Abstract

Expansions of simple tandem repeats are responsible for almost 50 human diseases, the majority of which are severe, degenerative, and not currently treatable or preventable. In this review, we first describe the molecular mechanisms of repeat-induced toxicity, which is the connecting link between repeat expansions and pathology. We then survey alternative DNA structures that are formed by expandable repeats and review the evidence that formation of these structures is at the core of repeat instability. Next, we describe the consequences of the presence of long structure-forming repeats at the molecular level: somatic and intergenerational instability, fragility, and repeat-induced mutagenesis. We discuss the reasons for gender bias in intergenerational repeat instability and the tissue specificity of somatic repeat instability. We also review the known pathways in which DNA replication, transcription, DNA repair, and chromatin state interact and thereby promote repeat instability. We then discuss possible reasons for the persistence of disease-causing DNA repeats in the genome. We describe evidence suggesting that these repeats are a payoff for the advantages of having abundant simple-sequence repeats for eukaryotic genome function and evolvability. Finally, we discuss two unresolved fundamental questions: (i) why does repeat behavior differ between model systems and human pedigrees, and (ii) can we use current knowledge on repeat instability mechanisms to cure repeat expansion diseases?

Keywords: trinucleotide repeat disease, DNA replication, DNA repair, DNA recombination, genomic instability, gene expression, DNA structure, G-quadruplex, R-loop, S-DNA, triplex H-DNA, Huntington disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Lou Gehrig disease), hairpin

Introduction

In 1905, British ophthalmologist Edward Nettleship made a peculiar observation: children that suffered from certain degenerative genetic diseases exhibited pathological symptoms earlier than their parents. Nettleship termed this phenomenon “genetic anticipation” (1). This concept was further substantiated by Bruno Fleischer in his genetic studies of myotonic dystrophy (DM)2 with cataracts (2).

For most of the 20th century, the idea of genetic anticipation was highly controversial due to its adoption, misinterpretation, and abuse by eugenicists. Most notably, Nazi officials used the concept to justify the sterilization of people who exhibited mild symptoms of mental disorders, believing that these symptoms were harbingers of severe psychopathology in later generations (3).

The post-war political backlash against eugenics spelled the near demise for genetic anticipation as a serious scientific concept. The scientific community firmly rejected the existence of non-Mendelian inheritance of this type. Nonetheless, a growing body of evidence began to show that patterns of inheritance in certain types of human diseases, such as DM or Huntington's disease (HD) are hard to explain using conventional genetics (3). Furthermore, in 1985, Stephany Sherman convincingly demonstrated that penetrance and expressivity of fragile X syndrome alleles increase as the disease alleles pass through generations. This phenomenon became known as the Sherman paradox (4).

In 1991, two disease-causing genes were cloned: the fragile X gene FMR1 in the laboratories of Stephen Warren, Robert Richards, and Jean-Louis Mandel (5–9) and the X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA) gene AR in the laboratory of Kenneth Fischbeck (10). These feats revealed the molecular basis of the genetic anticipation. It turned out that fragile X syndrome results from an expansion of the CGG repeats in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of the FMR1 gene (5–9). The number of CGG repeats expands during parental transmission, leading to increased disease severity. These observations resolved Sherman's paradox and provided a molecular explanation for genetic anticipation. Similarly to fragile X, SBMA was found to be caused by an expansion of CAG repeats in the coding region of the AR gene (10). These discoveries were rapidly followed by the recognition of repeat expansion as the cause of DM1 (11) and HD (12). In the blink of an eye, the infamous concept of genetic anticipation was reestablished as a valid scientific phenomenon (3).

Today, we know 13 different types of tandem repeats whose expansions cause various human diseases (Table 1). The majority of these repeat expansion diseases (REDs) are neither curable nor preventable at present. The most common cause of REDs is an expansion of CAG repeats (or complementary CTG repeats), which are responsible for 16 conditions, including HD and multiple spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs). CGG repeat expansions cause six different conditions, including fragile X syndrome. Next, two disorders are caused by GAA repeat expansion. In addition to the expansions of these trinucleotide repeats, expansions of one tetranucleotide (CCTG), five pentanucleotide (ATTCT, TGGAA, TTTTA, TTTCA, and AAGGG), three hexanucleotide (GGCCTG, CCCTCT, and GGGGCC), and one dodecanucleotide (CCCCGCCCCGCG) repeat cause 13 other diseases. A separate class of REDs, so-called polyalanine (poly(A)) diseases, are caused by an in-frame expansion of imperfect GCN repeats. This expansion results in abnormally long stretches of alanine in the corresponding proteins. Altogether, nearly 50 REDs are currently known. Beyond these monogenic diseases, some specific repeat expansions might contribute to the etiology of various complex polygenic psychiatric and brain disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (13), bipolar spectrum disorders, schizophrenia, and others (reviewed in Ref. 14). The number of known REDs will likely grow, as more than 100 human genes contain DNA repeats that are known to expand in some REDs. These repeats, therefore, can a priori expand, causing a disease (database of genes related to REDs RRID:SCR_018086).

Table 1.

Currently known REDs

| Repeat unit | Gene and position of the repeat in the gene | Disease | Year of discovery | Highlight paper | Inheritance pattern | Healthy range, no. of repeats | Symptomatic range, no. of repeats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTCT | ATXN10, intron | Spinocerebellar ataxia 10 (SCA10) | 2000 | 535 | Autosomal dominant | 10–22 | 500–4500 |

| DAB1; intron | Spinocerebellar ataxia 37 (SCA37) | 2017 | 22 | Autosomal dominant | <30 | 46–71 | |

| CAG | ATXN1, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia1 (SCA1) | 1993 | 536 | Autosomal dominant | 6–39 | 41–83 |

| ATXN2, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia2 (SCA2) | 1996 | 21, 537 | Autosomal dominant | <31 | 33–200 | |

| ATXN3, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia3 (SCA3) | 1994 | 18 | Autosomal dominant | <44 | 52–86 | |

| CACNA1A, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia6 (SCA6) | 1997 | 538 | Autosomal dominant | <18 | 20–33 | |

| TPB, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia 17 (SCA17) | 2001 | 539 | Autosomal dominant | 25–44 | 47–63 | |

| ATN1, coding sequence | Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy, Naito-Oyanagi disease (DRPLA) | 1994 | 29, 30 | Autosomal dominant | 6–35 | 49–88 | |

| HTT, coding sequence | Huntington disease (HD) | 1993 | 12 | Autosomal dominant | 9–29 | 36–121 | |

| ATXN8, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia8 (SCA8) | 1999 | 114 | Autosomal dominant | 15–50 | 71–1300 | |

| PPP2R2B, 5′ UTR | Spinocerebellar ataxia 12 (SCA12) | 1999 | 540 | Autosomal dominant | 7–32 | 51–78 | |

| ATXN7, coding sequence | Spinocerebellar ataxia7 (SCA7) | 1997 | 17 | Autosomal dominant | 7–17 | 38–130 | |

| AR, coding sequence | Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA) | 1991 | 10 | X-linked recessive | <34 | >38 | |

| GLS, 5′-UTR | Glutaminase deficiency (GD) | 2019 | 470 | Autosomal recessive | 8–16 | 400–1500 | |

| CCCCGCCCCGCG | CSTB, 5′-UTR | Progressive myoclonus epilepsy of the Unverricht--Lundborg type (EPM1) | 1997 | 541 | Autosomal recessive | 2–3 | 38–77 |

| CCCTCT | TAF1, intron | X-linked dystonia parkinsonism (XDP) | 2019 | 31 | X-linked recessive | N/A | 30–60 |

| CCTG | CNBP, intron | Myotonic mystrophy2 (DM2) | 2001 | 54 | Autosomal dominant | <30 | 75–11,000 |

| CTG | DM1, 3′-UTR | Myotonic mystrophy1 (DM1) | 1992 | 11 | Autosomal dominant | 5–37 | 50–5,000 |

| JPH3, 3′-UTR | Huntington disease-like 2 | 2001 | 542 | Autosomal dominant | 6–28 | >41 | |

| ATXN8, intron | Spinocerebellar ataxia8 (SCA8) | 1999 | 114 | Autosomal dominant | 15–34 | 90–250 | |

| TCF4, intron | Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy | 2012 | 543 | Autosomal dominant | <40 | >50 | |

| GAA | DMD, intron | Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | 2016 | 64 | X-linked recessive | 11–33 | 59–82 |

| FXN, intron | Friedreich ataxia 1 (FRDA) | 1996 | 62 | Autosomal recessive | 5–30 | >70 | |

| CGG | XYLT1, 5′-UTR | Baratela--Scott syndrome (BSS) | 2019 | 544 | Autosomal recessive | 9–20 | 100–800 |

| FMR2, 5′-UTR | Mental retardation, X-linked, associated with fragile site FRAXE | 1993 | 545 | X-linked recessive | 4–39 | >200 | |

| DIP2B, 5′-UTR | Mental retardation, associated with fragile site FRA12A | 2007 | 546 | Autosomal dominant | 12–26 | >150 | |

| FMR1, 5′-UTR | Fragile X mental retardation syndrome | 1991 | 5–9 | X-linked dominant | 6–52 | 231–2000 | |

| CBL, 5′-UTR | Jacobsen syndrome | 1998 | 547 | Not inherited | 11 | >100 | |

| NOTCH2NLC | Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (NIID) | 2019 | 380 | Autosomal dominant | 13–30 | 60–959 | |

| GCN (polyAla) | RUNX2, coding sequence | Cleidocranial dysplasia | 1997 | 42 | Autosomal dominant | 17 | 27 |

| SOX3, coding sequence | Mental retardation, X-linked | 2002 | 43 | X-linked recessive | 11 | 15–26 | |

| PRDM12, coding sequence | Congenital insensitivity to pain (CIP) | 2015 | 44 | Autosomal recessive | 12 | 18–19 | |

| PABPN1, coding sequence | Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy | 1998 | 45 | Autosomal dominant | 6 | 7–17 | |

| HOXD13, coding sequence | Synpolydactyly 1 | 1996 | 46, 47 | Autosomal dominant | 15 | 22–29 | |

| HOXA13, coding sequence | Hand-foot-genital (HFG) syndrome | 2000 | 48 | Autosomal dominant | 18 | 24–26 | |

| ARX, coding sequence | Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 1 | 2007 | 49, 50 | X-linked recessive | 10–16 | 17–23 | |

| PHOX2B, coding sequence | Central hypoventilation syndrome, congenital | 2003 | 51 | Autosomal dominant | 20 | 24–33 | |

| ZIC2, coding sequence | Holoprosencephaly 5 | 2001 | 52 | Autosomal dominant | 15 | 25 | |

| FOXL2, coding sequence | Blepharophimosis, ptosis, and epicanthus inversus syndrome | 2001 | 53 | Autosomal dominant | 14 | 22–24 | |

| GGCCTG | NOP56, intron | Spinocerebellar ataxia 36 (SCA36) | 2011 | 93 | Autosomal dominant | 3–14 | 650–2500 |

| GGGGCC | C9orf72, intron | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal degeneration (ALS/FTD) | 2011 | 37, 100 | Autosomal dominant | 2–19 | 250–1600 |

| TGGAA | BEAN1, intron | Spinocerebellar ataxia 31 (SCA31) | 2009 | 548 | Autosomal dominant | 26 | 500–760 |

| TTTCA/TTTTA | SAMD12, intron | Familial adult myoclonic epilepsy1 (FAME1) | 2018 | 67, 68 | Autosomal dominant | 7–20 | 440–3680 |

| TNRC6A, intron | Familial adult myoclonic epilepsy6 (FAME6) | 2018 | 67, 68 | Autosomal dominant | 18 | >22 | |

| RAPGEF2, intron | Familial adult myoclonic epilepsy7 (FAME7) | 2018 | 67, 68 | Autosomal dominant | 18 | >22 | |

| MARCH6, intron | Familial adult myoclonic epilepsy3 (FAME3) | 2019 | 32 | Autosomal dominant | 9–20 | 791–1035 | |

| STARD7, intron | Familial adult myoclonic epilepsy2 (FAME2) | 2019 | 69 | Autosomal dominant | 5–35 | 40–1000 | |

| AAGGG | RFC1, intron | Cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome | 2019 | 291 | Autosomal recessive | 11 | 400–2000 |

The majority of REDs share two common features. First, the number of inherited repeats typically positively correlates with disease severity and negatively correlates with age of onset. Diseases with strong correlations between the number of repeats and age of onset are SCA7 (16, 17), SCA3 (18), SCA2 (19–21), SCA37 (22), HD (23–26), DM1 (27, 28), dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA) (29, 30), X-linked dystonia parkinsonism (XDP) (31), familial adult myoclonic epilepsy 3 (FAME3) (32), and Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) (33, 34). For some disorders, the correlation between the number of repeats and symptom manifestation is less clear, although there typically is a marginally significant trend (35–39). Second, expansion of one disease-causing repeat does not promote expansions of other repeats in the patient's genome. In other words, each RED patient typically has only a single repeat type expanded (40, 41).

Other characteristics differ among REDs. First, even though repeat expansion is necessary for some RED manifestation, there are REDs in which mutations other than repeat expansions can cause the same disease. Second, the RED mode of inheritance can be either autosomal recessive, dominant, or X-linked. Third, REDs can demonstrate a clear pattern of genetic anticipation (11, 23) or a complete lack thereof (34). Fourth, expandable repeats can be located in the coding part of a gene, in an intron, or in the 5′- or 3′-UTR. Fifth, the size of repeat expansion sufficient to cause pathological symptoms ranges from several repeat units for poly(A) diseases (42–53) to thousands for DM1 (11) and DM2 (54). Sixth, the origin of expanded alleles varies across repeats. For example, single common ancestors had a pathogenic amplification of ATTCT repeats in SCA10 (55–57), CCTG repeats in DM2 (58), and TTTTA/TTTCA repeats in FAME3 (32). Contrastingly, de novo repeat expansions were reported for the CAG repeat in HD (59), the CGG repeat in fragile X syndrome (60), and the GCN repeat in hand-foot-genital (HFG) syndrome (61). Last, the mechanisms of repeat toxicity vary among different repeats and include both a loss and gain of function.

The goal of this review is to depict the molecular mechanisms implicated in REDs. We first describe models of repeat-induced pathogenicity. We then discuss how repeat length instability and the propensity to induce various types of mutations compromises genome integrity. The focal point of the review is the description of the molecular mechanisms responsible for repeat instability and repeat-induced mutagenesis (RIM). Whereas these mechanisms were primarily established in model experimental systems, we discuss their relevance to human REDs whenever it is possible. Then we reflect on the existence of expandable repeats from the standpoints of genome function and evolvability. As for future directions, we discuss possible reasons for the differences in expandable repeats' behavior in model systems versus human pedigrees as well as how we could use our current knowledge about characteristics and instability of expandable repeats to develop therapies for REDs.

From expanded DNA repeats to disease

Repeat expansions induce changes in cell metabolism that become detrimental to the function of specific tissues. What are these changes? First, an expanded repeat located within a gene may lead to a transcription defect and consequently a loss of function of the carrier gene. Such a loss-of-function mechanism predicts an autosomal recessive or X-linked mode of inheritance. It also predicts that in a subset of patients, an inactivation of the same gene could happen due to a missense, indel, or frameshift mutation, instead of repeat expansion. Both of these predictions are true for autosomal recessive FRDA (62), progressive myoclonus epilepsy of the Unverricht–Lundborg type (EPM1) (63), Congenital insensitivity to pain (44), X-linked Duchenne muscular dystrophy (64), and fragile X syndrome (65, 66).

The majority of REDs exhibit an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance and are caused exclusively by repeat expansions. Moreover, an expansion of a particular repeat may have the same detrimental consequences regardless of the gene in which this expansion happens. For example, expansion of (CAG)n repeats in 13 different genes causes SCAs. Similarly, recently discovered expansions of (TTTTA)n(TTTCA)m repeats in the introns of five different genes are all linked to FAME (32, 67–69). Therefore, researchers have proposed toxic gain-of-function mechanisms, which could be either at the RNA or protein levels.

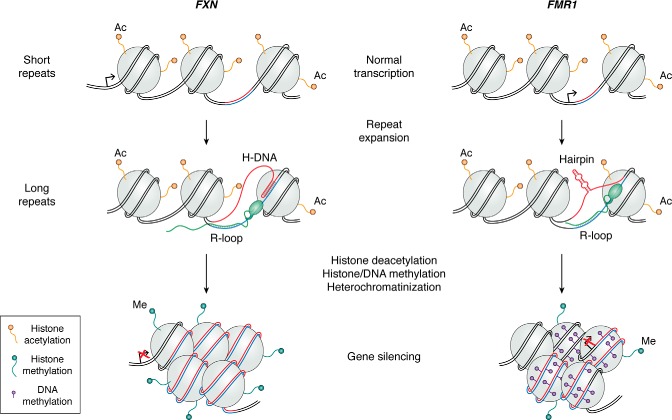

Loss of function of a gene with an expanded repeat tract

Long repeat tracts can impede transcription of their corresponding gene (70) and therefore lead to decreased production of an essential protein (31, 62, 71). This process could occur in several ways. Formation of RNA-DNA hybrids (R-loops) potentially combined with formation of an unusual secondary structure within the expanded repeats may physically stall transcription (72). For example, in FRDA, RNA polymerase fails to successfully transcribe through expanded GAA repeats located in the intron of the FXN gene (62, 71), likely because of the formation of R-loop–containing structures (73, 74), such as an H-loop (75). This transcription hindrance leads to the appearance of repressive chromatin marks at and around an expanded repeat, ultimately leading to local heterochromatinization and gene repression (reviewed in Ref. 76) (Fig. 1). Reduced FXN expression causes mitochondrial dysfunction, which eventually leads to cell death (77, 78). Similarly, R-loop formation within expanded CGG (72, 79) repeats in the 5′-UTR of the FMR1 gene leads to promoter DNA methylation at the repeat and the adjacent promoter (80), followed by histone and DNA methylation, resulting in massive heterochromatinization that can spread up to 1.8 Mb (reviewed in Ref. 81) (Fig. 1). It is, in fact, this constitutive heterochromatinization that slows down DNA replication through this region, leading to the characteristic fragile X phenotype (82).

Figure 1.

Loss-of-function mechanisms caused by expanded repeats exemplified by GAA repeats in FXN and CGG repeats in FMR1 genes. Repeats are shown in blue and red, and the flanking DNA sequences are shown in black. Top, when repeats are short, transcription is unimpeded. Bottom left, expansion of GAA repeats leads to formation of an R-loop at the repeat, which triggers histone deacetylation and the presence of repressive histone marks (such as histone H3 Lys-9 methylation), heterochromatization, and gene silencing (reviewed in Ref. 76). Bottom right, expansion of CGG repeats leads to formation of an R-loop at the repeat, which triggers methylation of the repeat as well as of the CpG islands upstream of the FMR1 promoter, followed by histone methylation. This results in heterochromatization and, ultimately, gene silencing (reviewed in Ref. 81).

Expansion of the dodecamer CCCCGCCCCGCG repeat in the 5′-UTR of the CSTB gene seems to decrease CSTB gene expression by a mechanism different from that discussed above. This repeat is located between two cis-regulatory elements that activate CSTB transcription. Expansion of the repeat increases the distance between the two regulatory elements such that it prevents efficient transcription initiation of the CSTB gene (63).

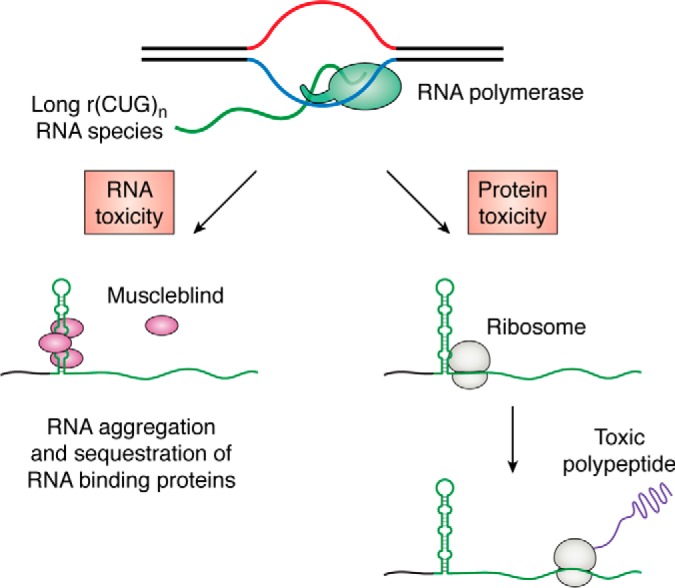

Toxic gain of function at the level of RNA

Growing evidence suggests that some expanded repeats exhibit cellular toxicity on their own, rather than in a context of their carrier gene. One example is the expansion of CCTG repeats in an intron of the CNBP gene (in DM2). This expansion does not directly affect gene expression: it changes neither the methylation pattern of the gene promoter (83) nor the splicing pattern of CNBP mRNA nor the CNBP protein level (84). Instead, expanded CCTG repeats are transcribed into toxic repetitive RNA. The toxicity of expanded RNA repeats is likely associated with their ability to fold into unusual RNA secondary structures. The list of known repetitive RNAs with confirmed toxicity includes CUG, CCUG, CGG, CAG, AUUCU, UGGAA, AUUUC, GGCCUG, and GGGGCC repeats (22, 85–94).

What are the molecular mechanisms of this toxicity? Expanded repetitive RNAs can engage in multivalent base pairing, which leads to their gelation and aggregation into visible nuclear foci (95). As a consequence, these RNAs remain in the nucleus and might sequester RNA-binding proteins. In the best-studied cases of DM1 and DM2 diseases, expanded RNA repeats sequester Muscleblind (Mbnl) proteins, whose normal function is to regulate splicing of muscle-specific genes (96) (Fig. 2). This mechanism is evidenced by the fact that disruption of the MBNL1 gene leads to the same symptoms as the expression of expanded repeats alone (97). For other repeats, the precise toxicity mechanism is less understood. Expression of r(GGGGCC)exp causes length-dependent cognitive impairment in mice (98), but the mechanistic connection between RNA expression and symptoms remains unclear. This repetitive RNA folds into G-quadruplexes (99), forms nuclear foci (98, 100), sequesters important RNA-binding proteins (101–104), and impairs mRNA transport (105) likely by damaging the nuclear pore complex (106). However, it is not yet clear which of these features of the r(GGGGCC)exp repeats is primarily responsible for toxicity.

Figure 2.

Toxic gain-of-function mechanisms in REDs exemplified by an expansion of a CTG repeat. Left, transcription of expanded CTG repeats produces long r(CUG)n RNA species that fold into RNA secondary structures, aggregate, and sequester the Muscleblind protein. This is the main source of toxicity in DM1 disease (reviewed in Ref. 15). Right, RAN translation of r(CUG)n. Expanded RNA repeats recruit ribosomes. This recruitment is likely mediated by the formation of an RNA secondary structure. Translation of r(CUG)n results in accumulation of toxic repetitive polypeptides in all three reading frames (reviewed in Refs. 123–125). Note that antisense transcription of the same repeat might also undergo RAN translation (not shown).

Toxic gain of function at the level of protein

A group of REDs are caused by expansions of GCN or CAG repeats located in coding parts of various genes. Translation of these in-frame repeats results in abnormally long poly(A) or polyglutamine poly(Q) tracts in their corresponding proteins. These long tracts could abrogate function of a protein and/or exhibit toxic gain of function.

Poly(A) tracts are common protein motifs that were suggested to promote protein interactions (107) or serve as nuclear export signals (108). At the molecular level, poly(A) peptides undergo a conformational change as their length increases. Whereas short poly(A) tracts preferably form monomeric α-helices, longer tracts fold into polymeric β-sheets (reviewed in Ref. 109) and into coiled coils (110). These conformational changes can lead to a toxic gain of function by introducing novel types of protein interactions, aggregation, mislocalization, and sequestration of other essential proteins. Commonly, proteins with poly(A) expansions co-aggregate with their WT versions, leading to effective haploinsufficiency, which explains their dominant inheritance patterns (reviewed in Ref. 109).

Similar to expanded poly(A) tracts, long poly(Q) tracts misfold into β-sheet structures that aggregate into toxic inclusion bodies in neurons. These structures might act as so-called “polar zippers,” which exhibit nonspecific affinity to various regulatory proteins in a cell (111). Accumulation of poly(Q) runs is believed to cause neurodegeneration (reviewed in Ref. 112). First discovered in 1997 for CAG repeats in HD (113), poly(Q) accumulation was used to explain symptoms of SCAs and other diseases caused by expansions of translated CAG repeats. However, there was one mysterious exception: SCA8. Unlike other SCAs, SCA8 is caused by an expansion of transcribed CTG rather than CAG repeats. Nonetheless, its symptoms resemble other SCAs (114). This conundrum was partially resolved after the discovery of bidirectional transcription of the SCA8 locus and subsequent translation of antisense transcripts (115). Yet one question remained unanswered: how can CAG repeats from antisense transcripts be translated without a start codon?

The discovery of an unusual phenomenon called repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation shed some light on this mystery (116). RAN translation requires neither the canonical nor an alternative start codon for initiation and results in production of repetitive proteins in all possible reading frames. Taking into consideration bidirectional transcription, one expanded repeat may produce up to six repetitive polypeptides. To illustrate, RAN translation of the GGGGCC repeat sense transcript, r(GGGGCC)exp, results in poly(GA), poly(GP), and poly(AR) peptides, all of which were detected in ALS/FTD patient–derived cells (117). The antisense transcription of the same repeat leads to accumulation of polyGP, polyAP, and polyPR peptides (118, 119). These polypeptides aggregate into high-molecular weight insoluble clusters (120) and seem to be neurotoxic (98, 121), although it is not yet clear to what extent different polypeptides contribute to overall toxicity (122).

Length-dependent RAN translation has been reported for CAG, CGG, GGGGCC, GGCCUG, and TGGAA repeats (reviewed in Refs. 123–125). Nonetheless, we still lack a good understanding of RAN's mechanistic details. One hypothesis is that formation of unusual secondary RNA structures, such as hairpins (114) or G-quadruplexes (G4s) (126), might somehow recruit ribosomes and trigger this peculiar mode of translation (Fig. 2).

Taken together, mechanisms by which expanded repeats lead to cellular toxicity include loss of function of a protein and a toxic gain of function on the RNA or protein levels. These mechanisms might take place in combination with each other. Unfortunately, for many REDs, there is still no consensus on what mechanism plays a major role in disease progression. For example, accumulation of toxic poly(Q) proteins was historically used to explain HD's phenotype. However, evidence accumulated in the last decade suggests that gain of function at the RNA level might also contribute to disease manifestation. This is supported by experiments in model systems where CAG repeats interrupted by the CAA codon express decreased cellular toxicity when compared with pure CAG repeat tracts (reviewed in Ref. 127). This is unexpected because both CAA and CAG codons code for glutamine. As such, the length of transcribed poly(Q) tracts does not depend on the presence of a CAA interruption. Additionally, it was recently documented that HD age of onset is better predicted by the length of uninterrupted CAG repeat tracts rather than by the sheer number of consecutive glutamines in the Htt protein (128–130). However, there exists an alternative explanation of the same phenomenon: the disease age of onset might depend on somatic expansions of CAG repeats during the patient's lifetime, a process that requires repeat integrity (see below).

Overall, due to technical obstacles, it is highly challenging to decipher the precise role of various toxicity mechanisms in a specific RED (125). Therefore, we have a good understanding of possible mechanisms of expanded repeats' toxicity, even though the precise mechanisms are established for only few REDs.

Dynamic DNA structures as the key to repeat instability

Tandem repeats are abundant in the human genome (131), particularly in centromeres and telomeres, as well as in regulatory regions (132). High variability of tandem repeats between different individuals (133) makes analysis of tandem repeat polymorphisms useful in forensics and paternity testing (134). Nonetheless, most of the known tandem repeats do not expand as dramatically as disease-causing repeats, which may gain up to thousands of repeat units in affected individuals (11, 54).

What are the main features that make certain repeats prone to large-scale expansions resulting in REDs? Numerous studies that we review below attempted to resolve this fundamental question. Initially, the DNA slippage model was proposed to explain instability of tandem repeats. It postulated that repeats may be lost or gained during local misalignment of DNA during replication or repair (135). Indeed, formation of slipped DNA structures followed by repeat unit gains was detected in in vitro replication experiments (136). These structures were also observed in DM1 patient samples (137).

The DNA slippage model is beautiful in its simplicity and sufficient to explain the small-scale instability of any tandem repeat. However, it does not easily address several questions. First, why do some repeats gain thousands of repetitive units and others do not? Second, why does the instability of expandable repeats increase exponentially but not linearly with the size of the repeat? And last, why do repeat interruptions dramatically stabilize expanded repeat tracts?

Relationship between repeat size and instability

Length-dependent instability is one of the most universal properties of expandable repeats. What is the nature of this relationship? The DNA slippage model predicts a linear correlation between a repeat's length and its propensity to expand or contract: the number of repetitive units should reflect the number of opportunities for local DNA strand misalignments. However, the expandable repeats' behavior is inconsistent with this prediction.

First, for the majority of expandable repeats, there exists a repeat number threshold length after which the repeat starts to exhibit dramatic intergenerational and somatic instability. Curiously, this threshold length is comparable with the average Okazaki fragment size in eukaryotes (138). Moreover, disease-causing repeats show a nonlinear relationship between the repeat length and instability in experimental systems. Depending on an experimental system, doubling the repeat tract length results in a 6.5-fold increase in instability for GGGGCC repeats (139), up to a 100-fold increase for CGG repeats (140, 141), and up to a 1000-fold increase for GAA repeats (142). Together, data from both patient samples and experimental systems demonstrate that there is a qualitative difference between the instability of long and short repeats. This difference is evident from the differential propensity of repeats to expand or contract, the scale of expansions and contractions, and, likely, mechanisms of expansions and contractions (reviewed in Ref. 143).

Role of repeat interruptions in repeat stability

The DNA slippage model predicts that a small number of repeat interruptions should not dramatically change the overall instability of a repeat. However, there appears to be a causal connection between repeat purity and length. Analysis of DNA samples derived from RED patients revealed that the expanded repeat tracts commonly lose repeat interruptions found in their ancestral alleles (also called long normal alleles). For example, (CGG)20–52 repeat alleles located in the FMR1 promoter are typically randomly interrupted by AGG triplets, whereas expanded alleles consist of almost pure CGG repeats (144). The presence of AGG interruptions stabilizes both normal and premutational CGG repeat alleles during intergenerational transmission (145–150) and in experimental systems (151). Overall, it seems like the total length of a pure uninterrupted CGG tract rather than the repeat length overall predicts the level of CGG repeat instability. In other words, a loss of AGG interruption likely predisposes CGG repeat tracts to large-scale expansions (149, 152). Generally, the stabilizing role of interruptions is common for expandable repeats and has been reported for GAA (153, 154), CAG (38, 128, 129, 155–162), CCTG (54, 58, 163–165), and other repeats in somatic tissues, intergenerational transmission, and experimental systems.

Taken together, it appears that DNA slippage cannot be solely responsible for the repeat instability observed in REDs. On the contrary, more complex mechanisms, likely involving formation of alternative DNA structures, should be involved. It is generally believed that formation of such structures allows certain repetitive sequences to escape faithful DNA replication or repair and to undergo large-scale expansion. These structures include DNA triplexes (also known as H-DNA), G4s, and imperfect hairpins. Some AT-rich sequences can also undergo major DNA unwinding; hence, they are called DNA-unwinding elements (DUEs) (Fig. 3).

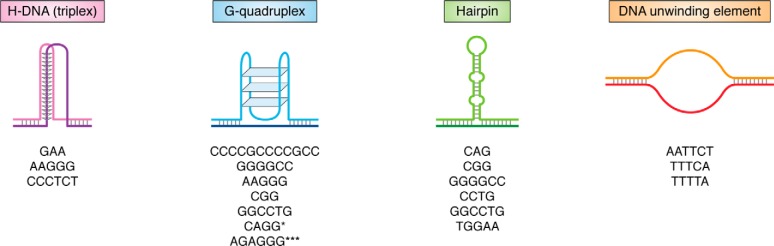

Figure 3.

Types of dynamic DNA structures and repeat sequences that form them. *, complement of CCTG; **, complement of CCCTCT.

H-DNA

As discovered in 1987, homopurine/homopyrimidine mirror repeats can adopt an intramolecular triple-helical DNA structure called H-DNA. In H-DNA, one of the DNA strands corresponding to one-half of the mirror repeat folds back, forming a triple helix with the remaining duplex part of the mirror repeat. The resulting triple helix constitutes a stack of base triads, which are stabilized by Hoogsteen or reversed Hoogsteen base pairing within the triplets and by π-π interactions between the stacks (Fig. 3). Two types of triplexes exist (166). First, a pyrimidine triplex, or H-y, consists of TA·T and protonated CG·C+ triads and requires a mild acidic environment to form (167). Second, a purine triplex, or H-r, consists of CG·G and TA·A triads and is stable at a physiological pH in the presence of bivalent cations (168).

H-DNA formation is favored in negatively supercoiled DNA, as it is topologically equivalent to DNA unwinding (169). Triplex-forming motifs are grossly overrepresented in eukaryotic genomes (170), which might point to their evolutionarily conserved role in genome function. On the other hand, formation of triplexes can pose a threat to a genome: triplexes impede DNA replication (171, 172) and transcription (73, 173, 174), promote formation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) (175), and trigger nucleotide excision repair (NER) (176). Three perfect homopurine-homopyrimidine repeats are known in REDs: GAA, AAGGG, and CCCTCT. GAA repeats are the best studied of the three and were reported to form both H-y and H-r triplexes in vitro and in vivo (177–182). Importantly, homopurine/homopyrimidine repeats that lack mirror symmetry (and therefore are unlikely to form stable triplexes) are dramatically more stable than (GAA)n repeats (183). This indicates that formation of a triplex might be central to repeat instability.

G4-DNA

One year after the discovery of H-DNA, a G4 structure was described for a GC-rich sequence from the immunoglobulin switch region (184). G4 is a four-stranded DNA structure, which consists of several G-quartets stacked upon each other and held together by π-π interactions. Each quartet is formed by four guanines connected by Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds (Fig. 3). Monovalent cations, specifically sodium and potassium, stabilize the G-quartets and their stacking interaction. The consensus motif is typically represented as G3N1–7G3N1–7G3N1–7G3, although G4-DNA with loops longer than 7 bp, with two G-tetrads, or with a bulged nonguanine base inside the three guanine tracts also is possible (reviewed in Ref. 185). G4 can exist in a large variety of isoforms differing in the number of DNA strands (one, two, or four) and relative strand polarity. In the context of this review, an intramolecular G4 structure is of prime relevance and is presented in Fig. 3.

G4 motifs are highly abundant in eukaryotic and some prokaryotic genomes (186). G4s were detected in vivo using G4-specific antibodies and small molecules. They are found in telomeres and multiple other regions in the genome (reviewed in Ref. 186) and are enriched in promoters and 5′-UTR sequences of genes. It is believed that G4s are likely to form in nucleosome-depleted, highly transcribed regions (187, 188). G4s interfere with regulation of transcription, genome integrity, and telomere maintenance (reviewed in Refs. 186 and 189–191). Importantly, they can constitute potent barriers for replication (reviewed in Ref. 192) and, in certain circumstances, promote DSB formation (193–195). Because these structures are highly stable at physiological conditions, a number of helicases, including Pif1, Rtel1, FANCJ, Bloom (BLM), and Werner (WRN), have evolved to unfold them (reviewed in Ref. 191). Additionally, various proteins, for example topoisomerase I (196–198) or nucleolin (199), can bind to and/or interact with G4 motifs (reviewed in Ref. 200).

Based on our knowledge of G-quadruplex structures and in vitro data, expandable repeats that should be able to readily adopt G4-DNA are GGGGCC (201–203), CCCCGCCCCGCG, AAGGG, and AGAGGG—the complement of CCCTCT. Other repeats, such as CGG (204), form a peculiar version of G4 composed of G-quartets separated by hydrogen-bonded cytosines. CAGG (the complement of CCTG) and GGCCTG repeats also have a potential to form a weak G4, in theory (Fig. 3).

Imperfect hairpins

An inverted DNA repeat may form a hairpin: a DNA secondary structure in which an upstream region anneals to a complementary downstream region via normal Watson–Crick base pairing. When hairpins form on either side of a double helix directly opposite to each other, the overall structure is called DNA cruciform. If two opposite hairpins are shifted relative to each other, the resulting structure is called slipped DNA or S-DNA (Fig. 4A). No expandable repeats can form a perfect hairpin or a cruciform. That said, many expandable repeats, such as CAG (205–207), CGG (204, 207), CCTG (208), GGGGCC (203), CCCCGCCCCGCG (209), and TGGAA (210), form hairpins containing mismatches—imperfect hairpins (Fig. 4A)—as was first demonstrated in a groundbreaking paper from the McMurray laboratory (207). Based on its sequence, another repeat, GGCCTG, also theoretically adopts an imperfect hairpin. Similar to perfect hairpins, complementary imperfect hairpins can also form an S-DNA (Fig. 4A).

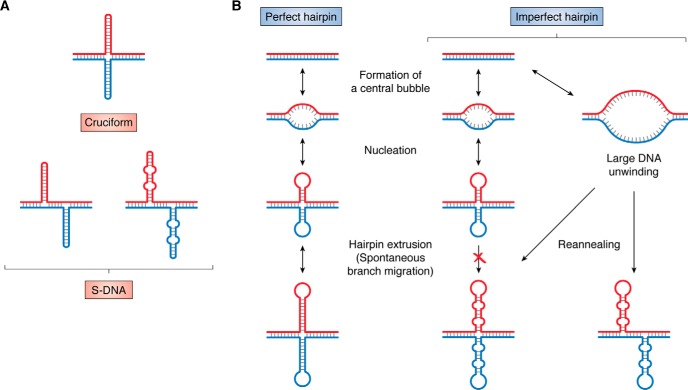

Figure 4.

A, DNA cruciform versus S-DNA structures. B, difference in the kinetics of perfect versus imperfect hairpin formation (see “Imperfect hairpins” in the “Dynamic DNA structures as the key to repeat instability” section).

Both DNA cruciform and S-DNA are topologically equivalent to completely unwound DNA and, thus, favored by negative DNA supercoiling. There is a principal difference, however, in their formation kinetics. In the case of a DNA cruciform, the first step is slow: it involves the unwinding of a ∼10-bp DNA segment around the pseudosymmetry axis of an inverted repeat to form a central bubble. Self-annealing of separated DNA strands in this bubble results in cruciform nucleation. The nucleus then quickly extrudes into the full-size cruciform via branch migration. Upon DNA linearization, DNA branch migration would instantly convert the cruciform back to a regular DNA duplex (211) (Fig. 4B).

The kinetics of S-DNA formation is different, owing to the fact that the presence of mismatches completely blocks spontaneous branch migration, thus precluding the extrusion step (212). Consequently, S-DNA formation must be preceded by the unwinding of a long DNA segment followed by the out-of-register self-annealing of individual DNA strands. In vitro, this could be achieved upon denaturing and renaturing of repetitive DNA segments. In vivo, this could happen during DNA replication, transcription, or repair, all of which involve unwinding of duplex DNA. After an S-DNA is formed, the same kinetic principles apply in reverse: the S-DNA cannot easily convert into duplex DNA via branch migration. In other words, such S-DNA is kinetically trapped and, thus, relatively stable even though this conformation is thermodynamically unfavorable (Fig. 4B).

DUEs

Highly AT-rich repeats ATTCT, TTTTA, and TTTCA are similar in their sequence composition to DUEs, which are involved in DNA unwinding at replication origins. Indeed, the DNA-unwinding capacity of the ATTCT repeat was confirmed experimentally. In supercoiled plasmids, this repeat is highly unwound or even completely unpaired, thus being accessible to small molecules, oligonucleotides, and DNA polymerase (213). In fact, long ATTCT can function as aberrant replication origins in human cells (214), which might contribute to their instability.

Taken together, all expandable DNA repeats can form dynamic DNA structures during biological transactions that involve either extensive DNA unwinding or accumulation of negative supercoiling (169, 215). Surprisingly, mechanisms of repeat instability are not the same for different repeats. These mechanisms depend on the repeat sequence, length, purity, and location within a genome, as well as cell type, developmental stage, and replicative and transcriptional status. Rephrasing Leo Tolstoy: stable DNA sequences are all alike; every unstable DNA sequence is unstable in its own way. In the next section, we review how the presence of expandable repeats affects genome integrity or, in other words, types of repeat-mediated genome instability.

Types of repeat-mediated genome instability

Length instability during intergenerational transmission

Expandable repeats change their length dramatically while being transmitted between generations. Some of them preferentially expand, which leads to the genetic anticipation phenomenon described above. Contrary to initial beliefs, however, most REDs do not exhibit genetic anticipation, and the repeat length changes in both directions between generations.

Remarkably, parental gender is the most significant determinant of the direction of intergenerational instability. For example, there is a strong bias for expansions of GAA (FRDA), CGG (fragile X), or CCCTCT (XDP) repeats during maternal transmission, whereas paternal transmission typically results in a contraction of the same repeats (31, 34, 140, 216–219). The opposite pattern is observed for the majority of diseases caused by CAG repeat expansions: repeats are stable or slightly biased toward contractions during maternal transmissions, whereas paternal transmissions are biased toward expansions (23, 24, 30, 159, 220–225). Note, however, that CAG repeats in SCA8 show the opposite tendency (114, 226), whereas CAG repeats in SCA2 (20) and SCA7 (16, 17) lack an apparent parental gender bias. Another interesting example is the ATTCT repeat: this repeat expands or contracts dramatically during paternal transmission but stays virtually unchanged during maternal transmission (227, 228).

The second important factor is parental age. Intergenerational instability of GAA (FRDA) (216), CTG (DM1) (229), and CAG (SCA17 (225) and SCA2 (224)) repeats directly correlates with parental age. DRPLA, SCA1, and DM1 mice also show age-dependent intergenerational CAG repeat instability (230–232). Having said that, age dependence is not a universal rule: for example, intergenerational instability of CAG repeats in HD depends neither on the mother's nor the father's age both in human (221) and mice (233) pedigrees.

Why does intergenerational repeat instability depend on parental gender and age? The increase of instability with age indicates that repeat expansions and contractions might take place before fertilization. This may simply be because a longer lifetime allows more chances for a repeat to contract or expand. Why repeat instability also depends on parental gender is a more difficult question for which we do not yet have a full answer. Several hypotheses that incorporate the differences between male and female germ cells were proposed to explain this phenomenon. First, the differential bias for expansions and contractions could be due to the differences in duration between spermatogenesis and oogenesis (230, 232, 234, 235). Second, the counterselection for repeat expansions could differ between sperm and oocytes (16, 218). For example, large-scale expansions of CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene seem to be counterselected in sperm (218, 236), possibly because FMR1 loss of function reduces sperm mobility, at least in Drosophila (237). Third, the difference in the expression level of certain DNA repair proteins such as Msh3 during spermatogenesis and oogenesis might explain different levels of repeat instability (238).

We hypothesize that two other mechanisms might account for the difference in repeat instability during spermatogenesis or oogenesis. First, a differential pattern of origin firing and replication timing might affect repeats' propensity to expand or contract (as will be discussed below). Second, the fate of chromatin, which is dramatically different between the two gamete types, could differentially affect repeat instability. Mature oocyte chromatin is very loose, to allow rapid production of RNAs and proteins required for successful fertilization and development into an embryo (reviewed in Ref. 239). In contrast, mature sperm chromatin is compact, owing to the temporary replacement of core histones with sperm-specific histone variants, followed by transition proteins and, finally, protamines (reviewed in Refs. 239 and 240).

Length instability in somatic tissues

The majority of REDs are not congenital; instead, they have a fairly late age of onset. It was initially thought that this is because repeat-associated toxicity is low and results in a slow, gradual degradation of patients' tissues that becomes symptomatic later in life (241, 242). Although certainly attractive, this hypothesis fails to explain two groups of data. First, it does not explain why the age of onset of dominant HD is well-predicted by the length of the longer repeat expansion allele in homozygous patients (243, 244) or why the age of onset of recessive FRDA is determined solely by the shorter GAA expansion allele (245–247). Second, it fails to explain why the age of onset of HD is better predicted by the length of noninterrupted CAG repeats in DNA rather than by the length of the polyQ tract in the protein (128–130).

The currently accepted view is that the age of onset and disease progression are governed by a combination of two different mechanisms (243). This hypothesis states that the number of repeats in inherited alleles is typically insufficient to exhibit significant cellular toxicity. However, repeats expand in some somatic tissues (16, 17, 27, 31, 32, 35, 36, 54, 80, 160, 248–251), which causes cell toxicity when a repeat length exceeds a disease-specific threshold. Subsequent disease progression is determined by the mechanism of toxicity, which is specific for each disease (252). This model provides an elegant explanation for the dependence of age of onset on the number of inherited repeats in both heterozygous and homozygous patients.

The level of somatic instability is tissue-specific (253, 254), likely because of differential expression of DNA replication and repair genes across various cells types (255). Somatic instability also depends on the type and length of the repeat (256) and tends to increase with age (54, 257, 258). Somatic instability can be so dramatic that it may preclude precise estimation of the initial repeat tract length (259): for example, the number of CTG repeats (DM1) may differ by 40–400 repeat units within one tissue and up to 5770 repeats between different tissues in a single person (253). In sum, it is the combination of the number of inherited repeats and the level of somatic instability that determine the age of onset for a particular disease and a particular patient.

Fragility and repeat-induced mutagenesis

DNA fragility is the propensity of a certain DNA sequence to promote chromosomal breakage (i.e. produce DSBs). Expanded CGG repeats located in the FRAXA, FRAXE, and FRA11B loci are renowned for their fragility (141). In fact, they were initially described as rare, folate-sensitive fragile sites (260–262). This is because they exhibit fragility under low-dNTP conditions, likely because DNA replication through expanded CGG repeats cannot compete with DNA replication of other genomic regions when the dNTP pool is limited (260). A less known fact is that many other repeats are also fragile. In model experimental systems GAA, CAG, and ATTCT repeats exhibit length-dependent fragility (263–268), whereas triplex-forming DNA sequences promote DSB formation in human cells (175). Additionally, breakpoints of genomic rearrangements in cancer are enriched for structure-forming tandem DNA repeats, such as (AT)n, (GAA)n, and (GAAA)n (269).

What could be the consequences of a DSB formation? Generally, error-prone repair of a DSB provides many opportunities for mutagenesis. Notably, mutations may arise kilobases away from the DSB site (reviewed in Ref. 270). As such, fragile, repetitive tracts could induce mutagenesis at a distance, a phenomenon that we have termed RIM (271). Long CGG repeats are highly prone to RIM. Based on patient data, they facilitate large chromosomal deletions (272, 273), chromosomal arm loss (262, 274), and even a loss of a whole X chromosome. The latter is evidenced by an unusually large proportion of fragile X females with mosaic Turner syndrome (273, 275). Furthermore, using an experimental system to detect CGG-mediated repeat instability in human cells, we recently confirmed accumulation of point mutations up to 3 kb away from the repeat (276). Other structure-forming repeats also seem to exhibit RIM. Data from FRDA patients also show that GAA repeats elevate the number of point mutations in the genomic areas surrounding the repeat locus (277). In yeast, repair of DSBs formed within expanded GAA repeats results in the accumulation of point mutations located more than 1 kb away from the repeat (138, 264, 268), large deletions (264), and gross chromosomal rearrangements (278). Finally, a recent study has found that somatic expansions of TTTCA repeats in FAME3 patients are concurrent with small and large genomic rearrangements (32).

As of today, most research on REDs focuses exclusively on changes in repeat lengths. However, two different repeats, GAA and TTTCA, whose fragility has never been directly observed in humans, likely promote RIM in RED patients (32, 277). Therefore, we believe that repeat fragility and RIM are important and overlooked factors in RED progression and pathology.

In sum, expandable DNA repeats demonstrate profound length instability during both intergenerational transmissions and somatic cell divisions. They also cause chromosomal fragility, induce mutagenesis at a distance, and trigger formation of complex genome rearrangements. In the next section, we discuss the role of DNA replication, transcription, repair, and chromatin environment in these phenomena.

Role of DNA replication in repeat instability

Duplicating long structure-forming repetitive sequences presents a significant challenge for the replication machinery. This phenomenon is well-established and has been observed in virtually all experimental systems. In this section, we review how replication contributes to repeat instability.

Evidence that replication promotes repeat instability

In experiments with mammalian cells, long GAA (279) or CAG (280) repeats cloned into plasmids expand and contract more frequently if the plasmids are able to replicate upon transfection. This indicated that replication per se promotes repeat instability.

DNA replication is inherently asymmetrical. Whereas the nascent leading strand is synthesized more or less continuously in the direction of replication, the nascent lagging strand is replicated in the opposite direction and in short patches known as Okazaki fragments. Consequently, a floating zone in the lagging strand template called the Okazaki initiation zone stays single-stranded, facilitating the formation of DNA secondary structures. There are also differences in DNA polymerases that synthesize the two DNA strands. The leading strand DNA polymerase ϵ (Pol ϵ) is a highly processive and precise enzyme. The lagging strand DNA polymerase δ (Pol δ) is less processive, and its fidelity is an order of magnitude lower than that of Pol ϵ, which is compensated by a higher activity of mismatch repair (MMR) on the lagging strand. Unlike Pol ϵ, Pol δ has strand displacement activity, which is needed for Okazaki fragment processing (reviewed in Ref. 281). To additionally complicate the picture, it was recently demonstrated that leading strand DNA synthesis is, in fact, initiated by Pol δ followed by a switch to Pol ϵ (282).

Not surprisingly therefore, the asymmetry of the replication fork leads to orientation-dependent repeat instability. Indeed, CAG/CTG repeats tend to contract if the CTG tract is in the lagging strand template and tend to expand if the CAG tract is in the lagging strand template in bacterial (35, 283), yeast (161, 162, 284, 285), and mammalian cells (206, 280, 286). Typically, this orientation dependence is explained by the fact that an imperfect hairpin formed by a (CTG)n tract is more stable than the one formed by a (CAG)n tract. Thus, when a (CTG)n tract is located in the lagging strand template, DNA polymerase might somehow jump through a hairpin formed by this repeat, resulting in a contraction. Alternatively, when the (CTG)n tract is in the nascent DNA strand during lagging strand replication, it can form slipped hairpins that, if unrepaired, would lead to expansions (reviewed in Ref. 287). Similarly to CAG repeats, the CGG and GGGGCC repeats form imperfect hairpins, and the hairpins formed by the G-rich strands are more stable (287). In addition, the G-rich strand of these two repeats may fold into a G4 (201–204). Consistent with the formation of a hairpin or a G4 during lagging strand synthesis, several studies have found that when located in the lagging strand template, CGG (141, 151, 288, 289) and CCGGGG (139) tracts are prone to repeat contraction. GAA repeats do not fold into a hairpin or a G4 and instead form an H-DNA. They also undergo orientation-dependent instability. In a majority of studies, GAA repeats are more unstable when (GAA)n tracts are located in the lagging strand template (73, 142, 153, 290), although we recently found that there is almost no difference in the repeat contraction rate among the two orientations (183).

Altogether, the dependence of repeat instability on the orientation relative to the origin of replication led us to propose the “ori-switch” model. It postulates that inactivation of a replication origin on one side of a repeat and the subsequent switch to the origin located on its opposite side changes the pattern of repeat instability, predisposing them to either expansions or contractions (292).

Repeat instability also strongly depends on the distance between the repeat and the nearest origin of replication (206, 208, 214, 284, 286, 293). The mechanisms of this dependence are not well-understood. Our “ori-shift” model (292) posits that this may be caused by the differences in repeat position within the Okazaki initiation zone. Given recent observations (282), this may also be caused by the repeat position relative to the location where Pol δ switches to Pol ϵ during leading strand synthesis.

Overall, it seems highly likely that a repeat's position within the replicon should play a big role in repeat-induced pathogenesis in humans. First, the “ori-switch” and “ori-shift” models explain why the same repeat tract exhibits dramatically different patterns of instability in two different locations in the genome (250, 279). Second, it could explain time- and tissue-specific differences in repeat instability. For example, the fragile X CGG repeat is believed to expand and contract during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis but stays relatively stable later in a person's life (60, 272, 294–297). Tissue-specific differences in origin-firing patterns might explain why CGG instability is limited to such a narrow developmental window. It is possible that during embryonal development, the CGG repeat is in an unstable position relative to the active origin of replication. During later cell division, a different origin might be utilized, thus fixating repeat length (298, 299). Additionally, expanded CGG repeats may themselves influence activation of the near origins and, as such, put themselves in an unstable position (82). This hypothesis explains the existence of a length threshold required for CGG repeat instability.

Role of Okazaki fragment processing in repeat instability

Another piece of evidence for the role of replication in repeat instability comes from the observation that impaired Okazaki fragment processing destabilizes various types of repeats, at least in yeast. During lagging strand replication, Pol δ partially displaces the 5′-end of a preceding Okazaki fragment while replicating the succeeding fragment. Specific 5′ flap endonucleases then process the flap, which is followed by the ligation of two fragments. In yeast, two endonucleases do the bulk of the job: Rad27, which only cuts short flaps (300–302), and Dna2, which cuts longer flaps (301–306). Mutations in either of these nucleases lead to dramatic increases in the expansions of various repeats, including CAG, GAA, CGG, G, GT, CAGT, CAACG, CAATCGGT, yeast telomeric repeats, and several minisatellites (142, 289, 307–318). In other words, the effect of rad27 or dna2 mutations is virtually independent of the repeat sequence. The classic interpretation of these data involves the incorporation of a long repetitive flap into the nascent strand during DNA replication, resulting in an elongated repeat tract (319) (Fig. 5A). However, the same mutations also increase repeat contraction rates (183, 289, 307, 309, 310, 312–314, 316–318), a phenomenon that cannot be explained by the flap incorporation model. A more general model suggests that in the absence of fully functional Rad27 or Dna2, the genome-wide accumulation of long ssDNA species (314, 320, 321), such as flaps or gaps, titrates the ssDNA-binding protein replication protein A (RPA) from the repetitive regions (322). Due to the lack of RPA, transiently formed ssDNA within the repetitive tracts is likely to equilibrate into DNA secondary structures, which trigger repeat instability (Fig. 5B) (183).

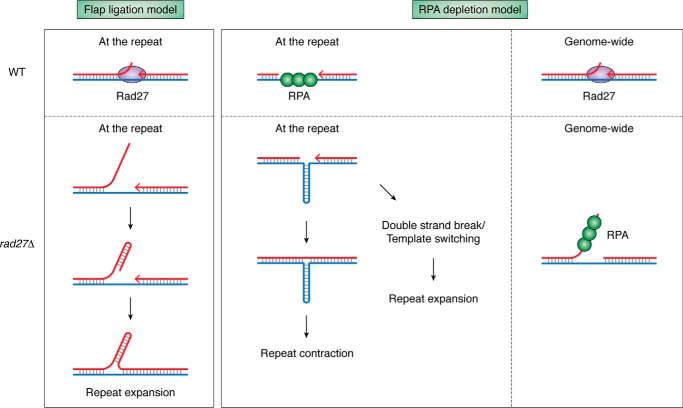

Figure 5.

Two models depicting the potential role of Rad27 flap endonuclease in the instability of structure-forming repeats. A, flap ligation model. In the absence of Rad27, long flaps that formed during Okazaki maturation might become incorporated into the nascent DNA during lagging strand synthesis, resulting in repeat expansion. B, RPA depletion model. In the absence of Rad27, long flaps that accumulate genome-wide during Okazaki fragment maturation titrate RPA out from the repetitive DNA. This promotes formation of DNA secondary structures (the hairpin is shown) within the repeat and can result in repeat contraction or expansion.

Are these models applicable to humans? The yeast Rad27 and human Fen1 proteins are highly conserved, such that Fen1 overexpression rescues the rad27Δ phenotype in yeast (323). However, despite these similarities, attempts to find mutations in the FEN1 gene that modify the phenotype of CAG repeat expansion in HD patients were fruitless (324–327). Surely, failure to identify such modifiers could potentially be explained by the high toxicity or lethality of FEN1 mutations. However, experiments with siRNA knockdown of Fen1 in a cell line system (328–330) and with Fen1-deficient mice generally do not detect a role for Fen1 in CAG repeat stability (331), except for one study where the nuclease activity of Fen1 was found to counteract CAG repeat instability, although the effect was not as dramatic as in yeast (332). Additionally, knockdown of Fen1 in mammalian cells does not promote GAA repeat instability.3 Therefore, there could exist fundamental differences between yeast and humans, either in the Okazaki fragment processing pathways or in the regulation of RPA homeostasis.

Direct evidence that expandable repeats are hard to replicate

Contemporary techniques, such as quantification of nascent strand abundance, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, EM, and single-molecule visualization of replicating DNA allow researchers to directly measure replication fork progression. These techniques unconditionally proved that expanded tracts of CAG, GAA, CGG, and GGGGCC repeats physically stall the replication fork in a length-dependent manner in every experimental system studied, including bacterial, yeast, and mammalian cells. Notably, the effect is most pronounced for the CGG and GGGGCC repeats (73, 139, 290, 333–341). How do expanded repeats stall the replication fork? First, replication through a long repetitive sequence might exhaust the local dNTP pool, which slows down the replisome (342). Second, and even more important, DNA sequences prone to form alternative DNA structures block replication both in vivo and in vitro, particularly when their purine-rich strands are in the lagging template (171, 343). Third, these alternative DNA structures may recruit various proteins, which could create “protein bumps” that impede replisome progression (335).

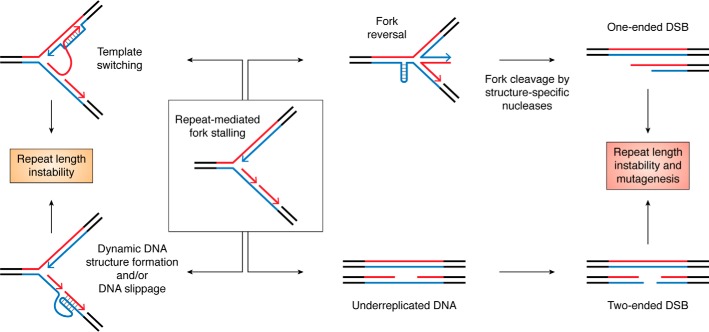

What happens after the replication fork has stalled depends on the repeat sequence, replication mode, and other cellular factors. Consequently, the amount of fork stall may (290) or may not reflect the amount of repeat instability (139, 335, 340). In the best-case scenario, the replication fork can temporarily slow down but quickly recover and continue DNA replication as if nothing had happened. However, a longer pause may lead to the formation of single-stranded gaps, which might result in the accumulation of mutations around the repeat tract (Fig. 6). A prolonged stall can, in turn, facilitate DNA slippage or template switching, both of which can lead to repeat length instability. During template switching, a stalled replicative polymerase, either Pol δ or Pol ϵ, temporarily switches its template and replicates from the nascent strand to bypass a lesion. If a polymerase stalls at a repetitive template, it might invade the opposite strand out of register and thus end up synthesizing the wrong number of repeats (reviewed in Ref. 344) (Fig. 6). Data from our laboratory revealed that this process could be responsible for GAA repeat expansion in yeast (142).

Figure 6.

Possible mutagenic consequences of fork stalling within structure-forming repeats (see “Direct evidence that expandable repeats are hard to replicate” for details).

A dramatic consequence resulting from the replication fork colliding with a potent barrier is fork reversal (345). Fork reversal is a process in which two nascent strands anneal to each other, whereas their template strands reanneal back (Fig. 6), resulting in the formation of the so-called “chicken foot structure” containing a four-way junction. The biological role of fork reversal is to allow a bypass of a DNA lesion in a template strand using an unperturbed nascent strand as a temporal template (reviewed in Ref. 345). Formation of dynamic DNA structures could serve as such a lesion, as reversed forks were detected in vivo for CAG (346) and GAA repeats (338). Furthermore, formation of a reversed fork could promote repeat instability. Indeed, transition of a normal replication fork into a chicken foot structure involves several strand-reannealing steps and as such provides multiple opportunities for potential misalignment of tandem repeats. Furthermore, chicken foot structures are substrates for structure-specific nucleases, which can transform reversed forks into one-ended DSBs. These DSBs must be repaired through break-induced replication (BIR), a conservative mode of DNA replication, which leaves its mutagenic trace as much as several kilobases away from the initial break site (reviewed in Ref. 347) (Fig. 6).

If the replication fork cannot recover from a stall, it leaves unreplicated ssDNA regions that can be broken into a two-ended DSB (Fig. 6), which would need to be repaired via homologous replication (HR). However, mitotic cell division may start before a DSB is formed. This is common for late replicating fragile sites, like the CGG repeat in the FMR1 promoter (348). In this scenario, ssDNA regions transform into anaphase bridges, which may lead a permanent loss of a part of or even a whole chromosome (261, 341).

How to maintain hard-to-replicate expandable repeats?

Cells have evolved a number of mechanisms to minimize fork stalling and ensure, as much as possible, smooth progression of the replication fork through repetitive DNA. Replication fork–stabilizing factors, Tof1 and Mrc1, prevent CAG repeat instability and fragility of CAG, ATTCT, and GAA repeats in yeast (142, 263, 308, 349). In addition, specific helicases assist replisomes by unwinding unwanted DNA secondary structures.

Yeast helicases Srs2 and Sgs1 unwind hairpins formed by CTG and CGG repeats in vitro, with Srs2 being more efficient (350). In vivo, knocking out SRS2, but not SGS1, promotes instability and fragility of CAG and CGG repeats (351–353), although some reports found that Sgs1 also maintains CAG (354) and CGG repeat stability (289). Despite this disagreement between studies, the amounts of CAG repeat instability in srs2Δ or sgs1Δ mutants reflect the amount of fork stalling. Furthermore, human helicase Rtel1, which unwinds hairpins formed by CAG repeats and complements the yeast srs2Δ mutant, prevents CAG repeat expansions in human cells (355). These observations support the model in which Srs2/Rtel1 and, to a lesser extent, Sgs1 helicases unwind DNA hairpins during DNA replication to prevent fork stalling. Interestingly, the secondary structure–unwinding activity of Srs2 and Sgs1 seems to be specific to hairpin unwinding. Indeed, the instability and fragility of non-hairpin-forming repeats, such as telomeric or GAA repeats, does not depend on Srs2 (142, 183, 351) and is mildly affected by Sgs1, if at all (142). It is not yet known whether there are other helicases that unwind DNA hairpins. Recently, for example, human DNA helicase B was reported to localize to replication stalls at CGG repeats (356), although direct evidence that this helicase unwinds hairpins is so far absent.

Can other DNA secondary structures such as G4 or triplex also be unwound by specialized helicases? Because G4 is so stable under physiological conditions, there is a team of helicases that unwind this structure. This team includes FANCJ, Rtel1, BLM, and Pif1, to name just a few (reviewed in Refs. 191, 192, and 357). Triplex-unwinding helicases, on the other hand, are still largely unknown. Reports have demonstrated in vitro triplex-unwinding activity for several proteins, namely human Dhx9 (358), Ddx11 (359), and BLM and WRN helicases (360) as well as the yeast Stm1 protein (361). However, in vivo evidence for the involvement of these helicases in triplex unwinding is scarce. In particular, data from our laboratory did not show evidence for Stm1 and Chl1 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ddx11) triplex-unwinding activity in yeast in vivo (183).

Role of transcription in repeat instability

Remarkably, expandable repeats can exhibit instability in the absence of replication (257, 362), and, in some circumstances, transcription through expandable repeats is sufficient to destabilize them. As a matter of fact, transcription through expanded repeats promotes their fragility (257, 363), instability (154, 330, 364–367), and RIM (368). On the face of it, this phenomenon seems unexpected, considering that there is no DNA synthesis involved in transcription. Nonetheless, transcription can affect repeat instability via at least three different mechanisms. First, transcription can change the chromatin landscape and, as such, alter repeat stability indirectly (see below). Second, the Smith laboratory recently showed that DNA replication often initiates at transcription start sites in human cells (369). This means that transcription determines origin-firing patterns, which could directly control repeat instability (see above). Third, formation of transcription-dependent R-loops directly influences repeat instability.

An R-loop is a DNA-RNA hybrid that forms during transcription when a nascent RNA strand invades the DNA duplex and reanneals to its template DNA via normal Watson–Crick base pairing. In a eukaryotic cell, R-loops act as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they play an important role in the regulation of gene expression and transcription termination. On the other hand, they can stall replication and transcription, promote replication-transcription collisions, and, as such, lead to DSB formation and genome instability (reviewed in Refs. 370 and 371).

In vitro, transcription through CAG, CGG, and GAA repeats induces single and double R-loops. The amount and size of these R-loops correlate with an increase in negative supercoiling upstream of an elongating RNA polymerase (365, 372). R-loops are also detected at expanded GAA, CGG, GGGGCC, and CAG (72, 373) repeats in patient samples as well as in several experimental systems (79, 365). Most importantly, R-loop formation within long repeats likely promotes their instability. This is evidenced by the fact that RNase H, which degrades R-loops, counteracts repeat instability (75, 365, 374).

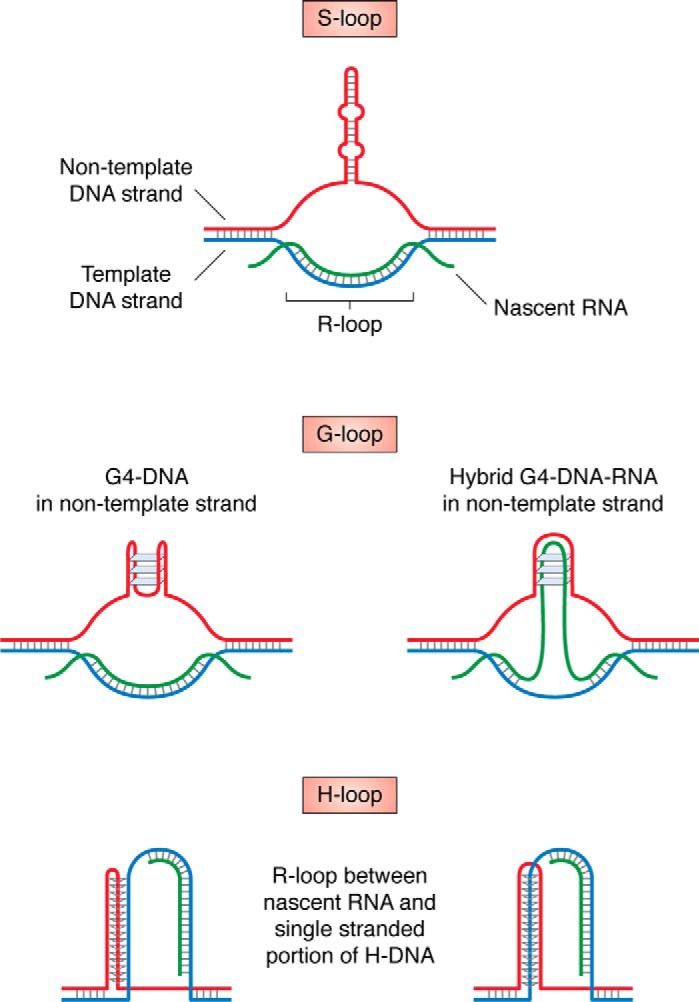

How can formation of R-loops lead to repeat destabilization? When an R-loop forms on a template strand, it leaves the complementary part of the DNA duplex single-stranded, thus promoting the formation of dynamic DNA structures. The result is a composite DNA structure consisting of an R-loop and an alternative DNA structure (Fig. 7) that facilitates repeat instability. For example, formation of a DNA hairpin opposite to an R-loop strand (S-loop) was suggested to explain the R-loop–induced instability of CAG and CGG repeats (79, 365, 374). In a G4-forming repeat, a structure called a G-loop is possible. It can come in two flavors: either G4-DNA is formed in the nontemplate strand, or a hybrid G4-DNA-RNA structure is formed between the nontemplate DNA and a nascent RNA strand. Such structures might form in human cells with expanded CGG and GGGGCC repeats (373, 375). Likewise, a triplex-forming repeat might form an H-loop; in this structure, an R-loop is formed between an RNA transcript and a single-stranded portion of H-DNA (74, 75) (Fig. 7). Collision between a replication fork and an H-loop formed by a GAA repeat might lead to the formation of a DSB, followed by repeat expansion in the course of BIR (75).

Figure 7.

Various R-loop-based structures formed by expandable DNA repeats (see “Role of transcription in repeat instability” for details).

Another level of complexity is added by the fact that most of the mammalian genome is bidirectionally transcribed (376, 377), and repetitive regions are no exception (115, 378–380). Bidirectional transcription was detected for CAG (381–384), CGG (380, 385), GGGGCC (379), and other repeats (reviewed in Ref. 378) and can synergistically destabilize them (386), likely due to formation of double R-loops (387).

Role of DNA repair in repeat instability

Replication and/or transcription through expanded repeats fosters the formation of DNA secondary structures, which might lead to the formation of a DNA nick or a DSB. This DNA damage then serves as a substrate for various pathways of DNA repair. Consequently, DNA repair plays an important role in repeat instability.

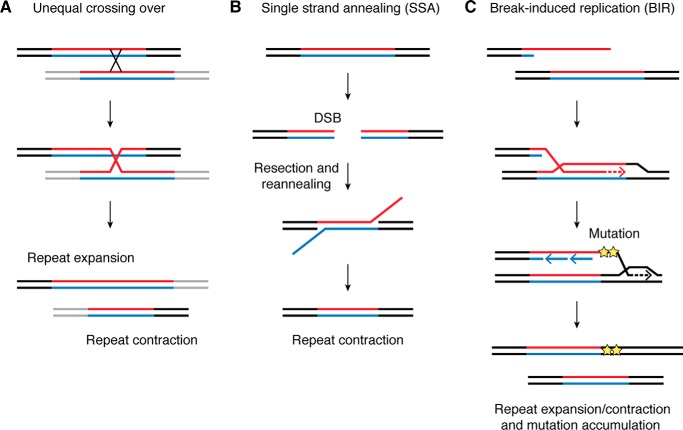

HR

As discussed above, structure-forming repeats promote DSBs either during replication or transcription through the repeat. Thus, it is not surprising that these repeats serve as hotspots for homologous recombination in Escherichia coli (388–393) and yeast (394). These recombination events are often accompanied by a repeat length change (388, 390, 392, 395–398), likely because of an out-of-register strand invasion during the classical HR. However, in yeast, the majority of unstable repeats are not hotspots for recombination during meiosis (289, 394, 399), and their barely detectable meiotic instability depends on the Spo11 nuclease (267, 400). Data from human (401, 402) and mouse (403, 404) pedigrees also agree that repeat instability generally does not arise from unequal crossing over. A notable exception to this rule is poly(A) diseases, which are caused by expansions of GCN repeats (46, 47, 50, 52, 53). In this case, expanded alleles likely originate via unequal crossing over between parental repeats (44, 51, 52, 109, 398) (Fig. 8A). This explains the lack of detectable somatic instability of GCN repeats as well as their small scale of expansion.

Figure 8.

HR mechanisms implemented in repeat instability. A, as a result of an unequal crossing over during meiosis, one homologous chromosome inherits a contracted repeat tract, whereas another inherits an expanded repeat tract. This mechanism is typical for poly(A) diseases. B, a DSB initiated at a repetitive sequence is followed by end resection and reannealing of the repetitive ends. This can ultimately result in repeat contraction. C, a one-ended DSB can be repaired via BIR. Out-of-register invasion into a repetitive template can give rise to both expansions and contractions, while point mutations accumulated in the course of BIR are responsible for the RIM phenomenon.

Besides canonical HR, two other pathways, single-strand annealing (SSA) and BIR, were implicated in repeat instability. The SSA pathway involves the resection of DSB ends followed by the annealing of flanking direct repeats, which normally results in a deletion. SSA does not require strand invasion performed by Rad51, but it does require strand annealing by Rad52 or Rad59. As such, one would expect this pathway to give rise to repeat contractions, rather than expansions (Fig. 8B). Indeed, an artificial induction of a DSB within a repetitive tract drives repeat contractions via SSA (396, 405, 406).

The BIR pathway is a highly error-prone, conservative mode of DNA replication that specifically repairs one-ended DSBs. BIR is identified by its mutational signature and dependence on Rad52 recombinase and a processivity subunit of DNA polymerase δ, Pol32 (PolD3 and PolD4 in mammals) (reviewed in Ref. 347). We have recently shown that in yeast, large-scale expansions of CAG repeats (407) and transcription-induced expansions of GAA repeats (75) happen through BIR. Moreover, BIR drives instability of carrier-size CGG repeats in a mammalian cell culture system (276). In the latter case, small-scale expansions and contractions of CGG repeats are accompanied by point mutations and complex rearrangements in the reporter gene. In all of these scenarios, BIR is likely triggered by a secondary structure formation at the repeat locus, and mutations accumulate during error-prone synthesis by Pol δ (Fig. 8C). Aside from BIR, RIM spanning to kilobases away from the repeat can also arise via a different mechanism. Replication through a repeat can leave behind a long single-stranded gap to be filled in by an error-prone translesion polymerase (264, 268, 389).

Importantly, structure-forming repeats not only promote recombination, but can also interfere with it. Any recombination event has to start with resection and typically involves ssDNA end invasion. If this end readily folds into a secondary structure, it could impede the recombination process (408). Unusual DNA structures may inhibit later stages of HR as well. For example, triplexes inhibit branch migration of Holliday junctions in vitro (409).

End-joining (EJ) pathways

In addition to various HR pathways, cells have evolved several EJ pathways to repair DSBs. As follows from the name, EJ pathways involve the direct fusion of two broken DNA ends. The classic pathway, named nonhomologous EJ (NHEJ), involves threading the DNA into Ku70/80 protein rings followed by the direct ligation of the two DNA ends with DNA ligase IV. This pathway leads to a virtually error-free mode of repair. However, when ends cannot be directly ligated, they need to be processed. This can result in small (up to 4-bp) deletions. In a situation when NHEJ cannot be executed, cells employ more error-prone, noncanonical variations of EJ pathways, such as alternative NHEJ, microhomology-mediated EJ (MMEJ), or synthesis-mediated MMEJ (reviewed in Ref. 270). We do not yet know all of the details and differences between these mechanisms, but what they have in common is that they (i) are highly error-prone and typically result in indels up to 20 bp in size, (ii) do not require classic NHEJ mediators such as Ku70/80 proteins or DNA ligase IV, and (iii) typically act when classic NHEJ is compromised (reviewed in Refs. 270 and 410).

The classic NHEJ seems to be protective against repeat instability, as evidenced by experiments with CAG repeats in yeast (395, 411) and CGG repeats in mice (412). Probably, NHEJ directly ligates a subset of DNA ends originated from a DSB within a repeat, without an alteration in repeat length. Otherwise, these ends would have been repaired via repeat-destabilizing HR or noncanonical EJ pathways.

How can noncanonical EJ pathways destabilize repetitive sequences? It was found that Pol β, which might participate in MMEJ (413), promotes CAG repeat expansions in vitro (414). Knocking down key alternative NHEJ modulators, namely XRCC1, LIG3, and PARP1, suppresses CAG repeat contraction induced by environmental stresses, such as cold, heat, and hypoxia, in human cell cultures (329).

At first glance, it might seem that HR plays a much bigger role in repeat instability than EJ pathways. However, this may simply reflect the fact that most mechanistic studies regarding repeat instability were primarily conducted in replicating yeast or mammalian cells. In replicating cells, DSBs typically arise during DNA replication and are predominantly repaired via HR pathways. Independent of replication, specifically in G0 and G1 cell cycle stages, DSBs originate in the course of transcription and result from oxidative damage to DNA. These breaks are typically repaired via EJ pathways (reviewed in Refs. 415 and 416). To fully elucidate the relative contributions of HR and EJ in repeat instability, one needs to carefully compare repeat instability between isogenic replicating and nonreplicating cells.

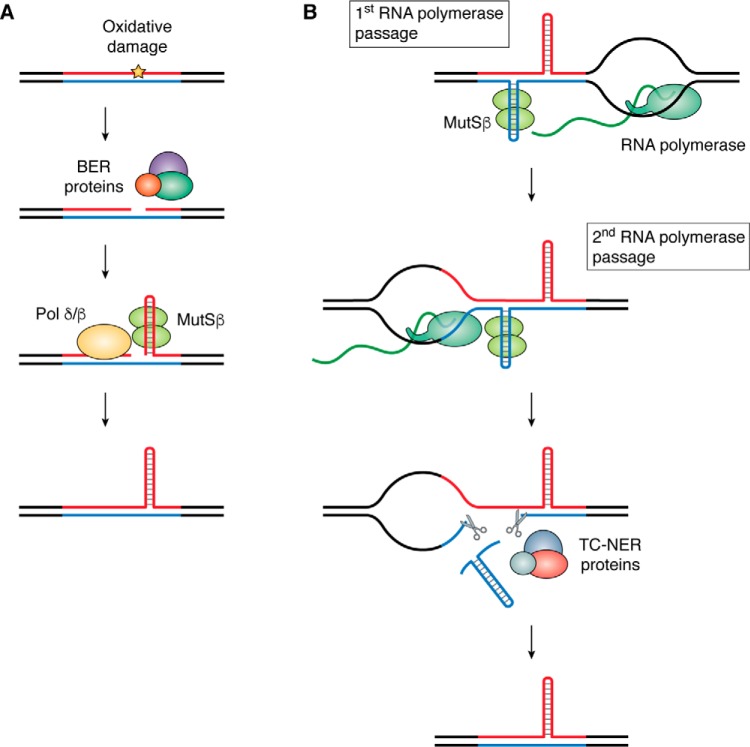

MMR

MMR recognizes and fixes mismatches as well as small loop-outs that distort the double-helix structure. In eukaryotes, mismatch repair starts by the binding of MutS complexes that recognize a lesion. Mismatches and 1–3-bp loop-outs are recognized by the MutSα (Msh2 and Msh6), and larger loop-outs are recognized by MutSβ (Msh2 and Msh3). Upon mismatch recognition, one of several MutL complexes excises the lesion to allow Pol δ to fill the resulting gap (reviewed in Ref. 417). Mutations in MMR give rise to Lynch syndrome, an autosomal dominant disease associated with a high risk of colon cancer. On the molecular level, Lynch syndrome is characterized by high microsatellite instability: the patients have a higher rate of length instability among various short tandem repeats (reviewed in Ref. 418).