Abstract

A systemic disease of domestic ferrets characterized by pyogranulomatous inflammation was first recognized in Europe and the United States in 2002. The disease closely resembled feline infectious peritonitis and subsequently has been shown to be associated with ferret systemic coronavirus (FRSCV). A definitive laboratory diagnosis of this disease is typically based on a combination of immunohistochemistry (IHC) and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction tests to detect FRSCV in granulomatous lesions. In 2010, this feline infectious peritonitis–like disease was first identified in a laboratory ferret in Japan, and laboratory confirmation of the clinical diagnosis was limited to IHC. This report describes 2 cases of systemic coronavirus-associated disease in ferrets presented to Japanese veterinary hospitals. Both presented with pyogranulomatous inflammation in the abdominal cavity, and both cases tested positive for coronavirus antigen by IHC. In 1 case, for which unfixed tissues were available, FRSCV RNA was detected by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in the affected tissues.

Key words: coronavirus disease, ferret, FIP, Japan, pyogranulomatous inflammation

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is a fatal, multisystemic, immune-mediated disease of cats caused by a feline coronavirus mutant, generally considered to arise spontaneously from subclinical low-pathogenic or nonpathogenic feline enteric coronavirus.1 Recently, another hypothesis was presented,2 which states that genetically distinct avirulent and virulent forms of feline coronavirus cocirculate in natural cat populations. In ferrets, epizootic catarrhal enteritis, caused by the ferret enteric coronavirus (FRECV), is widely recognized.3, 4 More recently, a new ferret systemic coronavirus (FRSCV)-associated ferret disease, closely resembling the granulomatous or dry form of FIP, was reported in the United States, Europe, and Japan.5, 6, 7 Although it is unknown whether FRSCV and FRECV are genetically distinct coronaviruses of ferrets, 3 geographically distinct systemic ferret coronavirus strains were found to share a conserved spike (S) gene genotype that was distinguishable from that of 3 independent enteric coronavirus strains.8 Based on this finding, 2 S gene genotype-specific reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays had been developed that can potentially differentiate FRSCV from FRECV.8 The authors were recently involved with 2 ferret cases that were presented to private veterinary practices with clinical signs consistent with FIP-like disease. All confirmatory testing by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and RT-PCR was conducted at the Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health at Michigan State University (Lansing, MI USA) using the previously described methods.3, 4, 8

Case 1

A 15-month-old castrated male domestic ferret weighing 840 g was admitted to the Ouji Pet Clinic (Tokyo, Japan) for evaluation of significant weight loss. The ferret also exhibited alopecia in the tail region, anorexia, ataxia, and paresis of all 4 limbs. Blood glucose concentration was within reference ranges (78 mg/dL, reference limits: 69 to 139 mg/dL). During an ultrasonographic examination of the abdominal cavity, a mass (10 mm in diameter) was identified. Enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg orally, twice a day, Baytril; Bayer HealthCare, Manheim, Germany), prednisolone (1 mg/kg POq 12 h) (Predonine Tablets 5 mg, Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), and B-complex vitamins were prescribed. An improvement in the ferret’s appetite was observed during the 12-week course of treatment. The ferret died 135 days after the initial visit. At necropsy, white nodules, ranging from 5 to 10 mm in diameter and dispersed over the serosal surface of all lung lobes, were detected. Enlargement of the adrenal glands and granulomatous lesions around the enlarged mesenteric lymph node were also present. There were no remarkable gross changes in the brain. Histopathologically, multifocal granulomatous inflammatory lesions, consisting of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, were observed in the lung, adrenal gland, intestinal tract ( Fig. 1), mesenteric lymph node, and meninges of the brain. Immunohistochemical analyses of tissues were performed using the antialphacoronavirus monoclonal antibody, FCV3-70a, as previously described.3, 9 Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated the presence of coronavirus antigens in the mesentery. RT-PCR testing was not performed because unfixed tissues were not available. The formalin-fixed tissue samples for this case had undergone overfixation (>48 hours in formalin) and were no longer suitable for RT-PCR testing. Mycobacteriosis was not observed with Ziehl-Neelsen or Periodic acid-Schiff stains.

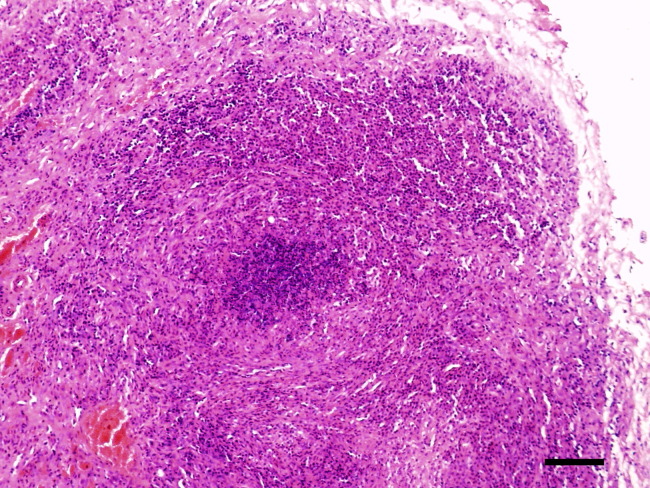

Figure 1.

Small intestine of a ferret with confirmed ferret systemic coronavirus infection. Note multifocal granulomatous inflammation consisting of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Bar = 300 μm. H&E stain. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Case 2

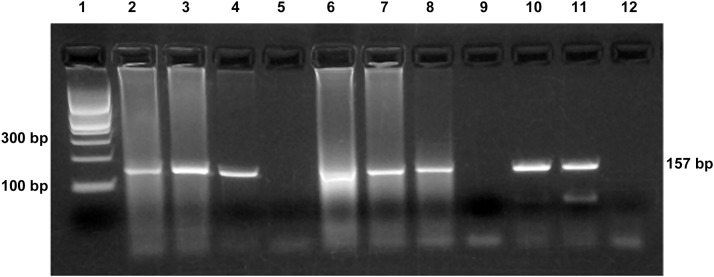

A 20-month-old spayed female ferret, weighing 540 g, was presented for evaluation of significant weight loss and anorexia. A physical examination revealed the presence of an abdominal mass, which was 30 mm in diameter. Abnormal results from the complete blood count and plasma biochemistry panel indicated leukocytosis (14,900 per µL, reference limits: 3500 to 7000 per µL), hyperglycemia (221 mg/dL, reference limits: 69 to 139 mg/dL), elevated aspartate amino transferase (323 U/L, reference limits: 38 to 89 U/L), hyperproteinemia (12.0 g/dL, reference limits: 5.1 to 7.8 g/dL), and hyperglobulinemia (60.2%, A/G = 0.28). Aleutian disease (AD) virus (ADV)-specific antibody titers were negative. An abdominal ultrasonography examination revealed a hypoechoic abdominal mass measuring 33.2 × 19.4 mm2, with significant blood flow. An ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the mass was collected. The results revealed pyogranulomatous inflammation, consisting of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. On day 1, enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg, orally, twice a day) and prednisolone (1 mg/kg, orally, once a day) were prescribed. No improvement was noted, and an exploratory laparotomy was performed on day 7. Granulomatous lesions of the intestinal tract, mesentery, mesenteric lymph node, spleen, and retroperitoneum were found. Histopathologically, multifocal granulomatous inflammatory lesions consisting of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes were observed in the mesentery and greater omentum. Mycobacteriosis was not detected with Ziehl-Neelsen or Periodic acid-Schiff stains. After surgery, prednisolone was increased to 2 mg/kg by mouth once a day and enrofloxacin increased to 10 mg/kg by mouth once a day. On day 24, the ferret showed an improved appetite, and an abdominal ultrasonography examination revealed a reduced abdominal mass, now 22.2 × 12.0 mm2. On day 50, the mass could not be detected by palpation. Although the animal’s overall condition continued to decline 150 days following the initial presentation, the patient continued to have a good appetite. However, 428 days following the initial presentation, the ferret died from severe respiratory distress. At necropsy, there were no granulomatous lesions around the mesenteric lymph node. White nodules were found to be dispersed over the serosal surfaces of all lung lobes ( Fig. 2), and diffuse white lesions were also found on the serosal surfaces of the spleen, liver, kidney, intestine, and within the meninges. Histologically, these lesions were characterized by multifocal pyogranulomatous perivasculitis ( Fig. 3). IHC revealed the presence of coronavirus antigen in the intestinal tract ( Fig. 4), lungs, and brain. Histopathologically, the architecture of the mesenteric lymph node, spleen, and kidneys was replaced by diffuse infiltration of malignant lymphocytes, indicative of lymphoma. The intestinal tract and brain did not reveal any evidence of lymphoma. RT-PCR testing using FRSCV genotype-specific primers8 was performed on unfixed tissue samples. FRSCV RNA was detected in the intestinal tract, mesentery, and brain (Fig. 4). The samples were also tested by the FRECV genotype-specific RT-PCR assay8 and were found to have positive results ( Fig. 5). Hence, the ferret coronavirus detected from case 2 bears the S gene genotype consistent with that of a systemic pathotype observed in a previous study.8

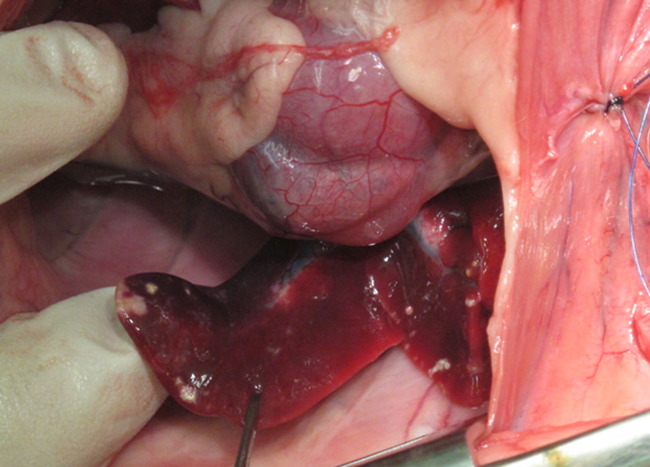

Figure 2.

Gross necropsy of a ferret with FRSCV infection. Note lung lobes with white nodules ranging from 5 to 10 mm in diameter dispersed over serosal surface.

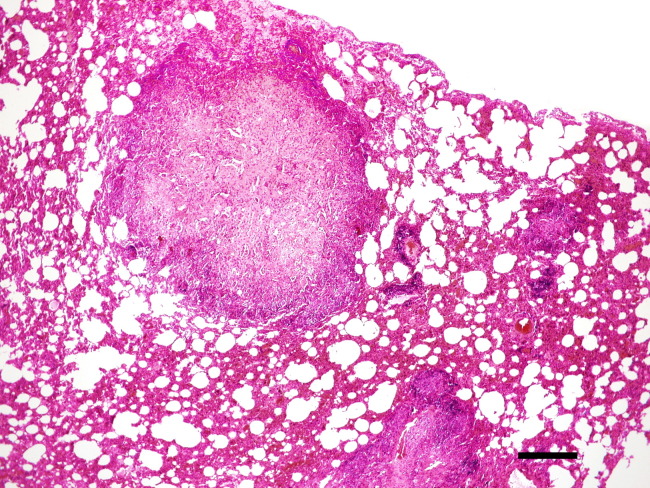

Figure 3.

Lung of a ferret with confirmed FRSCV infection. Note multifocal pyogranulomatous inflammation consisting of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Bar=800 μm. H&E stain. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

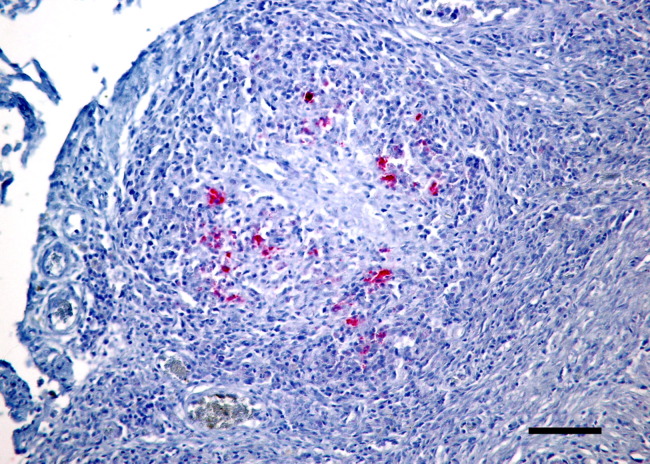

Figure 4.

Small intestine of a ferret with confirmed FRSCV infection. Note pyogranulomatous peritonitis and positive labeling of macrophages (red) with antibody directed against alphacoronavirus antigen. Alkaline phosphatase red chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain, Bar = 200 μm.

Figure 5.

FRSCV RT-PCR. Lanes: (1) 100 bp DNA ladder; (2) small intestine; (3) mesentery; (4) brain; (5) negative extraction control; (6) small intestine; (7) mesentery; (8) brain; (9) negative extraction control; (10 and 11) FRSCV-positive RNA; and (12) negative template control (water).

Discussion

FRSCV-associated disease has mostly been reported in ferrets <18 months of age.5 Clinical signs are nonspecific, including diarrhea, weight loss, anorexia, and vomiting. Signs of central nervous system disease include ataxia and tremors. On abdominal palpation, the presence of large abdominal masses is a common finding. Typical hematologic signs include nonregenerative anemia, hyperglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and thrombocytopenia. Serum protein electrophoresis shows a polyclonal gammopathy.5, 10 Biochemical changes are variable and reflect damage to abdominal organs. Serum chemistry abnormalities include elevated serum lipase, elevated blood urea nitrogen, elevated serum alanine transferase, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and elevated serum gamma-glutamyl transferase.5, 10, 11 The 2 cases presented in this report involved a 15- and a 20-month-old ferret. Both showed weight loss, anorexia, and had palpable abdominal masses. Case 1 presented with ataxia. Case 2 had leukocytosis, hyperglycemia, elevated serum alanine transferase, hyperproteinemia, and hypergammaglobulinemia. Gross lesions observed in ferrets with FRSCV infection closely resemble those described in cats with the dry form of FIP. The most commonly observed gross lesion consists of multifocal to coalescing white to tan irregular nodules or plaques dispersed over serosal surfaces of the mesentery, mesenteric lymph node, liver, kidney, spleen, and lung.5, 10 Histologic lesions are characterized by severe FIP-like pyogranulomatous inflammation and are most commonly observed in the mesentery and along the peritoneal surface.5, 10 In the cases presented here, granulomatous inflammation was detected histologically in the lung, adrenal gland, intestinal tract, mesenteric lymph node, and meninges of the brain in case 1, and in the lung, spleen, liver, kidney, intestine, mesentery, greater omentum, and meninges of the brain in case 2. IHC and RT-PCR are the tests of choice to demonstrate the presence of coronavirus antigen and RNA, respectively, in affected tissues. Coronavirus antigens were detected in the mesentery of case 1 and in the intestinal tract, lung, and brain of case 2. In case 2, FRSCV RNA was detected in unfixed tissue RNA extracts of the intestinal tract, mesentery, and brain by RT-PCR. This is the first case of FRSCV-associated disease in Japan confirmed by RT-PCR testing. Efficient detection of FRSCV by RT-PCR depends on the quality of RNA extracted from the samples. It is known that fixation of tissues in formalin results in RNA damage that compromises the efficiency of reverse transcription.12 Therefore, it is best to collect unfixed tissue samples if RT-PCR is to be used for confirmatory diagnosis. Moreover, it is also important to note that even fresh tissue needs to be handled appropriately to preserve the RNA. This can be accomplished by placing the tissue in RNAlater (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA USA) or by snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. Antemortem diagnosis of FRSCV-associated disease may be difficult, as laparotomy and biopsy can be risky in compromised patients.

The differential diagnosis for polyclonal gammopathy in domestic ferrets includes AD.5, 10 AD is caused by a parvovirus and affects a ferret’s immune system. Multiple organs are damaged by antigen/antibody complexes, lymphocytes, and plasmacytes, leading to clinical signs (e.g., anorexia, weight loss, and abdominal masses). AD exhibits a similar pathophysiology to that of FRSCV-associated disease.4, 11, 13 Blood testing reveals hypergammaglobulinemia and elevated serum ADV antibody titers. Case 2 was negative for ADV-specific antibodies. The ADV-specific antibody test could not be performed for case 1. AD cases in which viral antibody titers did not become elevated have been reported.14 To better differentiate FRSCV-associated disease from AD, histopathological examination may be required.

Currently, no cure exists for FRSCV infection; most animals die of the disease or are humanely euthanized. Nonetheless, some ferrets have survived for several months to more than a year after diagnosis with supportive care.5, 10 FRSCV-associated disease is immune mediated. Treatment, therefore, is aimed at suppressing the immune system, thus abating the excessive inflammatory response. In addition, supportive care is required to improve the ferret’s quality of life.15 For the ferret described in case 2, FRSCV-associated disease improved over time and at necropsy; the granulomatous inflammation around the mesenteric lymph node had cleared. It is possible that the high-dose prednisolone treatment had a positive clinical effect on the FRSCV-associated disease. Concurrent lymphoma may have contributed to death in this case. In case 1, prednisolone may have resulted in an improved appetite. A recent review on FRSCV-associated disease recommends the use of prednisolone for potent immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects, which may help stimulate the ferret’s appetite and ameliorate clinical disease signs.11

Ferrets exhibiting the clinical disease signs described in this report are relatively common case presentations to veterinary clinics located in Japan. Many cases of suspected mycobacteriosis or AD could have actually been systemic coronavirus infections. In fact, FRSCV-associated disease may have already been present and widespread in the country before official recognition.

References

- 1.Chang H.W., de Groot R.J., Egberink H.F. Feline infectious peritonitis: insights into feline coronavirus pathobiogenesis and epidemiology based on genetic analysis of the viral 3c gene. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 2):415–420. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown M.A., Troyer J.L., Pecon-Slattery J. Genetics and pathogenesis of feline infectious peritonitis virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1445–1452. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.081573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams B.H., Kiupel M., West K.H. Coronavirus-associated epizootic catarrhal enteritis in ferrets. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;217(4):526–530. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise A.G., Kiupel M., Maes R.K. Molecular characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE) in ferrets. Virology. 2006;349:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garner M.M., Ramsell K., Morera N. Clinicopathologic features of a systemic coronavirus-associated disease resembling feline infectious peritonitis in the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius) Vet Pathol. 2006;45:236–246. doi: 10.1354/vp.45-2-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez J., Ramis A.J., Reincher M. Detection of feline infectious peritonitis virus-like antigen in ferrets. Vet Rec. 2006;158:523. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.15.523-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michimae Y., Mikami S., Okimoto K. The first case of feline infectious peritonitis-like pyogranuloma in a ferret infected by coronavirus in Japan. J Toxicol Pathol. 2010;23(2):99–101. doi: 10.1293/tox.23.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise A.G., Kiupel M., Garner M.M. Comparative sequence analysis of the distal one-third of the genomes of a systemic and an enteric ferret coronavirus. Virus Res. 2010;149(1):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons F.A., Vennema H., Rofina J.E. A mRNA PCR for the diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis. J Virol Methods. 2005;124(1-2):111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perpiñán D., López C. Clinical aspects of systemic granulomatous inflammatory syndrome in ferrets (Mustela putorius furo) Vet Rec 9. 2008;162(6):180–184. doi: 10.1136/vr.162.6.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray J., Kiupel M., Maes R.K. Ferret coronavirus-associated diseases. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2010;13(3):543–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung J.Y., Braunschweig T., Williams R. Factors in tissue handling and processing that impact RNA obtained from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56(11):1033–1042. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.951863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James G.F., Pearson R.C., Gorham J.R. Normal clinical and biologic parameters. In: James G.F., editor. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. ed 2. Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 1998. pp. 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chikako K., Miho T., Tomoko H. Twelve ferrets with hyperproteinemia suggesting Aleutian disease. Hiroshima J Vet Med. 2006;21:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrie J.-P., Morrisey J.K. Cardiovascular and other diseases. In: Quesenberry K.E., Carpenter J.W., editors. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents, Clinical Medicine and Surgery. ed 2. Saunders/Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA: 2003. pp. 66–68. [Google Scholar]