Abstract

Background

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) has been used to support the growth and proliferation of mammalian cells for decades. Owing to several risk factors associated with FBS, several trials have been conducted to evaluate substitutes to FBS with the same efficiency and the lower risk issues.

Methods

In this study, human platelet lysate (HPL) derived from activated human platelets was evaluated as an alternative to FBS due to the associated risk factors. To evaluate the efficiency of the preparation process, platelet count was performed before and after activation. The concentrations of several growth factors and proteins were measured to investigate HPL efficiency. HPL stability was studied at regular intervals, and optimal heparin concentration required to prevent gel formation in various media was determined. The biological activity of HPL and FBS was compared by evaluating the growth performance of Vero and Hep-2 cell lines.

Results

Result of platelet count assay revealed the efficiency of HPL preparation process. Growth factor concentrations in HPL were significantly higher than those in FBS, while the protein content of HPL was lower than that of FBS. Stability study data showed that the prepared HPL was stable for up to 15 months at −20℃. Ideal heparin concentration to be used in different media was dependent on calcium concentration. Results of cell viability assay showed that HPL was superior to FBS in supporting the growth and proliferation of Vero and Hep-2 cells.

Conclusion

The HPL prepared by the mechanical activation of platelets may serve as an efficient alternative to FBS in cell culture process.

Keywords: Vero cell line, Hep-2 cell line, Heparin, Human platelet lysate, Growth factors, Viability assay

INTRODUCTION

Cell culture is a routine laboratory technique essential for the study of physiological and biochemical processes. It facilitates quality control testing by serving as an alternative to animal models. Further, it is useful for the synthesis of valuable biological products, including specific proteins, vaccines, or viruses, that require mammalian cells for propagation [1].

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) is normally added to culture media to support the growth and proliferation of various cell lines, including Hep-2 and Vero cells. Although FBS is a valuable supplement enriched with nutrients such as hormones, plasma proteins, growth factors, fibronectin, and laminin, the associated risk factors have raised awareness to stop its use as a growth supplement in cell culture media [2].

Vero and Hep-2 cell lines are excellent models for several applications. Vero cells are used for the production of vaccines such as inactivated polio virus, rotavirus, and smallpox vaccines [3,4], and have been employed in virology studies for the titration of measles and mumps viruses [5] and propagation of rabies virus [6]. Hep-2 cells are one of the most important cell types widely used in quality control testing, especially for oral poliomyelitis vaccine [7], and are a part of other medical analysis and autoimmune diagnostics such as anti-nuclear antibody screening tests [8].

Considering the applicability of these cell lines, it is imperative to develop a suitable alternative to FBS to avoid the drawbacks associated with the use of animal serum in Vero and Hep-2 cell cultures. Many studies have been conducted to evaluate human platelet lysate (HPL) for in vitro cultures of endothelial, fibroblast, and tumor cell lines as well as for regenerative cells such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [9].

The HPL obtained from the activation of human platelets, either chemically using calcium chloride (CaCl2) and thrombin or mechanically by freeze/thaw cycles, is rich in several nutrients that promote cell growth and proliferation. Attachment factors (vitronectin and fibronectin) and several growth factors such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) present in platelets are released upon their activation [10].

HPL can support the growth and proliferation of cells in culture, as platelets are known to play a vital role in tissue renewal and wound healing. Activated platelets aggregate and degranulate after tissue injury to initiate primary hemostasis. The release of growth factors from these activated platelets induces inflammation and smooth muscle and fibroblast cell activation along with collagen synthesis and angiogenesis, resulting in epithelialization and tissue regeneration [11].

Based on the previous reports, here we evaluate the HPL prepared by freeze/thaw cycles as an alternative to FBS to support the growth and proliferation of Vero and Hep-2 cell lines by performing platelet counts before and after activation. We measure growth factor and protein concentrations in both samples and study the stability of growth factors in HPL and FBS for a long period. In addition, we determine the ideal concentration of heparin essential to prevent gel formation in HPL culture media. We also study the biological effect of HPL on Vero and Hep-2 cell cultures using 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and cell count assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of human platelet lysate

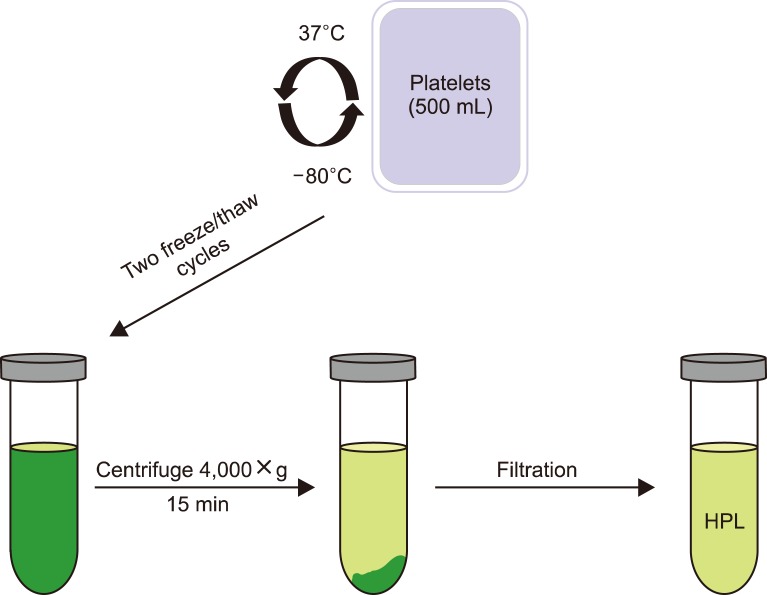

Freshly prepared filtered platelets (#E400116) collected from different individuals of blood group (O−) were obtained from the National Blood Transfusion Center of Egypt (NBTC). These platelets (500 mL) at the platelet-rich plasma (PRP) stage were stored at −80℃ until further processing. After 24 hr, the frozen PRP was incubated at 37℃ until it was completely thawed. The sudden increase in temperature results in platelet activation and release of growth factors in the solution (first cycle). To obtain high concentrations of growth factors, a second freeze/thaw cycle was performed. Centrifugation was carried out at 4,000×g for 15 min at 4℃ to remove platelet particles and membrane fragments, which may produce aggregates in cell culture media due to platelet lysis. The sediment was discarded, while the supernatant (450 mL) was collected, filter sterilized, and stored at −20℃ as the prepared HPL until further use (Fig. 1) [9].

Fig. 1. Preparation of human platelet lysate from PRP.

Platelet count test

Platelet count test was performed twice, first at the PRP stage and then after the completion of the activation step using KX-21 Automated Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) to determine the efficiency of the activation process.

Measurement of growth factors in HPL and FBS samples

For HPL and FBS (#S1810-100, Biowest, Riverside, MO, USA) samples, the concentrations of IGF-1 and TGF-β1 were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits #IGF31-K01 (Eagle Biosciences, Inc., Amherst, NH, USA) and #SK00033-02 (Aviscera Bioscience Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), respectively. In addition, the concentration of VEGF was assayed using #SK00122 (Aviscera Bioscience Inc.) and #MBS935379 (Mybiosource, San Diego, CA, USA) kit for HPL and FBS, respectively, while that of EGF was measured using #ELH-EGF (RayBiotech, Inc., Peachtree Corners, GA, USA) and #MBS005514 (Mybiosource) kits, respectively.

FGF and PDGF concentrations were assayed in HPL samples using ELH-FGF9 and ELH-PDGFAA kits (RayBiotech, Inc.), respectively, and in FBS samples using EK0348-BV (Boster Biological Technology, Pleasanton, CA, USA) and CSB-EL017708BO (Cusabio, Houston, TX, USA) kits, respectively.

Measurement of protein content in HPL and FBS samples

Protein content of FBS and HPL samples was measured using the Bradford protein assay kit (#SK3041, Bio Basic Inc, Markham, ON, Canada).

Optimal concentration of heparin in medium with HPL

Serial dilutions of heparin (#07980, Stem Cell, Vancouver, BC, Canada) form 1 to 0.0625 IU/mL were prepared and added to Medium 199 with Earl's salt (#F0615, Biochrom GmbH, Berlin, Germany), MEM Earl's (#Al260A, HiMedia, Kelton, PA, USA), MEM Hank's (#Al075A, HiMedia), Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 (#SR273, Serox GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH=7.4 (#PD0435, Bio basic Inc.), and normal saline (#213-500, Otsuka, Egypt). HPL was added to each dilution at a final concentration of 10%. Negative control tubes included cell culture media only, while positive control tubes contained cell culture media supplemented with 10% HPL. Three tubes from each dilution were incubated at different temperatures (4℃, 37℃, and room temperature) for 24 hr and then examined for hydrogel formation.

Calcium concentration and coagulation

Serial dilution of CaCl2 (#223506, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) from 2 to 0.125 mM were prepared and added to deionized water containing 10% HPL. Three tubes from each dilution were incubated at different temperatures (4℃, 37℃, and room temperature) for 24 hr before analysis for coagulation.

Growth factor stability in HPL and FBS

To compare the stability of the prepared HPL with that of FBS, the concentrations of different growth factors such as IGF-1, TGF-β1, and VEGF in HPL and FBS samples stored at −20℃ were measured over 15 months.

Cell viability assay

MTT reduction assay

Vero cells from group A were cultivated in Medium 199 with Earl's salt containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (#L0022-20, Biowest), while those from group B were grown in Medium 199 with Earl's salt containing 10% HPL, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.25 IU/mL heparin. Group C cells were cultured as group B cells except that 10% HPL was replaced with 5% HPL. Group D cells were cultivated in a serum-free medium (SFM) (group A medium without FBS). All groups were incubated at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Hep-2 cells from group A were grown in MEM Earl's media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin, while those from group B were cultivated in MEM Earl's media containing 10% HPL, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.25 IU/mL heparin. The cells from group C were cultured in group B medium containing 5% instead of 10% HPL. Group D cells were cultured in MEM Earl's medium without FBS (SFM). All groups were incubated in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37℃.

The MTT solution was prepared by dissolving the MTT powder (M2003, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS (pH=7.4) at 5 mg/mL concentration and incubated with cells for 3 hr at 37℃. After incubation, dimethyl sulfoxide (#67-68-5, Oxford, Palghar, India) was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals by incubating the plates at 37℃ for 30 min, followed by absorbance measurement using Multimode ELISA reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 570 nm wavelength [12].

Cell counting assay

Vero cells were cultured in 25 cm2 cell culture flasks using Medium 199 with Earl's salt, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for group A and Medium 199 with Earl's salt, 10% HPL, 0.25 IU/mL heparin, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for group B and then incubated at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Hep-2 Cells were seeded in 25 cm2 cell culture flasks using MEM Earl's media, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin for group A and MEM Earl's media, 10% HPL, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin for group B and incubated in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37℃.

Cells were detached using trypsin ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; #BE17-161E, Lonza, Belgium) on day 2 and 5, mixed (1:1) with trypan blue (#L0990-100, Biowest), and counted using Invitrogen Countess II Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) [13].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.03 software; two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), repeated measures ANOVA, and t-test were applied as appropriate. A value of P <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Platelet count

The platelet count at the PRP stage before platelet activation was 1.02×106/µL, which greatly decreased to 1×103/µL at the HPL stage after platelet activation.

Concentrations of growth factors

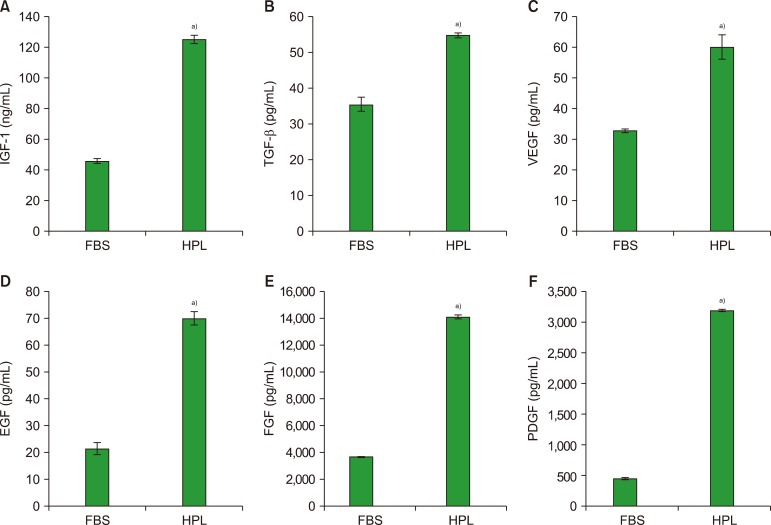

The results shown in Fig. 2 indicate that the level of IGF-1 in HPL (125±2.6 ng/mL) was approximately three-fold higher than that in FBS (46±1.6 ng/mL) (P <0.05), while TGF-β1 and VEGF levels in HPL (55±0.6 and 60±4 pg/mL, respectively) were also significantly higher than those in FBS (35.6±1.9 and 33±0.6 pg/mL, respectively) (P <0.05). The concentrations of PDGF, EGF, and FGF were significantly higher (approximately four-fold or higher) in HPL samples (3,193±16, 70±2.4, and 14,134±142 pg/mL, respectively) than in FBS (449±16, 21.5±2.2, and 3,697±6.7 pg/mL, respectively) (P <0.05).

Fig. 2. Growth factor contents in FBS and HPL samples. IGF-1 (A), TGF-β (B), VEGF (C), EGF (D), FGF (E), PDGF (F). Values are expressed as means±SD (N=3).

a)Significantly different from FBS samples at P <0.05.

Protein content

FBS samples had higher protein concentrations (33.5±1.8 mg/mL) than HPL samples (22.5±1.5 mg/mL) (P <0.05).

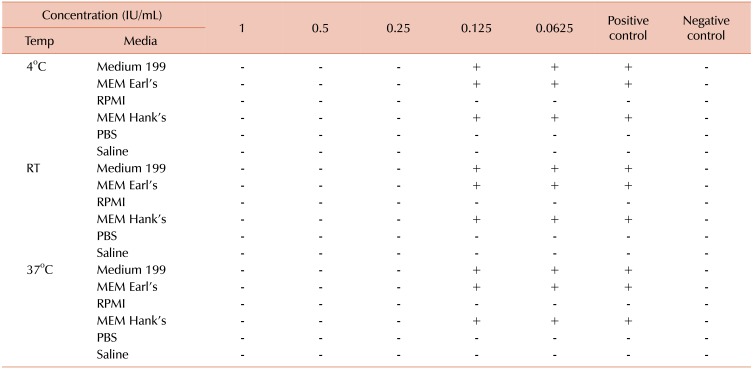

Optimal concentration of heparin

Table 1 shows that gel formation was observed in MEM Earl's, MEM Hank's, and Medium 199 media at heparin concentrations lower than 0.25 IU/mL. No gel formation was observed in RPMI-1640 medium, PBS, and saline at all dilutions. Positive control tubes except for RPMI-1640, PBS, and normal saline showed coagulation at all incubation conditions, while negative control tubes showed clear solution with no coagulation.

Table 1. Different concentrations of heparin in cell culture media at different incubation conditions.

Abbreviations: (+), coagulation; (−), no coagulation; RT, room temperature; temp, incubation temperature.

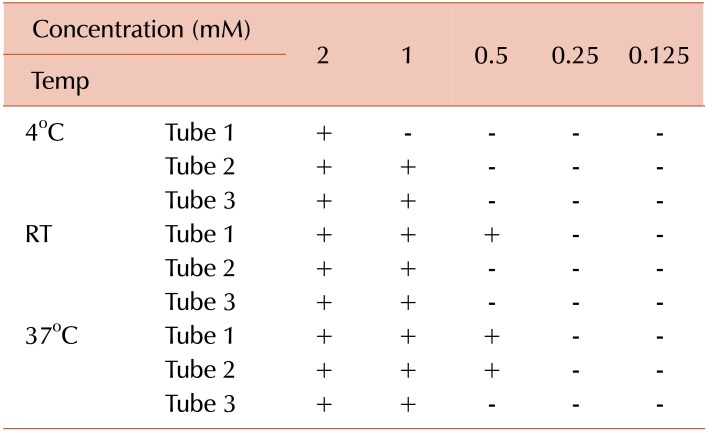

Calcium concentration and coagulation

As seen in Table 2, clotting was observed at all calcium concentrations except 0.25 and 0.125 mM.

Table 2. Different concentrations of calcium in deionized water containing 10% HPL at different incubation conditions.

Abbreviations: (+), coagulation; (−), no coagulation; mM, millimolar; RT, room temperature; temp, incubation temperature.

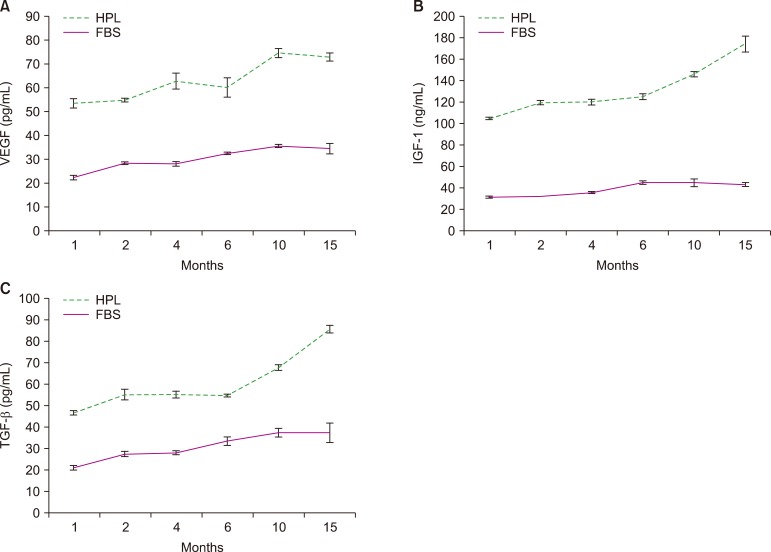

Growth factor stability

Fig. 3 reveals the strong stability of IGF-1, TGF-β, and VEGF in HPL samples stored at −20℃ with an increase in growth factor concentrations in a time-dependent manner. The concentrations of growth factors in HPL were higher than those in FBS at all time points.

Fig. 3. Growth factor stability in HPL and FBS samples stored over 15 months. VEGF (A), IGF-1 (B), TGF-β (C). Values are expressed as means±SD (N=3).

Cell viability assays

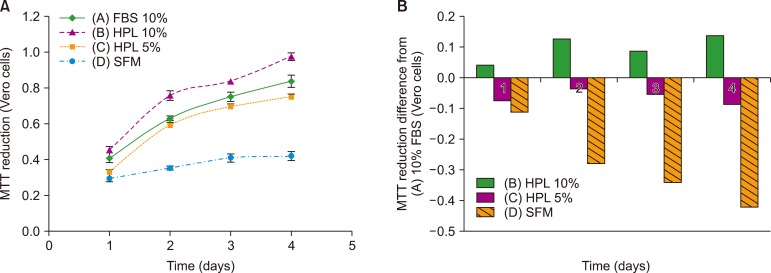

MTT assay

Vero cells: Fig. 4 shows the results of the MTT assay. The cells from group B with 10% HPL showed the highest reduction of MTT dye and differed from the cells from group A (FBS-containing medium). Group A cells showed slightly higher MTT reduction than group C cells (with 5% HPL), as evident from the small difference between these groups. The cells from SFM (group D) group showed the lowest MTT reduction effect and significantly differed from the cells from group A (P <0.05).

Fig. 4. (A) MTT reduction curve for Vero cells cultured in the presence of 10% FBS, 10% HPL, and 5% HPL and in SFM. Data are expressed as means of three independent experiments (P <0.05). (B) MTT reduction difference between cells cultivated in 10% and 5% HPL and SFM and those cultured in 10% FBS (P <0.05).

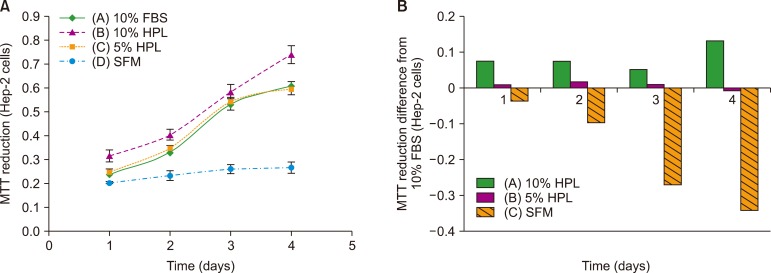

Hep-2 cells: Hep-2 cells cultured in media containing 10% HPL (group B) showed the highest reduction of MTT dye, indicative of high cell viability. The cells cultured in the medium supplemented with 10% FBS (group A) and 5% HPL (group C) showed approximately same viability, while the viability was the lowest for the cells from SFM group (P<0.05) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. (A) MTT reduction curve for Hep-2 cells cultured in the presence of 10% FBS, 10% HPL, and 5% HPL and in SFM (P <0.05). Data are expressed as means±SD of three independent experiments. (B) MTT reduction difference between cells cultivated in 10% and 5% HPL and SFM and those cultured in 10% FBS (P <0.05).

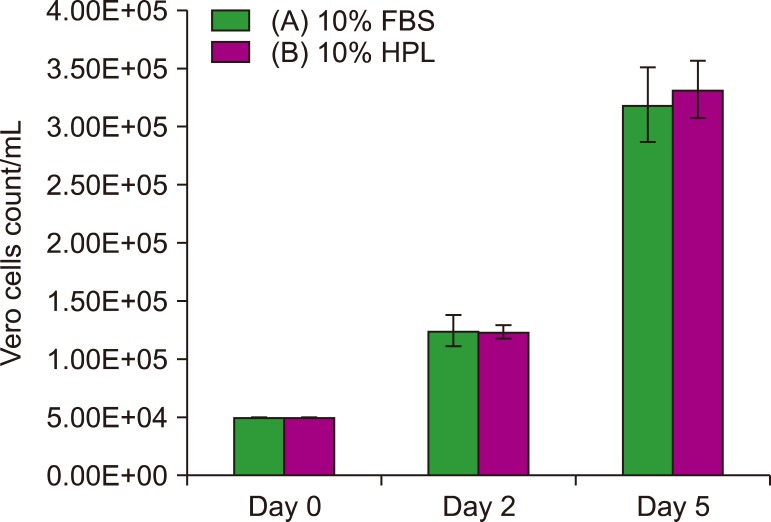

Cell count assay

Vero cells: The results of cell count assay (Fig. 6) show that the two groups A and B had approximately same count at day 2; on day 5, however, the cell count was slightly higher for group B (10% HPL) than that for group A (10% FBS) (P >0.05).

Fig. 6. Count of Vero cells cultured in 10% FBS and 10% HPL. Data are expressed as means±SD of three independent experiments (P >0.05).

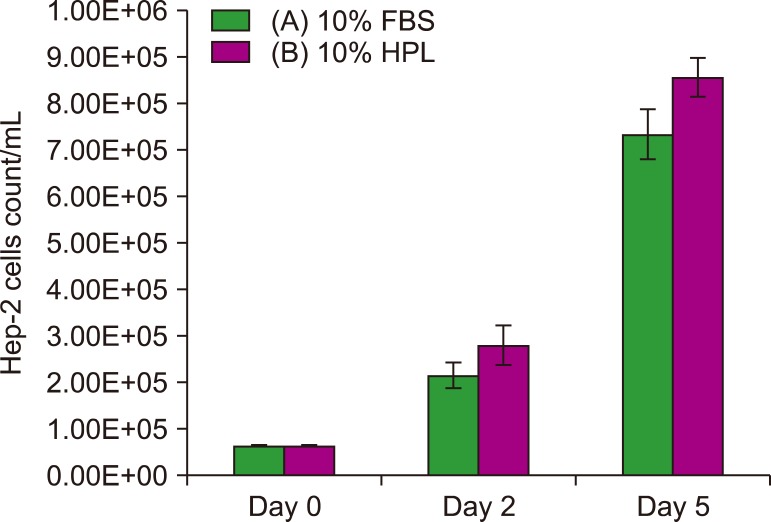

Hep-2 cells: Hep-2 cells cultivated in the medium supplemented with 10% HPL (group B) showed slightly higher count on day 2 and 5 than those cultured in the medium containing 10% FBS (group A; P >0.05) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Count of Hep-2 cells cultivated in 10% FBS and 10% HPL. Data are expressed as means±SD of three independent experiments (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Platelets play a pivotal role in wound healing, cell growth, and tissue regeneration, indicating that HPL may serve as an efficient alternative to FBS. At the site of tissue injury, the attracted platelets not only cause blood clot but also release their granule contents. α-Granules are rich in growth factors such as TGF-β, VEGF, IGF-1, PDGF, and EGF, all of which are involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis [14].

Studies have performed mechanical activation of platelets by repeated freeze/thaw cycles [15] as well as through chemical activation [16]. In the present study, HPL was prepared from freshly pooled human platelets that were subjected to mechanical activation, owing to its simplicity and cost effectiveness. Moreover, this method avoids the need for extra purification steps to remove chemical impurities [17]. We chose (O−) blood group to avoid any possible side-effects related to antigens and blood group determinants [18].

To determine the efficiency of the activation process, platelet count was performed before the activation process and at the end of the preparation process. The obtained data showed a very strong decrease in platelet count, indicative of the high efficiency of the activation process. Growth factor concentrations in HPL have been measured in different studies by comparing different lots of either HPL [19] or HPL and FBS in cell culture supernatants [20]. In the present study, we measured the concentrations of several growth factors in HPL and FBS and found that the concentrations of IGF-1, VEGF, TGF-β, FGF, EGF, and PDGF were significantly higher in HPL than in FBS (P <0.05). Thus, HPL is superior to FBS in terms of growth factor contents and exerts better effects on cell growth. The results of previous studies are not comparable to those of the present study. However, our results support their findings that HPL is a valuable product containing high concentrations of various growth factors and may serve as a growth supplement in cell culture media.

The protein content of HPL was lower than that of FBS, owing to the removal of serum albumin and immunoglobulins during the preparation process. This result was in line with that previously reported in a study comparing the protein content of HPL and human serum [21].

In contrast to FBS, the HPL prepared from platelets contains thrombocyte-derived factors, fibrinogen, and clotting factors, which may lead to gel formation in culture media [22]. To prevent gel formation, the addition of heparin to the medium-containing HPL is critical. However, heparin must be added at very low concentrations, as high concentrations of heparin are cytotoxic and impair cell proliferation [23].

To determine the ideal concentration of heparin for Vero cells cultured in the medium supplemented with HPL, different concentrations of heparin were prepared and added to culture media; the cells were then incubated at different conditions. This test was carried out based on a previous study that revealed the non-toxicity of heparin at 0.61 IU/mL concentration [24]. Therefore determining the lowest effective concentration of heparin below the toxic level would be valuable. We found 0.25 IU/mL heparin was the lowest concentration that prevented gel formation in MEM Earl's, MEM Hank's, and Medium 199 media. On the other hand, heparin was not required in RPMI-1640 medium, PBS, and normal saline.

MEM Earl's, MEM Hank's, and Medium 199 media contain higher calcium (1.8 mM) levels than RPMI-1640 (0.4 mM). Normal saline and PBS has no calcium [25]. According to a previous study, the presence of calcium is essential for coagulation [26]. We found that 0.25 mM or lower calcium concentration in culture media couldn't induce clotting or gel formation in the presence of HPL.

Stability of HPL is important for its application as an FBS substitute. The duration of the stability of the prepared HPL was determined; samples of HPL and FBS were stored at −20℃ for 15 months and tested for concentrations of IGF-1, VEGF, and TGF-β at different time intervals. The data obtained showed that the concentrations of these growth factors remained stable for 15 months, indicating that the prepared HPL exhibited the proliferative power and cell growth-promoting effect during the storage period. Growth factor concentrations in HPL at 10 and 15 months intervals were higher than those detected in previous months, probably owing to the incomplete activation of all platelets by two freeze/thaw cycles. Thus, inclusion of a third cycle may be desirable.

Growth factor stability has been assessed in other studies; however, their results are not comparable to those established herein, as those studies have been conducted for EGF and after only 5 months of storage [21]. Nevertheless, their conclusion is in line with our result that HPL retained its growth factor content after long-term storage at −20℃ or below.

Studies have compared the biological activity of HPL with that of FBS in cell cultures using different models of cell lines such as corneal endothelium cells, MSCs, and human articular cartilage cells. HPL can serve as an efficient alternative to FBS and exerts proliferative and growth-promoting effects [18,27,28]. In skeletal muscle cells, however, the effects of FBS on growth and proliferation were better than those of HPL demonstrating that cell lines response differently to HPL owing to differences in their growth requirements [29]. Thus, formulation of a defined medium for all cell lines is rather challenging.

For the evaluation of the biological activity and growth-promoting effects of HPL on Vero cells, we performed MTT reduction and cell count assays. The results of MTT assay showed no significant difference between 10% FBS and 5% HPL but revealed maximum viability for the cells cultured in the presence of 10% HPL. Cells from SFM showed no notable proliferation. Further, cell count assay revealed no notable difference between cells grown in media containing 10% HPL and 10% FBS.

The results of MTT assay for Hep-2 cells showed that the effect of 5% HPL on cell growth and proliferation was the same as that of 10% FBS, but 10% HPL induced slightly higher proliferation. The cells cultured in SFM had low viability and significantly differed from those cultured in the presence of 10% FBS.

Therefore, HPL is an efficient alternative to FBS for the cultivation of Vero and Hep-2 cells and may be used at 5% than 10% concentration. HPL not only produces similar effects as FBS but is also more economical. The effect of SFM on cultured cells proved that the medium without additives may not support the growth and proliferation of cells but only maintain cell viability.

HPL is a valuable supplement that can be prepared using a simple procedure and may efficiently replace FBS in culture media for Vero and Hep-2 cell lines. While two freeze/thaw cycles are appropriate, a third cycle is recommended. HPL contains higher concentrations of several growth factors such as IGF-1, VEGF, TGF-β, FGF, EGF, and PDGF than FBS and may be stored for up to 15 months at −20℃ to retain its activity. The ideal concentration of heparin to prevent gel formation in MEM Earl's, MEM Hank's, and Medium 199 media supplemented with HPL is 0.25 IU/mL, while heparin supplementation is not required with RPMI, PBS, normal saline, and other cell culture media containing calcium concentrations lower than 0.25 mM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Viral Control Unit, National Organization for Research and Control of Biological, Egypt (VCU, NORCB) who provided expertise that greatly assisted in our research. The authors are thankful to the National Blood Transfusion Center of Egypt (NBTC) for providing platelet units used in this study.

All authors contributed to the proposal, design, and implementation of the study as well as to the result analysis and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Butler M. Animal cell culture and technology. 2nd ed. Oxfordshire, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jochems CE, van der Valk JB, Stafleu FR, Baumans V. The use of fetal bovine serum: ethical or scientific problem? Altern Lab Anim. 2002;30:219–227. doi: 10.1177/026119290203000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montagnon BJ. Polio and rabies vaccines produced in continuous cell lines: a reality for Vero cell line. Dev Biol Stand. 1989;70:27–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett PN, Mundt W, Kistner O, Howard MK. Vero cell platform in vaccine production: moving towards cell culture-based viral vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:607–618. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenny MT, Schell K. Microassay of measles and mumps virus and antibody in VERO cells. J Biol Stand. 1975;3:291–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-1157(75)90033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokomizo AY, Antoniazzi MM, Galdino PL, Azambuja N, Jr, Jorge SA, Pereira CA. Rabies virus production in high vero cell density cultures on macroporous microcarriers. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;85:506–515. doi: 10.1002/bit.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weldon WC, Oberste MS, Pallansch MA. Standardized methods for detection of poliovirus antibodies. In: Martín J, editor. Poliovirus: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2016. pp. 145–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchner C, Bryant C, Eslami A, Lakos G. Anti-nuclear antibody screening using HEp-2 cells. J Vis Exp. 2014:e51211. doi: 10.3791/51211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemeda H, Giebel B, Wagner W. Evaluation of human platelet lysate versus fetal bovine serum for culture of mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnouf T, Strunk D, Koh MB, Schallmoser K. Human platelet lysate: Replacing fetal bovine serum as a gold standard for human cell propagation? Biomaterials. 2016;76:371–387. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nurden AT, Nurden P, Sanchez M, Andia I, Anitua E. Platelets and wound healing. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3532–3548. doi: 10.2741/2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sittampalam GS, Brimacombe K, Arkin M, et al., editors. Assay Guidance Manual. Bethesda, MD: Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis KS, Siegel AC. Cell viability analysis using trypan blue: manual and automated methods. In: Stoddart MJ, editor. Mammalian cell viability: methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2011. pp. 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurden AT. Platelets, inflammation and tissue regeneration. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105 Suppl 1:S13–S33. doi: 10.1160/THS10-11-0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen AB, Butts EB, Copland IB, Stevens HY, Guldberg RE. Human platelet lysate supplementation of mesenchymal stromal cell delivery: issues of xenogenicity and species variability. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;11:2876–2884. doi: 10.1002/term.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roussy Y, Bertrand Duchesne MP, Gagnon G. Activation of human platelet-rich plasmas: effect on growth factors release, cell division and in vivo bone formation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:639–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baik SY, Lim YA, Kang SJ, Ahn SH, Lee WG, Kim CH. Effects of platelet lysate preparations on the proliferation of HaCaT cells. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34:43–50. doi: 10.3343/alm.2014.34.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schallmoser K, Strunk D. Generation of a pool of human platelet lysate and efficient use in cell culture. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;946:349–362. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-128-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce J, Benedetti E, Preslar A, et al. Comparative analyses of industrial-scale human platelet lysate preparations. Transfusion. 2017;57:2858–2869. doi: 10.1111/trf.14324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren J, Ward D, Chen S, et al. Comparison of human bone marrow stromal cells cultured in human platelet growth factors and fetal bovine serum. J Transl Med. 2018;16:65. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rauch C, Feifel E, Amann EM, et al. Alternatives to the use of fetal bovine serum: human platelet lysates as a serum substitute in cell culture media. ALTEX. 2011;28:305–316. doi: 10.14573/altex.2011.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laner-Plamberger S, Lener T, Schmid D, et al. Mechanical fibrinogen-depletion supports heparin-free mesenchymal stem cell propagation in human platelet lysate. J Transl Med. 2015;13:354. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0717-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurbuz HA, Durukan AB, Sevim H, Ergin E, Gurpinar A, Yorgancioglu C. Heparin toxicity in cell culture: a critical link in translation of basic science to clinical practice. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:742–745. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e3283629bbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemeda H, Kalz J, Walenda G, Lohmann M, Wagner W. Heparin concentration is critical for cell culture with human platelet lysate. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:1174–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrad DR. Calcium in cell culture. Darmstadt, Germany: Merck; 2019. [Accessed September 23, 2019]. at https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/life-science/cell-culture/learning-center/media-expert/calcium.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mikaelsson ME. The role of calcium in coagulation and anticoagulation. In: Smit Sibinga C, Das PC, Mannucci PM, editors. Coagulation and blood transfusion. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1991. pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang TJ, Chen MS, Chou ML, Lin HC, Seghatchian J, Burnouf T. Comparison of three human platelet lysates used as supplements for in vitro expansion of corneal endothelium cells. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56:769–773. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen VT, Cancedda R, Descalzi F. Platelet lysate activates quiescent cell proliferation and reprogramming in human articular cartilage: Involvement of hypoxia inducible factor 1. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e1691–e1703. doi: 10.1002/term.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krämer DK, Bouzakri K, Holmqvist O, Al-Khalili L, Krook A. Effect of serum replacement with plysate on cell growth and metabolismin primary cultures of human skeletal muscle. Cytotechnology. 2005;48:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s10616-005-4074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]