Abstract

Colonization of the skin by Staphylococcus aureus is associated with exacerbation of atopic dermatitis (AD), but any direct mechanism through which dysbiosis of the skin microbiome may influence the development of AD is unknown. Here, we show that proteases and phenol-soluble modulin α (PSMα) secreted by S. aureus lead to endogenous epidermal proteolysis and skin barrier damage that promoted inflammation in mice. We further show that clinical isolates of different coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) species residing on normal skin produced autoinducing peptides that inhibited the S. aureus agr system, in turn decreasing PSMα expression. These autoinducing peptides from skin microbiome CoNS species potently suppressed PSMα expression in S. aureus isolates from subjects with AD without inhibiting S. aureus growth. Metagenomic analysis of the AD skin microbiome revealed that the increase in the relative abundance of S. aureus in patients with active AD correlated with a lower CoNS autoinducing peptides to S. aureus ratio, thus overcoming the peptides’ capacity to inhibit the S. aureus agr system. Characterization of a S. hominis clinical isolate identified an autoinducing peptide (SYNVCGGYF) as a highly potent inhibitor of S. aureus agr activity, capable of preventing S. aureus–mediated epithelial damage and inflammation on murine skin. Together, these findings show how members of the normal human skin microbiome can contribute to epithelial barrier homeostasis by using quorum sensing to inhibit S. aureus toxin production.

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is among the most common immune disorders and poses a serious risk of comorbidities and a major burden to patient quality of life (1,2). Risk of developing AD is increased in patients with genetic defects in skin barrier function and is also associated with early life environmental exposure to various allergens (3–5). Furthermore, recent studies of the composition of the skin microbial community have suggested that a relative abundance of bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococcal (CoNS) species may predict the development of AD (6, 7). These observations follow several decades of reports that S. aureus often colonizes lesions on the skin of patients with AD (8) and positively correlates with disease severity (9–11). Despite the large body of work to identify genetic, environmental, and microbial risk factors that may cause AD, there is as of yet no validated, cohesive hypothesis to link these observations together into a unifying pathophysiologic mechanism.

AD is characterized by a T helper 2 (TH2)–dominant immune phenotype. Patients with AD have increased amounts of TH2 cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 in the skin (12, 13). These cytokines promote decreased function of the skin barrier by inhibiting expression of filaggrin (14) and suppressing expression of antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidin and β-defensin-2. These defects promote dysbiosis of the skin bacterial community and enhanced colonization by S. aureus (15). Therapy targeting the IL-4 receptor α results in a substantial improvement in disease (16). The strong association between TH2 cytokine activity, barrier function, antimicrobial activity, and disease outcome supports efforts to define a causal link between these essential epidermal functions. However, it has not been shown how dysbiosis can promote or enable skin disease.

Recent evidence has demonstrated that virulence factors produced by S. aureus, such as phenol-soluble modulin α (PSMα) and PSMδ, can promote skin inflammation in mice (17–20). PSMs represent a family, often cytolytic, of peptides secreted by S. aureus and include PSMα1 to PSMα4, PSMβ1 and PSMβ2, PSMδ and the recently observed PSM-mec. In addition to promoting inflammation, S. aureus virulence factors can also cause epidermal barrier disruption, a key element in the pathophysiology of AD, by inducing expression of endogenous proteases from keratinocytes (21). Other studies have shown that the potential for S. aureus to induce inflammation can be linked to genetic disorders in barrier assembly including mutations in the filaggrin gene and the penetration of bacteria into deeper layers of the skin (22, 23). Together, we hypothesized that skin inflammation is promoted by penetration of S. aureus below the epidermis and that this may be caused by the action of S. aureus to increase protease activity in keratinocytes, thus disrupting the skin barrier.

This investigation sought to identify the molecular mechanism responsible for the deleterious effects of S. aureus on the epidermal barrier and further define how dysbiosis at the skin surface permits this microbe to promote inflammation. Our study uncovers a previously unappreciated interaction between microbial communities on the skin that reinforces the need for microbial diversity in AD. These data show that interspecies quorum sensing between bacteria on human skin is an important defense mechanism for suppressing the capacity of S. aureus to damage the epidermis.

RESULTS

PSMα and proteases produced by S. aureus induce epidermal barrier damage

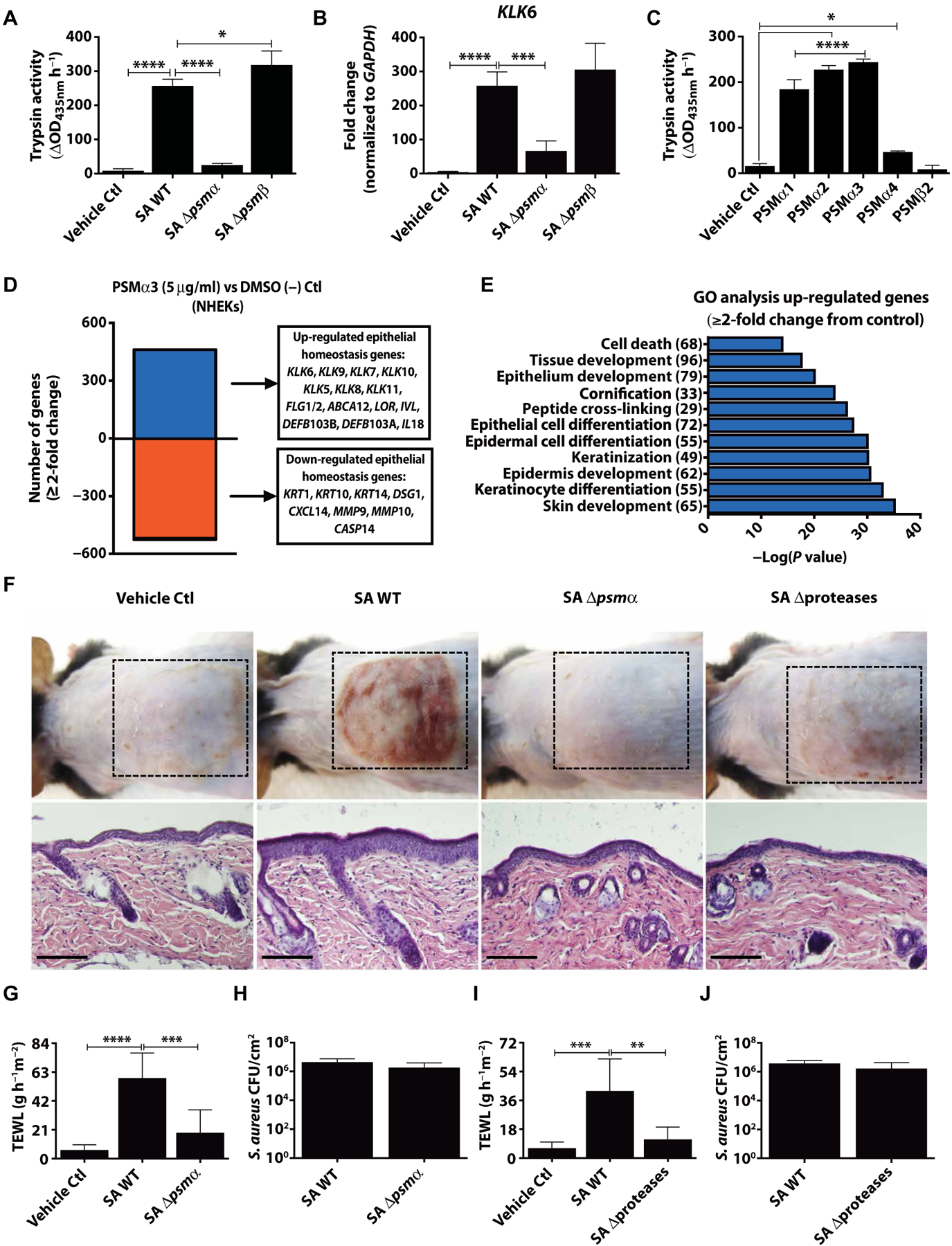

To understand the potential role of S. aureus PSMs on epidermal barrier function, we assessed normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) for their capacity to express proteolytic activity when exposed to S. aureus PSMs. Treatment with conditioned medium from wild-type S. aureus (USA300 LAC) or the same strain with targeted deletions in either the psmα or psmβ operons revealed that psmα was required for induction of trypsin-like serine protease activity and increased mRNA expression of kallikrein 6 (KLK6) (Fig. 1, A and B). We next tested synthetic PSMα1 to PSMα4 and PSMβ2 peptides that we synthesized on the basis of the genes encoded within the psmα and psmβ operons and found that all PSMα peptides could stimulate trypsin activity, whereas PSMβ2 could not (Fig. 1C). PSMα3, the strongest inducer of protease activity in NHEKs, induced trypsin activity and KLK6 mRNA expression in NHEKs in both a dose- and time-dependent manner and also induced cytokine production [IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and IL-1α] in human keratinocytes (fig. S1, A to D). Furthermore, transcriptional profiling by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of NHEKs exposed to PSMα3 showed that this toxin had a broad effect on expression of several genes related to the skin barrier, including multiple proteases [KLKs and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)], components of the physical barrier (filaggrin, desmoglein-1, loricrin, involucrin, and keratins), antimicrobial peptides, and proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 1, D and E, and fig. S1E). Deletion of psmα, but not psmβ, also reduced the production of IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1α from NHEKs (fig. S1, F to H).

Fig. 1. S. aureus PSMα induces keratinocyte protease activity and disrupts epithelial barrier homeostasis.

NHEKs were stimulated with 5% S. aureus USA300 LAC (SA) supernatant from overnight cultures [1 × 109 colony-performing units (CFU)] of wild-type (WT) and psmα (Δpsmα) or psmβ (Δpsmβ) knockout strains for 24 hours. Both (A) trypsin activity and (B) KLK6 mRNA expression compared to the housekeeping gene GAPDH were analyzed (n = 4). (C) PSM synthetic peptides were added to NHEKs for 24 hours to analyze changes in trypsin activity (n = 4). (D) Transcript analysis by RNA-seq and (E) gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes that changed ≥2-fold 24 hours after PSMα3 treatment. The number of genes in each category shown in parentheses. (F) Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were treated for 72 hours with 1 × 107 CFU SA WT (USA300 LAC) and corresponding SA Δpsmα, or SA USA300 LAC WT (AH1263) and corresponding SA Δproteases [SA WT in (F) representative of both SA WT strains]. Bacterial growth medium was used as a vehicle control. Dashed lines indicate treatment area. Scale bars, 200 μm (n = 6). (G to J) Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) or measurement of CFU/cm2 on mice after 72-hour treatment with initial 1 × 107 CFU of (G and H) SA WT (USA300 LAC) and corresponding SA Δpsmα or (I and J) SA WT [USA300 LAC (AH1263)] and corresponding SA Δproteases (n = 6). All experiments are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars are SEM. One-way ANOVA was used to determine statistical significance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Ctl, control.

To validate the role of the psmα operon on the epidermal barrier in vivo, mice were colonized on the skin surface for 72 hours with equal numbers of the S. aureus USA300 LAC wild type or the corresponding psmα mutant strain. S. aureus induced erythema, scaling, and epidermal thickening of murine skin in a psmα-dependent manner (Fig. 1F). Despite increased epidermal thickness, we observed an increase in TEWL, a well-established method to assess skin barrier damage after exposure to wild-type S. aureus, but not when psmα was absent (Fig. 1G). Skin barrier disruption of a fully differentiated epidermis in vivo was also dependent on the expression of protease activity by S. aureus. Using a mutant strain of S. aureus derived from the wild-type USA300 LAC (AH1263) parent strain that lacks all 10 major secreted proteases (AH1919) (24), we showed decreased injury and improved TEWL when S. aureus lacked protease activity, despite fully intact psmα expression (Fig. 1, F and H). An increase in epidermal trypsin activity, epidermal thickness, Klk6, and Il6, Il17a, and Il17f transcript expression was observed in mice exposed to wild-type S. aureus, but not when exposed to psmα or protease-deficient strains (fig. S2). A decreased inflammatory response to the protease-deficient mutant contrasted with the response of cultured NHEKs that showed only minor differences in endogenous protease activity induction (21) and no change to KLK6 expression or cytokine (IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1α) responses when conditioned medium from the protease-deficient mutant was applied (fig. S1, I and J). This suggests that S. aureus protease activity is necessary for psmα to activate keratinocytes when an intact stratum corneum is present. Despite changes in the skin barrier and inflammatory milieu, S. aureus survival on skin was not influenced by deletion of psmα or protease activity (Fig. 1, I and J). Together, these data show that both production of PSMα peptides and protease activity from S. aureus result in damage to the epidermal barrier, a critical step in promoting the skin inflammation seen in AD

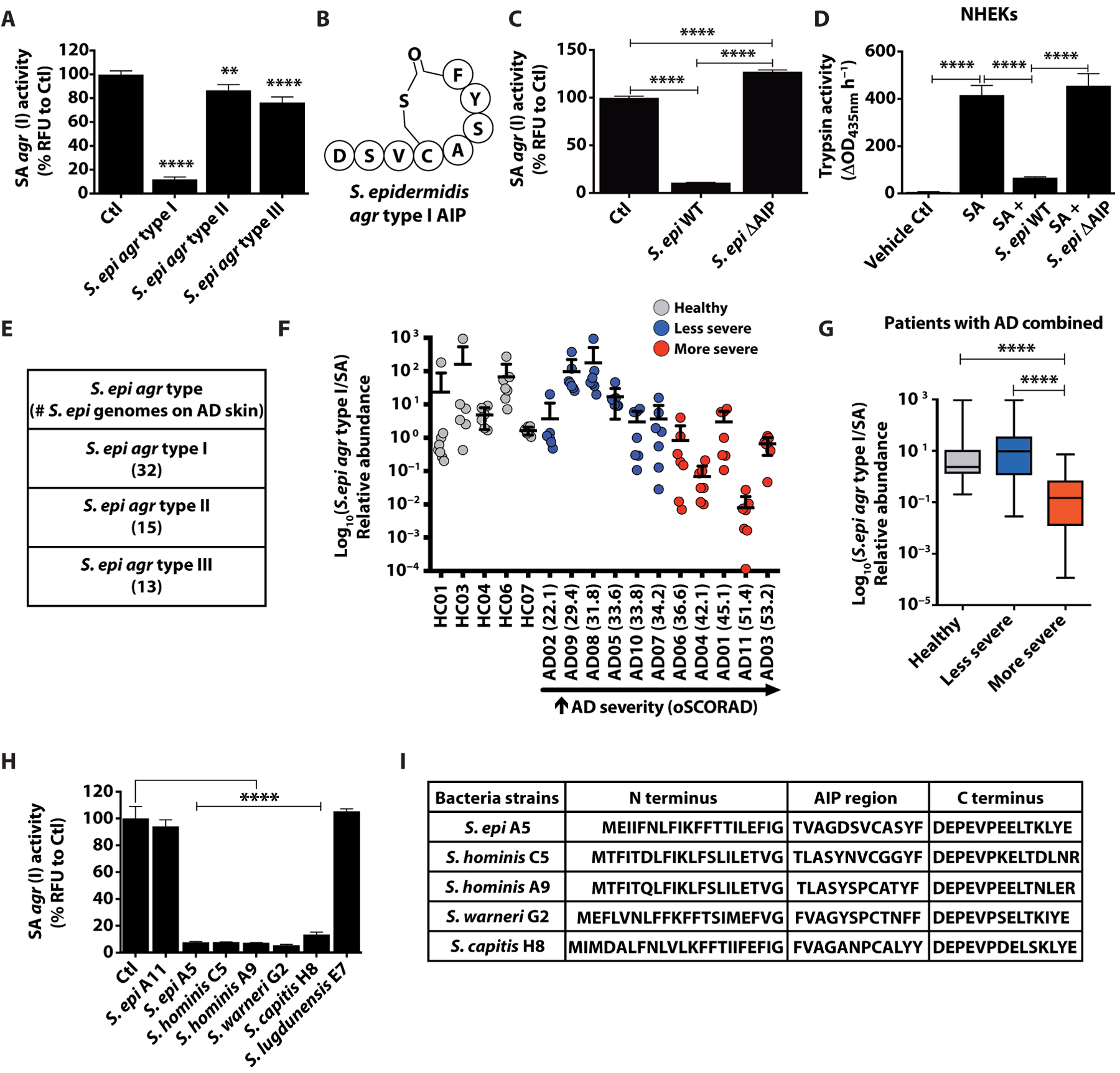

Staphylococcus epidermidis autoinducing peptide inhibits S. aureus agr activity

Both the S. aureus PSMα peptides and secreted proteases are under regulation of the accessory gene regulatory (agr) quorum sensing system. S. aureus clinical isolates have been found to have four distinct agr types, with agr type I being the most prominent in AD subjects (25, 26). A S. epidermidis agr type I laboratory isolate was previously revealed to produce an autoinducing peptide that could inhibit S. aureus agr types I to III but not type IV, but little is known of the influence of other agr types or the skin commensal community as a whole on S. aureus agr activity (27). To investigate this, conditioned culture supernatants from defined laboratory strains of S. epidermidis with agr types I (RP62A), II (1457), or III (8247) were first tested with a S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I P3-YFP reporter strain to explore whether S. epidermidis agr activity could influence the S. aureus agr system. S. epidermidis agr type I inhibited S. aureus agr activity, whereas S. epidermidis agr types II and III had little effect (Fig. 2, A and B). Targeted deletion of the S. epidermidis (RP62A) agr type I autoinducing peptide within the agrD gene region abolished the capacity of S. epidermidis to inhibit S. aureus agr activity (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, we observed that the increase in NHEK trypsin activity was inhibited when S. aureus was cultured in the presence of supernatant from wild-type S. epidermidis agr type I, but not by S. epidermidis lacking this autoinducing peptide (Fig. 2D). These experiments demonstrate that some S. epidermidis laboratory strains could inhibit the capacity of S. aureus to induce keratinocyte trypsin activity and may therefore be relevant to inflammation in AD

Fig. 2. S. epidermidis agr type I autoinducing peptide characterization and deficiency in AD skin.

(A) SA USA300 LAC agr type I P3-YFP activity after overnight culture (1 × 109 CFU) with 25% supernatant from overnight culture of S. epidermidis (S. epi) agr types I (RP62A), II (1457), and III (8247) (n = 4). (B) Structure of S. epidermidis agr type I autoinducing peptide (AIP). (C) Analysis of agr activity as in (A) with S. epidermidis agr type I (RP62A) WT or autoinducing peptide knockout (ΔAIP) strain supernatants (n = 4). (D) NHEK trypsin activity after culture for 24 hours with 5% SA supernatant grown overnight with or without S. epidermidis agr type I (RP62A) WT or autoinducing peptide knockout (ΔAIP) (n = 4). (E) Number (#) of S. epidermidis agr types I to III strains found on AD skin from metagenomic dataset. (F and G) Ratio of S. epidermidis agr type I to SA relative abundance on the combined analysis of all sites sampled from 5 healthy individuals and 11 AD subjects during flare and ranked from “least severe” to “most severe” based on oSCORAD. (H) Analysis of agr activity as in (A) after coculture overnight with 25% supernatant of overnight cultures (1 × 109 CFU) of clinical CoNS strains (n = 3). (I) Assessment of autoinducing peptide coding regions in agrD gene of the inhibitory CoNS strains. All experiments are representative of three independent experiments. All error bars are SEM. One-way ANOVA or an (nonparametric) unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test in (G) was used to determine statistical significance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

CoNS prevent S. aureus damage to AD skin

Having established the potential for a S. epidermidis agr type I strain to decrease the capacity of S. aureus to induce protease activity in human keratinocytes, we next investigated the abundance of S. epidermidis agr types on patients with AD. We analyzed previously published metagenomic data available from the skin microbiome of 5 healthy subjects and 11 subjects with AD (28). Of the 60 S. epidermidis strains detected on AD skin, the most frequent agr type was that of agr type I (Fig. 2E). Data were next stratified on the basis of severity [objective SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (oSCORAD)], and results were pooled from seven body sites. Comparison of the abundance of S. epidermidis agr type I to S. aureus showed that S. epidermidis agr type I became relatively less abundant in AD subjects with increased disease severity across all body sites (Fig. 2, F and G). Analysis by body site showed a similar trend at all locations, with the most frequent affected sites of the antecubital crease and popliteal crease showing the most notable association with global severity (fig. S3). These observations suggested that the relative abundance of S. epidermidis agr type I compared to S. aureus in the AD skin microbiome is associated with clinical disease. This association is consistent with a potential quorum sensing mechanism that would require an increased ratio of autoinducing peptides from S. epidermidis to inhibit S. aureus disease-promoting protease and toxin production.

Having established the function of a laboratory strain of S. epidermidis to inhibit the capacity of S. aureus to damage the epidermis, and observing that there was a lack of S. epidermidis agr type I strains relative to S. aureus in more severe AD, we next sought to determine whether quorum sensing interactions might exist between other members of the skin microbiome and S. aureus. We screened multiple clinical CoNS isolates from AD and healthy subjects for the capacity of culture supernatants from these isolates to inhibit S. aureus agr activity. This experiment revealed that diverse species other than S. epidermidis, including Staphylococcus hominis, Staphylococcus warneri, and Staphylococcus capitis, have potent inhibitory activity against S. aureus and encode putative autoinducing peptides (Fig. 2, H and I). We screened 144 clinical CoNS isolates from healthy individuals and 288 isolates from both nonlesional and lesional AD skin swabs and found that the frequency of CoNS strains that could inhibit S. aureus agr activity was similar across all subjects regardless of disease state (fig. S4, A and B). As CoNS from healthy skin often have the capacity to inhibit growth of S. aureus (29), culture supernatant was used at a 25% dilution that effectively inhibited agr but did not inhibit S. aureus growth (fig. S4C). These findings suggest that multiple diverse members of the skin microbial community may contribute to suppressing S. aureus agr activity.

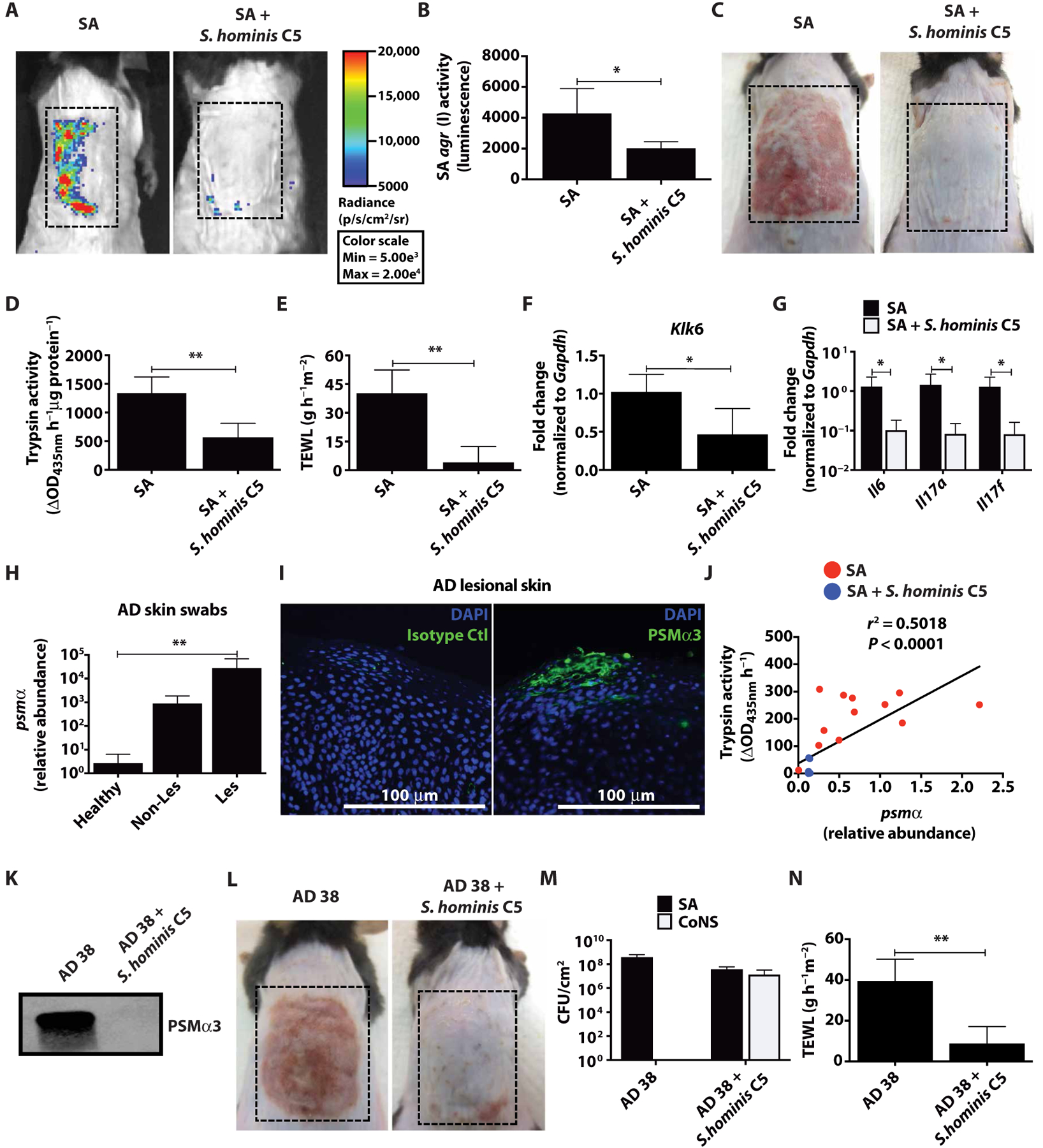

To establish whether quorum sensing interactions between CoNS and S. aureus can occur on live skin, S. aureus agr activity was assessed on mice by In Vivo Live Imaging (IVIS) using the S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I P3-Lux promoter strain. We chose S. hominis C5 as a model clinical CoNS isolate for the remainder of this study as this strain potently inhibited S. aureus agr type I activity but did not have antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, thus permitting accurate assessment of agr activity. Application of live S. hominis C5 together with S. aureus to mice at a 1:1 ratio resulted in potent inhibition of agr activity, inflammation, TEWL, trypsin activity, and decreased Klk6 and cytokine expression (Fig. 3, A to G). At a higher S. aureus to S. hominis ratio (10:1), the protective activity of S. hominis was lost (fig. S5, A and B). This was similar to the increase in AD severity seen in subjects with an increased ratio of S. aureus (Fig. 2F). Use of a clinical CoNS isolate that did not inhibit agr activity (S. epidermidis A11) did not prevent the capacity of S. aureus to promote barrier damage and inflammation (fig. S5, C and D). Co-application of S. hominis C5 did not decrease the abundance of S. aureus (fig. S5, B and D).

Fig. 3. Inhibition of S. aureus agr activity by clinical S. hominis isolate correlates with prevention of skin barrier damage and inflammation.

(A to C) SA USA300 LAC agr type I pAmi P3-Lux reporter strain (AH2759) (1 × 107 CFU) combined with or without live S. hominis C5 (1 × 107 CFU) was applied to murine back skin for 72 hours, and SA agr activity was assessed by changes in luminescence. Images are representative of n = 5; dashed boxes indicate treatment area. (D to G) Murine back skin after 72-hour bacteria treatment, assessed for changes in TEWL, trypsin activity, and Klk6 and cytokine (Il6, Il17a, and Il17f) mRNA expression normalized to housekeeping gene Gapdh (n = 5). (H) Relative abundance of SA psmα mRNA isolated from swabs of healthy (n = 6) and AD nonlesional and lesional skin (n = 5). (I) Detection of SA PSMα3 by immunofluorescence in epidermis of AD lesional skin (representative image with scale bar, 100 μm). (J) Clinical SA isolates from 11 patients were grown up to 18 hours (1 × 109 CFU) with or without 25% S. hominis C5 supernatant. psmα mRNA expression was measured at 8 hours, whereas trypsin activity was assessed from NHEKs treated 24 hours with 18-hour cultured SA (5%) supernatant (n = 3). (K) Immunoblot of culture supernatant from clinical SA isolate AD 38 grown overnight (1 × 109 CFU) with or without S. hominis C5 supernatant and probed for PSMα3. (L to N) SA AD 38 (1 × 107 CFU) was applied to murine back skin with or without S. hominis C5 (1 × 107 CFU) for 72 hours (n = 5) (dashed boxes indicate treatment area). Changes in CFU/cm2 of SA and CoNS, and TEWL are shown. All experiments are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. Student’s t tests, Pearson correlation coefficient (J), and an (nonparametric) unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test (H) were used to determine statistical significance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Sequence analysis of metagenomic data from patients with AD revealed that there was diversity in S. aureus agr types on patients with AD, with the most common being agr types I and II (fig. S6). We sought to determine whether S. aureus clinical isolates had an agr type allowing them to express PSMα peptides and induce damage to the epidermis similar to the laboratory isolate USA300 LAC. We screened skin swabs from healthy, nonlesional, and lesional patients with AD. The S. aureus psmα operon transcript was much more abundant in samples from patients with AD (Fig. 3H). S. aureus PSMα3 protein deposition was detected in the epidermis of lesional AD skin sections by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3I). Functional screening of 11 distinct clinical S. aureus isolates obtained from the lesional skin of 11 subjects with AD demonstrated that all of these strains were able to induce trypsin activity in NHEKs, and that the mRNA expression of the psmα operon correlated with the bacterial capacity to induce trypsin activity (Fig. 3J). S. hominis C5 supernatant inhibited S. aureus agr types I to III, but not type IV, and all of the 11 S. aureus isolates from AD subjects were identified as being agr type I or II (fig. S6). We found that S. hominis C5 could also prevent PSMα3 protein expression in a potent S. aureus AD isolate (AD 38) (Fig. 3K). Last, co-colonization of murine back skin with AD 38 and live S. hominis C5 (1:1 ratio) was shown to inhibit skin injury and inflammation without changing S. aureus abundance (Fig. 3, L to N). This treatment also prevented AD 38–induced trypsin activity, Klk6 expression, and cytokine expression (fig. S5, E to G). Overall, these data confirm expression of PSMα on AD skin and support the clinical relevance of our observations that CoNS can inhibit the agr activity and prevent S. aureus virulence factor production.

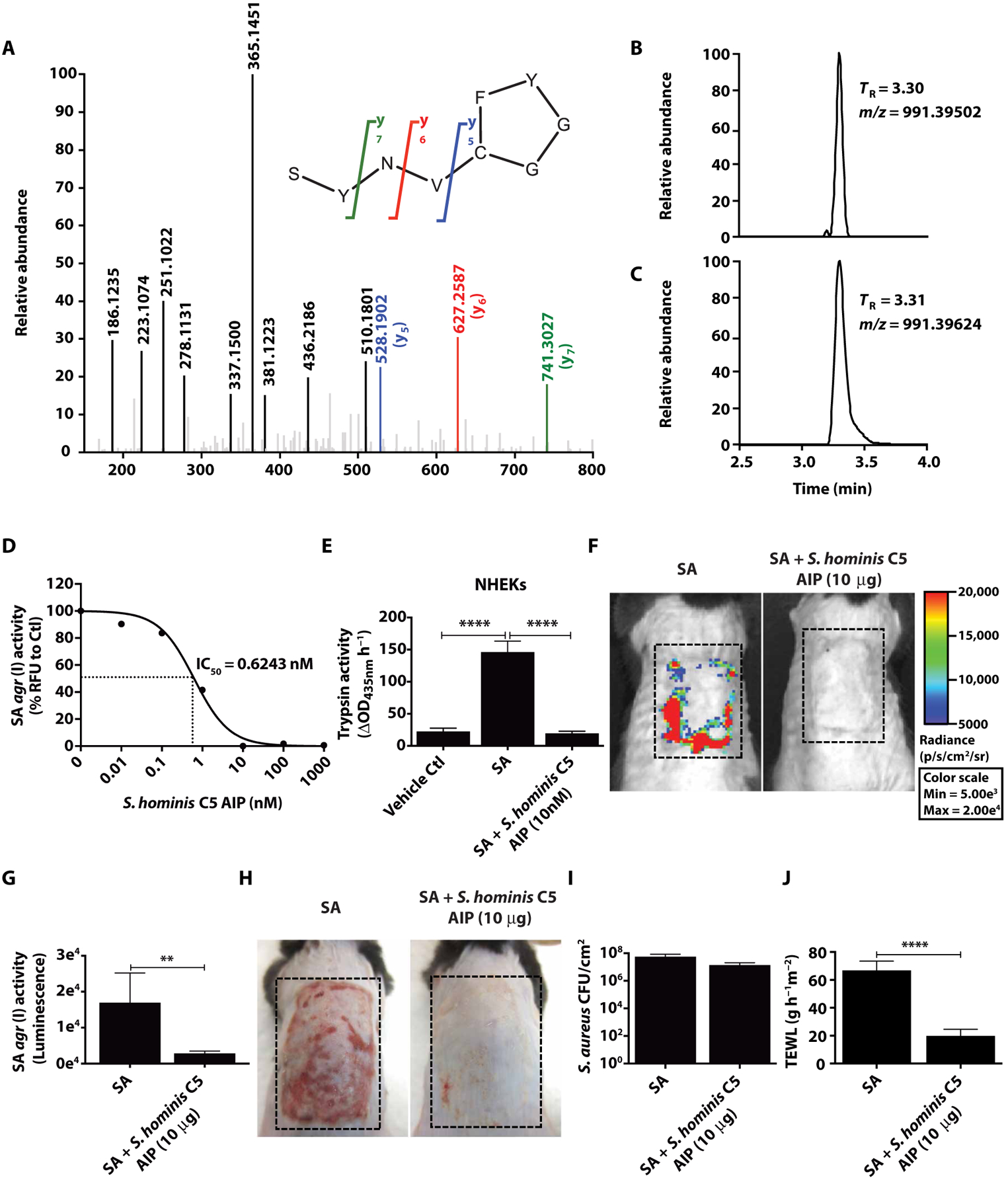

Purification of an autoinducing peptide from S. hominis and confirmation of activity

To further validate the conclusion that S. aureus agr inhibition was due to autoinducing peptide expression from the microbiome of human skin, we next identified the autoinducing peptide from the S. hominis C5 clinical isolate. This was accomplished by several initial biochemical isolation steps from crude S. hominis C5 supernatant followed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) of enriched fractions. Our purification and sequence analysis detected an autoinducing peptide sequence (S-Y-N-V-C-G-G-Y-F) with a cyclic ring between the C and F amino acids (Fig. 4, A to C). The identified sequence was consistent with an autoinducing peptide in the agrD coding region predicted by genomic DNA sequencing (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 4. Identification of an autoinducing peptide from a clinical S. hominis isolate that inhibits S. aureus agr activity.

(A) Determination of S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide sequence as SYNVCGGYF. The MS-MS spectrum obtained with the synthetic peptide is shown. Bolded fragment peaks and those indicated in color were identified in the MS-MS spectra for both the synthetic peptide and the spent growth medium sample (with difference in mass of <5 parts per million). Only matching fragments above 15% abundance are shown. Key features used for identification were the y5 (blue), y6 (red), and y7 (green) fragments of the cyclic autoinducing peptide. The selected-ion chromatograms for mass/charge ratio (m/z) 991.3984 ± 5 ppm for (B) bacteria culture and (C) synthetic autoinducing peptide in growth medium confirmed the retention time (TR) and accurate m/z of the predicted autoinducing peptide sequence. (D) Analysis of S. hominis C5 synthetic autoinducing peptide on SA USA300 LAC agr type I P3-YFP activity after an overnight culture (1 × 109 CFU) and IC50 value indicated by dotted lines at midpoint of the curve. (E) Measurement of NHEK trypsin activity after 24-hour incubation with 5% supernatant from overnight culture of SA with or without S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide (1 × 109 CFU) (n = 4). (F to H) SA USA300 LAC agr type I pAmi P3-Lux with or without S. hominis C5 synthetic autoinducing peptide was colonized (1 × 107 CFU) on murine back skin for 48 hours followed by analysis of agr activity (luminescence) and representative pictures of murine back skin after treatment (dashed lines represent treated areas) (n = 5). (I and J) SA CFU/cm2 and TEWL after treatment with S. hominis C5 synthetic autoinducing peptide. Data are representative of two experiments. Error bars are SEM. One-way ANOVA and Student’s t tests were used to determine statistical significance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To validate that this S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide could inhibit S. aureus agr activity, we generated a synthetic peptide and added it to the agr reporter strain. The synthetic autoinducing peptide potently inhibited S. aureus agr activity in a dose-dependent manner and showed a median inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.6243 nM (Fig. 4D). The synthetic autoinducing peptide also inhibited the capacity of this S. aureus strain to induce trypsin activity in NHEKs (Fig. 4E). When the synthetic autoinducing peptide was directly added to mouse skin colonized with S. aureus, agr activity was inhibited (Fig. 4, F and G). The synthetic autoinducing peptide also inhibited TEWL, Klk6, and cytokine expression induced on murine skin by S. aureus without inhibiting S. aureus abundance (Fig. 4, H to J, and fig. S7). These data confirm that an autoinducing peptide from a CoNS species resident on human skin can inhibit the agr activity of S. aureus, supporting the conclusion that interspecies quorum sensing mechanisms in the skin microbiome can protect against epidermal damage promoted by S. aureus.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided two interrelated mechanisms that shed new light on the development and control of AD. Our findings show that S. aureus PSMα peptides directly act on human keratinocytes, the main cell type responsible for establishment of the physical barrier of the skin. Exposure to PSMα leads to increased proteolytic activity in the epidermis, breakdown of the epidermal barrier, and subsequent skin inflammation. This observation explains how S. aureus residing on the skin surface can promote and exacerbate disease in the absence of the deep tissue invasion that defines infection. The second main finding from this study is based on earlier observations that PSMα is under control of the quorum sensing agr system (30). As autoinducing peptides from some laboratory bacterial species have been found to repress the S. aureus agr system (27, 31, 32), we hypothesized that such an interspecies interaction within the human skin microbiome may be a normal event to maintain homeostasis even if colonization with S. aureus can occur. Our data demonstrated that several different CoNS species, but not all strains within these species, encode autoinducing peptides that repress S. aureus agr activity. We showed that a beneficial CoNS strain or the synthetic CoNS autoinducing peptide was capable of inhibiting skin inflammation induced by S. aureus. We found that the stoichiometry of these interspecies interactions is unfavorable during disease flares in patients with AD, potentially indicating that when dysbiosis becomes extreme, these subjects then become exposed to PSMα. This is consistent with the direct observation of PSMα mRNA and protein deposition on lesional AD skin, an event that would not occur if CoNS autoinducing peptides were sufficiently abundant to suppress PSMα expression. Together, these observations show a previously unrecognized mechanism by which the diverse members of the skin microbiome can inhibit the disease-promoting activity of S. aureus. This observation could potentially explain why loss of bacterial diversity from excess abundance of S. aureus is strongly associated with increased disease severity.

S. aureus–secreted proteases, including the V8 protease, can directly cause skin barrier damage in mice (33) and play a vital role for S. aureus penetration into deeper layers of the epidermis and dermis, an event that triggers maximal induction of TH2 and TH17 inflammatory responses in murine AD models (22, 23). In this study, we found that S. aureus subverted the healthy murine epidermal barrier by the combined action of protease activity and production of PSMα peptides S. aureus–secreted proteases appeared essential to enable PSMα peptides to induce inflammation in vivo, where an intact stratum corneum protects underlying live keratinocytes. In vitro, S. aureus proteases had little to no effect on human keratinocytes, whereas PSMα expression was the major factor responsible for inducing keratinocyte trypsin activity. This suggests that S. aureus– secreted proteases are required for S. aureus to penetrate the skin in order for PSMα to stimulate keratinocytes. This process of inter-kingdom signaling explains how minor colonization by S. aureus could be amplified to promote major defects in the skin barrier. Future work is needed to better understand how S. aureus can penetrate the epidermal barrier including analyzing exactly what contribution each of the 10 known secreted S. aureus proteases including aureolysin, V8, staphopain A/B, and SplA-F have in inducing skin barrier damage.

We confirmed previous reports that PSMα peptides could induce an array of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1α, and TNFα, in human keratinocytes and skin. Keratinocyte secretion of IL-1 type cytokines was recently shown to be important for subsequent TH17 responses in murine skin (17, 18). TH17 responses have also been found to be clinically important in acute AD (34–36) and may explain an important component of how both S. aureus agr–regulated toxins such as PSMα and secreted proteases stimulate skin inflammation. Previous work has shown that a more TH2-dominant response in mice is observed after S. aureus colonization of ovalbumin-sensitized mice lacking filaggrin (22). This further supports the important interplay between environment, host genotype, and S. aureus colonization to drive human AD.

Here, we validated that the S. epidermidis agr type I autoinducing peptide was active against S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I and protective for human keratinocytes, whereas S. epidermidis agr types II and III were not active. Analysis of clinical samples from AD subjects demonstrated the presence of these strains on human skin and suggested that disease flare severity correlates with a decrease in the abundance of S. epidermidis agr type I relative to S. aureus, a condition that would promote PSMα expression and disease progression. One limitation of the current study is that the absolute abundance of autoinducing peptides and production of PSMα peptides were not measured during the course of disease flares. Such information would provide important supporting evidence that the quorum sensing interaction causes disease or promote remissions. In addition, despite the benefit displayed in this study by restoring commensal CoNS strains to the diseased skin phenotype to prevent S. aureus agr activity, more work is necessary to use this treatment as a potential therapeutic option. Several studies have eluded to biofilm formation being inversely regulated by the S. aureus agr system, with biofilms promoted by inhibition of agr (37, 38). Biofilms have been detected on subjects with AD (39), and their presence increases resistance of S. aureus to killing by host antimicrobials such as LL-37 (40). Therefore, although CoNS autoinducing peptides appear to be protective against skin inflammation induced by S. aureus, it is also possible that this promotes persistent colonization. This study also did not examine the efficacy of transplanted autoinducing peptide inhibitory CoNS strains to survive on diseased skin, or the stability of the synthetic CoNS autoinducing peptide on the normal skin surface. Understanding the efficacy of longterm application of the synthetic autoinducing peptides or CoNS application onto epidermal models is essential for human therapeutic application.

The data from the current study illustrate the complexity of interspecies and inter-kingdom communication on human skin by showing how multiple clinical CoNS isolates could prevent the capacity of S. aureus to induce skin barrier damage and inflammation. We showed that most, but not all, S. aureus colonies could induce epidermal damage. We also showed that the presence of live clinical CoNS isolates, or a synthetic autoinducing peptide identified in one strain, was protective against clinical S. aureus strains expressing PSMα. It is possible that additional, unknown chemical signals that regulate S. aureus agr activity may also exist on human skin

Together, we provide evidence that quorum sensing between some commensal CoNS species and S. aureus on human skin acts in a beneficial manner by inhibiting the negative consequences of S. aureus toxin production. This protective mechanism may act in parallel with the capacity of some CoNS strains to directly inhibit S. aureus survival (29). Because autoinducing peptide action does not limit S. aureus growth, evolutionary pressure to avoid agr inhibition is much different than the selective pressure for S. aureus to evolve antimicrobial resistance. By using both autoinducing peptide and antimicrobial strategies to compete with S. aureus, such CoNS strains could become a highly desirable member of the healthy human skin microbiome. These findings suggest that the pathophysiology of AD requires better knowledge of the failure of host skin to support these mutualistic relationships over the disease-promoting activity of S. aureus. Understanding how to optimize this may lead to improvements to existing therapeutic strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The objective of this study was to determine how components of the microbiome including S. aureus strains and CoNS species and strains promote or protect against epidermal damage in AD. This was done using commercial primary human keratinocytes, epicutaneous murine models, and bacteria harvested from human skin and through computational analysis of published skin microbiome sequencing. All experiments in this study using in vitro and in vivo techniques were carried out with a minimum n = 3 for biological replicates. Sample analysis was performed quantitatively, without assessment of power, in an unblinded manner and confirmed by at least two to three independent experiments as indicated in the figure legends. Primary data are reported in data file S1

Collection of bacteria from human subjects

All experiments involving human subjects were carried out according to protocols approved by University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Institutional Review Board (project no. 071032). Skin swabs and bacteria isolates from healthy volunteers and patients with AD used in this study were collected from a previous study at UCSD under the protocol above with prior patient consent (29). Briefly, collection of surface bacteria was done from a premeasured area (15 cm2) of lesional skin on the antecubital crease of subjects with AD. Swabs were immediately placed into a 3% tryptic soy broth (TSB) and 16.67% glycerol solution and frozen at −80°C. For collection of clinical S. aureus and CoNS isolates, swabs were rapidly thawed, vortexed, and serially diluted onto mannitol salt agar selection plates supplemented with 3% egg yolk. S. aureus was distinguished from CoNS according to mannitol metabolism and the egg yolk reaction as described previously, and isolates were stored at −80°C in the same solution as above for further analyses (29, 41). Confirmation of species of select CoNS strains was identified by full-genome sequencing analysis as indicated below.

Bacterial preparation

All bacteria used in this study are listed in table S1. All staphylococci (S. aureus and CoNS strains) were grown overnight (18 hours) to stationary phase in 3% TSB at 300 rpm in a 37°C incubator unless stated otherwise. This growth time for all staphylococci indicated about an OD600nm reading of 10 and 1 × 109 CFU. Specific strains were grown with antibiotic selection where indicated in table S1 at the following concentrations: Erm (5 μg/ml), Lcm (25 μg/ml), and Cm (10 μg/ml). For the treatment of bacterial supernatant on human keratinocytes or murine skin, bacteria cultured overnight were pelleted (15 min, 4000 rpm, room temperature) followed by filtered sterilization of the supernatant (0.22 μm). For mouse experiments with live bacteria colonization, bacterial CFU was approximated by OD600nm before application to mouse back skin followed by confirmation of the actual CFU the following day.

NHEK culture

NHEKs (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were cultured in EpiLife medium containing 60 μM CaCl2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1 EpiLife Defined Growth Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic [penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 U/ml), amphotericin B (250 ng/ml); Thermo Fisher Scientific] at 37°C, 5% CO2. NHEKs were only used for experiments between passages 3 and 5. For experiments, NHEKs were grown to 70% confluency followed by differentiation in high-calcium EpiLife medium (2 mM CaCl2) for 48 hours to simulate the upper layers of the epidermis. For bacterial supernatant treatments, differentiated NHEKs were treated with sterile-filtered bacterial supernatant at 5% by volume to EpiLife medium for 24 hours. Similarly, for synthetic PSM treatments, the peptides (5 to 50 μg/ml) were added to the NHEKs for 24 hours in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

S. aureus epicutaneous mouse model

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 (The Jackson Laboratory) mice were used for all experiments (n = 5 to 6 per condition), as specified in the figure legends. Mice were co-housed with n = 3 to 5 per cage for all experiments. All animal experiments were approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. S09074). Mouse hair was removed by shaving and applying Nair for 2 min followed by immediate removal with alcohol wipes. The skin barrier was allowed to recover from hair removal for 48 hours before application of bacteria. S. aureus (1 × 107 CFU) in 3% TSB was applied to murine skin for 48 to 72 hours at a 100-μl volume on a 2-cm2 piece of sterile gauze. Tegaderm was applied on top of gauze to hold in place for the duration of the treatment. For S. aureus agr inhibition experiments, live S. hominis C5 (1:1) or synthetic autoinducing peptides (10 μg) were combined with S. aureus in 3% TSB immediately before application on gauze.

Synthetic PSM preparation

All synthetic PSMs were produced by LifeTein. Peptides were produced at 95% purity with N-terminal formylation. PSM sequences were as follows:

PSMα1, fMGIIAGIIKVIKSLIEQFTGK; PSMα2, fMGIIAGIIKFIKGLIEKFTGK;

PSMα3, fMEFVAKLFKFFKDLLGKFLGNN; PSMα4, fMAIVGTIIKIIKAIIDIFAK;

PSMβ2, fMTGLAEAIANTVQAAQQHDSVKLGTSIVDIVANGVGLLGKLFGF.

Peptides were resuspended in DMSO and concentrated by SpeedVac into 500 mg of powder stocks stored at −80°C before reconstitution in DMSO for experiments.

S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide structure determination

We confirmed the structure of S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide as S-Y-N-V-c(C-G-G-Y-F) (calculated m/z, 991.3984) as follows. S. hominis C5 was cultured for 24 hours in 3% TSB medium and was partially purified using solid-phase extraction as follows. The bacteria sterile-filtered (0.22 μm) spent medium was inoculated with 80% ammonium sulfate for 1 hour followed by centrifugation and resuspension of the pellet in water. The fraction was further filtered using size-exclusion centrifugation and by collecting the <3-kDa filtrate followed by running the filtrate through a Sep Pak C18 column (Waters) collecting a 40% acetonitrile elution after discarding the flow through and 20% acetonitrile fractions. The 40% acetonitrile- eluted fraction was dried on a SpeedVac and resuspended in water. This partially purified fraction from the S. hominis C5 spent medium and medium-only control was analyzed in the positive ion mode using an Acquity ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters Corp.) coupled to a Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The medium control and S. hominis C5 fraction were injected directly into the UPLC-MS system. Samples were analyzed using a 7.5-μl injection volume and a 10-min acetonitrile/water gradient as described previously (42). MS-MS data were collected by subjecting the [M + H]+-ion m/z 991.3984 to higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation with a normalized collision energy of 25. The S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide sequence from the spent medium was determined to be S-Y-N-V-c(C-G-G-Y-F) and was synthesized by AnaSpec at 90% purity by high-performance liquid chromatography and resuspended in DMSO. The synthetic autoinducing peptide was confirmed to match the spent medium of S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide structure by running 0.05 mg/ml of the synthetic peptide side by side with the spent medium and measuring equivalent fragmentation patterns, retention times, and mass.

TEWL measurements

To determine damage to the epidermal skin barrier, TEWL of murine skin treated for 48 to 72 hours with S. aureus was measured using a Tewameter TM300 (C & K).

Trypsin activity analysis

NHEK conditioned medium was added at 50 μl to 96-well black-bottom plates (Corning) followed by addition of 150 μl of the peptide Boc- Val-Pro-Arg-AMC (trypsin-like substrate; Bachem) at a final concentration of 200 μM in 1× digestion buffer [10 mM tris-HCl (pH7.8)] and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Relative fluorescence intensity (excitation, 354 nm; emission, 435 nm) was analyzed with a SpectraMax Gemini EM fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For murine skin trypsin activity analysis, 0.5-cm2 full-thickness skin was bead-beat (2.0-mm zirconia beads, 2 × 30 s with 5 min after each) in 1 ml of 1 M acetic acid, followed by an overnight rotation at 4°C. Samples were centrifuged (10 min, 13,000 rpm, 4°C) and then added to a new microcentrifuge tube followed by protein concentration using a SpeedVac to remove all remaining acetic acid. Proteins were resuspended in molecular-grade water (500 μl) and rotated overnight at 4°C followed by another centrifugation. Clear protein lysates were added to a new tube, and bicinchoninic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) analysis was used to determine protein concentration. Last, 10 μg of total protein was added to a 96-well plate followed by analysis with the trypsin substrate as above.

S. aureus agr activity

Either the S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I P3-YFP (AH1677) or the S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I pAmi P3-Lux (AH2759) reporter strains were used to detect S. aureus agr activity. For in vitro experiments, S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I P3-YFP diluted to 1 × 106 CFU and added to 300 μl of 3% TSB along with 100 μl of sterile-filtered commensal supernatant (25% by volume) was cultured overnight and shaken (300 rpm) for 24 hours at 37°C. Bacteria were then diluted 1:20 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (200 μl final), and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (excitation, 495 nm; emission, 530 nm) was detected using the fluorometer as above. Bacterial density was determined using an OD600nm readout on a spectrophotometer. For murine experiments, S. aureus USA300 LAC agr type I pAmi P3-Lux luminescence activity was determined using a Spectrum IVIS machine. Luminescence intensity was assessed after an automatic 2-min exposure by measuring emitted photons (p/s/cm2/sr) using the Live Imaging software (PerkinElmer).

Microbiome data and comparative genomic analysis

We analyzed publicly available shotgun metagenomic data for AD skin (28). The relative abundance of S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains was obtained directly from the published supplementary material (www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/9/397/eaal4651/DC1). The agrD characterization analysis was performed on all 11 available AD patients with information at seven distinct body sites on flared AD skin (AD01 to AD11), with differences in AD severity based on oSCORAD. Both S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains detected from this dataset were classified by agr type through amino acid sequence comparison with known agr sequences within the agrD gene region (43).

Quantification and statistical analysis

The (nonparametric) unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test was used for statistical significance analysis of AD patient metagenomic data in Fig. 2G and AD skin swabs analysis of psmα expression in Fig. 3H and fig. S4. All other figures used Student’s t tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for statistical analysis, as indicated in the figure legends. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad). All data were presented as means ± SEM, and a P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank M. Otto (NIH) for providing the PSM knockout strains of S. aureus for this study and J. M. Kahlenberg (University of Michigan) for providing guidance on synthetic PSM production.

Funding: This work was funded by The Atopic Dermatitis Research Network NIH U19 AI117673 (to R.L.G.), R01AI116576 (to R.L.G.), R01AR064781 (to R.L.G.), T32AR062496 (to M.R.W.), R01AR064781-04S1 (to M.R.W.), VA I01 BX002711 (to A.R.H.), and R21 AI133089 (to A.R.H.).

Footnotes

stm.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/11/490/eaat8329/DC1

Materials and Methods

Fig. S1. S. aureus PSMα changes essential barrier gene and cytokine expression in human keratinocytes.

Fig. S2. S. aureus PSMα and proteases are responsible for barrier damage and induction of inflammation on murine skin.

Fig. S3. Effect of AD skin disease severity on S. epidermidis agr type I to S. aureus relative abundance by body site.

Fig. S4. Clinical CoNS isolates inhibit S. aureus agr activity without affecting growth.

Fig. S5. S. hominis C5 live bacteria specifically inhibit S. aureus–mediated barrier damage and inflammation.

Fig. S6. S. hominis C5 inhibits S. aureus agr types I to III but not type IV.

Fig. S7. S. hominis C5 autoinducing peptide inhibits S. aureus–driven inflammation and barrier damage.

Table S1. Bacteria strains and plasmids used.

Table S2. Primers used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction and allelic replacement. Data file S1. Raw data (available as Excel file).

Competing interests: M.R.W. and R.L.G. are co-inventors of UCSD technology related to the bacterial quorum sensing inhibition therapy discussed here under patent PCT/US18/49237 titled “Molecular bacteriotherapy to control skin enzymatic activity.” R.L.G. is a co-founder, scientific advisor, consultant, and has equity in MatriSys Biosciences, and is a consultant, receives income from, and has equity in Sente.

Data and materials availability: All data associated with this study are present in the paper or Supplementary Materials. RNA-seq data are available through the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) online data repository under accession number GSE124818. Bacterial genome sequences are available at NCBI BioProject under accession PRJNA514867. Primary data are reported in data file S1.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM, The burden of atopic dermatitis in US adults: Health care resource utilization data from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 78, 54–61.e1 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI, Inpatient financial burden of atopic dermatitis in the United States. J. Invest. Dermatol 137, 1461–1467 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, Goudie DR, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Smith FJ, O’Regan GM, Watson RM, Cecil JE, Bale SJ, Compton JG, DiGiovanna JJ, Fleckman P, Lewis-Jones S, Arseculeratne G, Sergeant A, Munro CS, El Houate B, McElreavey K, Halkjaer LB, Bisgaard H, Mukhopadhyay S, McLean WH, Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet 38, 441–446 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Benedetto A, Rafaels NM, McGirt LY, Ivanov AI, Georas SN, Cheadle C, Berger AE, Zhang K, Vidyasagar S, Yoshida T, Boguniewicz M, Hata T, Schneider LC, Hanifin JM, Gallo RL, Novak N, Weidinger S, Beaty TH, Leung DY, Barnes KC, Beck LA, Tight junction defects in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 127, 773–786.e1-7 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato A, Fukai K, Oiso N, Hosomi N, Murakami T, Ishii M, Association of SPINK5 gene polymorphisms with atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. British J. Dermatol 148, 665–669 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meylan P, Lang C, Mermoud S, Johannsen A, Norrenberg S, Hohl D, Vial Y, Prod’hom G, Greub G, Kypriotou M, Christen-Zaech S, Skin colonization by Staphylococcus aureus precedes the clinical diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in infancy. J. Invest. Dermatol 137, 2497–2504 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy EA, Connolly J, Hourihane JO, Fallon PG, McLean WH, Murray D, Jo JH, Segre JA, Kong HH, Irvine AD, Skin microbiome before development of atopic dermatitis: Early colonization with commensal staphylococci at 2 months is associated with a lower risk of atopic dermatitis at 1 year. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 139, 166–172 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leyden JJ, Marples RR, Kligman AM, Staphylococcus aureus in the lesions of atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol 90, 525–530 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsterholm M, Strömbeck L, Ljung A, Karami N, Widjestam J, Gillstedt M, Åhren C, Faergemann J, Variation in staphylococcus aureus colonization in relation to disease severity in adults with atopic dermatitis during a five-month follow-up. Acta Derm. Venereol 97, 802–807 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong JQ, Lin L, Lin T, Hao F, Zeng FQ, Bi ZG, Yi D, Zhao B, Skin colonization by Staphylococcus aureus in patients with eczema and atopic dermatitis and relevant combined topical therapy: A double-blind multicentre randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol 155, 680–687 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascolini C, Sinagra J, Pecetta S, Bordignon V, De Santis A, Cilli L, Cafiso V, Prignano G, Capitanio B, Passariello C, Stefani S, Cordiali-Fei P, Ensoli F, Molecular and immunological characterization of Staphylococcus aureus in pediatric atopic dermatitis: Implications for prophylaxis and clinical management. Clin. Dev. Immunol 2011, 718708 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawashima T, Noguchi E, Arinami T, Yamakawa-Kobayashi K, Nakagawa H, Otsuka F, Hamaguchi H, Linkage and association of an interleukin 4 gene polymorphism with atopic dermatitis in Japanese families. J. Med. Genet 35, 502–504 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsunemi Y, Saeki H, Nakamura K, Sekiya T, Hirai K, Kakinuma T, Fujita H, Asano N, Tanida Y, Wakugawa M, Torii H, Tamaki K, Interleukin-13 gene polymorphism G4257A is associated with atopic dermatitis in Japanese patients. J. Dermatol. Sci 30, 100–107 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, Grant AV, Boguniewicz M, Debenedetto A, Schneider L, Beck LA, Barnes KC, Leung DY, Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 120, 150–155 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nomura I, Goleva E, Howell MD, Hamid QA, Ong PY, Hall CF, Darst MA, Gao B, Boguniewicz M, Travers JB, Leung DY, Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis, as compared to psoriasis, skin prevents induction of innate immune response genes. J. Immunol 171, 3262–3269 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsianakas A, Luger TA, The anti-IL-4 receptor alpha antibody dupilumab: Facing a new era in treating atopic dermatitis. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 15, 1657–1660 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Archer NK, Dillen CA, Wang Y, Ashbaugh AG, Ortines RV, Kao T, Lee SK, Cai SS, Miller RJ, Marchitto MC, Zhang E, Riggins DP, Plaut RD, Stibitz S, Geha RS, Miller LS, Staphylococcus aureus epicutaneous exposure drives skin inflammation via IL-36-mediated T cell responses. Cell Host Microbe 22, 653–666.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa S, Matsumoto M, Katayama Y, Oguma R, Wakabayashi S, Nygaard T, Saijo S, Inohara N, Otto M, Matsue H, Nunez G, Nakamura Y, Staphylococcus aureus virulent PSMα peptides induce keratinocyte alarmin release to orchestrate IL-17-dependent skin inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 22, 667–677.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura Y, Oscherwitz J, Cease KB, Chan SM, Muñoz-Planillo R, Hasegawa M, Villaruz AE, Cheung GY, McGavin MJ, Travers JB, Otto M, Inohara N, Nuñez G, Staphylococcus δ-toxin induces allergic skin disease by activating mast cells. Nature 503, 397–401 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syed AK, Reed TJ, Clark KL, Boles BR, Kahlenberg JM, Staphylococcus aureus phenol-soluble modulins stimulate the release of proinflammatory cytokines from keratinocytes and are required for induction of skin inflammation. Infect. Immun 83, 3428–3437 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams MR, Nakatsuji T, Sanford JA, Vrbanac AF, Gallo RL, Staphylococcus aureus induces increased serine protease activity in keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol 137, 377–384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakatsuji T, Chen TH, Two AM, Chun KA, Narala S, Geha RS, Hata TR, Gallo RL, Staphylococcus aureus exploits epidermal barrier defects in atopic dermatitis to trigger cytokine expression. J. Invest. Dermatol 136, 2192–2200 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakatsuji T, Chiang HI, Jiang SB, Nagarajan H, Zengler K, Gallo RL, The microbiome extends to subepidermal compartments of normal skin. Nat. Commun 4, 1431 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wormann ME, Reichmann NT, Malone CL, Horswill AR, Grundling A, Proteolytic cleavage inactivates the Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid synthase. J. Bacteriol 193, 5279–5291 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung HJ, Jeon HS, Sung H, Kim MN, Hong SJ, Epidemiological characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from children with eczematous atopic dermatitis lesions. J. Clin. Microbiol 46, 991–995 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lomholt H, Andersen KE, Kilian M, Staphylococcus aureus clonal dynamics and virulence factors in children with atopic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol 125, 977–982 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otto M, Echner H, Voelter W, Gotz F, Pheromone cross-inhibition between Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun 69, 1957–1960 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byrd AL, Deming C, Cassidy SKB, Harrison OJ, Ng WI, Conlan S, NISC Comaprative Sequencing Program, Belkaid Y, Segre JA, Kong HH, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strain diversity underlying pediatric atopic dermatitis. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaal4651 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakatsuji T, Chen TH, Narala S, Chun KA, Two AM, Yun T, Shafiq F, Kotol PF, Bouslimani A, Melnik AV, Latif H, Kim JN, Lockhart A, Artis K, David G, Taylor P, Streib J, Dorrestein PC, Grier A, Gill SR, Zengler K, Hata TR, Leung DY, Gallo RL, Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic dermatitis. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaah4680 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan BA, Yeh AJ, Cheung GY, Otto M, Investigational therapies targeting quorum-sensing for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 24, 689–704 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canovas J, Baldry M, Bojer MS, Andersen PS, Gless BH, Grzeskowiak PK, Stegger M, Damborg P, Olsen CA, Ingmer H, Corrigendum: Cross-talk between Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococcal species via the agr quorum sensing system. Front. Microbiol 8, 1949 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paharik AE, Parlet CP, Chung N, Todd DA, Rodriguez EI, Van Dyke MJ, Cech NB, Horswill AR, Coagulase-negative staphylococcal strain prevents Staphylococcus aureus colonization and skin infection by blocking quorum sensing. Cell Host Microbe 22, 746–756.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirasawa Y, Takai T, Nakamura T, Mitsuishi K, Gunawan H, Suto H, Ogawa T, Wang XL, Ikeda S, Okumura K, Ogawa H, Staphylococcus aureus extracellular protease causes epidermal barrier dysfunction. J. Invest. Dermatol 130, 614–617 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Cesare A, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO, A role for Th17 cells in the immunopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis? J. Invest. Dermatol 128, 2569–2571 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esaki H, Brunner PM, Renert-Yuval Y, Czarnowicki T, Huynh T, Tran G, Lyon S, Rodriguez G, Immaneni S, Johnson DB, Bauer B, Fuentes-Duculan J, Zheng X, Peng X, Estrada YD, Xu H, de Guzman Strong C, Suarez-Farinas M, Krueger JG, Paller AS, Guttman-Yassky E, Early-onset pediatric atopic dermatitis is TH2 but also TH17 polarized in skin. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol 138, 1639–1651 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koga C, Kabashima K, Shiraishi N, Kobayashi M, Tokura Y, Possible pathogenic role of Th17 cells for atopic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol 128, 2625–2630 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boles BR, Horswill AR, Agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLOS Pathog. 4, e1000052 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vuong C, Saenz HL, Götz F, Otto M, Impact of the agr quorum-sensing system on adherence to polystyrene in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis 182, 1688–1693 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen HB, Vaze ND, Choi C, Hailu T, Tulbert BH, Cusack CA, Joshi SG, The presence and impact of biofilm-producing staphylococci in atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 150, 260–265 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonesson A, Przybyszewska K, Eriksson S, Morgelin M, Kjellstrom S, Davies J, Potempa J, Schmidtchen A, Identification of bacterial biofilm and the Staphylococcus aureus derived protease, staphopain, on the skin surface of patients with atopic dermatitis. Sci. Rep 7, 8689 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H, Tajima A, Seo H, Takada K, Agata T, Mizunoe Y, Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature 465, 346–349 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todd DA, Parlet CP, Crosby HA, Malone CL, Heilmann KP, Horswill AR, Cech NB, Signal biosynthesis inhibition with ambuic acid as a strategy to target antibiotic-resistant infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 61, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olson ME, Todd DA, Schaeffer CR, Paharik AE, Van Dyke MJ, Buttner H, Dunman PM, Rohde H, Cech NB, Fey PD, Horswill AR, Staphylococcus epidermidis agr quorum-sensing system: Signal identification, cross talk, and importance in colonization. J. Bacteriol 196, 3482–3493 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costa SK, Donegan NP, Corvaglia AR, Francois P, Cheung AL, Bypassing the restriction system to improve transformation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol 199, e00271–17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monk IR, Shah IM, Xu M, Tan MW, Foster TJ, Transforming the untransformable: Application of direct transformation to manipulate genetically Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. MBio 3, e00277–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnaud M, Chastanet A, Débarbouillé M, New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 70, 6887–6891 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langmead B, Salzberg SL, Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA, SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol 19, 455–477 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Parrello B, Shukla M, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F, Stevens R, The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D206–D214 (2013S). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thoendel M, Kavanaugh JS, Flack CE, Horswill AR, Peptide signaling in the staphylococci. Chem. Rev 111, 117–151 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilot P, Lina G, Cochard T, Poutrel B, Analysis of the genetic variability of genes encoding the RNA III-activating components Agr and TRAP in a population of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cows with mastitis. J. Clin. Microbiol 40, 4060–4067 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang R, Braughton KR, Kretschmer D, Bach TH, Queck SY, Li M, Kennedy AD, Dorward DW, Klebanoff SJ, Peschel A, DeLeo FR, Otto M, Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat. Med 13, 1510–1514 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Figueroa M, Jarmusch AK, Raja HA, El-Elimat T, Kavanaugh JS, Horswill AR, Cooks RG, Cech NB, Oberlies NH, Polyhydroxyanthraquinones as quorum sensing inhibitors from the guttates of Penicillium restrictum and their analysis by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Nat. Prod 77, 1351–1358 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muhs A, Lyles JT, Parlet CP, Nelson K, Kavanaugh JS, Horswill AR, Quave CL, Virulence inhibitors from Brazilian peppertree block quorum sensing and abate dermonecrosis in skin infection models. Sci. Rep 7, 42275 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malone CL, Boles BR, Lauderdale KJ, Thoendel M, Kavanaugh JS, Horswill AR, Fluorescent reporters for Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Methods 77, 251–260 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sully EK, Malachowa N, Elmore BO, Alexander SM, Femling JK, Gray BM, DeLeo FR, Otto M, Cheung AL, Edwards BS, Sklar LA, Horswill AR, Hall PR, Gresham HD, Selective chemical inhibition of agr quorum sensing in Staphylococcus aureus promotes host defense with minimal impact on resistance. PLOS Pathog. 10, e1004174 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.