Highlights

-

•

Rapid isothermal NAT for influenza reveals improved sensitivity and specificity compared to direct antigen testing.

-

•

Simple sample processing and short turn-around time render isothermal NAT suitable for sequential near-patient testing.

-

•

The turn-around time advantage is lost by the single-test format precluding sample cohorting and testing of larger series.

Keywords: Influenza virus, Community-acquired respiratory virus, Isothermal PCR, Turn-around time (TAT), Antigen detection, Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT)

Abstract

Background

Rapid diagnosis of influenza is important for controlling outbreaks and starting antiviral therapy. Direct antigen detection (DAD) is rapid, but lacks sensitivity, whereas nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) is more sensitive, but also more time-consuming.

Objectives

To evaluate the performance of a rapid isothermal NAT and two DADs.

Study design

During February–May 2014, we tested 211 consecutive patients with influenza-like illness using a commercial isothermal NAT (Alere™ Influenza A&B) as well as the DAD Sofia® Influenza A + B and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B for detection of influenza-A and -B virus. RespiFinder-22® a commercial multiplex NAT served as reference test. Serial 10-fold dilutions of influenza-A and -B cell culture supernatants were examined. Another 225 patient samples were tested during December 2014–February 2015.

Results

Compared to RespiFinder-22®, the isothermal NAT Alere™ Influenza A&B, and the DAD Sofia® Influenza A + B and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B had sensitivities of 77.8%, 59.3% and 29.6%, and specificities of 99.5%, 98.9% and 100%, respectively, for the first 211 patient samples. Alere™ Influenza A&B showed 85.7% sensitivity and 100% specificity in the second cohort. Isothermal NAT was 10-100-fold more sensitive compared to DAD for influenza virus culture supernatants with a lower limit of detection of 5000–50,000 copies/mL. The average turn-around time (TAT) of isothermal NAT and DADs was 15 min, but increased to 110 min for Alere™ Influenza A&B, 30 min for BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B, and 45 min for Sofia® Influenza A + B, when analyzing batches of 6 samples.

Conclusion

Simple sample processing and a TAT of 15 min render isothermal NAT Alere™ Influenza A&B suitable for sequential near-patient testing, but the TAT advantage is lost when testing of larger series.

1. Background

Rapid and sensitive diagnostic tests for influenza virus permit timely treatment decisions and infection control measures in emergency rooms, hospital wards, and nursing homes [1], [2], [3]. The current methods used for the laboratory diagnosis of influenza include virus isolation by cell culture, direct antigen detection (DAD), and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT). Virus isolation by cell culture permits identification of infectious virus with fairly high sensitivity, but is time- and resource-consuming and largely limited to specialized laboratories. DAD has been widely used because of its short turn-around time (TAT), but is limited by its lower sensitivity, especially in adult patients and those presenting several days after symptom onset [4], [5]. NAT is characterized by high sensitivity and specificity, semi-quantification in real-time formats, and its amenability to automation and multiplexing [6]. However, NAT requires a molecular diagnostic laboratory with skilled personnel, appropriate instrumentation, but rarely delivers results with TAT of <6 h.

2. Objective

To evaluate the performance of the isothermal PCR for influenza (Alere™ Influenza A&B) and two DADs (Sofia®Influenza A + B and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B) versus a commercial multiplex NAT (RespiFinder-22®).

3. Study design

Between February 2014 and May 2014, we tested a first cohort of 211 consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs from patients with influenza-like illness by the isothermal NAT Alere™ Influenza A&B (Alere, Wädenswil, Switzerland) and the DADs Sofia® Influenza A + B (Quidel Corp., San Diego, CA; USA) and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B (Alere, Wädenswil, Switzerland). RespiFinder-22® served as the primary reference test. A second prospective series of 225 samples submitted between December 2014 and February 2015 (cohort 2) compared only Alere™ Influenza A&B with RespiFinder-22®. Discordant results were retested using the local in-house QNAT [7].

The 436 nasopharyngeal swabs were taken from 178 females and 258 males (median age, 4 years; interquartile range [IQR] 0–49 years) for influenza diagnostics between February 2014 and May 2014 and December 2014 and February 2015. Of the 275 pediatric patients, 140 (50.9%) were less than 1 year old. Of the 161 adult patients, 69 (42.9%) were older than 60 years. 423 samples (97.0%) were analyzed prospectively from fresh samples, 211/436 were examined in parallel with all 4 methods (DADs, isothermal NAT and multiplex NAT). For 13 (3.0%), testing was done retrospectively from frozen samples.

Alere™ Influenza A&B, BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B, and Sofia® Influenza A + B testing was performed as described by the manufacturer. The average assay time was 15 min for Alere™ Influenza A&B and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B, and 20 min for Sofia® Influenza A + B. RespiFinder-22® (PathoFinder, Maastricht, The Netherlands) had a TAT of 16 h [6], [8]. Discordant samples were resolved by in-house QNAT for influenza [7] with a TAT of 6 h. Total nucleic acids were extracted from 200 ul of the respiratory sample using the Corbett CAS-1200 system (Qiagen Hilden, Germany).

4. Results

In total, 57/436 samples (13.1%) were positive for influenza-A (25 in the first and 32 in the second cohort) and 5/436 samples (1.1%) for influenza-B (2 in the first, and 3 in the second cohort) by RespiFinder-22®. The Alere™ Influenza A&B identified 47/436 (10.8%) influenza-A, and 4/436 (0.9%) influenza-B. Of the 57 influenza-A positive samples, 16 could be classified as subtype H1N1 (28.1%), 41 as subtype H3N2 (71.9%). The BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B detected influenza-A in 8/211 (3.8%) specimens and no influenza-B, the Sofia® Influenza A + B assay identified influenza-A in 14/211 (6.6%), influenza-B in 2/211 (0.9%) samples. Discordant results of 12 samples were resolved by influenza-specific QNAT. The performance of all three rapid tests compared to the reference method for influenza-A and -B combined is shown in Table 1 . Using multiplex NAT as reference, Alere™ Influenza A&B, Sofia® Influenza A + B, and BinaxNOW® InfluenzaA&B had sensitivities of 82.3%, 59.3% and 29.6%, and specificities of 99.7%, 98.9% and 100%, respectively.

Table 1.

Performance of Alere™, Sofia® and BinaxNOW® influenza A and B assays.

| Alere™ Inf A&B | TP | FP | TN | FN | Total | % Sensitivity (95% CI) | % Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period 1 | 21 | 1 | 183 | 6 | 211 | 77.8 (57.7− 91.3) | 99.5 (97.0−99.9) | 95.5 (77.1 −99.2) | 96.8 (93.2 −98.8) | 0.84 |

| Study period 2 | 30 | 0 | 190 | 5 | 225 | 85.7 (69.7−95.1) | 100 (98.1−100) | 100 (88.3−100) | 97.4 (94.3− 99.2) | 0.91 |

| Study period 1 + 2 | 51 | 1 | 373 | 11 | 436 | 82.3 (70.5−90.8) | 99.7 (98.5− 100) | 98.1 (89.7 - 99.7) | 97.1 (94.3−98.6) | 0.88 |

| Sofia® Inf A + B | ||||||||||

| Study period 1 | 16 | 2 | 182 | 11 | 211 | 59.3 (38.8−77.6) | 98.9 (96.1−99.8) | 88.9 (65.2 −98.3) | 94.3 (90.0−97.1) | 0.68 |

| BinaxNOW® Inf A&B | ||||||||||

| Study period 1 | 8 | 0 | 183 | 19 | 210 | 29.6 (13.8−50.2) | 100 (98.0−100) | 100 (62.9−100) | 90.6 (85.7−94.2) | 0.42 |

TP: True positives; FP: False positives; TN: True negatives; FN: False negatives; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; CI: Confidence interval; : Interobserver agreement; Study period 1: February 2014–May 2014, Study period 2: December 2014–February 2015; data for influenza-A and -B were taken into account.

Specificity of the test could be confirmed with influenza-negative samples that had been tested with RespiFinder-22® (n = 373). Multiplex NAT detected 14 other pathogens in these samples including rhinovirus/enterovirus, coronavirus OC43, NL63, 229E and HKU1, human bocavirus, RSV A and RSV B, adenovirus, parainfluenza-3, parainfluenza-4, human metapneumovirus and the bacteria Bordetella pertussis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. None of the 11 false-negative samples were positive for another pathogen. Overall, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and κ values (interobserver agreement) for influenza-A and -B were slightly higher for specimens from pediatric patients (89.5%).

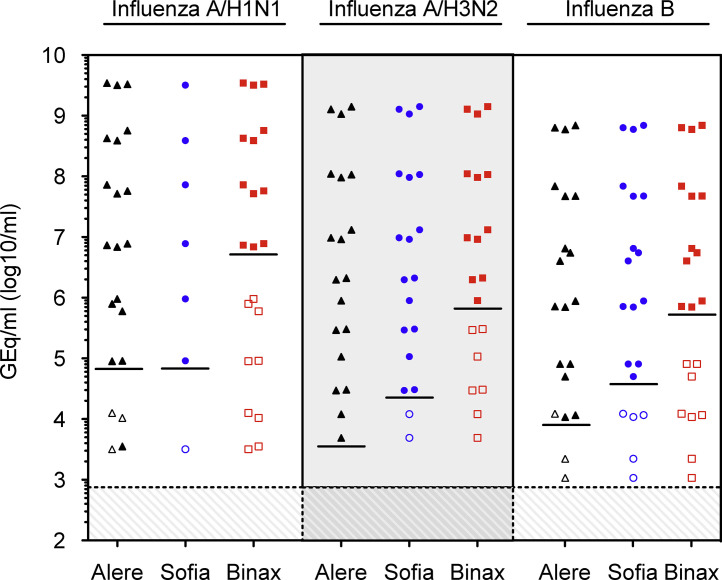

The limit of detection for the tests was evaluated using serial dilutions of fresh cell culture supernatant of influenza-A H3N2 and H1N1 and influenza-B grown on LLC-MK2 cells (Fig. 1 ). For influenza-A, the detection limit of the Alere™ Influenza A&B according to QNAT was approximately 5,000 GEq/mL (H3N2), 50,000 GEq/mL (H1N1), and 10,000 GEq/mL for Influenza-B. Overall, the sensitivity of both DADs (Sofia® Influenza A + B and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B) were about 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than for Alere™ Influenza A&B.

Fig. 1.

Comparing the detection of influenza virus in cell culture supernatant by different near-patients tests. The indicated influenza viruses were grown in cell culture on LLC-MK2 cells and three independent 10-fold dilutions of each supernatant were prepared. The dilutions were directly tested using the Alere™ Influenza A&B (Alere, triangles), Sofia® Influenza A + B (Sofia, circles), and BinaxNOW® Influenza A&B (Binax, squares). In parallel, the dilutions were extracted and quantified by QNAT as described in study design [7]. Solid symbols, positive testing; open symbols, negative testing; lines, lower limit of detection of indicated rapid test; hatched area, limit of detection of the influenza QNAT.

5. Discussion

In our prospective study, the overall sensitivity and specificity of the Alere™ Influenza A&B assay was 82.3% and 99.7% for influenza.

Several factors may have played a role:

-

1.

A large number of the samples (n = 211) from the first cohort were obtained towards the end of the influenza season between February and May 2014, which decreases the positivity rate and pretest probability.

-

2.

13/436 samples were analyzed retrospectively from frozen samples, but the manufacturer recommends using fresh samples. By excluding these 13 samples from analysis, the sensitivity increased to 86.5% and the specificity to 100%. Possibly, tests using high-grade extraction-amplification procedures are less affected by testing frozen samples, even with lower amounts of influenza virus, than Alere™ Influenza A&B. Of those 13 samples 5 resulted in discordant results with the Alere™ Influenza A&B assay, with viral QNAT loads between 30 and 18,000 GEq/mL.

-

3.

Influenza-A and -B from cell culture estimated the limit of detection of around 5,000 to 50,000 GEq/mL for Alere™ Influenza A&B. Therefore, patients with lower viral loads might not be identified.

-

4.

The overall low number of influenza-B in both test series limits an independent conclusion about the assay performance. Other studies report a sensitivity of Alere™ Influenza A&B of 73%–99% for influenza-A, 97%–100% for influenza-B; and specificity of 95%–100% for influenza-A, and 100% for influenza-B [9], [10], [11].

In cohort-1, Alere™ Influenza A&B yielded 1 false-positive result among 211 samples, and no false-positives among 225 samples of cohort-2. The rate corresponds to 0.23% or 1 among 436 symptomatic patients, which would be unjustifiably treated or isolated. Conversely, antiviral treatment would be withheld in 373 patients tested negative. While the data suggest that testing of patients improves timely delivery of antivirals, 15 per 100 infected would not receive this treatment. The clinical impact may differ depending on the clinical scenario: hospitalized patients are likely to be confirmed during the course of their disease, whereas outpatients are less likely to be re-tested unless symptoms persist.

The current study indicates that isothermal NAT as provided by the Alere™ Influenza A&B is significantly faster than conventional QNAT (15 min versus 6–8 h) or multiplex NAT (16 h) and comparable to DAD. As the sample preparation is equally simple, the Alere™ Influenza A&B could potentially be performed outside of the molecular diagnostic laboratory setting e.g., in a physician’s office or in the emergency room. This could save transport time to the laboratory. However, care needs to be taken that the individuals operating the system are properly trained and certified. In the single sample testing, however, running larger numbers of more than 6 patient samples becomes challenging, and the TAT advantage of isothermal PCR is lost.

Taken together, the Alere™ Influenza A&B can reduce the TAT compared to multiplex NAT or QNAT. The sensitivities and specificities were comparable to conventional NAT reference tests and superior to the two DAD assays. The Alere™ Influenza A&B may be attractive for first-line rapid testing of individual patients presenting to health care, followed by QNAT or multiplex NAT, when information on relative amounts or the presence of other viruses is needed.

Funding

None.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues of the Division Infection Diagnostics and the technicians of the molecular diagnostics and virus isolation laboratories for support and assistance.

References

- 1.D’Heilly S.J., Janoff E.N., Nichol P., Nichol K.L. Rapid diagnosis of influenza infection in older adults: influence on clinical care in a routine clinical setting. J. Clin. Virol. 2008;42:124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falsey A.R., Murata Y., Walsh E.E. Impact of rapid diagnosis on management of adults hospitalized with influenza. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:354–360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.4.ioi60207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch H.H., Martino R., Ward K.N., Boeckh M., Einsele H., Ljungman P. Fourth European conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL-4): guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of human respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, metapneumo virus, rhinovirus, and coronavirus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:258–266. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams L.O., Kupka N.J., Schmaltz S.P., Barrett S., Uyeki T.M., Jernigan D.B. Rapid influenza diagnostic test use and antiviral prescriptions in outpatient settings pre- and post-2009H1N1 pandemic. J. Clin. Virol. 2014;60:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd M. Influenza viruses: update on epidemiology, clinical features, treatment and vaccination. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2014;20:242–246. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumoulin A., Widmer A.F., Hirsch H.H. Comprehensive diagnostics for respiratory virus infections after transplantation or after potential exposure to swine flu A/H1N1: what else is out there? Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2009;11:287–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna N., Steffen I., Studt J.D., Schreiber A., Lehmann T., Weisser M. Outcome of influenza infections in outpatients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2009;11:100–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidler J.A., Haberthur C., Dumoulin A., Hirsch H.H., Heininger U. A retrospective analysis of nosocomial viral gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2012;31:1233–1238. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826781d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell J., Bonner A., Cohen D.M., Birkhahn R., Yogev R., Triner W. Multicenter clinical evaluation of the novel Alere i Influenza A&B isothermal nucleic acid amplification test. J. Clin. Virol. 2014;61:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell J.J., Selvarangan R. Evaluation of the alere i influenza a&b nucleic Acid amplification test by use of respiratory specimens collected in viral transport medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:3992–3995. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01639-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nie S., Roth R.B., Stiles J., Mikhlina A., Lu X., Tang Y.W. Evaluation of Alere I Influenza A&B for rapid detection of Influenza viruses A and B. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:3339–3344. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01132-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]