Highlights

-

•

Viral infections are commoner than bacterial infections in cystic fibrosis.

-

•

Rhinovirus is the most common respiratory pathogen in all seasons.

-

•

Multiplex PCR can effectively screen for respiratory viruses.

-

•

Viral infections should be considered in routine follow-up of cystic fibrosis.

-

•

The ratio of viral to bacterial infections decreases with age.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, Respiratory virus, Multiplex polymerase chain reaction, Pediatrics, Seasonality

Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis is a degenerative disease characterized by progressive epithelial secretory gland dysfunction associated with repeated respiratory infections. Bacterial infections are very frequent in children with cystic fibrosis, but because rapid

Methods

for screening for the wide variety of potentially involved viruses were unavailable until recently, the frequency of viral presence is unknown. Multiplex PCR enables screening for many viruses involved in respiratory infections.

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the frequency of viruses and bacteria in respiratory specimens from children with cystic fibrosis and to clarify the incidence and characteristics (seasonality and age of patients) of different viruses detected in children with cystic fibrosis.

Study design

In this 2-year prospective study, we obtained paired nasopharyngeal-swab and sputum specimens from children with cystic fibrosis during clinical respiratory examinations separated by at least 14 days. We analyzed viruses in nasopharyngeal-swab specimens with multiplex PCR and bacteria in sputum with standard methods.

Results

We analyzed 368 paired specimens from 33 children. We detected viruses in 154 (41.8%) and bacteria in 132 (35.9%). Bacteria were commoner in spring and summer; viruses were commoner in autumn and winter. In every season, Staphylococcus aureus was the commonest bacteria and rhinovirus was the commonest virus. Nearly all infections with Haemophilus influenzae occurred in autumn and winter.

Viruses were more prevalent in children <5 years old, and bacteria were more prevalent in children ≥12 years old.

Conclusions

Multiplex PCR screening for respiratory viruses is feasible in children with cystic fibrosis; the clinical implications of screening warrant further study.

1. Background

Cystic fibrosis is a degenerative disease characterized by progressive epithelial secretory gland dysfunction associated with repeated respiratory infections. The role of bacteria in cystic fibrosis is clear and widely studied [1]; however, the role of respiratory viruses in the progression of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis remains controversial. Viruses may be associated with significant clinical deterioration [2], [3] and may predispose to bacterial infection [4], [5]. Some viruses (e.g., influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus) are clearly associated with pulmonary exacerbations and worsening lung function in healthy children and in children with cystic fibrosis [6].

Before the advent of molecular detection methods, viral respiratory infections were diagnosed by antigen detection and virus isolation in cultures. However, the low sensitivity of antigen detection and the limitations of detecting only cultivable viruses made the prevalence of respiratory viruses in clinical specimens from children with cystic fibrosis remarkably low [7].

Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enables the detection of multiple respiratory viruses in a single reaction [8], [9]. This approach has clear clinical benefits as it helps physicians understand the etiology of clinical events and thus avoid prescribing antibiotics unnecessarily.

1.1. Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the frequency viruses and bacteria in respiratory specimens and to clarify the incidence and characteristics (seasonality and age of patients) of different viruses in children with cystic fibrosis.

1.2. Study design

From September 2012 through August 2014, we prospectively studied all children followed up periodically for cystic fibrosis in our hospital. Parents or legal guardians of all participants provided written informed consent and the institutional ethics committee approved the study.

We obtained paired nasopharyngeal-swab and sputum specimens from each patient during clinical respiratory controls separated by at least 14 days. Sputum was collected with the sputum induction method.

Viral DNA and RNA was extracted from nasopharyngeal swab samples with the QIAmp Viral mini Kit protocol (Qiagen®), amplified with specific primers with multiplex PCR (CLART® Pneumovir DNA array), and annealed to low-density arrays to detect 19 viruses simultaneously: adenovirus, bocavirus, coronavirus, Enterovirus (echovirus), influenza A (subtypes H3N2, pandemic H1N1, and seasonal H1N1), influenza B, influenza C, metapneumovirus (subtypes A and B), parainfluenza 1, parainfluenza 2, parainfluenza 3, parainfluenza 4 (subtypes A and B), rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. In the data analysis, we combined the subtypes to make the results clearer.

Sputum specimens were cultured with routine techniques in agar media (blood, MacConkey, Colistin nalidixic acid blood and chocolate agar), and isolates were identified at 48 h by Gram stain and biochemical tests.

All statistical analyses were done with SPSS v 19.

2. Results

A total of 368 paired upper airway samples were collected from 33 children (aged 10 months to 17 years; mean 7.43, median 8.0), yielding a mean of 11.2 samples per patient. Table 1 shows the results of the multiplex PCR. We detected viruses in 154 (41.8%) nasopharyngeal–swab specimens; the most common were rhinovirus (90/368; 24.4%), adenovirus (19/368; 5.2%), Enterovirus (15/368, 4.1%), and parainfluenza (11/368; 3%). Other viruses were detected in 29 specimens. Multiple viruses were detected in 20 samples (20/368; 5.4%); the most common virus–virus coinfection were rhinovirus plus adenovirus (6/20) and rhinovirus plus enterovirus (4/20).

Table 1.

Frequency of viruses detected.

| Multiplex PCR of nasopharyngeal swab specimens | n = 368 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 214 | 58.2 |

| Positive | 154 | 41.8 |

| Rhinovirus | 90 | 24.5 |

| Adenovirus | 19 | 5.2 |

| Enterovirus | 15 | 4.1 |

| Parainfluenza viruses | 11 | 3 |

| Influenza viruses | 9 | 2.4 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 5 | 1.4 |

| Metapneumovirus B | 3 | 0.8 |

| Bocavirus | 2 | 0.5 |

Table 2 shows the results of the cultures. We detected bacteria in 132 of the sputum specimens (132/368; 35.9%); the most frequently detected microorganisms were Staphylococcus aureus (102/368; 27.7%), Haemophilus influenzae (14/368; 3.8%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9/368; 2.4%). Other bacteria detected in less than 5 samples were Klebsiella oxytoca, Moraxella catarrhalis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Serratia marcescens.

Table 2.

Frequency of bacteria in sputum cultures.

| Sputum cultures | n (n = 368) |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Negative | 236 | 64.1 |

| Positive | 132 | 35.9 |

| S. aureus | 102 | 27.7 |

| H. influenzae | 14 | 3.8 |

| P. aeruginosa | 9 | 2.4 |

| E. cloacae | 3 | 0.8 |

| M. catarrhalis | 1 | 0.3 |

| K. oxytoca | 1 | 0.3 |

| S. marcescens | 2 | 0.5 |

We found 54 virus-bacteria coinfections (54/368; 14.7%); the most common combination was rhinovirus plus S. aureus (28/54) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Virus-bacteria coinfections in children with cystic fibrosis.

| Virus-bacteria coinfection (n) | n (n = 54) |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinovirus plus S. aureus | 28 | 51.9 |

| Enterovirus plus S. aureus | 7 | 13.0 |

| Rhinovirus plus H. influenzae | 3 | 5.6 |

| Parainfluenza viruses plus S. aureus | 3 | 5.6 |

| Rhinovirus plus P. aeruginosa | 2 | 3.7 |

| Adenovirus plus S. aureus | 2 | 3.7 |

| Others | 9 | 16.7 |

In general, viruses did not persist; the same virus was detected in three or more samples during two months’ follow-up in only 8/33 patients (4 rhinovirus and 2 adenovirus). By contrast, S. aureus was detected in subsequent sampling in 6/33 patients and persisted for more than 8 months in all but 1 patient, in whom it persisted for 2 months. No persistence of co-infections was observed.

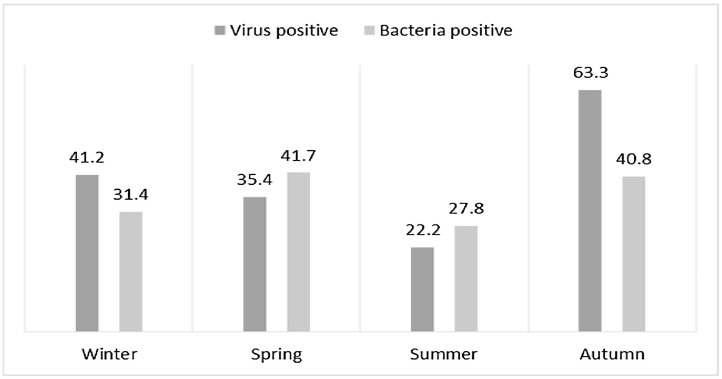

We also analyzed the seasonality of the respiratory infections detected. The highest prevalence of virus detection was in autumn (62/98; 63.2%), followed by winter (42/102; 41.2%); bacteria isolations were more common in spring (40/96; 41.7%) and autumn (40/98; 40.8%) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Seasonality of viral and bacterial infections. Observed frecuencies (%).

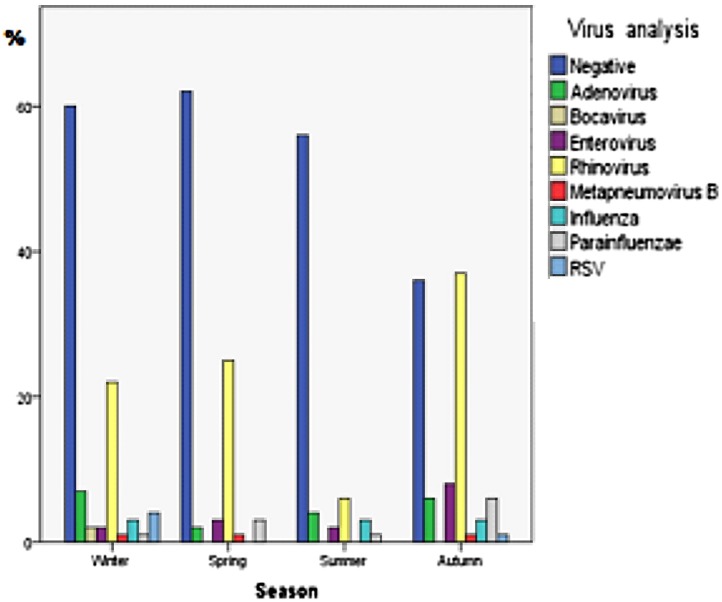

The viruses detected in all four seasons were very similar; rhinovirus was the most common in every season. Nearly all infections with H. influenzae occurred in autumn and winter (Fig. 2 ). The most common bacterial infection in all seasons was S. aureus.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of viruses detected in each season.

When we distributed patients into 5 age groups (<2 y, ≥2–<5 y, ≥5–<9 y, ≥9–<12 y, and ≥12 y), we found that the proportion of patients in whom viruses were detected decreased with age: 48.5% of samples were positive in children <2 years old, whereas only 31.4% of samples were positive in those ≥12 years old. By contrast, the proportion of infections due to bacteria was higher in patients >12 years old (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of samples positive for viruses and bacteria by age group.

3. Discussion

Until sensitive, specific, efficient molecular methods of nucleic acid detection were devised, the lack of techniques that could detect a wide variety of respiratory viruses in specimens made it difficult to know the prevalence of the different respiratory viruses in different groups of patients such as children with cystic fibrosis [9]. Multiplex PCR enabled us to screen for 19 viruses simultaneously in a single procedure on a single specimen. In our sample of 368 paired specimens, viral detection was more frequent than bacterial isolation (41.8% versus 35.9%), but the differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.06043, OR: 1.271 (IC95%: 0.9415–1.719)). There were more virus-bacteria coinfections (54/368) than virus–virus coinfections (20/368).

The most frequently identified virus in the 33 children with cystic fibrosis followed up for two years was rhinovirus (90/154 of positive samples). This is not surprising because rhinovirus is the most commonly detected virus in similarly aged pediatric populations when improved molecular techniques are used [10]. Rhinovirus increases the intensity of respiratory symptoms such as decreased appetite, muscle aches, headache, sore throat, increased sputum production, wheezing, and chest pain [7]. Other viruses such as adenovirus (19/154 of positive samples) or Enterovirus (15/154) can be found in the respiratory tracts of even asymptomatic children and can persist for months after respiratory infection [9], [10]. By contrast, other viruses detected in our study such as parainfluenza (11/154), influenza (9/154), respiratory syncytial virus (5/154), and metapneumovirus (3/154) are usually present only in symptomatic children and are very rare in healthy children [11], [12].

Whereas bacteria were detected more often in spring and summer, viruses were detected more often in autumn and winter. More than the half the viruses were detected in autumn (63.2%). We found scant information about the relative frequency of virus and bacterial infections in different seasons in children with cystic fibrosis.

The pathogens causing respiratory infections differed with the patients’ age. Viruses were detected in nearly half the samples in children up to 5 years old (48.5%–50%), and the rates of bacterial infection were clearly lower in this group (17.3%–21.2%). By contrast, in the group of children aged >12 years, viruses were only detected in 31.4%, and bacteria were detected in 68.6% of the samples. The statistical analysis reveals that viruses were more frequent than bacteria with significant differences in <5y group in contrast with ≥5y group (p < 0.05, OR: 2.71 (IC95%: 1.397–5.476)).

One limitation of the current study is the lack of clinical data, although our findings about the higher prevalence of viruses compared to bacteria could be useful in the study of the clinical implications. Another limitation is that we analyzed nasopharyngeal swab specimens rather than bronchoalveolar lavage specimens, where the detection of the viruses might be more clinically useful; however, nasopharyngeal swabs have the definite advantage that they are noninvasive and easy to obtain in routine clinical practice.

Respiratory specimens from children with cystic fibrosis are routinely screened for bacteria. Viruses could be involved in pulmonary exacerbations and could increase the morbidity of bacteria. Our study shows that routine screening for viruses is also feasible and recommendable, especially in children younger than 4 years old. Multiplex PCR methods are available in clinical laboratories and allow relatively quick screening for a wide variety of respiratory viruses in a single procedure on a single sample.

Conflicts of interest

All authors no reported conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Abbot Laboratories generously provided the reagents for the analyses; however, they had no role in the study design, in the collecting or analysis of data, in elaborating the manuscript or in the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- 1.Ratjen F., Doring G. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2003;361(9358):681–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12567-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Almeida M.B., Zerbinati R.M., Tateno A.F. Rhinovirus C and respiratory exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16(6):996–999. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.100063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Da Silva Filho L.V., Zerbinati R.M., Tateno A.F. The differential clinical impact of human coronavirus species in children with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;206(3):384–388. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singanayagam A., Joshi P.V., Mallia P. Virus exacerbating chronic pulmonary disease: the role of immune modulation. BMC Med. 2012;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifton I.J., Kastelik J.A., Peckham D.G. Ten years of viral and non-bacterial serology in adults with cystic fibrosis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2008;136:128–134. doi: 10.1017/S0950268807008278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong D., Grimwood K., Carlin J.B. Severe viral respiratory infections in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 1998;26(6):371–379. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199812)26:6<371::aid-ppul1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns J.L., Emerson J., Kuypers J. Respiratory viruses in children with cystic fibrosis: viral detection and clinical findings. Influenzae Other Respir. Viruses. 2012;6(3):218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frobert E., Escuret V., Javouhey E. Respiratory viruses in children admitted to hospital intensive care units: evaluating the CLART® Pneumovir DNA array. J. Med. Virol. 2011;83(1):150–155. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krause J.C., Panning M., Hengel H. The role of multiplex PCR in respiratory tract infections in children. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2014;111(38):639–645. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jartti T., Söderlund-Venermo M., Hedman K. New molecular virus detection methods and their clinical value in lower respiratory tract infections in children. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2013;14(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Zalm M.M., Wolfs T.F. Prevalence and impact of respiratory viral infections in young children with cystic fibrosis: prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1171–1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortiz J.R., Neuzil K.M., Victor J.C. Influenzae-associated cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. Chest. 2010;137(4):852–860. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]