Abstract

Background

Brassica is a very important genus of Brassicaceae, including many important oils, vegetables, forage crops, and ornamental horticultural plants. TLP family genes play important regulatory roles in the growth and development of plants. Therefore, this study used a bioinformatics approach to conduct the systematic comparative genomics analysis of TLP gene family in B. napus and other three important Brassicaceae crops.

Results

Here, we identified a total of 29 TLP genes from B. napus genome, and they distributed on 16 chromosomes of B. napus. The evolutionary relationship showed that these genes could be divided into six groups from Group A to F. We found that the gene corresponding to Arabidopsis thaliana AT1G43640 was completely lost in B. rapa, B. oleracea and B. napus after whole genome triplication. The gene corresponding to AT1G25280 was retained in all the three species we analysed, belonging to 1:3:6 ratios. Our analyses suggested that there was a selective loss of some genes that might be redundant after genome duplication. This study proposed that the TLP genes in B. napus did not directly expansion compared with its diploid parents B. rapa, and B. oleracea. Instead, an indirect expansion of TLP gene family occurred in its two diploid parents. In addition, the study further utilized RNA-seq to detect the expression pattern of TLP genes between different tissues and two subgenomes.

Conclusions

This study systematically conducted the comparative analyses of TLP gene family in B. napus, discussed the loss and expansion of genes after genome duplication. It provided rich gene resources for exploring the molecular mechanism of TLP gene family. Meanwhile, it provided guidance and reference for the research of other gene families in B. napus.

Keywords: TLP gene family, Polyploid, Orthologous and paralogous, Gene duplication and loss, Expression analysis, B. napus

Background

B. napus belonged to the Brassica genus, which included many important oils, vegetables crops and ornamental horticultural plants. The allotetraploids B. napus (Brassica napus; AACC, 2n = 38) was obtained by crossing of the two diploid basic species of B. rapa (Brassica rapa; AA, 2n = 20), and B. oleracea (Brassica oleracea; CC, 2n = 18) [1–3]. B. napus was not only one of the world’s four major oil crops, but also one of the most important oil crops in China. Currently, the genomes of these species have been sequenced and the datasets have been released [2, 4–6]. Recently, several important achievements and progress in comparative genomics and functional genomics research have been achieved, which reflected the importance and practicality of these data [7–9]. Therefore, we could use bioinformatics to dig deeper into these public data. Until now, the TLP gene family of B. napus has not been reported at the genome level.

The Tubby-like proteins (TLP) family was a smaller gene family in animals, it played very important role in animal growth and development [10, 11]. The Tubby gene was first isolated by positional cloning in obese mice, subsequently, other members of TLP gene family were successively identified [10, 12]. Studies have shown that following activation of G protein subsets by phospholipase C-β, mouse Tubby was transferred from the cytoplasmic membrane to the center [13, 14]. TLP gene family members contained a tubby domain about 270 amino acids in the C-terminal, and a plurality of different domains in the N-terminal. Diversity of the N-terminal indicated the diversity functions of TLP genes [11, 15]. In 1999, Shapiro Lab published the crystal structure of the tubby domain, laying the foundation for studying its function [16].

The spatial structure of the tubby domain consisted of a hydrophobic α-helix and a 12-fold inverted β-fold. The hydrophobic α-helix was located at the C-terminus of TLP protein [16, 17]. Unlike the diversity of N-terminal structures in animals, the N-terminus of TLP protein in plants often contained a conserved F-box domain [16, 18]. This F-box domain was first described as a sequence motif of cyclin F, and it interacted with the protein S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1). Experimental results indicated that SKP1 could bridge different F-box proteins to CDC53(Cullin), forming the designated SKP1/Cullin/F-box (SCF) complexes, which function in recognizing of target proteins specifically for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. F-box proteins regulated different biological processes, including cell cycle cycling, translational control, and signal transduction. For example, TIR1 was involved in auxin response during plant growth and development, and UFO was critical in flower organ identity determination [19–21], COI1 participated in jasmonic acid mediated defense response [22, 23], and ZTL or FKF1 control circadian clock [24, 25].

The TLP genes were widespread in many plants [26]. In Oryza sativa, A. thaliana, Zea mays, Malus domestica, Cicer arietinum and other plants, a genome-wide TLP gene family has been studied [27–30]. However, it has not been reported in Brassica crops, especially in B. napus. Therefore, this study used bioinformatics tools to conduct the comprehensively analyses of Brassica TLP gene family, including identification, gene structure, chromosomal distribution, orthologous and paralogous, duplication and loss, and expression pattern analyses at the genome level. Furthermore, comparative analyses were conducted with its two native parents (B. rapa and B. oleracea) and A. thaliana. This study will lay the foundation for further investigating the biological function of this family members in B. napus. At the same time, it provided a methodological reference for studying this gene family in other oil crops and related species.

Results

Identification and comparative analysis of TLP gene family in B. napus

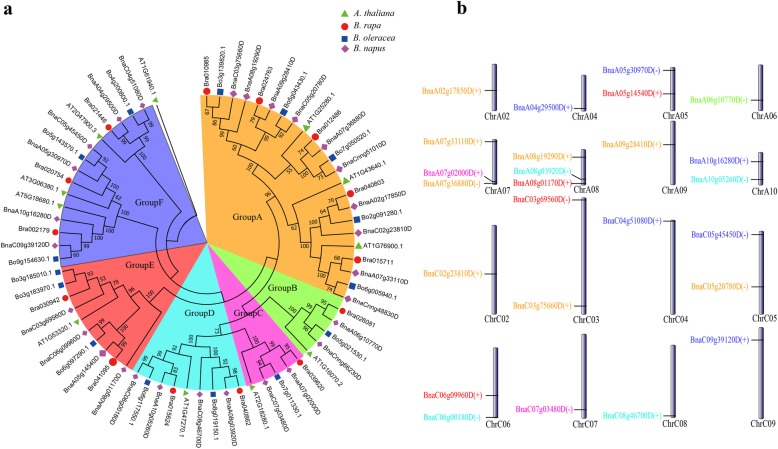

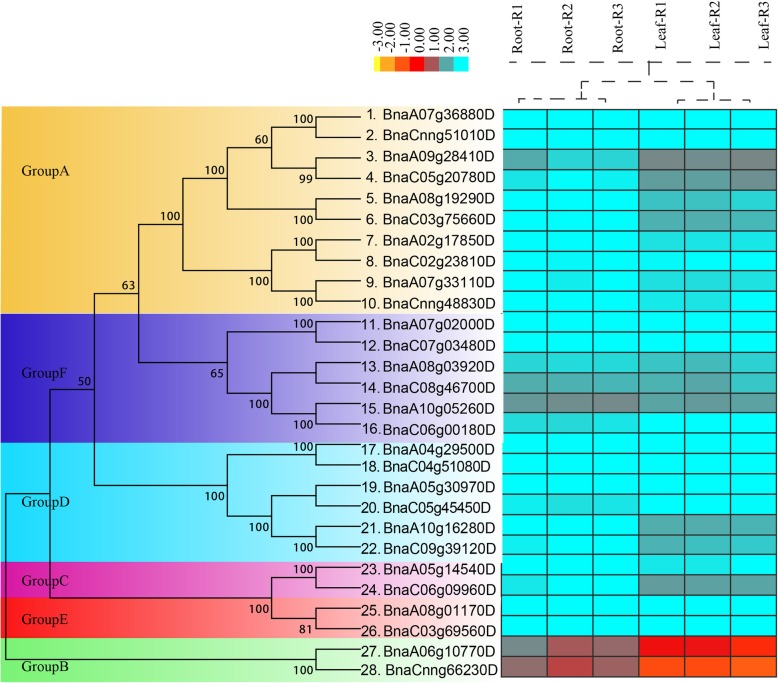

Totally, 29 TLP transcription factor members were identified from the whole genome of B. napus using bioinformatics methods (Table 1). Further analysis showed that the domain of gene (BnaC09g39130D) was incomplete and removed in the subsequent analysis. In order to explore the structure and biological function of TLP family genes in B. napus, we compared them with the model plant A. thaliana. The results showed that TLP family genes of B. napus had a high homology with A. thaliana corresponding genes (E-value<7E-136 ~ 0), which provided a good guidance for studying the function of TLP family genes in B. napus. Among the 28 B. napus genes identified, BnaA10g05260D was the longest, over 4145 bp; BnaC04g51080D was the shortest, only 1586 bp (Table 1). To investigate the evolutionary relationship of this family in Brassicaceae crops, we identified 14, 15 and 11 TLP family genes from B. rapa, B. oleracea. and A. thaliana, respectively. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using TLP family genes of these four species (Fig. 1a). According to the topology of phylogenetic tree, 28 BnTLPs were divided into 6 groups, named Group A to F. It could be seen from the phylogenetic tree that Group A contains the most TLP family genes, with 10 genes in B. napus, followed by Group F (6), Group D (4), and Group E (4). In Group A, there were 5 genes from subgenome A, and 3 genes from subgenome C.

Table 1.

The summary of TLP gene family members in B. napus and compared with A. thaliana

| B. napus | Gene start | Gene end | Gene length | Group | A. thaliana | Identity (%) | E-value | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BnaC03g75660D | 4,377,802 | 4,380,799 | 2997 | A | AT1G25280.1 | 84.56 | 0 | 711 |

| BnaA04g29500D | 1,400,068 | 1,402,078 | 2010 | D | AT2G47900.3 | 88.29 | 0 | 692 |

| BnaA07g36880D | 741,264 | 743,428 | 2164 | A | AT1G25280.1 | 88.42 | 0 | 730 |

| BnaA05g30970D | 21,446,109 | 21,448,431 | 2322 | D | AT3G06380.1 | 76.04 | 0 | 587 |

| BnaC07g03480D | 4,680,016 | 4,682,051 | 2035 | F | AT2G18280.1 | 86.04 | 0 | 629 |

| BnaC03g69560D | 59,391,825 | 59,394,400 | 2575 | E | AT1G53320.1 | 91.32 | 0 | 622 |

| BnaA05g14540D | 8,994,374 | 8,996,696 | 2322 | C | AT1G53320.1 | 86.43 | 0 | 619 |

| BnaC04g51080D | 48,418,230 | 48,419,816 | 1586 | D | AT2G47900.3 | 87.32 | 0 | 654 |

| BnaC08g46700D | 945,065 | 946,978 | 1913 | F | AT1G47270.1 | 77.27 | 0 | 572 |

| BnaCnng48830D | 48,277,183 | 48,280,749 | 3566 | A | AT1G76900.1 | 81.68 | 0 | 731 |

| BnaCnng51010D | 50,479,652 | 50,481,521 | 1869 | A | AT1G25280.1 | 85.52 | 0 | 723 |

| BnaA06g10770D | 5,654,536 | 5,656,427 | 1891 | B | AT1G16070.2 | 86.72 | 0 | 707 |

| BnaA08g19290D | 14,882,996 | 14,886,001 | 3005 | A | AT1G25280.1 | 85.27 | 0 | 709 |

| BnaA09g28410D | 21,293,066 | 21,295,808 | 2742 | A | AT1G25280.1 | 85.97 | 0 | 702 |

| BnaC02g23810D | 20,887,558 | 20,890,224 | 2666 | A | AT1G76900.1 | 83.41 | 0 | 744 |

| BnaC09g39120D | 41,813,712 | 41,815,558 | 1846 | D | AT5G18680.1 | 86.55 | 7.00E-136 | 387 |

| BnaC06g09960D | 11,871,153 | 11,873,618 | 2465 | C | AT1G53320.1 | 86.7 | 0 | 638 |

| BnaA02g17850D | 10,791,533 | 10,794,166 | 2633 | A | AT1G76900.1 | 84.13 | 0 | 738 |

| BnaA07g02000D | 1,660,832 | 1,662,975 | 2143 | F | AT2G18280.1 | 85.53 | 0 | 608 |

| BnaCnng66230D | 65,942,721 | 65,944,602 | 1881 | E | AT1G16070.2 | 86.22 | 0 | 710 |

| BnaA08g03920D | 3,231,533 | 3,233,325 | 1792 | F | AT1G47270.1 | 81.27 | 0 | 624 |

| BnaC06g00180D | 279,021 | 281,085 | 2064 | F | AT1G47270.1 | 84.14 | 0 | 651 |

| BnaA08g01170D | 891,151 | 893,938 | 2787 | E | AT1G53320.1 | 87.99 | 0 | 595 |

| BnaC05g45450D | 41,346,349 | 41,348,694 | 2345 | D | AT3G06380.1 | 78.39 | 0 | 603 |

| BnaA10g05260D | 3,001,258 | 3,005,403 | 4145 | F | AT1G47270.1 | 79.9 | 0 | 615 |

| BnaC05g20780D | 14,250,016 | 14,252,879 | 2863 | A | AT1G25280.1 | 83.93 | 0 | 664 |

| BnaA07g33110D | 22,783,241 | 22,786,597 | 3356 | A | AT1G76900.1 | 81.72 | 0 | 731 |

| BnaA10g16280D | 12,422,564 | 12,424,770 | 2206 | D | AT5G18680.1 | 83.59 | 0 | 611 |

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship and chromosome distribution analyses of TLP gene family. a The construction of phylogenetic tress using the TLP gene family among B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and A. thaliana. Phylogenetic tree topology was generated by MEGA7.0. For the major nodes, neighbour-joining (NJ) bootstrap values above 50% are shown. The Groups A to F indicate the groups obtained by bootstrap values and phylogenetic topology. b The distribution of B. napus TLP transcription factors on chromosomes. The genes with different colors correspond to above mentioned 6 groups on phylogenetic tree

Chromosome distribution analysis of TLP family genes in B. napus

To more intuitively understand the distribution of TLP family genes on the chromosomes of B. napus, we performed a chromosomal localization analysis (Fig. 1b). Since the genomic data of B. napus has not yet been fully mapped to the chromosome, the chromosomal location of some genes are still unclear, so these genes are not shown on the map (two genes, BnaCnng51010D and BnaCnng66230D). The localization information showed that members of this family were distributed in 16 of 19 chromosomes of B. napus. There was no TLP gene distribution on the three chromosomes of ChrA01, ChrA03 and ChrC01. ChrA07 and ChrA08 chromosomes had the most genes (3 genes). For the same group of genes, they were also distributed on multiple chromosomes, and there was no obvious phenomenon that the genes in the same group were clustered in a certain interval. For example, the six genes in Group F were distributed on six chromosomes. However, the distribution of genes on chromosomes was not uniform. Most genes were distributed at both ends of the chromosome (such as ChrA04, ChrA07, ChrA08, ChrC04, ChrC05, ChrC07, ChrC08), and there were fewer TLP genes near the centromere. This may be due to the fact that there are more repeat sequences in centromere, resulting in a small distribution of genes on the whole [31, 32].

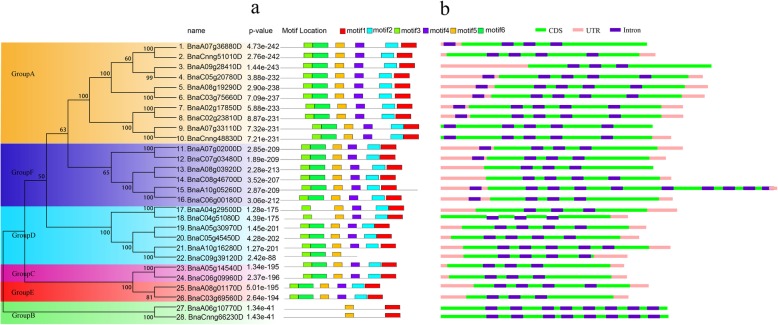

Conservative motif and gene structure analyses of TLP gene family

The sequence characteristics of 28 TLP genes in B. napus were analyzed using MEME software (Fig. 2a), and a total of 6 conserved motifs were obtained. The position of motif3 was in the front, and the position of motif1 and motif2 were backward. Twenty-three genes contained all six conserved motifs from motif1 to motif6. BnaA04g29500D and BnaA05g51080D (GroupD) lacked motif6; BnaA09g39120D (GroupD) lacked motif1, motif2 and motif4; BnaA06g10770D and BnaCnng66230D (GroupB) lacked motif2, motif3, motif4, motif6. The results showed that there was no loss of any conservative motifs in the four groups (GroupA, GroupC, GroupE, and GroupF). Of the 6 genes in GroupD, 3 of them lost part of the conserved motif. We found that motif5 was present in all 28 TLP genes in B. napus, indicating its presence or absence as a marker for the identification of TLP genes. In addition, motif1 was lost only in one gene (BnaA09g39120D), and motif3 was lost only in two genes (BnaA06g10770D and BnaCnng66230D). This indicated that these conserved motifs were relatively conservative and might play a very important role in the function of TLP gene family. Taken together, these results indicated that the gene conservation motifs within the group were relatively consistent and had a more consistent positional distribution across the genes.

Fig. 2.

The converted motif and gene structure analyses of TLP gene family in B. napus. a The motif identification of TLP gene family in B. napus. b The gene structure of TLP gene family in B. napus

In the study of molecular evolution, the distribution of introns provided important evidence for the phylogenetic relationship among members of the gene family. Gene structure analysis showed that TLP gene family structure of B. napus was relatively complex, and each gene contained introns (Fig. 2b). BnaA06g05260D contained the most introns and had 10 introns, followed by BnaA06g10770D and BnaCnng66230D with 8 introns. From the perspective of gene length, BnaA10g05260D was significantly longer than other genes. The three genes BnaA06g10770D, BnaCnng66230D and BnaA07g33110D lacked UTR region at two ends, while some genes lacked UTR region at one end. Through gene structure analysis, it was found that the genes in the same group had similar intron/exon distribution patterns. For example, two genes in the GroupB had almost the same genetic structure distribution characteristics.

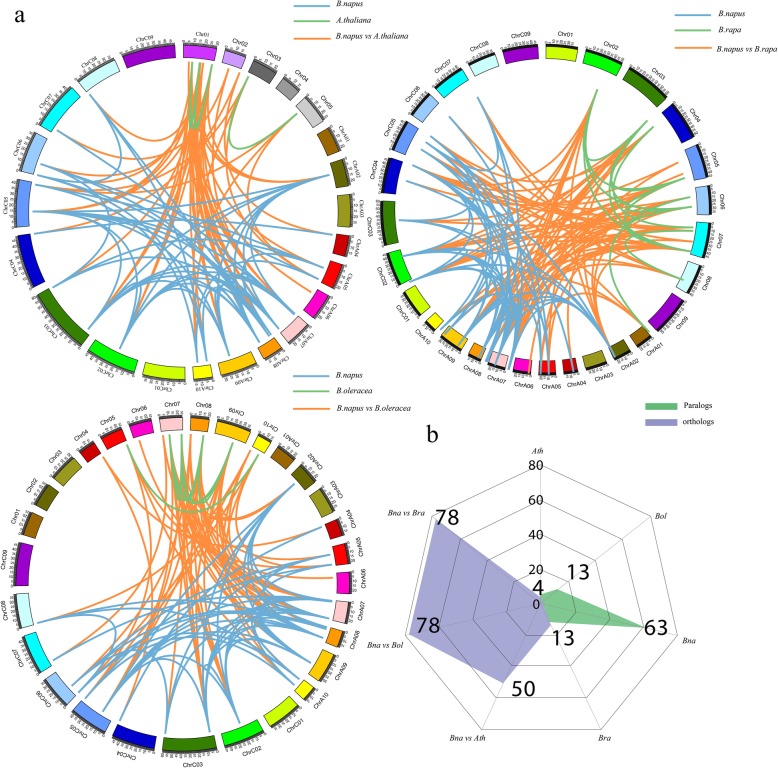

Analysis of orthologous and paralogous TLP family genes in Brassicaceae crops

We further analyzed the orthologous and paralogous of TLP gene family between B. napus and A. thaliana, B. rapa, or B. oleracea. The orthologous and paralogous network maps between B. napus and these three species were constructed by Circos program (Fig. 3a). Orthologs referred to genes that have evolved from vertical pedigrees from different species and typically retained the same function as the original gene. Here, 50 pairs of orthologous genes were identified in B. napus and A. thaliana; 78 pairs of orthologous genes were identified in B. napus and two diploid parents, B. rapa, B. oleracea (Fig. 3b, Table S1). Paralogs referred to genes that were found in the same species and derived from gene duplication, and might evolve new and previously related functions. A total of 4, 13, 13 and 63 pairs of paralogous genes were identified in A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. oleracea and B. napus (Fig. 3b, Table S2).

Fig. 3.

The paralogous and orthologous analyses of TLP gene family. a The plot of paralogous and orthologous TLP gene pairs between B. napus and A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. oleracea, respectively. b The statistics analysis of paralogous and orthologous of TLP gene family among four species

In addition, the divergence time and selection types of orthologous TLP gene pairs were calculated according to the nonsynonymous substitutions (Ka) and synonymous (Ks). To avoid the misalignment, we only used the orthologous gene pairs with Ks < 1 according to previous report [33]. Finally, we obtained the Ks, Ka, Ka/Ks, selection types, and divergence time of 133 orthologous gene pairs (Table S3). The results showed that most of orthologous gene pairs (132/133) had Ka/Ks ratios < 1, indicating purifying selection on these orthologous TLP gene pairs. Furthermore, we estimated the divergence time of orthologous TLP gene pairs according to synonymous substitution rate (Table S3). The results indicated that the divergence time was 12.81~31.89 million years ago (Mya) for 28 orthologous TLP gene pairs between B. napus and A. thaliana. Based on the divergence time (14.5 Mya) of B. napus and A. thaliana, 22 and 6 orthologous genes pairs were formed before and after the divergence of B. napus and A. thaliana, respectively. The divergence time was from 0.12 to 29.80 Mya for the orthologous TLP gene pairs between B. napus and B. oleracea. Based on the divergence time (0.045 Mya) of B. napus and B. oleracea, all 52 orthologous genes pairs were formed before the divergence of B. napus and B. oleracea. Similar, the divergence time of orthologous TLP gene pairs was 0.25~32.14 Mya between B. napus and B. rapa. Based on the divergence time (0.045 Mya) of B. napus and B. rapa, all 53 orthologous genes pairs were formed before the divergence of B. napus and B. rapa.

Duplicated type identification and synteny analyses of B. napus and other 3 species

The gene duplications have contributed to the expansion of gene family. We examined 5 types of gene duplications: singleton, dispersed, proximal, tandem, and WGD or segmental duplication by MCScanX program (Table 2, Table S4). Here, we found evidence that WGD likely contributed most to the expansion of this gene family in B. napus and B. oleracea. The percentage of WGD was 82.1% in B. napus, B. rapa (35.7.0%), B. oleracea (80.0%), and A. thaliana (18.2%) (Table 2). However, dispersed duplication contributed most to gene expansion in B. rapa (64.3%) and A. thaliana (72.7%). No proximal and tandem duplication were detected for TLP gene family among these four species. Actually, by checking gene collinearity within a genome, we found that 82.1, 35.7, 80.0 and 18.2% of TLP genes were located in collinear blocks for B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and A. thaliana, respectively (Table 3). The percentage of TLP genes located in the collinear blocks was significantly larger than the average genome-wide level for B. napus and B. oleracea.

Table 2.

The identification of duplicated type for TLP genes and all genes in B. napus and other three Brassicaceae species

| Species | Singleton | Dispersed | Proximal | Tandem | WGD or segmental | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome | TLP | Genome | TLP | Genome | TLP | Genome | TLP | Genome | TLP | Percentage | Genome | TLP | |

| B. napus | 7768 | 0 | 26,907 | 5 | 2428 | 0 | 2708 | 0 | 61,229 | 23 | 82.1% | 101,040 | 28 |

| B. rapa | 3666 | 0 | 10,622 | 9 | 873 | 0 | 2369 | 0 | 23,489 | 5 | 35.7% | 41,019 | 14 |

| B. oleracea | 4807 | 0 | 25,232 | 3 | 2515 | 0 | 2523 | 0 | 24,148 | 12 | 80.0% | 59,225 | 15 |

| A. thaliana | 5156 | 1 | 10,670 | 8 | 1046 | 0 | 3026 | 0 | 7519 | 2 | 18.2% | 27,417 | 11 |

Table 3.

The synteny analyses of TLP genes and all genes in B. napus and other three Brassicaceae species

| Species | All genes | TLP genes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total collinear blocks | Gene number in collinear blocks | Total genes | Percentage (%) | Collinear blocks contained TLP gene | TLP gene in collinear block | Total TLP genes | Percentage (%) | |

| B. napus | 2914 | 61,229 | 101,040 | 60.6 | 24 | 23 | 28 | 82.1 |

| B. rapa | 650 | 23,489 | 41,019 | 57.3 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 35.7 |

| B. oleracea | 747 | 24,148 | 59,225 | 40.8 | 8 | 12 | 15 | 80.0 |

| A. thaliana | 216 | 7519 | 27,417 | 27.4 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 18.2 |

Expansion analysis of TLP gene family in Brassica species

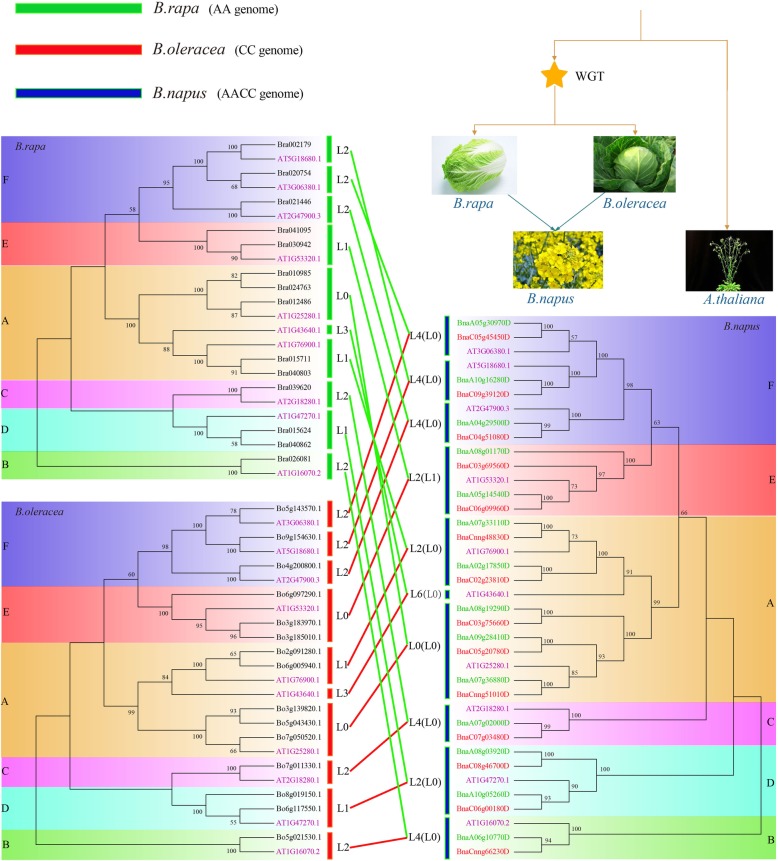

In order to further explore whether the expansion of TLP gene family in B. napus was a direct or indirect expansion, we conducted a more detailed analysis. In general, for most genome-wide replication events, including WGD (whole genome duplication) and WGT (whole genome triplication), replication was accompanied by loss of genes [34, 35]. To elucidate the evolution of TLP gene family in Brassica, we performed gene loss and replication retention analysis. Compared with A. thaliana, a WGT and hybridization event occurred in B. napus after differentiation with A. thaliana [4–6]. Here, 11 TLP family genes were identified in A. thaliana. In theory, there should be 66 TLP genes in B. napus (11 × 3 × 2), while only 28 TLP genes were identified in B. napus. Although a WGT event occurred after the differentiation of Brassica species and A. thaliana, the number of TLP genes did not increase significantly. There were only 14 and 15 genes in B. rapa and B. oleracea species, indicating that this WGT event did not result in a significant expansion of the TLP gene, or a gene loss occurred after expansion.

We obtained quantitative changes in the number of TLP genes in different evolutionary stages based on the phylogenetic reconstruction (Fig. 4). In phylogenetic tree of A. thaliana and B. rapa, one A. thaliana gene should theoretically correspond to three genes of B. rapa, but we clearly saw that one A. thaliana gene corresponded to only one gene in B. rapa for GroupB, GroupC and GroupF, and two genes were lost. The gene (AT1G25280) in GroupA was completely retained after WGT in B. rapa (AT1G25280 vs Bra010985, Bra024763 and Bra012486), indicating that these genes might play a very important role in B. rapa. In particular, it might be a gene dosage effect, explaining the significant differences between B. rapa and A. thaliana for some certain traits. The gene corresponding to AT1G43640 in GroupA was completed lost in B. rapa, indicating that this gene might not function in B. rapa. In GroupD and E, one gene was lost in B. rapa corresponding to A. thaliana.

Fig. 4.

The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. napus, B. rapa, B. oleracea compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes

In phylogenetic tree of A. thaliana and B. oleracea (Fig. 4), the loss of gene in GroupA, B, C, D, and F was consistent with that of B. rapa. In GroupE, three genes of B. oleracea were not lost (AT1G53320 vs Bo6g097290, Bo3g183970 and Bo3g185010). In B. rapa, there were only two copies of this gene in A. thaliana, and a gene loss occurs in GroupE.

In phylogenetic tree of A. thaliana and B. napus (Fig. 4), one A. thaliana gene corresponded to six B. napus genes. The TLP gene in B. napus had a lot of loss after WGT event. In fact, the loss number of each group varied from 2 to 6 genes. For example, the gene corresponding to AT1G43640 had all been lost in B. napus. However, the six genes corresponding to AT1G25280 were all retained in B. napus. In fact, based on the analysis of B. oleracea and B. rapa, it was clear that the loss of TLP gene did not occur directly in B. napus. The loss of TLP genes occurred during the WGD event of the diploid parents B. oleracea and B. rapa. The phylogenetic tree connection showed that the total number of genes in each group of B. napus has been evolved to be sum of the number of corresponding groups of B. oleracea and B. rapa (28 vs 14 + 15). Only in GroupE, the number of B. rapa relative to A. thaliana genes was lost (Ath: 1 vs Bra: 2), and B. oleracea gene was not lost (Ath: 1 vs Bol: 3). Therefore, there should be 5 TLP genes in GroupE of B. napus. However, we found that there were only 4 TLP genes in this group, which meant that 1 gene was lost after the formation of B. napus. Of course, there was also a case that we originally filtered out BnaC09g39130D from subgenome C, which was most likely from this group. However, a significant domain was loss in this gene, resulting in the failure to this group. In summary, we found that the genes in B. napus did not directly expand compared to their diploid parents B. oleracea and B. rapa. Thus, the expansion of this gene family of B. napus is an indirect expansion, that is, the expansion occurred in its two diploid parents.

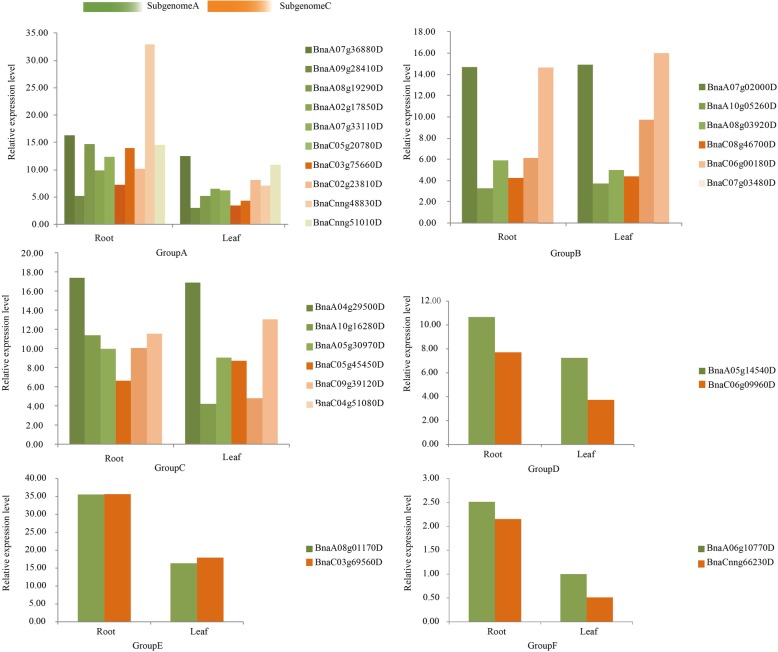

Gene expression pattern analysis of TLP gene family in B. napus

To explore the potential function of TLP family genes in different tissues of B. napus, the transcriptome data was used to calculate the expression of TLP family genes in two tissues, including roots and leaves. The expression levels were estimated by RPKM, and the deeper of the blue, the higher of the expression (Fig. 5, Table S5). The results showed that most of TLP genes had higher expression levels in roots and leaves except for the low expression levels of the two genes in GroupB. Of course, the expression patterns of some TLP genes in two tissues were slightly different. For example, the expression levels of BnaA09g28410, BnaC05g20780D, BnaA10g16280D, BnaC09g39120D and BnaC06g09960D in roots were higher than those in leaves.

Fig. 5.

The expression hierarchical clustering of TLP genes in B. napus. The gene expression in roots (R1, R2, and R3 for three replicates) and leaves (L1, L2, and L3) were determined by RNA-seq. The expression values were calculated by RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads), and the expression values were log2 transformed

In addition, we also compared the expression differences of TLP genes in roots and leaves in subgenome A and subgenome C for each group (Fig. 6). The results showed that the expression patterns of TLP genes between subgenome A and subgenome C were similar. BnaCnng48830D in GroupA was highly expressed compared to other genes. The expression of BnaA09g28410D and BnaC05g20780D, BnaA08g19290D, BnaC03g75660D, BnaA10g16280D, BnaC06g09960D, BnaC09g39120D in roots were significantly higher than that in leaves, indicating that these genes might play an important role in the morphogenesis of roots. The expression of BnaA06g10770D and BnaCnng66230D were extremely low in roots and leaves of B. napus. Several genes were also highly expressed in roots and leaves, such as BnaA07g36880D and BnaCnng51010D, BnaA08g01170D and BnaC03g69560D. These genes might be involved in the transcriptional regulation of various physiological and biochemical change in the whole growth and development cycle of B. napus. In conclusion, it was found that not only the group had similar conservative motifs, but also had similar expression patterns, which made the gene structure and function uniform.

Fig. 6.

Histogram of TLP gene expression in root and leaf of in B. napus. Group A to Group F represent 6 groups classified by TLP genes. The genes located in subgenome A of B. napus were marked green, and the genes located subgenome C were marked red

Discussion

Systematical and comprehensive analyses of TLP gene family in B. napus

This study systematically compared and analyzed the TLP gene family of B. napus on the basis of predecessors. Up to now, we have systematically analyzed multiple gene families of B. rapa and B. napus, such as BES1, AP2/ERF, CO-Like, bHLH, BES1, HSF, GARS, and cold-related genes [36–46]. The methods, techniques, and experiences of these studies laid the foundation for an in-depth analysis of TLP gene family. In order to further analyze the evolutionary relationship between B. napus and other species homologous genes, this study constructed a phylogenetic tree of B. napus and B. rapa, A. thaliana and B. oleracea TLP family genes. In the structural analysis of TLP genes, it was found that the gene family structure of B. napus was relatively complicated. In the paralogous gene analysis, it was found that there were 63 pairs of paralogous genes in B. napus. So many paralogous genes also gave us a new understanding of the TLP gene family in B. napus.

Evolution and expansion of TLP gene family in Brassica species

In the analysis of the duplication and loss of TLP gene family during evolution, we found a very interesting gene, the A. thaliana AT1G25280 gene from GroupA group. The gene corresponded to 3, 3 and 6 TLP genes in B. oleracea, B. rapa and B. napus, respectively. It indicated that all copies of this gene are preserved after WGT in Brassica crops, which was in accordance with 1:3:6 duplication ratios. It indicated that they might have very important functions for the growth and development of Brassica and even in B. napus. Of course, the opposite evolutionary pattern was the AT1G43640 gene of A. thaliana. Its homologous genes were not detected in B. oleracea, B. rapa and B. napus, that was, the gene was completely lost after WGT event. This indicated that the gene might not play any functional role for Brassica genus. In addition, this study found that the loss of TLP family genes was not directly in the B. napus genome through comparative analysis. It occured in the WGD process of the diploid parents B. rapa and B. oleracea. Therefore, the TLP family genes in B. napus did not directly expand compared to their two diploid parents. Thus, the expansion of this gene family in B. napus was an indirect expansion, that was, the expansion of this family genes in its two diploid parents.

In addition, we also identified TLP gene family in other Brassica species for comparative analyses. Totally, 42, 28, 14, 13, and 14 TLP genes were detected in the B. napus ‘ZS11’, B. napus ‘Tapidor’, B. rapa ‘Z1’ (yellow sarson), B. oleracea ‘kale-like’, and B. oleracea ‘HDEM’ (broccoli) (Figs. S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5). We found that the number of the TLP genes in these species except B. napus ‘ZS11’ was similar with the 3 Brassica species used in our study. The TLP genes in B. napus ‘ZS11’ was more than that in other B. napus species. This might be due to genome assembly and gene prediction, because the number of genome-wide genes in B. napus ‘ZS11’ (123,465) was also more than that in B. napus ‘Tapidor’ (70,162) and B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ (101,040).

Furthermore, we have performed the analysis of gene duplication and loss. It was found that the evolution pattern of most TLP genes in these species had similar patterns of duplication and loss as the three Brassica species we studied (Figs. S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5). However, there were some inconsistencies among these species. For example, compared with the AT1G25280.1 gene in Arabidopsis, no homologous gene was lost in B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ and B. napus ‘ZS11’, while one gene was lost in B. napus ‘Tapidor’. Compared with the AT1G47270.1, two gene were lost in B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ and B. napus ‘Tapidor ‘, while three genes were lost in B. napus ‘ZS11’. Compared to the AT1G16070.2, four genes were lost in B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ and B. napus ‘ZS11’, while only one gene was lost in B. napus ‘Tapidor ‘.

Exploring TLP gene function in more species

In recent years, with the deepening of TLP gene research, it has been found that they played a major role in plant growth, development and stress response. Studying the distribution, gene structure and expression analysis of TLP family genes in plant was great significant for further study of their function. In previous studies on TLP genes, 11 TLP family members have been found in A. thaliana, 14 family members in O. sativa, and 15 TLP family members in maize. The widespread presence of TLP genes indicated that they played an extremely important role in the life process [28, 29]. For example, a partial disease phenotype was produced when a genetic mutation occurred in a TLP gene. Although the function of TLP family genes in animals and plants has not yet been fully clarified, some research results have been obtained on the mining and research of their function and structure. The highly conserved nature of TLP domain indicated that they had important physiological functions in multicellular eukaryotes [16–18]. In particular, studies of plant TLP gene family have revealed that multiple TLP genes were involved in plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses [15, 27]. This indicated that TLP genes could be used as candidate genes for plant stress-resistant breeding and applied to plant resistance breeding. The comparative genomics study of TLP gene family of B. napus in this research system will inevitably lay a solid foundation for the functional study of TLP gene family.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we comprehensively analyzed the evolutionary pattern, gene structure, orthologous and paralogous genes, duplication type, gene synteny, gene duplication or losses, and gene expression pattern of TLP genes in B. napus and other Brassicaceae species. A total of 68 TLP genes were identified in these species, and 28 genes were identified in B. napus. Identification of these transcription factor genes was likely to assist in clarifying the molecular genetics basis for B. napus genetic improvement, and also provided the functional gene resources for transgenic research. Until now, few genes representing this gene family have been characterized in detail from B. napus. Therefore, this is the first comprehensive and systematic analyses of TLP gene family in B. napus. This study provides useful resources for future studies on the structure and function of TLP genes in B. napus. In addition, our analyses showed that the directly expansion of TLP genes existed in B. napus, and the real TLP expansion occurred in its diploid parents B. rapa and B. oleracea. This study may also facilitate our understanding of the effect of duplication or losses during the evolution of B. napus or others polyploidy.

Methods

Collection of genomic data and identification of TLP gene family

The A. thaliana genome-related data used in this study was derived from Tair website (Tair10, https://www.arabidopsis.org). B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ (v5.0) and B. rapa ‘Chiifu’ (v3.0) genomic data were derived from BRAD database (http://brassicadb.org/brad/index.php) [1]. B. oleracea var. capitata line 02–12 genome (v1.1) datasets were derived from Bolbase database (http://www.ocri-genomics.org/bolbase/index.html) [4]. The protein sequences of B. rapa ‘Z1’ (yellow sarson) and B. oleracea ‘HDEM’ (broccoli) were downloaded from genoscope (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/plants/chromosomes.html) [47]. The genome sequences of B. oleracea kale-like type TO1000 were downloaded from EMBL [6]. The genome sequences of B. napus ‘ZS11’ (v2.0) were derived from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/203), and B. napus ‘Tapidor’ (v6.3) genome sequences were downloaded from applied bioinformatics group (http://appliedbioinformatics.com.au/index.php/Darmor_Tapidor) [48]. The Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk) database was used to perform domain search on the amino acid sequences of the downloaded species, and the genes containing “TLP” domain were extracted by the self-programmed Perl program (PF01167). At the same time, in order to ensure the accuracy of the results, the SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/change_mode.pl) and CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd) databases were further used to perform domain validation on the genes identified above [30, 49].

Gene structural and conservative motif analyses of TLP genes in B. napus

Information on the location of TLP genes in B. napus, such as chromosome, genomic location, CDS, protein sequence, etc., were obtained from the databases mentioned above. The gene structure was analyzed by the online tool GSDS (http://gss.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php) [50]. It could show the position of introns, exons, and un-translated regions (UTRs) of the gene. The gff file of TLP family genes was submitted to the GSDS program to obtain a schematic diagram of the gene structure. The online analysis software MEME (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme4-1/cgi-bin/meme.cgi) was used to analyze the amino acid sequence of TLP genes in B. napus, and 6 motifs were obtained and used for further analyses.

Evolution analysis of TLP gene family in B. napus

The ClustalW program was used to perform multiple alignments of the amino acid sequences of the TLP gene family using default parameter values (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw). The incomplete reading frame sequences and redundant sequences were manually removed. The phylogenetic tree of TLP gene family was constructed with Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method using Mega7.0 software (http://megasoftware.net) [51, 52]. The evolutionary tree was evaluated by Bootstrap method, and the value was set as1000 [51]. The position information on the chromosome of TLP family genes was extracted from gff file, and the chromosome map was drawn using Perl program.

Identification of orthologous and paralogous genes

The orthologous and paralogous relationships between the TLP genes of B. napus and A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. oleracea were identified using OrthoMCL software (http://orthomcl.org/orthomcl/) [53]. Images of the relationships between the paralogous and orthologous of A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. oleracea, and B. napus were drawn using Circos software (http://circos.ca/) [54].

Ka/Ks calculation and dating the divergent time

To estimate the divergence of orthologous genes, the sequences of orthologous TLP gene pairs between B. napus and other three species (A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. oleracea) were aligned using ClustalW (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw). Then, the nonsynonymous rate (Ka), synonymous rate (Ks), and evolutionary constraint (Ka/Ks) between the orthologous gene pairs were calculated according to their coding sequence alignments by using Nei-Gojobori method implemented in the Ka/Ks_calculator program [55, 56]. The orthologous gene pairs with Ks < 1 were used for the divergence time estimation based on the neutral substitution rate 1.5 × 10− 8 substitutions per site per year [57].

Analysis of expression pattern of TLP gene family in B. napus

The RNA-seq data was used to analyze TLP gene expression patterns in leaves and roots in B. napus [58]. This dataset contained three replicates, and RPKM value was log10 transformed. The average value was used to compare the expression level of TLP genes between subgenome A and C, or root and leaf. The heatmap package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html) of R was used to draw the expression heatmap.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. The list of orthologous TLP gene pairs between B. napus, A. thaliana, B. rapa, and B. oleracea. Table S2. The list of paralogous TLP gene pairs in each of other examined species. Table S3. Ka/Ks calculation and divergent time of the orthologous gene pairs between B. napus and other 3 species. Table S4. The duplicated type of TLP genes in B. napus and other three brassicaceae species. The 0 to 4 indicate the singleton, dispersed, proximal, tandem, WGD duplication type, respectively. Table S5. The expression level of the TLP genes in root and leaf for B. napus. The gene expression was determined by the RNA-Seq data (RPKM).

Additional file 2: Figure S1. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. napus ‘ZS11’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S2. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. napus ‘Tapidor’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S3. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. oleracea ‘HDEM’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S4. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. oleracea ‘kale-like’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S5. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. rapa ‘Z1’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- TLP

Tubby-like proteins

- SKP1

S-phase kinase-associated protein 1

- WGD

Whole-genome duplication

- WGT

Whole-genome triplication

- CDS

Coding domain sequence

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived by X.S and N.L. X.S., T.W., J.H., C.L., X.M., Q.Y., S.F., and M.L contributed to data collection and bioinformatics analysis. X.S., N.L, T.W., J.H., C.L., and X.M participated in preparing and writing the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31801856), the Hebei Province Higher Education Youth Talents Program (BJ2018016), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei (C2017209103), and Hebei Province Postgraduate Demonstration Course-Genomics (KCJSX2018053).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study were included in this published article and the additional files.

A. thaliana genome: https://www.arabidopsis.org;

B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ and B. rapa ‘Chiifu’ genome: http://brassicadb.org/brad/index.php;

B. napus ‘ZS11’ genome: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/203;

B. napus ‘Tapidor’ genome: http://appliedbioinformatics.com.au/index.php/Darmor_Tapidor;

B. rapa ‘Z1’ genome: http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/plants/chromosomes.html;

B. oleracea var. capitata line 02–12 genome: http://www.ocri-genomics.org/bolbase/index.html;

B. oleracea ‘HDEM’: http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/plants/chromosomes.html.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tong Wang, Email: wangtong2317@163.com.

Jingjing Hu, Email: 18331563703@163.com.

Xiao Ma, Email: maxiaoxiaos@sina.com.

Chunjin Li, Email: lichunjin0424@163.com.

Qihang Yang, Email: yangqihang0504@163.com.

Shuyan Feng, Email: 15232617677@163.com.

Miaomiao Li, Email: miao15033908755@163.com.

Nan Li, Email: Limanxi1989@163.com.

Xiaoming Song, Email: songxm@ncst.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12864-020-6678-x.

References

- 1.Cheng F, Liu S, Wu J, Fang L, Sun S, Liu B, Li P, Hua W, Wang X. BRAD, the genetics and genomics database for Brassica plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalhoub B, Denoeud F, Liu S, Parkin IAP, Tang H, Wang X, Chiquet J, Belcram H, Tong C, Samans B. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345(6199):950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng F, Wu J, Wang X. Genome triplication drove the diversification of Brassica plants. Horticulture research. 2014;1:14024. doi: 10.1038/hortres.2014.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Liu Y, Yang X, Tong C, Edwards D, Parkin IAP, Zhao M, Ma J, Yu J, Huang S. The Brassica oleracea genome reveals the asymmetrical evolution of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 2014;5(5):3930. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consortium TBrGSP, Wang X, Wang H, Wang J, Sun R, Wu J, Liu S, Bai Y, Mun J-H, Bancroft I. The genome of the mesopolyploid crop species Brassica rapa. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1035–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Parkin IA, Koh C, Tang H, Robinson SJ, Kagale S, Clarke WE, Town CD, Nixon J, Krishnakumar V, Bidwell SL, et al. Transcriptome and methylome profiling reveals relics of genome dominance in the mesopolyploid Brassica oleracea. Genome Biol. 2014;15(6):R77. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng F, Mandakova T, Wu J, Xie Q, Lysak MA, Wang X. Deciphering the diploid ancestral genome of the Mesohexaploid Brassica rapa. Plant Cell. 2013;25(5):1541–1554. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.110486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woodhouse MR, Cheng F, Pires JC, Lisch D, Freeling M, Wang X. Origin, inheritance, and gene regulatory consequences of genome dominance in polyploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(14):5283–5288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402475111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng F, Sun R, Hou X, Zheng H, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Liu B, Liang J, Zhuang M, Liu Y, et al. Subgenome parallel selection is associated with morphotype diversification and convergent crop domestication in Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea. Nat Genet. 2016;48(10):1218–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng.3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishina PM, North MA, Ikeda A, Yan Y, Naggert JK. Molecular characterization of a novel tubby gene family member, TULP3, in mouse and humans ☆. Genomics. 1998;54(2):215–220. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikeda A, Nishina PM, Naggert JK. The tubby-like proteins, a family with roles in neuronal development and function. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 1):9–14. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleyn PW, Fan W, Kovats SG, Lee JJ, Pulido JC, Wu Y, Berkemeier LR, Misumi DJ, Holmgren L, Charlat O, et al. Identification and characterization of the mouse obesity gene tubby: a member of a novel gene family. Cell. 1996;85(2):281–290. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Seburn K, Bechtel L, Lee BY, Szatkiewicz JP, Nishina PM, Naggert JK. Defective carbohydrate metabolism in mice homozygous for the tubby mutation. Physiol Genomics. 2006;27(2):131–140. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00239.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickenson JM, Hill SJ. Activation of phospholipase C by G-protein beta gamma subunits in DDT1MF-2 cells. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23(1):17S. doi: 10.1042/bst023017s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukhopadhyay S, Jackson PK. The tubby family proteins. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):225. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boggon TJ, Shan WS, Santagata S, Myers SC, Shapiro L. Implication of tubby proteins as transcription factors by structure-based functional analysis. Science. 1999;286(5447):2119–2125. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badgandi HB, Hwang SH, Shimada IS, Loriot E, Mukhopadhyay S. Tubby family proteins are adapters for ciliary trafficking of integral membrane proteins. J Cell Biol. 2017;216(3):743–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang M, Xu Z, Kong Y. The tubby-like proteins kingdom in animals and plants. Gene. 2018;642:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wardhan V, Jahan K, Gupta S, Chennareddy S, Datta A, Chakraborty S, Chakraborty N. Overexpression of CaTLP1, a putative transcription factor in chickpea ( Cicer arietinum L.), promotes stress tolerance. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;79(4–5):479–493. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9925-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durfee T, Roe JL, Sessions RA, Inouye C, Serikawa K, Feldmann KA, Weigel D, Zambryski PC. The F-box-containing protein UFO and AGAMOUS participate in antagonistic pathways governing early petal development in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8571–8576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033043100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai CP, Lee CL, Chen PH, Wu SH, Yang CC, Shaw JF. Molecular analyses of the Arabidopsis TUBBY-like protein gene family. Plant Physiol. 2004;134(4):1586–1597. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan JB, Li HO, Li SH, Yao RF, Deng HT, Xie Q, Xie DX. The Arabidopsis F-box protein coronatine insensitive1 is stabilized by SCFCOI1 and degraded via the 26S proteasome pathway. Plant Cell. 2013;25(2):486–498. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang WJ, Liu GS, Niu HX, Timko MP, Zhang HB. The F-box protein COI1 functions upstream of MYB305 to regulate primary carbohydrate metabolism in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. TN90) J Exp Bot. 2014;65(8):2147–2160. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baudry A, Ito S, Song YH, Strait AA, Kiba T, Lu S, Henriques R, Pruneda-Paz JL, Chua NH, Tobin EM, et al. F-box proteins FKF1 and LKP2 act in concert with ZEITLUPE to control Arabidopsis clock progression. Plant Cell. 2010;22(3):606–622. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zoltowski BD, Imaizumi T. Structure and function of the ZTL/FKF1/LKP2 group proteins in Arabidopsis. The Enzymes. 2014;35:213–239. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801922-1.00009-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Zhou Y, Wang X, Gu S, Yu J, Liang G, Yan C, Xu C. Genomewide comparative phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analysis of tubby-like protein family in Arabidopsis, rice, and poplar. Genomics. 2008;92(4):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du F, Xu JN, Zhan CY, Yu ZB, Wang XY. An obesity-like gene MdTLP7 from apple ( Malus × domestica ) enhances abiotic stress tolerance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445(2):394–397. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kou Y, Qiu D, Lei W, Li X, Wang S. Molecular analyses of the rice tubby-like protein gene family and their response to bacterial infection. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28(1):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0620-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai CP, Jeifu S. Interaction analyses of Arabidopsis tubby-like proteins with ASK proteins. Bot Stud. 2015;53(4):447–458. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivica L, Tobias D, Peer B. SMART 7: recent updates to the protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):302–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melters DP, Bradnam KR, Young HA, Telis N, May MR, Ruby JG, Sebra R, Peluso P, Eid J, Rank D, et al. Comparative analysis of tandem repeats from hundreds of species reveals unique insights into centromere evolution. Genome Biol. 2013;14(1):R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukui KN, Suzuki G, Lagudah ES, Rahman S, Appels R, Yamamoto M, Mukai Y. Physical arrangement of retrotransposon-related repeats in centromeric regions of wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42(2):189–196. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo Y, Liu J, Zhang J, Liu S, Du J. Selective modes determine evolutionary rates, gene compactness and expression patterns in Brassica. Plant J. 2017;91(1):34–44. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mun JH, Kwon SJ, Yang TJ, Seol YJ, Jin M, Kim JA, Lim MH, Kim JS, Baek S, Choi BS, et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of the Brassica rapa gene space reveals genome shrinkage and differential loss of duplicated genes after whole genome triplication. Genome Biol. 2009;10(10):R111. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Bodt S, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Genome duplication and the origin of angiosperms. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20(11):591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song X, Duan W, Huang Z, Liu G, Wu P, Liu T, Li Y, Hou X. Comprehensive analysis of the flowering genes in Chinese cabbage and examination of evolutionary pattern of CO-like genes in plant kingdom. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14631. doi: 10.1038/srep14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song X, Li Y, Hou X. Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF transcription factor superfamily in Chinese cabbage ( Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis ) BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):573. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song X, Liu G, Duan W, Liu T, Huang Z, Ren J, Li Y, Hou X. Genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis of the heat shock transcription factor family in Chinese cabbage. Mol Genet Genomics. 2014;289(4):541–551. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0833-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song X, Ma X, Li C, Hu J, Yang Q, Wang T, Wang L, Wang J, Guo D, Ge W. Comprehensive analyses of the BES1 gene family in Brassica napus and examination of their evolutionary pattern in representative species. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):346. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4744-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song XM, Huang ZN, Duan WK, Ren J, Liu TK, Li Y, Hou XL. Genome-wide analysis of the bHLH transcription factor family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) Molecular genetics and genomics : MGG. 2014;289(1):77–91. doi: 10.1007/s00438-013-0791-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song XM, Liu TK, Duan WK, Ma QH, Ren J, Wang Z, Li Y, Hou XL. Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) Genomics. 2014;103(1):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duan W, Song X, Liu T, Huang Z, Ren J, Hou X, Du J, Li Y. Patterns of evolutionary conservation of ascorbic acid-related genes following whole-genome triplication in Brassica rapa. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;7(1):299–313. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song X, Wang J, Ma X, Li Y, Lei T, Wang L, Ge W, Guo D, Wang Z, Li C, et al. Origination, expansion, evolutionary trajectory, and expression Bias of AP2/ERF superfamily in Brassica napus. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1186. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, Zhao K, Pan Y, Wang J, Song X, Ge W, Yuan M, Lei T, Wang L, Zhang L, et al. Genomic, expressional, protein-protein interactional analysis of Trihelix transcription factor genes in Setaria italia and inference of their evolutionary trajectory. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):665. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song XM, Wang JP, Sun PC, Ma X, Yang QH, Hu JJ, Sun SR, Li YX, Yu JG, Feng SY, Pei QY, Yu T, Yang NS, Liu YZ, Li XQ, Paterson AH, Wang XY. Preferential gene retention increases the robustness of cold regulation in Brassicaceae and other plants after polyploidization. Hortic Res. 2020;7:20. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-0253-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan XL, Fan ZQ, Shan W, Yin XR, Kuang JF, Lu WJ, Chen JY. Association of BrERF72 with methyl jasmonate-induced leaf senescence of Chinese flowering cabbage through activating JA biosynthesis-related genes. Hortic Res. 2018;5:22. doi: 10.1038/s41438-018-0028-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belser C, Istace B, Denis E, Dubarry M, Baurens F-C, Falentin C, Genete M, Berrabah W, Chèvre A-M, Delourme R, et al. Chromosome-scale assemblies of plant genomes using nanopore long reads and optical maps. Nature Plants. 2018;4(11):879–887. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0289-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bayer PE, Hurgobin B, Golicz AA, Chan CK, Yuan Y, Lee H, Renton M, Meng J, Li R, Long Y, et al. Assembly and comparison of two closely related Brassica napus genomes. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(12):1602–1610. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marchlerbauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Deweesescott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M. CDD: specific functional annotation with the conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2014;31(8):1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2016;33(7):1870. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung BY, Hardcastle TJ, Jones JD, Irigoyen N, Firth AE, Baulcombe DC, Brierley I. The use of duplex-specific nuclease in ribosome profiling and a user-friendly software package for Ribo-seq data analysis. Rna-a Publication of the Rna Society. 2015;21(10):1731. doi: 10.1261/rna.052548.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13(9):2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol İ, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2010;8(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Z, Li J, Zhao XQ, Wang J, Wong GK, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2006;4(4):259–263. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koch MA, Haubold B, Mitchell-Olds T. Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae) Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(10):1483–1498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boulos C, France D, Shengyi L, Parkin IAP, Haibao T, Xiyin W, Julien C, Harry B, Chaobo T, Birgit S. Plant genetics. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science. 2014;345(6199):950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1253435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. The list of orthologous TLP gene pairs between B. napus, A. thaliana, B. rapa, and B. oleracea. Table S2. The list of paralogous TLP gene pairs in each of other examined species. Table S3. Ka/Ks calculation and divergent time of the orthologous gene pairs between B. napus and other 3 species. Table S4. The duplicated type of TLP genes in B. napus and other three brassicaceae species. The 0 to 4 indicate the singleton, dispersed, proximal, tandem, WGD duplication type, respectively. Table S5. The expression level of the TLP genes in root and leaf for B. napus. The gene expression was determined by the RNA-Seq data (RPKM).

Additional file 2: Figure S1. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. napus ‘ZS11’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S2. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. napus ‘Tapidor’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S3. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. oleracea ‘HDEM’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S4. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. oleracea ‘kale-like’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes. Figure S5. The duplication or loss analyses of TLP genes in B. rapa ‘Z1’ compared with A. thaliana. The “L”and “D” indicates the loss and duplication, respectively. The number after “L” and “D” represents the number of genes.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study were included in this published article and the additional files.

A. thaliana genome: https://www.arabidopsis.org;

B. napus ‘Darmor-bzh’ and B. rapa ‘Chiifu’ genome: http://brassicadb.org/brad/index.php;

B. napus ‘ZS11’ genome: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/203;

B. napus ‘Tapidor’ genome: http://appliedbioinformatics.com.au/index.php/Darmor_Tapidor;

B. rapa ‘Z1’ genome: http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/plants/chromosomes.html;

B. oleracea var. capitata line 02–12 genome: http://www.ocri-genomics.org/bolbase/index.html;

B. oleracea ‘HDEM’: http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/plants/chromosomes.html.