Abstract

In this study, we calculated the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values and codon usage bias (CUB) values to implement a comparative analysis of codon usage pattern of open reading frames (ORFs) which belong to the two main genotypes of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). By analysis of synonymous codon usage values in each ORF of PRRSV, the optimal codons for most amino acids were all C or G-ended codons except GAU for Asp, CAU for His, UUU for Phe and CCU for Pro. The synonymous codon usage patterns in different ORFs of PRRSV were different and genetically conserved. Among them, ORF1a, ORF4, ORF5 and ORF7 could cluster these strains into the two main serotypes (EU and US). Due to mutational pressure, compositional constraint played an important role in shaping the synonymous codon usage pattern in different ORFs, and the synonymous codon usage diversity in ORFs was correlated with gene function. The degree of CUB for some particular amino acids under strong selection pressure probably served as a potential genetic marker for each ORF in PRRSV. However, gene length and translational selection in nature had no effect on the synonymous codon usage pattern in PRRSV. These conclusions could not only offer an insight into the synonymous codon usage pattern and differentiation of gene function, but also assist in understanding the discrepancy of evolution among ORFs in PRRSV.

Keywords: Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, Relative synonymous codon usage, Codon usage bias, Mutational pressure, Genetic marker

1. Introduction

It is well known that the genetic code chooses 64 codons to represent 20 standard amino acids and stop signals. These alternative codons for the same amino acid are termed as synonymous codons. Although synonymous mutations tend to occur in the third base position, the cases can be interchanged without altering the primary sequence of the protein product. Some reports indicate that synonymous codons are not chosen equally and randomly both within and between genomes (Dittmar et al., 2006, Grantham et al., 1980, Lloyd and Sharp, 1992, Martin et al., 1989, Xie et al., 1998). In general, translation selection in nature and compositional constraints under the mutational pressure are thought to be the two major factors accounting for codon usage variation among genomes in various organisms (Gu et al., 2004, Karlin and Mrázek, 1996, Lesnik et al., 2000, Sharp et al., 1986, Zhong et al., 2007, Zhou et al., 2005, Zhou et al., 2006). In some RNA viruses, compared with translation selection in nature, mutation pressure plays an important role in synonymous codon usage pattern (Gu et al., 2004, Levin and Whittome, 2000, Jenkins and Holmes, 2003).

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is an enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus which is classified into the order Nidovirales of family Arteriviridae (Benfield et al., 1992, Cavanagh, 1997). Based on serological characteristics, there are the two main serotypes of PRRSV, namely the Northern American isolate (US) and the European isolate (EU) (Bautista et al., 1993, Collins et al., 1992, Meng et al., 1995, Wensvoort et al., 1991). In addition to differences between both serotypes of the viruses, there is obvious genetic variation within PRRSVs, as confirmed by measure of the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the viruses. The PRRSV genome contains ORF1a, encoding papain-like cysteine protease, ORF1b, encoding RNA dependent RNA polymerase, ORF2-6, encoding envelop proteins, and ORF7, encoding the nucleocapsid protein (Conzelmann et al., 1993, Meulenberg et al., 1993). The PRRSV can infect swine population and lead to a series of clinical signs, including high mortality, reproductive failure, post-weaning pneumonia and growth reduction (Keffaber, 1989, Loula, 1991). It is reported that PRRSV could give rise to prolonged viremia and enable its replication in macrophages, and lead to persistent infections (Plagemann and Moennig, 1992). However, little information about codon usage pattern of PRRSV genome including the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) and codon usage bias (CUB) in the process of their evolution are available. In this study, the key genetic determinants of codon usage index in PRRSV were examined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sequence data

The 13 complete RNA sequences of PRRSV were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/) and detailed information about the viruses were listed in Table 1 . The nucleotide content of ORFs of each PRRSV strain were analyzed by biosoftware DNAStar 7.0 for windows.

Table 1.

PRRSV isolates and genome sequences included in this study.

| No. | Strain | Serotype | Isolation | Length (bp) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16244B (US field strain) | US | USA | 15,428 | NC_001961 |

| 2 | SY0608 (US field strain) | US | China | 15,335 | EU144079 |

| 3 | ATCC VR-2332 (US prototype) | US | USA | 15,411 | U87392 |

| 4 | EuroPRRSV (EU field strain) | EU | USA | 15,047 | AY366525 |

| 5 | Lelystad (EU field strain) | EU | Netherlands | 15,111 | M96262 |

| 6 | Ingelvac MLV (US vaccine strain) | US | USA | 15,412 | EF484033 |

| 7 | HB-2(sh)/2002 (US field strain) | US | China | 15,398 | AY262352 |

| 8 | Prime Pac (US vaccine starin) | US | USA | 15,521 | DQ779791 |

| 9 | KNU-07 (EU field strain) | EU | South Korea | 15,038 | FJ349261 |

| 10 | 01CB1 (EU field strain) | EU | Thailand | 14,943 | DQ864705 |

| 11 | BJEU06-1 (EU field strain) | EU | China | 15,059 | GU047344 |

| 12 | HKEU16 (EU field strain) | EU | China: Hong Kong | 15,074 | EU076704 |

| 13 | NMEU 09-1 (EU filed strain) | EU | China | 15,068 | GU047345 |

2.2. The calculation of the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU)

To investigate the characteristics of synonymous codon usage without the confounding influence of amino acid composition among different sequences, the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values among different codons in each ORF was calculated. The RSCU value of the ith codon for the jth amino acid was calculated according to the published equation (Sharp and Li, 1986). RSCU:

where g ij is the observed number of the ith codon for jth amino acid which has n i type of synonymous codons. The codons with RSCU values more than 1.0 have positive CUB, while the values <1.0 have relative negative CUB. When RSCU value is equal to 1.0, it means that this codon is chosen equally and randomly.

2.3. Codon usage bias (CUB) calculations

To calculate CUB, it is supposed that statistically equal and random usage of all available synonymous codons was the “neutral point” (RSCU0 = 1.00) for the development of serotype-specific codon usage (Zhou et al., 2010). CUB:

More simply, CUB is the average value of difference between RSCUij and RSCU0 at each position of the target region. n represents all codons appearing in this position. When all RSCU values according to a particular position in the target region are RSCU0, CUB is equal to 0. It means that there are few preferential or non-preferential codons existing at this position. In contrast, when CUB value is much more deviation than RSCU0, codons with CUB are preferentially chosen at a particular position.

2.4. Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis, which was a commonly used multivariate statistical method (Jolliffe, 2002, Mardia et al., 1979), was carried out to analyze the major trend in codon usage pattern among different strains. Each strain was represented as a 59 dimensional vector, and each dimension corresponded to the RSCU value of each sense codon, which only included several synonymous codons for a particular amino acid, excluding the codon of AUG, UGG and three stop codons.

We set up a two-dimensional coordinate system, which was made up of the first principal component and the second principal component . This two-dimensional coordinate would report the genetic relationship among all strains.

2.5. Correlation analysis

Correlation analysis of PRRSV was used to identify the relationship between nucleotide composition and synonymous codon usage pattern (Ewens and Grant, 2001). This analysis was implemented based on the Spearman's rank correlation analysis way.

All statistical processes were carried out by with statistical software SPSS11.5 for windows.

3. Results

3.1. Synonymous codon usage in PRRSV

The nucleotide contents in each ORF of 13 PRRSV isolates were analyzed and the comparison among the values of A3%, U3%, C3% and G3% indicated that the content of A3 was always lowest and the rest fluctuated similarly. The (C3 + G3)% in ORFs of PRRSV fluctuates from 38.13% to 59.68% (Table 2 ). The overall RSCU values of 59 sense codons in PRRSV were listed in Table 3 , respectively. Most optimal codons among strains represent C-ended or G-ended codons, however, there was an interesting findings that four codons of GAU, CAU, UUU, CCU and their corresponding amino acids of Asp, His, Phe, Pro were chosen preferentially. Most of A-ended codons, excluding CCA and UCA with little slight preferential usage for Pro and Ser were used weakly (Table 3). These results suggested that compositional limitation often played an integral role in the codon usage pattern of PRRSV.

Table 2.

Identified ORFs (length > 250 bps) in the PRRSV (13 isolates) genome.

| ORF | No. | A% | A3% | U% | U3% | C% | C3% | G% | G3% | (C + G)% | (C3 + G3)% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1 | 20.45 | 16.35 | 24.96 | 28.13 | 27.24 | 32.16 | 27.36 | 23.34 | 54.59 | 55.51 |

| 2 | 20.42 | 16.00 | 25.04 | 29.35 | 26.98 | 31.25 | 27.57 | 23.37 | 54.55 | 54.63 | |

| 3 | 20.46 | 16.18 | 25.04 | 28.36 | 27.24 | 32.02 | 27.26 | 23.41 | 54.50 | 55.44 | |

| 4 | 20.11 | 16.64 | 26.83 | 32.02 | 27.55 | 31.10 | 25.50 | 20.22 | 53.05 | 51.33 | |

| 5 | 20.84 | 17.17 | 25.09 | 28.19 | 27.02 | 31.68 | 27.05 | 22.95 | 54.07 | 54.63 | |

| 6 | 20.47 | 16.13 | 25.08 | 28.41 | 27.21 | 32.02 | 27.25 | 23.41 | 54.45 | 55.44 | |

| 7 | 20.76 | 17.04 | 25.70 | 29.59 | 26.55 | 30.51 | 26.99 | 22.84 | 53.53 | 53.35 | |

| 8 | 20.83 | 17.22 | 25.06 | 28.3 | 27.05 | 31.76 | 27.06 | 23.07 | 54.11 | 54.84 | |

| 9 | 20.04 | 16.60 | 26.81 | 32.25 | 27.67 | 31.07 | 25.48 | 20.07 | 53.15 | 51.13 | |

| 10 | 19.97 | 16.63 | 26.66 | 31.57 | 27.78 | 31.48 | 25.59 | 20.31 | 53.37 | 51.79 | |

| 11 | 19.76 | 16.71 | 26.91 | 31.82 | 27.72 | 31.48 | 25.61 | 19.97 | 27.72 | 51.45 | |

| 12 | 19.90 | 16.29 | 26.91 | 32.31 | 27.56 | 31.45 | 25.63 | 19.93 | 53.19 | 51.39 | |

| 13 | 19.69 | 16.23 | 26.65 | 31.55 | 27.71 | 31.34 | 25.94 | 20.86 | 53.65 | 52.20 | |

| 1b | 1 | 23.42 | 17.46 | 23.58 | 26.16 | 27.67 | 34.72 | 25.34 | 21.64 | 53.00 | 56.36 |

| 2 | 23.52 | 17.23 | 23.77 | 28.10 | 27.21 | 32.83 | 25.50 | 21.82 | 52.71 | 54.66 | |

| 3 | 23.46 | 17.62 | 23.82 | 26.75 | 27.37 | 34.11 | 25.35 | 21.51 | 52.72 | 55.62 | |

| 4 | 23.62 | 19.54 | 24.26 | 28.39 | 26.91 | 30.45 | 25.20 | 21.60 | 52.11 | 52.05 | |

| 5 | 23.77 | 18.29 | 24.09 | 27.61 | 27.12 | 33.47 | 25.02 | 20.62 | 52.14 | 54.09 | |

| 6 | 23.62 | 17.90 | 23.82 | 26.96 | 27.37 | 33.82 | 25.19 | 21.30 | 52.56 | 55.13 | |

| 7 | 23.38 | 18.05 | 24.41 | 28.7 | 26.87 | 32.22 | 25.34 | 21.01 | 52.21 | 53.24 | |

| 8 | 23.92 | 18.21 | 24.08 | 27.64 | 27.19 | 33.54 | 24.82 | 20.59 | 52.01 | 54.13 | |

| 9 | 23.65 | 18.61 | 23.78 | 26.68 | 27.48 | 32.55 | 25.09 | 22.15 | 52.57 | 54.70 | |

| 10 | 23.86 | 19.88 | 23.88 | 27.50 | 27.35 | 31.31 | 24.91 | 21.29 | 52.25 | 52.60 | |

| 11 | 23.68 | 19.30 | 24.02 | 27.48 | 27.21 | 31.43 | 25.09 | 21.77 | 52.30 | 53.20 | |

| 12 | 23.77 | 19.46 | 23.95 | 27.22 | 27.25 | 31.59 | 25.02 | 21.72 | 52.28 | 53.31 | |

| 13 | 23.68 | 19.60 | 23.63 | 26.09 | 27.39 | 32.15 | 27.39 | 22.14 | 52.69 | 54.30 | |

| 2 | 1 | 21.27 | 22.97 | 32.43 | 35.31 | 22.96 | 20.00 | 23.35 | 21.70 | 46.30 | 41.70 |

| 2 | 20.88 | 21.27 | 32.22 | 34.89 | 23.22 | 20.85 | 23.22 | 22.97 | 46.43 | 43.82 | |

| 3 | 20.88 | 22.12 | 32.30 | 35.31 | 22.96 | 19.57 | 23.87 | 22.97 | 46.82 | 42.55 | |

| 4 | 19.60 | 18.88 | 29.47 | 28.32 | 26.93 | 29.61 | 24.00 | 23.17 | 50.93 | 52.78 | |

| 5 | 19.58 | 19.65 | 32.17 | 35.04 | 23.22 | 20.51 | 25.03 | 24.78 | 48.25 | 45.29 | |

| 6 | 20.88 | 22.12 | 32.68 | 36.17 | 22.96 | 19.57 | 23.48 | 22.12 | 46.43 | 41.70 | |

| 7 | 20.75 | 22.12 | 32.17 | 33.61 | 23.61 | 22.55 | 23.48 | 21.70 | 47.08 | 44.25 | |

| 8 | 19.58 | 19.65 | 32.17 | 35.04 | 23.22 | 20.51 | 25.03 | 24.78 | 48.25 | 45.29 | |

| 9 | 20.53 | 20.17 | 30.00 | 28.32 | 26.40 | 29.61 | 23.07 | 21.88 | 49.47 | 51.50 | |

| 10 | 19.47 | 18.88 | 29.60 | 27.46 | 26.93 | 30.47 | 24.00 | 23.17 | 50.93 | 53.64 | |

| 11 | 19.20 | 18.10 | 29.73 | 28.44 | 27.07 | 30.17 | 24.00 | 23.27 | 51.07 | 53.44 | |

| 12 | 20.27 | 21.45 | 30.00 | 29.18 | 26.80 | 29.18 | 22.93 | 20.17 | 49.73 | 49.00 | |

| 13 | 20.00 | 21.03 | 30.27 | 28.32 | 26.13 | 29.61 | 23.60 | 21.03 | 49.73 | 53.00 | |

| 3 | 1 | 20.00 | 16.73 | 29.28 | 28.97 | 26.01 | 31.83 | 24.71 | 22.44 | 50.72 | 54.28 |

| 2 | 20.52 | 16.04 | 29.28 | 30.86 | 26.14 | 33.33 | 24.05 | 19.75 | 50.20 | 53.08 | |

| 3 | 20.52 | 17.55 | 29.15 | 28.97 | 26.14 | 32.24 | 24.18 | 21.22 | 50.33 | 53.46 | |

| 4 | 22.06 | 19.92 | 28.32 | 27.09 | 26.82 | 31.87 | 22.81 | 21.11 | 49.62 | 52.98 | |

| 5 | 19.08 | 15.51 | 28.89 | 28.97 | 26.67 | 33.06 | 25.36 | 22.44 | 52.03 | 55.51 | |

| 6 | 20.78 | 17.14 | 23.92 | 29.38 | 29.28 | 31.83 | 26.01 | 21.63 | 49.93 | 53.46 | |

| 7 | 18.90 | 14.40 | 29.00 | 30.45 | 26.90 | 33.33 | 25.20 | 21.81 | 52.10 | 55.14 | |

| 8 | 19.08 | 15.51 | 28.89 | 28.97 | 26.67 | 33.06 | 25.36 | 22.44 | 52.03 | 55.51 | |

| 9 | 23.18 | 20.15 | 27.57 | 26.48 | 26.94 | 33.59 | 22.31 | 19.76 | 49.25 | 53.35 | |

| 10 | 21.18 | 17.39 | 27.57 | 26.48 | 27.44 | 32.01 | 23.81 | 24.11 | 51.25 | 56.12 | |

| 11 | 21.32 | 18.36 | 29.20 | 28.57 | 27.13 | 31.02 | 22.35 | 22.04 | 49.48 | 53.06 | |

| 12 | 22.09 | 20.32 | 28.29 | 27.23 | 27.52 | 32.11 | 22.09 | 20.32 | 49.61 | 52.43 | |

| 13 | 21.19 | 18.36 | 28.17 | 26.12 | 27.52 | 33.87 | 23.13 | 21.63 | 50.65 | 55.51 | |

| 4 | 1 | 19.93 | 13.37 | 31.66 | 35.46 | 24.77 | 29.65 | 23.65 | 21.51 | 48.42 | 51.16 |

| 2 | 20.30 | 13.95 | 31.66 | 30.23 | 24.77 | 36.04 | 23.28 | 19.76 | 48.04 | 55.81 | |

| 3 | 20.30 | 13.37 | 23.28 | 35.46 | 31.66 | 29.65 | 24.77 | 21.51 | 48.04 | 51.16 | |

| 4 | 22.28 | 14.77 | 28.80 | 31.81 | 26.63 | 30.68 | 22.28 | 22.72 | 48.91 | 53.40 | |

| 5 | 19.18 | 12.20 | 31.10 | 33.72 | 25.70 | 31.97 | 24.02 | 22.09 | 49.72 | 54.06 | |

| 6 | 20.11 | 13.37 | 23.65 | 34.88 | 31.28 | 30.23 | 24.95 | 21.51 | 48.60 | 51.74 | |

| 7 | 20.48 | 15.11 | 30.35 | 30.81 | 26.63 | 34.88 | 22.53 | 19.18 | 49.16 | 54.06 | |

| 8 | 19.18 | 12.20 | 31.10 | 33.72 | 25.70 | 31.97 | 24.02 | 22.09 | 49.72 | 54.06 | |

| 9 | 22.64 | 15.34 | 27.17 | 26.7 | 28.26 | 34.65 | 21.92 | 23.29 | 50.18 | 57.95 | |

| 10 | 21.38 | 14.77 | 28.44 | 30.68 | 26.99 | 31.81 | 23.19 | 22.72 | 50.18 | 54.54 | |

| 11 | 21.21 | 14.28 | 29.73 | 30.95 | 26.70 | 32.14 | 22.35 | 22.61 | 49.05 | 54.76 | |

| 12 | 20.83 | 12.94 | 29.55 | 32.94 | 26.52 | 29.41 | 23.11 | 24.70 | 49.62 | 54.11 | |

| 13 | 21.02 | 13.60 | 29.55 | 31.36 | 26.33 | 30.76 | 23.11 | 24.26 | 49.43 | 55.02 | |

| 5 | 1 | 20.23 | 13.54 | 29.68 | 30.72 | 24.05 | 34.37 | 26.04 | 21.35 | 50.08 | 55.72 |

| 2 | 20.07 | 11.97 | 29.35 | 30.20 | 24.71 | 33.33 | 25.87 | 24.47 | 50.58 | 57.81 | |

| 3 | 20.40 | 13.54 | 25.87 | 30.72 | 29.35 | 34.37 | 24.38 | 21.35 | 50.25 | 55.72 | |

| 4 | 20.46 | 15.10 | 29.54 | 30.2 | 24.26 | 35.93 | 25.74 | 18.75 | 50.00 | 54.68 | |

| 5 | 20.07 | 13.54 | 30.02 | 30.2 | 23.22 | 32.29 | 26.70 | 23.95 | 49.92 | 56.25 | |

| 6 | 20.40 | 13.54 | 29.35 | 30.72 | 24.38 | 34.37 | 25.87 | 21.35 | 50.25 | 55.72 | |

| 7 | 19.90 | 12.50 | 30.51 | 32.29 | 23.05 | 31.25 | 26.53 | 23.95 | 49.59 | 55.20 | |

| 8 | 20.07 | 13.54 | 30.02 | 30.20 | 23.22 | 32.29 | 26.70 | 23.95 | 49.92 | 56.25 | |

| 9 | 19.64 | 13.54 | 28.22 | 26.56 | 25.58 | 37.50 | 26.57 | 22.39 | 52.15 | 59.89 | |

| 10 | 20.13 | 17.18 | 27.72 | 25.52 | 25.91 | 39.58 | 26.24 | 17.70 | 52.15 | 57.29 | |

| 11 | 21.62 | 17.70 | 28.22 | 28.12 | 25.25 | 35.93 | 24.92 | 18.00 | 50.17 | 54.16 | |

| 12 | 19.47 | 13.98 | 28.88 | 29.53 | 24.59 | 35.23 | 27.06 | 22.00 | 51.65 | 56.47 | |

| 13 | 21.78 | 16.31 | 29.54 | 31.57 | 22.77 | 31.57 | 25.91 | 20.52 | 48.68 | 52.10 | |

| 6 | 1 | 22.29 | 17.85 | 26.29 | 23.21 | 25.90 | 34.52 | 25.52 | 24.40 | 51.43 | 58.92 |

| 2 | 22.67 | 19.64 | 26.48 | 24.40 | 25.71 | 32.73 | 25.14 | 23.21 | 50.86 | 55.95 | |

| 3 | 22.67 | 19.64 | 26.48 | 24.40 | 25.71 | 32.73 | 25.14 | 23.21 | 50.86 | 55.95 | |

| 4 | 23.37 | 27.38 | 25.48 | 23.21 | 27.01 | 33.92 | 24.14 | 15.47 | 51.15 | 49.40 | |

| 5 | 21.52 | 17.85 | 27.05 | 26.19 | 24.95 | 30.95 | 26.48 | 25.00 | 51.43 | 55.95 | |

| 6 | 22.67 | 19.64 | 26.48 | 24.40 | 25.52 | 33.33 | 25.33 | 22.61 | 50.86 | 55.95 | |

| 7 | 22.29 | 19.04 | 26.48 | 23.80 | 25.52 | 33.33 | 25.71 | 23.80 | 51.24 | 57.14 | |

| 8 | 21.52 | 17.85 | 27.05 | 26.19 | 24.95 | 30.95 | 26.48 | 25.00 | 51.43 | 55.95 | |

| 9 | 22.03 | 24.40 | 26.05 | 24.40 | 26.25 | 32.14 | 25.67 | 19.04 | 51.92 | 51.19 | |

| 10 | 23.37 | 26.19 | 26.63 | 25.59 | 25.86 | 31.54 | 24.14 | 16.66 | 50.00 | 48.21 | |

| 11 | 24.52 | 14.28 | 25.29 | 30.95 | 26.63 | 32.14 | 23.56 | 22.61 | 50.19 | 54.76 | |

| 12 | 21.84 | 22.75 | 25.86 | 20.95 | 26.63 | 37.12 | 25.67 | 19.16 | 52.30 | 56.28 | |

| 13 | 22.80 | 23.95 | 27.01 | 26.94 | 25.10 | 30.53 | 25.10 | 18.56 | 50.19 | 49.10 | |

| 7 | 1 | 30.11 | 19.00 | 19.09 | 23.96 | 25.27 | 23.96 | 25.54 | 33.05 | 50.81 | 57.02 |

| 2 | 30.11 | 19.83 | 19.35 | 21.48 | 24.73 | 24.79 | 25.81 | 33.88 | 50.54 | 58.67 | |

| 3 | 30.11 | 19.00 | 19.35 | 24.79 | 25.00 | 23.14 | 25.54 | 33.05 | 50.54 | 56.19 | |

| 4 | 27.65 | 20.16 | 19.90 | 25.80 | 26.10 | 22.48 | 26.36 | 31.45 | 52.45 | 54.03 | |

| 5 | 30.38 | 19.00 | 19.09 | 23.14 | 25.81 | 25.61 | 24.73 | 32.23 | 50.54 | 57.85 | |

| 6 | 30.11 | 19.00 | 19.35 | 24.79 | 25.00 | 23.14 | 25.54 | 33.05 | 50.54 | 56.19 | |

| 7 | 29.03 | 19.00 | 18.28 | 19.83 | 25.81 | 26.44 | 26.88 | 34.71 | 52.69 | 59.82 | |

| 8 | 30.38 | 19.00 | 19.09 | 23.14 | 25.81 | 25.61 | 24.73 | 32.23 | 50.54 | 57.85 | |

| 9 | 28.17 | 20.16 | 21.19 | 25.80 | 25.32 | 23.38 | 25.32 | 30.64 | 50.65 | 54.03 | |

| 10 | 27.39 | 19.35 | 19.90 | 25.00 | 26.61 | 24.19 | 20.10 | 31.45 | 52.71 | 55.64 | |

| 11 | 27.39 | 21.13 | 19.90 | 26.82 | 26.61 | 23.57 | 26.10 | 28.45 | 52.71 | 52.03 | |

| 12 | 26.36 | 18.69 | 20.16 | 29.26 | 27.13 | 25.20 | 26.36 | 31.70 | 53.49 | 56.91 | |

| 13 | 27.13 | 17.74 | 20.93 | 28.22 | 25.32 | 20.96 | 26.61 | 33.06 | 51.94 | 54.03 | |

Table 3.

Synonymous codon usage in PRRSV ORFs.

| AAa | Codon | RSCUb | AAa | Codon | RSCUb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | GCA | 0.857 | Leu | CUA | 0.510 |

| GCC | 1.309 | CUC | 1.164 | ||

| GCG | 0.650 | CUG | 1.377 | ||

| GCU | 1.184 | CUU | 1.096 | ||

| Arg | AGA | 0.893 | UUA | 0.330 | |

| AGG | 1.092 | UUG | 1.522 | ||

| CGA | 0.742 | Lys | AAA | 0.997 | |

| CGC | 1.411 | AAG | 1.003 | ||

| CGG | 1.012 | Phec | UUC | 0.917 | |

| CGU | 0.851 | UUU | 1.083 | ||

| Asn | AAC | 1.040 | Proc | CCA | 1.047 |

| AAU | 0.960 | CCC | 1.059 | ||

| Aspc | GAC | 0.955 | CCG | 0.802 | |

| GAU | 1.045 | CCU | 1.092 | ||

| Cys | UGC | 1.001 | Ser | AGC | 0.872 |

| UGU | 0.999 | AGU | 0.806 | ||

| Gln | CAA | 0.982 | UCA | 1.075 | |

| CAG | 1.018 | UCC | 1.418 | ||

| Glu | GAA | 0.884 | UCG | 0.683 | |

| GAG | 1.116 | UCU | 1.145 | ||

| Gly | GGA | 0.559 | Thr | ACA | 0.969 |

| GGC | 1.369 | ACC | 1.439 | ||

| GGG | 1.016 | ACG | 0.653 | ||

| GGU | 1.056 | ACU | 0.939 | ||

| Hisc | CAC | 0.847 | Tyr | UAC | 1.174 |

| CAU | 1.153 | UAU | 0.826 | ||

| Ile | AUA | 0.766 | Val | GUA | 0.365 |

| AUC | 1.166 | GUC | 1.110 | ||

| AUU | 1.068 | GUG | 1.406 | ||

| GUU | 1.118 | ||||

The preferentially used codons for each amino acid are described in bold.

AA is the abbreviation of amino acid.

RSCU values are mean values.

The preferentially used codon is U-end codon.

3.2. Genetic relationship based on synonymous codon usage in PRRSV

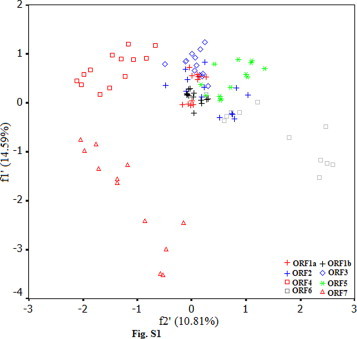

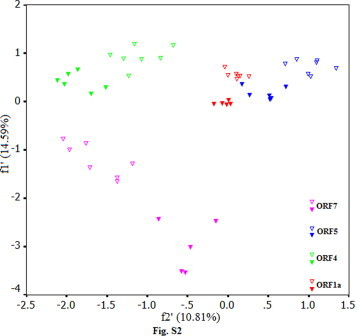

Principal component analysis was carried out for the identified ORFs of all samples. The method detected one major trend in the first axis which can account for 14.59% of the total synonymous codon usage variation, and another major trend in the second axis for 10.81% of the total variation. A plot of the and the of each ORF in PRRSV is shown in Fig. S1. It appeared to be a little complex with some overlapping plots of ORF1a to ORF7. The plots of ORF1a and ORF1b which can produce viral nonstructural proteins aggregated highly, however, the plots of the rest scattered to different extents (Fig. S1). It was clear that the plots of ORF4-7 were far from each other obviously, implying that the functions of differential viral products played a role in codon usage pattern. The ORF1a, ORF4, ORF5 and ORF7 could distinguish US and EU serotypes obviously, and these plots reflected codon usage pattern corresponding to each ORF (Fig. S2). It is probably been suggested during the evolution of PRRSV, the function of viral proteins enabled PRRSV genome to shape the characteristic of the US and the EU serotypes of PRRSV. The ORF1a could reflect the conserved pattern of synonymous codon usage between the two serotypes compared with ORF4, 5 and 7. This phenomenon reflected that synonymous codon usage pattern of ORF1a was relatively conserved due to the function of nonstructural protein of PRRSV, in contrast, due to the functions of structural proteins, the codon usage patterns of ORF4, 5 and 7 for structural proteins were relative variable. However, the scattered plots of ORF3 reflected that the two main serotypes had a common characteristic of synonymous codon usage pattern, namely, the plots failed to distinguish the two virus serotypes obviously. It suggested that the viral product encoded by ORF3 of different serotypes of PRRSV had a slight ability to identify between US and EU serotypes.

3.3. Compositional properties of all ORFs of PRRSV

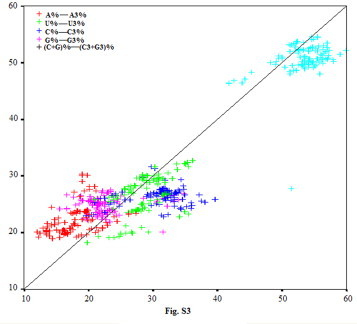

To analyze if the different viruses’ ORFs displayed similar compositional characteristics, all and values for strains were calculated by principle component analysis, and all the obtained positions content of A, U, C, G, and (C + G) (A%, U%, C%, G%, (C + G)%), and the third position content of A, U, C, G and (C3 + G3) (A3%, U3%, C3%, G3%, (C3 + G3)), were measured and listed in Table 2. By analysis of overlay scatter-plot, the content of each nucleotide at the synonymous third position of sense codons did not fluctuate following the total content of corresponding nucleotide, especially A3%, C3%, G3% (Fig. S3). It is implied that the pattern of synonymous codon usage may not be directly and simply correlated to nucleotide content, but to selection pressure (e.g. mutation pressure and gene function). However, it was observed that the relationship between (C3 + G3)% and (C + G)% did not reveal some special features, namely it did not reflect the real variation of C3% or G3%. Thus, the variation of (C3 + G3)% may have a slight correlation with the codon usage pattern of PRRSV.

To analyze codon usage pattern regulated by natural selection or mutation pressure, the A%, U%, C%, G% and (C + G)% were compared with A3%, U3%, C3%, G3% and (C3 + G3)%, respectively. An interesting and complex correlation was observed. In detail, it was apparent that positive correlation existed among the nucleotide contents (i.e., A% and A3%) (p < 0.01), however, there were three different correlation degrees including positive correlation, negative correlation or non-correlation among the nucleotides. Further, A3% has no correlation with C% or G%, suggesting nucleotide constraint can influence codon usage of the nucleotide A at the synonymous codon; the fluctuation of U3% can be affected by A%, C% and G%, respectively, and C3% is not related to G%, they does not indicate some special feature; however, G3% has a strong positive correlation with A% and non-correlation with C%, indicating (C + G)% and (C3 + G3)% may not reflect some true feature of synonymous codon usage as well (Table 4 ). In addition, the and values were compared with nucleotide composition of each sample (Table 5 ). Although the codon usage patterns in different strains appeared to be related to (C3 + G3)% to a slight extent, correlation analysis has been carried out to find significant correlation between nucleotide compositions and synonymous codon usage to a certain extent. In addition, there is no obvious relationship between codon usage indices ( values) and the length of different ORFs, for example there is no significant difference among codon usage indices for ORF1a, ORF1b and ORF2 (p > 0.05), implying that the different length of genes did not account for codon usage variation of ORFs in PRRSV. Taken together, these analyses indicate that nucleotide compositions play a role in the pattern of codon usage. Furthermore, mutational pressure is the main factor responsible for the variation of synonymous codon usage among samples.

Table 4.

Summary of correlation analysis between the A, U, C, G contents and A3, U3, C3, G3 contents in all selected samples.

| A3% | U3% | C3% | G3% | (C3 + G3)% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A% | r = 0.378** | r = −0.612** | r = −0.433** | r = 0.738** | r = 0.249** |

| U% | r = −0.201* | r = 0.635** | r = 0.170NS | r = −0.613** | r = −0.458** |

| C% | r = −0.124NS | r = −0.125NS | r = 0.368** | r = −0.189NS | r = 0.239* |

| G% | r = −0.131NS | r = −0.192NS | r = 0.108NS | r = 0.332** | r = 0.306** |

| (C + G)% | r = −0.006NS | r = −0.367** | r = 0.198* | r = 0.126NS | r = 0.375** |

NS means non-significant (p > 0.05).

Means 0.01 < p < 0.05.

Means p < 0.01.

Table 5.

Summary of correlation analysis between the first two axes in principle and nucleotide contents in samples.

| Base compositions | (15.083%) | (11.171%) |

|---|---|---|

| A3% | r = −0.449** | r = 0.441** |

| U3% | r = 0.529** | r = −0.219** |

| C3% | r = 0.519** | r = 0.256** |

| G3% | r = −0.695** | r = −0.454** |

| (C3 + G3)% | r = −0.128NS | r = −0.194** |

NS means non-significant.

Means p < 0.01.

3.4. Qualitative evaluation of codon usage bias in ORFs of PRRSV

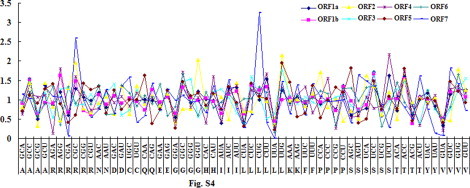

There was a seemingly random variation in CUB between amino acids and ORFs. There were several synonymous codons with strong discrepancy for codon usage in each ORF. In details, as for ORF2, GGU for Gly, UUG for Leu, CCA for Pro are chosen preferentially; in ORF3, GAC for Asp, GGG for Gly, GUU for Val are chosen preferentially; in ORF4, AGG for Arg, CAU for His, CCC for Pro are used preferentially; in ORF5, CAA for Gln, AAA for Lys, CCG for Pro, AGC for Ser are used preferentially; in ORF6, GAA for Glu, CAC for Thr, ACA for Thr are used preferentially; as for ORF7, CGC for Arg, UGC for Cys, CUG for Leu, AAG for Lys, AGU for Ser, ACU for Thr, GUC for Val. In ORF1a–1b, there is no preferential condon (Fig. S4). These results may suggest that with the development of evolution of PRRSV, the discrepancy of synonymous codon usage was formed by accumulation of mutation.

3.5. Relationship between amino acids and codon usage pattern in PRRSV

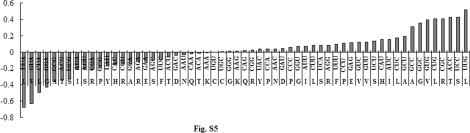

In order to analyze whether the evolution of CUB was controlled by mutation pressure or by translational selection in nature, the CUB data had been calculated based on data listed in Table 3. This table displayed a numerical representation of the translational machinery. The distribution of CUB values is illustrated in Fig. S5. The transition from maximum-negative to maximum-positive values was smooth and there was no obvious or unambiguous border between the so-called dominant and prohibited codons, namely, all possible codons were used. The result indicated that translational selection in nature has no effect on the pattern of synonymous codon usage and the evolutionary pattern of PRRSV.

4. Discussion

Generally, previous reports indicates that many viruses including foot-and-mouth disease viruses, influenza A virus subtype H5N1, severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus (SARSCoV) and human bocavirus, preferentially use C and G-ended codons (Zhao et al., 2008, Zhong et al., 2007, Zhou et al., 2005). It is unclear how the EU and US serotypes of PRRSV influence codon usage pattern to date. In this study, it is revealed that preferentially used codons are C, G and U-ended codons for the PRRSV, especially, four amino acids (Cys, His, Phe and Pro) preferentially used U-ended codons. One possible explanation for why PRRSV has three types of optimal codons, compared with other RNA viruses mentioned above was that more types of optimal codon is advantageous to PRRSV which need to replicate efficiently in host cells with potentially distinct codon preferences.

Although PRRSV could not been classified into US and EU serotypes by the RSCU values of all ORFs, some reports on the genetic analysis of the ORF5 could help us understand the genetic relationships among different isolates (Cha et al., 2006, Chen et al., 2006, Mateu et al., 2006). It is known that ORF5 which encodes the major envelope glycoprotein (GP5) is one of the main immunogenic proteins of PRRSV and is the leading target for the development of the genetic engineering vaccines against PRRS. However, due to striking genetic and antigenic variability among different PRRSV isolates, GP5 of a strain has a negative effect on the cross-protection efficiency against heterologous PRRSV strains (Kim and Yoon, 2008, Meng, 2000). The synonymous codon usage pattern of ORF1a or ORF5 has the ability to distinguish between US and EU serotypes. To some degree, it seems that codon usage variation of ORF1a has a better ability to distinguish strain types than that of ORF5, and the latter has a remarkable characteristic of genetic variability within both homologous serotype and heterologous serotypes. However, the synonymous codon usage pattern of ORF3 does not group strains into US or EU serotype obviously, possibly suggesting that GP3 contains a common biological function in both serotypes. The result is consistent with some viewpoints about GP3 of PRRSV (Meulenberg et al., 1995). One possible explanation is that biological function of different viral products is developed by mutational pressure, rather than natural selection. It is also reported that there was a relationship between geographical location of sample origin and the genetic diversity of PRRSV (Stadejek et al., 2006). In this study, although synonymous codon usage variation fails to reflect that a geographical factor, the index has an obvious effect on codon usage pattern. This result is in agreement with the report by Pesch et al. (2005).

As for RNA viruses, the major factor of shaping codon usage patterns appears to be mutation pressure rather than natural selection (Zhao et al., 2008, Zhong et al., 2007, Zhou et al., 2005). To reveal the main force driving codon usage variation, it was found that codon usage bias was strong correlated with overall genomic (G + C) content, implying that composition constraint under mutational pressure rather than natural selection for specific coding triplets (Shackelton et al., 2006). Naya et al. (2001) found that in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii genome with high (G + C) content, there was no evidence that composition constraint played a role in shaping codon usage pattern. The results indicated that there were two main forces, namely, natural selection and mutational pressure, existing in the process of evolution. In this study, each base composition at the third position of synonymous codon was always correlated to the other base composition (Table 4). The fact that (G + C) content varies in a similar way at all codon positions is usually assumed to be the result of mutational bias. The fact that (G + C) content varies in a similar way at all codon positions is usually assumed to be the result of mutational pressure. A general mutational pressure, which affects the whole genome would certainly account for the majority of the codon usage has been reported among some RNA viruses. Since mutation rates of RNA viruses are much higher than those DNA viruses (Jenkins and Holmes, 2003), it is understandable that mutation pressure plays a key role in shaping the synonymous codon usage pattern in different ORFs of the 13 PRRSV strains included in this study. In addition, the general association between codon usage indices and composition constraint shows that mutational pressure plays an important role in determining codon usage variation of PRRSV, which is supported by the highly significant correlation between codon usage indices and A3%, U3%, G3%, C3% (Table 5). Although the codon usage indices is strong correlated with composition constraint (C3 + G3)% has stronger correlation with values than , implying that it has no real correlation with codon usage indices. The fluctuation of (C3 + G3)% does not reflect C3% and G3% and (C3 + G3)% may not always present the degree of composition constraint, so the fluctuation of each nucleotide composition needs to be analyzed further. Sequence analysis indicated PRRSV achieve evolution through random mutation and intragenic recombination (Kapur et al., 1996, Meng et al., 1995, Murtaugh et al., 1995, Nelsen et al., 1999). Taken together, mutational pressure is one of the main factors responsible for the variation of synonymous codon usage among ORF coding sequences in PRRSV.

The codon usage bias for synonymous codon in different ORFs of PRRSV shows different feature in the study. Among these ORFs, each includes some amino acids with strong selective discrepancy and some synonymous codons for a particular amino acid has been used preferentially. It seems that the codon usage discrepancy for some synonymous codon may serve as a potential genetic marker. Nielsen et al. (2001) examined the alternative of synonymous and non-synonymous amino acids in ORF1 of PRRSV and pointed out that there was a stronger selective pressure for amino acid conservation during spread in host animal. Storgaard et al. (1999) found that non-synonymous nucleotide mutations in ORF7 of PRRSV were not stronger than ORF5. These findings suggest that gene function and mutational pressure likely affect codon usage variation. In addition, the effect of natural translation selection in shaping synonymous codon usage is not observed in this study and this is consistent with those previous reports (Biro, 2008, Gu et al., 2004, Levin and Whittome, 2000, Zhou et al., 2005). These results probably assist us in understanding various factors influencing evolution of PRRSV.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in parts by grants from International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (No. 2010DFA32640) and Science and Technology Key Project of Gansu Province (No. 0801NKDA034). This study was also supported by National Natural Science foundation of China (No. 30700597).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2010.04.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Fig. S1.

A plot of the f1′ and the f2′ of each ORF in PRRSV.

Fig. S2.

The plots of synonymous codon usage indices for ORF1a, ORF4, ORF5, ORF7. The plots of US serotypes with filed of the same color show solid shape, in contrast, the plots of EU serotype with the same color to the same ORF show hollow shape.

Fig. S3.

The overlay scatter-plot of the total content of each nucleotide and the content of the same nucleotide at the synonymous third position of sense codon. Y axis standards for A%, U%, C%, G%, (C3 + G3)%, respectively; X axis standards for A3%, U3%, C3%, G3%, (C3 + G3)% respectively.

Fig. S4.

The relationship of codon usage bias and synonymous codon usage. The more CUB absolute value for synonymous codon is, the stronger the discrepancy of synonymous codon is.

Fig. S5.

Synonymous codons and amino acids. Distribution of the CUB of a synonymous codon for a particular amino acid. The CUB value is calculated by the formula mentioned above, and sorted in ascending order.

References

- Bautista E.M., Goyal S.M., Yoon I.J., Joo H.S., Collins J.E. Comparison of porcine alveolar macrophages and CL2621 for the detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus and anti-PRRS antibody. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1993;5:163–165. doi: 10.1177/104063879300500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfield D.A., Nelson E., Collins J.E., Harris L., Goyal S.M., Robison D., Christianson W.T., Morrison R.B., Gorayca D., Chladek D. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1992;4:127–133. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro J.C. Does codon bias have an evolutionary origin? Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2008;5:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Nidovirales: a new order comprising Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae. Arch. Virol. 1997;142:629–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha S.H., Choi E.J., Park J.H., Yoon S.R., Song J.Y., Kwon J.H., Song H.J., Yoon K.J. Molecular characterization of recent Korean porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) viruses and comparison to other Asian PRRS viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;117:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Liu T., Zhu C.G., Jin Y.F., Zhang Y.Z. Genetic variation of Chinese PRRSV strains based on ORF 5 sequence. Biochem. Genet. 2006;44:421–431. doi: 10.1007/s10528-006-9039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J.E., Benfield D.A., Christianson W.T., Harris L., Hennings J.C., Shaw D.P., Goyal S.M., McCullough S., Morrison R.B., Joo H.S., Gorcyca D., Chladek D. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus (isolated ATCC-2332) in North American and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1992;4:117–126. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conzelmann K.K., Visser N., van Woensel P., Tiel H.J. Molecular characterization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, a member of the Artervirus group. Virology. 1993;193:329–339. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar K.A., Goodenbour J.M., Pan J. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS. Genet. 2006;2:2107–2115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewens W.J., Grant G.R. Springer; New York: 2001. Statistical Methods in Bioinformatics. [Google Scholar]

- Grantham R., Gautier C., Gouy M., Mercier R., Pave A. Codon catalog usage and the genome hypothesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:r49–r62. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.1.197-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W.J., Zhou T., Ma J.M., Sun X., Lu Z.H. Analysis of synonymous codon usage in SARS coronavirus and other viruses in the Nidovirales. Virus Res. 2004;101:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins G.M., Holmes E.C. The extent of codon usage bias in human RNA virus and its evolutionary origin. Virus Res. 2003;92:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe I.T. 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2002. Principal Component Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur V., Elam M.R., Pawlovich T.M., Murtaugh M.P. Genetic variation in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates in the Midwestern United States. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77:1271–1276. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S., Mrázek J. What drives codon chices in human genes? J. Mol. Biol. 1996;262:459–472. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keffaber K.K. Reproductive failure of unknown etiology. Am. Assoc. Swine Pract. News. 1989;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kim W.I., Yoon K.J. Molecular assessment of the role of envelope-associated structural proteins in cross neutralization among different PRRS viruses. Virus Genes. 2008;37:380–391. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesnik T., Solomovici J., Deana A., Ehrlich R., Reiss C. Ribosome traffic in E. coli and regulation of gene expression. J. Theor. Biol. 2000;202:175–185. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1999.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin D.B., Whittome B. Codon usage in nucleopolyhedroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2000;81:2313–2325. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-9-2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A.T., Sharp P.M. Evolution of codon usage patterns: the extent and nature of divergence between Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5289–5295. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.20.5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loula T. Mystery pig disease. Agric. Practice. 1991;12:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mardia K.V., Kent J.T., Bibby J.M. Academic Press; New York: 1979. Multivariate Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Martin A., Bertranpetit J., Oliver J.L. Variation in G + C content and codon choice: differences among synonymous codon groups in vertebrate genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6181–6189. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateu E., Diaz I., Darwich L., Casal J., Martin M., Pujols J. Evolution of ORF5 of Spanish porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strains from 1991 to 2005. Virus Res. 2006;115:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.J. Heterogeneity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: implications for current vaccine efficacy and future vaccine development. Vet. Microbiol. 2000;74:309–329. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.J., Paul P.S., Halbur P.G., Lum M.A. Phylogenetic analysis of the putative M (ORF6) and N (ORF7) genes of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV): implication for the existence of two genotypes of PRRSV in the USA. Arch. Virol. 1995;76:745–755. doi: 10.1007/BF01309962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg J.J.M., Hulst M.M., de Meuer E.J., Moonen P.L.J.M., den Besten A., de Kluyver E.P., Wensvoort G., Moormann R.J.M. Lelystad virus, the causative agent of porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome (PEARS) is related to LDV and EAV. Virology. 1993;192:62–74. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg J.J.M., Petersen-Den B.A., De Kluyver E.P., Moormann R.J., Schaaper W.M., Wensvoort G. Characterization of proteins encoded by ORFs 2 to 7 of Lelystad virus. Virology. 1995;206:155–163. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(95)80030-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh M.P., Elam M.R., Kakach L.T. Comparison of the structural protein coding sequences of the VR-2332 and Lelystad virus strains of PRRS virus. Arch. Biol. 1995;140:1451–1460. doi: 10.1007/BF01322671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya H., Romero H., Carels N., Zavala A., Musto H. Translational selection shapes codon usage in the GC-rich genome of Chlamydomonas reinharatii. FEBS Lett. 2001;501:127–130. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen C.J., Murtaugh M.P., Faaberg K.S. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus comparison: divergent evolution of two continents. J. Virol. 1999;72:270–280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.270-280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A., Oleksiewicz M.B., Forsberg R., Stadejek T., Bøtner A., Storgaard T. Reversion of a live porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus vaccine investigated by parallel mutations. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:1263–1272. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-6-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesch S., Meyer C., Ohlinger V.F. New insights into the genetic diversity of European porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Vet. Microbiol. 2005;107:31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagemann P.G.W., Moennig V. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, equine arteritis virus, and simian hemorrhagic fever virus: a new group of positive-stranded RNA viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1992;41:99–192. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelton L.A., Parrish C.R., Holmes E.C. Evolutionary basis of codon usage and nucleotide composition bias in vertebrate DNA viruses. J. Mol. Evol. 2006;62:551–563. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadejek T., Oleksiewicz M.B., Potapchuk D., Podgorska K. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strains of exceptional diversity in Eastern Europe support the definition of new genetic subtypes. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:1835–1841. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P.M., Li W.H. Codon usage in regulatory genes in Escherichia coli does not reflect selection for ‘rare’ codon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:7737–7749. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.19.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp P.M., Tuohy T.M., Mosurski K.R. Codon usage in yeast: cluster analysis clearly differentiates highly and lowly expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:5125–5143. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.13.5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storgaard T., Oleksiewicz M., Bøtner A. Examination of the selective pressures on a live PRRS vaccine virus. Arch. Virol. 1999;144:2389–2401. doi: 10.1007/s007050050652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T., Ding D., Tao X., Dafu D. The relationship between synonymous codon usage and protein structure. FEBS Lett. 1998;434:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensvoort G., Terpstra C., Pol J.M.A., Ter Laak E.A., Bloemraad M., De Kluyver E.P., Kragten C., van Buiten L., den Besten A., Wagenaar F. Mystery swine disease in the Netherlands; the isolation of lelystad virus. Vet. Q. 1991;13:121–130. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1991.9694296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Zhang Q., Liu X.L., Wang X.M., Zhang H.L., Wu Y., Jiang F. Analysis of synonymous codon usage in 11 Human Bocavirus isolates. Biosystems. 2008;92:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J.C., Li Y.M., Zhao S., Liu S., Zhang Z. Mutation pressure shapes codon usage in the GC-rich genome of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Virus Genes. 2007;35:767–776. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0159-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T., Gu W.J., Ma J.M., Sun X., Lu Z.H. Analysis of synonymous codon usage in H5N1 virus and other influenza A viruses. Biosystems. 2005;81:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T., Sun X., Lu Z.H. Synonymous codon usage in environmental Chlamydia UWE25 reflects an evolution divergence from pathogenic chlamydiae. Gene. 2006;368:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J.-h., Zhang J., Ding Y.-z., Chen H.-t., Ma L.-n., Liu Y.-s. Characteristics of codon usage bias in two regions downstream of the initiation codons of foot-and-mouth disease virus. BioSystems. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]