Summary

Involuntary migration is a crucially important global challenge from an economic, social, and public health perspective. The number of displaced people reached an unprecedented level in 2015, at a total of 60 million worldwide, with more than 1 million crossing into Europe in the past year alone. Migrants and refugees are often perceived to carry a higher load of infectious diseases, despite no systematic association. We propose three important contributions that the global health community can make to help address infectious disease risks and global health inequalities worldwide, with a particular focus on the refugee crisis in Europe. First, policy decisions should be based on a sound evidence base regarding health risks and burdens to health systems, rather than prejudice or unfounded fears. Second, for incoming refugees, we must focus on building inclusive, cost-effective health services to promote collective health security. Finally, alongside protracted conflicts, widening of health and socioeconomic inequalities between high-income and lower-income countries should be acknowledged as major drivers for the global refugee crisis, and fully considered in planning long-term solutions.

Introduction

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) stated that the number of displaced people globally rose by 16% between 2014 and 2015—the greatest ever increase in 1 year—reaching an all-time high of 60 million worldwide.1 This figure includes about 38 million internally displaced people, 20 million refugees, and 2 million asylum seekers. Between January, 2015, and May, 2016, more than 1·2 million people have crossed the Mediterranean Sea to Europe, including economic migrants hoping for a better life and refugees fleeing conflicts, political upheaval, ethnic discrimination, and religious persecution. The continuing swell of refugees worldwide is creating an ever-increasing economic and social burden on host countries and presents new public health challenges, alongside the deeper humanitarian and social issues. With such mass involuntary migration—and the associated overcrowding, poor sanitation, and restricted access to clean water—often comes a substantial increase in risk of infectious disease outbreaks, depending on the context. For example, after an official declaration of cholera outbreaks in Iraq in September, 2015, and with the continued degradation of health services and surveillance infrastructure in neighbouring Syria, the risk of disease contagion and large-scale outbreaks occurring in the wider region is increasing.2

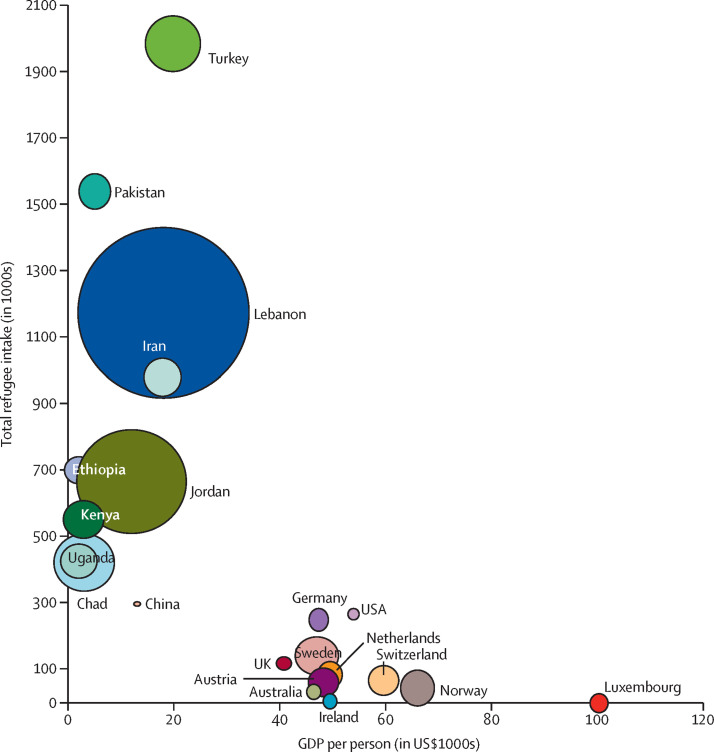

The overwhelming burden to host large populations of displaced people, and to manage potential infectious disease risks associated with their influx has, for decades, fallen on low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). Between 2009 and 2013, for example, 86% of all refugees were hosted in LMICs, many of which already face a substantial infectious disease burden.1 The number of refugees hosted by LMICs is more than five times the number hosted by the ten richest countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; figure ).3, 4 Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon, and Iran together host a staggering 5·2 million refugees.5 Political, infrastructural, and financial constraints in LMICs have often been obstacles to providing access to health services and infectious disease screening programmes for the refugee populations. Constraints in the host countries have often had to be mitigated through support from UNHCR and other international organisations.

Figure.

Refugee intake in low-income countries versus Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, as of June, 2015

The size of each bubble is proportional to refugee intake per 1000 people of the host country population. Data are from the UN High Commissioner For Refugees3 and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,4 2015. GDP=gross domestic product.

With refugees now being forced to migrate to high-income countries—most notably to Europe—the issue has rapidly risen up the global political agenda. The World Economic Forum now, unsurprisingly, ranks involuntary migration as one of the greatest risks to the world economy.6 However, in some of these high-income countries, migrants and refugees have been coalesced into one emotive security issue, with the risk that policies ignore other softer, but equally important, issues such as collective health security, which can only be guaranteed by social integration and equitable access to health care.

After terrorist attacks in the past year in Turkey, Lebanon, France, and Belgium and media reports of sexual and physical assaults in Europe, there is a danger that exaggerated associations will be drawn between refugees, terrorism, and criminality. As a result, policies and interventions in high-income countries taking in refugees will be increasingly framed mainly in relation to risks to national security rather than equity and global health security. We propose three broad contributions that could be made by the global health community to help assess, better inform, and reduce potential infectious disease risks associated with incoming refugees, and improve social integration in relation to the refugee crisis in Europe.

First, we propose to ensure that evidence is obtained about the true infectious disease risks from refugees and the burden they cause to health systems to prevent prejudicial concerns and unfounded stigmatisation.

Many refugees come from areas with high poverty and weak health systems, and several European countries are concerned about refugees bringing previously controlled infections within their borders. The arduous journey that many refugees have endured might increase their risk of infectious diseases—particularly of measles and food and water-borne diseases to which they are at an increased risk if immunisation programmes were interrupted in their countries of origin.7 However, despite the commonly held view of an association between migration and spread of infectious diseases, no systematic association has been shown with many of the infectious diseases of concern. For example, enteric fever is already reported in the European region with most cases occurring in returning travellers rather than refugees or migrants. Additionally, the risk of other infectious diseases, including viral haemorrhagic fevers or Middle East respiratory syndrome, is low with most cases occurring in health-care workers or travellers rather than refugees.7 The threat of infectious disease outbreaks from population movements to Europe might thus be substantially less than perceived.

Any misinformation reported in the press and on social media exaggerating the health and infectious disease risks associated with incoming refugees must be firmly countered with epidemiological data and a pragmatic approach to disease control. The evidence must be clearly provided and understood by politicians and the general public. To generate a strong evidence base, a coordinated approach to health needs assessments and surveillance should be developed, leveraging institutional networks such as the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and its links to reference laboratories and individual national public health agencies. Estimation of the infectious disease risk to Europe from cholera, for example, should take into account the well developed public water and sanitation systems, excellent health infrastructure, and well integrated and responsive disease surveillance networks, all of which substantially reduce the chances of large outbreaks of cholera. Accurate communication of infectious disease risk assessments to the general public and policy makers is thus key to rationalise the broader debate for this issue.

For example, concerns about transmission of polio from Syrian refugees into Europe after the 2013–14 outbreak of polio were unfounded. Although cases traceable to Syria were identified in Iraq,8 no cases were identified in asymptomatic toddlers screened in Germany.9 Yet, both the medical10 and lay press coverage had extensively discussed the so-called polio threat in view of low vaccination rates in the UK and Germany. What these reports did not consider was the ability of the global system to respond appropriately. The global response in that instance was measured, and risk communication on the whole was effective, with WHO's Emergency Committee's declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. The declaration brought WHO's Global Polio Eradication Initiative together with different organisations to complete several rounds of vaccinations in affected areas, and was effective at controlling the outbreak and minimising risk of spread.

Similarly, for tuberculosis, another infectious disease of concern, the potential for spread and disease progression will likely be reduced in the European population—compared with low-resource settings—owing to improved nutritional status and housing conditions. Most refugees entering Europe come from Syria, which had a tuberculosis prevalence of 23 people per 100 000 population in 2011, and 19 people per 100 000 population in 2014.11, 12 Tuberculosis prevalence in Syria is thus lower than the average in the European region of 39 people per 100 000 population,13 and substantially below many European countries (table ).3, 4 Furthermore, tuberculosis transmission from refugees to local populations does not occur often because of sparse contact. Early diagnosis and effective care of this disease will further minimise risk. Studies14 completed in countries with low tuberculosis burden, such as Denmark, have indicated that transmission from refugees to local populations is low, and that refugees are more likely to be infected with tuberculosis by local populations than vice versa.

Table.

Tuberculosis prevalence in Syria and selected European countries in 2014

| Tuberculosis prevalence per 100 000 population | |

|---|---|

| Syria | 19 |

| Bulgaria | 33 |

| Croatia | 16 |

| France | 12 |

| Germany | 8 |

| Greece | 6 |

| Latvia | 57 |

| Lithuania | 83 |

| Italy | 7 |

| Netherlands | 7 |

| Norway | 10 |

| Poland | 26 |

| Portugal | 29 |

| Romania | 99 |

| Spain | 15 |

| UK | 15 |

Data are from WHO.12

Thus, the evidence indicates that infectious disease risks to Europe are small. This risk level needs to be effectively communicated to both host communities and the incoming refugees.

Second, we strongly recommend that access to health care for all refugees and migrants is ensured through regular health checks for both communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs); hospital and high-quality health-care prevention and curative services are provided without discrimination on the basis of sex, age, religion, nationality, or ethnic origin; are cost-effective; and are culturally appropriate approaches, maintaining people's human rights and dignity.

WHO emphasises that results of infection screening should not be a reason to deport a refugee.7 Refugees have suffered long and arduous stressful journeys, enduring cramped and unhygienic environments, which take a toll on their mental and physical health and existing NCDs. Many European countries, including the UK, request medical screening in the host country and then complete further screening of refugees on arrival, including targeted tuberculosis screening for those in the UK.15 The USA has an established programme of mandatory screening of refugees both before departure and after arrival to establish immunisation status and the presence of parastic infections or other communicable diseases.16, 17 A review18 of the screening stratetgy after arrival of Iraqi refugees in the USA completed between 2008 and 2009 identified a 14·1% prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection. Additionally, the review18 noted that despite the traditional focus of refugee medical screening, morbidity due to NCDs was of higher prevelance. This observation is mirrored in other refugee populations from the Middle East, particularly in those of Syrian origin, in whom NCDs are more prevalent than infectious diseases.

WHO does not recommend compulsory mass screening of refugee or migrant populations, although it does recommend health checks for both infectious diseases and NCDs and access to health services while maintaining the dignity of refugees and migrants.19 No evidence shows that mass compulsory checks have a benefit or are cost-effective. Furthermore, these checks have a possible risk of causing anxiety to individuals and deterring refugees and migrants from seeking health care if needed.7 Screening programmes should be rationalised and prioritised for incoming refugees from settings with a large disease burden, for conditions which can be shown to have effective treatments,20 rather than attempt to cover all arrivals particularly where local services are overwhelmed by volume. After arrival, screening and assessment of immunisation status might be particularly important to reduce the risk of outbreaks, especially if refugees originate from areas where vaccination programmes were interrupted.

Promotion of refugee access to appropriate and culturally acceptable health services, and encouragement of their integration is, we believe, fundamental to ensure Europe's collective health security. This aim can only be achieved if incoming refugees feel welcome and not the subject of stigmatisation or persecution.7 Experience from around the world shows that many refugee groups—eg, Myanmar's Rohingya minority—have long been deprived of essential health care in their home countries, and arrive in host countries in extremely poor health. These poor baseline health conditions might be exacerbated by provision of inadequate health services at refugee reception or processing centres, which can thus become a risk to the collective health of host populations. For example, conditions in Australia's Nauru and Manus Island detention centres for offshore processing have resulted in outbreaks of infectious diseases.21 By contrast, the strong system of vaccination surveillance in Germany identified low measles immunisation in incoming refugees to Lower Saxony; measures are being taken to vaccinate arriving groups, illustrating how evidence can be used to reduce health inequalities in refugees and host communities. The European Vaccine Action Plan 2015–202022 details the importance of equitable access to vaccination and to encourage access for refugees and migrants with culturally appropriate services.7

High-income countries have all the experience, knowledge, and resources to find cost-effective solutions to health challenges that might arise from incoming refugees, as well as the institutional strength and innovative capacity to integrate and harness the potential socioeconomic benefits of these incoming groups. Innovative solutions to strengthen the control of infectious diseases in refugee populations could include mobile diagnostic and surveillance units similar to the Find and Treat service for tuberculosis for homeless and disadvantaged people in London.23 These solutions could also include an integrated support function for psychosocial care and new public–private partnerships for health surveillance, delivery of messages about health promotion and phone-based incentives, and signposting of essential health services. Lessons could be learnt from the large US refugee resettlement programme17, 24 and their electronic disease notification system used since 2006, which has improved the timeliness and accuracy of infectious disease notifications. However, further studies should include economic analyses that account for long-term outcomes for conditions, such as latent tubterculosis infections, detected in incoming refugees.

Sweden, where more than 100 000 refugees were taken in during 2015, is trialing creative approaches to integrate refugee communities, improve health literacy, and ensure adequate access to health services. Sweden has introduced many fast-track schemes to integrate refugees (particularly from Syria), who are already medically trained, into the labour market, thus addressing many difficulties associated with staff shortages, language barriers, and cultural sensitivity.25

However, for interventions to be effective, improved coordination and cooperation is needed by European countries. Additionally, there is a need for a more integrated and well managed role for humanitarian non-governmental organisations to provide services for refugees in the absence of adequate provision by government and local authority agencies. In 2015, an important step was taken in this direction with the publication of a joint statement—by European countries, the European Commission, and WHO—addressing the health needs of incoming refugees to Europe26 and the development of a patient health record that will be piloted at borders to evaluate refugees' medical needs and to reconstruct their medical history.27 A joint technical statement by UNHCR, WHO, and UNICEF on vaccination for refugees entering Europe provides further support to harmonise and develop consistent standards in the continent. These efforts are important and build on the continuing work of WHO's Europe Public Health Aspects of Migration in Europe project,28 which has developed both evidence-based guidance and a series of tools to assist countries to assess and address the health needs of migrant and refugee populations. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of these initiatives continues to be limited by the insufficient financial and political commitment to improve cross-border coordination for the health needs of refugees.

Finally, political leaders need to understand and acknowledge that alongside conflict and violence, widening socioeconomic and health inequalities (ie, the broader determinants of health) between and in countries is one principal driver of refugee migration. Development initiatives must therefore focus on improvements to health systems, transparency, governance, and political stability in the countries from which refugees derive. The 2015 EU agreement29 to provide US$1·9 billion to address the drivers of outward migration from Africa implied some recognition of these drivers of migration. Hopefully, some of that fund could be used to support more equitable structuring of economic and commercial agreements between LMICs and high-income countries, and a more equal sharing of profits. Turkey has now been promised an additional $3·2 billion to stem the outward flow of refugees to Europe, but these funds are being directed more at border security and have not been sufficiently aimed at addressing this underlying driver of health and socioeconomic inequalities experienced by refugees in unstable environments.30

Leaders in European countries and other destination regions for refugees need to develop an improved awareness and understanding of this driver and resist measures that compound inequalities both abroad and at home. The 2015 UK Department of Health's consultation on extending charges to visitors, refugees, and migrants and accessing primary and secondary care services in the UK, done with little public or professional engagement,31 highlights some of the prevailing attitudes developing in Europe that threaten collective health security. This consultation seems to show a continuing erosion of the founding principles of the UK National Health Service, framed about reducing inequalities through universal health coverage, free at the point of access. If implemented as planned, the recommended measures31 will likely lead to late diagnosis of medical conditions, including of infectious diseases (although these are exempt from further charges once a diagnosis has been made), and worse health outcomes for refugees and migrants because the poorest groups delay accessing services to restrict outgoing costs.

In summary, one fundamental, long-term possible solution to the refugee crisis, and the associated potential infectious disease challenges for countries receiving refugees, is for more economically fortunate countries to increase efforts to reduce the health and socioeconomic inequalities driving populations to become refugees. However, to ensure collective health security and prevent disease outbreaks in countries receiving refugee populations, a short-term solution must be to better engage with those who have already arrived and with those who will continue to arrive in the foreseeable future. Measures to address health inequalities, through improved disease risk assessment, better health-care access, and a more culturally sensitive health service support both refugee integration and help to reduce threats from infectious diseases. Such measures must be viewed as a key component in any broader security strategy.

The Aliens Order of 1920 barred entry of immigrants with a range of medical conditions to the UK.32 This order was reversed during the World Refugee Year (1959–60), and allowed entry of refugees who had tuberculosis and other chronic illnesses.33 In view of the overall number of refugees worldwide consistently increasing in recent years, we now have an even greater collective responsibility to help address the current crisis. The refugee situation is not, however, all doom and gloom. Many have readily engaged with and are actively contributing to improve the lives of displaced populations.34, 35 These many individuals and host communities reaffirm a shared humanity and demonstrate a commitment to a more equal world.

Contributors

OD, AZ, and MSK conceived the idea and developed the first and final drafts. AOK led the development of the figure. All other authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.UNHCR UNHCR global trends, forced displacement in 2014. 2014. http://unhcr.org/556725e69.html#_ga=1.225701913.2095888809.1417795315 (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 2.Bagcchi S. Cholera in Iraq strains the fragile state. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:24–25. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.OECD OECD data, domestic product, gross domestic product (GDP) 2015. https://data.oecd.org/gdp/gross-domestic-product-gdp.htm (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 4.UNHCR 2015 UNHCR country operations profile. 2015. http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e486566&submit=GO (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 5.Malavota F, International Organisation for Migration . Global migration trends: an overview. International Organisation for Migration; London: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Economic Forum . The global risks report 2016. 11th edn. World Economic Forum; Geneva: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Migration and health: key issues. 2016. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/migration-and-health/migrant-health-in-the-european-region/migration-and-health-key-issues#292117 (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 8.Gulland A. World has been slow to act on polio outbreak in Syria, charity warns. BMJ. 2014;348:g1947. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert A, Böttcher S, Eis-Hübinger A. Two cases of vaccine-derived poliovirus infection in an oncology ward. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1296–1298. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1508104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler D. Polio risk looms over Europe; cases in Syria highlight vulnerability of nearby countries to the viral disease. Nature. 2013;503:7443. doi: 10.1038/502601a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cookson ST, Abaza H, Clarke KR. “Impact of and response to increased tuberculosis prevalence among Syrian refugees compared with Jordanian tuberculosis prevalence: case study of a tuberculosis public health strategy”. Confl Health. 2015;9:18. doi: 10.1186/s13031-015-0044-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Tuberculosis country profiles. 2016. http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/ (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 13.Mockenhaupt FP, Barbre KA, Jensenius M. Profile of illness in Syrian refugees: a GeoSentinel analysis, 2013 to 2015. Euro Surveill. 2016;21:2. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.10.30160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamper-Jørgensen Z, Bengaard Andersen A, Kok-Jensen A. Migrant tuberculosis: the extent of transmission in a low burden country. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.IOM Migration health; healthy migrants in healthy communities; UK TB detection programme. 2013. https://health.iom.int/uk-tb-detection-programme (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 16.UK Home Office Syrian vulnerable person resettlement (VPR) programme: guidance for local authorities and partners. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/472020/Syrian_Resettlement_Fact_Sheet_gov_uk.pdf (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 17.US CDC Refugee health guidelines; guidelines for pre-departure and post-arrival medical screening and treatment of US-bound refugees. 2012; updated 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/refugee-guidelines.html (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 18.US CDC Health of resettled Iraqi refugees—San Diego County, California, October 2007–September 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1614–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Regional Office for Europe Migration and health: key issues. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/migration-and-health/migrant-health-in-the-european-region/migration-and-health-key-issues (accessed June 14, 2015).

- 20.Sanneh AF, Al-Shareef AM. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of screening immigrants schemes for tuberculosis (TB) on arrival from high TB endemic countries to low TB prevalent countries. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14:663–671. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i3.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Procter N, Sundram S, Singleton G, Paxton G, Block A. Physical and mental health subcommittee of the joint advisory committee for Nauru regional processing arrangements: Nauru site visit report. The Guardian (London), May 29, 2014.

- 22.WHO . European Vaccine Action Plan 2015–2020. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.University College London Hospitals University College London Hospitals find and treat service. 2016. https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/OURSERVICES/SERVICEA-Z/HTD/Pages/MXU.aspx (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 24.Lee D, Philen R, Wang Z. Disease surveillance among newly arriving refugees and immigrants—electronic disease notification system, United States, 2009. Surveillance summaries. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swedish Network for International Health Refugee health—the Swedish experience. 2015. http://www.snih.org/refugee-health-the-swedish-experience/ (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 26.WHO Regional Office for Europe Refugee and migrant health meeting, background. 2015. http://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/events/events/2015/11/high-level-meeting-on-refugee-and-migrant-health/background (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 27.European Commission Refugees: commissioner Andriukaitis presents the personal health record in Greece. 2015. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/health_food-safety/dyna/enews/enews.cfm?al_id=1647 (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 28.WHO Regional Office for Europe Migrant health in the European region. 2016. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/migration-and-health/migrant-health-in-the-european-region (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 29.European Commission A European agenda on migration. 2015 Valletta Summit on migration: a European Union emergency trust fund for Africa. 2015. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/background-information/docs/2_factsheet_emergency_trust_fund_africa_en.pdf (accessed May 9, 2016).

- 30.Kanter J, Higgins A. EU offers Turkey 3 billion Euros to stem migrant flow. New York Times (New York, NY), Nov 29, 2015: A4.

- 31.UK Department of Health . Overseas visitors and migrants: extending charges for NHS services 2015. UK Department of Health; London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor B. Immigration, statecraft and public health: the 1920 Aliens Order, medical examinations and the limitations of the state in England. Soc Hist Med. 2016:1–22. doi: 10.1093/shm/hkv139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor B. A change of heart? British policies towards tubercular refugees during 1959 World Refugee Year. 20 Century Br Hist. 2015;26:97–121. doi: 10.1093/tcbh/hwu022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bozorgmehr K, Bruchhausen W, Hein W. The global health concept of the German government: strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23445. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amorim C, Douste-Blazy P, Wirayuda H. Oslo ministerial declaration—global health: a pressing foreign policy issue of our time. Lancet. 2007;369:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60498-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]