Highlights

-

•

4.2% of PCR-negative respiratory specimens were positive in viral culture.

-

•

Half of the recovered viruses were not part of the multiplex PCR panel.

-

•

Routine viral culture on PCR-negative respiratory specimens had minimal clinical impact.

-

•

The findings of this study may help resource utilization in the virology laboratory.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Respiratory tract infection, Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, Diagnosis, Viral cell culture

Abstract

Background

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the reference standard for respiratory virus testing. However, cell culture may still have added value in identifying viruses not detected by PCR.

Objectives

We aimed to estimate the yield and clinical impact of routine respiratory virus culture among children with a negative PCR result.

Study design

A retrospective cohort study was performed from Jan. 2013 to Sept. 2015. Respiratory samples from hospitalized or immunocompromised patients <18 years old were routinely inoculated on traditional tube cell culture monolayers if they tested negative by a PCR assay for 12 respiratory viruses. We studied patients with a respiratory specimen negative by PCR and positive by culture. Duplicates and samples of sold services were excluded. Data on demographics, clinical history, laboratory findings, and patient management were collected from patients’ charts. Descriptive and multivariate statistics were performed.

Results

Overall, 4638 PCR-negative samples were inoculated in cell culture. Of those, 196 (4.2%) were cell culture positive, and 144 met study inclusion criteria. Most subjects (81.9%) were hospitalized. Mean age was 2.4 ± 3.4 years. The viruses most frequently isolated were cytomegalovirus (33.3%) and enteroviruses (19.4%). Cell culture results prompted a change in management in 5 patients (3.5%), all of whom had acyclovir initiated for localized HSV-1 infection. Four of these had skin or mucosal lesions that could be sampled to establish a diagnosis.

Conclusion

In children, routine viral culture on respiratory specimens that were negative by PCR has low yield and minimal clinical impact.

1. Background

Viral respiratory infection is a leading cause of hospitalizations, acute care visits, and antibiotic overuse in children [1]. The diagnosis is confirmed by identification of a respiratory virus in a respiratory specimen [2]. Traditional diagnostic methods include viral isolation by cell culture and detection of viral antigens by immunofluorescence. The superior sensitivity of molecular methods such as reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has led to their increased use in clinical laboratories [3], [4]. Still, some authors suggest performing viral culture in a backup role in respiratory specimens from high-risk populations to detect viruses that are not part of the RT-PCR assay or whose genomes have mutations that may lead to false-negative RT-PCR results [5], [6]. However, the implementation of a second diagnostic step, i.e., viral culture after a negative RT-PCR result, is associated with additional costs and unknown effect on clinical management.

2. Objectives

We aimed to estimate the yield of routine respiratory virus culture among children with a negative PCR and to describe the impact of a positive cell culture result on their care.

3. Study design

We performed a single-center retrospective cohort study at the Montreal Children’s Hospital of the McGill University Health Centre (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) from Jan. 2013 to Sept. 2015. The study population included all patients <18 years old with a viral culture performed on a respiratory specimen that had tested negative by multiplex PCR. Duplicate samples were excluded (>1 viral culture for the same patient within 7 days or during the same illness episode).

All respiratory virus specimens submitted to the clinical virology laboratory were tested using a laboratory-developed multiplex real-time PCR assay for 12 viruses (Influenza A/B, Parainfluenza 1/2/3, RSV, Adenovirus, Coronavirus 229E/OC43, Human Metapneumovirus, Enterovirus, and Rhinovirus) [7], [8]. The mean turnaround time for the PCR assay was ∼9 h [8]. Respiratory samples from hospitalized or immunocompromised patients that tested negative by PCR were routinely inoculated on traditional tube cell culture monolayers (RMK, A-549, and MRC-5 cell lines; Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA). Cell culture tubes were observed for cytopathic effect three times per week and incubated for a total of 16 days. Hemadsorption was performed in one of the two RMK tubes between days 6 and 8.

Patient charts were reviewed to collect data on patient demographics, clinical history, significant underlying chronic co-morbidities, and medical management.

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. In addition, clinical factors associated with the isolation of a respiratory virus (compared to other viruses) were assessed by logistic regression. Multivariate logistic regression model selection was guided by Akaike information criterion.

4. Results

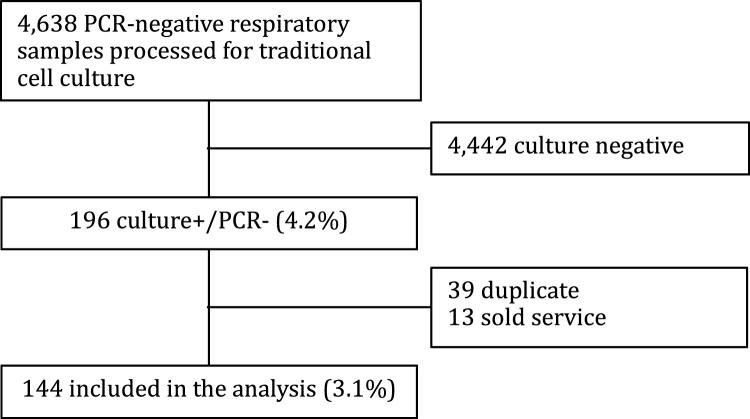

During the study period, 4638 respiratory specimens were processed for viral culture (Fig. 1 ). Of those, 196 (4.2%) specimens were culture+/PCR- and 144 (3.1%) specimens were included in the analysis. Excluded specimens included 39 duplicate samples and 13 sold service specimens (medical record unavailable). Subjects were mostly male (63.2%) and 118 (81.9%) were hospitalized (Table 1 ). Sixty-two patients (43.1%) were previously healthy and without known comorbidities. The mean age was 2.35 ± 3.4 years. Most specimens were nasopharyngeal samples (95%). The working diagnoses that most frequently prompted respiratory virus testing were unspecified febrile illness (30.6%) and lower respiratory tract infection (24.3%). There were 14 specimens (9.7%) that were processed for viral culture without clear indication.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patient samples.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical description of children with a negative PCR result and a positive viral culture.

| n = 144 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 91 (63.2%) |

| Female | 53 (36.8%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 2.35 ± 3.42 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.92 (0.24–2.64) |

| Sample type | |

| Nasopharyngeal aspirate or swab | 137 (95.14%) |

| Other (BAL and ETT aspirate) | 7 (4.86%) |

| Setting specimen collected in | |

| Medical and surgical inpatient units | 72 (50.0%) |

| Hematology-Oncology clinic or inpatient unit | 6 (4.16%) |

| Intensive care units | 29 (20.14%) |

| Emergency room | 24 (16.67%) |

| Other* | 13 (9.03%) |

| Admitted to hospital | 118 (81.94%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Healthy | 62 (43.06%) |

| Malignancy | 11 (7.64%) |

| Immunosuppressed state | 8 (5.56%) |

| Preterm | 14 (9.72%) |

| Sickle cell disease | 2 (1.39%) |

| Neuromuscular disease | 12 (8.33%) |

| Pulmonary disease | 17 (11.81%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 15 (10.42%) |

| Renal disease | 1 (0.69%) |

| Recurrent pneumonia | 6 (4.17%) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 9 (6.25%) |

| Other chronic diseases | 22 (15.28%) |

| Working diagnosis | |

| Upper respiratory infection | 23 (15.97%) |

| Lower respiratory infection | 35 (24.31%) |

| Febrile neonate | 12 (8.33%) |

| Unspecified febrile illness | 44 (30.56%) |

| Meningitis | 7 (4.86%) |

| Elective bronchoalveolar lavage | 5 (3.47%) |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 7 (4.86%) |

| Other | 11 (7.64%) |

| Chest x-ray findings | n = 77 |

| Normal chest x-ray | 16 (20.78%) |

| Consolidation | 18 (23.38%) |

| Pleural effusion | 5 (6.49%) |

| Perihiliar thickening | 38 (49.35%) |

| Air leak | 1 (1.30%) |

| Atelectasis | 14 (18.18%) |

| Hyperinflation | 6 (7.79%) |

| Pulmonary edema | 2 (2.60%) |

| Ground glass opacities | 1 (1.30%) |

| Lymphocyte count (References [9], [10]) | n = 112 |

| Low | 54 (37.5%) |

| Normal | 55 (38.19%) |

| High | 3 (2.08%) |

| Neutrophil count (References [9], [10]) | n = 112 |

| Low | 12 (8.33%) |

| Normal | 75 (52.08%) |

| High | 25 (17.36%) |

*Other: Day hospital, Day surgery, Respiratory clinic, Gastroenterology clinic, Infectious Diseases clinic.

SD = Standard deviation.

IQR = Interquartile range.

The mean turnaround time for a positive viral culture result was 9 days (Table 2 ). Viruses that were not part of the PCR assay comprised 53.5% of culture-positive specimens. The most frequently isolated viruses were cytomegalovirus (33.3%) and enteroviruses (19.4%).

Table 2.

Viruses isolated and mean result turnaround time (TAT) for cell culture.

| Viruses | n (%) | Mean TAT (days) |

|---|---|---|

| CMV | 48 (33.3%) | 8.0 |

| Enteroviruses | 28 (19.4%) | 7.9 |

| HSV-1 | 24 (16.7%) | 5.7 |

| Mumps | 1 (0.7%) | 6.0 |

| Respiratory viruses* | 43 (29.9%) | 12.8 |

*Adenovirus (1), Influenza B (1), Parainfluenza virus 1 (1), Parainfluenza virus 2 (3), Parainfluenza virus 3 (15), Parainfluenza virus 4 (4), Rhinovirus (15), and RSV (3).

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, factors independently associated with recovering a respiratory virus in cell culture (compared to other viruses) were a working diagnosis of upper or lower respiratory tract infection (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 4.88, 95% CI 1.87–12.76), malignancy comorbidity (aOR 5.71, 95% CI 1.38–23.71) and lymphopenia (aOR 2.91, 95% CI 1.13–7.52).

Cell culture results prompted a change in management in only 5 patients (3.5% of positive cultures, 0.1% of all cultures done), all of whom had acyclovir initiated for localized HSV-1 infection. Four of these had skin or mucosal lesions that could have been or were sampled to establish a diagnosis. One of the 5 patients was immunosuppressed (receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy), and none were neonates. Moreover, mumps, a reportable disease, was isolated in one patient in which mumps infection was not suspected. Communication with a patient’s family regarding culture results was documented in 4 instances where management had not been otherwise affected. No instances of cessation of antibiotics, discharge from hospital or initiation of antivirals for influenza or other respiratory viruses were observed in association with positive viral culture results.

5. Discussion

Molecular testing for respiratory viruses is highly sensitive [2], [11]. We observed that only 2% of PCR-negative pediatric respiratory samples were positive by cell culture for a virus in our RT-PCR panel. Moreover, positive cell culture results for any virus had little or no influence on clinical management.

The diagnostic yield of viral culture depends on several factors including the viral load, the quality of the respiratory specimen and cell lines, and the laboratory staff expertise [4]. A major drawback of traditional tube cell cultures is the long turnaround time, which can take between 2 days to 2 weeks to produce a result. For this reason, the clinical usefulness of the technique is guarded as the result may arrive too late to impact physician decision making [12]. In our study, only patients with HSV infection had their management changed due to viral culture. This could be explained in part by the shorter time to positivity for HSV and the availability of specific antiviral treatment (acyclovir). Another limitation of viral culture is that some respiratory viruses, e.g., group C rhinovirus, some group A coxackieviruses, coronaviruses, and polyomaviruses KIV and WUV, neither replicate nor produce identifiable cytopathic effect in standard cell culture lines [13], [14], [15].

Viral culture has the advantage of isolating and identifying a wide range of viruses rather than detecting specific viral genetic targets by RT-PCR. This may be important in the immunocompromised and newborn populations where viral infections not typically included in respiratory PCR assays (CMV and HSV) may be of clinical importance [3], [16]. Moreover, infections caused by viruses with genetic mutations may be falsely negative by PCR [3], [6], [17]. Viral culture may have additional advantages at the public health level for monitoring phenotypic antiviral susceptibilities, informing vaccine development, and identifying rare or novel strains. Because of the limitations and advantages of different diagnostic methods for respiratory viruses, a combination of methods is still recommended by some authors [5]. However, in our clinical laboratory, routine viral cultures from PCR-negative respiratory specimens had minimal impact on patient care.

While viral culture may rarely alter management, it can aid in identifying the causative viral agent in certain clinical scenarios. In our study, seven patients had a working diagnosis of meningitis; 3 of 7 grew enterovirus from the nasopharyngeal specimen (2 Echovirus and 1 Coxsackievirus B5). In those three patients without microbiological evidence of bacterial meningitis, one can infer that the likely cause of the aseptic meningitis was enterovirus.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the impact of routine viral culture in respiratory specimens that were negative by multiplex PCR. This single-center study is limited by its retrospective nature; changes in patient management associated with viral culture results may not have been well documented in medical charts. Moreover, our findings may not be applicable to shell vial methods, which have a more rapid turnaround time compared to traditional culture techniques [18]. Nevertheless, over nearly three years, we observed that routine traditional viral cell culture on specimens negative by multiplex PCR had very low yield and minimal clinical impact in the pediatric population. Our findings can aid microbiology labs to optimize the utilization of respiratory virus testing. We have since modified our laboratory practice to restrict cell culture to respiratory specimens from high-risk immunocompromised children or upon special request.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

J. P. has received investigator-initiated research funds from Becton, Dickenson & Co., served on the scientific advisory board of RPS Diagnostics, and has received speaker’s honoraria from Cepheid. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approved by the McGill University Health Centre pediatric research ethics board (study 15-380-MUHC).

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Patricia Fontela for constructive feedback and discussions.

References

- 1.Yorita K.L. Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):244–252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wishaupt J.O., Versteegh F.G., Hartwig N.G. PCR testing for paediatric acute respiratory tract infections. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2015;16(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leland D.S., Ginocchio C.C. Role of cell culture for virus detection in the age of technology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007;20(1):49–78. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogilvie M. Molecular techniques should not now replace cell culture in diagnostic virology laboratories. Rev. Med. Virol. 2001;11(6):351–354. doi: 10.1002/rmv.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Arroyo L. Benefits and drawbacks of molecular techniques for diagnosis of viral respiratory infections. Experience with two multiplex PCR assays. J. Med. Virol. 2016;88(1):45–50. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkinson D. Delayed RSV diagnosis in a stem cell transplant population due to mutations that result in negative polymerase chain reaction. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013;75(4):426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semret M. A real-time RT-PCR assay for detection of influenza H1N1 (swine-type) and other respiratory viruses. 26th International Congress of Chemotherapy and Infection; June 18–21, 2009: Toronto,ON; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semret M. Multiplex respiratory virus testing for antimicrobial stewardship: a prospective assessment of antimicrobial utilization and clinical outcomes among hospitalized adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix288. https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/3871175/Multiplex-Respiratory-Virus-Testing-for?searchresult=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanzkowsky P., Lipton J.M., Fish J.D., editors. Elsevier/AP; Amsterdam: 2016. Appendix 1 - Hematological Reference Values, in Lanzkowsky's manual of pediatric hematology and oncology; pp. 709–728. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brugnara C. Appendices Reference Value in Infancy and Childhood in Nathan and Oski's Hematology and Oncology of Infancy and Childhood. In: Orkin S.H., editor. 2015. pp. 2484–2535. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellau-Pujol S. Development of three multiplex RT-PCR assays for the detection of 12 respiratory RNA viruses. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126(1–2):53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shetty A.K. Comparison of conventional viral cultures with direct fluorescent antibody stains for diagnosis of community-acquired respiratory virus infections in hospitalized children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2003;22(9):789–794. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000083823.43526.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumino K.C. Detection of respiratory viruses and the associated chemokine responses in serious acute respiratory illness. Thorax. 2010;65(7):639–644. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.132480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landry M., Leland D. Primary isolation of viruses. In: Loeffelholz M.J., editor. Clinical Virology Manual. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2016. pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ison M.G., Rosenberg E.S. RNA respiratory viruses. In: Hayden R.T., editor. Diagnostic Microbiology of the Immunocompromised Host. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2016. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodinka R.L. Point: is the era of viral culture over in the clinical microbiology laboratory? J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51(1):2–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02593-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klungthong C. The impact of primer and probe-template mismatches on the sensitivity of pandemic influenza A/H1N1/2009 virus detection by real-time RT-PCR. J. Clin. Virol. 2010;48(2):91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinberg A. Evaluation of R-Mix shell vials for the diagnosis of viral respiratory tract infections. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;30(1):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]