Highlights

-

•

WU polyomavirus (WUPyV) was detected in 14 children with respiratory failure.

-

•

Of these children, eight had a perinatal disease and three were immunocompromised.

-

•

Multiplex PCR and culture were negative for other pathogens in five patients.

-

•

These five patients showed perihilar infiltrates after several days of symptoms.

-

•

WUPyV can be a pathogen in children with a history of perinatal disease.

Keywords: WU polyomavirus, Respiratory failure, Children, Preterm

Abstract

Background

WU polyomavirus (WUPyV) is a relatively new virus associated with respiratory infections. However, its role is unclear in children with severe respiratory failure.

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the characteristics of severe respiratory failure associated with WUPyV infection in children.

Study design

We retrospectively reviewed cases of respiratory tract infection at a tertiary children's hospital in Japan and performed real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for WUPyV using residual extracted nucleic acid samples taken from respiratory tract samples of pediatric patients primarily with respiratory failure. We investigated the clinical characteristics of patients positive for WUPyV and assessed samples positive for WUPyV for other respiratory pathogens using multiplex PCR.

Results

WUPyV was detected in 14 of 318 specimens of respiratory tract infections. The median age was 34 months and males were predominant (n = 11, 64%). An underlying disease was found in 11 (79%) patients including five preterm and three immunocompromised patients. The most common clinical diagnosis was pneumonia (n = 13, 93%). The majority of the samples were endotracheal tube aspirates (n = 11, 79%). Other viruses were co-detected in nine (64%) patients, while WUPyV was the only pathogen detected in five patients with a history of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. These five patients presented with fever and cough, and perihilar infiltrates were detected on chest radiograph in several days.

Conclusions

WUPyV was detected in children with severe respiratory failure independently or concurrently with other pathogens. WUPyV can be a pathogen for children with a history of preterm birth or an underlying disease.

1. Background

WU polyomavirus (WUPyV) is a relatively new human polyomavirus first detected in respiratory samples in 2007 [1]. It has since then been detected in respiratory tract samples in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients worldwide [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]]. However, its pathogenic role remains unclear, especially in pediatric patients with severe respiratory failure.

We had previously performed metagenomic shotgun sequencing for comprehensive detection of pathogens in selected patients without an etiological diagnosis and detected genomic fragments of WUPyV from a patient with respiratory failure. We therefore decided to undertake a retrospective study of WUPyV infection.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the characteristics of severe respiratory failure associated with WUPyV in children.

3. Study design

3.1. Study population

This retrospective study was conducted at the National Center for Child Health and Development, a pediatric tertiary care hospital in Tokyo, Japan. We identified pediatric patients (<18 years) with respiratory failure whose respiratory tract specimens were evaluated by PCR for respiratory pathogens between April 2010 and April 2017. Residual nucleic acid specimens were evaluated by real-time PCR for WUPyV according to established methods [8,9]. For patients whose specimen was positive for WUPyV, we extracted clinical information including age, sex, underlying disease, clinical course, and prognosis from the patients’ medical records.

3.2. Co-detection of other pathogens

Co-detection of other pathogens was evaluated in two steps. First, sputum culture and other nucleic acid testing performed as part of the clinical workup at the time of the episode of respiratory failure was reviewed. Coagulase negative Staphylococcus species and Neisseria species were considered not clinically significant and excluded. Second, multiplex real-time PCR using the Fast-track Diagnostics Respiratory Pathogens 21 (FTDRP21) multiplex assay kit (Fast-track Diagnostics, Luxembourg) was performed using the same residual samples that were used for WUPyV detection. The panel was able to detect 21 respiratory pathogens simultaneously including: influenza A, influenza A (H1N1) pdm09, influenza B, rhinovirus, coronavirus NL63, 229E, OC43, and HKU1, parainfluenza 1, 2, 3, and 4, human metapneumovirus A/B, bocavirus, respiratory syncytial virus A/B, adenovirus, enterovirus, parechovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and an internal control [10].

4. Results

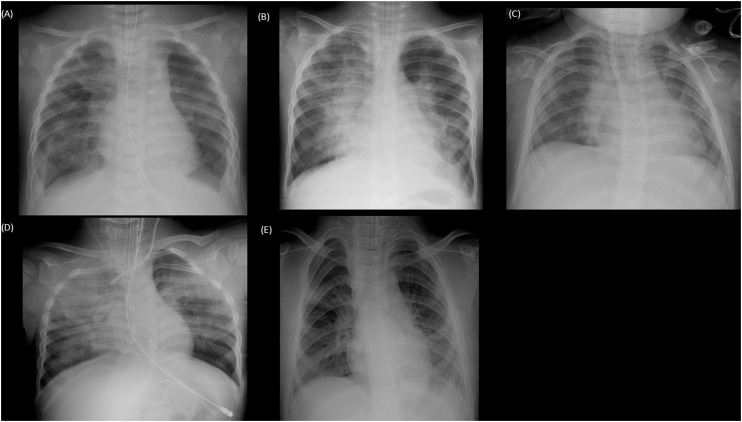

Three hundred eighteen samples were subjected to real-time PCR analysis. Among these, 14 (4.4%) samples were positive for WUPyV. The demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1 . The majority of the respiratory samples (n = 11, 79%) were taken from the lower respiratory tract. An underlying disease was found in 11 (79%) patients, including five preterm children and three immunocompromised patients. The details of the patients are shown in Table 2 . The sequences of WUPyV had been identified from sputum specimens by metagenomic analysis from one immunocompromised child with respiratory failure (Table 2, Patient 3, Supplementary Data 1). The patients were classified into four groups based on their underlying conditions: immunocompromised (Group 1), preterm (Group 2), other underlying diseases (Group 3) or previously healthy patients (Group 4). All cases with prematurity (Patients 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) and other underlying disorders (Patients 9, 10, 11) had a history of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Other viruses were co-detected in nine patients while only WUPyV was detected in five patients (Patients 5, 7, 9, 10, 11). Sputum cultures were evaluated in 11 patients, but clinically significant bacterial pathogens were not detected. All five patients in whom only WUPyV was detected had a history of admission to the NICU and presented with fever, cough, and respiratory distress and were intubated within one to six days after the onset of symptoms. The chest X-rays of the five patients are shown in Fig. 1 . Typical findings were apparent perihilar bilateral infiltration compatible with viral pneumonia.

Table 1.

The demographic, clinical data, and outcomes of patients with WU polyomavirus.

| Cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 14 | ||

| Age (months); median (range) | 34 (8-105) | |

| Sex: male | 10 | 71% |

| Underlying disease | 11 | 79% |

| Immunosuppressive status | 3 | 21% |

| Preterm | 5 | 36% |

| Other underlying diseases | 3 | 21% |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||

| Pneumonia | 13 | 93% |

| Bronchiolitis | 1 | 7% |

| Respiratory Samples | ||

| Endotracheal tube aspirates | 9 | 64% |

| Sputum | 2 | 14% |

| Nasopharyngeal swab | 3 | 21% |

| Detection of other pathogens | 9 | 64% |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 9 | 64% |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 2 | 14% |

| Death | 2 | 14% |

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical details and outcomes of 14 patients with WU polyomavirus.

| Pt | Group | Age (month) | Sex | Underlying Disease | Diagnosis | Intubation | ECMO | Samples | Co-detected organisms | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 32 | Male | Post liver transplant for fulminant hepatitis | Pneumonia | – | – | Upper | Rhinovirus | Alive |

| 2 | 1 | 36 | Male | Post liver transplant for fulminant hepatitis | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Rhinovirus | Alive |

| 3 | 1 | 51 | Male | Activated PI3 Kinase delta syndrome | Pneumonia | + | + | Lower | KI polyomavirus* | Dead |

| 4 | 2 | 6 | Male | Preterm (30 w, 1560 g) | Bronchiolitis | – | – | Upper | Human coronavirus NL63, Human Metapneumovirus | Alive |

| 5 | 2 | 8 | Female | Preterm (28 w, 683 g), 21 trisomy | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Negative | Alive |

| 6 | 2 | 19 | Female | Preterm (22 w, 335 g), chronic lung disease | Pneumonia | – | – | Upper | Adenovirus | Alive |

| 7 | 2 | 23 | Male | Preterm (26 w, 900 g) | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Negative | Alive |

| 8 | 2 | 41 | Female | Preterm (26 w, 435 g), chromosomal abnormality | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Respiratory syncytial virus | Dead |

| 9 | 3 | 12 | Male | Klinefelter syndrome (41 w, 2666 g) | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Negative | Alive |

| 10 | 3 | 54 | Male | Myelomeningocele (37 w, 1994 g) | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Negative | Alive |

| 11 | 3 | 105 | Male | Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (41 w, 4046 g) | Pneumonia | + | – | Lower | Negative | Alive |

| 12 | 4 | 15 | Female | – | Pneumonia | + | + | Lower | Human Metapneumovirus | Alive |

| 13 | 4 | 42 | Male | – | Pneumonia | – | – | Lower | Parainfluenza type 2, Adenovirus, Enterovirus | Alive |

| 14 | 4 | 79 | Male | – | Pneumonia | – | – | Lower | Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Alive |

Abbreviation: ECMO: Extra corporeal membrane oxygenation.

Detected by metagenomic analysis.

Fig. 1.

Radiograph findings of five patients with single detection of WU polyomavirus.

Radiograph (A)–(E), correspond to Patients 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, respectively. Apparent bilateral infiltration was seen in (A), (B), and (D); infiltration of the right hilar area was seen in (C); and infiltration of the right middle lung area and left lower lung area was seen in (E).

Regarding the severity and prognosis, two patients (Patients 3 and 12) required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and two patients (Patients 3 and 8) died. Although the respiratory condition of Patient 3 gradually improved, and ECMO was discontinued, multi-organ failure progressed and ultimately proved fatal. Patient 8, who had a chromosomal abnormality, died of respiratory failure and multi-organ failure.

5. Discussion

WUPyV was detected in 14 of 318 (4.4%) lower respiratory samples of children with severe respiratory failure. In five patients, WUPyV was the only detected pathogen despite the extended microbiological evaluation including bacterial cultures and multiplex real-time PCR.

The pathogenic role of WUPyV is still debated. Several reports revealed a similar detection rate from respiratory samples in children with or without respiratory symptoms [2,4,5]. In most previous reports, the samples were taken by nasopharyngeal swab, and the majority of the cases had no underlying condition. In our case series, the majority of WUPyV were detected from lower respiratory specimens, suggesting that WUPyV may cause lower respiratory infection.

In the current study, the majority of the patients had an underlying condition. Immunocompromised status was observed in three patients. WUPyV infections have been reported previously in immunocompromised patients. Siebrasse EA et al. reported an adult lung transplant recipient with Job syndrome and a pediatric bone marrow transplant recipient with fatal acute respiratory failure. In these cases, the WUPyV viral protein was detected by immunohistochemical staining of tissue from the respiratory tract, including lung tissue, which indicated the possibility of a pathogenic role for WUPyV in immunocompromised patients [11,12].

Apart from immunocompromised status, eight patients had a history of admission to the NICU. Of these patients, five were preterm patients. To our knowledge, no report has documented the association of prematurity or history of NICU admission with WUPyV infection. It is well known that prematurity is a risk factor for a number of respiratory virus infections, such as respiratory syncytial virus. Immature cell-mediated immunity and lung function (functional residual capacity, compliance, and resistance of the respiratory system) are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis [13,14]. A similar pathogenesis may also be at work in the lower respiratory tract of premature children with a WUPyV infection.

Other viruses were co-detected in nine of 14 (64%) patients. These viruses included respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, coronavirus, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, KI polyomavirus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Codetection of WUPyV with other respiratory viruses has often been reported in children and was consistent with the findings of our study [2,4,5]. It is still unknown if codetection of WUPyV with other viruses was associated with the severity of respiratory failure.

A major limitation of this study is the lack of histological evidence of WUPyV infection. The pathogenic role of WUPyV in respiratory failure remains unclear. Nonetheless, WUPyV alone was detected from the lower respiratory samples of several children with respiratory failure, and our findings add new insights into the clinical importance of WUPyV in children.

In conclusion, WUPyV was detected in children with severe respiratory failure. It can be pathogenic independently or concomitantly with other pathogens, especially in patients with a history of preterm birth or an underlying disease.

Author contribution

Uda contributed to conceptualizing and designing the study, drafted the manuscript, and performed the data analyses. Koyama-Wakai performed real-time PCR and revised the manuscript. Shoji contributed to revising the manuscript critically. Iwase, Motooka, and Nakamura performed the metagenomic analysis and contributed to revising the manuscript critically. Miyairi contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, revised the manuscript, and supervised the study as the corresponding author.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant fromNational Center for Child Health and Development (NCCHD 27-6 to Isao Miyairi).

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board at National Center for Child Health and Development (IRB-908, 1068).

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. J. R. Valera for his assistance in editing the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Presented in part: ID Week 2017 in San Diego, CA, USA on October 4–8, 2017.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2018.08.003.

Contributor Information

Kazuhiro Uda, Email: uda-ka@ncchd.go.jp.

Chitose Koyama-Wakai, Email: koyama-c@lisci.kitasato-u.ac.jp.

Kensuke Shoji, Email: shoji-k@ncchd.go.jp.

Noriyasu Iwase, Email: niwase@gen-info.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Daisuke Motooka, Email: daisukem@gen-info.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Shota Nakamura, Email: nshota@gen-info.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Isao Miyairi, Email: miyairi-i@ncchd.go.jp.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Gaynor A.M., Nissen M.D., Whiley D.M. Identification of a novel polyomavirus from patients with acute respiratory tract infections. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(5):e64. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han T.H., Chung J.Y., Koo J.W. WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13(11):1766–1768. doi: 10.3201/eid1311.070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin F., Zheng M., Li H. WU polyomavirus in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections. China J. Clin. Virol. 2008;42(1):94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wattier R.L., Vazquez M., Weibel C. Role of human polyomaviruses in respiratory tract disease in young children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14(11):1766–1768. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abed Y., Wang D., Boivin G. WU polyomavirus in children. Canada Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13(12):1939–1941. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao S., Lucero M.G., Nohynek H. WU and KI polyomavirus infections in Filipino children with lower respiratory tract disease. J. Clin. Virol. 2016;82:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada M., Hamada H., Sato-Maru H. WU polyomavirus detected in respiratory tract specimens from young children in Japan. Pediatr. Int. 2013;55(4):536–537. doi: 10.1111/ped.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teramoto S., Kaiho M., Takano Y. Detection of KI polyomavirus and WU polyomavirus DNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction in nasopharyngeal swabs and in normal lung and lung adenocarcinoma tissues. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011;55(7):525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2011.00346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bialasiewicz S., Whiley D.M., Lambert S.B. Development and evaluation of real-time PCR assays for the detection of the newly identified KI and WU polyomaviruses. J. Clin. Virol. 2007;40(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tscherne D.M., Garcia-Sastre A. Virulence determinants of pandemic influenza viruses. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121(1):6–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI44947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siebrasse E.A., Pastrana D.V., Nguyen N.L. WU polyomavirus in respiratory epithelial cells from lung transplant patient with Job syndrome. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21(1):103–106. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.140855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siebrasse E.A., Nguyen N.L., Willby M.J. Multiorgan WU polyomavirus infection in bone marrow transplant recipient. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22(1):24–31. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bont L., Kimpen J.L. Immunological mechanisms of severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(5):616–621. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drysdale S.B., Wilson T., Alcazar M. Lung function prior to viral lower respiratory tract infections in prematurely born infants. Thorax. 2011;66(6):468–473. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.148023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.