This secondary analysis of the ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial describes sex differences in stress testing, coronary computed tomographic angiography findings, and symptoms in patients with stable ischemic heart disease.

Key Points

Question

When considering patients who have obstructive coronary artery disease and ischemia on stress testing, are there sex differences in severity of coronary artery disease, ischemia, and/or symptoms?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of the ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial of 5179 patients, women had more frequent angina, less extensive coronary artery disease, and less severe ischemia than men. On multivariate analysis, female sex was independently associated with greater angina frequency.

Meaning

There may be inherent sex differences in the complex relationships between angina, ischemia, and atherosclerosis that may have implications for testing and treatment of patients with suspected coronary artery disease.

Abstract

Importance

While many features of stable ischemic heart disease vary by sex, differences in ischemia, coronary anatomy, and symptoms by sex have not been investigated among patients with moderate or severe ischemia. The enrolled ISCHEMIA trial cohort that underwent coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) was required to have obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) for randomization.

Objective

To describe sex differences in stress testing, CCTA findings, and symptoms in ISCHEMIA trial participants.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of the multicenter ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial analyzed baseline characteristics of patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Individuals were enrolled from July 2012 to January 2018 based on local reading of moderate or severe ischemia on a stress test, after which blinded CCTA was performed in most. Core laboratories reviewed stress tests and CCTAs. Participants with no obstructive CAD or with left main CAD of 50% or greater were excluded. Those who met eligibility criteria including CCTA (if performed) were randomized to a routine invasive or a conservative management strategy (N = 5179). Angina was assessed using the Seattle Angina Questionnaire. Analysis began October 1, 2018.

Interventions

CCTA and angina assessment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Sex differences in stress test, CCTA findings, and symptom severity.

Results

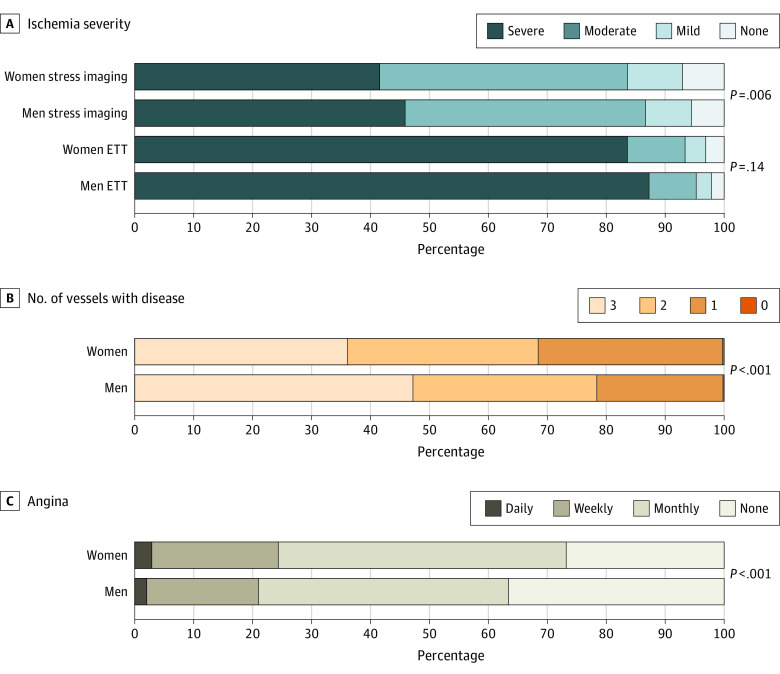

Of 8518 patients enrolled, 6256 (77%) were men. Women were more likely to have no obstructive CAD (<50% stenosis in all vessels on CCTA) (353 of 1022 [34.4%] vs 378 of 3353 [11.3%]). Of individuals who were randomized, women had more angina at baseline than men (median [interquartile range] Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency score: 80 [70-100] vs 90 [70-100]). Women had less severe ischemia on stress imaging (383 of 919 [41.7%] vs 1361 of 2972 [45.9%] with severe ischemia; 386 of 919 [42.0%] vs 1215 of 2972 [40.9%] with moderate ischemia; and 150 of 919 [16.4%] vs 394 of 2972 [13.3%] with mild or no ischemia). Ischemia was similar by sex on exercise tolerance testing. Women had less extensive CAD on CCTA (205 of 568 women [36%] vs 1142 of 2418 men [47%] with 3-vessel disease; 184 of 568 women [32%] vs 754 of 2418 men [31%] with 2-vessel disease; and 178 of 568 women [31%] vs 519 of 2418 men [22%] with 1-vessel disease). Female sex was independently associated with greater angina frequency (odds ratio, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.76).

Conclusions and Relevance

Women in the ISCHEMIA trial had more frequent angina, independent of less extensive CAD, and less severe ischemia than men. These findings reflect inherent sex differences in the complex relationships between angina, atherosclerosis, and ischemia that may have implications for testing and treatment of patients with suspected stable ischemic heart disease.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01471522

Introduction

Among patients with stable ischemic heart disease and acute coronary syndromes, women have a lesser extent of coronary atherosclerosis than men, despite a consistently higher risk profile including older age at presentation and a greater frequency of comorbidities.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 However, epicardial obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) is more common among men, even when considering only patients with typical angina.10 In contrast, microvascular coronary dysfunction is more commonly seen among women as a cause of stable ischemic heart disease.11,12 Coronary artery spasm is a potential contributor to symptoms as well.13

Given the lower prevalence of obstructive CAD, previous studies have shown that diagnostic accuracy of stress testing is lower among women than men when considering the reference standard of obstructive CAD. In both sexes, specificity of stress testing for angiographically obstructive coronary stenoses is greater when a higher threshold for ischemia is used with various nonimaging stress testing modalities. Much of this evidence is from years past, used varied definitions for ischemia, and is fraught with selection bias. A contemporary evaluation of accuracy is not available. It remains unknown whether a more rigorous determination of the extent and severity of ischemia, using standardized approaches, increases the accuracy of testing to identify obstructive CAD in women.

The International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial (NCT01471522) enrolled and randomized participants based on the severity of ischemia and the presence of obstructive CAD. The main objective of this report was to analyze the possible sex differences in symptoms, ischemia severity, and anatomic severity of disease in the ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial cohort because this trial cohort provides fewer confounding effects from the lower likelihood of finding any epicardial CAD in women.

Methods

The design of the ISCHEMIA trial has been published in detail.14,15 In brief, patients with known or suspected stable ischemic heart disease were selected for enrollment based on the finding of moderate or severe ischemia on a stress imaging test or severe ischemia on a nonimaging exercise tolerance test (ETT) and provided written informed consent. Ischemia severity was determined by sites before enrollment and assessed independently by experienced core laboratories. Thus, some randomized participants were deemed by core laboratories not to have moderate or severe ischemia, even though they were eligible for randomization by site determination of ischemia severity. Key exclusion criteria were acute coronary syndrome within the prior 2 months, left ventricular ejection fraction less than 35%, estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min, unacceptable angina severity despite maximal medical therapy, heart failure exacerbation within the last 6 months, or New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) was performed with the goal of excluding from randomization patients with 50% or greater left main coronary stenosis and participants with less than 50% stenosis of an epicardial coronary artery. Coronary computed tomography angiography was not required when estimated glomerular filtration rate was less than 60 mL/min or coronary anatomy was known to meet entry criteria based on prior testing, typically prior invasive angiography.14,16 Race/ethnicity were self-reported. Fully eligible participants were randomized to an invasive strategy or a conservative strategy.14 The study was approved by the NYU School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

In this report, enrolled refers to patients who signed consent and were enrolled in the trial, and randomized refers to those who were randomized to the invasive vs conservative strategy. Screening logs were completed at sites intermittently as requested by the clinical coordinating center, recording only patients locally determined to meet ischemia entry criteria.

The predictive accuracy of stress testing for obstructive CAD was assessed by comparing the proportion of participants with obstructive disease who did and did not meet various trial defined stress test criteria. Values were computed comparing women vs men among patients whose stress test did vs did not meet trial defined criteria per the core laboratory.

Stress Imaging Definitions

On nuclear imaging, ischemia was quantified based on percent reversible ischemia of the left ventricle on a myocardial perfusion scan (severe, ≥15%; moderate, 10% to <15%; mild, 5% to <10%; none, <5%). On stress echocardiography, ischemia was quantified based on the number of segments with inducible hypokinesia or akinesia (severe, ≥4; moderate, 3; mild, 1 or 2; none, 0). On stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, ischemia was quantified based on percent reversible ischemia of the left ventricle (severe, ≥15%; moderate, 10% to <15%; mild, 5% to <10%; none, <5%). On nonimaging ETT, ischemia was categorized based on ST depression and workload (severe, ≥1.5 mm ST depression in 2 leads or ≥2 mm ST depression in 1 lead at a specified workload on exercise tolerance testing in the presence of exertional angina before or during the stress test; see Chiha et al4 for additional categories). Image interpretation used standard segmental models.17

CCTA Definitions

The Duke prognostic index is a validated ordinal categorical scale of severity of CAD based on CCTA.18 The segment stenosis score is defined as the sum across 16 coronary segments, with segmental score assigned as 0 if 0% stenosis, 1 if 1% to 24% stenosis, 2 if 25% to 49% stenosis, 3 if 50% to 69% stenosis, and 4 if 70% to 100% stenosis. The segment involvement score is defined similarly to the segment stenosis score, but the per-segment score is 0 for 0% stenosis and 1 for 1% to 100% stenosis.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics are presented for enrolled participants by sex and randomized participants by sex. Data collection for enrolled participants who were not randomized was much less extensive than for those who were randomized. Imaging test results presented here represent core laboratory evaluation. Reasons for screen failure were tabulated by sex.

Differences between women and men were assessed using the χ2 test or Cochran-Armitage trend test to account for the ordered nature of categories. Continuous variables are presented as the number of nonmissing values and median (Q1, Q3); differences were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

The accuracy of stress testing for obstructive CAD was assessed by comparing the proportion of participants with obstructive CAD (separately for ≥50% and ≥70% stenosis) for participants who did vs did not meet trial-defined stress test criteria. For women and men, the risk ratio (95% CI) and P value for the likelihood of obstructive CAD for participants whose stress test did vs did not meet the trial-defined criteria is reported in addition to the ratio (95% CI) and P value of the sex-specific risk ratios (women vs men). In a sensitivity analysis, we analyzed only participants without evidence of prior infarction on the stress test.

A multivariate proportional odds model was created to assess the association between the extent of angina and the extent of ischemia and CAD jointly within the subset of patients who have not had antianginal medications changed in the last 3 months. The Seattle Angina Questionnaire frequency scale was grouped into the following categories: absent (score of 100), monthly (61-99), weekly (31-60), and daily (0-30). The model was adjusted for the following baseline clinical characteristics: age, sex, race/ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, prior myocardial infarction, estimated glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, and anti-anginal medical therapy. Age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and left ventricular ejection fraction were included as restricted cubic splines with knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles. P values were 2-sided, and the significance threshold was .05. Analysis began October 1, 2018.

Results

Among 2262 enrolled women and 6256 enrolled men, fewer women underwent CCTA (1524 of 2262 [67.4%] vs 4382 of 6256 [70.0%]; Table 1), but age was similar by sex. Women were more likely to have nonobstructive CAD (<50% stenosis in all vessels on CCTA) (353 of 1022 [34.4%] vs 378 of 3353 [11.3%]). The frequency of at least 50% stenosis was lower among women than men in every vessel (Table 1). Women were more likely than men to be excluded from randomization (odds ratio [95% CI] for randomization: 0.62 [0.55-0.69] after adjustment for age, race, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hypertension, diabetes, smoking status, prior myocardial infarction, qualifying stress test modality, and country of enrollment). The most common reasons for exclusion were insufficient ischemia in the opinion of the core laboratory and no obstructive CAD on study CCTA for both sexes (Table 1). Fewer enrolled women withdrew consent than enrolled men (66 of 1094 [6.0%] vs 195 of 2245 [8.7%]). However, among 5424 patients who were locally determined to be clinically eligible at sites completing screening logs, women were less likely to agree to participate (719 of 1552 women [46%] vs 2044 of 3872 men [53%]). A similar proportion of patients of both sexes were deemed by sites to be eligible for consent as recorded on the screening logs (1552 of 7277 women [21%] vs 3872 of 17 354 men [22%]. Clinical and stress test characteristics of enrolled participants by sex appear in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 1. CCTA Findings by Sex Among Enrolled Participants.

| Characteristic | Enrolled, No./total No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 2262) | Men (n = 6256) | ||

| Age at enrollment, median, (IQR), y | 64 (57-70) | 63 (56-69) | .10 |

| CCTA performed | 1524/2262 (67.4) | 4382/6256 (70.0) | .02 |

| CCTA findings | |||

| Vessels ≥50% stenosis by CCTA | |||

| 0 | 352/1022 (34.4) | 378/3353 (11.3) | <.001 |

| 1 | 200/1022 (19.6) | 585/3353 (17.4) | |

| 2 | 212/1022 (2.7) | 869/3353 (25.9) | |

| ≥3 | 258/1022 (25.2) | 1521/3353 (45.4) | |

| Specific native vessels with ≥50% stenosis by CCTA | |||

| LM | 59/1487 (4.0) | 442/4270 (1.4) | <.001 |

| LAD | 760/1342 (56.6) | 3133/4075 (76.9) | <.001 |

| Proximal LAD | 419/1461 (28.7) | 1829/4172 (43.8) | <.001 |

| LCx | 481/1265 (38.0) | 2408/3907 (61.6) | <.001 |

| RCA | 496/1218 (4.7) | 2348/3738 (62.8) | <.001 |

| Vessels ≥70% stenosis by CCTA | |||

| 0 | 452/915 (49.4) | 648/2878 (22.5) | <.001 |

| 1 | 240/915 (26.2) | 903/2878 (31.4) | |

| 2 | 137/915 (15.0) | 740/2878 (25.7) | |

| ≥3 | 86/915 (9.4) | 587/2878 (2.4) | |

| Specific native vessels with ≥70% stenosis by CCTA | |||

| LM | 16/1487 (1.1) | 93/4270 (2.2) | .007 |

| LAD | 464/1254 (37.0) | 2117/3842 (55.1) | <.001 |

| Proximal LAD | 171/1458 (11.7) | 901/4161 (21.7) | <.001 |

| LCx | 304/1221 (24.9) | 1606/3739 (43.0) | <.001 |

| RCA | 294/1158 (25.4) | 1609/3501 (46.0) | <.001 |

| Randomized | 1168/2262 (51.6) | 4011/6256 (64.1) | <.001 |

| Reasons for exclusion from randomizationa | |||

| Nonobstructive CAD on CCTA | 575/1094 (52.6) | 643/2245 (28.6) | <.001 |

| Insufficient ischemia | 465/1094 (42.5) | 885/2245 (39.4) | .09 |

| Unprotected left main ≥50 | 52/1094 (4.8) | 382/2245 (17.0) | <.001 |

| Withdrew consent | 66/1094 (6.0) | 195/2245 (8.7) | .007 |

| Intercurrent event | 10/1094 (.9) | 39/2245 (1.7) | .06 |

| Other | 142/1094 (13.1) | 454/2245 (21.9) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; IQR, interquartile range; LAD, left anterior descending; LM, left main; LCx, left circumflex; RCA, right coronary artery.

Note that reasons for exclusion are not mutually exclusive.

We next evaluated the association between ischemia severity and CCTA findings by sex. The likelihood of obstructive CAD was higher when the core laboratory confirmed trial-eligible ischemia than when the core laboratory did not agree with the site that ischemia was moderate or severe. There was no difference in this association by sex (ratio of sex-specific rate ratios of 50% stenosis 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92-1.16; Table 2). There was no such sex difference for any individual stress test modality. In every subgroup defined by sex, stress test modality and stress test results, men had a higher likelihood of obstructive CAD than women. In a sensitivity analysis excluding participants with evidence of prior infarction on the stress test, results were unchanged (data not shown).

Table 2. Likelihood of Obstructive CAD by Sex and Stress Test Findings, by Modality, in Enrolled Participants.

| Description | Proportion with ≥50% stenosis, No./total No. (%) | P value | Proportion with ≥70% stenosis, No./total No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||

| All stress modalities | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 774/1024 (75.6) | 3229/3455 (93.5) | <.001 | 597/923 (64.7) | 2771/3200 (86.6) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 155/257 (60.3) | 514/666 (77.2) | <.001 | 105/231 (45.5) | 381/600 (63.5) | <.001 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), yes/noc | 1.25 (1.13-1.39) | 1.21 (1.16-1.26) | 1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 1.42 (1.23-1.65) | 1.36 (1.28-1.45) | 1.04 (0.89-1.23) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | .55 | NA | NA | .61 |

| Stress imaging | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 572/751 (76.2) | 2278/2410 (94.5) | <.001 | 425/666 (63.8) | 1881/2195 (85.7) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 99/165 (60.0) | 319/427 (74.7) | <.001 | 58/144 (40.3) | 215/369 (58.3) | <.001 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), yes/noc | 1.27 (1.11-1.45) | 1.27 (1.20-1.34) | 1.00 (0.87-1.16) | 1.58 (1.29-1.95) | 1.47 (1.35-1.61) | 1.08 (0.86-1.35) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | .96 | NA | NA | .52 |

| Nonimaging | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 202/273 (74.0) | 951/1045 (91.0) | <.001 | 172/257 (66.9) | 890/1005 (88.6) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 56/92 (60.9) | 195/239 (81.6) | <.001 | 47/87 (54.0) | 166/231 (71.9) | .003 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), yes/noc | 1.22 (1.02-1.45) | 1.12 (1.05-1.19) | 1.09 (0.90-1.32) | 1.24 (1.00-1.53) | 1.23 (1.13-1.34) | 1.01 (0.80-1.26) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | .37 | NA | NA | .96 |

| Nuclear | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 326/373 (87.4) | 1482/1551 (95.6) | <.001 | 254/332 (76.5) | 1264/1434 (88.1) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 65/110 (59.1) | 227/312 (72.8) | .008 | 41/98 (41.8) | 151/268 (56.3) | .01 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), yes/noc | 1.48 (1.26-1.74) | 1.31 (1.23-1.41) | 1.13 (0.95-1.34) | 1.83 (1.44-2.33) | 1.56 (1.41-1.74) | 1.17 (0.90-1.52) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | .18 | NA | NA | .25 |

| Echo | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 206/330 (62.4) | 680/742 (91.6) | <.001 | 139/291 (47.8) | 515/652 (79.0) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 28/49 (57.1) | 82/102 (80.4) | .003 | 16/43 (37.2) | 58/89 (65.2) | .002 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), dyes/noc | 1.09 (0.85-1.41) | 1.14 (1.03-1.26) | 0.96 (0.73-1.26) | 1.28 (0.85-1.93) | 1.21 (1.04-1.42) | 1.06 (0.69-1.64) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | .76 | NA | NA | .80 |

| Echo (severe definition) | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 133/206 (64.6) | 472/509 (92.7) | <.001 | 87/180 (48.3) | 376/453 (83.0) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 101/173 (58.4) | 290/335 (86.6) | <.001 | 68/154 (44.2) | 197/288 (68.4) | <.001 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), yes/noc | 1.11 (0.94-1.30) | 1.07 (1.02-1.12) | 1.03 (0.87-1.22) | 1.09 (0.87-1.38) | 1.21 (1.11-1.33) | 0.90 (0.70-1.16) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | .71 | NA | NA | .42 |

| CMR | ||||||

| Meets criteriaa | 40/48 (83.3) | 116/117 (99.1) | <.001 | 32/43 (74.4) | 102/109 (93.6) | <.001 |

| Does not meet criteriab | 6/6 (100.0) | 10/13 (76.9) | .52 | 1/3 (33.3) | 6/12 (50.0) | >.99 |

| Ratio of proportions (95% CI), yes/noc | NA | NA | NA | 2.23 (0.45-11.17) | 1.87 (1.06-3.30) | 1.19 (0.22-6.58) |

| P valuec | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | .84 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CMR, stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not applicable.

Met trial-defined ischemia entry criteria according to the stress core laboratory for the respective stress test modality.

Did not meet trial-defined ischemia entry criteria according to the stress core laboratory for the respective stress test modality.

P value reported is for the comparison of the ratio of sex-specific rate ratios (women vs men) for assessing the likelihood of any obstructive CAD for participants who did vs did not meet trial-defined stress test criteria (moderate or severe ischemia for stress imaging, severe ischemia for nonimaging stress test, ie, exercise tolerance test).

Sex Differences Among Randomized Participants

In the randomized cohort including 1168 women and 4011 men, hypertension and diabetes were more common among women, and women were slightly older (Table 3). Randomized women were less likely to have a smoking history or have a history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting) but more likely to have prior history of heart failure.

Table 3. Randomized Participant Baseline Characteristics by Sex.

| Characteristic | Randomized, No./total No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 1168) | Men (n = 4011) | ||

| Age at randomization, median (IQR), y | 65 (59-71) | 64 (57-70) | .002 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 3/1154 (0.3) | 10/3975 (0.3) | .002 |

| Asian | 282/1154 (24.4) | 1203/3975 (30.3) | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 2/1154 (0.2) | 10/3975 (0.3) | |

| Black or African American | 57/1154 (4.9) | 147/3975 (3.7) | |

| White | 808/1154 (70.0) | 2595/3975 (65.3) | |

| Multiple races reported | 2/1154 (0.2) | 10/3975 (0.3) | |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity | 188/1091 (17.2) | 575/3724 (15.4) | .15 |

| Clinical history | |||

| Hypertension | 922/1164 (79.2) | 2867/3997 (71.7) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 522/1168 (44.7) | 1642/4011 (40.9) | .02 |

| Diabetes treatment | |||

| Insulin treated | 159/510 (31.2) | 333/1607 (20.7) | <.001 |

| Noninsulin diabetes medication | 290/510 (56.9) | 1065/1607 (66.3) | |

| None/diet controlled | 61/510 (12.0) | 209/1607 (13.0) | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 184/1165 (15.8) | 807/3997 (20.2) | <.001 |

| Cigarette smoking | |||

| Never | 756/1167 (64.8) | 1453/4007 (36.3) | <.001 |

| Former | 301/1167 (25.8) | 2025/4007 (50.5) | |

| Current | 110/1167 (9.4) | 529/4007 (13.2) | |

| Family history of premature coronary heart disease | 297/1016 (29.2) | 873/3474 (25.1) | .009 |

| Prior PCI | 189/1167 (16.2) | 861/4008 (21.5) | <.001 |

| CABG | 32/1168 (2.7) | 171/4011 (4.3) | .02 |

| MI, PCI, or CABG | 289/1165 (24.8) | 1281/3997 (32.0) | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter | 46/1166 (3.9) | 175/4007 (4.4) | .53 |

| Noncardiac vascular and comorbidity history | |||

| Prior carotid artery surgery or stent, stroke, or transient ischemic attack | 89/1166 (7.6) | 288/3999 (7.2) | .62 |

| Prior stroke | 40/1168 (3.4) | 111/4010 (2.8) | .24 |

| Heart failure history | |||

| Prior heart failure | 61/1168 (5.2) | 145/4011 (3.6) | .01 |

| Ejection fraction, No. | 1053 | 3584 | NA |

| Median (IQR) | 62 (58-68) | 60 (55-64) | <.001 |

| Type of stress test performed | |||

| Stress imaging | 924/1168 (79.1) | 2985/4011 (74.4) | .001 |

| Nuclear | 558/1168 (47.8) | 2009/4011 (50.1) | .16 |

| Echo | 291/1168 (24.9) | 794/4011 (19.8) | <.001 |

| CMR | 75/1168 (6.4) | 182/4011 (4.5) | .009 |

| ETT | 244/1168 (20.9) | 1026/4011 (25.6) | .001 |

| CCTA | 816/1168 (69.9) | 3097/4011 (77.2) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CCTA, coronary CT angiography; CMR, stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; ETT, Exercise Tolerance Test; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial Infarcation; NA, not applicable; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Women were more likely to undergo stress imaging (924 of 1168 women [79.1%] vs 2985 of men 4011 [74.4%]). Among participants who had stress imaging, women were less likely than men to undergo nuclear imaging and more likely to have echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (Table 3). Women randomized after stress imaging had lesser severity of ischemia than men, driven by differences in the subset of participants enrolled after nuclear stress testing (Table 4 and Figure). On nuclear imaging, women had lower summed difference scores than men (median [interquartile range], 8 [7-11] vs 9 [7-12]). Women were less likely to exhibit severe ischemia (166 of 555 [30%] vs 802 of 2000 [40%]), more likely to have moderate ischemia (283 of 555 [51.0%] vs 920 of 2000 [46.0%]) and more likely to have mild or no ischemia (57 of 555 [19%] vs 157 of 2000 [14%]). Ischemia severity as determined by stress echo was nearly the same for women and men (median [interquartile range], 4 [3-5] segments with stress-induced wall motion abnormalities; Table 4). Ischemia severity by stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was also similar between women and men, although numbers were lower. There were no sex differences in severity of ischemia on ETT in the randomized cohort (189 of 226 women [84%] vs 862 of 988 men [87%] with severe ischemia).

Table 4. Stress Test Results, Coronary Anatomy on CCTA, and Angina by Sex Among Randomized Participants.

| Characteristic | Randomized, No./total No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 1168) | Men (n = 4011) | ||

| Qualifying stress test core laboratory interpretation | |||

| Ischemia severity by imaging modality | |||

| Stress imaging (nuclear, echo or CMR) | |||

| Ischemia severity | |||

| Severe | 383/919 (41.7) | 1363/2972 (45.9) | .006 |

| Moderate | 386/919 (42.0) | 1215/2972 (40.9) | |

| Mild | 86/919 (9.4) | 232/2972 (7.8) | |

| None | 64/919 (7.0) | 162/2972 (5.5) | |

| Nuclear | |||

| Summed Difference Score, mean | 8.5 | 9.7 | <.001 |

| No. of infarcted segments, mean | 0.5 | 0.7 | .05 |

| Ischemia severity | |||

| Severe | 166/555 (29.9) | 802/2000 (4.1) | <.001 |

| Moderate | 283/555 (51.0) | 920/2000 (46.0) | |

| Mild | 57/555 (10.3) | 157/2000 (7.9) | |

| None | 49/555 (8.8) | 121/2000 (6.1) | |

| Pharmacologic only | 240/440 (54.5) | 491/1522 (32.3) | <.001 |

| Exercise only | 147/440 (33.4) | 837/1522 (55.0) | <.001 |

| Exercise and pharmacologic | 53/440 (12.0) | 194/1522 (12.7) | .70 |

| Echo | |||

| No. of segments, mean | |||

| Ischemic | 4.0 | 4.2 | .34 |

| Infarcted | 0.5 | 0.6 | .08 |

| Ischemia severity | |||

| Severe | 165/289 (57.1) | 461/790 (58.4) | .94 |

| Moderate | 88/289 (30.4) | 228/790 (28.9) | |

| Mild | 24/289 (8.3) | 64/790 (8.1) | |

| None | 12/289 (4.2) | 37/790 (4.7) | |

| Pharmacologic only | 70/245 (28.6) | 134/682 (19.6) | .004 |

| Exercise only | 172/245 (70.2) | 544/682 (79.8) | .002 |

| Exercise and pharmacologic | 3/245 (1.2) | 4/682 (0.6) | .39 |

| CMR | |||

| No. of segments, mean | |||

| With perfusion deficit | 8.6 | 8.7 | .92 |

| With perfusion deficit and infarct | 1.1 | 1.3 | .08 |

| Ischemia severity | |||

| Severe | 52/75 (69.3) | 100/182 (54.9) | .31 |

| Moderate | 15/75 (20.0) | 67/182 (36.8) | |

| Mild | 5/75 (6.7) | 11/182 (6.0) | |

| None | 3/75 (4.0) | 4/182 (2.2) | |

| Exercise tolerance test | |||

| Severity | |||

| Severe | 189/226 (83.6) | 862/988 (87.2) | .14 |

| Moderate | 22/226 (9.7) | 79/988 (8.0) | |

| Mild | 8/226 (3.5) | 26/988 (2.6) | |

| None | 7/226 (3.1) | 21/988 (2.1) | |

| CCTA findings | |||

| Any obstructive disease ≥50% stenosis by CCTA | 787/788 (99.9) | 3045/3048 (99.9) | >.99 |

| Multivessel disease ≥50% stenosis by CCTA | 479/664 (72.1) | 2200/2726 (80.7) | <.001 |

| Vessels ≥50% stenosis by CCTA | |||

| 0 | 1/568 (0.2) | 3/2418 (0.1) | <.001 |

| 1 | 178/568 (31.3) | 519/2418 (21.5) | |

| 2 | 184/568 (32.4) | 754/2418 (31.2) | |

| ≥3 | 205/568 (36.1) | 1142/2418 (47.2) | |

| Specific native vessels ≥50% stenosis by CCTA | |||

| LM | 4/798 (0.5) | 36/3047 (1.2) | .09 |

| LAD | 650/755 (86.1) | 2540/2922 (86.9) | .82 |

| Proximal LAD | 348/783 (44.4) | 1401/2956 (47.4) | .14 |

| LCx | 407/693 (58.7) | 1947/2802 (69.5) | <.001 |

| RCA | 414/667 (62.1) | 1897/2692 (7.5) | <.001 |

| Duke Prognostic Score | |||

| All vessels (LAD, LCX, RCA) <50% with fewer than 2 plaques 25%-49% or no proximal plaques 25%-49% | 1/568 (0.2) | 2/2420 (0.1) | <.001 |

| ≥2 Vessels with mild (25%-49%) plaque with at least 1 proximal plaque 25%-49% | 0/568 (0.0) | 1/2420 (0.0) | |

| 1 Vessel with at least moderate (≥50%) plaque | 45/568 (7.9) | 102/2420 (4.2) | |

| 2 Vessels with at least moderate (≥50%) plaque or 1 severe (≥70%) plaque | 110/568 (19.4) | 370/2420 (15.3) | |

| 3 Vessels with at least moderate (≥50%) plaque or 2 severe (≥70%) plaque or severe (≥70%) proximal LAD plaque | 225/568 (39.6) | 813/2420 (33.6) | |

| 3 Vessels with severe (≥70%) plaque or 2 severe (≥70%) plaque including proximal LAD | 183/568 (32.2) | 1096/2420 (45.3) | |

| LM ≥50% | 4/568 (0.7) | 36/2420 (1.5) | |

| Segment score, median (IQR) | |||

| Stenosis | 22 (16-27) | 25 (19-31) | <.001 |

| Involvement | 11 (8-13) | 12 (10-13) | <.001 |

| Angina history | |||

| Baseline Seattle Angina Questionnaire Angina Frequency Scale | |||

| Median (IQR) | 80 (70-100) | 90 (70-100) | <.001 |

| Daily angina (0-30) | 33/1156 (2.9) | 83/3954 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Weekly angina (31-60) | 249/1156 (21.5) | 746/3954 (18.9) | |

| Monthly angina (61-99) | 565/1156 (48.9) | 1678/3954 (42.4) | |

| No angina in past month (100) | 309/1156 (26.7) | 1447/3954 (36.6) | |

| Participant has ever had angina | 1068/1168 (91.4) | 3573/4011 (89.1) | .02 |

| Angina began or became more frequent over the past 3 mo | 329/1064 (30.9) | 1026/3564 (28.8) | .18 |

| Dyspnea status over the past montha | |||

| None | 670/1168 (57.4) | 2493/4011 (62.2) | <.001 |

| NYHA class I | 178/1168 (15.2) | 821/4011 (2.5) | |

| NYHA class II | 320/1168 (27.4) | 697/4011 (17.4) | |

| Rose Dyspnea Score | |||

| 0 | 304/1115 (27.3) | 1508/3785 (39.8) | <.001 |

| 1 | 381/1115 (34.2) | 1358/3785 (35.9) | |

| 2 | 204/1115 (18.3) | 553/3785 (14.6) | |

| 3 | 106/1115 (9.5) | 240/3785 (6.3) | |

| 4 | 120/1115 (10.8) | 126/3785 (3.3) | |

Abbreviations: CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CMR, stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; IQR, interquartile range; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex coronary artery; LM, left main; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RCA, right coronary artery.

There were no randomized participants in NYHA classes III-IV.

Figure. Sex Differences in Ischemia Severity, Atherosclerosis, and Angina Among Randomized ISCHEMIA Trial Participants.

Stress imaging includes stress nuclear, stress echocardiography, and stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Number of vessels diseased is shown based on the threshold of 50% stenosis. Frequency of angina is determined based on the Seattle Angina Questionnaire angina frequency scale, where 100 indicates no angina; 61 to 99, monthly angina; 31 to 60, weekly angina; and 0 to 30, daily angina. ETT indicates exercise tolerance test.

Women were less likely to undergo exercise stress testing and more likely to have pharmacologic stress testing. Women who exercised achieved a lower peak metabolic equivalent level than men but attained a higher percentage of the maximal predicted heart rate (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

On CCTA, women had a lesser extent of CAD compared with men, with more single-vessel disease and less multivessel disease, particularly 3-vessel CAD, among women (Table 4 and Figure). The prevalence of left anterior descending disease was similar between randomized women and men, but right CAD and circumflex CAD were less frequent among women (Table 4). Sex differences in CCTA findings among only those participants with core laboratory-confirmed moderate or severe ischemia are presented in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

In contrast with less extensive CAD among randomized women in the ISCHEMIA trial and less severe ischemia on stress imaging among women, randomized women had lower scores on the Seattle Angina Questionnaire angina frequency scale, indicating a greater burden of angina (Table 4). Fewer women reported that they were free of angina in the last month (309 of 1156 [27%] vs 1447 of 3954 [37%]). The higher severity of symptoms among women was also reflected in provider assessment via the New York Heart Association classification and in self-reported dyspnea (Table 4). On multivariate analysis including demographics, clinical characteristics, ischemia severity and CCTA findings, female sex was independently associated with greater angina frequency (odds ratio, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.13-1.76; P < .001).

Sex differences in medications at the time of randomization are presented in eTable 4 in the Supplement. Laboratory values and vital signs are shown in eTable 5 in the Supplement. Women had higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol at baseline and were less likely to be taking any statin, including high intensity statin.

Discussion

In this analysis of ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial participants, women had a greater burden of angina symptoms than men, despite having less extensive CAD. This extends prior observations to a cohort selected based on the combination of high-risk stress testing results and obstructive CAD on CCTA. Overall, randomized women had less core laboratory-confirmed severe ischemia on stress imaging compared with randomized men, with no difference by sex in the likelihood of having core laboratory-confirmed trial-eligible ischemia on ETT.

Our analysis is novel in that we report sex-specific results of stress testing, CCTA, and anginal symptoms in a large ischemic heart disease trial cohort. Although numerous studies have evaluated sex differences in the extent of CAD, fewer have considered sex differences after excluding patients with nonobstructive CAD, which is more common among women.19,20 The ISCHEMIA randomized cohort offers an ideal resource to address this question because patients with no obstructive CAD were excluded from randomization and because patients were selected for enrollment based on stress testing alone rather than coronary angiographic results. Our findings of less extensive CAD and more angina among randomized female ISCHEMIA participants are similar to findings from the COURAGE21 and BARI 2D2 trials and from those of a Mayo Clinic cohort study, all of which selected patients based on conventional invasive angiography alone.1 Our data provide important confirmation with a different perspective because in these prior studies, participants were selected clinically for angiography, while in ISCHEMIA, CCTA was performed as a routine to determine anatomic eligibility among participants with moderate or severe ischemia, with detailed results blinded to patients and physicians2,14,21 reducing referral and survival biases.

The association between angina symptoms, epicardial stenosis severity, and ischemia is complex and appears to differ by sex. Across the spectrum of ischemic heart disease severity, women who have angina report more severe symptoms than men, even when the extent of disease is the same.2,8,21,22 It has been hypothesized that women may have more diffuse disease leading to ischemia in the setting of less extensive CAD, but we found that women had fewer segments affected by plaque. Our findings may relate to a greater contribution of mental stress–induced ischemia and to greater sensing or reporting of ischemic symptoms among women. In the ACIP trial,23 women had a similar number and duration of ischemic episodes to men as detected by ambulatory electrocardiography despite less extensive CAD on angiography. Mental stress is more likely to elicit ischemia among women than men, and mental stress–induced ischemia is not related to CAD severity among women,24 while it is in men. Women rated pain as more intense than men during objectively assessed ischemia and had more nonpain symptoms.25 Lower endorphin levels among women with CAD correlate with more chest pain in daily life.26 A greater severity of coexisting microvascular coronary disease and/or endothelial dysfunction among women may theoretically have contributed to our findings. The greater burden of angina in women is important, not only because symptoms are important to patients but because registry data show that angina is a predictor of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction, independent of ischemia severity.27 The results of quality of life and outcomes in the ISCHEMIA trial by sex will be reported in the future.

Previous studies have shown that diagnostic accuracy of stress testing is lower among women than men when considering the reference standard of obstructive CAD. We confirm this in a cohort with moderate or severe ischemia but found no sex difference in the relative likelihood of obstructive CAD associated with more severe ischemia on stress testing.

The proportion of nonobstructive CAD based on CCTA findings, 34% among women and 11% among men, may be surprising given the requirement for a higher degree of ischemia on stress testing. However, this proportion is lower than in studies of invasive angiography to evaluate ischemia symptoms,28,29 and numerous studies have shown that true ischemia does occur in the setting of nonobstructive CAD.30 Unfortunately, we do not have data on angina symptoms in excluded participants. We believe that the requirement for moderate or severe ischemia is more likely to select for patients who have true ischemia, perhaps due to microvascular disease, but we cannot confirm this. Additional testing to confirm ischemia, such as coronary flow reserve testing, assessment of the index of microcirculatory resistance or nuclear mass spectroscopy, was not performed. The Changes in Ischemia and Angina (CIAO)–ISCHEMIA ancillary study (NCT02347215) enrolled patients with nonobstructive CAD on CCTA, evaluating changes in ischemia severity over time and how these changes relate to angina severity and the extent of nonobstructive atherosclerosis; CIAO enrolled a cohort that is nearly two-thirds female.

The proportion of randomized participants who are female (23%) is lower than the 35% we initially projected. This may be associated with the ischemia and CAD entry criteria. Our projection was likely too optimistic because the CLARIFY registry of stable ischemic heart disease patients included 23% women, and an analysis of appropriateness of revascularization included 25% women.22,31 These figures are very different from the 53% female cohort with potentially ischemic symptoms in the PROMISE trial32 of diagnostic testing because women are more likely to have negative tests than men. We worked closely with sites to maximize enrollment of eligible women in the trial. Women screened at sites were just as likely as men to be considered eligible for consent based on screening log data. Yet, a slightly lower proportion of women approached for consent agreed to participation. Once enrolled, women were slightly less likely to withdraw consent.

Limitations

Our analysis examined CAD severity as determined by CCTA, which was available in most participants. We recognize that CCTA results and invasive angiography findings may not be identical. Invasive angiography has been considered the reference standard for CAD severity, has the ability to assess collateral flow, and is the standard to which stress testing was originally compared. However, invasive angiography was not performed a priori for the trial in participants assigned to the conservative strategy. Fractional flow reserve can be derived from CCTA findings using proprietary software, but this was not available in the ISCHEMIA trial. Our analysis of the association between core laboratory confirmation of ischemia severity and atherosclerosis severity is limited by restriction to moderate or severe ischemia, so we were unable to report sensitivity or specificity of stress testing for obstructive CAD. We included 4 different stress testing modalities, which increases generalizability of trial results but limits our ability to detect sex differences for each of them. The steeper pressure-volume association in women and higher incidence of left ventricular hypertrophy have been implicated in increased symptoms in women with CAD, but we do not have access to measures of diastolic function parameters.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in the ISCHEMIA randomized trial population, identified on the basis of moderate or severe myocardial ischemia, women had more frequent angina, independent of their lesser extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis than men and less severe ischemia as assessed by independent core laboratories. These results suggest that factors other than epicardial obstructive CAD underlie the severity of symptoms in women.

eTable 1. Enrolled Participant Baseline Characteristics by Sex, including Stress Testing

eTable 2. Functional Capacity According to Imaging Modality by Sex among Randomized Participants

eTable 3. Extent of CAD by Sex among Enrolled Participants Undergoing Coronary CT Angiography with Core Lab-Verified Moderate-Severe Ischemia

eTable 4. Randomized Participant Baseline Medications by Sex

eTable 5. Vital Signs, Laboratory Values and Functional Status by Sex among Randomized Participants

eTable 6. Study Personnel

eTable 7. ISCHEMIA Committee, CCC, Trial-Related Personnel

References

- 1.Bell MR, Berger PB, Holmes DR Jr, Mullany CJ, Bailey KR, Gersh BJ. Referral for coronary artery revascularization procedures after diagnostic coronary angiography: evidence for gender bias? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(7):1650-1655. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00044-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamis-Holland JE, Lu J, Bittner V, et al. ; BARI 2D Study Group . Sex, clinical symptoms, and angiographic findings in patients with diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease (from the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation [BARI] 2 Diabetes trial). Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(7):980-985. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancini GB, Bates ER, Maron DJ, et al. ; COURAGE Trial Investigators and Coordinators . Quantitative results of baseline angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention in the COURAGE trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(4):320-327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.830091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiha J, Mitchell P, Gopinath B, Plant AJH, Kovoor P, Thiagalingam A. Gender differences in the severity and extent of coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2015;8:161-166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lansky AJ, Ng VG, Maehara A, et al. . Gender and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque composition, and clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(3)(suppl):S62-S72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CH, Koo BK, Lee JM, et al. . Influence of sex on relationship between total anatomical and physiologic disease burdens and their prognostic implications in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(5):e011002. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.011002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, et al. ; WISE Investigators . Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: part I: gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3)(suppl):S4-S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis KB, Chaitman B, Ryan T, Bittner V, Kennedy JW. Comparison of 15-year survival for men and women after initial medical or surgical treatment for coronary artery disease: a CASS registry study: Coronary Artery Surgery Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25(5):1000-1009. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00518-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, et al. ; WISE Investigators . Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3)(suppl):S21-S29. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaitman BR, Bourassa MG, Davis K, et al. . Angiographic prevalence of high-risk coronary artery disease in patient subsets (CASS). Circulation. 1981;64(2):360-367. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.64.2.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merz CN, Shaw LJ. Stable angina in women: lessons from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2011;12(2):85-87. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283430969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sara JD, Widmer RJ, Matsuzawa Y, Lennon RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prevalence of coronary microvascular dysfunction among patients with chest pain and nonobstructive coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(11):1445-1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong P, Pirozzolo G, Athanasiadis A, Sechtem U. Epicardial coronary spasm in women with angina pectoris and unobstructed coronary arteries is linked with a positive family history: an observational study. Clin Ther. 2018;40(9):1584-1590. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maron DJ, Hochman JS, O’Brien SM, et al. ; ISCHEMIA Trial Research Group . International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial: rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2018;201:124-135. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, et al. ; ISCHEMIA Research Group . Baseline characteristics and risk profiles of participants in the ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):273-286. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, et al. ; ISCHEMIA Research Group . Baseline characteristics and risk profiles of participants in the ISCHEMIA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):273-286. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Picard MH, et al. ; National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored ISCHEMIA Trial Investigators . Comparative definitions for moderate-severe ischemia in stress nuclear, echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(6):593-604. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, et al. . Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(12):1161-1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epps KC, Holper EM, Selzer F, et al. . Sex differences in outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention according to age. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(2)(suppl 1):S16-S25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan EL, Farrell LS, Walford G, et al. . The New York State risk score for predicting in-hospital/30-day mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(6):614-622. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acharjee S, Teo KK, Jacobs AK, et al. ; COURAGE Trial Research Group . Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention in women with stable coronary disease: a pre-specified subset analysis of the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive druG Evaluation (COURAGE) trial. Am Heart J. 2016;173:108-117. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari R, Abergel H, Ford I, et al. ; CLARIFY Investigators . Gender- and age-related differences in clinical presentation and management of outpatients with stable coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(6):2938-2943. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frishman WH, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hirsch H, et al. . Differences between male and female patients with regard to baseline demographics and clinical outcomes in the Asymptomatic Cardiac Ischemia Pilot (ACIP) Trial. Clin Cardiol. 1998;21(3):184-190. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960210310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almuwaqqat Z, Sullivan S, Hammadah M, et al. . Sex-specific association between coronary artery disease severity and myocardial ischemia induced by mental stress. Psychosom Med. 2019;81(1):57-66. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Antono B, Dupuis G, Fortin C, Arsenault A, Burelle D. Angina symptoms in men and women with stable coronary artery disease and evidence of exercise-induced myocardial perfusion defects. Am Heart J. 2006;151(4):813-819. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheps DS, Kaufmann PG, Sheffield D, et al. . Sex differences in chest pain in patients with documented coronary artery disease and exercise-induced ischemia: results from the PIMI study. Am Heart J. 2001;142(5):864-871. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.119133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steg PG, Greenlaw N, Tendera M, et al. ; Prospective Observational Longitudinal Registry of Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease (CLARIFY) Investigators . Prevalence of anginal symptoms and myocardial ischemia and their effect on clinical outcomes in outpatients with stable coronary artery disease: data from the International Observational CLARIFY Registry. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1651-1659. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maddox TM, Stanislawski MA, Grunwald GK, et al. . Nonobstructive coronary artery disease and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2014;312(17):1754-1763. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jespersen L, Hvelplund A, Abildstrøm SZ, et al. . Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(6):734-744. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Walsh MN, Fleg JL. Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (INOCA): developing evidence-based therapies and research agenda for the next decade. Circulation. 2017;135(11):1075-1092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko DT, Guo H, Wijeysundera HC, et al. ; Cardiac Care Network (CCN) of Ontario Variations in Revascularization Practice in Ontario (VRPO) Working Group . Assessing the association of appropriateness of coronary revascularization and clinical outcomes for patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(19):1876-1884. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemal K, Pagidipati NJ, Coles A, et al. . Sex differences in demographics, risk factors, presentation, and noninvasive testing in stable outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease: insights from the PROMISE trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(4):337-346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Enrolled Participant Baseline Characteristics by Sex, including Stress Testing

eTable 2. Functional Capacity According to Imaging Modality by Sex among Randomized Participants

eTable 3. Extent of CAD by Sex among Enrolled Participants Undergoing Coronary CT Angiography with Core Lab-Verified Moderate-Severe Ischemia

eTable 4. Randomized Participant Baseline Medications by Sex

eTable 5. Vital Signs, Laboratory Values and Functional Status by Sex among Randomized Participants

eTable 6. Study Personnel

eTable 7. ISCHEMIA Committee, CCC, Trial-Related Personnel