Abstract

Radiology in low- and middle-income (developing) countries continues to make progress. Research and international outreach projects presented at the 2015 annual RAD-AID conference emphasize important global themes, including (1) recent slowing of emerging market growth that threatens to constrain the advance of radiology, (2) increasing global noncommunicable diseases (such as cancer and cardiovascular disease) needing radiology for detection and management, (3) strategic prioritization for pediatric radiology in global public health initiatives, (4) continuous expansion of global health curricula at radiology residencies and the RAD-AID Chapter Network’s participating institutions, and (5) technologic innovation for recently accelerated implementation of PACS in low-resource countries.

Key Words: Radiology, developing countries, radiology readiness, PACS readiness, sustainability, radiology outreach

Introduction

The field of global health remains focused on the interface among poverty, economic disparity, and health outcomes. As a capital and knowledge-intensive specialty, radiology’s role in global health has been largely shaped by (1) limited available capital impeding hardware acquisition, (2) limited education in radiologic services, and (3) limited market dynamics for sustaining availability of radiology professionals.

Radiology is making significant strides in global health to address these limitations as more US-based programs launch global outreach programs and integrate public health training for residents. Current World Health Organization (WHO) statistics and estimates still place radiology as inadequate, absent, and/or inaccessible to approximately half the world’s population, especially cross-sectional imaging such as CT and MRI [1]. Ultrasound is making stronger gains worldwide as manufacturers offer lower cost units with larger distribution networks in low- and middle-income (developing) countries. Low-cost radiography is mostly in prototype form or in limited availability from specialized vendors. PACS are largely absent in resource-limited countries except for open-source DICOM viewers without accessible archives, where digital scanning hardware is generally left disconnected from centralized digital storage networks.

In this article, we address the multifaceted, ongoing nature of radiology health care disparity throughout the world on the basis of the projects, programs, and presentations at the 2015 RAD-AID conference, cosponsored by the WHO. The forum discussion approaches radiology disparity in terms of economic development, public health approaches, clinical model formulation, technologic innovation, and educational strategies for international medical volunteers, as well as in-country radiology professionals. The fundamental aim of RAD-AID and this conference is to increase and improve radiology for poor and low-resource countries 2, 3, 4.

Economic Development for Global Radiology

Recent economic trends in the developing world are challenging the advancement of radiology in low- and middle-income countries. Over the past year, economic growth has slowed throughout the developing world, with destabilized prices of natural resources [5]. Because radiology is a vital part of health care systems, slowed economic growth threatens to impede the development of health care systems in these countries. In parts of Asia and Africa, where economic growth was stronger before 2015, the more recent economic trends should be considered as an important factor for how further health technology investments are made. One example is RAD-AID’s ongoing Cancer Imaging and Treatment Initiative in western China, in collaboration with the American Society of Radiologic Technologists Foundation, in which the program bridges radiologic imaging with radiation therapy to advance multidisciplinary care. A key avenue of Chinese health care development is to add more interdisciplinary resources in cancer care, so that imaging, radiation, medical oncology, nursing, vascular access, and social work can be further integrated. Such an initiative for adding more stakeholders and strengthening interdisciplinary bridges will require greater investment in the local health care system. In consideration of these needs, RAD-AID is proposing efforts to provide interventional radiology support for chemotherapy port placements and radiation therapy education in areas of western China.

RAD-AID has also worked with the banking sector of East Africa and West Africa for the past three years to support radiology-training programs. Recent economic trends, however, have weakened confidence in banking systems for providing educational loans to African students. As these efforts continue from RAD-AID and other radiology nonprofit outreach organizations, international economics and market dynamics will remain as important variables influencing the availability of resources for health care delivery.

Another theme in the economic development of international radiology is the response to natural disasters. Natural disasters result in the massive loss and disabling of human life, in addition to large economic losses from destroyed infrastructure. Historically, radiology has not played a vital role in natural disaster response. However, RAD-AID mobilized a response to the Nepal earthquake in April 2015, with support from the American Society of Radiologic Technologists Foundation and the British Society and College of Radiographers, with follow-up support from the ACR Foundation. Recruiting across its base of nearly 4,500 volunteers, RAD-AID organized a team of six radiology professionals to work in the Kathmandu region for three to four weeks immediately after the earthquake in 2015. Established goals for the crisis-response team included assessing trauma victims, analyzing damage to health infrastructure, conducting outreach visits to isolated communities, and planning postearthquake reconstruction efforts. This form of organized response sets up the opportunity for improved disaster-relief efforts from the radiology community, particularly to assess and possibly correct radiology infrastructure damage, help with trauma victims, and plan reconstruction. These disaster-response planning functions are currently under way, with initial collaboration between the ACR Foundation and RAD-AID.

Education

To achieve educational progress in international radiology, RAD-AID started the Chapters Network in 2012, which has grown to include 46 ACGME-accredited health institution academic centers at the time of this writing. The network has implemented a common curriculum of global health training for radiology residents that is uniformly applicable across the participating institutions and enables chapter members to create interinstitutional chapter teams serving in RAD-AID’s international programs [1].

An important trend buttressing chapter development is the formulation of international elective rotations at academic training programs. The key administrative barrier for elective rotations has been graduate medical education approval for radiology residents to work abroad. The principal educational challenge is how to best make these rotations productive as training experiences for the residents. The RAD-AID chapters at Emory University and New York-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center have implemented models of international elective rotations in their residency programs, located primarily in Ethiopia at the time of this writing 6, 7. RAD-AID adds resources to elective residency rotations via grants, technology and PACS support, project guidance, and educational materials, to maximize the impact of residents working in underserved areas.

Central to the objective of formulating international radiology electives is the question of what an overseas radiology resident should (and should not) do. The conventional practice in the United States is that trainees interpret scans under attending radiologists’ supervision via hospital and outpatient rotations. But in the developing world, where PACS are generally absent, technical quality is widely insufficient, radiation safety is unclear, and radiology reporting systems are often unreliable, residents may have unclear roles that are not well defined in comparison with precisely delineated US standards for domestic clinical training rotations. Instead, an international rotation should be established with clear learning objectives that have more relevance to project preparation, understanding workflows in resource-limited locations, interpreting image quality in resource-constrained contexts, and tracking what happens to reported imaging results in follow-up patient care. Moreover, the international elective is not about passively receiving instruction but having radiology residents actively perform a dynamic project that contributes to the growth of radiology in a region, community, or country. Examples include recent RAD-AID sites having residents deploy online learning management systems (Nicaragua, Haiti), implement PACS platforms (Ethiopia, Ghana, Nepal, Haiti, Nicaragua), participate in demonstrations of procedures (Nicaragua, Guyana, Ethiopia, Haiti, Malawi), or perform research on reporting methods and patient compliance with image-based screenings (Bhutan, India). At the conclusion of such project trips, RAD-AID generally requires a written report from residents so that the accomplished work and observed challenges can provide a foundation for future residents to build upon.

To broaden the availability of structured educational training in project development for international radiology outreach, RAD-AID is now offering the RAD-AID Certificate of Proficiency in Global Health Radiology, a structured program for technologists, physicians, nurses, and those interested in public health or international policy. The program is in its second year in 2016 and runs six months in duration with interactive participation from three to eight registrants learning topics of international radiology project development [8].

The educational needs of medical students interested in radiology and global health have become a paramount issue for radiology training in the last year. Because global health may be a strong focus of interest for medical students considering a radiology residency, it is important for medical schools to offer a means to obtain such experience so that highly qualified medical students do not avoid radiology under the misperception that radiology does not have a robust international health track. Accordingly, RAD-AID and the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons launched an elective course (set to start in 2016-2017) to be offered to medical students, in which the clerkship will run four weeks (after completing a general radiology course). The course includes didactic teaching from radiology faculty on global health, and a RAD-AID project overseas with a RAD-AID team for concrete hands-on experience. Course objectives include learning project design strategies, understanding the complex relations between health technologies and poverty, studying health care disparities, and learning how radiology fits into low-resource environments as a critical resource for health care delivery.

Public Health

Public health and radiology have an evolving relationship in the international context. As public health entails medicine at the population level to ensure prevention and minimized mortality and morbidity, radiology-based screening and diagnostic measures provide an important metric for public health surveillance and intervention. An important initiative taken on in the past year by RAD-AID and partners has been an emphasis on pediatric imaging. Of the approximate 3 billion to 4 billion in the world lacking adequate access to radiologic services, approximately 500 million to 1 billion are children. Because children have the highest risk for life-years lost from absent medical care, the priority of providing health services for children is evident 9, 10. In 2015, the International Day of Radiology, organized by the RSNA, ACR, and European Society of Radiology with numerous professional society supporters, featured pediatric radiology as the central focus. RAD-AID launched five new programs in pediatrics in 2014 and 2015, including country sites in Laos, Haiti, Nicaragua, Malawi, and Ghana. This regular deployment of pediatric radiologic technologists, sonographers, and radiologists strengthens methods of imaging children, with safety and quality as primary drivers for improving outcomes.

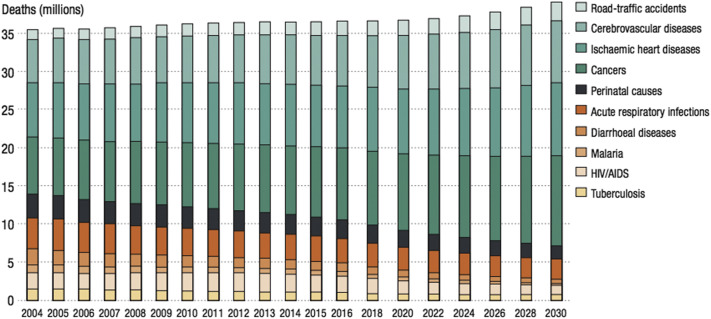

Another important trend in public health for radiology is striking a balance between targeting communicable (infectious) versus noncommunicable diseases [11]. The WHO reports that there is currently a worldwide decline in communicable diseases, which is due mainly to the prevention of infectious disease transmissions via globally improved sanitation, water quality, and vaccinations. This trend is sometimes difficult to fully appreciate given the high public visibility of dangerous outbreaks, such as Zika, Ebola virus disease, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and influenza in the past five years. Nevertheless, the WHO reports that the decline in communicable diseases occurs in tandem with a rising incidence and prevalence of noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and trauma (Fig. 1 ) [12]. The noncommunicable disease segment, however, is well known to be more radiology dependent for diagnosis and care, using radiologic techniques such as cancer staging, cardiovascular angiography, and plain-film or CT management of traumatic injury. As increased attention is warranted for noncommunicable disease care, it is essential that radiology play a heightened role in the international context. Historically, humanitarian aid efforts during natural disasters, epidemics, and pandemics have not involved intense radiology participation, but shifting trends toward chronic care and noncommunicable disease patterns certainly supports progression toward radiologic imaging in these resource-limited contexts.

Fig 1.

Number of deaths attributable to select noncommunicable and communicable diseases, 2004 to 2030, based on World Health Organization (WHO) data and projections. The increasing proportion of deaths attributable to noncommunicable diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, suggests a heightened role for radiology in diagnosis and care.

(Reprinted from WHO, with permission, available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/.)

Technologic Innovation

Technologic innovation is an important part of how radiology can make advances in developing countries. One approach has been to develop low-cost technologic advances that can substitute for higher cost technologies used in high-resource health systems. One drawback of this approach is that health practitioners in low-resource nations with training in advanced health care systems may express reservations adopting low-cost alternatives if there are observable differences in quality and practice patterns (interpretations, patient management, radiation safety, etc). Nevertheless, the financial barrier for capital-intensive modalities continues to be a significant obstacle in most modalities, such as CT, MRI, and PET. Lower cost hardware, such as ultrasound, could increase in utilization and access in resource-limited countries. However, the lower cost of ultrasound coupled with resulting higher access is partially offset by the fact that ultrasound is very operator dependent, necessitating well-trained (often scarce) personnel for image acquisition and interpretation.

A critical missing element of international radiology development is PACS. RAD-AID’s Radiology-Readiness Assessments across 15 countries showed a consistent absence of PACS platforms and related digital health IT. In many instances, even when digital hardware was available at an institution, the necessary infrastructure for digital connectivity was absent, namely, DICOM licenses and high-speed local area networks. The common practice, in RAD-AID’s on-site experience, has been that imaging facilities in low-resource countries would use a free open-source DICOM viewer to download images to a computer from a CD or DVD or view images directly on workstations tied to the modalities. In terms of storage, these DICOM files are then either saved to small local hard drives or flash drives and/or printed to film for physical filing. Therefore, even if there is digital imaging available at a low-resource health facility with computers for image viewing, the entire structure for health IT is still lacking.

RAD-AID approached this problem aggressively in 2015, launching the International Imaging Informatics Initiative, in partnership with Merge Healthcare (now an IBM company). Donations of Merge software licenses enabled RAD-AID teams (with Merge support) to install PACS at health institutions in Nicaragua, Ghana, Nepal, and Haiti, with plans to perform installations in Tanzania and Ethiopia at the time of this writing. The essential data collection preparation for these installations is the RAD-AID PACS-Readiness Assessment tool, adapted from RAD-AID’s more comprehensive Radiology-Readiness Assessment tool, to engage in preinstallation data analysis on the availability of necessary health IT resources 2, 3, 4. This tailored assessment contains questions related to the availability of Internet and intranet connections, computer workstations, servers, DICOM licenses, scanner specifications, and power integrity. Advanced knowledge of this information before installation allows RAD-AID to plan the most appropriate site-specific architecture and maximize the success of installation. For example, some institutions are better suited for a mini-PACS platform given limited resources and experience with radiology informatics. However, at sites with more experience with radiology informatics, such as Ghana, where RAD-AID implemented a PACS platform at Korle Bu Hospital in 2013, implementing a comprehensive PACS solution is more appropriate. Assessing the learning curve and readily available IT resources maximizes the institutional adoption of PACS platforms.

Another vital element for archiving information in resource-limited countries is the incorporation of cloud architectures rather than solely onsite storage. In Nepal, RAD-AID partnered with DICOM Grid to offer additional cloud storage for images at the National Academy of Medical Sciences Bir Hospital, in contrast to using primarily local physical storage as with PACS in Ghana. Therefore, having a spectrum of deployable architectures in the developing world is vital for flexibly designing a viable solution (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

PACS implementation stages

| Stage 1 | Mini-PACS system with linked workstations |

| Stage 2 | Open-source archive with webserver/viewer or mini-PACS system with cloud-based PACS storage |

| Stage 3 | Full PACS platform with enterprise VNA or local PACS storage |

Note: These stages of implementation represent progressive levels of technical complexity that factor in site infrastructure, hardware constraints, study volume, available personnel and clinical use. Each stage has varying implementation requirements that are minimal at stage 1 and most comprehensive at stage 3. VNA = vendor-neutral archive.

Conclusions

The RAD-AID conference continues to discuss and offer radiology approaches for imaging in low- and middle-income countries where poor access to resources is an ongoing threat to health outcomes. Radiology is a vital link across many medical and surgical specialties, in which the absence of imaging is a reverberating gap in essential health care chains. This year’s dialogue, emphasizing pediatric imaging, shifting trends in noncommunicable diseases, technologic innovation and expansion for PACS, as well as progressing efforts to improve global health training for residents, brings to light the ongoing advances that radiology is making in international health contexts. Consistent themes in the projects and plans highlight the importance of preproject data collection and assessment, such as through the Radiology-Readiness Assessment (since 2009) and PACS-Readiness Assessment (since 2015) tools. Such planning improves project structure for efficient radiology deployment and maximizes radiologic impact to resource-scarce health care systems.

Take-Home Points

-

■

The RAD-AID conference continues to discuss and offer radiology approaches for imaging in low- and middle-income countries where poor access to resources is an ongoing threat to health outcomes.

-

■

Shifting trends toward chronic care and noncommunicable disease patterns supports progression toward radiologic imaging in these resource-limited contexts.

-

■

Preproject data collection and assessment improves project structure for efficient radiology deployment and maximizes radiologic impact to resource-scarce health care systems.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to the material discussed in this article.

Contributor Information

Daniel J. Mollura, Email: dmollura@rad-aid.org.

RAD-AID Conference Writing Group:

Geraldine Abbey-Mensah, James Borgstede, Dorothy Bulas, George Carberry, Danielle Canter, Farhad Ebrahim, Joanna Escalon, Lauren Fuller, Carrie Hayes, Trent Hope, Andrew Kesselman, Niranjan Khandelwal, Woojin Kim, Jonathan Mazal, Eralda Mema, Miriam Mikhail, Daniel J. Mollura, Natasha Monchil, Robert Morrow, Hammed Ninalowo, Hansel Otero, Shilpen Patel, Seth Quansah, Michael Reiter, Klaus Schonenberger, Peter Shaba, Tulika Singh, Garshasb Soroosh, Rebecca Stein-Wexler, Tiffani Walker, Andrew Woodward, Mindy Yang, and Michael Yannes

Appendix

RAD-AID Writing Group Contributors (Listed Alphabetically)

Geraldine Abbey-Mensah, MD, James Borgstede, MD, Dorothy Bulas, MD, George Carberry, MD, Danielle Canter, BS, Farhad Ebrahim, MD, Joanna Escalon, MD, Lauren Fuller, BS, RT(R), Carrie Hayes, MHS, PA-C, RDMS, RVT, Trent Hope, BS, Andrew Kesselman, MD, Niranjan Khandelwal, MBBS, Woojin Kim, MD, Jonathan Mazal, MS, RRA, RT(R)(MR), Eralda Mema, MD, Miriam Mikhail, MD, Daniel J. Mollura, MD, Natasha Monchil, RT(R), Robert Morrow, MD, MPH, FACPM, Hammed Ninalowo, MD, Hansel Otero, MD, Shilpen Patel, MD, Seth Quansah, BSc, Michael Reiter, MD, Klaus Schonenberger, PhD, Peter Shaba, RT(R), Tulika Singh, MBBS, Garshasb Soroosh, Rebecca Stein-Wexler, MD, Tiffani Walker, RT(R), Andrew Woodward, MA, RT(R)(CT)(QA), Mindy Yang, MD, Michael Yannes, MD.

References

- 1.Mollura D.J., Lungren M.P. Springer; New York: 2014. Radiology in global health: strategies, implementation, and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollura D.J., Mazal J., Everton K.L., RAD-AID Conference Writing Group White paper report of the 2012 RAD-AID Conference on International Radiology for Developing Countries: planning the implementation of global radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10:618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mollura D.J., Shah N., Mazal J., RAD-AID Conference Writing Group White paper report of the 2013 RAD-AID Conference: improving radiology in resource-limited regions and developing countries. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11:913–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culp M., Mollura D.J., Mazal J., RAD-AID Conference Writing Group 2014 RAD-AID Conference on International Radiology for Developing Countries: the road ahead for global health radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gough N. China’s slowdown raises questions about long-term growth. The New York Times. November 4, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escalon J, Renjen P. A step-by-step guide to creating an elective rotation abroad for radiology residents. Available at: http://www.rad-aid.org/wp-content/uploads/Guide-to-Creating-an-Elective-Rotation-Abroad-for-Radiology-Residents.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- 7.Tahvildari A.M., Atnafu A., Cosco D., Acosta A., Gupta D., Hudgins P.A. Global health and radiology: a new paradigm for US radiology resident training. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culp M. RAD-AID Certificate of Proficiency in Global Health Radiology 2015. Available at: http://www.rad-aid.org/programs/global-health-radiology-certificate-proficiency/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- 9.Strouse P.J. Outreach in pediatric radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:635. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-2999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg M. Global child health: burden of disease, achievements, and future challenges. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007;37:338–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global Burden of Disease Study Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. World health statistics. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2013_Full.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2016.