Abstract

Good mental health is related to mental and psychological well-being, and there is growing interest in the potential role of the built environment on mental health, yet the evidence base underpinning the direct or indirect effects of the built environment is not fully clear. The aim of this overview is to assess the effect of the built environment on mental health-related outcomes. Methods. This study provides an overview of published systematic reviews (SRs) that assess the effect of the built environment on mental health. We reported the overview according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Databases searched until November 2019 included the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, MEDLINE (OVID 1946 to present), LILACS, and PsycINFO. Two authors independently selected reviews, extracted data, and assessed the methodological quality of included reviews using the Assessing Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2). Results. In total, 357 records were identified from a structured search of five databases combined with the references of the included studies, and eleven SRs were included in the narrative synthesis. Outcomes included mental health and well-being, depression and stress, and psychological distress. According to AMSTAR-2 scores, the quality assessment of the included SRs was categorized as “high” in two SRs and as “critically low” in nine SRs. According to the conclusions of the SRs reported by the authors, only one SR reported a “beneficial” effect on mental health and well-being outcomes. Conclusion. There was insufficient evidence to make firm conclusions on the effects of built environment interventions on mental health outcomes (well-being, depression and stress, and psychological distress). The evidence collected reported high heterogeneity (outcomes and measures) and a moderate- to low-quality assessment among the included SRs.

1. Introduction

Mental health is the well-being of the individual and the sum of his/her abilities to contribute to the community and adequately handle the daily stages of stress [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in four people will be affected by a mental health problem at some point in their lives [2]. Mental disorders impose an enormous global disease burden, affecting every community and age group across all income countries [3], and it accounts for an estimated 32.4% of years lived with disability (YLDs) and 13.0% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [4].

The total economic output lost to these disorders was estimated to be one trillion USD per year due to lost production and consumption opportunities [5]. The global cost of mental disorders was estimated to be 2.5 trillion USD in 2010, and these costs could rise to six trillion USD by 2030 [6].

Mental health depends not only on individual characteristics but also on health determinants which require an analysis of the influence of the environment on the individual's ability to stay healthy [7, 8].

The built environment is a broad term that encompasses the man-made physical elements of the environment such as homes, buildings, streets, open spaces, and infrastructure, which could have an impact on the physical and mental levels of the person and the health of a community [9].

Research on the association between built environment and health has increased in recent years; Smith et al. reported that improving neighborhood walkability and quality of green areas and providing adequate active transport infrastructure are likely to generate positive impacts on activity in children and adults [10]; on the other hand, Nowak et al. reported that a poor-quality built environment is related to negative birth outcomes [11].

Studies about the relationship between built environments and mental health have reported that a state of well-being, response to stressors, the ability to work productively, and to make contributions to the community all can be affected by factors such as the quality of public utilities, walking distance to public spaces, access to transport, and level of infrastructure [8, 12–17]. Generaal et al. reported through analysis across eight Dutch cohort studies that urbanization is associated with depression, indicating that a wide range of environmental aspects may relate to poor mental health [18].

This overview aims to collect, summarize, critically assess, and interpret the evidence related to the systematic reviews (SRs) of the built environment on mental health.

2. Methods

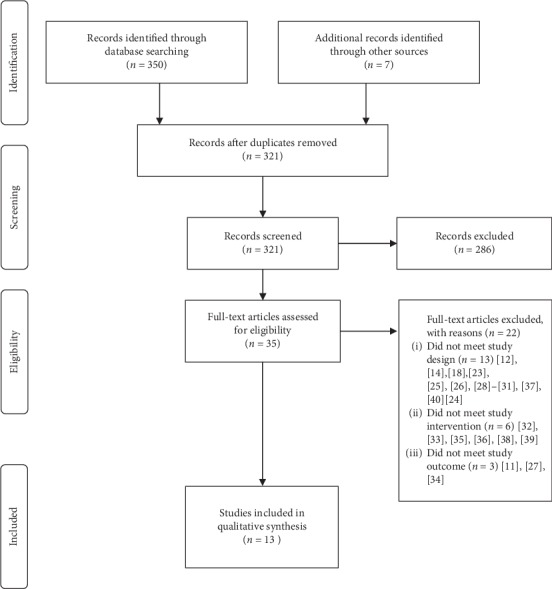

We conducted an overview that evaluated the adequate process and quality of SRs of built environment interventions and their effects on mental health status. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic review protocol (registration number: CRD42018102676), and we reported the overview according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19] ().

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The overview included any systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses that reported a structured quality evaluation of included studies, as well as SRs published in peer-reviewed, scientific journals. Inclusion criteria were organized following the patient, intervention/exposition, comparison, and outcome (PI/ECO) reporting structure. Participants (P) included the entire population (without restrictions). Intervention/exposition (I/E) included the built environment, as defined by the National Library of Medicine's controlled vocabulary thesaurus (MESH), described above [9]. Comparisons (C) were not specified for the purpose of the inclusion criteria of the overview of SRs, but comparators reported in the original SRs were considered in the analysis. Outcomes (O) included mental health, as defined by the National Library of Medicine's controlled vocabulary thesaurus (MESH), described above [1]. We excluded SRs that do not include primary studies and SRs with outcomes not related to mental health.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy was designed to identify all existing published systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Search terms were formulated using the PICO structure. A systematic literature review was conducted by searching the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, MEDLINE (OVID 1946 to present), LILACS, and PsycINFO, published in English and Spanish. We ran the most recent search on November 2019. We reviewed references of all included articles in order to identify additional studies.

The complete search strategy is shown in Supplementary Material S2. The search results were imported into Rayyan [20], an online tool that provides procedural support in the selection of articles for systematic reviews.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy against inclusion and exclusion criteria, and when eligibility was determined, we read the full text. Discrepancies around inclusion were resolved by discussion or in consultation with a third author when required. We searched the reference lists of all included reviews to identify any further relevant reviews. Citations were downloaded and managed in Mendeley.

Two authors independently extracted data from each SR into a purpose-built, predesigned, structured template. The data extraction forms were then summarized in a table and reviewed independently by a third reviewer.

2.4. Assessment of Methodological Quality

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the included SRs using the Assessing Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews-2 tool (AMSTAR-2) [21]. Each question in the AMSTAR-2 tool is answered as either “yes,” “partial yes,” “no,” “can't answer,” or “unable to assess”. Overall confidence in the quality rating in the SRs was classified as high, moderate, low, or critically low depending on the presence of critical and noncritical flaws in items 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 [21]. We resolved any disagreements via a consensus decision by a third reviewer. Interobserver agreement was assessed with the kappa coefficient for each item and the total AMSTAR-2 score.

We categorized conclusions reported by authors for each SR, into six categories: “inconclusive,” “no effect,” “probably harmful,” “harmful,” “probably beneficial,” and “beneficial” (see Table 1 for further details of the category definition). Two reviewers independently categorized the conclusions. Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. In all cases, judgement represented a formal assessment about the evidence, benefits, and harms of each intervention.

Table 1.

Classification of the conclusions according to the results reported by authors.

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Unclear | The direction of results differed within reviews due to conflicting results or limitations of individual studies |

| No effect | The conclusions provided evidence of no difference between intervention and comparator |

| Probably harmful | The conclusions did not claim for firm harmful effect despite the reported negative treatment effect |

| Harmful | The conclusions were reported as clearly indicative of a harmful effect |

| Probably beneficial | The conclusions did not claim for firm benefits despite the reported positive treatment effect |

| Beneficial | The conclusions reported a clear beneficial effect without major concerns regarding the supporting evidence |

2.5. Data Analysis and Narrative Synthesis

We presented our findings through tables to describe the characteristics of the included SRs. The outcome components were listed, followed by a narrative synthesis that included understanding components of the interventions, exploring patterns of findings across studies, and giving greater weight to studies of higher quality in the interpretation of the findings, especially if there were contradictions between the findings of reviews.

Additionally, to analyze the overlap of included SRs, we used a citation matrix that crosslinks the SRs with their included primary studies to calculate the “corrected covered area” (CCA). Based on the reported of CCA value, we classified into four categories: slight (0–5%), moderate (6–10%), high (11–15%), and very high (>15%) overlap [22].

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Results

We identified 350 records from the search strategies updated until November 2019 and seven more from the references of the included studies. After removing duplicates, 321 were manually screened, and 286 records were excluded for title and abstract. We reviewed the full text of 35 studies, 24 of which were excluded [11, 12, 14, 18, 23–42]. Finally, eleven SRs were included in the narrative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search and study selection.

3.2. Characteristics and Quality of the Systematic Reviews

Included SRs were published between 2010 and 2019, and they comprised studies conducted between 1991 and 2017. The last search was conducted in September 2017 [43]. One out of eleven included SRs performed a meta-analysis of data. Table 2 describes the main characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included systematic reviews.

| Author (Year) | Population/stage | Number of included studies∗ | Interventions | Outcome | Meta-analysis | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowler et al. 2010 [44] | All ages | 11studies (6 crossover trial, 1 observational study, 4 pretest-posttest comparison groups-randomised) | Exposure to natural environments: (i) Public parks (ii) Green university campuses |

Well-being (i) Anger (ii) Fatigue (iii) Sadness (iv) Anxiety (v) Anger |

Yes | Methodology quality checklist was devised by the authors |

| Friesinger et al. 2019 [43] | People with mental health problems | 11 studies (6 cross-sectional, 1 longitudinal, 1mixed-method, 1participant observation-free analysis, 1 interview content analysis, and 1 photo-elicitation and interviews) | Housing type | Well-being | No | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2017) |

| Gascon et al.2015 [45] | General population—all ages | 28 studies (21 cross-sectional, 6 longitudinal, and 1 ecological study) | Residential green and blue spaces | Mental health | No | Quality score was based on 11 different items |

| Gascon et al.2017 [46] | General population—all ages | 12 studies (7 cross-sectional, 4 longitudinal, and 1 pre/postobservational study) | Outdoor blue spaces | Mental health and well-being | No | Quality score was based on 11 different items |

| Gong et al 2016 [47] | General population—all ages | 11 studies (11 cross-sectional) | Urban environment: (i) Architectural design (ii) Land use (iii) Walkability, connectivity, and accessibility (iv) Neighborhood and housing quality |

Psychological distress (i) Depression (ii) Anxiety |

No | Critical appraisal proforma developed and validated by the Health Evidence Bulletin Wales project |

| Ige et al.2018 [48] | General population—all ages | 6 studies (1 randomised controlled trial, 1 quasiexperimental study, 1 before-and-after studies, 2 longitudinal, and 1 case-control) | Buildings: (i) Quality of housing (thermal and ventilation) (ii) Housing affordability/access to affordable homes or social housing |

(i) Mental health (ii) Well-being |

No | Quality assessment tool developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) |

| Moore et al.2018 [49] | General population in high-income countries | 10 studies (5 longitudinal and 5 cross-sectional) | Built environment: (i) Transport infrastructure modifications (ii) Improving green infrastructure (iii) Urban regeneration |

(i) Mental health (ii) Well-being |

No | Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 2.0) and risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) |

| Rautio et al.2017 [15] | General population—all ages | 57 studies (1 controlled trial, 40 cross-sectional, 9 longitudinal, 1 multicohort, 1 ecologic design, and five cross-sectional and longitudinal) | Living environment: (i) House and built environment (ii) Green spaces (iii) Noise and air pollution |

Depression | No | Downs and Black checklist modified by the authors |

| Turley et al.2013 [50] | Slums—adults/children | 1 study (1 controlled study with only postintervention data) | Cement floors (Piso Firme) | (i) Depression (ii) Stress |

No | NICE/GATE tool |

| van den Berg et al.2015 [51] | General population—adults | 19 studies (15 cross-sectional and 4 longitudinal) | Green spaces: (i) Amount of green space around the residence in circular buffer (ii) Amount of green space in small area/neighborhood (iii) Presence/number of green spaces within distance (iv) Having a garden (v) Distance to nearest green space (vi) Amount of green space around the residence in circular buffer |

Mental health | No | Methodological quality criteria list |

| Zhang et al. 2017 [52] | People with mobility impairments | 12 studies (2 cross-sectional analytical, 2 randomized controlled trials, 1 quantitative descriptive study, 1 nonrandomized controlled trial, 4 phenomenology, and 2 qualitative description) | Health-promoting nature access: (i) Surrounding nature of nursing homes (ii) Green environment near retirement homes (iii) Outdoor blue and green spaces |

Mental health | No | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) |

∗Articles included in the RS with the outcome mental health.

The quality of the included SRs according to AMSTAR-2 scores was categorized as “high” in two SRs [49, 50] and as “critically low” in nine SRs [15, 43–48, 51, 52] (Table 3). Drawbacks in the critical items included: the SRs did not state prior design or registered protocol [15, 43, 45–48, 51, 52], did not include list of excluded studies with reasons [15, 43–48, 51, 52], and did not address the risk of bias in the individual studies [15, 43–45, 47, 52]. Drawbacks in the noncritical items included: the authors did not report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the SRs [15, 43–52], and the SRs did not report conflicts of interest [43, 47]. The kappa coefficient for the total AMSTAR-2 score showed substantial agreement (0.78; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67–0.88).

Table 3.

Assessing Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) tool for the assessment of multiple systematic reviews and financial sources of support.

| Author (year) | Overall confidence | Financial sources of support |

|---|---|---|

| Bowler et al. [44] | Critically low | Natural England Contract FST20-84-037 to ASP |

| Friesinger et al. [43] | Critically low | No report |

| Gascon 2015 et al. [45] | Critically low | CERCA Institutes Integration Program (SUMA 2013) |

| Gascon 2017 et al. [46] | Critically low | European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 666773 |

| Gong et al. [47] | Critically low | No report |

| Ige et al. [48] | Critically low | Wellcome Trust through the Wellcome Trust Sustaining Health Award (Award number: 106857/Z/15/Z) |

| Moore et al. [49] | High | (MR/KO232331/1) from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government, and the Wellcome Trust |

| Rautio et al. [15] | Critically low | Academy of Finland (268336), European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (under grant agreement no. 633595) for the DynaHEALTH action and by the European Commission (Grant LifeCycle—H2020—733206) |

| Turley et al. [50] | High | Internal sources: no sources of support supplied |

| External sources: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie), UK; Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Advanced Study, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth), Australia | ||

| van den Berg et al. [51] | Critically low | European Commission as part of the7th Framework project “Positive health effects of natural environment for human health and well-being (PHENOTYPE)” (grant agreement no. 282996) |

| Zhang et al. [52] | Critically low | Danish Nature Agency, Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark (grant number: NST-843.00021), the Bevica Foundation (grant number: 2015–7018), 15. Juni Fonden (grant number: 2015-A-66), and the Danish Outdoor Council (grant number: 104052) |

3.2.1. Mental Health and Well-Being

Bowler et al.'s review found that natural environments, when compared to synthetic environments, might have direct and positive impacts on well-being such as anger (Hedges' g = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.23, 0.69), fatigue (Hedges' g = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.76), and sadness (Hedges' g = 0.36; 95% CI = 0.08, 0.63) [44]. Gascon 2017 et al.'s review suggested a positive association between exposure to outdoor blue spaces and mental health and well-being; however, the evidence of any direct causation was limited [46].

Ige et al.'s review suggests that affordable housing of good quality, with good energy efficiency and adequate ventilation, has the potential to be an important contributor to improved well-being [48]. Friesinger et al.'s review indicated that well-being was more likely to be linked to community and neighbourhood qualities than to a specific building, while deterioration in the physical quality of the neighbourhood exacerbated mental health problems [43].

van den Berg et al.'s review found that adults who live in green neighbourhoods report better mental health than adults who live in less green neighbourhoods, especially in population groups with lower socioeconomic status [51]. Zhang et al.'s review reported that people with mobility disabilities could gain mental health benefits and social health benefits from nature in different kinds of nature contacts ranging from passive contact, active involvement to rehabilitative interventions [52].

Gascon 2015 et al.'s review found limited evidence of the benefits of long-term residential surrounding greenness and mental health in adults, whereas the evidence was inadequate in children. Finally, Moore et al.'s review reported that the evidence for the impact of built environment interventions on mental health and well-being is weak, as the primary studies reported a very small or no effect of the built environment on mental health and well-being [45].

The CCA of 2.5% indicates a slight overlap of primary studies between the different SRs.

3.2.2. Depression and Stress

Rautio et al.'s review reported that poor housing quality and nonfunctioning, lack of green areas, and noise and air pollution are more clearly related to depressive mood.

Turley et al.'s review included only one study which observed fewer symptoms of maternal depression and maternal stress in intervention households provided with cement floors as part of the “Piso Firme” project; however, there was no evidence available to assess the impact of slum upgrading on depression and stress.

The CCA of 0% indicates a slight overlap of primary studies between the different SRs.

3.2.3. Psychological Distress

Gong et al.'s review suggested that some aspects of the urban environment including housing with deck access, neighbourhood quality, the amount of green space, land-use mix, industry activity, and traffic volume have significant associations with psychological distress.

According to the conclusions of the SRs reported by the authors, only one SR reported a “beneficial” effect on mental health and well-being outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Conclusions according to the outcome reported by authors.

| Outcomes | Conclusions reported by authors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unclear | No effect | Probably harmful | Harmful | Probably beneficial | Beneficial | |

| Mental health and well-being | Gascon 2015 et al. [45] | Moore et al. [49] | NA | NA | Gascon 2017 et al. [46] | Bowler et al. [44] |

| Ige et al. [48] | ||||||

| van den Berg et al. [51] | ||||||

| Zhang et al. [52] | ||||||

| Friesinger et al. [43] | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Depression and stress | Turley et al. [50] | NA | NA | NA | Rautio et al. [15] | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Psychological distress | NA | NA | NA | NA | Gong et al. [47] | NA |

4. Discussion

Our overview collected information from eleven SRs published between 2010 and 2019 and included 178 primary studies (63% of them were cross-sectional). Eight SRs evaluated the mental health and well-being, and only one SR reported “high-quality” assessment; however, the authors concluded that the interventions had “no effect” [49]; two SRs evaluated depression and stress and one SR reported “high-quality” assessment; the authors concluded that the interventions would be “unclear” effect [50]; only one SR evaluated psychological distress and reported “critically low-quality” assessment, and the authors concluded that the effect of the interventions would be “probably beneficial” effect [47].

We found a slight overlap (2.5%) of primary studies between the different SRs looking at the outcomes of mental health/well-being and depression/stress. Only one of the included systematic reviews performed a meta-analysis [44], heterogeneity due to the design of primary studies, weak methodological rigor, and the lack of standardized tools that assess mental health, and built environments are the main drawbacks reported by the others SRs.

The research looking at the role of the built environment on mental health is relatively new, and causal pathways connecting both constructs are just starting to emerge. According to van den Bosch et al., mental health is consistently influenced directly or indirectly by multiple environmental exposures, and depressive mood may be the result of the rapid urbanization and a disconnection from our evolutionary origin and natural environments [53]. Frank et al. emphasize transportation infrastructure, land use, the pedestrian environment, and greenspace influence people's behavior and exposures [54]. Some of these, such as social cohesion, are directly related to mental health. While others may have an indirect effect, past research has suggested that green space could modulate the impact of stressors [55]. Similarly, the built environment plays a role in the perception of safety and the enjoyment of aesthetics and, as such, can impact the individual's mental health [56].

The high number of primary studies in the last 10 years reflects the increasing interest by the researchers and public health professionals in this area; however, a major limitation of this evidence is more than 50% of the included studies were cross-sectional; in these studies, the temporal relationship between exposure and outcome cannot be established [51]; therefore, it is not possible to conclude the causality of the built environment on mental health [47]. Hence, as mentioned in some SRs [48, 49, 52], there is a need for more high-quality research, especially controlled longitudinal/time-series analyses.

Regarding the effect assessment postintervention, we could not possibly assess whether the short- or long-term effects of the interventions are maintained, continue to improve, or worsen over time because none of the reviews reported this information.

To our knowledge, this is the first overview of systematic reviews rigorously looking at the relationship between the built environment and mental health. Clark and colleagues sought to do so in 2007; their review included mostly primary research studies—only three 3 out of 99 reviewed references were systematic reviews—leading them to conclude a “lack of robust research, and of longitudinal [studies] in many areas” [49]. Nearly thirteen years after they ran their search, systematic reviews have gone from three to eleven, integrating new specific outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. However, heterogeneity is still a major issue when assessing the impact of built environments on mental health [57].

Two government-sponsored scoping reviews from Canada and the UK were published in 2013 and 2018, respectively [58, 59]. The former studies the impact of housing circumstances and housing interventions in mental health while the latter explores the impact of natural environments. Because Johnson's review relies on evidence “relevant to public policy considerations and to the UK context,” his findings cannot easily be applied to the general population. Coghill et al., on the other hand, used a systematic approach to evidence synthesis but chose to focus exclusively on evidence related to natural environments published in 2012 or later.

While their findings are similar to ours, they chose a positive framing when writing their final conclusions and recommendations. On a final note, their review signaled several limitations that were identified by our team, making evident the need for an interdisciplinary approach similar to that put forward by Weaver and colleagues for physical health.

Interdisciplinary research between urban planning, architecture, psychology, environmental health, epidemiology, and sociology is crucial to fully grasp the pathways from the built environment to mental health [25]. The most salient dimensions of the built environment and contextual factors should be incorporated into more ecologically valid models [60].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Overview

This overview evaluated the available evidence of the mental health outcome, which is considered a priority in public health, and this makes our overview relevant to current policymakers and stakeholders to adequately develop strategies to strengthen health promotion policies. We followed a rigorous systematic review method and reported according to PRISMA guidelines [19]. We did not limit our search by publication year; also, to limit bias, data selection, extraction, and assessment of methodological quality were performed by two people independently. The interrater agreement was excellent. Limitations of this overview include the use of a search filter limited to only systematic review matches, as well as the searches being limited to publications in English and Spanish, and this may have resulted in some studies being missed. We were also limited by the broad scope of our exposure, “the built environment” can range from small interventions indoors to big urban expansions outdoors in both urban and rural settings. As such, we did not aim to identify specific interventions but to measure the overall quality of the existing literature, as appraised by other authors. Finally, we could not account for mediators between the built environment and health such as noise, physical activity, social cohesion, temperature, or air pollution as this was outside the scope of our overview.

5. Conclusions

There was insufficient evidence available to make firm conclusions on the effects of built environment interventions on mental health outcomes (well-being, depression and stress, and psychological distress). The evidence collected reported high heterogeneity (outcomes and measures) and the high- to critically low-quality assessment. Future research efforts in the field should focus on improved methodological design to reduce the risk of bias and improved reporting through standardized tools that evaluate the different interventions and outcomes, as well as interdisciplinary research involving professionals specialized in mental health, public health, spatial planners, and urban design experts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Universidad UTE.

Additional Points

Differences between Protocol and Review. We changed the title registered in PROSPERO: Environmental and architectural interventions and their effects on mental health: a systematic review of reviews to Overview of “systematic reviews” of the built environment's effects on mental health. To further increase the coverage of the literature searches, one additional bibliographic database was searched for the review—PsycINFO. We update the search (November 2019). Additionally, while it is common to encounter an overlap of primary studies when producing an overview of systematic review, we calculated the “corrected covered area” (CCA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material file includes Tables S1 (PRISMA 2009 checklist) and S2 (Search strategy).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Promoting mental health concepts emerging evidence practice summary report. 2004. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/promoting_mhh.pdf.

- 2.World Health Organization. The world health report: mental health: new understanding, new hope. 2001. https://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/whr01_en.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.World Health Organization. mhGAP operations manual mental health gap action programme. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275386/9789241514811-eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 4.Vigo D., Thornicroft G., Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. The Lancet. 2007;370(9594):1241–1252. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom D. E., Cafeiro E. T., Jané-Llopis E., et al. The global economic burden of non-communicable diseases. 2011. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Harvard_HE_GlobalEconomicBurdenNonCommunicableDiseases_2011.pdf.

- 7.Organización Mundial de la Salud. Plan de acciόn sobre salud mental 2013-2020. 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97488/9789243506029_spa.pdf?sequence=1.

- 8.Shen Y. Community building and mental health in mid-life and older life: evidence from China. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;107:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medical Subject Headings. Built environment. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=built+environment.

- 10.Smith M., Hosking J., Woodward A., et al. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport–an update and new findings on health equity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017;14(1):p. 158. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0613-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nowak A. L., Giurgescu C. The built environment and birth outcomes. MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2017;42(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/nmc.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Bosch M., Sang A. O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health—a systematic review of reviews. Environmental Research. 2017;158(2016):373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyer K., Kaltenbach A., Szabo A., Bogar S., Nieto F., Malecki K. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11(3):3453–3472. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormick R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: a systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2017;37:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rautio N., Filatova S., Lehtiniemi H., Miettunen J. Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: a systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2018;64(1):92–103. doi: 10.1177/0020764017744582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melis G., Gelormino E., Marra G., Ferracin E., Costa G. The effects of the urban built environment on mental health: a cohort study in a large northern Italian city. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12(11):14898–14915. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121114898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evered E. The role of the urban landscape in restoring mental health in Sheffield, UK: service user perspectives. Landscape Research. 2016;41(6):678–694. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2016.1197488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Generaal E., Hoogendijk E. O., Stam M., et al. Neighbourhood characteristics and prevalence and severity of depression: pooled analysis of eight Dutch cohort studies. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;215(2):468–475. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):p. 210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shea B. J., Reeves B. C., Wells G., et al. Amstar 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:p. 4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieper D., Antoine S.-L., Mathes T., Neugebauer E. A. M., Eikermann M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(4):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee A. C. K., Maheswaran R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. Journal of Public Health. 2011;33(2):212–222. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tully Mark A., Kee F., Foster C., Cardwell Chris R., Weightman Alison L., Cupples Margaret E. Built environment interventions for increasing physical activity in adults and children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd010330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruebner O., Rapp M. A., Adli M., Kluge U., Galea S., Heinz A. Cities and mental health. Deutsches Aerzteblatt International. 2017;114(8):121–127. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark C., Myron R., Stansfeld S., Candy B. A systematic review of the evidence on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health. Journal of Public Mental Health. 2007;6(2):14–27. doi: 10.1108/17465729200700011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran M., Van Cauwenberg J., Hercky-Linnewiel R., Cerin E., Deforche B., Plaut P. Understanding the relationships between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review of qualitative studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2014;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sallis J. F., et al. Co-benefits of designing communities for active living: an exploration of literature. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0188-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richter D., Hoffmann H. Architektur und Design psychiatrischer Einrichtungen. Psychiatrische Praxis. 2014;41(3):128–134. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fricke O. P., Halswick D., Langler A. Healing architecture for sick kids: concepts of environmental and architectural factors in child and adolescent psychiatry. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2019;47(1):27–33. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seppänen A., Törmänen I., Shaw C., Kennedy H. Modern forensic psychiatric hospital design: clinical, legal and structural aspects. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2018;12(1):p. 58. doi: 10.1186/s13033-018-0238-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone G. A., Fernandez M., DeSantiago A. Rural latino health and the built environment: a systematic review. Ethnicity & Health. 2019:1–26. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2019.1606899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Britton E., Kindermann G., Domegan C., Carlin C. Blue care: a systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promotion International. 2018;35(1):50–69. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jovanović N., Campbell J., Priebe S. How to design psychiatric facilities to foster positive social interaction –a systematic review. European Psychiatry. 2019;60:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiland T., Ivory S., Hutton J. Managing acute behavioural disturbances in the emergency department using the environment, policies and practices: a systematic review. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;18(4):647–661. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.4.33411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayes S. L., Mann M. K., Morgan F. M., Kelly M. J., Weightman A. L. Collaboration between local health and local government agencies for health improvement. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;10(6):p. CD007825. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007825.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garin N., Olaya B., Miret M., et al. Built environment and elderly population health: a comprehensive literature review. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2014;10(1):103–115. doi: 10.2174/1745017901410010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drahota A., Stores R., Ward D., Galloway E., Higgins B., Dean T. P. Sensory environment on health-related outcomes of hospital patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd005315.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooklin A., Joss N., Husser E., Oldenburg B. Integrated approaches to occupational health and safety: a systematic review. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2017;31(5):401–412. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.141027-lit-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D. Blues from the neighborhood? neighborhood characteristics and depression. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30(1):101–117. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valson J. S., Kutty V. R. Gender differences in the relationship between built environment and non-communicable diseases: a systematic review. Journal of Public Health Research. 2018;7(1):43–49. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2018.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanaken G.-J., Danckaerts M. Impact of green space exposure on children’s and adolescents’ mental health: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(12) doi: 10.3390/ijerph15122668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friesinger J. G., Topor A., Bøe T. D., Larsen I. B. Studies regarding supported housing and the built environment for people with mental health problems: A mixed-methods literature review. Health & Place. 2019;57:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bowler D. E., Buyung-Ali L. M., Knight T. M., et al. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):p. 456. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gascon M., Triguero-Mas M., Martínez D., et al. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12(4):4354–4379. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120404354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gascon M., Zijlema W., Vert C., White M. P., Nieuwenhuijsen M. J. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: a systematic review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2017;220(8):1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gong Y., Palmer S., Gallacher J., Marsden T., Fone D. A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environment International. 2016;96:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ige J., Pilkington P., Orme J., et al. The relationship between buildings and health: a systematic review. Journal of Public Health. 41(2):121–132. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore T. H. M., Kesten J. M., López-López J. A., et al. The effects of changes to the built environment on the mental health and well-being of adults: systematic review. Health & Place. 2018;53(2017):237–257. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turley R., et al. Slum upgrading strategies involving physical environment and infrastructure interventions and their effects on health and socio-economic. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd010067.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van den Berg M., Wendel-Vos W., van Poppel M., Kemper H., van Mechelen W., Maas J. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2015;14(4):806–816. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang G., Poulsen D. V., Lygum V. L., Corazon S. S., Gramkow M. C., Stigsdotter U. K. Health-promoting nature access for people with mobility impairments: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017;14(7) doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van den Bosch M., Meyer-Lindenberg A. Environmental exposures and depression: biological mechanisms and epidemiological evidence. Annual Review of Public Health. 2019;40(1):239–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frank L. D., Iroz-Elardo N., MacLeod K. E., Hong A. Pathways from built environment to health: a conceptual framework linking behavior and exposure-based impacts. Journal of Transport & Health. 2019;12:319–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2018.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dzhambov A. M., Markevych I., Lercher P. Greenspace seems protective of both high and low blood pressure among residents of an Alpine valley. Environment International. 2018;121:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Picavet H. S. J., Milder I., Kruize H., de Vries S., Hermans T., Wendel-Vos W. Greener living environment healthier people? Preventive Medicine. 2016;89:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weaver N., et al. Taking STOX: developing a cross disciplinary methodology for systematic reviews of research on the built environment and the health of the public. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. Jan. 2002;56(1):48–55. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson R. Pervasive interactions: a purposive best evidence review with methodological observations on the impact of housing circumstances and housing interventions on adult mental health and well‐being. Housing, Care Support. 2013;16(1):32–49. doi: 10.1108/14608791311310546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coghill C.-L., et al. Characteristics of natural environments associated with mental health and well-being. 2018. https://www.swpublichealth.ca/sites/default/files/file-attachments/reports/ph201809_characteristics_of_natural_environments_associated_with_mental_health_and_well-being.pdf.

- 60.Evans G. W. The built environment and mental health. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2003;80(4):536–555. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material file includes Tables S1 (PRISMA 2009 checklist) and S2 (Search strategy).