Abstract

The green synthesis of the flavor esters, n-propyl acetate, isobutyl acetate and isoamyl acetate had the advantages over the chemical synthesis. The esterase from Candida parapsilosis could transform n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol into n-propyl acetate, isobutyl acetate and isoamyl acetate, respectively. The esterase was expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. At 30 °C for 1 d, the concentration of n-propyl acetate, isobutyl acetate and isoamyl acetate synthesized by the esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae was 24.6 mg/100 mL, 8.3 mg/100 mL, 5.6 mg/100 mL, respectively. Expression of the esterase has a practical significance for flavor ester synthesis by green biochemical process.

Keywords: Flavor ester, Esterase, Candida parapsilosis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Introduction

The flavor esters, isoamyl acetate, isobutyl acetate and ethyl acetate, have important applications in the food industry [1–4]. Isoamyl acetate has the characteristic banana flavor. Isobutyl acetate has the combined smell of pear and red raspberry. Ethyl acetate has a strong smell of banana. The three kinds of the esters are three kinds of the ingredients which widely used in food industry. For example, isoamyl acetate used in food production was over 75,000 kg/year [5].

The flavor esters could be extracted from plants. This extraction was costly and caused environmental pollution. The flavor esters could also be produced by chemical synthesis [6, 7]. Chemical synthesis had high productivity and large production, but the process caused also serious environmental pollution [8]. Compared to the extraction process or chemical synthesis, biochemical catalysis processes are greener or more environmentally compatible. Furthermore, biochemical catalysis processes are the milder techniques. The milder reaction conditions reduced the energy requirements. Some flavor compounds have been produced by biochemical catalysis processes [9].

Enzymatic synthesis, a typical biochemical process, has the advantages of low energy consumption, few by-products, high efficiency and high selectivity [10–13]. Many chemicals productions were efficiently produced with some industrial enzymes [14]. Enzymatic synthesis was a desirable process to produce the flavor esters.

Some kinds of esterase, which derived from animal, plant and microbial, could synthesize some esters in organic solvent solution [15, 16]. Excellent esterases are totally indispensable for ester production by biochemical process. Plants, animals and microorganism could produce excellent esterase, but the extraction process of esterase derived from animal or plant is cumbersome and relatively expensive [17–19]. The esterases from microorganism have advantages in cost, compared to plant derived or animal derived esterase. The esterase which could synthesize isoamyl acetate, isobutyl acetate and ethyl acetate has not been reported.

In this work, Candida parapsilosis esterase was selected and efficiently expressed to esterify n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol into the correspondent esters.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Media

The strain Candida parapsilosis was isolated from a marine sediment sample from the East Sea coast of China.

Selection medium was composed of 10.0 g peptone, 5.0 g yeast powder, 10.0 g NaCl, 2.0 mL tributyrin, 20.0 g agar powder, 1.0 L tap water. 2216E medium was composed of 10.0 g peptone, 3.0 g beef extract, 5.0 g glucose and 1.0 L seawater. LB medium was composed of 10.0 g tryptone, 5.0 g yeast extract, 10.0 g NaCl and tap water 1.0 L. The pH was adjusted to 7.0. SD-uracil medium was composed of YNB of 6.7 g/L, 40 mg/L sulfate adenine, 20 mg/L arginine monohydrochloride, 100 mg/L aspartic acid, 100 mg/L glutamic acid, 60 mg/L leucine, 30 mg/L lysine, 20 mg/L methionine, 50 mg/L phenyl alanine, 375 mg/L serine, 200 mg/L threonine, 40 mg/L tryptophane, 30 mg/L tyrosine, 150 mg/L valine, 100 mg/L histidine, and 20.0 g/L glucose, 2.0 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 1.0 L tap water. YNB medium was composed of 2.0 mg/L inose, 0.4 mg/L nicotinic acid, 0.4 mg/L thiamine niacin, 0.04 mg/L CuSO4, KH2PO4 1000 mg/L, H3BO3 0.5 mg/L, 0.4 mg/L vitamin B6, 0.4 mg/L vitamin B5, 0.2 mg/L aminobenzoic acid, 500 mg/L MgSO4, 0.4 mg/L MnSO4, 0.4 mg/L ZnSO4, 0.2 mg/L FeCl3, 0.2 mg/L lactoflavine, 100 mg/L CaCl2, 0.1 mg/L KI, 0.2 mg/L NaMnO4, 0.002 mg/L biotin, 100 mg/L NaCl. YPD medium was composed of 5.0 g yeast powder, 10 g peptone, 20 g glucose, 1.0 L tap water.

Selection of Esterase Producing Strain

1.0 g sediment samples were diluted with sterilized seawater. 100 μL of the diluted samples were spread on selection medium plates and cultured at 20 °C. The esterase usually showed lipase activity and could hydrolyze tributyrin in selection medium. When tributyrin was hydrolyzed by esterase from the colonies, transparent circles around the colonies could be seen. The colonies with the transparent circles were picked out and transferred into 2216E medium. The strain showing the esterase activity was selected as the esterase producing strain.

Genome DNA Extraction and ITS Sequence PCR

The genomic DNA of the esterase producing strain was extracted. The internal transcribed spacers (ITS) sequence was amplified using the primers: 5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′ and 5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′. PCR products were detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and were recovered by DNA gel recovery kit.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction

The blast program was used to search the similar sequence present in non-redundant database. The type strain sequences of the similar species were selected from GenBank and aligned using Molecular Ecolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 (MEGA7). Neighbor-Joining method was used to construct a phylogenetic tree with Kimura two-parameter model [20, 21].

Total RNA Extract and RT-PCR Amplification of Esterase

Candida parapsilosis was inoculated into YPD medium and cultured at 30 °C for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted according to the instructions of the ThermoLink® RNA Mini Kit.

The primer sequences were forward primer: 5-ATGCATTTTTGGTTCCTATCCA-3 and backward primer: 5-TTGAATCTCATACATTTTCACATT-3.

As a template, the extracted RNA was used to amplify the esterase gene. This amplification was carried out according to the protocol of the Quant One Step RT-PCR kit (KR113). The PCR products were electrophoresed on 0.8% agarose. The PCR product was recovered, purified and sequenced.

Reconstruction of the Expression Plasmid and Transformation

The sequence containing the α-factor sequence and the coding sequence of esterase was synthesized. The synthesized sequence and the extracted plasmid pYES2 were digested with restriction enzyme HindIII and NotI. The digested gene sequence encoding esterase and vector were recovered and ligated overnight at 16 °C with T4 ligase. The constructed plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α to obtain a subcloned strain.

Plasmid Extraction and Transformation

The subcloned strain was cultured in LB medium supplied with 100 µg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C for 18 h. The single colonies were picked out and inoculated into a 50 mL flask containing 5.0 mL of YPD medium. After culturing overnight at 30 °C and 200 r/m, the cell cultures were centrifuged at 1500g for 5 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended with 50 mL of ice-cold sterilized water. The constructed plasmid was extracted.

The constructed plasmid was linearized. 20 μg of linearized DNA was dissolved in 10.0 μL TE solution. The solution was mixed with 80 μL of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells and transferred into a cold electric conversion cup. The transformation was carried out by the BTX electroporator ECM 830. After the electronic transformation, 1.0 mL of 1 M ice-cold sorbitol solution was mixed with the cells and transfer to 1.5 mL EP tube. The suspension was coated on an SD-uracil medium plate. A single colony was picked out and inoculated into YPD medium. Galactose was supplied into YPD medium to a final concentration of 10 g/L. After culture for 36.0 h, the samples were taken out to be centrifuged at 5000 r/m. The supernatant was collected. The activity of esterase in the supernatant was analyzed. The strain with the fusel esterase activity was regarded as the constructed strain.

Preparation of Esterase Solution

Candida parapsilosis strain was preincubated in 2216E medium at 28 °C, 200 r/m for 18.0 h. The strain was inoculated into the enzyme-producing medium with 2% inoculum. After incubation at 28 °C for 3 days, the fermentation broth was filtered through three layers of clean gauzes. The filtrate was centrifuged at 5000 r/m for 5.0 min to remove fine bran residue. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon filter membrane to remove the cells. The filtrate solution was used as esterase solution from the original strain.

The constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiae was transferred to YPD liquid medium and cultured for 48 h. After cultivation for 20 h, 20 g/L galactose was added into YPD liquid medium. After induction cultivation for 48 h, the fermentation broth was centrifuged at 5000g for 5.0 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon filter membrane to remove the cells. The filtrate solution was used as the esterase solution from the constructed strain.

The esterase solution was filtered using a membrane filter with a 0.45 μm pore diameter and concentrated by ultrafiltration using 10.0 kDa amico regeneration cellulose filters (Millipore, Bedford). Concentrated esterase was lyophilized into the esterase powder. 8.0 mg of the esterase powder was added into 1.0 mL of the balance buffer (20 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 7.0) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 1.0 min. The supernatant was loaded into a DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow column, which was equilibrated with the balance buffer. The esterase was eluted using the balance buffer with the NaCl concentration gradient (0.02, 0.04, 0.10, 0.14 and 1.00 mol/L). The flow rate was set at 0.6 mL/min and the collected protein fractions were measured with a spectrophotometry. The fraction with the maximum esterase activities was concentrated by ultrafiltration. The concentrated esterase solution was mixed with Loading Buffer and boiled for 5.0 min. After centrifuged at 10,000 r/m for 2.0 min at room temperature, the solution was recovered and performed SDS-PAGE.

Preparation of Fusel Oil Esterification System

The n-propanol, isobutanol, isoamyl alcohol were used as the substrates of the esterase. n-propanol 1%, isobutanol 1%, isoamyl alcohol 1%, acetic acid content 2%, esterase solution 50%, sterilized distilled water 45% were mixed as the reaction mixture. The pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 3.5 with 200 g/L NaOH solution. In the control sample, the esterase solution was replaced with an equal amount of deionized water. The esterification system was esterified at 30 °C, 200 r/m for 24 h.

Measurement of Fusel Oil Esterase Activity

The content of the fusel oil ester synthesized by the esterase was measured by headspace gas chromatography. The detection method was the following: column: 50 m capillary gas chromatography column, column temperature: two-stage temperature rise, initial temperature 35 °C, hold for 7 min, rise to 60 °C at 4 °C/min, then rise to 105 °C at 6 °C/min. Finally, rise to 200 °C at 20 °C/min for 10 min, inlet temperature 200 °C, detector temperature 220 °C, carrier gas: high purity nitrogen, hydrogen: 30.0 mL/min; air: 200 mL/min; Pre-column pressure: 30 kPa, column flow: 1.36 mL/min; tail blow: 30.0 mL/min; split ratio: 40:1; injection volume: 1 mL; internal standard: 2% n-amyl acetate.

Results

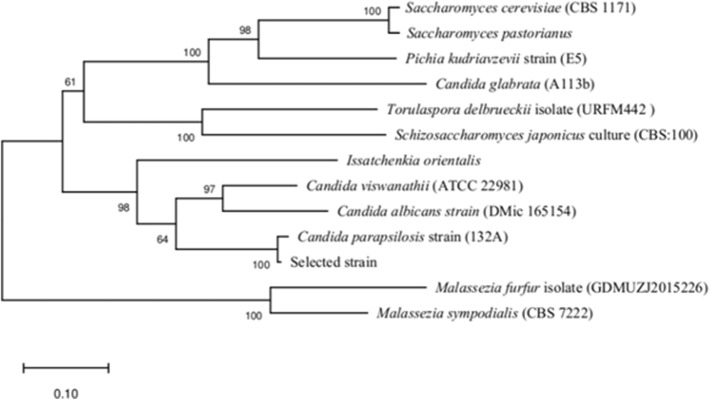

Phylogenetic Tree of Candida parapsilosis

Based on fusel oil esterase activity, a most active fungus was selected and identified using ITS region sequencing. The most similar ITS sequences were selected to construct the neighbour-joining tree. The neighbour-joining tree showed that it was mostly similar to Candida parapsilosis (Fig. 1). Candida parapsilosis, a kind of yeast, could produce carbonyl reductase [22] and proteinase [23].

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Candida parapsilosis

The lipases from Candida parapsilosis have been reported [24]. The lipase was a kind of hydrolase, which was not useful for the flavor esters synthesis. The esterase which oxidises alcohol into the esters was valuable for the flavor esters synthesis. The esterase from Candida parapsilosis could transform n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol into n-propanyl acetate, isobutanyl acetate and isoamyl acetate. The synthesizing esters characteristics of the esterase from Candida parapsilosis has not been reported.

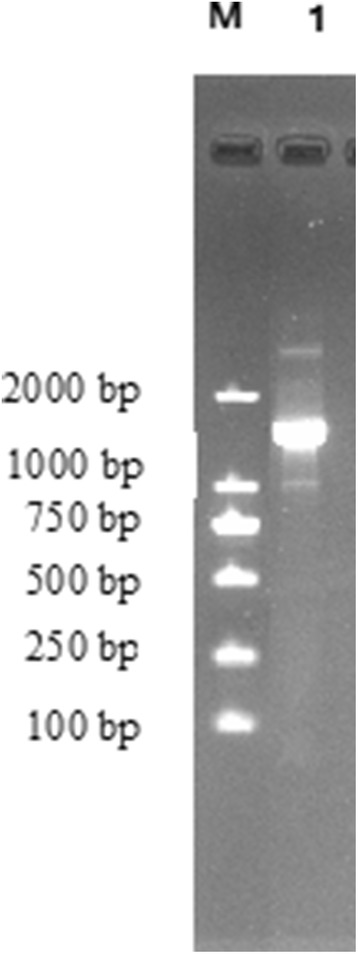

Amplification and Sequencing of Fusel Oil Esterase

The RT-PCR product of the esterase was about 1500 bp (Fig. 2). The amino acid sequence of n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol esterase was translated according to the encoding sequence. The nucleotide sequence was submitted to GenBank and was given an accession number, MN877943. The esterase from Candida parapsilosis could convense n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol into the correspondent esters. This will be significant to apply in food industry.

Fig. 2.

Electrophoresis of PCR product of n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol esterase. M, DNA marker; 1, RT-PCR product of the esterase

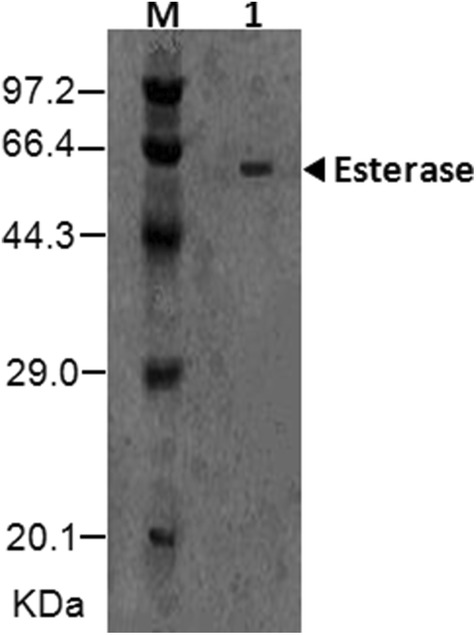

The Esterase Expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

After the induction cultivation, the culture broth was centrifuged. The supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3). According to the analysis of protein electropherogram, the constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressed the exogenous protein, which was about 50 kDa (Fig. 3). In this study, the esterase was presented a 50.86 kDa molecular weight. Previously some kinds of the esterases were expressed in Pichia pastoris [25, 26]. Pichia pastoris uses methanol as a carbon source. Methanol causes some food security problem. Saccharomyces cerevisiae can use glucose as a carbon source, which could not bring food safety problem. It was a better host strain to express the esterase compared to Pichia pastoris. Saccharomyces cerevisiae was an efficient host strain for the exogenous protein expression [27, 28]. The results indicated that the esterase has been efficiently transcribed, translated and transported out from the constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Fig. 3.

SDS-PAGE of the esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. M, Protein marker; 1, Esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Flavor Esters Synthesis with the Expressed Esterase

The catalysis ability of the esterase produced by the constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiaes was analyzed. The n-propanyl, isobutanyl and isoamyl alcohol were used as the substrates. N-propanyl was esterified into n-propanyl acetate. Isobutanyl was esterified into isobutanyl acetate. Isoamyl was esterified into isoamyl acetate. After esterification by the esterase from the constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the production of n-propanyl acetate, isobutanyl acetate and isoamyl acetate was 24.6 mg/100 mL, 8.3 mg/100 mL, 5.6 mg/100 mL, respectively. The production of n-propanyl acetate, isobutanyl acetate and isoamyl acetate synthesized by the esterase from the constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiae was higher than that synthesized by the esterase from the original strain (Table 1). The smaller the molecular weight of the substrates was, the higher concentration of the synthesized esters was. Esterase were usually hydrolysis enzymes [29–31]. The catalysis properties of the esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae were different from the common esterases. The esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed the catalysis ability of esters synthesis. The esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae had a appropriate specificity to synthesize flavor ester. All of n-propanyl acetate, isobutanyl acetate and isoamyl acetate could be the substrates of the expressed esterase.

Table 1.

Catalysis property of esterase from the constructed Saccharomyces cerevisiae

| Ester | Ester production synthesized by the esterase (mg/100 mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| Esterase from the original strain | Esterase from the constructed strain | |

| N-propyl acetate | 5.5 | 24.6 |

| Isobutyl acetate | 2.8 | 8.3 |

| Isoamyl acetate | 1.1 | 5.6 |

Discussion

In this paper, the gene encoded esterase of Candida parapsilosis was efficiently expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Despite of lipase, a hydrolase, from Candida parapsilosis was described previously [24], the esterase from Candida parapsilosis, a synthetase, has not been reported to synthesize three kinds of flavor esters. The esterase activities were detected after secretory expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The expressed esterase could esterify n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol into n-propyl acetate, isobutyl acetate and isoamyl acetate. Both of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida parapsilosis belongs to a yeast family, so the transcription, translation and protein modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae were probably similar to that in Candida parapsilosis. The similarity proved an efficient heterologous expression of the esterase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The esterase from Candida parapsilosis could synthesized 15.5 mg/100 mL n-propyl acetate, 8.7 mg/100 mL isobutyl acetate and 3.0 mg/100 mL isoamyl acetate. The esterase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae could synthesize 24.6 mg/100 mL n-propyl acetate, 8.3 mg/100 mL isobutyl acetate, 5.6 mg/100 mL isoamyl acetate. n-propyl acetate synthesized or isoamyl acetate by the esterase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was 1.59 folds or 1.87 folds higher than that synthesized by the esterase from Candida parapsilosis. The expressed esterase was valuable for biochemical synthesis of the flavor esters. The function of esterification indicated that the genome of the marine Candida parapsilosis will be probably different to those of the reported Candida parapsilosis.

Most of the reported esterases had a cap domain and a core domain. The substrate specificity was mostly affected by the cap structure. The cap domain usually shields the catalytic triad, thus contributing directly to substrate binding [31]. The esterase from Candida parapsilosis probably had the “cap” domain. The “cap” domain of the esterase from Candida parapsilosis could be a suitable entrance for n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol to go through to the active sites. In the active sites, the esterase from Candida parapsilosis convert n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol into the correspondent esters. The esterase from Candida rugosa and Candida antarctica beared the GGG(A)X-motif. The GGG(A)X-motif was crucial to the esterase activity [32]. The esterase from Candida parapsilosis had probably the GGG(A)X-motif to esterify the n-propanol, isobutanol and isoamyl alcohol.

The higher the purities of the esterase were, the higher the production of the three kinds of the flavor esters should be. Optimization of esterase producing medium or cultivation conditions such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen probably increased the esterase concentration or purities. Optimum synthesis conditions of the esterase could be obtained to improve the flavor esters production.

The catalytic characteristic of the expressed esterase was propitious to simutaneously synthesize three kinds of the flavor esters. Furthermore, the catalysis of the esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae was in aqueous system. While most of esterase catalysis was in organic system. The esterase expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae had advantages in editable security, production cost and environment protection. The functions of esterifications made it a remarkable catalyst for the application in food industry.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Foundation of Hubei Provincial Department of Education (B2018040) and Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Hubei University of Technology (No. BSQD14018).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sun JC, Yu B, Curran P, Liu SQ. Lipase-catalysed transesterification of coconut oil with fusel alcohols in a solvent-free system. Food Chem. 2012;134:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishna SH, Divakar S, Prapulla SG, Karanth NG. Enzymatic synthesis of isoamyl acetate using immobilized lipase from Rhizomucor miehei. J Biotechnol. 2001;87:193–201. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00432-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langrand G, Rondot N, Triantaphylides C, Baratti J. Short chain flavour esters synthesis by microbial lipases. Biotechnol Lett. 1990;12:581–586. doi: 10.1007/bf01030756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero MD, Calvo L, Alba C, Habulin M, Primozic M, Knez Ž. Enzymatic synthesis of isoamyl acetate with immobilized Candida antarctica lipase in supercritical carbon dioxide. J Supercrit Fluids. 2005;33:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8446(04)00114-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhetras N, Patil S, Gokhale D. Lipase of Aspergillus niger NCIM 1207: a potential biocatalyst for synthesis of isoamyl acetate. Indian J Microbiol. 2010;50:432–437. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patidar P, Mahajani SM. Esterification of fusel oil using reactive distillation—part I: reaction kinetics. Chem Eng J. 2012;207–208:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.06.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucuk Z, Ceylan K. Potential utilization of fusel oil: a kinetic approach for production of fusel oil esters through chemical reaction. Turk J Chem. 1998;22:289–300. doi: 10.1023/A:1019138718283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surburg H, Panten J. Common fragrance and flavor materials: preparation, properties and uses. 6. New York: John Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akacha NB, Gargouri M. Microbial and enzymatic technologies used for the production of natural aroma compounds: synthesis, recovery modeling, and bioprocesses. Food Bioprod Process. 2015;94:675–706. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2014.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stergiou PY, Foukis A, Filippou M, Koukouritaki M, Parapouli M, Theodorou LG, Hatziloukas E, Afendra AM, Pandey A, Papamichael E. Advances in lipase-catalyzed esterification reactions. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:1846–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajendran A, Palanisamy A, Thangavelu V. Lipase catalyzed ester synthesis for food processing industries. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2009;52:207–219. doi: 10.1590/S1516-89132009000100026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi J, Han S, Kim H. Industrial applications of enzyme biocatalysis: current status and future aspects. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:1443–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar MBA, Gao Y, Shen W, He LZ. Valorisation of protein waste: an enzymatic approach to make commodity chemicals. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2015;9:295–307. doi: 10.1007/s11705-015-1532-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen KQ, Cheng DG, Peng C, Wang D, Zhang JT. Green catalytic engineering: a powerful tool for sustainable development in chemical industry. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2018;12:835–837. doi: 10.1007/s11705-018-1756-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sebastián T, Baigori MD, Swathy SL, Pandey A, Castro GR. Enzymatic synthesis of banana flavour (isoamyl acetate) by Bacillus licheniformis S-86 esterase. Food Res Int. 2009;42:454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2008.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shakiba MH, Ali MS, Rahman RN. Cloning, expression and characterization of a novel cold adapted GDSL family esterase from Photobacterium sp. strain J15. Extremophiles. 2016;20:44–55. doi: 10.1007/s00792-015-0796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contesini FJ, Lopes DB, Macedo GA, Nascimento MG, Carvalho PO. Aspergillus sp lipase: potential biocatalyst for industrial use. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2010;67:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendes AA, Oliveira PC, Castro HF. Properties and biotechnological applications of porcine pancreatic lipase. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2012;78:119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranjan R, Yadav M, Suneja G, Harma R. Discovery of a diverse set of esterases from hot spring microbial mat and sea sediment metagenomes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;119:572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evolut. 2018;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grosch JH, Loderer C, Jestel T, Marion AS, Antje CS. Carbonyl reductase of Candida parapsilosis-stability analysis and stabilization strategy. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2015;112:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2014.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiří D, Jiří B, Olga HH, Irena S, Pavlína Ř. The crystal structure of the secreted aspartic protease 1 from Candida parapsilosis in complex with pepstatin A. J Struct Biol. 2009;167:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subileau M, Jan A-H, Nozac’h H, Pérez-Gordo M, Perrier V, Dubreucq E. The 3D model of the lipase/acyltransferase from Candida parapsilosis, a tool for the elucidation of structural determinants in CAL-A lipase superfamily. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1854;10:1400–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Waele S, Vandenberghe I, Laukens B, Planckaert S, Verweire S, Van Bogaert INA, Soetaert W, Devreese B, Ciesielska K. Optimized expression of the Starmerella bombicola lactone esterase in Pichia pastoris through temperature adaptation, codon-optimization and co-expression with HAC1. Protein Expr Purif. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng Y, Yin X, Wu MC, Yu T, Feng F, Zhu TD, Pang QF. Expression of a novel feruloyl esterase from Aspergillus oryzae in Pichia pastoris with esterification activity. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2014;110:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bond CM, Tang Y. Engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of simvastatin. Metab Eng. 2019;51:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iimura Y, Sonoki T, Habe H. Heterologous expression of Trametes versicolor laccase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr Purif. 2018;141:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldridge WN. The esterases: perspectives and problems. Chem Biol Interact. 1993;87:5–13. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(93)90019-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bornscheuer UT. Microbial carboxyl esterases: classification, properties and application in biocatalysis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2002;26:73–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romano D, Bonomi F, Mattos MC, Fonseca TS, Oliveira MCF, Molinari F. Esterases as stereoselective biocatalysts. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:547–565. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henke E, Bornscheuer UT, Schmid RD, Pleiss J. A molecular mechanism of enantiorecognition of tertiary alcohols by carboxylesterases. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:485–493. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200200518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]