Abstract

Discovery of potential bioactive metabolites from sponge-associated bacteria have gained attraction in recent years. The current study explores the potential of sponge (Suberea mollis) associated bacteria against bacterial and fungal pathogens. Sponge samples were collected from Red sea in Obhur region, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Of 29 isolated bacteria belong to four different classes i.e. Firmicutes (62%), γ-Proteobacteria (21%), α-Proteobacteria (10%) and Actinobacteria (7%). Among them nineteen (65%) bacterial strains showed antagonistic activity against oomycetes and only 3 (10%) bacterial strains were active against human pathogenic bacteria tested. Most bioactive genera include Bacillus (55%), Pseudovibrio (13%) and Ruegeria (10%). Enzyme production (protease, lipase, amylase, cellualse) was identified in 12 (41%) bacterial strains where potential strains belonging to γ-Proteobacteria and Firmicutes groups. Production of antimicrobial metabolites and hydrolysates in these bacteria suggest their potential role in sponge against pathogens. Further bioactive metabolites from selected strain of Vibrio sp. EA348 were identified using LC-MS and GC–MS analyses. We identified many active metabolites including antibiotics such as Amifloxacin and fosfomycin. Plant growth hormones including Indoleacetic acid and Gibberellin A3 and volatile organic compound such as methyl jasmonate were also detected in this strain. Our results highlighted the importance of marine bacteria inhabiting sponges as potential source of antimicrobial compounds and plant growth hormones of pharmaceutical and agricultural significance.

Keywords: Marine sponge, Antagonistic activity, 16S rRNA gene sequence, Enzymatic activity, Bioactive metabolites

1. Introduction

Marine environment always represent as a source of bioactive compounds discovery due to immense biodiversity, diverse environmental conditions and production of secondary metabolites by marine plants, invertebrates, and their associated microbial communities (Tulp and Bohlin, 2005). Infectious diseases become a serious health risk in many developing countries including Saudi Arabia (Devasahayam et al., 2010, Memish et al., 2014). Therefore, there is a need for discovery of new antibiotics to combat with emerging infectious diseases. Marine environment, particularly sponges remain a source of interest for searching natural products and bioactive compounds. Previous studies have reported that more than 15,000 natural compounds were isolated from marine invertebrates especially bioactive compounds and antibiotics from sponges (Brinkmann et al., 2017). Most of the secondary metabolites from marine environment are of microbial origin and diverse in their function exhibiting antiviral, antifungal, immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and many other function of biotechnological and (Imhoff et al., 2011, Taylor et al., 2007) pharmaceutical significance.

Marine natural products with range of biotechnological importance have been isolated from sponges, corals, tunicates, mollusks, algae, bryozoans, and associated microorganisms (Bhatnagar and Kim, 2010). Marine invertebrates harbor higher abundance of symbiotic microorganisms than in seawater environment (Thomas et al., 2010, Hentschel et al., 2006). These symbiotic microorganisms are producers of diverse range of bioactive compounds especially important for drug discovery. Symbiotic microbial communities also play an important role in chemical defense of their host sponge against different predators. This strategy of symbiotic microbes plays a key role in survival of sponge in the marine ecosystem (Hay, 2009). In recent years, many bioactive secondary metabolites were identified from sponges and more than 300 new and novel bioactive compounds were discovered from a single phylum Porifera and subjected to preclinical and clinical trials (Blunt et al., 2016). The dominant phyla as a producer of bioactive compounds are Actinobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in different species of marine sponges i.e Haliclona, Petrosia, Theonella, Dysidea, Xestospongia, Callyspongia, Halichondria, Aplysina, Xestospongia, and Sarcophyton sp. (Banakar et al., 2019)

Microbial communities producing bioactive compounds either live symbiotically or attach transiently with the host. To unravel interaction of sponge and symbiotic microbial communities, it is important to characterize and identify them from marine sponges. Many previous studies including culture dependent and independent techniques were used to identify bacterial communities associated with host sponges and until now more than 39 different phyla have been identified from marine sponges (Pita et al., 2018). Several studies have been performed to isolate and screen bacteria from marine sponges for the production of bioactive metabolites (Indraningrat et al., 2016).

Marine sponge Suberea mollis included in this study is already known for it's biotechnological importance and capable of producing bioactive and antioxidant compounds (Abbas et al., 2014). While in another study potent protective effect of S. mollis sponge extract was evident against carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) induced liver damage (Shaala et al., 2011). This marine sponge is not studied previously to isolate and identify bacterial communities using culturomics. Therefore this study is conducted to investigate bacterial communities associated with sponge and identify antagonistic bacteria producing bioactive metabolites.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Sample collection

Sponge specimens (three replicates) were collected at the depth of 30–40 m from the Red Sea in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. After collection, sponge samples were covered by seawater inside sterile plastic bags and transported to the laboratory for further identification and experiments. Sponge samples were identified as Suberea mollis, by Prof. Mohsin Al-Sofyani from King Abdulaziz University Jeddah.

2.2. Isolation of bacteria from sponge samples

The sponge samples were rinsed thoroughly with sterile seawater several times and finally chopped and grounded. Aliquots of 100 µl serial dilutions (10-3, 10-4 and 10-5) in sterile and filtered seawater (FS) were spread on to different media use for isolation. Different isolation media were prepared in sea water i.e. half strength R2A (½ R2A), half Tryptic soy agar (½ TSA), half nutrient agar (½ NA), and marine agar (MA) in distilled water. To inhibit the fungal growth, cyclohexamide (50 µg/ml) was added to culturing media. Plates were then incubated at 28 °C for 5–7 days. Single colonies grown on the plates were purified and further sub-cultured using 1/10 R2A medium. For further use purified bacterial strains were stored at −70 °C in 15% (v/v) glycerol.

2.3. Bacterial DNA extraction and 16S rDNA gene analysis

The bacterial strains were subjected to genomic DNA extraction and subsequent 16S rDNA gene analysis for identification. Using commercial genomic DNA extraction kit (Qiagen) genomic DNA was extracted. Bacterial universal primers were used for amplifications of 16S rRNA gene as described previously (Bibi et al., 2018). Using PCR purification kit (Qiagen) the PCR products were purified and further sequenced. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of all isolates were compared with sequences of related closest type strains obtained from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and using the EzBioCloud Database (https://www.ezbiocloud.net). The closest type species match and the percent sequence similarity were recorded. Using CLUSTAL_X version 1.83 (Thompson et al., 1997) alignments of 16S rRNA gene sequences were performed. For editing of gaps between sequences, BioEdit software version 4.7.3 (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html) was used. By using the neighbour-joining method in a MEGA7 Program (Kumar et al., 2016), phylogenetic tree was generated based on 16S rRNA gene sequences.

2.4. Analysis of antagonistic activity against oomycetes

Bacterial isolates were checked for their antagonistic activity against oomycete pathogens in vitro confrontation bioassay confrontation bioassay (Bibi et al., 2018). Phytophthora capsici and Pythium ultimum were maintained using V8 juice agar (1.0 g CaCO3, 100 ml of carrot juice, in 17.0 g agar in distilled water) and potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco Laboratories), respectively. Screening of bacteria was performed using modified PDA and V8 media [½PDA + V8 juice agar supplemented with ½ R2A] using paper disc method as described previously (Bibi et al., 2018). All bacterial isolates were tested in replicates against test pathogens. The inhibitory activity was measured by checking the inhibition zone of fungus around bacterial streak.

2.5. Screening of bacteria for antibacterial and enzymatic activities

To check antibacterial activity, antagonistic bacteria were screened against different pathogenic bacterial test strains. Test strains of pathogenic bacteria (Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, Enterococcus faecium ATCC 27270, Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853) were pregrown in LB broth for 24hrs at 37 °C. Antagonistic bacteria were grown on ½ R2A media 24hrs at 28 °C and then overlaid with 0.1% soft agar mixed with test strains at final concentration of A600 = 0.1. Further these plates were placed at 28 °C and were checked after 48hrs and the zone of inhibition was recorded. Antagonistic bacteria were further screened for their extracellular enzymatic production. Using skim milk ½ R2A agar media, proteolytic activity was checked. Starch media was used for checking for production of amylase. Positive strains show hydrolysis of starch as a clear zone on agar plates.

2.6. Optimization of bacterial culture conditions and identification of metabolites using LC-MS and GC–MS analyses

From 19 different antagonistic bacteria, based on low similarity and high antagonistic activity one strain Vibrio sp. EA348 was selected for identification of active metabolites. For optimization of culture conditions for Vibrio sp. EA348 four different i.e. ½NB, ½ TSB, ½ R2A and Marine broth were used. Vibrio sp. EA348 was cultured for 72 h and optical density (OD) was checked after 24hrs. Antifungal activity of culture was also assessed against P. capsici, Py. ultimum after every 24 hrs. In ½ R2A Vibrio sp. EA348 showed maximum inhibitory activity. Using ½ R2A culturing medium, different ranges of temperatures (20–40 °C) were used to check optimum temperature. Similarly different ranges of pH (5–12) were used. Vibrio sp. EA348 was grown in culture under optimized conditions for 36 hrs. Bacterial culture of 5 ml was placed at −70 °C for 5mins and then transfer to water bath at 37 °C for 5 mins. Repeat this process 5 times and then centrifuge it for 15 mins at 13000g. After centrifugation, 3 ml of supernatant was mixed with 12 ml of acetonitrile and vortexed for 30sec. Centrifuged again (13000g for 15 mins) and 300 µl supernatant was used for LC-MS analysis. Samples were analyzed on Agilent 6540B TOF/Q-TOF Mass Spectrometer integrated with Agilent 1290 UPLC and Dual AJS ESI source under conditions described previously (Bibi et al., 2018a). Raw data obtained was transfer to Agilent Mass Hunter Qualitative Analysis B.06.00 software for analysis. Metabolites of Vibrio sp. EA348 were identified by in-house database. For GC–MS analysis, 1 ml of bacterial culture was lysed and centrifuge for 10 min at 13000g. Approx. 300ul of supernatant was transferred to new Eppendorf tube and acetonitrile (600 µl) was added and vortex for 50sec. Further samples were centrifuge for 15 min at 12000g and 300 µl supernatant was transfer to a new glass vials and by using nitrogen dry machine solvent was removed. Then methoxyamine HCl in Pyridine (80 µl) was added to the glass vials, vortexed (1 min) and incubated for 30 min (at 70 °C). Further N, O-Bis (trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (80 μl) containing 1% (v/v) trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) was added and mixed briefly by vortexing (2–3 min) and finally derivatized for 30 min at 80 °C. Mixtures were centrifuged at 12000g (15 min) and 100 μl supernatant was further used for GC–MS analysis. Samples were analyzed using Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 Ultra under conditions described previously (Bibi et al., 2018b).

2.7. Statistical analysis

We used PubChem (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), ChemSpider (http://www.chemspider.com/), SciFinder (http://www.cas.org/products/scifinder), ChEMBL (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) databases to identify bacterial metabolites. The CSV file obtained after alignment with statistic compare component.

2.8. Nucleotide sequence number

Nucleotide sequences obtained from sponge-associated bacteria were deposited to GenBank database under accession numbers KY655446–KY655474.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of bacteria from sponge sample

Sponge sample, Suberea mollis was collected and studied for isolation and identification of associated bacterial symbionts (Fig. 1). To culture bacteria from sponge sample different types of culturing media (½ R2A, ½ TSA, ½ NA, and MA) were used. Bacteria were recovered on different media vary in their number and morphology. High percentage of bacteria was recovered on ½ R2A and MA while ½ TSA and ½ NA showed less number and diversity of bacteria when checked morphology. It indicates that ½ R2A and MA favor growth of bacteria from sponge. High concentration of nutrients in other two media may not support marine bacteria to grow. Therefore, it is important to use different composition and concentration of media to get maximum number of bacteria from any source use for isolation of bacteria. A total of 29 different bacteria were isolated from S. mollis using different culturing media mentioned above (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Sample of marine sponge, Suberea mollis collected from Red sea.

Table 1.

Taxonomic identification, antifungal and antibacterial activity of bacteria from sponge, Suberea mollis.

| Lab no | Accession Number | Similarity with closest type straina | Identityb (%) | Antifungal activityc |

Antibacterial acitivityd |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. capsici | P. ultimum | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | E. coli | E. faecalis | ||||

| EA345 | KY655446 | Ruegeria arenilitoris G-M8(T) | 99.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA346 | KY655447 | Bacillus persicus B48(T) | 98.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA347 | KY655448 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | 99.5 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA348 | KY655449 | Vibrio sagamiensis LC2-047(T) | 98.1 | 11 | 11 | – | – | – | – |

| EA349 | KY655450 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | 98.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA350 | KY655451 | Bacillus nealsonii DSM15077(T) | 99.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA351 | KY655452 | Brachybacterium muris C3H-21(T) | 99.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA352 | KY655453 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus NBRC12711(T) | 99 | 6 | 3 | – | – | – | 3 |

| EA353 | KY655454 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus subsp Bovis GTC 843(T) | 100 | 6 | 10 | – | – | – | – |

| EA354 | KY655455 | Bacillus paralicheniformis KJ-16(T) | 99 | 6 | 6 | – | – | – | – |

| EA355 | KY655456 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | 98.8 | – | – | – | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| EA356 | KY655457 | Ruegeria conchae TW15(T) | 97.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA357 | KY655458 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | 99.2 | 6 | 6 | 3 | |||

| EA358 | KY655459 | Bacillus licheniformis ATCC14580(T) | 97.4 | 4 | 10 | – | – | – | – |

| EA359 | KY655460 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. Inaquosorum KCTC13429(T) | 99.5 | 5 | 11 | – | – | – | – |

| EA360 | KY655461 | Bacillus siamensis KCTC13613(T) | 99.5 | 5 | 5 | – | – | – | – |

| EA361 | KY655462 | Bacillus paralicheniformis KJ-16(T) | 99.3 | 5 | 5 | – | – | – | – |

| EA362 | KY655463 | Bacillus campisalis SA2-6(T) | 99.4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA363 | KY655464 | Bacillus subterraneus DSM13966(T) | 99.5 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA364 | KY655465 | Bacillus nealsonii DSM15077(T) | 99.3 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA365 | KY655466 | Bacillus safensis FO-36b(T) | 99.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA366 | KY655467 | Bacillus timonensis 10403023(T) | 98.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EA367 | KY655468 | Bacillus nealsonii DSM 15077 (T) | 99 | 4 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA368 | KY655469 | Bacillus badius MTCC1458(T) | 99.2 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA369 | KY655470 | Bacillus endolithicus JC267(T) | 98 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA370 | KY655471 | Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus DSM 23,493 (T) | 99.3 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA371 | KY655472 | Bacillus dabaoshanensis GSS04 (T) | 97.5 | 5 | 10 | – | – | – | – |

| EA372 | KY655473 | Ruegeria conchae TW15(T) | 99.4 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

| EA373 | KY655474 | Micrococcus aloeverae AE-6 (T) | 99.9 | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – |

Identification of bacterial strain based on partial 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses.

% similarity of each bacterial strain with closely related type strain.

Antagonistic activity of sponge-associated bacteria. The activity was measured after 4–5 days incubation at 28 °C by measuring the clear zone of fungal growth inhibition: −, Negative; +, 3 mm; ++, between 4 and 6 mm; +++, between 7 and 9 mm; ++++, between 10 and 12.

Antibacterial activity against human pathogenic bacteria: −, Negative; +, 3 mm. ++, between 4 and 6 mm.

3.2. Antimicrobial activity of sponge-associated bacteria

Twenty-nine bacteria isolates from marine sponge S. mollis were screened against oomycetes i.e. Py. ultimum and P. capsici and pathogenic bacteria i.e. S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis and E. coli. From sponge S. mollis, nineteen (65%) bacterial strains were active against oomycetes from total twenty-nine. Five different classes of bacteria i.e. Firmicutes (n = 18; 62%), γ-Proteobacteria (n = 6; 21%), α-Proteobacteria (n = 3; 10%) and Actinobacteria (n = 2; 7%) were identified from S. mollis (Table 1). Bacterial strains were checked for their inhibitory activity against human pathogenic bacteria by using agar spot test. Only 3 (10%) bacteria from S. mollis were able to inhibit pathogenic bacteria in an in vitro assay. From these active isolates, strain EA355 belong to Pseudovibrio sp. showed only antibacterial activity and was fail to inhibit fungal pathogens (Table 2). Strain EA352 exhibited antifungal as well as antibacterial activity. Dominant genus in this study from three marine sponges was Bacillus as 19 different species of this genus were detected from these sponges.

Table 2.

Bacterial enzymatic activities on different enzymatic media used for culturing.

| Lab no | Similarity with closest type straina | Enzymatic activity (mm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease | Lipase | Amylase | Cellualse | ||

| EA345 | Ruegeria arenilitoris G-M8(T) | 5 | – | – | – |

| EA346 | Bacillus persicus B48(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA347 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | 5 | |||

| EA348 | Vibrio sagamiensis LC2-047(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA349 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA350 | Bacillus nealsonii DSM15077(T) | 5 | – | – | – |

| EA351 | Brachybacterium muris C3H-21(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA352 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus NBRC12711(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA353 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus subsp Bovis GTC 843(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA354 | Bacillus paralicheniformis KJ-16(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA355 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA356 | Ruegeria conchae TW15(T) | 4 | |||

| EA357 | Pseudovibrio denitrificans DN34(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA358 | Bacillus licheniformis ATCC14580(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA359 | Bacillus subtilis subsp. Inaquosorum KCTC13429(T) | 6 | – | – | 5 |

| EA360 | Bacillus siamensis KCTC13613(T) | 7 | – | – | – |

| EA361 | Bacillus paralicheniformis KJ-16(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA362 | Bacillus campisalis SA2-6(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA363 | Bacillus subterraneus DSM13966(T) | 5 | – | – | – |

| EA364 | Bacillus nealsonii DSM15077(T) | 5 | 5 | – | |

| EA365 | Bacillus safensis FO-36b(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA366 | Bacillus timonensis 10403023(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA367 | Bacillus nealsonii DSM 15,077 (T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA368 | Bacillus badius MTCC1458(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA369 | Bacillus endolithicus JC267(T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA370 | Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus DSM 23493 (T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA371 | Bacillus dabaoshanensis GSS04 (T) | – | – | – | – |

| EA372 | Ruegeria conchae TW15(T) | – | – | – | 4 |

| EA373 | Micrococcus aloeverae AE-6 (T) | 5 | – | – | – |

Enzymatic activity was assessed as zone of halo formed around bacterial colonies: −, Negative; +, 3 mm; ++, between 4 and 5 mm; +++, between 6 and 7 mm.

3.3. Enzymatic activities of antagonistic bacteria

Production of cell wall lytic enzymes such as lipase, amylase, protease and cellulose activities of antagonistic bacteria were checked. These hydrolytic activities are summarized in Table 2. Isolates from S. mollis were potential for production of protease (n = 9, 31%) while cellulase (n = 2, 7%) and amylase (n = 1, 3%) activity was detected at low rate and no isolate was positive for production of lipase. The number of bacteria presenting protease production was high as compared to other enzymatic activities.

3.4. Phylogenetic analysis

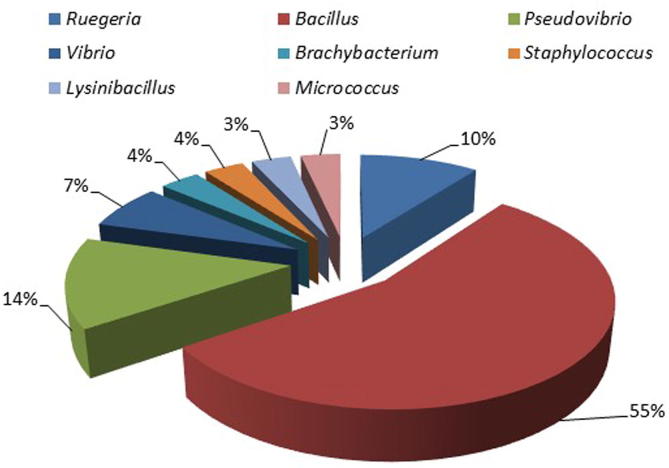

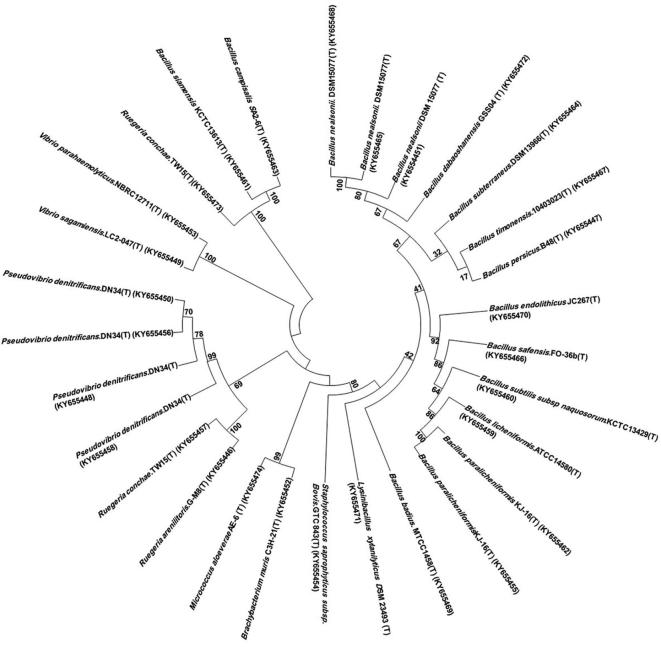

Bacterial identification was accomplished by amplification of 16S rRNA gene sequence. From sponge S. mollis, eight different genera were encountered i.e Reugeria, Bacillus, Pseudovibrio, Vibrio, Brachybacterium, Staphylococcus, Lysinibacillus, and Micrococcus belong to four different classes where Firmicutes (65%) was dominant class (Fig. 2). Sequence similarities of isolated bacteria were ranges from 97.4% to 100% from marine sponge S. mollis (Table 1). Some new and novel bacterial strains were also recovered in this study. To check phylogenetic relatedness, neighbor Joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree for antagonistic bacterial isolates was constructed using 16S rRNA gene sequence data (Fig. 3). Bootstrap values were high in phylogenetic tree.

Fig. 2.

Percentage composition of different genera of isolated bacteria from S. mollis on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic distribution of bacteria isolated from S. mollis on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequences from sponge-associated bacteria. The phylogenetic relationships were inferred using the neighbor-joining method with the Jukes-Cantor algorithm. Bootstrap values (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.

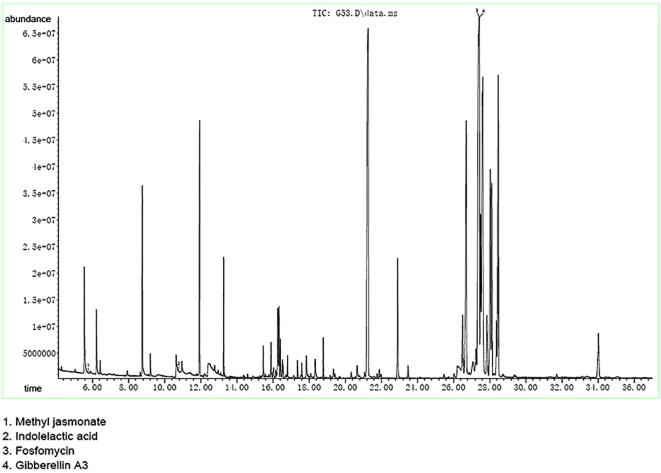

3.5. GC–MS and LC-MS analyses for identification of metabolites

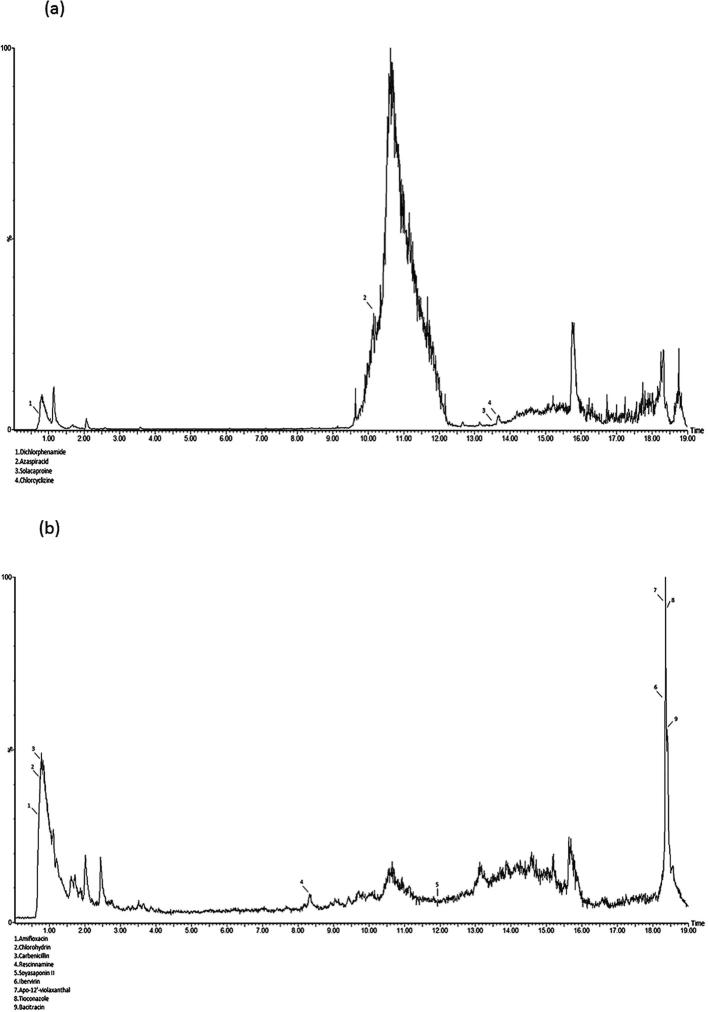

Vibrio sp. EA348 was selected from 19 different antagonistic bacteria and analyzed for presence of active metabolites using GC and LC-MS analyses. This strain was selected due to its low sequence similarity of 16S rRNA gene, taxonomic affiliation and high antifungal activity. LC and GC–MS analyses of Vibrio sp. EA348 showed presence of different chemical compounds in culture (Fig. 4a–b and Fig. 5). Results of LC-MS analysis from culture extract of Vibrio sp. EA348 identified different bioactive metabolites where main peaks of 6 secondary bioactive metabolites were present in both the positive- and negative-ion mode (Fig. 4a and b). These compounds include Amifloxacin, Carbenicillin, Rescinnamine, Chlorcyclizine, Tioconazole and Azaspiracids. While using GC–MS, mostly plant growth hormones i.e. Indoleacetic acid, Gibberellin A3 (GA3), methyl jasmonate and antibiotic fosfomycin was identified from culture extract. These compounds were identified by comparing their mass spectra with NIST library (Fig. 5). Bioactive metabolites and details of matching criteria/metrics are summarizing in Table 3.

Fig. 4.

Bioactive secondary metabolites in culture extract of strain Vibrio sp. EA348 detected by LC/MS analysis. (a) Positive mode LC/MS analysis and (b) negative mode LC/MS analysis.

Fig. 5.

Spectra of GC/MS analysis presenting detection secondary metabolites in strain Vibrio sp. EA348.

Table 3.

Secondary bioactive metabolites from crude extract of Vibrio sp. EA348.

| No | Compoundsa | Formula | RT (min)b | m/z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS (Positive mode) | ||||

| 1 | Dichlorphenamide | C6H6Cl2N2O4S2 | 0.7099 | 304.8993 |

| 2 | Azaspiracid | C47H71NO12 | 9.9789 | 864.4476 |

| 3 | Solacaproine | C18H39N3O | 13.5358 | 314.3455 |

| 4 | Chlorcyclizine | C18H21ClN2 | 13.6452 | 301.146 |

| LC-MS (Negative mode) | ||||

| 5 | Amifloxacin | C16H19FN4O3 | 0.6905 | 514.8378 |

| 6 | Chlorohydrin | C13H9ClO | 0.7464 | 215.0291 |

| 7 | Carbenicillin | C17H18N2O6S | 0.7932 | 377.0873 |

| 8 | Rescinnamine | C35H42N2O9 | 8.3892 | 633.299 |

| 9 | Soyasaponin II | C47H76O17 | 11.9654 | 911.5035 |

| 10 | Ibervirin | C5H9NS2 | 18.3267 | 146.0116 |

| 11 | Apo-12′-violaxanthal | C25H34O3 | 18.3338 | 381.2395 |

| 12 | Tioconazole | C16H13Cl3N2OS | 18.4002 | 384.9374 |

| 13 | Bacitracin | C66H103N17O16S | 18.4147 | 1420.71 |

| GC–MS | ||||

| 14 | Methyl jasmonate | C13H20O3 | 334.1442 | 94.08767 |

| 15 | Indolelactic acid | C11H11NO3 | 1647.6537 | 130.14 |

| 16 | Fosfomycin | C3H7O4P | 1645.381699 | 211.1417691 |

| 17 | Gibberellin A3 | C19H22O6 | 1648.43767 | 167.1247946 |

Bioactive compounds were identified through various databases and the in-house accurate mass database.

RT = retention time.

4. Discussion

Marine environment remain always an area of research for scientists all around the world. Extreme conditions of temperature and salinity in marine ecosystem provide unique and untapped microbiome. These unique environmental conditions become a source for exploration of new and novel microbes and their secondary compounds. Until now more than 20,000 different bioactive compounds have been discovered from marine fauna and flora (Choudhary et al., 2017). Bacterial communities associated with sponges are believed to be an important partner for host survival. Endosymbiotic microorganisms perform different functions in sponges and comprises of 40% of their total biomass.

Sponge S. mollis showed presence of potential strains of bacteria when screened against different pathogenic bacteria and fungi. The high number of antagonistic bacteria belong to group Firmicutes. Bioactivity of these antagonistic isolates was high against fungi as compare to human pathogenic bacteria. Regarding distribution of antagonistic bacteria associated with sponges, Actinobacteria was the most bioactive group following Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Cyanobacteria, Verrucomicrobia. Most of the sponge based antibiotics were derived from bacteria belong to Actinobacteria (Thomas et al., 2010, Fenical and Jensen, 2006). Different bioactive genera obtained in this study are already known for their antimicrobial properties. Antimicrobial activity of the genus Bacillus is well evident from terrestrial sources. Similar kind of bioactivities were reported from marine Bacillus spp. associated with sponges (Gebhardt et al., 2002, Anand et al., 2006, Kanagasabhapathy et al., 2008, Romanenko et al., 2008). Analysis of genome sequence in genus Bacillus revealed that this genus has potential to produce antibiotics-like compounds (Devi et al., 2010). Many Gram negative strains of genus Paenibacillus exhibited antimicrobial activity (Fickers, 2012, Kim et al., 2004). Strains of Staphylococcus isolated from marine sponge produce antimicrobial compounds (Tupinambá et al., 2008). Following Firmicutes, isolates of two phyla γ-Proteobacteria and α-Proteobacteria were more prevalent in this study. Bacterial strains belong to genus Ruegeria in α-Proteobacteria and two genera i.e. Pseudovibrio and Vibrio belonging to γ-Proteobacteria were identified. Sponge-associated antagonistic bacterial strains of γ- and α-Proteobacteria were identified in many previous studies. Many strains of Pseudovibrio showing spectra for different active compounds were recovered from marine sponges (Sertan-de Guzman et al., 2007). Marine vibrio species have been reported as source of many novel and new compounds. More than 93 different active metabolites were identified from Vibrionaceae. These are known to produce wide range of antibacterial compounds which ecologically favoring their population in sponges (Chen et al., 2012, Phelan et al., 2012). Two-thirds of antibiotics from natural sources were isolated from Actinobacteria. Novel and new chemical compounds have been recovered from marine taxa of Actinobacteria and Salinispora. Strains of Salinispora were cultured from marine sponge Pseudoceratina clavata (Kim et al., 2005). Only one antagonitsic strain of Micrococcus sp. EA373 is identified from sponge S. mollis in this study. Antimicrobial activity of the strains of Micrococcus associated with sponges has been observed (Abdelmohsen et al., 2010).

Two media, ½ R2A and MA were most efficient media for isolation of bacteria from sponge S. mollis. Fermentation conditions are important for production of bacterial secondary metabolites. These culturing conditions effects production of bioactive compounds and can be different in different strains of bacteria (Chen et al., 2000). Bacterial strain Vibrio sp. EA348 selected for identification of metabolites also showed maximum antimicrobial activity in ½ R2A liquid medium. We used both GC and LC-MS techniques to identify bioactive compounds. Several bioactive compounds including antibiotics and plant growth hormones were observed. These bioactive compounds including Amifloxacin, Carbenicillin, Rescinnamine, Chlorcyclizine, Tioconazole and Azaspiracids are already known for their broad spectrum antimicrobial properties. These compounds are synthetic or semi-synthetic in nature and identified first time from marine sponge-associated bacteria. Sponges associated microflora produced potent metabolites mainly glycosides, phenols, porphyrins, phenazines, alkaloids, terpenoids, polyketides and sterols. Many of these bioactive compounds are in clinical or preclinical trials (Mehbub et al., 2014). Brominated bioactive metabolites are reported from sponge S. mollis exhibiting activity against pathogenic bacteria S. aureus, P. aerugenosa, and K. pneumoniae (Abou-Shoer et al., 2008).

Strain Vibrio sp. EA348 showed close 16S rDNA gene similarity to Vibrio sagamiensis LC2-047 T that was isolated previously from sea water in Japan (Yoshizawa et al., 2010). There is no evidence and report for presence of bioactive compounds from this related type strain. While our study showed presence of broad spectrum bioactive compounds and phytohormones in strain EA348. Symbiotic or endophytic bacteria from terrestrial environment are already known for production of phytohormones. These phytohormones such as Indoleacetic acid and Gibberellin A3 play an important role in plant growth and defense mechanism (Sgroy et al., 2009). Volatile organic compound, methyl jasmonate help in root growth, seed germination and plant defense against different pathogens. These plant growth regulators and defense compounds synthesized by plant associated bacteria in response to abiotic and biotic stresses (Egamberdieva et al., 2017). The findings suggest that strains isolated from S. mollis are capable of producing antimicrobial compounds effective against pathogenic fungi and human pathogenic bacteria. Strain EA348 showed presence of bioactive secondary metabolites having implications in different health sector.

5. Conclusions

Our results confirm that potential bioactive secondary metabolites are produced by Vibrio sp. EA348 that is the most promising strain to work in future. Bacterial communities of sponges play a significant ecological role mainly the production of secondary antimicrobial metabolites for protection of host against different pathogens. Bioactive metabolites detected in Vibrio sp. EA348 have great biotechnological and medicinal importance due to antibacterial, antifungal and plant growth hormones production. There is no evidence or any study reported for presence of such bioactive compounds in strains of Vibrio. These sponge-associated bacterial communities have medical and biotechnological importance to search new and effective drugs for treatment of different diseases. Our results demonstrated the potential of bacterial communities associated with sponge Suberea mollis and open up the way for future studies.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant No. (DF-661-141-1441). The author therefore, gratefully acknowledge DSR technical and financial support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abbas A.T., El-Shitany N.A., Shaala L.A., Ali S.S., Azhar E.I., Abdel-Dayem U.A., Youssef D.T. Red Sea Suberea mollis sponge extract protects against CCl4-induced acute liver injury in rats via an antioxidant mechanism. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2014/745606. 745606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmohsen U.R., Pimentel-Elardo S.M., Hanora A., Radwan M., Abou-El-Ela S.H., Ahmed S., Hentschel U. Isolation, phylogenetic analysis and anti-infective activity screening of marine sponge-associated Actinomycetes. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:399–412. doi: 10.3390/md8030399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Shoer M.I., Shaala L.A., Youssef D.T., Badr J.M., Habib A.A.M. Bioactive brominated metabolites from the Red Sea sponge Suberea mollis. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71(8):1464–1467. doi: 10.1021/np800142n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand T.P., Bhat A.W., Shouche Y.S., Roy U., Siddharth J., Sarma S.P. Antimicrobial activity of marine bacteria associated with sponges from the waters off the coast of South East India. Microbiol. Res. 2006;161:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banakar, S.P., Karthik, L., Li, Z., 2019. Mass production of natural products from microbes derived from sponges and corals. In: Symbiotic Microbiomes of Coral Reefs Sponges and Corals. Springer, Dordrecht, 2019, pp. 505–526.

- Bhatnagar I., Kim S.K. Immense essence of excellence: marine microbial bioactive compounds. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8(10):2673–2701. doi: 10.3390/md8102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi F., Strobel G.A., Naseer M.I., Yasir M., Al-Ghamdi K., Ahmed A., Azhar E.I. Microbial flora associated with the halophyte-salsola imbricate and its biotechnical potential. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:65. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi, F., Naseer, M.I., Yasir, M, Al-Ghamdi, A.A., Azhar, E.I., 2018a. LC-MS based identification of secondary metabolites from marine antagonistic endophytic bacteria. Genet. Mol. Res. 17, gmr16039857. https://doi.org/10.4238/gmr16039857.

- Bibi F., Strobel G.A., Naseer M.I., Yasir M., Khalaf Al-Ghamdi A.A., Azhar E.I. Halophytes-associated endophytic and rhizospheric bacteria: diversity, antagonism and metabolite production. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2018;28:192–213. [Google Scholar]

- Blunt J.W., Copp B.R., Keyzers R.A., Munro M.H., Prinsep M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. Natural. 2016;33(3):382–431. doi: 10.1039/c5np00156k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann C., Marker A., Kurtböke D. An overview on marine sponge-symbiotic bacteria as unexhausted sources for natural product discovery. Diversity. 2017;9(4):40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Li X., Waters B., Davies J. Enhanced production of microbial metabolites in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Antibiotics. 2000;53:1145–1153. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.H., Kuo J., Sung P.J., Chang Y.C., Lu M.C., Wong T.Y., Liu J.K., Weng C.F., Twan W.H., Kuo F.W. Isolation of marine bacteria with antimicrobial activities from cultured and field-collected soft corals. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28(12):3269–3279. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary A., Naughton L., Montánchez I., Dobson A., Rai D. Current status and future prospects of marine natural products (MNPs) as antimicrobials. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15(9):272. doi: 10.3390/md15090272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devasahayam G., Scheld W.M., Hoffman P.S. Newer antibacterial drugs for a new century. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2010;19(2):215–234. doi: 10.1517/13543780903505092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi P., Wahidullah S., Rodrigues C., Souza L.D. The sponge-associated bacterium Bacillus licheniformis SAB1: A source of antimicrobial compounds. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8(4):1203–1212. doi: 10.3390/md8041203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egamberdieva, D., Wirth, S.J., Alqarawi, A.A., Abd_Allah, E.F., Hashem, A., 2017. Phytohormones and beneficial microbes: essential components for plants to balance stress and fitness. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fenical W., Jensen P.R. Developing a new resource for drug discovery: marine actinomycete bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:666–673. doi: 10.1038/nchembio841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fickers P. Antibiotic compounds from Bacillus: why are they so amazing? Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012;8:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt K., Schimana J., Müller J., Fiedler H.P., Kallenborn H.G., Holzenkämpfer M., Krastel P., Zeeck A., Vater J., Höltzel A., Schmid D.G. Screening for biologically active metabolites with endosymbiotic bacilli isolated from arthropods. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;217(2):199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay M.E. Marine chemical ecology: chemical signals and cues structure marine populations, communities, and ecosystems. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2009;1:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentschel U., Usher K.M., Taylor M.W. Marine sponges as microbial fermenters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006;55(2):167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff J.F., Labes A., Wiese J. Bio-mining the microbial treasures of the ocean: new natural products. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011;29:468–482. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indraningrat A., Smidt H., Sipkema D. Bioprospecting sponge-associated microbes for antimicrobial compounds. Mar. Drugs. 2016;14(5):87. doi: 10.3390/md14050087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagasabhapathy M., Sasaki H., Nagata S. Phylogenetic identification of epibiotic bacteria possessing antimicrobial activities isolated from red algal species of Japan. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;24:2315–2321. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.S., Bae C.Y., Jeon J.J., Chun S.J., Oh H.W. Paenibacillus elgii sp. nov., with broad antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004;54:2031–2035. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.K., Garson M.J., Fuerst J.A. Marine actinomycetes related to the ‘Salinospora’group from the Great Barrier Reef sponge Pseudoceratina clavata. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;7:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehbub M.F., Lei J., Franco C., Zhang W. Marine sponge derived natural products between 2001 and 2010: trends and opportunities for discovery of bioactives. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12(8):4539–4577. doi: 10.3390/md12084539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish Z.A., Jaber S., Mokdad A.H., AlMazroa M.A., Murray C.J., Al Rabeeah A.A. Peer reviewed: Burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 1990–2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E169. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan R.W., O’Halloran J.A., Kennedy J., Morrissey J.P., Dobson A.D., O’Gara F., Barbosa T.M. Diversity and bioactive potential of endospore-forming bacteria cultured from the marine sponge Haliclona simulans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;112:65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pita L., Rix L., Slaby B.M., Franke A., Hentschel U. The sponge holobiont in a changing ocean: from microbes to ecosystems. Microbiome. 2018;2018(6):46. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanenko L.A., Uchino M., Kalinovskaya N.I., Mikhailov V.V. Isolation, phylogenetic analysis and screening of marine mollusc-associated bacteria for antimicrobial, hemolytic and surface activities. Microbiol. Res. 2008;163:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sertan-de Guzman A.A., Predicala R.Z., Bernardo E.B., Neilan B.A., Elardo S.P., Mangalindan G.C., Tasdemir D., Ireland C.M., Barraquio W.L. Pseudovibrio denitrificans strain Z143–1, a heptylprodigiosin-producing bacterium isolated from a Philippine tunicate. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007;277(2):188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgroy V., Cassán F., Masciarelli O., Del Papa M.F., Lagares A., Luna V. Isolation and characterization of endophytic plant growth-promoting (PGPB) or stress homeostasis-regulating (PSHB) bacteria associated to the halophyte Prosopis strombulifera. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;85:371–381. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaala L.A., Bamane F.H., Badr J.M., Youssef D.T. Brominated arginine-derived alkaloids from the red sea sponge suberea mollis. J. Nat. Prod. 2011;74:1517–1520. doi: 10.1021/np200120d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.W., Radax R., Steger D., Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T.R., Kavlekar D.P., LokaBharathi P.A. Marine drugs from sponge-microbe association-A review. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:1417–1468. doi: 10.3390/md8041417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Gibson T.J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D.G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulp M., Bohlin L. Rediscovery of known natural compounds: nuisance or goldmine? Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005;13:5274–5282. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupinambá G., Da Silva A.J., Alviano C.S., Souto-Padron T.C., Seldin L., Alviano D.S. Antimicrobial activity of Paenibacillus polymyxa SCE2 against some mycotoxin-producing fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;105:1044–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa S., Wada M., Yokota A., Kogure K. Vibrio sagamiensis sp. nov., luminous marine bacteria isolated from sea water. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;56:499–507. doi: 10.2323/jgam.56.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]