Abstract

The novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) epidemic has brought serious social psychological impact to the Chinese people, especially those quarantined and thus with limited access to face-to-face communication and traditional social psychological interventions. To better deal with the urgent psychological problems of people involved in the COVID-19 epidemic, we developed a new psychological crisis intervention model by utilizing internet technology. This new model, one of West China Hospital, integrates physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers into Internet platforms to carry out psychological intervention to patients, their families and medical staff. We hope this model will make a sound basis for developing a more comprehensive psychological crisis intervention response system that is applicable for urgent social and psychological problems.

Keywords: novel coronavirus, COVID-19, psychological crisis intervention, mental health

Since December 2019, Wuhan and gradually other places of China have experienced an outbreak of pneumonia epidemic caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV, later named SARS-CoV-2).1 The World Health Organization has declared the current outbreak of COVID-19 in China as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. As of 10:00 Feb 13, 2020, the epidemic has caused 1366 deaths out of 59 834 confirmed and 16 067 suspected cases.2 Some unprecedented measures were taken to stop the spread of the virus including cancelling of gatherings, extending the Chinese New Year holidays, and limiting the number of people in public places (e.g. train stations and airports). The outbreak itself and the control measures may lead to widespread fear and panic, especially stigmatization and social exclusion of confirmed patients, survivors and relations, which may escalate into further negative psychological reactions including adjustment disorder and depression.3–5

Sudden outbreaks of public health events always pose huge challenges to the mental health service system. Examples include the HIV/AIDS epidemic that captivated world attention in the 1980s and 1990s, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002 and 2003, the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009, the Ebola virus outbreak in 2013, and the Zika virus outbreak in 2016.6 During these epidemics, the consequences on the psychosocial wellbeing of at-risk communities are sometimes largely overlooked, especially in the Ebola-affected regions, where few measures were taken to address the mental health needs of confirmed patients, their families, medical staffs or general population.7 The absence of mental health and psychosocial support systems and the lack of well-trained psychiatrists and/or psychologists in these regions increased the risks of psychological distress and progression to psychopathology.8 The lack of effective mental health systems added to the poverty in Sierra Leone and Liberia.9

In China, the mental health service system has been greatly improved after several major disasters, especially the Wenchuan earthquake. In the process of dealing with group crisis intervention, various forms of psychosocial intervention services have been developed, including the intervention model of expert-coach-teacher collaboration after the Wenchuan earthquake10 and the equilibrium psychological intervention on people injured in the disaster incident after the Lushan earthquake.11 With the support for remote psychological intervention provided by the development of Internet technology, especially the widespread application of 4G or 5G networks and smartphones, we developed a new intervention model to handle the present COVID-19 public health event. This new model, one of West China Hospital, integrates physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers into Internet platforms.

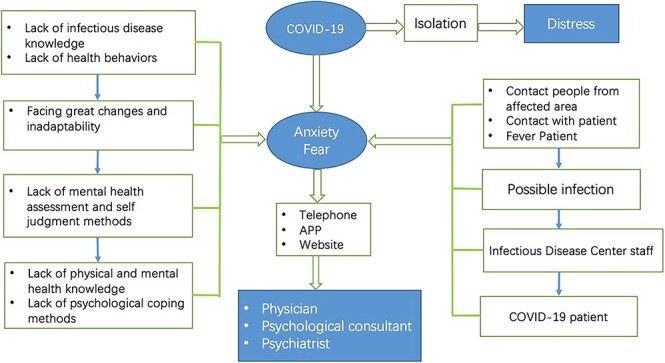

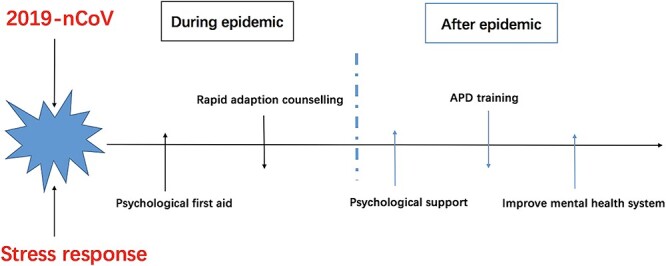

We propose that the psychological crisis intervention should be dynamic, adapted to suit different stages of the epidemic, i.e., during and after the outbreak. During the outbreak, mental health professionals should actively participate in the overall intervention process for the disease, so that the mental health and psychosocial response can be mobilized in a timely fashion.12 Specifically, psychological crisis interventions should be integrated into the treatment of pneumonia and blocking of the transmission routes. In this stage, psychological crisis intervention should include two simultaneous activities: (1) intervention for fear of disease, carried out mainly by physicians and assisted by psychologists; (2) intervention for difficulty in adaptation, mainly by social psychologists. Among them serious mental problems (e.g. violence, suicide behaviors) must be managed by psychiatrists. Such emotion hypothetical model of psychological crisis intervention is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 .

The emotion hypothetical model of psychological crisis intervention in COVID-19 epidemic.

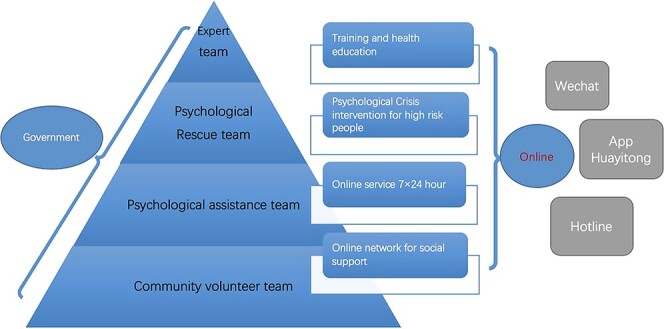

During the epidemic, rapid integration of the gov-ernment and social forces into the Internet framework can maximize effective management of the psychological crisis. We established a pyramid structure of psychological crisis management with government as the core leader. At the bottom of the pyramid are communities, which mainly provide psychosocial support. Psychological assistance (such as hotline, online consulting) is used to identify and help the target groups who need intervention. Through the Huayitong app and Psyclub applet (two integrated APPs for online registration, appointment, payment and other functions for West China Hospital and Sichuan psychological consultant platform), telephone hotline and WeChat platform, we quickly organized physicians at all levels of the West China Hospital (including retired professors) and psychologists from all over Sichuan Province to form psychological rescue teams to formulate solutions (e.g. developing technical guidelines and training programs, starting online consultation and setting up problem feedback mechanisms). Psychological rescue teams conduct crisis interventions for confirmed patients and front-line staff. The expert team at the top of the pyramid provide health education and training during the whole process (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 .

Network tools and organization framework of psychological crisis management for COVID-19 epidemic.

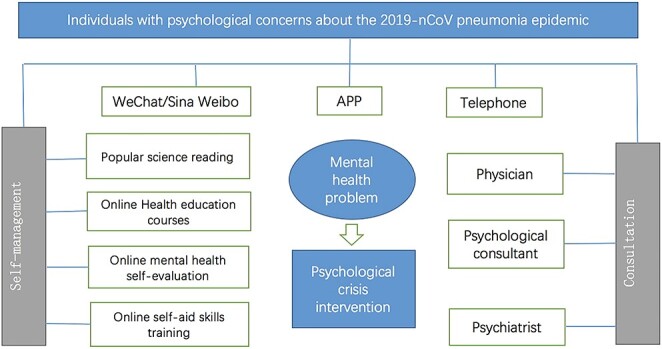

How to quickly identify the emotional and stress problems of individuals is an important part of basis for psychological intervention. We screened the mental health status of suspected cases, medical staffs and general population via WeChat platform and/or telephone by using questionnaires (e.g. Mood Index Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionaire-9) as the evaluation tool.13,14 Proper intervention strategies were chosen based on the screening results. Follow-up is performed regardless of whether the individual reports mental health problems or not. The process and content of psychological intervention is shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1.

Figure 3 .

Online psychological intervention methods for COVID-19 epidemic.

Table 1 .

Work list of online Psychological interventions.

| Online service | Technical guidance | Problem feedback mechanism | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service content | Service platform | ||||

| • Knowledge about prevention and control of the novel coronavirus⮚ How to wear a mask properly?⮚ How to protect yourself when you go out: five protective measures recommended.⮚ How to deal with information explosion related to virus epidemic | • Knowledge about self-psychological adjustment skills⮚ Maintain emotional stability: an abdominal breathing relaxation method.⮚ How to face the anxiety and fear resulted by the novel coronavirus: advices from West China Hospital experts⮚ Audio of mindfulness-based stress reduction | • Hotline service: 9:00 am-9:00 pm• Online consulting: 9:00 am-9:00 pm• Online assessment: 7×24 h⮚ General anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7)⮚ Mood Index Questionnaire⮚ Patient Health Questionnaire-9⮚ Pittsburgh sleep quality index | • WeChat official account of West China Hospital, Sichuan University• Sina Weibo official account of West China Hospital, Sichuan University• WeChat official account of West China Hospital Mental Health Center• Sina Weibo official account of West China Hospital Health Center• APP: Huayitong• WeChat applet: Psyclub | • E-book: Handbook for mass psychological protection against the zoonotic 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)• E-book: For the online prevention and control of the zoonotic 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Huaxi model | • Working group: summarize and report daily work everyday• Psychological specialist training supervision group for relevant trainings |

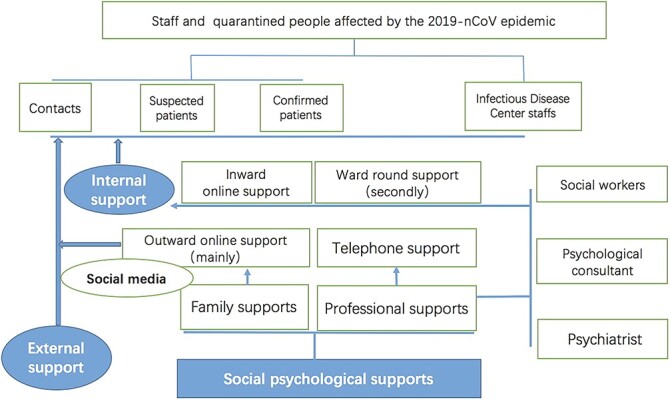

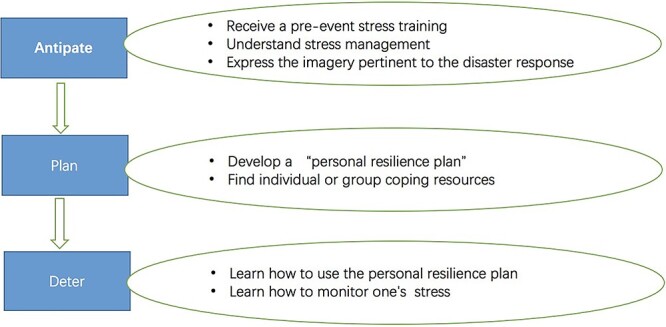

After the epidemic outbreak, psychosocial support mainly focuses on the quarantined people and medical staffs working for them (Fig. 4). Social support and psychological intervention are mostly provided by family members, social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists to isolated patients, suspected patients, and close contacts, primarily through telephone hotline and Internet (e.g. WeChat, APPs). Medical staffs working for the quarantined are the special group who need a lot of social support, and they are also an important force to provide social support for the isolated patients. To guarantee their continued effective work, their mental health status should be monitored and a continuum of timely interventions should be made available to support them. The Anticipated, Plan and Deter (APD) Responder Risk and Resilience Model (Fig. 5) is an effective method for understanding and managing psychological impacts among medical staffs, including managing the full risk and resilience in the responder “hazard specific” stress.15

Figure 4 .

Online social psychological support for quarantined population and staff.

Figure 5 .

The process of Anticipate, Plan and Deter (APD) methods for the psychological intervention of epidemics.

In the APD process, medical staffs receive a pre-event stress training focusing on the psychosocial impact of high-casualty events on the hospital and field disaster settings. During the training, participants are given the chance to develop a “personal resilience plan”, which involves identifying and anticipating response challenges. After that they should learn to use it in real intervention response.

Based on our experience about the model of psychological intervention practicability and effectiveness, West China Hospital developed and is carrying out the psychological rehabilitation plan, namely the two-stage psychological intervention model (Fig. 6). The central idea is to integrate Internet technology to the whole process of intervention, and to combine early intervention with later rehabilitation. In order to help patients and general population in the COVID-19 epidemic, we are trying to share it with all mental health hospitals in Sichuan Province to help relieve psychological aftershock of the public emergency. However, there are still many problems with the current psychological interventions, including effective utilization of Internet resources/tools, and efficient cooperation between medical staffs and psychologists.

Figure 6 .

The two-stage model of psychological intervention for epidemics.

Acknowledgement

This paper is supported by the 13th Five-year Plan for Disciplines of Excellence,West China Hospital of Sichuan University, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants No. 81701328, 81871061, and 81371484).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: A modelling study. Lancet 2020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kinsman J. “A time of fear”: Local, national, and international responses to a large Ebola outbreak in Uganda. Global Health 2012;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mohammed A, Sheikh TL, Gidado S, et al. Psychiatric treatment of a health care worker after infection with Ebola virus in Lagos. Nigeria Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:222–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14121576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohammed A, Sheikh TL, Gidado S, et al. An evaluation of psychological distress and social support of survivors and contacts of Ebola virus disease infection and their relatives in Lagos, Nigeria: A cross sectional study--2014. BMC Public Health 2015;15:824. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging infectious diseases: Threats to human health and global stability. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003467. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bitanihirwe BK. Monitoring and managing mental health in the wake of Ebola. Commentary. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2016;52:320–2. doi: 10.4415/ann_16_03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shultz JM, Baingana F, Neria Y. The 2014 Ebola outbreak and mental health: Current status and recommended response. JAMA 2015;313:567–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shultz JM, Neria Y. Trauma signature analysis: State of the art and evolving future directions. Disaster Health 2013;1:4–8. doi: 10.4161/dish.24011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lin C, Chen Q, Tian Y. The construction and evaluation of experts-coach-teacher collaboration model as a new trauma intervention approach. (Article in Chinese). The Journal of Beijing Normal University 2018;2018:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang X, Huang X, Li X, et al. The effect of equilibrium psychological intervention in wounded patients in Lushan earthquake. (Article in Chinese). Journal of Sichuan University (Med Sci Edi) 2014;45:533–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mohammed A, Sheikh TL, Poggensee G, et al. Mental health in emergency response: Lessons from Ebola. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:955–7. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(15)00451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. January J, Chimbari MJ. Study protocol on criterion validation of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS), patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) screening tools among rural postnatal women; a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019085. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoppen TH, Morina N. The prevalence of PTSD and major depression in the global population of adult war survivors: A meta-analytically informed estimate in absolute numbers. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2019;10:1578637. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1578637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schreiber M, Cates DS, Formanski S, et al. Maximizing the resilience of healthcare workers in multi-hazard events: Lessons from the 2014-2015 Ebola response in Africa. Mil Med 2019;184:114–20. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]