Abstract

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a key role in maintaining blood pressure homeostasis, as well as fluid and salt balance. Angiotensin II, a key effector peptide of the system, causes vasoconstriction and exerts multiple biological functions. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) plays a central role in generating angiotensin II from angiotensin I, and capillary blood vessels in the lung are one of the major sites of ACE expression and angiotensin II production in the human body. The RAS has been implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis, both commonly seen in chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive lung disease. Recent studies indicate that the RAS also plays a critical role in acute lung diseases, especially acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ACE2, a close homologue of ACE, functions as a negative regulator of the angiotensin system and was identified as a key receptor for SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus infections. In the lung, ACE2 protects against acute lung injury in several animal models of ARDS. Thus, the RAS appears to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. Indeed, increasing ACE2 activity might be a novel approach for the treatment of acute lung failure in several diseases.

Introduction

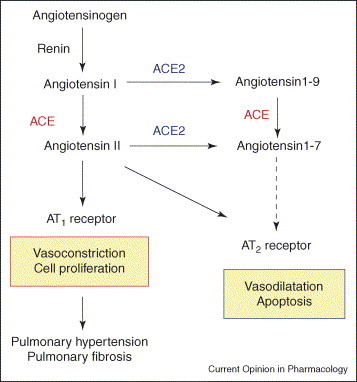

For many decades, the roles of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) have been studied in physiology and multiple disorders, in particular cardiovascular diseases [1, 2]. Angiotensin II (ANG II), a key effector peptide of the RAS, exerts multiple biological functions including the vasoconstriction and sodium balance involved in blood pressure homeostasis. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) plays a central role in generating ANG II from angiotensin I (ANG I) [3, 4] (Figure 1 ), and ACE inhibitors or ANG II receptor blockers exhibit beneficial effects in cardiovascular diseases. Capillary blood vessels in the lung are a major site of high-level expression of ACE [5]. Thus, the lung is an important organ in generating circulating ANG II, acting as a classical circulation-borne endocrine system. In contrast to this endocrine RAS model, numerous studies have highlighted the importance of local RASs [6]. For example, an increase in endothelial ACE expression in the muscularized intra-acinar arteries of lungs was shown both in patients with pulmonary hypertension [7] and in rats with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension [8]. In addition to ACE, other components of the RAS are expressed in lungs, including renin [9], angiotensinogen [10] and ANG II receptors [11].

Figure 1.

Current view of the RAS in pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis. ANG I serves as a substrate for both ACE and ACE2. ANG II is known to act as vasoconstrictor as well as a mitogen for smooth muscle cells or fibroblasts, mainly through the AT1 receptor. The function of angiotensin-(1–9) is not well understood. Both ACE and ACE2 are involved in the production of the vasodilator peptide angiotensin-(1–7).

In 2000, ACE2, a homologue of ACE, was identified; its discovery instantaneously added a new complexity to the RAS [12, 13]. Although ACE2 functions similarly to ACE as a carboxypeptidase, ACE2 has a different substrate specificity [12, 13, 14], shown by in vitro analyses using recombinant ACE2 protein. Whereas ACE removes dipeptides from the C-terminus of peptide substrates, generating the octapeptide ANG II from the decapeptide ANG I [3, 15], ACE2 cleaves a single residue from ANG II, generating angiotensin-(1–9) [12, 13], and a single residue from ANG II to generate angiotensin-(1–7) [12]. Genetic inactivation of ACE using homologous recombination results in a phenotype characterized by spontaneous hypotension, reduced male fertility and kidney malformation [16]. By contrast, targeted disruption of murine ACE2 resulted in increased systemic ANG II levels and impaired cardiac contractility in aged mice [17]. Loss of ACE on an ACE2 background reversed this cardiac phenotype [17]. Thus, ACE2 appears to be a negative regulator of the RAS and counterbalances the function of ACE (Figure 1).

The importance of the RAS in lung diseases has recently re-emerged since the identification of ACE2 as a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus receptor. During several months of 2003, SARS — a newly identified illness — spread rapidly from China throughout the world, causing more than 800 deaths [18, 19]. A novel coronavirus was identified as the SARS pathogen, which triggered atypical pneumonia characterized by high fever and severe dyspnea [18, 19]. The death rate following SARS coronavirus exposure approached almost 10% of infected people owing to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is the most severe form of acute lung injury and is characterized by pulmonary oedema, accumulation of inflammatory cells and severe hypoxia [20, 21]. Clinical as well as experimental animal studies have implicated ACE in the pathogenesis of ARDS [22, 23, 24]. ACE2 is expressed in the lungs of healthy and diseased humans [25], and recent ARDS and SARS studies have shown that ACE2 protects murine lungs from severe acute injury [26••, 27••]. Importantly, these experiments also revealed that ACE2 is an essential receptor for SARS infections in vitro and in vivo [27••, 28]. In this review, we review the role of the RAS, in particular of the SARS receptor ACE2, in lung diseases, focusing on pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis and acute lung injury. The possible applications of blocking the RAS and/or modulating ACE2 for the treatment of lung diseases are discussed.

Pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension is characterized by elevations in pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance caused by multiple etiologies, including primary pulmonary hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), high altitude or pulmonary embolism. Abnormal pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary vascular remodeling are major pathological features seen in most forms of pulmonary hypertension [29, 30]. Although ANG II is well known as a potent vasopressor peptide, in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension ANG II seems to play a role in pulmonary vascular remodeling rather than pulmonary vasoconstriction. In in vitro cell culture models, ANG II has been shown to directly cause growth/proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells largely through ANG II type I (AT1), rather than through type II (AT2), receptors [31] (Figure 1). In pulmonary hypertension in vivo, the expression of ACE is increased in the endothelial layer of small, as well as elastic, pulmonary arteries [7, 32]. In addition, in hypoxic, but not monocrotaline-treated [33], pulmonary hypertensive rats, both ANG II binding and the number of AT1 receptors are increased [34, 35].

In human patients, an association between an ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism (the D allele of the human ACE gene confers increased ACE activity in plasma) and pulmonary hypertension has been reported; this association is, however, controversial. For instance, one study showed that the ACE D/D genotype is associated with less right ventricular hypertrophy [36], whereas another reported a correlation between the ACE D/D genotype and the severity of symptoms [37]. Pharmacologic treatment of animals with either an ACE blocker or an ANG II receptor antagonist inhibited pulmonary vascular remodeling associated with the development of pulmonary hypertension in chronically hypoxic rats or mice [38, 39] or in monocrotaline-treated rats [40]. By contrast, tissue ACE-deficient mice, which exhibit undetectable lung ACE activity but retain ∼34% of the ACE activity in plasma, show the same remodeling of pulmonary arterioles as do wild-type mice [41]. In addition, despite earlier studies of acute ACE inhibition [42, 43, 44], a recent pilot study on patients with pulmonary hypertension secondary to COPD showed that treatment with the AT1 receptor blocker losartan (50 mg) showed no statistically significant beneficial effect in terms of pulmonary artery pressure, exercise capacity or breathlessness score [45]. The discrepancy between hypoxic rat studies and this human trial might be caused by differences in the pathogenesis of hypoxic rats versus patients with COPD-related pulmonary hypertension. Further studies are required to solve these important issues.

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is a frequent response to insults or injuries to the lung. Etiologies include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, irradiation-induced pneumonitis or ARDS. Excess deposition of extracellular matrix proteins is a key feature of interstitial fibrosis in the lung. The pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis includes endothelial and epithelial cell injury, influx of inflammatory cells and the production of chemical mediators leading to the proliferation and activation of fibroblasts [46, 47]. Although there are various initiating mechanisms and etiologies, the terminal phases of fibrosis are commonly characterized by the proliferation and progressive accumulation of connective tissue replacing normal functional parenchyma.

ANG II immunoreactivity is also significantly increased within lung fibroblasts, macrophages and bronchiolar and alveolar epithelium after irradiation [48]. In addition, angiotensinogen is produced by fibroblasts from fibrotic but not normal human lung. ANG II upregulates the expression of the profibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor-β1, which is involved in both the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and the accumulation of collagen [49] (Figure 1). An in vivo role for ANG II in pulmonary fibrosis has been implied from animal models with bleomycin- or irradiation-mediated lung injury. In bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats or mice, ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers can attenuate epithelial apoptosis, interstitial fibrosis and collagen deposition [50, 51, 52]. In irradiation-induced lung fibrosis, ACE inhibitors attenuate endothelial dysfunction and fibrosis in rats [53]. Conversely, retrospective comparison of the incidence of irradiation-induced lung injury between subjects who took ACE inhibitors and those who did not, failed to reveal a protective effect [54]. However, serum concentrations of ACE inhibitors used by subjects in the human study would be expected to be considerably less than those achieved in the animal models cited above. As there are no published prospective or retrospective studies regarding the use of other ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers in human pulmonary fibrosis induced by factors other than irradiation, it is therefore still unclear if inhibition of the RAS would indeed have beneficial effects on lung fibrosis.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome/acute lung injury

ARDS is the most severe form of acute lung injury, and affects approximately one million individuals worldwide/year with a mortality rate of at least 30–50% [20, 21]. ARDS can be triggered by multiple diseases such as sepsis, aspiration, trauma, acute pancreatitis, or pneumonias following infections with SARS coronavirus or avian and human influenza viruses. Recent cohort studies of ARDS showed a significant association between an ACE insertion/deletion polymorphism and the susceptibility and outcome of ARDS [23, 24]. The D/D genotype frequency was increased in patients with ARDS compared with a control cohort [23]. In addition, the ACE D/D allele was significantly associated with mortality in the ARDS group [23]. Another study showed that patients carrying the ACE I/I genotype have a significantly increased survival rate [24]. Thus, from the results of inhibitor experiments in rodents [22] and ACE allelic correlation studies in humans [23, 24], it has been suggested that the RAS could play a role in acute lung failure.

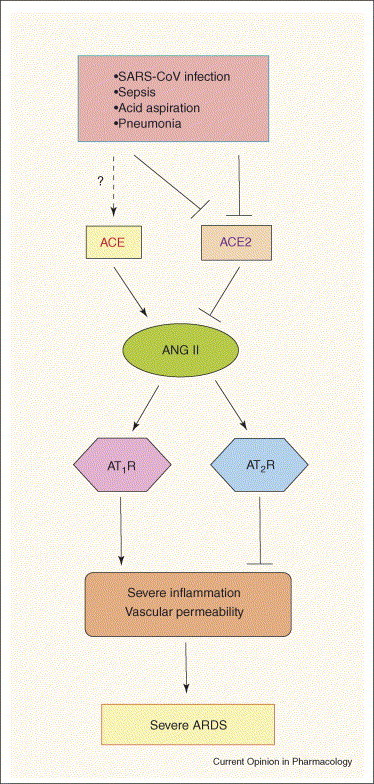

Our group has investigated the role of ACE2 in ARDS by using ace2 knockout mice. In acid-aspiration-induced ARDS, endotoxin-induced ARDS and peritoneal sepsis-induced ARDS, ace2 knockout mice exhibited severe disease compared with control mice that express ACE2 [26••]. Loss of ACE2 expression in mutant mice resulted in enhanced vascular permeability, increased lung edema, neutrophil accumulation and worsened lung function. Importantly, treatment with catalytically active, but not enzymatically inactive, recombinant ACE2 protein improved the symptoms of acute lung injury in wild-type mice, as well as in ace2 knockout mice [26••]. Thus, ACE2 plays a protective role in acute lung injury. Mechanistically, the negative regulation of ANG II levels by ACE2 accounts, in part, for the protective function of ACE2 in ARDS. For example, AT1 receptor inhibitor treatment or additional ace gene deficiency on an ace2 knockout background rescues the severe phenotype of ace2 single mutant mice in acute lung injury [26••]. In addition, ace knockout mice and AT1a receptor knockout mice showed improved symptoms of acute lung injury [26••]. Therefore, in acute lung injury, ACE, ANG II and AT1 receptors function as lung injury-promoting factors [26••, 55], whereas ACE2 protects against lung injury [26••] (Figure 2 ). These findings suggest that the beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers in lung injury models induced by bleomycin or irradiation, observed in the earlier studies, derive largely from their effects on the acute phase of those injuries.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the proposed role of the RAS in development of severe ARDS. In acute lung injury such as SARS-CoV infections, acid aspiration, pneumonias or sepsis, the generation of ANG II from ANG I is enhanced by ACE. ANG II contributes to acute lung failure through stimulation of the AT1 receptor, whereas ACE2 and the AT2 receptor negatively regulate this pathway and protect from acute lung failure. However, additional ACE2-regulated, but ANG II-independent, pathways seem to also contribute to ARDS.

ACE2 in SARS-mediated lung injury

Within a few months following the publication of the SARS-CoV genome [56, 57], ACE2 was identified as a potential receptor in cell line studies in vitro [28]. ACE2 has been demonstrated to bind SARS-CoV spike and to support ‘syncytia formation’, the fusion of spike-protein-expressing cells into large multinucleated cells that can also be seen in ‘real’ SARS infections. Using a mouse SARS infection model with ace2 knockout mice, our group provided evidence that ACE2 is indeed essential for SARS infections in vivo [27••]. When ace2 knockout mice are infected with the SARS coronavirus, they become resistant to virus infection [27••]. Virus titers from the lung tissues of infected ace2 knockout mice were 105-fold lower than those isolated from the lung of SARS-CoV-infected wild-type mice [27••]. The lung histology from ace2 knockout mice challenged with SARS coronavirus showed no signs of inflammation [27••], whereas some (but not all) SARS-infected wild-type mice displayed mild inflammation with leukocyte infiltration [27••, 58]. Thus, ACE2 is an essential receptor for SARS infections in vivo.

Despite many studies on SARS-CoV, the reasons why SARS-CoV infections trigger severe lung disease with such a high mortality, in contrast to other coronaviruses, remain a mystery. Accumulating evidence indicates that severe SARS infections are dependent upon the burden of viral replication as well as on the immunopathologic consequences of the host response (for review, see [59, 60]). In addition to the aberrant activation of immune systems, our own studies have implicated the involvement of the RAS in SARS pathogenesis: firstly, ACE2 is a critical SARS receptor in vivo; and secondly, ACE2 and other components of the RAS play a central role in controlling the severity of acute lung failure once the disease process has been initiated [27••] (Figure 2). Intriguingly, wild-type mice infected with SARS-CoV showed markedly downregulated ACE2 expression in lungs [27••]. Similarly, treatment with recombinant SARS-spike protein, in the absence of any other virus components, downregulates ACE2 expression in vitro and in vivo [27••]. Thus, SARS-CoV-infected or spike protein-treated wild-type mice resemble ace2 knockout mice, and, similar to ace2 mutant mice, spike-treated wild-type mice show markedly more severe pathology of acute lung injury. Additionally, in spike-treated mice, ANG II peptide levels were increased and the worsened ARDS symptoms could be partially reversed by AT1 receptor blocker treatment [27••]. By contrast, spike does not affect the ARDS symptoms in ace2 knockout mice [27••]. Thus, the downregulation of ACE2 expression in SARS-CoV infections might play a causal role in SARS pathogenesis, especially in disease progression to ARDS.

Conclusions and perspectives

ANG II plays roles in tissue remodeling and fibrotic changes through acting on fibroblasts or smooth muscle cells, thereby contributing to the pathogenesis or progression of pulmonary fibrosis or pulmonary hypertension. This notion is strongly supported by the successful treatment of these disease conditions using ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers in animal models. However, pilot clinical trials have failed to observe significant beneficial effects of ACE inhibitors on radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis or positive effects of AT1 receptor blockers on COPD-related pulmonary hypertension. Recently, the critical importance of the RAS in the pathogenesis of acute lung disease (i.e. ARDS/acute lung injury) has emerged. Hypothetically, the RAS appears to contribute to the initial severity of lung diseases rather than to later stages that define chronic fibrosis and tissue remodeling. In line with this notion, the D/D polymorphism of the ACE gene has been associated with the incidence of pneumonias in Japanese elderly patients [61] and mortality of ARDS patients [23, 24]. Importantly, ACE2 has been identified as a key SARS receptor, and ACE2 protects murine lungs from acute lung injury induced by acid aspiration, endotoxin shock, peritoneal sepsis or SARS spike challenge. These findings might provide the opportunity to develop ACE2 as a novel drug for ARDS that develops in emerging lung infectious diseases such as avian influenza A (H5N1) [62] or other diseases that affect lung function [63]. Because ACE2 is an non-specific protease, it would also be interesting to investigate the role of ACE2 and its metabolites, including angiotensin-(1–7), des-Arg(9)-bradykinin, apelin and dynorphin, in ARDS [14]. We look forward to the use of angiotensin system-modulating agents/molecules, in particular ACE2, as novel therapeutic agents to treat severe acute lung failure, a syndrome that currently affects millions of people without any effective drug treatment.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

We thank Chengyu Jiang, Shuan Rao and many others for their contributions. Supported by grants from The National Bank of Austria, The Austrian Ministry of Science and Education, IMBA, and EUGeneHeart to JMP. KK is supported by a Marie Curie Fellowship from the EU.

Contributor Information

Keiji Kuba, Email: Keiji.kuba@imba.oeaw.ac.at.

Josef M Penninger, Email: Josef.penninger@imba.oeaw.ac.at.

References

- 1.Ferrario C.M. The renin-angiotensin system: importance in physiology and pathology. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1990;15(Suppl 3):S1–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholls M.G., Richards A.M., Agarwal M. The importance of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease. J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:295–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skeggs L.T., Dorer F.E., Levine M., Lentz K.E., Kahn J.R. The biochemistry of the renin-angiotensin system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;130:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9173-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner A.J., Hooper N.M. The angiotensin-converting enzyme gene family: genomics and pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01994-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Studdy P.R., Lapworth R., Bird R. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and its clinical significance — a review. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:938–947. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.8.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavoie J.L., Sigmund C.D. Minireview: overview of the renin-angiotensin system–an endocrine and paracrine system. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2179–2183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orte C., Polak J.M., Haworth S.G., Yacoub M.H., Morrell N.W. Expression of pulmonary vascular angiotensin-converting enzyme in primary and secondary plexiform pulmonary hypertension. J Pathol. 2000;192:379–384. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH715>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrell N.W., Morris K.G., Stenmark K.R. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin II in development of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1186–H1194. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.4.H1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dezso B., Nielsen A.H., Poulsen K. Identification of renin in resident alveolar macrophages and monocytes: HPLC and immunohistochemical study. J Cell Sci. 1988;91:155–159. doi: 10.1242/jcs.91.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohkubo H., Nakayama K., Tanaka T., Nakanishi S. Tissue distribution of rat angiotensinogen mRNA and structural analysis of its heterogeneity. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakar S.S., Sellers J.C., Devor D.C., Musgrove L.C., Neill J.D. Angiotensin II type-1 receptor subtype cDNAs: differential tissue expression and hormonal regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;183:1090–1096. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donoghue M., Hsieh F., Baronas E., Godbout K., Gosselin M., Stagliano N., Donovan M., Woolf B., Robison K., Jeyaseelan R. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res. 2000;87:E1–E9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tipnis S.R., Hooper N.M., Hyde R., Karran E., Christie G., Turner A.J. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33238–33243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickers C., Hales P., Kaushik V., Dick L., Gavin J., Tang J., Godbout K., Parsons T., Baronas E., Hsieh F. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corvol P., Williams T.A., Soubrier F. Peptidyl dipeptidase A: angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:283–305. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krege J.H., John S.W., Langenbach L.L., Hodgin J.B., Hagaman J.R., Bachman E.S., Jennette J.C., O’Brien D.A., Smithies O. Male-female differences in fertility and blood pressure in ACE-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;375:146–148. doi: 10.1038/375146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crackower M.A., Sarao R., Oudit G.Y., Yagil C., Kozieradzki I., Scanga S.E., Oliveira-dos-Santos A.J., da Costa J., Zhang L., Pei Y. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peiris J.S., Yuen K.Y., Osterhaus A.D., Stohr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peiris J.S., Guan Y., Yuen K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat Med. 2004;10:S88–S97. doi: 10.1038/nm1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson L.D., Milberg J.A., Anardi D., Maunder R.J. Clinical risks for development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:293–301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware L.B., Matthay M.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raiden S., Nahmod K., Nahmod V., Semeniuk G., Pereira Y., Alvarez C., Giordano M., Geffner J.R. Nonpeptide antagonists of AT1 receptor for angiotensin II delay the onset of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:45–51. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.037382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall R.P., Webb S., Bellingan G.J., Montgomery H.E., Chaudhari B., McAnulty R.J., Humphries S.E., Hill M.R., Laurent G.J. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is associated with susceptibility and outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:646–650. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jerng JS, Yu CJ, Wang HC, Chen KY, Cheng SL, Yang PC: Polymorphism of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene affects the outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2006, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Hamming I., Timens W., Bulthuis M.L., Lely A.T., Navis G.J., van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Imai Y., Kuba K., Rao S., Huan Y., Guo F., Guan B., Yang P., Sarao R., Wada T., Leong-Poi H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first genetic demonstration of the critical involvement of the angiotensin system and ACE2 in early phase of pathogenesis of ARDS by using murine models of acute lung injury, mimicking ARDS patients in intensive care unit settings.

- 27••.Kuba K., Imai Y., Rao S., Gao H., Guo F., Guan B., Huan Y., Yang P., Zhang Y., Deng W. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first demonstration of ACE2 as a SARS-CoV receptor in vivo, and SARS-CoV spike-protein-mediated ACE2 downregulation followed by enhanced severity in acute lung injury.

- 28.Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffery T.K., Wanstall J.C. Pulmonary vascular remodeling: a target for therapeutic intervention in pulmonary hypertension. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;92:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandegar M., Fung Y.C., Huang W., Remillard C.V., Rubin L.J., Yuan J.X. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pulmonary vascular remodeling: role in the development of pulmonary hypertension. Microvasc Res. 2004;68:75–103. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrell N.W., Upton P.D., Kotecha S., Huntley A., Yacoub M.H., Polak J.M., Wharton J. Angiotensin II activates MAPK and stimulates growth of human pulmonary artery smooth muscle via AT1 receptors. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L440–L448. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.3.L440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuster D.P., Crouch E.C., Parks W.C., Johnson T., Botney M.D. Angiotensin converting enzyme expression in primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1087–1091. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassis L., Shenoy U., Lipke D., Baughn J., Fettinger M., Gillespie M. Lung angiotensin receptor binding characteristics during the development of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;54:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao L., al-Tubuly R., Sebkhi A., Owji A.A., Nunez D.J., Wilkins M.R. Angiotensin II receptor expression and inhibition in the chronically hypoxic rat lung. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1217–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chassagne C., Eddahibi S., Adamy C., Rideau D., Marotte F., Dubois-Rande J.L., Adnot S., Samuel J.L., Teiger E. Modulation of angiotensin II receptor expression during development and regression of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:323–332. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.3.3701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Suylen R.J., Wouters E.F., Pennings H.J., Cheriex E.C., van Pol P.E., Ambergen A.W., Vermelis A.M., Daemen M.J. The DD genotype of the angiotensin converting enzyme gene is negatively associated with right ventricular hypertrophy in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1791–1795. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9807060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanazawa H., Okamoto T., Hirata K., Yoshikawa J. Deletion polymorphisms in the angiotensin converting enzyme gene are associated with pulmonary hypertension evoked by exercise challenge in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1235–1238. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9909120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zakheim R.M., Mattioli L., Molteni A., Mullis K.B., Bartley J. Prevention of pulmonary vascular changes of chronic alveolar hypoxia by inhibition of angiotensin I-converting enzyme in the rat. Lab Invest. 1975;33:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nong Z., Stassen J.M., Moons L., Collen D., Janssens S. Inhibition of tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme with quinapril reduces hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling. Circulation. 1996;94:1941–1947. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molteni A., Ward W.F., Ts’ao C.H., Solliday N.H., Dunne M. Monocrotaline-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats: amelioration by captopril and penicillamine. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1985;180:112–120. doi: 10.3181/00379727-180-42151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Suylen R.J., Aartsen W.M., Smits J.F., Daemen M.J. Dissociation of pulmonary vascular remodeling and right ventricular pressure in tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme-deficient mice under conditions of chronic alveolar hypoxia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1241–1245. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2003144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pison C.M., Wolf J.E., Levy P.A., Dubois F., Brambilla C.G., Paramelle B. Effects of captopril combined with oxygen therapy at rest and on exercise in patients with chronic bronchitis and pulmonary hypertension. Respiration. 1991;58:9–14. doi: 10.1159/000195888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peacock A.J., Matthews A. Transpulmonary angiotensin II formation and pulmonary haemodynamics in stable hypoxic lung disease: the effect of captopril. Respir Med. 1992;86:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiely D.G., Cargill R.I., Wheeldon N.M., Coutie W.J., Lipworth B.J. Haemodynamic and endocrine effects of type 1 angiotensin II receptor blockade in patients with hypoxaemic cor pulmonale. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrell N.W., Higham M.A., Phillips P.G., Shakur B.H., Robinson P.J., Beddoes R.J. Pilot study of losartan for pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2005;6:88. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marshall R.P., McAnulty R.J., Laurent G.J. The pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis: is there a fibrosis gene? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:107–120. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuwano K., Hagimoto N., Hara N. Molecular mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis and current treatment. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:551–573. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song L., Wang D., Cui X., Shi Z., Yang H. Kinetic alterations of angiotensin-II and nitric oxide in radiation pulmonary fibrosis. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1998;17:141–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weber K.T. Fibrosis, a common pathway to organ failure: angiotensin II and tissue repair. Semin Nephrol. 1997;17:467–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang R., Ibarra-Sunga O., Verlinski L., Pick R., Uhal B.D. Abrogation of bleomycin-induced epithelial apoptosis and lung fibrosis by captopril or by a caspase inhibitor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L143–L151. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.1.L143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X., Rayford H., Uhal B.D. Essential roles for angiotensin receptor AT1a in bleomycin-induced apoptosis and lung fibrosis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2523–2530. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63607-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otsuka M., Takahashi H., Shiratori M., Chiba H., Abe S. Reduction of bleomycin induced lung fibrosis by candesartan cilexetil, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist. Thorax. 2004;59:31–38. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ward W.F., Sharplin J., Franko A.J., Hinz J.M. Radiation-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction and hydroxyproline accumulation in four strains of mice. Radiat Res. 1989;120:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L.W., Fu X.L., Clough R., Sibley G., Fan M., Bentel G.C., Marks L.B., Anscher M.S. Can angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors protect against symptomatic radiation pneumonitis? Radiat Res. 2000;153:405–410. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)153[0405:caceip]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mancini G.B., Khalil N. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker inhibits pulmonary injury. Clin Invest Med. 2005;28:118–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M.H. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marra M.A., Jones S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S., Khattra J., Asano J.K., Barber S.A., Chan S.Y. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hogan R.J., Gao G., Rowe T., Bell P., Flieder D., Paragas J., Kobinger G.P., Wivel N.A., Crystal R.G., Boyer J. Resolution of primary severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection requires Stat1. J Virol. 2004;78:11416–11421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11416-11421.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perlman S., Dandekar A.A. Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus infections: implications for SARS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:917–927. doi: 10.1038/nri1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lau Y.L., Peiris J.S. Pathogenesis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morimoto S., Okaishi K., Onishi M., Katsuya T., Yang J., Okuro M., Sakurai S., Onishi T., Ogihara T. Deletion allele of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene as a risk factor for pneumonia in elderly patients. Am J Med. 2002;112:89–94. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ungchusak K., Auewarakul P., Dowell S.F., Kitphati R., Auwanit W., Puthavathana P., Uiprasertkul M., Boonnak K., Pittayawonganon C., Cox N.J. Probable person-to-person transmission of avian influenza A (H5N1) N Engl J Med. 2005;352:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Geisbert T.W., Jahrling P.B. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nat Med. 2004;10:S110–S121. doi: 10.1038/nm1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]