Abstract

Preeclampsia may arise in some women from insufficient or defective decidualization before and during early pregnancy that, in turn, disrupts decidual immune cell populations and activity, thereby compromising placental formation and/or function. The transcriptomics of choriodecidua (chorionic villous samples) and cultured endometrial stromal cells decidualized in vitro derived from mid-secretory biopsies of women who experienced severe preeclampsia overlapped significantly with the transcriptomics of mid-secretory biopsies from women with recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent miscarriage (RM) and endometriosis. This finding gave rise to the hypothesis of “endometrium spectrum disorders”, in which RIF, RM, normotensive intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia and preterm birth may all lie on a continuum of decidual dysregulation, whereby phenotypic expression is based on the specific molecular pathways that are disrupted and the severity of disruption. Finally, women who conceived using artificial (programmed) IVF protocols had widespread dysregulation of cardiovascular function in the first trimester and were at increased risk for several adverse pregnancy outcomes including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia. These IVF protocols preclude the development of a corpus luteum, which is a key regulator of endometrial function. Therefore, the lack of circulating CL product(s) (e.g., relaxin, a potent vasodilator and stimulus of decidualization) could adversely impact the maternal cardiovascular system directly and/or compromise decidualization, thereby increasing the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia.

Keywords: decidua, trophoblast, preeclampsia, endometrium spectrum disorders, in vitro fertilization, autologous frozen embryo transfer, relaxin

Introduction

Adverse pregnancy outcomes may have antecedents in the pre- and peri-conception periods, and first trimester of pregnancy. This idea was supported by studies implicating dysregulation of endometrial maturation (decidualization) during the secretory phase and early pregnancy in the genesis of preeclampsia1–4. The concept of “endometrium spectrum disorders” then emerged3, which was underpinned by the integration of multiple endometrial transcriptomic databases available in the public domain5. These bioinformatics analyses provided evidence for dysregulation of molecular pathways in common among the classic endometrial disorders—recurrent implantation failure, recurrent miscarriage, endometriosis—and one of the great obstetrical or placental syndromes, preeclampsia5,6. Conceivably, other adverse pregnancy outcomes that may arise from placental pathology including normotensive intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birth, also fall within the continuum of endometrial spectrum disorders affecting implantation, placentation or both depending upon the specific molecular pathways disrupted and the severity of disruption3. Although the genesis of the great obstetrical syndromes including preeclampsia is likely to be multifactorial, in some women these disease entities may have antecedents in endometrial dysregulation during early pregnancy or even before pregnancy.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) is another setting in which pre- and peri-conception, as well as early pregnancy factors may impact obstetrical outcome. In pregnancies conceived by IVF using artificial (programmed) cycles involving hypothalamic-pituitary suppression and development of the endometrium with estradiol and progesterone, a corpus luteum (CL) does not develop7. These IVF protocols were observed to perturb endometrial gene expression in the mid-secretory phase8,9, and to be associated with greater risk of post-term delivery, large for gestation age infants and macrosomia, as well as placental accreta10,11. In addition, artificial cycles were also linked to maternal hemodynamic dysregulation in the first trimester, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia12,13. Because the CL is a key regulator of endometrial function including decidualization in the secretory phase and early pregnancy, one potential explanation for increased incidence of these adverse obstetrical outcomes is that, despite luteal support with exogenous estradiol and progesterone, the absence of other crucial circulating CL factors(s) negatively affects endometrial maturation in artificial IVF cycles7,10,12. Another potential, albeit not mutually exclusive explanation is that the dosage and timing of estradiol and progesterone administration for luteal support is suboptimal8,9.

In this review, the molecular evidence of impaired decidualization in preeclampsia, and the emerging concept of “endometrial spectrum disorders”, in which dysregulated decidualization of preeclampsia, recurrent implantation failure, recurrent miscarriage and endometriosis demonstrated significant overlap of molecular pathology will be presented. In addition, the discovery of dysregulated maternal hemodynamics during the first trimester of artificial (programmed) IVF cycles, as well as the association with increased risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia will be also be presented in the context of the corpus luteum, or more precisely, the lack thereof, in the case of artificial cycles.

Endometrium Spectrum Disorders: A New and Emerging Concept

Molecular Evidence of Impaired Endometrial Maturation in Preeclampsia

One widely held theory is that preeclampsia originates within the placental bed during early gestation in many women. Normally, the fetal extravillous trophoblast emanating from the anchoring villous tips invade the gestational endometrium (decidua) and inner 1/3 of the myometrium, remodeling the uterine spiral arteries from low caliber, high resistance to high caliber, low resistance blood vessels. These physiological changes of the spiral arteries facilitate increased maternal blood flow into the intervillous space. In contrast, preeclampsia is often associated with impaired trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling, thereby restricting blood flow into the intervillous space leading to placental ischemia. These placentation deficiencies may not be unique to preeclampsia, as they have also been described, albeit not universally so, in late sporadic miscarriage, normotensive fetal growth restriction, placental abruption, and preterm labor6.

It should be noted that the classical view of the biological consequences of spiral artery remodeling or lack thereof, as presented above, has been recently called into question. Revised computational modeling suggested that spiral artery remodeling is unlikely to contribute substantially to reducing uterine vascular resistance and increasing blood flow in normal pregnancy, rather the (proximal) radial artery is a more significant resistance site14. Computational modeling further revealed that spiral artery remodeling in normal pregnancy reduces the velocity of increased blood flow into the intervillous space, thereby protecting delicate villi from mechanical damage and increasing the transit time of blood flow through the intervillous space allowing for adequate exchange of oxygen and nutrients across the syncytiotrophoblast layer15. According to this model, failure of spiral artery remodeling in preeclampsia would lead to the opposite chain of events, i.e., mechanical damage of villi by high velocity blood flow and rapid transit time of blood flow through the intervillous space precluding adequate oxygen and nutrient exchange across the syncytiotrophoblast layer15. Nevertheless, regardless of which model is apropos, each predicts that failure to remodel spiral arteries would impair placental function. In both scenarios, ischemia-reperfusion injury would also occur as a consequence of spontaneous and hormone-induced constriction or relaxation of spiral arteries that were not remodeled and retained vascular smooth muscle.

Because uterine invasion and spiral artery remodeling by trophoblast can be deficient in preeclampsia, this fetal cell has been intensively investigated. Moreover, the paternal genetic contribution to disease etiology could be manifest, at least in part, through impairment of trophoblast invasion. The seminal work of Fisher and colleagues revealed the extensive molecular and functional aberrations of the extravillous trophoblast in early onset, severe preeclampsia as investigated at the end of pregnancy in situ, and after trophoblast isolation, in vitro16. However, a potential caveat to this methodological approach is that molecular pathology at the end of pregnancy may be more related to the phenotypic expression of the disease, which typically emerges at that time or may even be a consequence of the disease (e.g., sFLT1 could conceivably be injurious to endometrium, in addition to endothelium). Therefore, the molecular pathology of tissues procured at delivery is likely to be unrelated to the molecular etiology which caused the disease months before, when the physiological processes of uterine trophoblast invasion and spiral arterial remodeling transpired. That is, the large temporal gap between the acquisition of placental tissues for molecular studies at delivery and the critical period of trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling occurring in early pregnancy, may preclude any insights into the molecular genesis of preeclampsia. One potential solution to this conundrum is prospective acquisition of early placental tissues (surplus chorionic villous samples or CVS) months before onset of clinical manifestations. Although the advent of noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPs) has markedly reduced the number of CVS procedures performed world-wide, collaboration among large medical centers with the greatest volume of CVS cases annually, could lead to acquisition of sufficient sample numbers for molecular and functional investigation of preeclampsia etiology targeting the trophoblast.

Another potentially relevant tissue that has received little attention in the context of adverse pregnancy outcomes is the maternal decidua (“soil”), which extravillous trophoblast (“seed”) invade (vide supra). Conceivably, insufficient or defective endometrial maturation (decidualization) that begins in the secretory phase and continues after implantation may impede trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling, thereby contributing to the genesis of preeclampsia1,17. This alternative, but not mutually exclusive hypothesis is perhaps intuitive or self-evident, in light of the close apposition of endometrial stromal, glandular epithelial and maternal immune cells with trophoblast and spiral arteries in the placental bed. Furthermore, the maternal inheritance pattern of preeclampsia could be manifest, at least in part, through dysregulation of decidualization. Normally, massive molecular and functional changes occur in endometrial stromal and epithelial cells, spiral arteries and immune cells during decidualization in the secretory phase and early pregnancy. Implantation and placentation depend on the optimal and timely progression of decidualization. Decidualization of the glandular epithelium is prerequisite to histiotrophic nutrition during early gestation prior to onset of maternal blood flow; uterine [natural killer] NK cells become the major immune cell type in the placental bed and assume an immunomodulatory rather than cytotoxic phenotype, and they initiate spiral artery remodeling and stimulate trophoblast invasion; uterine macrophages accumulate and they adopt an “M2” or alternatively active rather than pro-inflammatory phenotype; and T regulatory cells contribute to immune tolerance at the maternal-fetal interface in the face of the fetoplacental semi-allograft3,18. In essence, decidualization is preparation of the “soil” for the “seed”, i.e., embryo implantation and subsequent placentation. Impairment of this process as one possible etiology of preeclampsia would seem to be a reasonable hypothesis to explore.

In order to investigate relevant reproductive tissue temporally related to decidualization, trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling, we prospectively obtained surplus CVS at ~11.5 gestational weeks in women who developed preeclampsia with severe features (sPE) or who experienced normal pregnancy (NP) outcome 5–6 months later1. These tissue samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and ultimately analyzed by DNA microarray. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not detect a molecular signature consistent with ischemia or ischemia-reperfusion, rather many genes identified as biomarkers of decidualization were downregulated in the CVS from women who developed sPE relative to NP outcome including insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), glycodelin or progesterone-associated endometrial protein (PAEP), prolactin (PRL) and IL-15. These initial observations prompted a wider text mining approach, which revealed many other dysregulated decidual genes that, in turn, provided the justification for a formal bioinformatics reanalysis of the raw data from our CVS microarray data2.

The bioinformatics reanalysis of the CVS microarray data revealed 396 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between CVS from sPE and NP-CVS, of which 154 or 40% overlapped with DEGs changing during endometrial maturation either in the secretory phase or early pregnancy (p=4.7 × 10−14), the latter DEGs obtained by reanalyzing publically available microarray datasets of normal decidualization. Moreover, approximately 73% of these 154 DEGs changed in the opposite direction compared to normal endometrial maturation (p=0.01), and 75% overlapped significantly with DEGs between proliferative vs late secretory endometrium or DEGs between decidualized vs nondecidualized endometrium obtained from tubal ectopic pregnancies (p=4.4 × 10−9). Neither of these endometrial tissues contain extravillous trophoblast, thus suggesting a primary role for dysregulated decidualization. Moreover, 16 DEGs normally upregulated in uterine compared to peripheral NK cells were downregulated in sPE- compared to NP-CVS (p<0.0001). DEGs normally upregulated in uterine relative to peripheral macrophages were downregulated in sPE- vs NP-CVS (p=9.5 × 10−3) and vice versa (p=1.1 × 10−6)3. Taken together, these observations suggested deficient or defective endometrial maturation including uterine NK cells and macrophages may precede the development of preeclampsia with severe features. The concept that dysregulated decidualization is involved in the genesis of preeclampsia was supported by 6 studies published throughout the last 10 years or so, which demonstrated a reduction of circulating concentrations of IGFBP1 during early pregnancy in women who later developed PE (reviewed in3).

Another notable finding from the CVS microarray study was that the average mRNA expression of a cohort of 20 decidual genes uniquely upregulated in normal late secretory compared to proliferative endometrium were downregulated in sPE- vs NP-CVS by ~ 2-fold (p<0.0001)2. This observation suggested that the dysregulation of endometrial maturation in the women who developed PE with severe features may have started before pregnancy during the secretory phase. Indeed, the idea that endometrial pathology may reside in the secretory endometrium was strongly reinforced by Garrido-Gomez and coworkers, who reported marked impairment of in vitro decidualization of endometrial stromal cells isolated and then cultured from mid-secretory endometrial biopsies of women who experienced sPE during the previous 1–5 years4. In fact, there was significant overlap of DEGs that arose from sPE-CVS vs NP-CVS as reported by Rabaglino and colleagues with the DEGs observed by Garrido-Gomez and coworkers in cultured endometrial stromal cells decidualized in vitro that were derived from women who experienced prior sPE vs normal pregnancy5.

A priori, decidual tissue at delivery is likely to be markedly dissimilar from decidual tissue in the secretory phase or early pregnancy (vide supra). This important point was highlighted by additional bioinformatics analysis of differential gene expression in these temporally disconnected decidual tissues from women who experienced sPE vs NP, insofar as there was little or no overlap5. Thus, designing strategies to address the molecular genesis of PE which resides in the secretory endometrium and/or placental bed of early pregnancy based upon the molecular pathology of delivered tissue may be misleading, and unlikely to lead to preventative or early corrective measures.

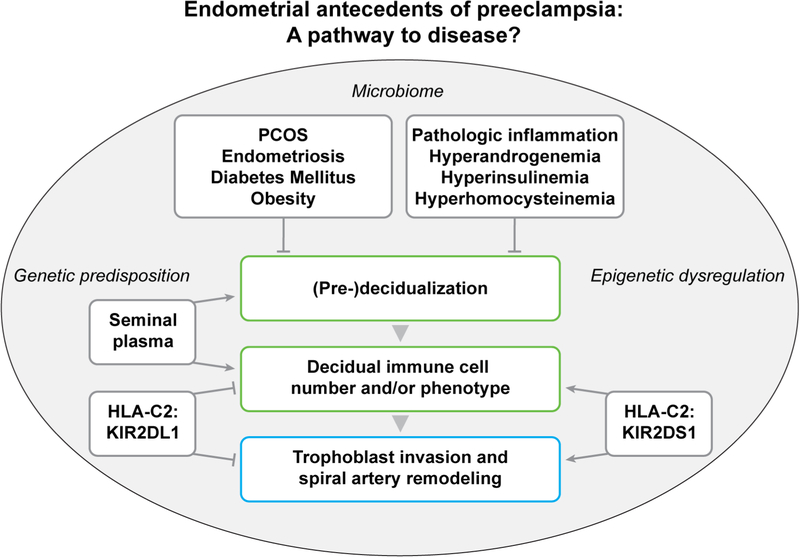

In summary, emerging evidence supports the concept that preeclampsia may arise at least in some women from dysregulated decidualization including aberrant endometrial immune cell number and/or function in the secretory phase and during early pregnancy1,2,4 (Fig. 1). In delivered placentas, decidual function is also perturbed, which may contribute to or arise from deleterious circulating placental factors like sFLT1 (e.g.19, and reviewed in3). But, as discussed above, the transcriptomics of delivered decidua are distinct from those of early pregnancy or the secretory phase in women who developed preeclampsia, and as such, may not be relevant to disease etiology3,5. Perhaps not totally unexpected in light of this potential link between aberrant decidualization and preeclampsia, an elegant recently published study provided evidence that intrauterine growth restriction, another disease entity classified under the great obstetrical or placental syndromes, may also have origins in impaired decidualization20.

Figure 1. Aberrant decidualization in the late secretory phase and during early pregnancy may play a role in the development of preeclampsia for some women.

From Conrad KP, Rabaglino MB, Post Uiterweer ED. Emerging role for dysregulated decidualization in the genesis of preeclampsia. Placenta 2017;60:125; with permission.

Evidence for Common Molecular Pathways of Dysregulated Endometrial Maturation in Preeclampsia, Recurrent Implantation Failure, Recurrent Miscarriage and Endometriosis

Because dysregulated decidualization was associated with preeclampsia, we asked the question whether there might be molecular overlap with other endometrial disorders5. To this end, we reanalyzed 8 microarray databases in the public domain from normal and pathologic endometrium or decidua. A significant proportion of the DEGs up- or downregulated in CVS from women who experienced PE with severe features compared to NP, or in cultured endometrial stromal cells decidualized in vitro derived from mid-secretory biopsies of women who experienced severe PE relative to NP (vide supra), demonstrated overlap with, and the same directional change as DEGs in recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent miscarriage (RM) and endometriosis (OSIS) compared to their respective control tissues5.

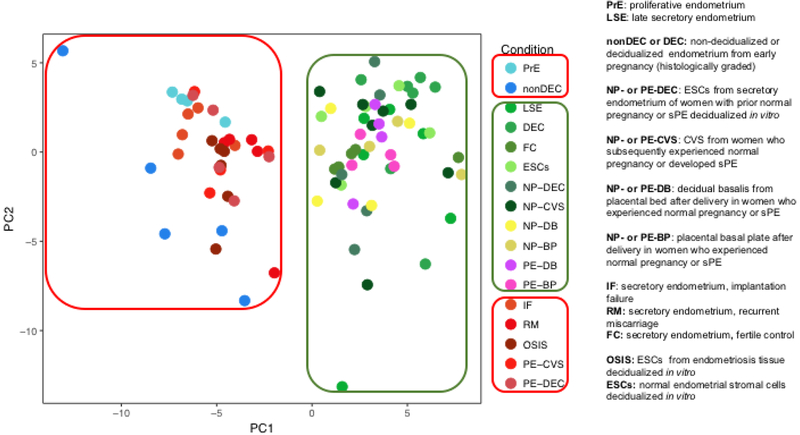

In order to further explore this idea, a functional analysis and pathway-driven approach was taken5. The cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway (264 genes) was one of the most prominent and significant molecular pathways in common among normal and pathological endometrium. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to compare gene expression in this pathway among the different normal and pathological endometrial tissues represented by 8 microarray databases (Fig. 2). CVS and in vitro decidualized endometrial stromal cells derived from mid-secretory phase biopsies of women who suffered sPE segregated with the three endometrial disorders. In contrast, decidua procured at delivery from women affected by sPE clustered with normal endometrium, indicating that the expression pattern of the genes of these tissues at least in the cytokine-cytokine receptor pathway more resembled the normal than pathological endometrium. Of course, this does imply that other molecular pathways in the decidua obtained at delivery from women who suffered sPE may not be abnormal. Overall, however, the differentially expressed genes affected in delivered tissues were not overlapping with those found in the CVS or in vitro decidualized endometrial stromal cells from mid-secretory phase biopsies of women who suffered sPE. In the same vein, proliferative endometrium and non-decidualized early pregnancy endometrium as histologically assessed, clustered with pathological endometrium in the context of the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway.

Figure 2. Principal component analysis of genes belonging to the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway.

Principal component plots show that normal endometrial samples obtained from healthy women (shades of green, n=36), decidual tissues obtained post-delivery from women with preeclampsia (shades of pink, n=8) and normal pregnancies (shades of yellow n=8) formed a distinct cluster. Endometrial samples from women with pathologic endometrium (shades of red, n=25) and samples from non-decidualized endometrium (nonDEC) or proliferative endometrium (PrE; shades of blue, n=9) formed another distinct cluster. The analysis was applied to 264 genes belonging to the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway.

LSE: late-secretory endometrium. DEC: ~9 week gestational endometrium with confluent decidualization. FC: mid-secretory endometrium from fertile controls. ESCs: endometrial stromal cells isolated from mid-secretory biopsies of healthy women, cultured, and decidualized in vitro. PE-and NP-CVS: chorionic villous samples obtained from women ~11.5 gestational weeks who developed preeclampsia with severe features or experienced normal pregnancy. PE- and NP-DEC: mid-secretory endometrial biopsies obtained from women between 1 and 5 years after a pregnancy either complicated by PE with severe features or an uncomplicated pregnancy. Endometrial stromal cells were subsequently isolated, cultured and decidualized in-vitro. PE-and NP-DB: decidual tissue obtained by placental bed biopsy after cesarean section. PE- and NP-BP: decidual tissue harvested from the basal plate of delivered placentas. IF: secretory endometrium from women with recurrent implantation failure. RM: secretory endometrium from women with recurrent miscarriage. OSIS: endometrial stromal cells isolated from ovarian endometriomas, cultured and decidualized in vitro.

From Rabaglino MB, Conrad KP. Evidence for shared molecular pathways of dysregulated decidualization in preeclampsia and endometrial disorders revealed by microarray data integration. FASEB J. 2019 Nov;33(11):11682–11695; with permission.

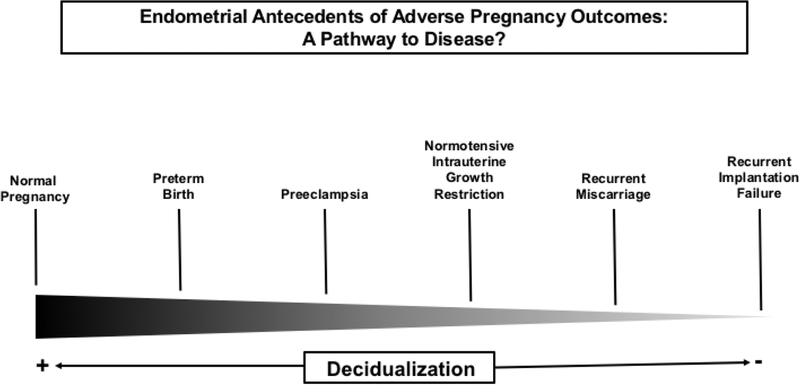

Taken together, integration of multiple microarray datasets derived from normal and pathologic endometrium suggested that, at least in some women, preeclampsia may be part of a continuum of endometrial disorders involving varying degrees of molecular dysregulation affecting implantation, placentation or both. Indeed, other disease entities classified as placental syndromes may also fall along this continuum (Fig. 3). That PE has, in common with the classical endometrial disorders, many differentially expressed genes and gene pathways strengthens the concept that the genesis of the disease may reside in the decidua at least for some women. Viewing PE in this light may also partly explain why women with endometriosis who become pregnant experience increased PE risk as reported by some, but not all investigators. Similarly, recurrent miscarriage was also associated with increased PE risk (see5 for citations).

Figure 3. Endometrium spectrum disorders.

A significant number of differentially expressed genes that were either up- or downregulated in chorionic villous samples from women who experienced preeclampsia with severe features compared to normal pregnancy demonstrated overlap with, and the same directional change as differentially expressed genes in recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent miscarriage (RM) and endometriosis (OSIS) relative to their respective control tissues. Similarly, a significant number of differentially expressed genes that were either up- or downregulated in cultured endometrial stromal cells decidualized in vitro derived from mid-secretory biopsies of women who experienced severe preeclampsia compared to normal pregnancy demonstrated overlap with, and the same directional change as differentially expressed genes in recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent miscarriage (RM) and endometriosis (OSIS) compared to their respective control tissues. These findings gave rise to the notion of endometrium spectrum disorders, in which disease phenotype may be determined in part by which endometrial molecular pathways are disrupted and the severity of the disruption.

In Vitro Fertilization: Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Preeclampsia

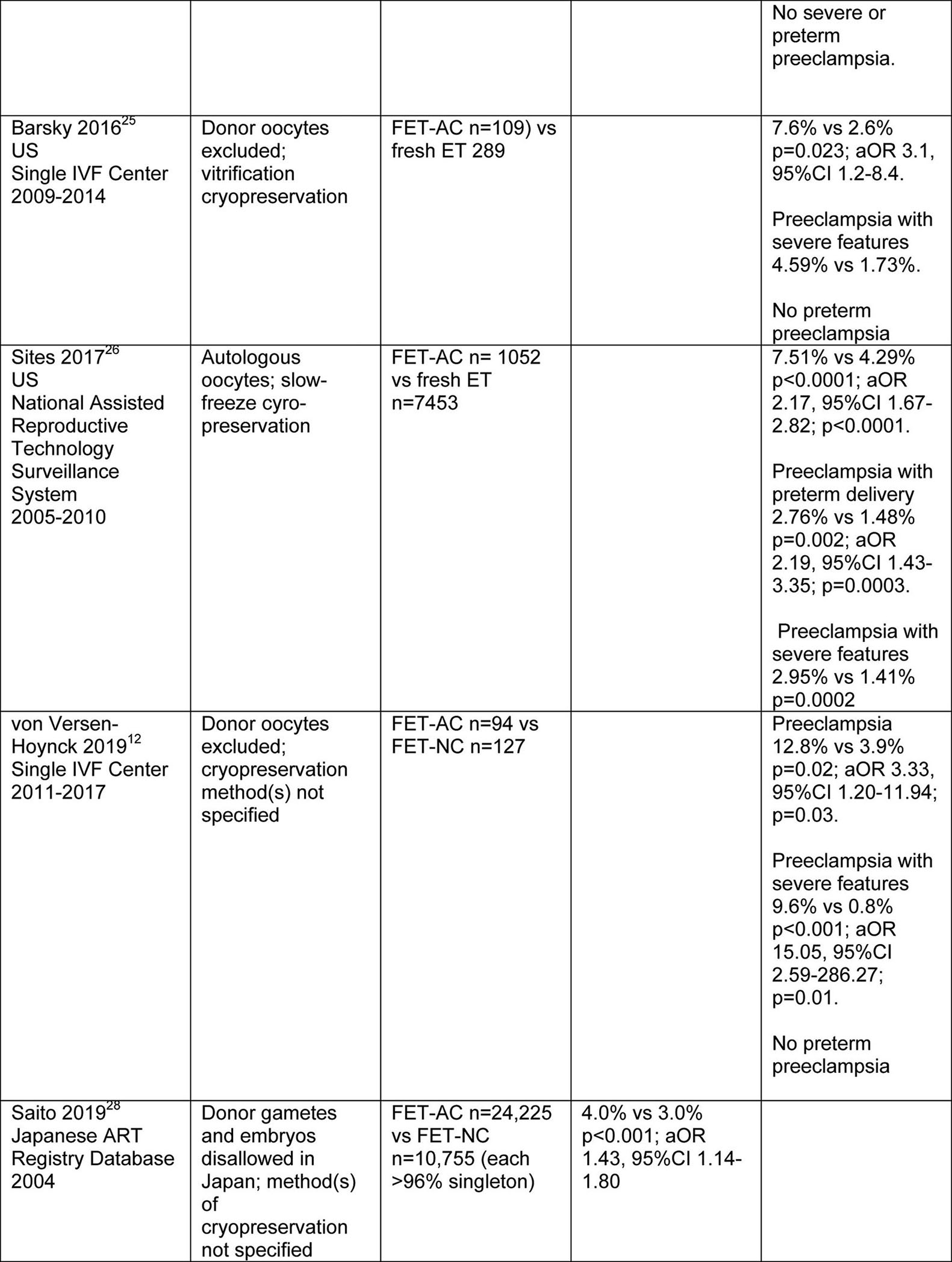

An association between IVF and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia has been thoroughly documented (Tables 1–3). Several groups of researchers reported increased frequency of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia in frozen embryo transfer (FET) vs fresh ET. However, the FET protocol(s) were not delineated, and whether donor gametes were included or not was only specified in one of the studies21–23. In the investigation by Opdahl and colleagues, relative risk (RR) for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy was 7.0% and 4.7%, respectively, for FET and spontaneous pregnancy, aOR 1.41, 95%CI 1.27–1.56 (adjusted for maternal age, parity, birth year, infant sex and country). The same authors also noted higher risk in siblings conceived by FET vs fresh ET, aOR 2.39, 95%CI 1.48–3.8623. More recently, the risk of preeclampsia was also found to be increased for autologous FET in artificial cycles (AC) vs fresh ET24–26. In one of these studies, patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) were randomized to FET-AC or fresh ET cycles24. Finally, in another investigation, autologous FET-NC and FET-stimulated cycles were employed, and the authors observed no significant differences in the rate of hypertensive disorders among women conceiving by FET-NC, FET-stimulated cycle, fresh ET or spontaneous conception27. Taken together, these studies suggested that FET, and in particular FET-AC protocols may be associated with increased rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia as compiled from Table 1 and summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Singleton Live Births from Frozen Embryo Transfer (FET) versus Fresh ET

|

|

|

IVF + intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) combined except where noted.

ART, assisted reproductive technology; BC, blastocyst; NS, nonsignificant.

Singletons + twins combined.

Reference: 268,599 single spontaneously conceived pregnancies (1.00), RR 4.7%.

Reference: fresh cycles (1.00).

Table 3.

Incidence of preeclampsia (%) according to IVF protocol

| Publication | IVF Protocols or Spontaneous Conception | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen Embryo Transfer-Artificial Cycles | Frozen Embryo Transfer-Natural Cycles | Fresh Embryo Transfer | Spontaneous Conception | |

| Sazonova 201244 | 5.6a | 4.5 | 2.8 | |

| Chen 201624 | 4.4 | 1.4 | ||

| Barsky 201625 | 7.6 | 2.6 | ||

| Sites 201726 | 7.5 | 4.3 | ||

| von Versen-Höynck 201912 | 12.8 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 4.9 |

| Ernstad 201910 | 8.2 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 2.8 |

| Mean ± SEM (%) | 7.7 ± 1.2 | 4.2 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.7 |

FET protocols not specified.

Deletion of Sazonova 2012 yielded a similar mean ± SEM: 8.1 ± 1.4.

Table 2.

Incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (%) according to IVF protocol

| Publication | IVF Protocols or Spontaneous Conception | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frozen Embryo Transfer-Artificial Cycles | Frozen Embryo Transfer-Natural Cycles | Fresh Embryo Transfer | Spontaneous Conception | |

| Wennerholm 199727 | 7.2a | 7.7 | 6.2 | |

| Wikland 201021b | 11.8b | 5.5 | ||

| Ishihara 201422c | 2.8c | 1.8 | ||

| Opdahl 201523c | 7.0c | 5.7 | 4.7 | |

| Saito 201928 | 4.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Ginstrom Ernstad 201910 | 10.5 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 3.9 |

| Mean ± SEM (%) | 7.2 ± 1.8% | 5.4 ± 1.3% | 5.2 ± 1.0% | 4.9 ± 0.7% |

, 82% FET-NC.

Combination of FET-AC and −NC.

Presumably mostly FET-AC, although FET protocols not specified.

Omitting FET-AC for Wikland 2010, Ishihara 2014, and Opdahl 2015 due to uncertain status of FET protocol, yielded a similar mean : 7.3%.

In a recently published prospective study, we recruited women during early pregnancy with singleton intrauterine pregnancies who conceived using autologous oocytes and delivered live born infants (n=878)12. No participants had an infertility diagnosis of premature ovarian failure or were recipients of donor oocytes or embryos. After adjustment for several preeclampsia risk factors (i.e., maternal age, nulliparity, history of hypertension, BMI, PCOS, pre-gestational and gestational diabetes), women conceiving by FET in artificial cycles, in which a CL did not develop, had increased risk for preeclampsia (aOR 2.73, 95%CI 1.14–6.49) and preeclampsia with severe features (aOR 6.45, 95%CI 1.94–25.09) compared to sub-fertile women with one CL. In a sub-analysis of FET in artificial cycles compared to FET in modified natural cycles with one CL, the adjusted odds ratios were 3.55, 95%CI 1.20–11.94 for developing preeclampsia, and 15.05, 95%CI 2.59–286.27 for preeclampsia with severe features. Importantly, women conceiving by fresh ET in ovarian stimulation cycles who had multiple CL did not show increased preeclampsia risk. This study was the first to evaluate preeclampsia risk in IVF from the standpoint of CL status. The findings implicated absence of the CL as a possible contributor to the development of preeclampsia (Tables 1 and 3).

In a parallel study, we serially evaluated cardiovascular function in women before, during and after pregnancies, who conceived after controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) (>1 CL), autologous FET or fresh donor oocyte-derived embryos transferred in artificial cycles (0 CL), or spontaneous conceptions (1 CL)12,13. We observed significant attenuation of the gestational changes in numerous cardiovascular parameters during the first trimester in women who conceived by IVF without a CL, which mostly recovered during the second trimester. These findings were consistent with the hypothesis that circulating CL factor(s) mediate cardiovascular adaptations to pregnancy during the first trimester in spontaneous pregnancy, and placental factors supersede after the corpus luteal-placental shift7. The cardiovascular adaptations to pregnancy in the IVF participants with multiple CL were comparable to those observed in spontaneous pregnancies. Although we established an association between absent CL, dysregulated cardiovascular adaptations in the first trimester, and increased preeclampsia risk, whether these factors were causally linked remains to be proven.

A recent comprehensive publication from Sweden based on a retrospective registry study of singleton pregnancies after autologous FET reported a frequency of 8.2% for preeclampsia in artificial cycles (0 CL; n=1446) compared to 4.4% in natural cycles (1 CL; n=6297)—aOR 1.78, 95%CI 1.43–2.21 (adjusted for maternal age, BMI, parity, year of birth of infant, maternal smoking, chronic hypertension, child’s sex, level of maternal education, and years of involuntary childlessness)10. The women conceiving by fresh ET with multiple CL (n=24,365) showed a lower rate of preeclampsia closer to that of spontaneous conceptions (n=1,127,566)—3.7% and 2.8%, respectively. Similar trends were observed for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.10 Additional published studies demonstrated that women conceiving by autologous FET in artificial cycles had increased risk for hypertensive disease of pregnancy or preeclampsia compared to autologous FET in natural cycles, or fresh ET in ovarian stimulation cycles. However, a potential etiologic role for absent CL in the elevated risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia in artificial cycles was not hypothesized in these reports (e.g.,24–26,28; Tables 1–3).

In summary, although not yet confirmed by a rigorous randomized controlled clinical trial comparing autologous FET-AC and FET-NC or modified NC, the emerging data suggest that use of IVF protocols which lead to suppression of CL formation may increase preeclampsia risk. These data are concerning due to the immediate- and long-term detrimental consequences of preeclampsia for both mother and child. Thus, in addition to pre-pregnancy maternal characteristics in many IVF patients such as older maternal age and subfertility, absence of the CL as an etiological factor in the impaired maternal cardiovascular adaptations during early pregnancy and increased preeclampsia risk should also be considered. The absence of critical circulating CL factor(s) is perhaps the most likely explanation for the dysregulation of maternal cardiovascular function observed during early pregnancy in women conceiving by IVF without a CL, in part because either full or partial recovery subsequently transpired after the “corpus luteal-placental shift” coincident with secretion of placental factors12,13. But, whether the absence of CL factor(s) and of their vasodilatory and pro-decidualizing attributes, or the possibility of suboptimal luteal support with estrogen and progesterone for endometrial preparation in artificial cycles (dose and/or timing—vide supra)5,8, or both underlie increased preeclampsia risk is less clear. Ultimately, if replacement of the missing CL factor(s) (e.g., relaxin) restores maternal cardiovascular function in early pregnancy and reduces preeclampsia risk, then this approach might be an alternative preventative strategy to autologous FET in a natural cycle for some women, and perhaps the only approach available for women who have ovarian failure requiring donor oocytes or embryos to conceive. Mild ovarian stimulation, which would permit CL development in a FET cycle, might be used is women who do not ovulate on a regular basis.

The absence of a CL and circulating CL product(s) likely contribute to the increased risk of preeclampsia in autologous FET-AC vs FET-NC. However, whether or not cryopreservation, in addition to absence of a CL, may confer added risk of preeclampsia in FET-AC compared to fresh ET is difficult to test. Close examination of the study by Sites et al. in the context of CL status may shed some light on this question26. Autologous fresh embryo transfer (>1 CL) and autologous frozen embryo transfer in an artificial cycle (0 CL) yielded rates of PE of 4.29 and 7.51%, respectively (Tables 1 and 3). The difference could have been a consequence of embryo state (fresh vs frozen) and/or CL number (>1 vs 0 CL). Donor fresh and frozen embryo transfer in artificial cycles (0 CL) yielded rates of preeclampsia of 12.13 and 10.78%, respectively26 (use of artificial cycles for donor frozen embryo transfers was standard of care according to Dr. Sites, personal communication). These preeclampsia rates were not significantly different, which suggested that the freeze/thaw manipulation of embryos did not confer increased risk for PE (although a ceiling effect cannot be excluded). Comparing autologous (4.29%) and donor fresh (12.13%) ET revealed that the difference, 7.17%, was PE risk attributable to “donor” (vs autologous) and “CL” (>1 vs 0 CL) effects. Comparing autologous (7.51%) and donor frozen (10.78%) ET both using artificial cycles (0 CL) revealed that the difference, 4.62%, was the contribution to PE attributable to “donor” (vs autologous) effect, alone. Thus, the difference between the PE rates attributable to “donor” and “CL” effects (7.17%) and “donor” (4.62%) effect, 2.55%, must be due to the “CL” effect, alone. Although any conclusion based on these rough estimates must be regarded cautiously, the artificial cycle (0 CL), in addition to a donor embryo source appeared to account for the considerably higher rates of preeclampsia in women who were recipient of donor-oocyte derived embryos.

Why is IVF Associated with Increased Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes?

Artificial (Programmed) Cycles

The emerging evidence suggests that perhaps not all IVF protocols are created equal with respect to increased risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia. Although IVF protocols were frequently not presented in sufficient detail in many of the publications, after close inspection of those in which they were delineated, the balance of evidence implicated the artificial (or programmed) cycle protocol. That is, elevated risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia primarily resulted from FET-AC, not FET-NC or FET-stimulated, or fresh ET cycles (Table 1). Perhaps not coincidentally, the maternal hemodynamic adaptations to pregnancy were perturbed in AC, but not COS cycle protocols12,13. Close inspection of the grand averages of the rates for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia listed in Table 1 further highlight that increased risk is associated with the artificial cycle (Tables 2 and 3).

In most of the studies that reported increased risk for preeclampsia in autologous FET-AC protocols, the gestational age of preeclampsia onset and the severity of disease were not specified (Table 1). However, a few did provide these details. Chen and coworkers observed increased risk for term, but not preterm preeclampsia or preeclampsia with severe features24; increased frequency of term preeclampsia and preeclampsia with severe features, but not preterm preeclampsia were noted by both von Versen-Hoynck et al.12 and Barsky and colleagues25; and Sites and coworkers reported increased incidence of both preterm and term preeclampsia, and preeclampsia with severe features in autologous FET-AC26. Although the number of studies are too few to draw any definite conclusions, with the exception of Sites and coworkers, term preeclampsia both with and without severe features was associated with autologous FET-AC protocols. A recent theory for the pathogenesis of term preeclampsia proposes that it arises from villous overcrowding, which leads to compression of intervillous spaces that, in turn, impedes blood flow causing placental ischemia. That is, villous growth outstrips uterine capacity29 (vide supra).

Interestingly, women with low circulating relaxin concentration in early pregnancy were observed to be at increased risk of developing late onset preeclampsia (≥34 weeks)30. Possibly, the vasodilatory attributes of relaxin are important in some women to mitigate the physiological rise in circulating vasoconstrictors such as sFLT1, thereby restraining the normal restoration of the maternal circulation to the non-pregnant state of relative vasoconstriction towards the end of pregnancy13,31,32. In fact, circulating sFLT1 and the sFLT1/PLGF ratio were significantly higher at the end of pregnancy in women conceiving by IVF especially for AC (0 CL) protocols33, perhaps reflecting villous overcrowding and placental ischemia. Whereas circulating relaxin is absent in artificial cycles, concentrations are either comparable to spontaneous pregnancy or markedly higher in controlled ovarian stimulation cycles, the latter possibly explaining the equivalent rates of preeclampsia in COS and spontaneous pregnancies as noted above (Tables 1 and 3).

The finding by Sites et al. of increased preterm, in addition to term preeclampsia after autologous FET-AC protocol should not be ignored (vide supra)26. Indeed, this investigation may have identified increased risk for both term and preterm PE due to larger cohort sizes, and hence, increased study power. However, on the surface, it is difficult to reconcile preterm and term PE based on a common decidual etiology. Preterm preeclampsia is widely believed to be associated with impaired trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodeling, while recent theory suggests that term preeclampsia does not involve deficient placentation, but rather villous overcrowding (vide supra). Conceivably, villous overcrowding might be exacerbated by post-term delivery and larger placentas associated with large for gestational age or macrosomic infants—adverse pregnancy outcomes also associated with artificial (programmed) IVF cycles (e.g.,10,34). Indeed, post-term delivery itself has been associated with increased preeclampsia and eclampsia risk35 presumably as a consequence of the mechanisms outlined above being exacerbated by prolonged time for placental growth29. Enhanced frequency of LGA and macrosomia in autologous FET during artificial cycles are also consistent with the increased risk of term preeclampsia, insofar as it is not infrequently accompanied by a large for gestational age (LGA) fetus36,37 and large placenta38. Whether term preeclampsia may be associated with excessive trophoblast invasion, albeit to lesser degree than accreta spectrum disorders that also occur more frequently in artificial IVF cycles (e.g.,11), is not known.

On the one hand, excessive trophoblast invasion is observed in tubal pregnancy and accreta spectrum disorders, in which decidua is deficient and/or dysregulated39–41. On the other, dysregulated decidualization is associated with preterm preeclampsia with severe features, in which trophoblast invasion is deficient2–4 (vide supra). These apparently disparate actions of the decidua on trophoblast invasion are difficult to reconcile mechanistically, i.e., how can decidual pathology lead to both excessive and deficient trophoblast invasion? One potential explanation is that activation of different molecular pathways account for these divergent actions of the decidua on trophoblast behavior that may be regulated, at least in part, by factors derived from the corpus luteum, or lack thereof. A priori, it seems logical to presume that decidual pathology would not be restricted to one phenotypic expression of excessive trophoblast invasion as in some cases of placental accreta disorders, but rather different molecular pathology could also arise, which leads to impaired trophoblast invasion frequently observed in preterm preeclampsia.

Future Investigations

In light of the association between dysregulated decidualization and preeclampsia, the underlying molecular mechanism(s) of the pathologic decidua now need to be identified, in order to design prophylactic or corrective interventions. Eventually, efforts to improve decidualization before and during early pregnancy might be indicated in those women at increased risk for the disease (e.g., by administration of hormones known to promote decidualization). Finally, circulating or urinary biomarkers or a panel of biomarkers reflecting endometrial dysfunction might be helpful in identifying women at increased risk (e.g., low circulating IGFBP-1 or glycodelin before and/or during early pregnancy)3.

Given the perturbed maternal physiology and increased risk of several adverse pregnancy outcomes in IVF cycles involving autologous frozen embryo transfer in artificial (programmed) cycles, what can be done to intervene? Careful inspection of the data revealed that the increased risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia was not observed in frozen embryo transfer using natural or stimulated cycles, or controlled ovarian stimulation cycles. Based on this revelation, it is reasonable to propose that a large multi-site, randomized clinical trial be conducted comparing pregnancy outcomes between autologous FET-AC and FET-NC, FET-modified NC, or FET-stimulated cycles12. In a subgroup of patients, maternal physiology could be intensively investigated, in order to determine whether it would be normal after FET-NC, FET-modified NC or FET-stimulated cycles in contrast to FET-AC as predicted7,12,13,42. If a RCT confirms the hypothesis that maternal physiology and pregnancy outcome will be improved, then FET-NC, FET-modified NC or FET-stimulated cycles might be preferred protocols in many women. A common denominator is the absence of a corpus luteum in artificial IVF cycles, whereas at least one CL develops in FET-NC, FET-modified NC and FET-stimulated cycles7,12,13. All CL product(s) are missing in FET-AC (except for E2 and P4 administered for luteal support), and therefore, the absence of any one or several of them could underlie the dysregulated maternal cardiovascular adaptations to pregnancy and increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Indeed, both the cardiovascular system and endometrium are known targets of at least one CL factor that is not replaced in AC protocols, relaxin (vide supra;42,43). Therefore, including the missing CL factor(s) like relaxin with E2 and P4 for luteal support in artificial cycles might be investigated, in order to determine whether the addition of CL factor(s) like relaxin to the IVF medical regimen would correct the dysregulated maternal cardiovascular physiology and reduce the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. For women with ovarian failure for which natural IVF cycles are unattainable, replacing the missing CL factor(s) may be the only option.

Key Points:

Preeclampsia may arise in some women from insufficient or defective decidualization before and during early pregnancy that, in turn, disrupts decidual immune cell populations and activity, thereby compromising placental formation and/or function.

The transcriptomics of choriodecidua (chorionic villous samples) and cultured endometrial stromal cells decidualized in vitro derived from mid-secretory biopsies of women who experienced severe preeclampsia overlapped significantly with the transcriptomics of mid-secretory biopsies from women with recurrent implantation failure (RIF), recurrent miscarriage (RM) and endometriosis.

Women who conceived using artificial (programmed) IVF protocols had widespread dysregulation of cardiovascular function in the first trimester and were at increased risk for several adverse pregnancy outcomes including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia. These IVF protocols preclude the development of a corpus luteum, which is a key regulator of endometrial function.

The lack of circulating CL product(s) (e.g., relaxin, a potent vasodilator and stimulus of decidualization) could adversely impact the maternal cardiovascular system directly and/or compromise decidualization, thereby increasing the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by P01 HD065647-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the J. Robert and Mary Cade Professorship of Physiology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Dr. Conrad discloses use patents for relaxin.

References

- 1.Founds SA, Conley YP, Lyons-Weiler JF, Jeyabalan A, Hogge WA, Conrad KP. Altered global gene expression in first trimester placentas of women destined to develop preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30(1):15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabaglino MB, Post Uiterweer ED, Jeyabalan A, Hogge WA, Conrad KP. Bioinformatics approach reveals evidence for impaired endometrial maturation before and during early pregnancy in women who developed preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad KP, Rabaglino MB, Post Uiterweer ED. Emerging role for dysregulated decidualization in the genesis of preeclampsia. Placenta. 2017;60:119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrido-Gomez T, Dominguez F, Quinonero A, et al. Defective decidualization during and after severe preeclampsia reveals a possible maternal contribution to the etiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E8468–E8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabaglino MB, Conrad KP. Evidence for shared molecular pathways of dysregulated decidualization in preeclampsia and endometrial disorders revealed by microarray data integration. FASEB J. 2019:fj201900662R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The “Great Obstetrical Syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3):193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad KP, Baker VL. Corpus luteal contribution to maternal pregnancy physiology and outcomes in assisted reproductive technologies. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304(2):R69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altmae S, Tamm-Rosenstein K, Esteban FJ, et al. Endometrial transcriptome analysis indicates superiority of natural over artificial cycles in recurrent implantation failure patients undergoing frozen embryo transfer. Reproductive biomedicine online. 2016;32(6):597–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young SL, Savaris RF, Lessey BA, et al. Effect of randomized serum progesterone concentration on secretory endometrial histologic development and gene expression. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(9):1903–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ginstrom Ernstad E, Wennerholm UB, Khatibi A, Petzold M, Bergh C. Neonatal and maternal outcome after frozen embryo transfer: Increased risks in programmed cycles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):126 e121–126 e118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaser DJ, Melamed A, Bormann CL, et al. Cryopreserved embryo transfer is an independent risk factor for placenta accreta. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(5):1176–1184 e1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Versen-Höynck F, Schaub AM, Chi YY, et al. Increased Preeclampsia Risk and Reduced Aortic Compliance With In Vitro Fertilization Cycles in the Absence of a Corpus Luteum. Hypertension. 2019;73(3):640–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conrad KP, Petersen JW, Chi YY, et al. Maternal Cardiovascular Dysregulation During Early Pregnancy After In Vitro Fertilization Cycles in the Absence of a Corpus Luteum. Hypertension. 2019;74(3):705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark AR, James JL, Stevenson GN, Collins SL. Understanding abnormal uterine artery Doppler waveforms: A novel computational model to explore potential causes within the utero-placental vasculature. Placenta. 2018;66:74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta. 2009;30(6):473–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher SJ. Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4 Suppl):S115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brosens JJ, Pijnenborg R, Brosens IA. The myometrial junctional zone spiral arteries in normal and abnormal pregnancies: a review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1416–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gellersen B, Brosens IA, Brosens JJ. Decidualization of the human endometrium: mechanisms, functions, and clinical perspectives. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(6):445–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deepak V, Sahu MB, Yu J, et al. Retinoic Acid Is a Negative Regulator of sFLT1 Expression in Decidual Stromal Cells, and Its Levels Are Reduced in Preeclamptic Decidua. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):1104–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunk C, Kwan M, Hazan A, et al. Failure of Decidualization and Maternal Immune Tolerance Underlies Uterovascular Resistance in Intra Uterine Growth Restriction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wikland M, Hardarson T, Hillensjo T, et al. Obstetric outcomes after transfer of vitrified blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(7):1699–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishihara O, Araki R, Kuwahara A, Itakura A, Saito H, Adamson GD. Impact of frozen-thawed single-blastocyst transfer on maternal and neonatal outcome: an analysis of 277,042 single-embryo transfer cycles from 2008 to 2010 in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(1):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opdahl S, Henningsen AA, Tiitinen A, et al. Risk of hypertensive disorders in pregnancies following assisted reproductive technology: a cohort study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(7):1724–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen ZJ, Shi Y, Sun Y, et al. Fresh versus Frozen Embryos for Infertility in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barsky M, St Marie P, Rahil T, Markenson GR, Sites CK. Are perinatal outcomes affected by blastocyst vitrification and warming? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):603 e601–603 e605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sites CK, Wilson D, Barsky M, et al. Embryo cryopreservation and preeclampsia risk. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(5):784–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennerholm UB, Hamberger L, Nilsson L, Wennergren M, Wikland M, Bergh C. Obstetric and perinatal outcome of children conceived from cryopreserved embryos. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(8):1819–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito K, Kuwahara A, Ishikawa T, et al. Endometrial preparation methods for frozen-thawed embryo transfer are associated with altered risks of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, placenta accreta, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Hum Reprod. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redman CW, Sargent IL, Staff AC. IFPA Senior Award Lecture: making sense of preeclampsia - two placental causes of preeclampsia? Placenta. 2014;35 Suppl:S20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeyabalan A, Stewart DR, McGonigal SC, Powers RW, Conrad KP. Low relaxin concentrations in the first trimester are associated with increased risk of developing preeclampsia [abstract]. Reproductive Sci. 2009;16(3):101A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Versen-Hoynck F, Strauch NK, Liu J, et al. Effect of Mode of Conception on Maternal Serum Relaxin, Creatinine, and Sodium Concentrations in an Infertile Population. Reprod Sci. 2019;26(3):412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, et al. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(7):672–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conrad KP, Graham GM, Chi YY, et al. Potential Influence of the Corpus Luteum on Circulating Reproductive and Volume Regulatory Hormones, Angiogenic and Immunoregulatory Factors in Pregnant Women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choux C, Ginod P, Barberet J, et al. Placental volume and other first-trimester outcomes: are there differences between fresh embryo transfer, frozen-thawed embryo transfer and natural conception? Reproductive biomedicine online. 2019;38(4):538–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caughey AB, Stotland NE, Escobar GJ. What is the best measure of maternal complications of term pregnancy: ongoing pregnancies or pregnancies delivered? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1047–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong X, Demianczuk NN, Buekens P, Saunders LD. Association of preeclampsia with high birth weight for age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(1):148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong X, Demianczuk NN, Saunders LD, Wang FL, Fraser WD. Impact of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension on birth weight by gestational age. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(3):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahlstrom B, Romundstad P, Oian P, Vatten LJ, Eskild A. Placenta weight in preeclampsia. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2008;87(6):608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jauniaux E, Collins S, Burton GJ. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randall S, Buckley CH, Fox H. Placentation in the fallopian tube. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1987;6(2):132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sliz A, Locker KCS, Lampe K, et al. Gab3 is required for IL-2- and IL-15-induced NK cell expansion and limits trophoblast invasion during pregnancy. Sci Immunol. 2019;4(38). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conrad KP. Maternal vasodilation in pregnancy: the emerging role of relaxin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301(2):R267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conrad KP. G-Protein-coupled receptors as potential drug candidates in preeclampsia: targeting the relaxin/insulin-like family peptide receptor 1 for treatment and prevention. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(5):647–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sazonova A, Kallen K, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Wennerholm UB, Bergh C. Obstetric outcome in singletons after in vitro fertilization with cryopreserved/thawed embryos. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1343–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]