Abstract

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have shown efficacy in reducing the risk of ESRD. However, patients vary in their response to RAAS blockades, and the pharmacodynamic responses to SGLT2 inhibitors decline with increasing severity of renal impairment. Thus, effective therapy for DKD is yet unmet. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), expressed by nearly all kidney cell types and infiltrating leukocytes and macrophages, is a pleiotropic cytokine involved in angiogenesis, immunomodulation, and extracellular matrix (ECM) formation. An overactive TGF-β1 signaling pathway has been implicated as a critical profibrotic factor in the progression of chronic kidney disease in human DKD. In animal studies, TGF-β1 neutralizing antibodies and TGF-β1 signaling inhibitors were effective in ameliorating renal fibrosis in DKD. Conversely, a clinical study of TGF-β1 neutralizing antibodies failed to demonstrate renal efficacy in DKD. However, overexpression of latent TGF-β1 led to anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrosis effects in non-DKD. This evidence implied that complete blocking of TGF-β1 signaling abolished its multiple physiological functions, which are highly associated with undesirable adverse events. Ideal strategies for DKD therapy would be either specific and selective inhibition of the profibrotic-related TGF-β1 pathway or blocking conversion of latent TGF-β1 to active TGF-β1.

Keywords: diabetic kidney disease, transforming growth factor-β1, fibrosis, inflammation, Smad signaling

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), the most common cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide, accounts for about 40% of new cases of ESRD each year in the United States and China (Zhang et al., 2016; Alicic et al., 2017). With the increasing incidence of diabetes, there is a heightened need for therapy to delay progression of DKD. Existing therapies have had limited success. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, such as losartan and irbesartan, have been effective in reducing the risk of ESRD for patients with DKD (Brenner et al., 2001; Lewis et al., 2001; Parving et al., 2001). However, patients exhibited great variation in their responses to RAAS blockades. In the past two decades, there has been a decline in the rate of acute myocardial infarction and death from hyperglycemic crisis, but no change has occurred in the rate of ESRD (Gregg et al., 2014). Although sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have conferred cardiovascular and renal protection (Perkovic et al., 2019), effective therapy for DKD is still unavailable. An epidemiological study revealed that the 5-year mortality rate of DKD was approximately 40%, as high as many cancers (Abdel Aziz et al., 2017). Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) signaling contributes to DKD progression, and inhibiting TGF-β1 signaling has shown potential renoprotective properties in animal and human studies. In this mini-review, we discuss the pleiotropic and the potential therapeutic effects of TGF-β1 in DKD.

Tgf-β1 and Tgf-β1 Signaling Pathway

TGF-βs exist as five isoforms, but only TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 are present in mammals; the three isoforms elicit similar responses in vitro. TGF-β1, the most abundant isoform, is synthesized by all types of resident renal cells and infiltrating inflammatory cells (Aihara et al., 2010). TGF-β1 is secreted into the extracellular matrix (ECM) in an inactive complex (latent TGF-β1) with TGF-β-latency-associated peptide (LAP) and latent TGF-β binding proteins (LTBP) (Munger et al., 1997). The activation of latent TGF-β1 is mediated by proteolytic cleavage in the presence of the serine protease plasmin, reactive oxygen species (ROS), thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), or integrins (Khalil, 1999; Kim et al., 2018). Integrins bind to the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid sequence in LAP. This binding appears to change the conformation of the latent TGF-β1 complex by tractional force (Munger et al., 1999). This conformational change presents the latent TGF-β1 complex to transmembrane metalloproteinases, such as membrane-type-1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT-1-MMP), which cleave the latent TGF-β1 complex and release active TGF-β1 (Mu et al., 2002; Sheppard, 2004; Araya et al., 2006; Wipff and Hinz, 2008). Active TGF-β1 interacts with its receptors to activate Smad-dependent and Smad-independent downstream signaling (Lan, 2011; Sutariya et al., 2016).

Smad-Dependent Signaling Pathway

Active TGF-β1 binds to a Type II membrane receptor, TGF-β Type II receptor (TβRII). This binding results in the phosphorylation and recruitment of the TGF-β Type I receptor (TβRI). The activated complex of TGF-β1-TβRI-TβRII phosphorylates Smad2 and -3. Then, the phosphorylated Smad2 and -3 bind to Smad4 to form the Smad complex (Lan, 2011). This Smad complex translocates into the nucleus and binds to Smad-binding elements (SBEs) or Smads-containing complexes (Nakao et al., 1997b; Meng et al., 2013), in turn, regulating transcription of genes encoding, e.g., collagen, fibronectin, α-smooth muscle actin (Chakravarthy et al., 2018), and Smad7 (Yan et al., 2009).

Smad proteins are classified into three subgroups. Smad2 and -3 comprise the receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads) for TGF-β1 signaling, and Smad1, -5, and -8 for bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling. Smad2 and -3 are key downstream mediators of TGF-β1, and they are highly activated in animal renal tissues in DKD (Isono et al., 2002; Høj Thomsen et al., 2017). Smad2 and -3 may have distinct functions in renal fibrosis. Either a Smad3 knockout or a Smad3-specific inhibitor delayed de-differentiation of proximal tubular cells and alleviated renal fibrosis in a streptozotocin-induced model of diabetes (Fujimoto et al., 2003; Li et al., 2010). These findings suggested that TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling has critical activities in renal fibrosis. Conversely, unlike Smad3, the function of Smad2 in DKD is unclear. Overexpression of Smad2 attenuated TGF-β1-induced phosphorylated Smad3 and collagen expression, whereas deletion of Smad2 promoted renal fibrosis via substantially enhanced Smad3 signaling (Meng et al., 2010; Loeffler et al., 2018). Although Smad2 interacts with Smad3 physically, Smad2 and -3 may compete for phosphorylation in response to TGF-β1 stimulation. Thus, Smad2 may competitively inhibit phosphorylation of Smad3 in response to TGF-β1 (Meng et al., 2010). Besides TGF-β1 signaling, Smad2 nuclear translocation and phosphorylation can also be mediated by advanced glycation end-products in DKD (Li et al., 2004). Thus, the activity of Smad2 is complicated in DKD.

The second Smad subgroup is the common-partner Smad (co-Smad), Smad4, which forms a heterotrimeric complex with phosphorylated R-Smads. The Smad4-containing complex translocates into the nucleus and regulates expression of the genes indicated earlier. Furthermore, Smad4 is implicated in suppressing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-driven inflammation by inducing Smad7 expression (Ka et al., 2012).

The third Smad subgroup is the inhibitory Smads (I-Smads). Members of this Smad family have a conserved carboxy-terminal MH2 domain. I-Smads inhibit TGF-β1 family signaling via interaction with type I receptors, and I-Smads compete with R-Smads for receptor activation (Miyazawa and Miyazono, 2017). Smad7, one of the most investigated I-Smad in DKD, can cause degradation of TβRI and Smads activity in a negative feedback process. Smad7 inhibits Smad2/3 during renal fibrosis. In chronic kidney disease, TGF-β1 signaling upregulated the Smurfs and caused ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Smad7, which led to a decrease in Smad7 protein level (Kavsak et al., 2000; Ebisawa et al., 2001; Fukasawa et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2008). Smad7 knockout mice progressed to more severe interstitial fibrosis and enhanced inflammation (Cheng et al., 2013; Chung et al., 2013), and overexpression of Smad7 in kidney was effective in reducing collagen matrix expression and in alleviating inflammatory infiltration in DKD (Ka et al., 2012). These findings revealed anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory functions of Smad7 in DKD.

Smad-Independent Signaling Pathway

In addition to Smad-mediated transcription, TGF-β1 directly activates other signal transduction pathways in the pathophysiology of kidney disease. These other pathways include the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway (Meng, 2019), growth and survival kinases phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt (Lu et al., 2019), small GTP-binding proteins such as Ras, RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, the Notch signaling pathway (Atfi et al., 1997; Sweetwyne et al., 2015), Integrin-linked kinase (ILK), and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Xu et al., 2017; Zhang and Huang, 2018). These non-canonical, non-Smad pathways can indirectly participate in de-differentiation of proximal tubular cells (Lu et al., 2019), apoptosis (Matoba et al., 2017), and matrix formation (Meng, 2019), thereby mediating signaling responses either as stand-alone pathways or as pathways that converge onto Smads to control Smad activities.

Tgf-β1 Promotes Renal Fibrosis in DKD

Diabetic kidney disease pathology is characterized by thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, mesangial expansion, segmental glomerulosclerosis or global glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and afferent and efferent arteriole hyalinosis (Najafian et al., 2015). The TGF-β1 signaling pathway is activated in DKD, and the inhibition of TGF-β1 attenuates fibrosis in animal models of diabetes (Meng, 2019). Pathogenic stimuli in DKD activate TGF-β1 signaling. Angiotensin-II, which was elevated in mesangial cells and glomerular endothelial cells, has been implicated in activating TGF-β1 by generation of ROS from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (Lee, 2011; Morales et al., 2012) or by activating protein kinase C- and p38 MAPK-dependent pathways (Weigert et al., 2002). Hyperglycemia, mechanical stretch, and advanced glycation end products were found to upregulate TGF-β1 in DKD (Gruden et al., 2000; Chuang et al., 2015). TSP-1, a prototypic matricellular ECM protein, was heavily deposited in glomeruli of patients with DKD (Hohenstein et al., 2008). TSP-1 binds to the latent TGF-β1 complex, and, by a non-proteolytic mechanism, converts latent TGF-β1 to the active form, which leads to upregulation of TGF-β1 signaling (Murphy-Ullrich and Suto, 2018). Direct evidence for the importance of TSP-1 in regulating TGF-β signaling in DKD comes from two different models of type 1 diabetes. Streptozotocin-treated TSP-1 knockout mice showed decreased glomerular TGF-β signaling as measured by phosphorylated Smad2, and attenuated glomerulosclerosis (Daniel et al., 2007). In another type 1 diabetic animal model, uninephrectomized Akita mice treated with TSP-1 blocking peptide LSKL were protected from tubulointerstitial fibrosis and had reduced phosphorylation of Smad2 and -3 (Lu et al., 2011).

Mechanisms of TGF-β1 regulated fibrosis in DKD are multifactorial and involve (1) overexpression of ECM, (2) decreased degradation of ECM, (3) enhanced cross-linking between collagen and elastin fibers, and (4) overactivation of proximal tubular and endothelial cell de-differentiation. Both canonical TGF-β1/Smads-dependent signaling pathways and alternative signaling by TGF-β1 are involved in stimulating collagen expression and accumulation. Neutralizing all three mammalian TGF-β isoforms (-β1, -β2, and -β3) with antibodies reduced ECM gene (fibronectin and type IV collagen) expression and attenuated renal fibrosis in mice with type 1 or type 2 diabetes (Sharma et al., 1996; Ziyadeh et al., 2000). Thus, TGF-β1 has a critical signaling function in ECM accumulation in DKD.

TGF-β1 expression greatly inhibited ECM degradation by promoting the synthesis of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) which resulted in renal fibrosis (Shihab et al., 1997). The abundance of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), an ECM-degradation MMP, was decreased in transgenic mice that overexpressed TGF-β1 (Zechel et al., 2002; Ueberham et al., 2003). In addition, TGF-β1 augmented the expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (Ueberham et al., 2003; Abdel Aziz et al., 2017), which inhibited the ECM-degrading MMPs.

TGF-β1 promotes formation of the cross-linking between collagen and elastin fibers by upregulating lysyl oxidase (Boak et al., 1994; Di Donato et al., 1997). In vitro, TGF-β1 significantly increased (∼5 times) lysyl oxidase expression in tubular epithelial cells (Di Donato et al., 1997). In addition, TGF-β1 stimulated expression of procollagen lysyl hydroxylase 2, an enzyme that hydroxylates lysyl residues of collagen telopeptides and stabilizes collagen cross-linking (Gjaltema et al., 2015). Crosslinking increases ECM resistance to degradation by MMPs (El Hajj et al., 2018).

De-differentiation of the proximal tubular cells and endothelial cells contributes to renal fibrosis in diabetic mice. Extensive studies confirmed that TGF-β1 contributes to renal fibrosis by stimulating proximal tubular de-differentiation (Zeisberg et al., 2003) and endothelial de-differentiation (Li et al., 2009; Pardali et al., 2017). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) accumulated in DKD and HIF-1α enhanced de-differentiation of murine proximal tubular epithelial cells in vitro (Higgins et al., 2007). Conditional HIF-1α ablation decreased interstitial collagen deposition and inhibited the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis (Higgins et al., 2007). Although TGF-β1 stimulation increased HIF-1α expression, blocking TGF-β1 signaling inhibited HIF-1α activity, and, conversely, blocking HIF-1α activity decreased TGF-β1 signaling (Basu et al., 2011). These studies suggested cross-talk between TGF-β1 and HIF-1α signaling in regulating proximal tubular de-differentiation (Basu et al., 2011). As to endothelial de-differentiation, in animal models of folic acid nephropathy or unilateral ureteral obstruction, curtailed TGF-β signaling in the endothelium by endothelium-specific heterozygous TβRII knockout reduced endothelial de-differentiation and led to less tubulointerstitial fibrosis (Xavier et al., 2015). The mechanism by which TGF-β1 regulates endothelial de-differentiation is unknown. TGF-β1 stimulated endothelial de-differentiation in mouse endothelial cells by activating Snail expression (Kokudo et al., 2008).

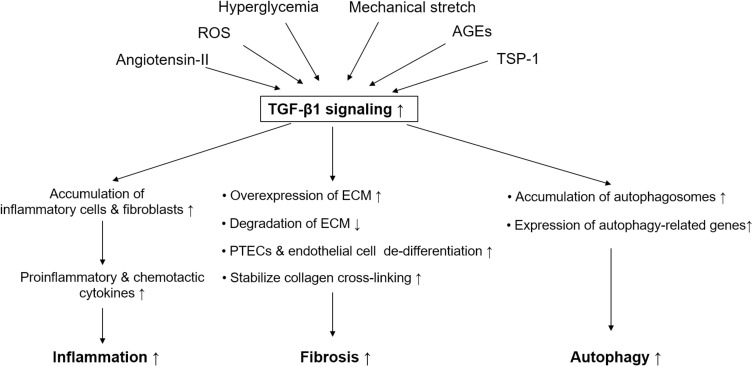

In summary, the active TGF-β1 system promotes renal fibrosis, and it is involved in elevating collagen synthesis, suppressing ECM degradation, promoting collagen cross-linking, and fostering proximal tubular or endothelial cell de-differentiation (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Simplified schematic diagram of pathological role of TGF-β1 signaling in diabetic kidney disease. Pathogenic stimuli in diabetic kidney disease like hyperglycemia, angiotensin-II, reactive oxygen species, mechanical stretch, advanced glycation end products, and thrombospondin-1 are able to active TGF-β1 signaling. TGF-β1 signaling plays an important role in mediating renal fibrosis, inflammation, and autophagy in proximal tubular epithelial cells in diabetic kidney disease. TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PTECs, proximal tubular epithelial cells; AGE, advanced glycation end products; TSP-1, thrombospondin-1; ECM, extracellular matrix.

Diverse Inflammatory Functions of Tgf-β1 in DKD

TGF-β1 is a critical factor in the pathophysiological progression of DKD, having both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties (Sureshbabu et al., 2016).

TGF-β1 control of innate immune cells can have severe pathological consequences. Leukocytes and fibroblasts are recruited by the activation of resident kidney immune cells in DKD. This recruitment stimulates the expression of pro-inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines, which further drives the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages (Lv et al., 2018). TGF-β1 recruited macrophages and dendritic cells by stimulating the production of chemokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Furthermore, the secreted chemokines induced TGF-β1 expression in a positive feedback loop (Cheng et al., 2005), which sustained the high levels of TGF-β1 in the microenvironment. TGF-β1 induced the expression and release of other proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-8 (IL-8) and MCP-1 (Qi et al., 2006) in proximal tubular cells. In addition, TGF-β1 drove the differentiation of T helper 17 cells, which were activated in various proinflammatory conditions. In the presence of IL-6, TGF-β1 promoted the differentiation of naive T lymphocytes into proinflammatory T helper cells that produced IL-17 and augmented autoimmune conditions, which were enhanced by IL-1β and TNF-α (Korn et al., 2009; Sanjabi et al., 2009). In this way, TGF-β1 propagates and amplifies the proinflammatory and profibrotic processes that contribute to renal insufficiency in DKD (Figure 1).

Nevertheless, TGF-β1 also possesses anti-inflammatory properties, which was suggested by the findings that targeted deletion of the TGF-β1 gene resulted in profound multifocal inflammatory disease in mice (Shull et al., 1992). Additionally, TGF-β1 knockout mice developed severe inflammatory responses that were evidenced by massive lymphocytes, macrophages, immunoblasts, and plasma cell infiltration in many organs (Kulkarni et al., 1993). Tubular epithelial cell-specific TβRII knockout mice showed massive leukocytes or macrophages infiltration, increased proinflammatory cytokine release, and enhanced renal inflammation (Meng et al., 2012). Direct evidence for the importance of TGF-β1 in anti-inflammation comes from two studies. First, Ma et al. (2004) used animal studies to investigate the effect of different doses of TGF-β antibodies on glomerulosclerosis. Only low dose TGF-β antibody decreased macrophage infiltration, and reduced sclerosis, indicating that the amount of TGF-β may influence the inflammatory process. Second, regulatory T cells appeared to ameliorate DKD, and nude mice, which lacked all T-cell subtypes, had more severe DKD (Lim et al., 2010; Eller et al., 2011). In the presence of IL-2, TGF-β1 converted naive T cells into Foxp3 + regulatory T cells and inhibited the progression of DKD (Davidson et al., 2007; Kanamori et al., 2016).

Thus, the effects of TGF-β1 activation in renal inflammation may be protective or harmful depending on concentration or the presence of IL-6. However, the underlying mechanism by which TGF-β1 exerts its anti-inflammatory properties in DKD requires further investigation.

Other Activities of Tgf-β1 in DKD

Recent studies illustrated that TGF-β1 promoted autophagy (Ding et al., 2010; Koesters et al., 2010). Autophagy, a system for removing protein aggregates and damaged organelles to maintain cellular homeostasis, is impaired in glomeruli and tubules in DKD (Yang et al., 2018). However, persistent activation of autophagy in kidney tubular epithelial cells induced tubular degeneration and promoted renal fibrosis (Livingston et al., 2016). Overexpression of TGF-β1 in renal tubules induced the accumulation of autophagosomes and stimulated expression of autophagy-related genes (Koesters et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2012). In proximal tubular cells, TGF-β1 promoted autophagy by generation of ROS, which contributed to the proapoptotic effect of TGF-β1 (Xu et al., 2012). Koesters et al. (2010) proposed TGF-β1-driven autophagy as a novel mechanism of tubular degeneration that led to renal interstitial fibrosis. On the contrary, TGF-β1 induced autophagy had positive effects. In a study by Ding et al. (2010), TGF-β1 induced autophagy in mesangial cells, and autophagy enhanced cell survival by preventing mesangial cells from undergoing apoptosis. Whether TGF-β1 driven autophagy has protective or deleterious effects on kidney depending upon the amount. In the study by Koesters et al., TGF-β1 level was higher than its level in pathological disease states, which triggered violent autophagy and promoted kidney injury. Thus, we need further clarification of the functions of TGF-β1 signaling-induced autophagy in the pathogenesis of DKD.

TGF-β1 also suppresses reabsorption of glucose by proximal epithelial cells. A dose-dependent increase in TGF-β1 expression by genetic manipulation increased urinary output of glucose in Akita mice, whereas genetic insufficiency of TGF-β1 decreased glucose output (Hathaway et al., 2015). Moreover, SGLT2 was directly regulated by TGF-β1 via Smad3 (Panchapakesan et al., 2013) and TGF-β1 showed decreased expression of SGLT1 and SGLT2 (Lee and Han, 2010). Thus, these results support the notion that TGF-β1 suppresses urinary glucose reabsorption in proximal tubular epithelial cells (Figure 1).

Tgf-β1 Signaling as a Therapeutic Strategy for DKD

Blockade of TGF-β1 signaling as a therapeutic strategy has been achieved by gene technology and pharmacological drugs (Table 1). Inhibition of TGF-β with a pan-neutralizing monoclonal antibody (1D11) against all three isoforms ameliorated renal fibrosis and alleviated kidney structural changes in the rodent models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Sharma et al., 1996; Ziyadeh et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2003; Benigni et al., 2006). Pirfenidone is a low molecular weight synthetic molecule that has antifibrotic properties in animal models; it suppresses production of ROS and downregulates genes encoding profibrotic cytokines, such as α-SMA, collagen I, and collagen IV. Pirfenidone upregulates regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (Xie et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Pourgholamhossein et al., 2018). Moreover, RamachandraRao et al. (2009) found that pirfenidone decreased TGF-β promoter activity, blocked TGF-β1 production, and was effective in reducing mesangial matrix expansion and fibrosis in DKD. Switching TGF-β1 expression from low to high by genetic manipulation exacerbated renal injury in Akita mice, a result that further supported the idea that blockade of TGF-β1 was renoprotective for DKD (Hathaway et al., 2015).

TABLE 1.

Pre-clinical and clinical studies aimed to TGF-β signaling in diabetic kidney disease.

| Authors | Target | Method | Subject | Major findings |

| Preclinical studies | ||||

| Sharma et al., 1996 | TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | Neutralizing monoclonal antibody | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Ziyadeh et al., 2000 | TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | Neutralizing monoclonal antibody | db/db mice | Decreased glomerular mesangial matrix expansion and attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Chen et al., 2003 | TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | Neutralizing monoclonal antibody | db/db mice | Reversed the glomerular basement membrane thickening and mesangial matrix expansion, attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Benigni et al., 2006 | TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3 | Neutralizing monoclonal antibody | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Alleviated sclerotic glomerulosclerosis and attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Petersen et al., 2008 | TGF-β type I and type II receptor kinase activity | GW788388, pharmacological inhibitor | db/db mice | Decreased epithelial-mesenchymal transitions and attenuated renal fibrosis |

| RamachandraRao et al., 2009 | TGF-β1 promoter activity; other pathways besides TGF-β (suppressing production of reactive oxygen species and downregulating profibrotic cytokine genes) | Pirfenidone, a pharmacological inhibitor | db/db mice | Ameliorated mesangial matrix expansion and attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Hathaway et al., 2015 | TGF-β1 | Genetic overexpression | Akita mice | Progressively exacerbated thicker glomerular basement membranes and severe podocyte effacement is dose-dependent |

| Fujimoto et al., 2003 | Smad3 | Genetic knockout | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Alleviated glomerular basement membrane thickness and attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Li et al., 2010 | Smad3 | SIS3, pharmacological inhibitor | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Ka et al., 2012 | Smad7 | Ultrasound-mediated gene transfer of inducible Smad7 overexpression plasmids | db/db mice | Inhibited diabetic kidney injury including fibrosis and inflammation |

| Loeffler et al., 2018 | Smad2 | Renal tubular, endothelial, and interstitial cells-specific knockout | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Reduced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and attenuated renal fibrosis |

| Clinical studies | ||||

| Sharma et al., 2011 | TGF-β1 promoter activity; other pathways besides TGF-β (suppressing production of reactive oxygen species and downregulating profibrotic cytokine genes) | Pirfenidone, a pharmacological inhibitor | Type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients | Increased estimated glomerular filtration rate level |

| Voelker et al., 2017 | TGF-β1 | Neutralizing monoclonal antibody added to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor | Type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients | Failed to slow the progression of diabetic kidney disease |

TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1.

The success of TGF-β1 signaling inhibition in animal studies has promoted the strategy in clinical investigations with DKD (Sharma et al., 2011; Voelker et al., 2017). Pirfenidone significantly increased estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) in a cohort of 77 diabetic patients with baseline eGFR of 20–75 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Sharma et al., 2011). However, a placebo-controlled, phase II study that used a humanized TGF-β1-specific neutralizing monoclonal antibody plus renin-angiotensin system blockades failed to slow the progression of DKD in diabetic patients who had eGFR of 20–60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (Voelker et al., 2017). Lack of improvement in clinical trials may be explained by the fact that rodent models of diabetes do not recapitulate tubulointerstitial fibrosis to the same degree observed in human disease. Also, inhibiting TGF-β1 fully and indiscriminately may not be wise because of its multiple physiological functions.

Nevertheless, targeting the conversion of latent to active TGF-β1 holds promise as a DKD therapeutic intervention. Animal studies revealed that overexpression of an active form of TGF-β1 in liver led to progressive kidney fibrosis in mice (Kopp et al., 1996), whereas overexpression of latent TGF-β1 in the skin displayed anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrosis effects in obstructive and crescentic glomerulonephritis (Huang et al., 2008a, b). The distinct functions of active and latent TGF-β1 in renal fibrosis and inflammation suggest that a better therapeutic approach would be to block conversion of latent TGF-β to active TGF-β. Wong et al. (2011) showed that inhibiting conversion of latent to active TGF-β1 in human proximal tubular cells reduced matrix protein expression and inhibited fibrosis under hyperglycemia and hypoxia conditions. What is more, the αv-containing integrins with different β-subunits that interact with latent TGF-β1 and activate TGF-β1 have a critical function in kidney fibrosis. A pharmacologic inhibitor of αvβ1 integrin prevented activation of the latent TGF-β complex and ameliorated renal fibrosis in mice fed an adenine diet (Chang et al., 2017). The mechanisms of the distinct functions of latent versus active TGF-β1 may be related to the prevention of Smad7 from Smurf-mediated ubiquitination and degradation in response to higher levels of latent TGF-β1 (Lan, 2011). Smad7 inhibits TGF-β signaling by promoting degradation of the TβRI and inhibiting Smad2/3/4 activity (Nakao et al., 1997a; Miyazawa and Miyazono, 2017). But in chronic kidney disease, active TGF-β1 activates the Smurfs and arkadia-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome pathways, which degrades Smad7 protein by a post-transcriptional modification mechanism (Kavsak et al., 2000; Ebisawa et al., 2001; Fukasawa et al., 2004).

Conclusion

On the basis of experimental and clinical studies, modulating TGF-β1, instead of directly inhibiting TGF-β1 ligands/receptors, may be a good antifibrosis tactic for DKD. TGF-β1 promotes wound healing (Wang et al., 2014), tissue regeneration (Borges et al., 2013), anti-inflammation (Kulkarni et al., 1993), autophagy (Koesters et al., 2010), and urinary glucose regulation (Hathaway et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the dose regimen must be considered carefully because a large dose of TGF-β blockade had severe toxicity and poor efficacy in animal experiments (Khanna et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2004). A pan-neutralizing monoclonal antibody could also lead to undesired effects such as tumor formation, even though animal studies have not exhibited such events during prolonged TGF-β1 inhibition. What is more, developing molecules that suppress the activation of latent TGF-β1 would be a potential therapy. Given the central role of TGF-β1 in the pathophysiology of DKD, the TGF-β1 system is an attractive target to retard the progression of DKD, provided that the approach maintains an acceptable balance between renoprotective and harmful effects.

Author Contributions

LZ and FL conceptualized this review and decided on the content. LZ, YZ, and FL wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank AiMi Academic Services for English language editing and review services.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81970626 and 81670662) and Key Research and Development Project of Sichuan Science Technology Department (Grant No. 19ZDYF1273).

References

- Abdel Aziz M. A., Badary D. M., Hussein M. R. A. (2017). Renal damage following Alloxan-induced diabetes is associated with generation of reactive oxygen species, alterations of p53, TGF-beta1, and extracellular matrix metalloproteinases in rats. Cell Biol. Int. 41 525–533. 10.1002/cbin.10752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara K., Ikeda Y., Yagi S., Akaike M., Matsumoto T. (2010). Transforming growth factor-beta1 as a common target molecule for development of cardiovascular diseases, renal insufficiency and metabolic syndrome. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2011:175381. 10.4061/2011/175381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alicic R. Z., Rooney M. T., Tuttle K. R. (2017). Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12 2032–2045. 10.2215/CJN.11491116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya J., Cambier S., Morris A., Finkbeiner W., Nishimura S. L. (2006). Integrin-mediated transforming growth factor-beta activation regulates homeostasis of the pulmonary epithelial-mesenchymal trophic unit. Am. J. Pathol. 169 405–415. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atfi A., Djelloul S., Chastre E., Davis R., Gespach C. (1997). Evidence for a role of Rho-like GTPases and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) in transforming growth factor beta-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 272 1429–1432. 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R. K., Hubchak S., Hayashida T., Runyan C. E., Schumacker P. T., Schnaper H. W. (2011). Interdependence of HIF-1alpha and TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling in normoxic and hypoxic renal epithelial cell collagen expression. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 300 F898–F905. 10.1152/ajprenal.00335.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benigni A., Zoja C., Campana M., Corna D., Sangalli F., Rottoli D., et al. (2006). Beneficial effect of TGFbeta antagonism in treating diabetic nephropathy depends on when treatment is started. Nephron Exp. Nephrol. 104 e158–e168. 10.1159/000094967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boak A. M., Roy R., Berk J., Taylor L., Polgar P., Goldstein R. H., et al. (1994). Regulation of lysyl oxidase expression in lung fibroblasts by transforming growth factor-beta 1 and prostaglandin E2. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 11 751–755. 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.6.7946403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F. T., Melo S. A., Özdemir B. C., Kato N., Revuelta I., Miller C. A., et al. (2013). TGF-β1-containing exosomes from injured epithelial cells activate fibroblasts to initiate tissue regenerative responses and fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24 385–392. 10.1681/asn.2012101031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. M., Cooper M. E., de Zeeuw D., Keane W. F., Mitch W. E., Parving H. H., et al. (2001). Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 345 861–869. 10.1056/NEJMoa011161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy A., Khan L., Bensler N. P., Bose P., De Carvalho D. D. (2018). TGF-β-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure. Nat. Commun. 9:4692. 10.1038/s41467-018-06654-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Lau W. L., Jo H., Tsujino K., Gewin L., Reed N. I., et al. (2017). Pharmacologic blockade of v1 integrin ameliorates renal failure and fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28 1998–2005. 10.1681/ASN.2015050585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Iglesias-de la Cruz M. C., Jim B., Hong S. W., Isono M., Ziyadeh F. N. (2003). Reversibility of established diabetic glomerulopathy by anti-TGF-beta antibodies in db/db mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300 16–22. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02708-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Diaz Encarnacion M. M., Warner G. M., Gray C. E., Nath K. A., Grande J. P. (2005). TGF-beta1 stimulates monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in mesangial cells through a phosphodiesterase isoenzyme 4-dependent process. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289 C959–C970. 10.1152/ajpcell.00153.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Cui T., Fu P., Liu F., Zhou L. (2013). Dyslipidemia is associated with tunneled-cuffed catheter-related central venous thrombosis in hemodialysis patients: a retrospective, multicenter study. Artif. Organs 37 E155–E161. 10.1111/aor.12086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang C.-T., Guh J.-Y., Lu C.-Y., Chen H.-C., Chuang L.-Y. (2015). S100B is required for high glucose-induced pro-fibrotic gene expression and hypertrophy in mesangial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 35 546–552. 10.3892/ijmm.2014.2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A. C., Dong Y., Yang W., Zhong X., Li R., Lan H. Y. (2013). Smad7 suppresses renal fibrosis via altering expression of TGF-β/Smad3-regulated microRNAs. Mol. Ther. 21 388–398. 10.1038/mt.2012.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel C., Schaub K., Amann K., Lawler J., Hugo C. (2007). Thrombospondin-1 is an endogenous activator of TGF-beta in experimental diabetic nephropathy in vivo. Diabetes 56 2982–2989. 10.2337/db07-0551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson T. S., DiPaolo R. J., Andersson J., Shevach E. M. (2007). Cutting Edge: IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta-mediated induction of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 178 4022–4026. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato A., Ghiggeri G. M., Di Duca M., Jivotenko E., Acinni R., Campolo J., et al. (1997). Lysyl oxidase expression and collagen cross-linking during chronic adriamycin nephropathy. Nephron 76 192–200. 10.1159/000190168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Kim J. K., Kim S. I., Na H. J., Jun S. Y., Lee S. J., et al. (2010). TGF-β1 protects against mesangial cell apoptosis via induction of autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 285 37909–37919. 10.1074/jbc.M109.093724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebisawa T., Fukuchi M., Murakami G., Chiba T., Tanaka K., Imamura T., et al. (2001). Smurf1 interacts with transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor through Smad7 and induces receptor degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 276 12477–12480. 10.1074/jbc.C100008200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hajj E. C., El Hajj M. C., Ninh V. K., Gardner J. D. (2018). Inhibitor of lysyl oxidase improves cardiac function and the collagen/MMP profile in response to volume overload. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 315 H463–H473. 10.1152/ajpheart.00086.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eller K., Kirsch A., Wolf A. M., Sopper S., Tagwerker A., Stanzl U., et al. (2011). Potential role of regulatory T cells in reversing obesity-linked insulin resistance and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 60 2954–2962. 10.2337/db11-0358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto M., Maezawa Y., Yokote K., Joh K., Kobayashi K., Kawamura H., et al. (2003). Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against streptozotocin-induced diabetic glomerulopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305 1002–1007. 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00885-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa H., Yamamoto T., Togawa A., Ohashi N., Fujigaki Y., Oda T., et al. (2004). Down-regulation of Smad7 expression by ubiquitin-dependent degradation contributes to renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 8687–8692. 10.1073/pnas.0400035101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjaltema R. A., de Rond S., Rots M. G., Bank R. A. (2015). Procollagen Lysyl Hydroxylase 2 expression is regulated by an alternative downstream transforming growth factor β-1 activation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 290 28465–28476. 10.1074/jbc.M114.634311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg E. W., Li Y., Wang J., Burrows N. R., Ali M. K., Rolka D., et al. (2014). Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990–2010. N. Engl. J. Med. 370 1514–1523. 10.1056/NEJMoa1310799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruden G., Zonca S., Hayward A., Thomas S., Maestrini S., Gnudi L., et al. (2000). Mechanical stretch-induced fibronectin and transforming growth factor-beta1 production in human mesangial cells is p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent. Diabetes 49 655–661. 10.2337/diabetes.49.4.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway C. K., Gasim A. M., Grant R., Chang A. S., Kim H. S., Madden V. J., et al. (2015). Low TGFβ1 expression prevents and high expression exacerbates diabetic nephropathy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 5815–5820. 10.1073/pnas.1504777112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D. F., Kimura K., Bernhardt W. M., Shrimanker N., Akai Y., Hohenstein B., et al. (2007). Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Invest. 117 3810–3820. 10.1172/jci30487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenstein B., Daniel C., Hausknecht B., Boehmer K., Riess R., Amann K. U., et al. (2008). Correlation of enhanced thrombospondin-1 expression, TGF-beta signalling and proteinuria in human type-2 diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 23 3880–3887. 10.1093/ndt/gfn399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høj Thomsen L., Fog-Tonnesen M., Nielsen Fink L., Norlin J., de Vinuesa A. G., Krarup Hansen T., et al. (2017). Smad2 phosphorylation in diabetic kidney tubule epithelial cells is associated with modulation of several transforming growth factor-β family members. Nephron 135 291–306. 10.1159/000453337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. R., Chung A. C., Wang X. J., Lai K. N., Lan H. Y. (2008a). Mice overexpressing latent TGF-beta1 are protected against renal fibrosis in obstructive kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295 F118–F127. 10.1152/ajprenal.00021.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. R., Chung A. C., Zhou L., Wang X. J., Lan H. Y. (2008b). Latent TGF-beta1 protects against crescentic glomerulonephritis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19 233–242. 10.1681/asn.2007040484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isono M., Chen S., Hong S. W., Iglesias-de la Cruz M. C., Ziyadeh F. N. (2002). Smad pathway is activated in the diabetic mouse kidney and Smad3 mediates TGF-beta-induced fibronectin in mesangial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296 1356–1365. 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02084-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka S. M., Yeh Y. C., Huang X. R., Chao T. K., Hung Y. J., Yu C. P., et al. (2012). Kidney-targeting Smad7 gene transfer inhibits renal TGF-β/MAD homologue (SMAD) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signalling pathways, and improves diabetic nephropathy in mice. Diabetologia 55 509–519. 10.1007/s00125-011-2364-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori M., Nakatsukasa H., Okada M., Lu Q., Yoshimura A. (2016). Induced regulatory T cells: their development, stability, and applications. Trends Immunol. 37 803–811. 10.1016/j.it.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavsak P., Rasmussen R. K., Causing C. G., Bonni S., Zhu H., Thomsen G. H., et al. (2000). Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation. Mol. Cell 6 1365–1375. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00134-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil N. (1999). TGF-beta: from latent to active. Microbes Infect 1 1255–1263. 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00259-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna A. K., Plummer M. S., Hilton G., Pieper G. M., Ledbetter S. (2004). Anti-transforming growth factor antibody at low but not high doses limits cyclosporine-mediated nephrotoxicity without altering rat cardiac allograft survival: potential of therapeutic applications. Circulation 110 3822–3829. 10.1161/01.Cir.0000150400.15354.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. K., Sheppard D., Chapman H. A. (2018). TGF-β1 signaling and tissue fibrosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10:a022293. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koesters R., Kaissling B., Lehir M., Picard N., Theilig F., Gebhardt R., et al. (2010). Tubular overexpression of transforming growth factor-beta1 induces autophagy and fibrosis but not mesenchymal transition of renal epithelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 177 632–643. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokudo T., Suzuki Y., Yoshimatsu Y., Yamazaki T., Watabe T., Miyazono K. (2008). Snail is required for TGFbeta-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition of embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 121 3317–3324. 10.1242/jcs.028282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp J. B., Factor V. M., Mozes M., Nagy P., Sanderson N., Böttinger E. P., et al. (1996). Transgenic mice with increased plasma levels of TGF-beta 1 develop progressive renal disease. Lab. Invest. 74 991–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T., Bettelli E., Oukka M., Kuchroo V. K. (2009). IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27 485–517. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A. B., Huh C. G., Becker D., Geiser A., Lyght M., Flanders K. C., et al. (1993). Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 770–774. 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan H. Y. (2011). Diverse roles of TGF-β/Smads in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 7 1056–1067. 10.7150/ijbs.7.1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. S. (2011). Pathogenic role of TGF-β in the progression of podocyte diseases. Histol. Histopathol. 26 107–116. 10.14670/hh-26.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Han H. J. (2010). Troglitazone ameliorates high glucose-induced EMT and dysfunction of SGLTs through PI3K/Akt, GSK-3β, Snail1, and β-catenin in renal proximal tubule cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 298 F1263–F1275. 10.1152/ajprenal.00475.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis E. J., Hunsicker L. G., Clarke W. R., Berl T., Pohl M. A., Lewis J. B., et al. (2001). Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 345 851–860. 10.1056/NEJMoa011303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Qu X., Bertram J. F. (2009). Endothelial-myofibroblast transition contributes to the early development of diabetic renal interstitial fibrosis in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 175 1380–1388. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Qu X., Yao J., Caruana G., Ricardo S. D., Yamamoto Y., et al. (2010). Blockade of endothelial-mesenchymal transition by a Smad3 inhibitor delays the early development of streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 59 2612–2624. 10.2337/db09-1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. H., Huang X. R., Zhu H. J., Oldfield M., Cooper M., Truong L. D., et al. (2004). Advanced glycation end products activate Smad signaling via TGF-beta-dependent and independent mechanisms: implications for diabetic renal and vascular disease. FASEB J. 18 176–178. 10.1096/fj.02-1117fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li H., Liu S., Pan P., Su X., Tan H., et al. (2018). Pirfenidone ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Mol. Immunol. 99 134–144. 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A. K. H., Ma F. Y., Nikolic-Paterson D. J., Kitching A. R., Thomas M. C., Tesch G. H. (2010). Lymphocytes promote albuminuria, but not renal dysfunction or histological damage in a mouse model of diabetic renal injury. Diabetologia 53 1772–1782. 10.1007/s00125-010-1757-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. Y., Li X. Z., Peng Y. M., Liu H., Liu Y. H. (2008). Arkadia regulates TGF-beta signaling during renal tubular epithelial to mesenchymal cell transition. Kidney Int. 73 588–594. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M. J., Ding H. F., Huang S., Hill J. A., Yin X. M., Dong Z. (2016). Persistent activation of autophagy in kidney tubular cells promotes renal interstitial fibrosis during unilateral ureteral obstruction. Autophagy 12 976–998. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1166317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler I., Liebisch M., Allert S., Kunisch E., Kinne R. W., Wolf G. (2018). FSP1-specific SMAD2 knockout in renal tubular, endothelial, and interstitial cells reduces fibrosis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in murine STZ-induced diabetic nephropathy. Cell Tissue Res. 372 115–133. 10.1007/s00441-017-2754-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A., Miao M., Schoeb T. R., Agarwal A., Murphy-Ullrich J. E. (2011). Blockade of TSP1-dependent TGF-β activity reduces renal injury and proteinuria in a murine model of diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Pathol. 178 2573–2586. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q., Wang W. W., Zhang M. Z., Ma Z. X., Qiu X. R., Shen M., et al. (2019). ROS induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the TGF-beta1/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Exp. Ther. Med. 17 835–846. 10.3892/etm.2018.7014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv W., Booz G. W., Wang Y., Fan F., Roman R. J. (2018). Inflammation and renal fibrosis: recent developments on key signaling molecules as potential therapeutic targets. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 820 65–76. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. J., Jha S., Ling H., Pozzi A., Ledbetter S., Fogo A. B. (2004). Divergent effects of low versus high dose anti-TGF-beta antibody in puromycin aminonucleoside nephropathy in rats. Kidney Int. 65 106–115. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00381.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoba K., Kawanami D., Nagai Y., Takeda Y., Akamine T., Ishizawa S., et al. (2017). Rho-kinase blockade attenuates podocyte apoptosis by inhibiting the notch signaling pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:E1795. 10.3390/ijms18081795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.-M. (2019). Inflammatory mediators and renal fibrosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1165 381–406. 10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X. M., Chung A. C., Lan H. Y. (2013). Role of the TGF-beta/BMP-7/Smad pathways in renal diseases. Clin. Sci. 124 243–254. 10.1042/CS20120252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X. M., Huang X. R., Chung A. C., Qin W., Shao X., Igarashi P., et al. (2010). Smad2 protects against TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated renal fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 21 1477–1487. 10.1681/asn.2009121244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X. M., Huang X. R., Xiao J., Chung A. C., Qin W., Chen H. Y., et al. (2012). Disruption of Smad4 impairs TGF-β/Smad3 and Smad7 transcriptional regulation during renal inflammation and fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. Kidney Int. 81 266–279. 10.1038/ki.2011.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa K., Miyazono K. (2017). Regulation of TGF-β family signaling by inhibitory smads. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9:a022095. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales M. G., Vazquez Y., Acuña M. J., Rivera J. C., Simon F., Salas J. D., et al. (2012). Angiotensin II-induced pro-fibrotic effects require p38MAPK activity and transforming growth factor beta 1 expression in skeletal muscle cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44 1993–2002. 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu D., Cambier S., Fjellbirkeland L., Baron J. L., Munger J. S., Kawakatsu H., et al. (2002). The integrin alpha(v)beta8 mediates epithelial homeostasis through MT1-MMP-dependent activation of TGF-beta1. J. Cell Biol. 157 493–507. 10.1083/jcb.200109100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger J. S., Harpel J. G., Gleizes P. E., Mazzieri R., Nunes I., Rifkin D. B. (1997). Latent transforming growth factor-beta: structural features and mechanisms of activation. Kidney Int. 51 1376–1382. 10.1038/ki.1997.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger J. S., Huang X., Kawakatsu H., Griffiths M. J., Dalton S. L., Wu J., et al. (1999). The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell 96 319–328. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich J. E., Suto M. J. (2018). Thrombospondin-1 regulation of latent TGF-β activation: a therapeutic target for fibrotic disease. Matrix Biol. 68-69 28–43. 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafian B., Fogo A. B., Lusco M. A., Alpers C. E. (2015). AJKD atlas of renal pathology: diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 66 e37–e38. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao A., Afrakhte M., Morén A., Nakayama T., Christian J. L., Heuchel R., et al. (1997a). Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature 389 631–635. 10.1038/39369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao A., Imamura T., Souchelnytskyi S., Kawabata M., Ishisaki A., Oeda E., et al. (1997b). TGF-beta receptor-mediated signalling through Smad2, Smad3, and Smad4. EMBO J. 16 5353–5362. 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchapakesan U., Pegg K., Gross S., Komala M. G., Mudaliar H., Forbes J., et al. (2013). Effects of SGLT2 inhibition in human kidney proximal tubular cells–renoprotection in diabetic nephropathy? PLoS One 8:e54442. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardali E., Sanchez-Duffhues G., Gomez-Puerto M. C., Ten Dijke P. (2017). TGF-β-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition in fibrotic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:2157. 10.3390/ijms18102157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parving H. H., Lehnert H., Bröchner-Mortensen J., Gomis R., Andersen S., Arner P. (2001). The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 345 870–878. 10.1056/NEJMoa011489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkovic V., Jardine M. J., Neal B., Bompoint S., Heerspink H. J. L., Charytan D. M., et al. (2019). Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 380 2295–2306. 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M., Thorikay M., Deckers M., van Dinther M., Grygielko E. T., Gellibert F., et al. (2008). Oral administration of GW788388, an inhibitor of TGF-beta type I and II receptor kinases, decreases renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 73 705–715. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourgholamhossein F., Rasooli R., Pournamdari M., Pourgholi L., Samareh-Fekri M., Ghazi-Khansari M., et al. (2018). Pirfenidone protects against paraquat-induced lung injury and fibrosis in mice by modulation of inflammation, oxidative stress, and gene expression. Food Chem. Toxicol. 112 39–46. 10.1016/j.fct.2017.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W., Chen X., Polhill T. S., Sumual S., Twigg S., Gilbert R. E., et al. (2006). TGF-beta1 induces IL-8 and MCP-1 through a connective tissue growth factor-independent pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 290 F703–F709. 10.1152/ajprenal.00254.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RamachandraRao S. P., Zhu Y., Ravasi T., McGowan T. A., Toh I., Dunn S. R., et al. (2009). Pirfenidone is renoprotective in diabetic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20 1765–1775. 10.1681/asn.2008090931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjabi S., Zenewicz L. A., Kamanaka M., Flavell R. A. (2009). Anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory roles of TGF-beta, IL-10, and IL-22 in immunity and autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 9 447–453. 10.1016/j.coph.2009.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., Ix J. H., Mathew A. V., Cho M., Pflueger A., Dunn S. R., et al. (2011). Pirfenidone for diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22 1144–1151. 10.1681/asn.2010101049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., Jin Y., Guo J., Ziyadeh F. N. (1996). Neutralization of TGF-beta by anti-TGF-beta antibody attenuates kidney hypertrophy and the enhanced extracellular matrix gene expression in STZ-induced diabetic mice. Diabetes 45 522–530. 10.2337/diab.45.4.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D. (2004). Roles of alphav integrins in vascular biology and pulmonary pathology. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16 552–557. 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihab F. S., Bennett W. M., Tanner A. M., Andoh T. F. (1997). Angiotensin II blockade decreases TGF-beta1 and matrix proteins in cyclosporine nephropathy. Kidney Int. 52 660–673. 10.1038/ki.1997.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull M. M., Ormsby I., Kier A. B., Pawlowski S., Diebold R. J., Yin M., et al. (1992). Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature 359 693–699. 10.1038/359693a0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureshbabu A., Muhsin S. A., Choi M. E. (2016). TGF-beta signaling in the kidney: profibrotic and protective effects. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 310 F596–F606. 10.1152/ajprenal.00365.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutariya B., Jhonsa D., Saraf M. N. (2016). TGF-β: the connecting link between nephropathy and fibrosis. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 38 39–49. 10.3109/08923973.2015.1127382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetwyne M. T., Gruenwald A., Niranjan T., Nishinakamura R., Strobl L. J., Susztak K. (2015). Notch1 and Notch2 in podocytes play differential roles during diabetic nephropathy development. Diabetes 64 4099–4111. 10.2337/db15-0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueberham E., Löw R., Ueberham U., Schönig K., Bujard H., Gebhardt R. (2003). Conditional tetracycline-regulated expression of TGF-beta1 in liver of transgenic mice leads to reversible intermediary fibrosis. Hepatology 37 1067–1078. 10.1053/jhep.2003.50196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker J., Berg P. H., Sheetz M., Duffin K., Shen T., Moser B., et al. (2017). Anti-TGF-1 antibody therapy in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28 953–962. 10.1681/asn.2015111230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. W., Liou N. H., Cherng J. H., Chang S. J., Ma K. H., Fu E., et al. (2014). siRNA-targeting transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor reduces wound scarring and extracellular matrix deposition of scar tissue. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134 2016–2025. 10.1038/jid.2014.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigert C., Brodbeck K., Klopfer K., Häring H. U., Schleicher E. D. (2002). Angiotensin II induces human TGF-beta 1 promoter activation: similarity to hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 45 890–898. 10.1007/s00125-002-0843-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipff P.-J., Hinz B. (2008). Integrins and the activation of latent transforming growth factor beta1 - an intimate relationship. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 87 601–615. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. G., Panchapakesan U., Qi W., Silva D. G., Chen X. M., Pollock C. A. (2011). Cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor inhibitor (PXS25) inhibits fibrosis in human proximal tubular cells by inhibiting conversion of latent to active TGF-beta1. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301 F84–F93. 10.1152/ajprenal.00287.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier S., Vasko R., Matsumoto K., Zullo J. A., Chen R., Maizel J., et al. (2015). Curtailing endothelial TGF-β signaling is sufficient to reduce endothelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrosis in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26 817–829. 10.1681/ASN.2013101137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Jiang H., Zhang Q., Mehrotra S., Abel P. W., Toews M. L., et al. (2016). Upregulation of RGS2: a new mechanism for pirfenidone amelioration of pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 17:103. 10.1186/s12931-016-0418-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Cui W. H., Zhou W. C., Li D. L., Li L. C., Zhao P., et al. (2017). Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signalling is required for TGF-beta/Smad2/3 signalling during myofibroblast proliferation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 21 1545–1554. 10.1111/jcmm.13085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Yang S., Huang J., Ruan S., Zheng Z., Lin J. (2012). Tgf-β1 induces autophagy and promotes apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 29 781–790. 10.3892/ijmm.2012.911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Liu Z., Chen Y. (2009). Regulation of TGF-beta signaling by Smad7. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 41 263–272. 10.1093/abbs/gmp018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D., Livingston M. J., Liu Z., Dong G., Zhang M., Chen J. K., et al. (2018). Autophagy in diabetic kidney disease: regulation, pathological role and therapeutic potential. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75 669–688. 10.1007/s00018-017-2639-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechel J., Gohil H., Lust W. D., Cohen A. (2002). Alterations in matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 expression in a transforming growth factor-beta transgenic model of hydrocephalus. J. Neurosci. Res. 69 662–668. 10.1002/jnr.10326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisberg M., Hanai J., Sugimoto H., Mammoto T., Charytan D., Strutz F., et al. (2003). BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat. Med. 9 964–968. 10.1038/nm888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Long J., Jiang W., Shi Y., He X., Zhou Z., et al. (2016). Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 375 905–906. 10.1056/NEJMc1602469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Huang W. (2018). Transforming Growth Factor beta1 (TGF-beta1)-Stimulated Integrin-Linked Kinase (ILK) Regulates Migration and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) of Human Lens Epithelial Cells via Nuclear Factor kappaB (NF-kappaB). Med. Sci. Monit. 24 7424–7430. 10.12659/MSM.910601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziyadeh F. N., Hoffman B. B., Han D. C., Iglesias-De La Cruz M. C., Hong S. W., Isono M., et al. (2000). Long-term prevention of renal insufficiency, excess matrix gene expression, and glomerular mesangial matrix expansion by treatment with monoclonal antitransforming growth factor-beta antibody in db/db diabetic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 8015–8020. 10.1073/pnas.120055097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]