorkie as well. The size of Drosophila wings is sensitive to modulation of endogenous Yorkie activity thus offering a convenient model to interrogate changes in the level of Yorkie activity (Harvey et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2005; Nolo et al., 2006). Overexpression of Acinus with the en-Gal4 driver reduced the size of the posterior wing compartment (Fig. 3A,B). Effects on wing size caused by Acinus overexpression in the wing pouch using nubbin-Gal4 or MS1096-Gal4 drivers were more difficult to evaluate due to the severe morphological changes (Figure 3C–F). Atg1 overexpression with these drivers caused similarly severe wing deformation or even lethality.

Figure 3. Loss or overexpression of Acinus and Atg1 alter adult wing size.

(A-F) Micrographs of wings expressing only the indicated Gal4 drivers as controls (A,C,E) or UAS-Acn driven by those drivers (B,D,F). Scale bar = 200 μm.

(G-L) Box and whisker plots display adult wing sizes of flies expressing the indicated UAS-RNAi transgene targeting Acinus (G-I) or Atg1 (J-L) under the control of the indicated wing drivers: en-Gal4 (G,J), MS1096-Gal4 (H,K), or nubbin-Gal4 (I,L). Data are from 3 independent crosses with at least 15 wings per genotype. See example images in Figure S3.

(M) Table of wing sizes from flies with the indicated RNAi transgenes and Gal4 drivers. Data are from 3 independent crosses with 15 wings per genotype and displayed as mean ± standard deviation. ns: not significant, * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), or **** (p < 0.0001). Green stars indicate significantly increased, and red stars significantly decreased wing sizes.

Detailed genotypes are listed in Table S2.

Acinus or Atg1 loss-of-function experiments in the wing were more informative. Expression of two RNAi transgenes each for Acinus or Atg1 in different wing domains using three different Gal4 drivers (en-Gal4, nubbin-Gal4 and MS1096-Gal4) consistently increased wing size compared to control flies with only the Gal4 driver (Figure 3G–L, Supplemental Figure S3). Additionally, knockdown of Atg1 partially suppressed the lethality caused by Yki-RNAi. While 0% of the expected number of flies emerged when Yki-RNAi was expressed under control of the en-Gal4 driver, coexpression of Atg1-RNAi partially suppressed this lethality and yielded 15% of the expected adults.

By contrast to our findings with Atg1 and Acinus, knockdown of the core autophagy genes Atg5, Atg7, Atg8 or Atg18 did not consistently alter wing size (Figure 3M). With the single exception of Atg18 RNAi driven by nubbin-Gal4, wing sizes decreased as opposed to the increase observed with Acinus or Atg1 knockdown. Together these experiments suggest that Acinus and Atg1 alter Yorkie-dependent growth control during eye and wing development, but in a manner independent of their role in inducing autophagy.

Acinus and Atg1 regulate Yorkie-dependent transcription

We next tested whether the changes in wing sizes in response to Atg1 and Acinus knockdown are reflected in altered expression of Yorkie target genes. As a positive control we knocked down Hippo using the en-Gal4 driver. Consistent with previous reports of bantam as Yorkie target gene (Nolo et al., 2006; Thompson and Cohen, 2006), we observed elevated ban-lacZ expression within the posterior compartment marked by UAS-mCherry expression (Fig. 4A,B). Importantly, knockdown of Atg1 or Acinus also resulted in elevated ban-lacZ levels in the posterior wing (Figure 4C,D). Similarly, knockdown of Hippo, Atg1 or Acinus using the en-Gal4 driver resulted in increased expression of Diap1 (Figure 4E–H) and Expanded (Figure 4I–L) in the posterior wing, consistent with Atg1 and Acinus regulating the expression of these Yorkie target genes. These findings support the model that the genetic interactions of yorkie with acinus and atg1 reflect their direct effect on Yorkie-mediated transcriptional activity.

Figure 4. Loss of Acinus or Atg1 enhances expression of Yorkie target genes.

Confocal images of third instar wing discs stained for the ban-LacZ (A-D) reporter of Yorkie transcriptional activity, or the endogenous Diap1 (E-H) and Ex (I-L) proteins. All larvae contained the en-Gal4 driver and only UAS-mCherry (A,E,I), or, in addition, the indicated UAS-RNAi transgenes knocking down Hippo (B,F,J), Atg1 (C,G,K) or Acinus (D,H,L). The mCherry-marked posterior en-Gal4 expression domains are shown in (A’-L’). Images are representative examples from at least three independent crosses with 5 or more examples each. Scale bar = 100 μm. Detailed genotypes are listed in Table S2.

Atg1 phosphorylates Yorkie in vitro

Recent work in yeast and mammalian cells has established consensus motifs for Atg1/ULK1-dependent phosphorylation (Egan et al., 2015; Papinski et al., 2014). We identified two sites in Yorkie that match these motifs (Figure 5A). Consistent with the partial conservation of these sites, purified ULK1 kinase phosphorylated TAZ or YAP1 proteins in vitro (Figure 5B). To test the two sites individually, purified GST-Yorkie53−119 fusion proteins, either wild type or mutants with the potential phosphorylation targets S74 or S97 individually or both changed to alanines, were exposed to purified ULK1 kinase and ATP. Site-specific phospho-Yorkie antibodies revealed phosphorylation at both sites (Figure 5C). In these in-vitro assays, phosphorylation at S74 induced a shift in mobility (red arrows) that affected a substantial fraction of the fusion protein and is dependent on the presence of S74 (Figure 5C). Previous work has indicated that YAP and TAZ require the serine residue equivalent to S97 for binding to TEAD (Chen et al., 2010; Kaan et al., 2017; Li et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2010). Similarly, S97 is required for GST-Yorkie53−119 binding to the Scalloped transcription factor (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, phosphorylation of S97, but not S74, prevented GST-Yorkie53−119 binding to Scalloped (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5: Atg1/ULK1 phosphorylates serine residues 74 and 97 of Yorkie.

(A) Diagram of Atg1 target consensus sequence, compared to potential phosphorylation sites at serines 74, and 97 in Yorkie and corresponding sites in human and mouse YAP and TAZ proteins.

(B) Auto-radiogram of in-vitro kinase assay shows phosphorylation of YAP1, and TAZ by ULK1.

(C) Western blots of purified wild-type (WT) or S74A, S97A, or S74,97A mutant GST-Yki53−119 fusion proteins incubated with or without purified ULK1. Blots were developed with antibodies against GST (1:10,000), pS74-Yki (1:5,000), pS97-Yki (1:1,000). Red arrows indicate mobility shifts for S74-phosphorylated GST-Yki proteins.

D) Western blots of wild-type (WT) or S74A, S97A, or S74,97A mutant GST-Yki53−119 fusion proteins bound to MagStrep beads without (−) or with immobilized Twin-Strep-tagged Myc-Sd protein (+). Proteins bound to the beads or found in flow-through were developed with antibodies against GST (1:1,000) or Myc (1:2,000).

E) Western blots of wild-type GST-Yki53−119 incubated with or without purified ULK1 and bound to bead-immobilized Twin-Strep-tagged Myc-Sd protein. Proteins eluted from Myc-Sd-beads or found in flow-through were detected with antibodies against Myc (1:2,000), GST (1:1,000), pS74-Yki (1:2,000), or pS97-Yki (1:400). Western blots are representative images from three repeats.

(F-H) Confocal micrographs of fat body cells. A ykiB5 clone (−/−) marked by the absence of GFP (F’) lacks pS74 Yorkie staining (F). (G) Starved wild-type fat bodies exhibit nuclear pS74-Yorkie staining, which is missing in the CRISPR/Cas9-generated ykiS74A allele (H). Nuclei are shown in (G’ and H’). Scale bar = 50 μm.

See also Figure S4. Detailed genotypes are listed in Table S2.

To test the importance of these residues in vivo, we first compared eye overgrowth induced by GMRGal4-driven UAS-YorkieS168A and UAS-YorkieS74,168A transgenes, both lacking the major Warts phosphorylation site. Both were able to induce eye overgrowth (Supplemental Figure S4A,B) indicating that serine 74 is not necessary for Yorkie’s function. Furthermore, for both of these transgenes eye overgrowth was suppressed by co-expression of either Acinus or Atg1 (Supplemental Figure S4D,E,G,H). By contrast, the triple mutant transgene UAS-YorkieS74,97,168A expressed under GMR-Gal4 control was not able to induce eye-overgrowth (Supplemental Figure S4C). This is consistent with the previously established requirement of the corresponding residue for YAP binding to the TEAD transcription factor (Li et al., 2010) and with our in-vitro binding studies pointing to the critical role of S97 (Figure 5D,E).

Atg1 phosphorylates Yorkie in vivo.

Next, we tested whether the antibodies directed against either of these phosphorylation sites was suitable for in-vivo analysis. First, we generated ykiB5 loss-of-function clones in fat bodies (Figure 5F). While we could not detect any specific staining with the pS97-Yorkie antibody, staining with the pS74-Yorkie antibody was specific as indicated by the severely reduced signal in ykiB5 null clones (Figure 5F). Furthermore, using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-directed mutagenesis, we generated two mutant yki alleles in which either S74 alone or S74 and S97 were mutated in the endogenous gene. Homozygous ykiS74,97A mutants were lethal. This is consistent with importance of S97 for Yorkie function described above (Figure 5D,E, Supplemental Figure S4) and the equivalent residue for YAP and TAZ function (Chen et al., 2010; Kaan et al., 2017; Li et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2010). By contrast, homozygous ykiS74A flies were viable and ykiS74A fat bodies showed substantially reduced staining with the pS74-Yorkie antibody (Figure 5 G,H), further indicating that, except for unspecific staining of mitotic cells in imaginal discs (Supplemental Figure S5, A–D) pS74-Yorkie staining is specific.

Atg1 kinase activity is induced by multiple pathways. First, we tested amino acid starvation, which regulates Atg1 in a Tor-dependent manner (Jung et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2007). In starved 96-hr larval fat bodies, pS74-Yorkie staining was elevated in many but not all cells (Figure 6A,B) without consistent changes in Yorkie levels. Starvation-induced Yorkie-phosphorylation was independent of hpo activity (Figure 6F). In fat bodies of fed larvae, phosphorylation of Yorkie S74 was cell-autonomously elevated by clonal expression of Atg1 (Figure 6C) or Acinus (Figure 6D), but not RFP in control clones (Figure 6E), and without a proportional increase in total Yorkie levels (Figure 6C”–E”). Similarly, Yorkie S74 phosphorylation was observed in some, but not all cells of Atg1 overexpressing clones in wing discs (Supplemental Figure S5E–H).

Figure 6. Atg1 phosphorylates Yorkie in vivo.

Micrographs show confocal projections of fat bodies from fed (A,C,D,E) or starved (B,F-N) third instar larvae stained for DNA and the indicated antigens.

(A,B) In wild-type fat bodies staining for pS74-Yorkie, but not Yorkie, was enhanced by starvation. (C-E) Atg1 (C) and Acinus (D) overexpressing clones are marked by co-expressed RFP, (E) shows an RFP overexpressing control clone.

(F-H) Homozygous loss-of-function clones (−/−) for hpoKS240 (F), Atg1D3D (G) or acn27 (H) are marked by loss of GFP or lacZ as indicated and show no requirement of hpo (F) for pS74-Yki staining, in contrast to Atg1 (G) or acn (H).

(I,J) RNAi-expressing clones marked with RFP, show reduced pS74-Yki staining upon knockdown of Atg1 (I) or Acn (J).

(K) In cells of starved wild-type fat bodies, variable levels of Acinus staining parallel differences in pS74-Yki staining.

(L,M) Loss-of-function clones for atg1381 (−/−) show that it is required for starvation-induced Atg8-positive autophagosomes (K’), but dispensable for pS74-Yki phosphorylation.

(N) Knockdown of AMPK does not alter pS74-Yki staining.

Images are representative examples from at least three independent crosses with 5 or more examples each.

Scale bar in A: 50 μm for A-M and 100 μm for N.

See also Figure S5. Detailed genotypes are listed in Table S2.

Cells positive for pS74-Yorkie were not observed within Atg1 or Acinus loss-of-function clones (Figure 6G–J). Furthermore, pS74-Yorkie phosphorylation in starved wild-type fat bodies closely paralleled the levels of endogenous Acinus protein (Figure 6K). These findings are consistent with both Acinus and Atg1 being required for Yorkie S74 phosphorylation. This differed, however, for Atg13 which is required as cofactor of Atg1 in the formation of ATG8-positive autophagosomes (Figure 6L). Interestingly, Atg13 is not required for Yorkie-S74 phosphorylation in starved fat bodies (Figure 6M). Similarly, knockdown of AMP-activated kinase, which can activate Atg1 in response to metabolic stress (Egan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011), did not interfere with pS74-Yorkie phosphorylation (Figure 6N). Together, these data indicate that a distinct, AMPK/Atg13-independent but Acinus-dependent pool of Atg1 kinase phosphorylates Yorkie and regulates its activity.

Discussion

The Hippo/Yorkie pathway plays a critical role in regulating tissue growth during development and regeneration. Here, we describe a mechanism for the integration of this pathway with the temporary constraints imposed by environmental conditions. We find that stress-activated Atg1/ULK kinases phosphorylate Yorkie in vitro and in vivo. Two target sites identified were serine residue S74 and S97. Unlike the cytosolic sequestration initiated by Warts phosphorylating Yorkie (Oh and Irvine, 2008), Atg1-mediated phosphorylation does not interfere with Yorkie’s nuclear localization, but nevertheless inhibits expression of Yorkie downstream targets and thereby interferes with tissue growth.

Inhibition of Yorkie activity, despite increased nuclear accumulation, was previously observed in response to inhibition of TOR activity (Parker and Struhl, 2015). In that study, however, no direct phosphorylation of Yorkie by TOR was reported. Interestingly, TOR and Atg1/ULK kinases mutually inhibit each other’s activity (Egan et al., 2011; Jung et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Shang et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2013; Zhao and Klionsky, 2011). Thus, in the light of our findings, TOR-mediated activation of Yorkie may be explained by Tor’s inhibitory effect on Atg1. This in turn would relieve the Atg1-mediated inhibition of Yorkie.

Hippo/Warts-independent regulation of Yorkie has also been observed in response to activation of LKB1 and its downstream target AMPK in the Drosophila CNS (Gailite et al., 2015). By contrast, we find that starvation-induced Yorkie phosphorylation in fat bodies is independent of AMPK. It is intriguing to note that AMPK in mammalian cells can induce phosphorylation of S94 of YAP, the residue that corresponds to S97 of Yorkie (Mo et al., 2015). Our in-vitro data show that this site is targeted by Atg1/ULK kinases, but our current tools were not adequate to assess the level of S97 phosphorylation in tissues. The regulatory importance of this conserved residue reflects its central role in the interaction of Yorkie/YAP/TAZ transcriptional co-activators with the Scalloped/TEAD transcription factors. In YAP/TEAD or TAZ/TEAD complexes, the hydroxyl group of YAP-S94/TAZ-S51 is placed to form hydrogen bonds with conserved tyrosine and glutamate residues in TEAD proteins (Chen et al., 2010; Kaan et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2010). Thus, not surprisingly, mutating as well as phosphorylating this serine in YAP (Chen et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010) or Yorkie (Zhao et al., 2008)(Figure 5, Supplemental Figure S4) interferes with their function. The strict requirement of this serine residue for Yorkie function thus prevented us from using a YorkieS97A mutation to further test the specific role of S97 phosphorylation in the epistatic interactions between Atg1 and Yorkie.

The importance of Yorkie-S74, the second site phosphorylated by Atg1, is less clear. This serine is conserved in TAZ but not in YAP homologs of Yorkie. Furthermore, we found that replacement of this serine with alanine in the endogenous yorkie gene by CRISPR/Cas9-induced homology-directed repair yielded the yorkieS74A allele that was homozygous viable and lacked any overt phenotype. In the TAZ/TEAD complex the corresponding TAZ-S34 appears not to be directly engaged in TEAD binding (Kaan et al., 2017) and phosphorylation of Yorkie-S74 does not interfere with its binding to Scalloped (Figure 5E).

A key aspect of Yorkie-mediated growth control is its regulation by multiple negative feedback loops that maintain homeostasis. Yorkie enhances the expression of several tumor suppressors, including Ex, Kibra, Warts and Crumbs, which act as upstream negative regulators of its own activity (Genevet et al., 2010; Hamaratoglu et al., 2006; Jukam et al., 2013; Zheng and Pan, 2019). In that light, it is interesting to consider Yorkie-driven expression of Diap1, an inhibitor of caspase activity (Abrams, 1999). While this is generally considered to be part of the anti-apoptotic function of Yorkie, it is important to note that caspase function is not confined to apoptosis (Miura, 2012). For example, we have previously demonstrated that Acinus is cleaved and inactivated by the caspase Dcp-1 in non-apoptotic cells of fat bodies and imaginal discs (Nandi et al., 2014) and a recent report documented a role for caspase-mediated cleavage of Acinus in regulating imaginal tissue growth (Shinoda et al., 2019). Together, these data suggest that Yorkie-driven Diap1 expression may initiate a previously unappreciated negative feedback loop consisting of the inactivation of Dcp-1, the resulting disinhibition of Acinus, ultimately promoting Atg1-mediated inhibitory Yorkie phosphorylation. The mechanism by which Acinus activates Atg1 remains unclear, however.

In addition to the canonical function of Atg1 kinase and its orthologs as major regulators of autophagy, an increasing number of non-canonical, autophagy-unrelated substrates have emerged (Wang and Kundu, 2017). For example, a function in axonal transport, first observed in C. elegans for the unc-51 homolog of Atg1 (Ogura et al., 1994), was also observed in flies and mammals (Toda et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2017). Furthermore, ER-to-Golgi trafficking (Joo et al., 2016) and Rab5-mediated endocytosis (Tomoda et al., 2004) have been identified as additional functions related to autophagy-independent membrane trafficking. To which extent the substrates in these different contexts are targeted by distinct pools of the Atg1 kinase is not clear. It is thus interesting to note that Yorkie phosphorylation by Atg1, unlike autophagy induction, is independent of its cofactor Atg13 (Alers et al., 2014). An Atg13-independent role for Atg1 has previously also been described for the degradation of Drosophila salivary glands (Nandy et al., 2018). Understanding the possible role that Acinus plays in promoting the activity of distinct Atg1 pools is an important goal of our ongoing work.

STAR*METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Helmut Kramer (helmut.kramer@utsouthwestern.edu). All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restriction.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Drosophila Strains

Fly stocks were maintained at room temperature on standard cornmeal molasses-yeast food supplemented with dry yeast unless stated otherwise. For all SEM images of adult eyes, only females were used because of their typically larger size. For all other experiments, males and females were used indiscriminately without analysis of gender-specific effects.

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center provided OreR, w1118, and Gal4 driver lines (BS 30557, BS 25754 -Dcr-2 was removed from this line before use, BS 8860, BS 1104), the following transgenes: UAS-Atg1 (BS 51655), y[1] w[*]; P{UAS-YkiS168A.GFP.HA} (BS 28836), w[*]; P{UAS-yki.S111A.S168A.S250A.V5}attP2 (BS 28817), P[hsFLP]1, y1w1118; Dr1/TM3, Sb1 (BS 7), P[hsFLP]1, w1118; Adv1/CyO (BS 6), and w1118; P[GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P]S, P[UAS-RFP.W]3/TM3, Sb1 (BS 30558), P{ry[+t7.2]=hsFLP}12, y[1]w[*]; P{ry[+t7.2]=neoFRT}42D. hpo[KS240]/CyO (BS 25085), w[1118]; P{ry[+t7.2]=neoFRT}42D P{w[+mC]=Ubi-GFP(S65T)nls}2R/CyO (BS 5626) and deficiency stocks listed in Supplemental Figure 1. RNAi lines were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and Vienna Drosophila Resource Center. Other fly strains used were: M{UAS-Atg6.ORF.3xHA.GW}ZH-86Fb (FlyORF), UAS-Acn-wt (Nandi et al., 2017), ubi-GFP acn27ubi-GFP FRT40A (Haberman et al., 2010), UAS-Atg13-FLAG, UAS-myc-Atg1, UAS-myc-Atg1K38Q (Chang and Neufeld, 2009), yw, hsFLP; Atg1 3D FRT80B/TM6B (Scott et al., 2004) [gift from Tom Neufeld], FRT42D ykiB5/CyO, P{ry[+t7.2]=hsFLP}1, w[1118]; P{w[+mC]=GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S, P{w[+mC]=UAS-GFP} (Huang et al., 2005), en-Gal4,UAS-m-Cherry/CyO, hsFLP; FRT40A LacZ, hsFLP; FRT80B, UAS-GFP, UAS-Yorkie/CyO, yw; Sp/CyO; ban-LacZ/TM6B, Tb1 (Herranz et al., 2012) [gift from DJ Pan], hsFLP; r4-Gal4 FRT82B UAS-GFP-nls, FRT82B Atg1381/TM6B (Mukherjee et al., 2016) [gift from Andreas Jenny]. Experiments with UAS-RNAi transgenes were performed at 28°C to maximize knockdown efficiency and all other crosses were performed at 25°C. AMPK RNAi knockdown clones in fat body were generated using hsFLP; Actin>CD2>Gal4, UAS-GFP exposing 3-day old larvae to a heat shock for 15 min at 38°C. All other overexpression and RNAi knock-down clones in fat body were generated by heat shocking larvae carrying hsFLP; Actin>CD2>Gal4, UAS-RFP and the indicated UAS-transgenes at 38°C for 1 hour the day prior to dissection. Atg1 over-expression clones in wing discs were generated by heat shocking 3-day old larvae containing hsFLP; Actin>CD2>Gal4, UAS-GFP and indicated UAS-transgenes at 38°C for 30 mins and expressing the transgene for 24 h at room temperature. hsFLP-induced mutant clones were generated as described (Liu et al., 2016).

UAS-Yorkie transgenes were generated by standard cloning in a pAttB-UAS vector for site-specific insertion. Specific mutations were introduced through standard mutagenesis or Gibson assembly of gBlocks (IDT, Coralville, Iowa), sequence-verified and inserted into the AttP landing sites at 43A1. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of Yorkie were performed as described (Stenesen et al., 2015) using tools available from the O’Connor-Giles, Wildonger, and Harrison laboratories (www.flycrispr.wisc.edu). Two guide RNAs located 5’ to the Yorkie coding sequences and 3’ to S97 (gRNA1: GTCGGCTGCACCTGCGGAATGCC and gRNA2: GTCGGGAGTGATGTATCGCCAGG) were introduced into the pCDF3-dU6 vector and co-injected with the appropriate template plasmid for homologous repair. Template plasmids were assembled in a pBluescript backbone from a 1kb PCR-amplified 5’ homology arm, and gBlocks (IDT, Coralville, IA) encoding an N-terminal modified 3xFLAG-tag (GDYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYNDHD), and WT, S74A, or S74,97A mutant Yorkie sequences, and a 910 bp 3’ homology arm. Embryo injections were done by Rainbow Transgenic Flies (Camarillo, CA), and the resulting potentially chimeric adult flies were crossed with balancer stocks. Their progeny, potential founders, were crossed again to balancer stocks and genotyped using a single-fly PCR preparation to identify lines containing germ-line Flag-Yorkie using a forward primer within the newly introduced FLAG-tag (GATTACAACGACCACGACGA) and a reverse primer complementary to newly introduced silent mutations 3’ to the serine S97 (ATGGAGCTGGTGGTGTGAAG). Genomic regions surrounding the Yorkie locus, outside the homology arms of the CRISPR Yorkie homology template plasmids, were amplified and sequenced to verify the correct editing of the Yorkie locus.

METHOD DETAILS

Wing measurement

Wings were removed from adult female flies at least one to three days post eclosion, dehydrated in 75% ethanol, placed on glass slides, mounted with Permount (Fisher) and a 1.5 coverslip, and dried on a slide warmer at 65°C. Wings were imaged using a Zeiss Discovery Stereoscope and quantified using area measurement in ImageJ as previously described (Rauskolb et al., 2011).

Immunofluorescence Staining

Whole-mount tissues were fixed and stained as described (Akbar et al., 2011). Fed and starved 96-h fat bodies were collected and stained as described (Nandi et al., 2017).

Fluorescence images were captured with 63× (NA 1.4) or 40× (NA1.3) or 20X (NA 0.75) lenses on an inverted confocal microscope (LSM710 or LSM510 Meta; Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Confocal Z-stacks of tissues were collected at a 1-μm step size and processed using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop.

Antibodies used: Mouse anti-Diap1 (1:1,000, gift from DJ Pan), Rabbit anti pS74 Yorkie (1:500), Chicken anti-GFP (1:500) from Aves and Chicken anti-β-Gal (1:1000) from Abcam, Guinea pig anti-Acinus (1:1000, Haberman et al., 2010), Rabbit anti-pS641-Acn (1:500, (Nandi et al., 2014)), Rabbit anti-pS437-Acn (1:500, (Nandi et al., 2017)), Rabbit anti-GABARAP which detects Drosophila melanogaster ATG8a (1:100, (Nandi et al., 2017)), Guinea pig anti-Yorkie (1:400, gift from Iswar Hariharan), Guinea pig anti-Expanded (1:5000, gift from Richard Fehon (Su et al., 2017)).

Scanning Electron Microscopy

SEM of fly eyes were obtained using standard methods as described (Wolff, 2011) (Nandi et al., 2014) with a Zeiss Sigma Scanning Electron Microscope with the InLens detector and an EHT of 3.0kV.

In Vitro Kinase assays

Radioactive in-vitro kinase assays were performed as described (Karra et al., 2017). Briefly, 400 ng of substrate (YAP1 or TAZ) were incubated with 100 ng of kinase ULK1 in kinase assay buffer (10mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 10 M ATP (5 Ci of [γ−32P]ATP {Perkin Elmer, Cat#NEG002A100UC} per reaction), 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate) for 1 h at 30°C. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and de-stained overnight. The gel was then dried on a Whatman 3MM Chr Chromatography paper (GE Healthcare) pre-soaked in methanol in a gel dryer at 80°C for 90 mins. Incorporation of 32P-phosphate was detected by autoradiography. Proteins used were human ULK1 (Sigma product number: SRP5096 Lot: G1163–1), human TAZ (OriGene Technologies product number: TP304082 Lot: 1160CA), and human Yap1 (OriGene Technologies product number: TP325864 Lot: 10a73e).

Non-radioactive phosphorylation of GST fusion proteins was performed as described (Nandi et al., 2017). In brief, immobilized GST-Yki53−119 fusion proteins were exposed to 50 ng ULK1 (Sigma Aldrich) in 100 μl kinase assay buffer (25 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 12. 5mM glycerol 2-phosphate, 25 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 2mM EDTA, 0.25 mM DTT, and 0.5 mM ATP) for 30 min at 30°C. Immobilized GST-Yorkie proteins were washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X100, eluted with 20 mM glutathione and analyzed by western blots using antibodies against pS74-Yorkie (1:2000), pS97-Yorkie (1:400), or GST (1:10,000) for detection of total GST-Yorkie proteins. Rabbit anti pS74 Yorkie against the sequence (DDNLQALFD-(p)S-VLNPGDAKR) and anti pS97 Yorkie against the sequence (RMRKLPN-(p)S-FFTPPAPS) were generated by Genemed Synthesis (San Antonio).

Yki binding assays

4 μg of pMT-TST-Myc-Sd encoding TwinStrep-Myc-tagged Sd under metallothionein promoter control (sequence available upon request) was transfected into 107 S2 cells using TransIT-2020 (Mirus, MIR5404) following the manufacturer’s instructions. 16 hours following induction with CuSO4 (0.7 mM), S2 cells were lysed by sonication in 100 mM Tris-Cl pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, including protease inhibitors (Roche, Cat#05892970001). Sd was bound to MagStrep “type3” XT beads (iba Cat#2-4090-002) followed by three washes with lysis buffer. 500 ng GST-Yki53−119 fusion proteins (wt, S74A, S97A, S74,97A) with or without phosphorylation using 50 ng Ulk1 (as described above) were incubated with Sd-bound beads for 1 h. Beads were washed 3 times in lysis buffer and proteins eluted using 1X Laemmli SDS buffer at 100°C. For western blots, Nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 μm, Amersham Protran) were cut in half just below the ~41kDa marker and blocked in 4% BSA. The upper half was used for detection of Myc-Sd (Mouse anti-myc 9E10; DSHB)) and the lower half was probed with mouse anti-GST (Thermo Fisher, MA4–004), rabbit anti-Yki-pS97, and rabbit anti-YkipS74 (Genemed Synthesis). Secondary antibodies used in conjunction with a Li-Cor Odyssey scanner were goat anti-mouse IR Dye 700DX (Odyssey 926–32510) and goat anti-rabbit IR Dye 800CW (Odyssey 926–32211).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical significance of survival assays was determined in Prism (GraphPad) using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Graphs resulting from these analysis show means ± SD. P-values smaller than 0.05 are considered significant, and values are indicated with * (<0.05), ** (<0.01), *** (<0.001), or **** (<.0001). For wing measurements, replicates were done in sets of 15 wings per set, with 3–4 replicates for each genotype. Measurements were normalized to Gal4-driver only controls and statistical significance was determined in Prism (GraphPad) using oneway ANOVA for multiple comparisons, followed by Tukey’s test. P-Values smaller than 0.05 are considered significant and values are indicated as * (<0.05), ** (<0.01), *** (<0.001), or **** (<.0001).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

This study did not generate data sets or code.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Goat anti-Mouse-IgG Alexa Fluor 405 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-31553, RRID: AB_221604 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit-IgG Alexa Fluor 405 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-31556; RRID:AB_22160 |

| Goat anti-Mouse-IgG Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32723; RRID:AB_2633275 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit-IgG Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32731; RRID:AB_2633280 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit-IgG Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32733; RRID:AB_2633282 |

| Goat anti-Mouse-IgG Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A32728; RRID:AB_2633277 |

| Goat anti-Guinea Pig-IgG Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11073; RRID:AB_2534117 |

| Goat anti-Guinea Pig-IgG Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11075; RRID:AB_2534119 |

| Goat anti-Guinea Pig-IgG Alexa Fluor 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-21450; RRID:AB_2735091 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11004; RRID:AB_2534072 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A-11036; RRID:AB_10563566 |

| anti-GST (mouse monoclonal) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#:MA4–004; RRID:AB_10979611 |

| anti-Acn (aa 423–599) (guinea pig polyclonal) | (Haberman et al., 2010) | N/A |

| anti-Myc 9E10 (mouse monoclonal) | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | DSHB:9E10; RRID:AB_2266850 |

| anti-GABARAP (rabbit monoclonal)) | Abcam | Cat#:ab109364; RRID:AB_10861928 |

| anti-GFP (chicken monoclonal) | Aves | Cat#:GFP-1020; RRID:AB_2307313 |

| anti-pS74-Yorkie (rabbit polyclonal) | This work; Genemed Synthesis | N/A |

| anti-pS97-Yorkie (rabbit polyclonal) | This work; Genemed Synthesis | N/A |

| anti-pS437-Acinus (rabbit polyclonal) | Genemed Synthesis (Nandi et al., 2017) | NA |

| anti-pS641-Acinus (rabbit polyclonal) | Genemed Synthesis (Nandi et al., 2014) | NA |

| anti-Yorkie (guinea pig polyclonal) | gift from Iswar Hariharan | N/A |

| anti-Diap-1 (mouse polyclonal) | gift from DJ Pan (Wu et al., 2003) | N/A |

| anti-Expanded (guinea pig polyclonal) | gift from R Fehon (Su et al., 2017) | NA |

| anti-Beta Gal (chicken polyclonal) | Abcam | Cat#:ab9361; RRID:AB_307210 |

| goat anti-mouse IgG IR Dye 700DX | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 926–32510; RRID:AB_1850021 |

| goat anti-rabbit IgG IR Dye 800CW | LI-COR Biosciences | Cat# 925–32211; RRID:AB_2651127) |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| ULK1 (1–649), active GST tagged, human | Sigma | Cat#:SRP5096 Lot: G1163–1 |

| human TAZ | OriGene Technologies | Cat#:TP304082 Lot: 1160CA |

| human Yap1 | OriGene Technologies | Cat#:TP325864 Lot: 10a73e |

| GST-Yki53–119-WT | This work | N/A |

| GST-Yki53–119-S74A | This work | N/A |

| GST-Yki53–119-S97A | This work | N/A |

| GST-Yki53–119-S74,97A | This work | N/A |

| DDNLQALFD-(p)S-VLNPGDAKR | This work; Genemed Synthesis | N/A |

| RMRKLPN-(p)S-FFTPPAPS | This work; Genemed Synthesis | N/A |

| H-XStable Prestained Protein Ladder | UBP-Bio | Cat#:L2021 |

| Fast SYBR Green Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat#:4385610 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase, Calf Intestinal | New England BioLabs | Cat#:M0290S |

| VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI | Vector Laboratories | Cat#:H-1200 |

| VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium | Vector Laboratories | Cat#:H-1000 |

| cOmplete™ ULTRA Tablets, Mini, EASYpack Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Roche | Cat#:5892970001 |

| Permount | Fisher | Cat#SP15–100 |

| [γ-32P]ATP | Perkin Elmer | Cat#NEG002A100UC |

| TransIT-2020 Transfection Reagent | Mirus | Cat#:MIR5404 |

| MagStrep “type3” XT beads | iba | Cat#:2-4090-002 |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#:20279 |

| Whatman 3MM Chr Chromatography paper | GE Healthcare | Cat#:05-716-3V |

| Paraformaldehyde for EM | Ted Pella Inc. | Cat#:18501 |

| Cacodylic Acid, Sodium Salt | Ted Pella Inc. | Cat#:18851 |

| Glutaraldehyde, 8% for EM | Ted Pella Inc. | Cat#:18422 |

| Hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat#:16700 |

| Amersham Protran Premium 0.45 μM Nitrocellulose Membrane | GE Healthcare | Cat#:10600003 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit | Applied Biosystems (now: Thermo Fisher Scientific) | Cat#:4368813 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Drosophila melanogaster S2 Cell Line | KCB | KCB Cat# KCB 200559YJ; RRID:CVCL_Z232 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Drosophila melanogaster, GMR-GAL4 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID: BDSC_1104 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, engrailed-GAL4, UAS-RFP/CyO | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID: BDSC_30557 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, engrailed-GAL4, UAS-m-Cherry/CyO | gift from DJ Pan | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Dcr-2; nubbin-GAL4 (Dcr-2 was removed before use) | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID: BDSC_25754 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, MS1096-GAL4 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID: BDSC_8860 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, Oregon-R | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_5 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[1118] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_3605 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, y[1] w[*]; P{w[+mC]=UAS-Atg1.S}6B | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_51655 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, y[1] w[*]; P{w[+mC]=UAS-yki.S168A.GFP.HA}10-12-1 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_28836 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[*]; P{y[+t7.7] w[+mC]=UAS-yki.S111A.S168A.S250A.V5}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_28817 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, P{ry[+t7.2]=hsFLP}1, w[1118]; Adv[1]/CyO | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_6 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, P{ry[+t7.2]=hsFLP}1, y[1] w[1118]; Dr[Mio]/TM3, ry[*] Sb[1] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_7 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[1118]; P{w[+mC]=GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S, P{w[+mC]=UAS-RFP.W}3/TM3, Sb[1] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_30558 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, P{ry[+t7.2]=hsFLP}1, w[1118]; P{w[+mC]=GAL4-Act5C(FRT.CD2).P}S, P{w[+mC]=UAS-GFP} | gift from DJ Pan; (Huang et al., 2005) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, P{ry[+t7.2]=hsFLP}12, y[1] w[*]; P{ry[+t7.2]=neoFRT}42D hpo[KS240]/CyO | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_25085 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[1118]; P{ry[+t7.2]=neoFRT}42D P{w[+mC]=Ubi-GFP(S65T)nls}2R/CyO | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_5626 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-ATG1 RNAi | Vienna Drosophila Resource Center | v16133; FBst0452169 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-ATG5 RNAi | Vienna Drosophila Resource Center | v104461; FBst0476319 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-ATG7 RNAi | Vienna Drosophila Resource Center | v45558; FBst0466207 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Acn RNAi | Vienna Drosophila Resource Center | v102407; FBst0474276 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Hpo RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_27661 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Acn RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_53676 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg1 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_26731 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg5 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_27551 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg5 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_34899 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg7 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_27707 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg7 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_34369 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg8 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_28989 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg8 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_34340 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg18 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_34714 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Atg18 RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_28061 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-AMPK RNAi | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_25931 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, Df(2L)al, ds[al]/In(2L)Cy, Duox[Cy] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_3548 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[1118]; Df(2R)ED3728, P{w[+mW.Scer\FRT.hs3]=3'.RS5+3.3'}ED3728/SM6a | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_9067 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[1118]; Df(3R)ED5664, P{w[+mW.Scer\FRT.hs3]=3'.RS5+3.3'}ED5664/TM6C, cu[1] Sb[1] | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_24137 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[1118]; Df(3R)ED6187, P{w[+mW.Scer\FRT.hs3]=3'.RS5+3.3'}ED6187/TM2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | RRID:BDSC_9347 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-Acn WT | (Nandi et al., 2017) | |

| Drosophila melanogaster, FRT42D ykiB5/CyO | (Huang et al., 2005) gift from DJ Pan | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, hsFlp; FRT40A LacZ | gift from DJ Pan | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, ubi-GFP acn[27] ubi-GFP FRT40A | (Haberman et al., 2010) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, hsFlp; r4-gal4 FRT82B UAS-GFPnls | gift from Andreas Jenny; (Mukherjee et al., 2016) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, FRT82B atg13(Δ81)/TM6B | gift from Andreas Jenny; (Mukherjee et al., 2016) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, y[1] w[*], hsFlp; ATG1(Δ3D) FRT80B/TM6B | gift from T Neufeld; (Scott et al., 2004) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, hsFlp; FRT80B, UAS-GFP | gift from DJ Pan | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, y[1] w[*]; sp/CyO; Bantam-LacZ/TM6B, Tb1 | gift from DJ Pan; (Herranz et al., 2012) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-myc-ATG1 | gift from T Neufeld; (Chang and Neufeld, 2009) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-myc-ATG1 (K38Q) | gift from T Neufeld; (Chang and Neufeld, 2009) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, UAS-ATG13-Flag | gift from T Neufeld; (Chang and Neufeld, 2009) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, M{UAS-Atg6.ORF.3xHA.GW}ZH-86Fb | FlyORF | F003089; FBst0502063 |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w; yki [S74A] | This work | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[*]; UAS-Yki.WT/CyO | gift from DJ Pan; (Huang et al., 2005) | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[*]; UAS-FLAG-Yki.S168A | This work | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[*]; UAS-FLAG-Yki.S74,168A | This work | N/A |

| Drosophila melanogaster, w[*]; UAS-FLAG-Yki.S74,97, 168A | This work | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| guide RNA1: GTCGGCTGCACCTGCGGAATGCC | Integrated DNA Technologies; This work | N/A |

| guide RNA2: GTCGGGAGTGATGTATCGCCAGG | Integrated DNA Technologies; This work | N/A |

| Forward PCR primers for Yki-S74AGATTACAACGACCACGACGA | Integrated DNA Technologies; This work | N/A |

| Reverse PCR primers for Yki-S74AATGGAGCTGGTGGTGTGAAG | Integrated DNA Technologies; This work | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pMT-TST-Myc-Sd | This work | N/A |

| pGEX-2T-Yki53–119_WT | This work | N/A |

| pGEX-2T-Yki53–119_S74A | This work | N/A |

| pGEX-2T-Yki53–119_S97A | This work | N/A |

| pGEX-2T-Yki53–119_S74,97A | This work | N/A |

| pAttB-UAS-FLAG-Yki.S168A | This work | N/A |

| pAttB-UAS-FLAG-Yki.S74,168A | This work | N/A |

| pAttB-UAS-FLAG-Yki.S74,97,168A | This work | N/A |

| pCDF3-dU6-Yki-gRNA1 | This work | N/A |

| pCDF3-dU6-Yki-gRNA2 | This work | N/A |

| pCDF3-dU6 | (Port et al., 2014) | Addgene; Cat#: 49410 |

| pBS-Flag-Yki-S74A_HDR | This work | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Imaris software | Bitplane | RRID:SCR_007370 |

| Adobe Photoshop | Adobe | RRID:SCR_014199 |

| ImageJ | NIH | RRID:SCR_003070 |

| Image Studio ver 5.2 | LI-COR | RRID:SCR_015795 |

| Prism | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 |

Highlights.

Atg1 phosphorylates Yorkie at two ULK1/Atg1 consensus target sites

Atg1-mediated phosphorylation blocks Scalloped binding and inhibits Yorkie activity

This phosphorylation does not interfere with Yorkie’s nuclear localization

Yorkie phosphorylation by Atg1 is promoted by elevated Acinus levels

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Dean Smith. Jon Terman and Duojia Pan for helpful comments to the manuscript and members of the Krämer lab for discussion and technical assistance. We thank Drs. Ken Irvine, Thomas Neufeld, Jin Jiang, Duojia Pan, the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) for flies, Drs. Duojia Pan, Iswar Hariharan, Dean Smith and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at The University of Iowa for antibodies and the Molecular and Cellular Imaging Facility at UT Southwestern Medical Center (NIH S10 OD020103-01) for help with electron microscopy. This work was funded by NIH grants EY010199, GM120196 to H.K. and NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (4900835401-36068) to L.K.T.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abrams JM (1999). An emerging blueprint for apoptosis in Drosophila. Trends in cell biology 9, 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar MA, Tracy C, Kahr WH, and Krämer H (2011). The full-of-bacteria gene is required for phagosome maturation during immune defense in Drosophila. The Journal of cell biology 192, 383–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alers S, Wesselborg S, and Stork B (2014). ATG13: just a companion, or an executor of the autophagic program? Autophagy 10, 944–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YY, and Neufeld TP (2009). An Atg1/Atg13 complex with multiple roles in TOR-mediated autophagy regulation. Mol Biol Cell 20, 2004–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chan SW, Zhang X, Walsh M, Lim CJ, Hong W, and Song H (2010). Structural basis of YAP recognition by TEAD4 in the hippo pathway. Genes & development 24, 290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codelia VA, Sun G, and Irvine KD (2014). Regulation of YAP by mechanical strain through Jnk and Hippo signaling. Current biology: CB 24, 2012–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, and Pan D (2007). Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 130, 1120–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Chun MG, Vamos M, Zou H, Rong J, Miller CJ, Lou HJ, Raveendra-Panickar D, Yang CC, Sheffler DJ, et al. (2015). Small Molecule Inhibition of the Autophagy Kinase ULK1 and Identification of ULK1 Substrates. Mol Cell 59, 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R, et al. (2011). Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science 331, 456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailite I, Aerne BL, and Tapon N (2015). Differential control of Yorkie activity by LKB1/AMPK and the Hippo/Warts cascade in the central nervous system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, E5169–5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genevet A, Wehr MC, Brain R, Thompson BJ, and Tapon N (2010). Kibra is a regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling network. Developmental cell 18, 300–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberman AS, Akbar MA, Ray S, and Krämer H (2010). Drosophila acinus encodes a novel regulator of endocytic and autophagic trafficking. Development 137, 2157–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Dupont S, and Piccolo S (2012). Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 13, 591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C, Jafar-Nejad H, and Halder G (2006). The tumour-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signalling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nature cell biology 8, 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan IK (2015). Organ Size Control: Lessons from Drosophila. Developmental cell 34, 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, and Hariharan IK (2003). The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell 114, 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi R, Handler D, Ish-Horowicz D, and Brennecke J (2014). The exon junction complex is required for definition and excision of neighboring introns in Drosophila. Genes & development 28, 1772–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herranz H, Hong X, and Cohen SM (2012). Mutual repression by bantam miRNA and Capicua links the EGFR/MAPK and Hippo pathways in growth control. Current biology: CB 22, 651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, and Pan D (2005). The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell 122, 421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Zhang W, Wang B, Trinko R, and Jiang J (2003). The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes & development 17, 2514–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, and Halder G (2014). The two faces of Hippo: targeting the Hippo pathway for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. Nature reviews Drug discovery 13, 63–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo JH, Wang B, Frankel E, Ge L, Xu L, Iyengar R, Li-Harms X, Wright C, Shaw TI, Lindsten T, et al. (2016). The Noncanonical Role of ULK/ATG1 in ER-to-Golgi Trafficking Is Essential for Cellular Homeostasis. Mol Cell 62, 491–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukam D, Xie B, Rister J, Terrell D, Charlton-Perkins M, Pistillo D, Gebelein B, Desplan C, and Cook T (2013). Opposite feedbacks in the Hippo pathway for growth control and neural fate. Science 342, 1238016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, Kundu M, and Kim DH (2009). ULK-Atg13-FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell 20, 1992–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaan HYK, Chan SW, Tan SKJ, Guo F, Lim CJ, Hong W, and Song H (2017). Crystal structure of TAZ-TEAD complex reveals a distinct interaction mode from that of YAP-TEAD complex. Sci Rep 7, 2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karra AS, Stippec S, and Cobb MH (2017). Assaying Protein Kinase Activity with Radiolabeled ATP. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, and Guan KL (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nature cell biology 13, 132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Liu R, Dong X, and Zhong Q (2015). Beclin orthologs: integrative hubs of cell signaling, membrane trafficking, and physiology. Trends in cell biology 25, 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhao B, Wang P, Chen F, Dong Z, Yang H, Guan KL, and Xu Y (2010). Structural insights into the YAP and TEAD complex. Genes & development 24, 235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MG, and Hurley JH (2016). Structure and function of the ULK1 complex in autophagy. Current opinion in cell biology 39, 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CD, Mestdagh C, Akhtar J, Kreim N, Deinhard P, Sachidanandam R, Treisman J, and Roignant JY (2014). The exon junction complex controls transposable element activity by ensuring faithful splicing of the piwi transcript. Genes & development 28, 1786–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura M (2012). Apoptotic and nonapoptotic caspase functions in animal development. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N (2010). The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Current opinion in cell biology 22, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo JS, Meng Z, Kim YC, Park HW, Hansen CG, Kim S, Lim DS, and Guan KL (2015). Cellular energy stress induces AMPK-mediated regulation of YAP and the Hippo pathway. Nature cell biology 17, 500–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Patel B, Koga H, Cuervo AM, and Jenny A (2016). Selective endosomal microautophagy is starvation-inducible in Drosophila. Autophagy 12, 1984–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murachelli AG, Ebert J, Basquin C, Le Hir H, and Conti E (2012). The structure of the ASAP core complex reveals the existence of a Pinin-containing PSAP complex. Nature structural & molecular biology 19, 378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi N, and Kramer H (2018a). Cdk5-mediated Acn/Acinus phosphorylation regulates basal autophagy independently of metabolic stress. Autophagy in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi N, and Kramer H (2018b). Cdk5-mediated Acn/Acinus phosphorylation regulates basal autophagy independently of metabolic stress. Autophagy 14, 1271–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi N, Tyra LK, Stenesen D, and Kramer H (2017). Stress-induced Cdk5 activity enhances cytoprotective basal autophagy in Drosophila melanogaster by phosphorylating acinus at serine(437). eLife 6, pii: e30760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi N, Tyra LK, Stenesen D, and Krämer H (2014). Acinus integrates AKT1 and subapoptotic caspase activities to regulate basal autophagy. The Journal of cell biology 207, 253–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy A, Lin L, Velentzas PD, Wu LP, Baehrecke EH, and Silverman N (2018). The NF-kappaB Factor Relish Regulates Atg1 Expression and Controls Autophagy. Cell reports 25, 2110–2120.e2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HB, Babcock JT, Wells CD, and Quilliam LA (2013). LKB1 tumor suppressor regulates AMP kinase/mTOR-independent cell growth and proliferation via the phosphorylation of Yap. Oncogene 32, 4100–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolo R, Morrison CM, Tao C, Zhang X, and Halder G (2006). The bantam microRNA is a target of the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway. Current biology: CB 16, 1895–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K, Wicky C, Magnenat L, Tobler H, Mori I, Muller F, and Ohshima Y (1994). Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes & development 8, 2389–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, and Irvine KD (2008). In vivo regulation of Yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development 135, 1081–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, and Irvine KD (2009). In vivo analysis of Yorkie phosphorylation sites. Oncogene 28, 1916–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papinski D, Schuschnig M, Reiter W, Wilhelm L, Barnes CA, Maiolica A, Hansmann I, Pfaffenwimmer T, Kijanska M, Stoffel I, et al. (2014). Early steps in autophagy depend on direct phosphorylation of Atg9 by the Atg1 kinase. Mol Cell 53, 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Jung CH, Seo M, Otto NM, Grunwald D, Kim KH, Moriarity B, Kim YM, Starker C, Nho RS, et al. (2016). The ULK1 complex mediates MTORC1 signaling to the autophagy initiation machinery via binding and phosphorylating ATG14. Autophagy 12, 547–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J, and Struhl G (2015). Scaling the Drosophila Wing: TOR-Dependent Target Gene Access by the Hippo Pathway Transducer Yorkie. PLoS Biol 13, e1002274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe SW, Hong AW, and Guan KL (2015). Disease implications of the Hippo/YAP pathway. Trends in molecular medicine 21, 212–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C, Pan G, Reddy BV, Oh H, and Irvine KD (2011). Zyxin links fat signaling to the hippo pathway. PLoS Biol 9, e1000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren F, Zhang L, and Jiang J (2010). Hippo signaling regulates Yorkie nuclear localization and activity through 14-3-3 dependent and independent mechanisms. Developmental biology 337, 303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodor J, Pan Q, Blencowe BJ, Eyras E, and Caceres JF (2016). The RNA-binding profile of Acinus, a peripheral component of the exon junction complex, reveals its role in splicing regulation. Rna 22, 1411–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, Park HW, Chang YY, Kim J, Kim H, Neufeld TP, Dillin A, and Guan KL (2013). ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nature cell biology 15, 741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, and Steller H (2002). Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nature cell biology 4, 432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santinon G, Pocaterra A, and Dupont S (2016). Control of YAP/TAZ Activity by Metabolic and Nutrient-Sensing Pathways. Trends in cell biology 26, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerk C, Prasad J, Degenhardt K, Erdjument-Bromage H, White E, Tempst P, Kidd VJ, Manley JL, Lahti JM, and Reinberg D (2003). ASAP, a novel protein complex involved in RNA processing and apoptosis. Molecular and cellular biology 23, 2981–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RC, Juhasz G, and Neufeld TP (2007). Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Current biology: CB 17, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang L, Chen S, Du F, Li S, Zhao L, and Wang X (2011). Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 4788–4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda N, Hanawa N, Chihara T, Koto A, and Miura M (2019). Dronc-independent basal executioner caspase activity sustains Drosophila imaginal tissue growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116, 20539–20544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenesen D, Moehlman AT, and Kramer H (2015). The carcinine transporter CarT is required in Drosophila photoreceptor neurons to sustain histamine recycling. eLife 4, e10972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T, Ludwig MZ, Xu J, and Fehon RG (2017). Kibra and Merlin Activate the Hippo Pathway Spatially Distinct from and Independent of Expanded. Developmental cell 40, 478–490.e473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BJ, and Cohen SM (2006). The Hippo pathway regulates the bantam microRNA to control cell proliferation and apoptosis in Drosophila. Cell 126, 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian W, Yu J, Tomchick DR, Pan D, and Luo X (2010). Structural and functional analysis of the YAP-binding domain of human TEAD2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, 7293–7298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda H, Mochizuki H, Flores R 3rd, Josowitz R, Krasieva TB, Lamorte VJ, Suzuki E, Gindhart JG, Furukubo-Tokunaga K, and Tomoda T (2008). UNC-51/ATG1 kinase regulates axonal transport by mediating motor-cargo assembly. Genes & development 22, 3292–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoda T, Kim JH, Zhan C, and Hatten ME (2004). Role of Unc51.1 and its binding partners in CNS axon outgrowth. Genes & development 18, 541–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udan RS, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, and Halder G (2003). Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nature cell biology 5, 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Iyengar R, Li-Harms X, Joo JH, Wright C, Lavado A, Horner L, Yang M, Guan JL, Frase S, et al. (2017). The autophagy-inducing kinases, ULK1 and ULK2, regulate axon guidance in the developing mouse forebrain via a noncanonical pathway. Autophagy, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, and Kundu M (2017). Canonical and noncanonical functions of ULK/Atg1. Current opinion in cell biology 45, 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehr MC, Holder MV, Gailite I, Saunders RE, Maile TM, Ciirdaeva E, Instrell R, Jiang M, Howell M, Rossner MJ, et al. (2013). Salt-inducible kinases regulate growth through the Hippo signalling pathway in Drosophila. Nature cell biology 15, 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wold MS, Lim J, Lachance V, Deng Z, and Yue Z (2016). ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of ATG14 promotes autophagy and is impaired in Huntington’s disease models. Molecular neurodegeneration 11, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff T (2011). Preparation of Drosophila eye specimens for scanning electron microscopy. Cold Spring Harbor protocols 2011, 1383–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PM, Puente C, Ganley IG, and Jiang X (2013). The ULK1 complex: sensing nutrient signals for autophagy activation. Autophagy 9, 124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Huang J, Dong J, and Pan D (2003). hippo encodes a Ste-20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with salvador and warts. Cell 114, 445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, and Pan D (2008). The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Developmental cell 14, 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachari M, and Ganley IG (2017). The mammalian ULK1 complex and autophagy initiation. Essays in biochemistry 61, 585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, and Jiang J (2008). The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Developmental cell 14, 377–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, Kim J, Xie J, Ikenoue T, Yu J, Li L, et al. (2007). Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes & development 21, 2747–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, Yu J, Lin JD, Wang CY, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. (2008). TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes & development 22, 1962–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, and Klionsky DJ (2011). AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of ULK1 induces autophagy. Cell Metab 13, 119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, and Pan D (2019). The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Developmental cell 50, 264–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate data sets or code.