The discovery of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 bridges the evolutionary gap between MERS-CoV and existing bat viruses, and suggests that bat viruses may have evolved to generate MERS-CoV through modulation of the spike protein for binding to hDPP4.

Keywords: dipeptidyl peptidase 4, Hypsugo bat, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus, spike glycoprotein

Abstract

Although bats are known to harbor Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)-related viruses, the role of bats in the evolutionary origin and pathway remains obscure. We identified a novel MERS-CoV-related betacoronavirus, Hp-BatCoV HKU25, from Chinese pipistrelle bats. Although it is closely related to MERS-CoV in most genome regions, its spike protein occupies a phylogenetic position between that of Ty-BatCoV HKU4 and Pi-BatCoV HKU5. Because Ty-BatCoV HKU4 but not Pi-BatCoV HKU5 can use the MERS-CoV receptor human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) for cell entry, we tested the ability of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 to bind and use hDPP4. The HKU25-receptor binding domain (RBD) can bind to hDPP4 protein and hDPP4-expressing cells, but it does so with lower efficiency than that of MERS-RBD. Pseudovirus assays showed that HKU25-spike can use hDPP4 for entry to hDPP4-expressing cells, although with lower efficiency than that of MERS-spike and HKU4-spike. Our findings support a bat origin of MERS-CoV and suggest that bat CoV spike proteins may have evolved in a stepwise manner for binding to hDPP4.

The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) has affected 27 countries in 4 continents with 2090 cases and a fatality rate of 34.9% since its emergence in 2012. The etiological agent, MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), belongs to Betacoronavirus lineage C [1, 2] and uses human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) as receptor for cell entry [3]. Although dromedaries are likely the immediate animal source of the epidemic [4–6], bats also harbor MERS-CoV-related viruses, which suggests a possible bat origin [7–13]. However, the evolutionary pathway and direct ancestor of MERS-CoV remains obscure. In particular, there is an evolutionary gap between MERS-CoV and related bat viruses.

Since the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, numerous novel CoVs have been discovered [14–16], with bats uncovered as an important reservoir for alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses [17–21]. When MERS-CoV was first discovered, it was most closely related to Tylonycteris bat CoV HKU4 (Ty-BatCoV HKU4) and Pipistrellus bat CoV HKU5 (Pi-BatCoV HKU5) previously discovered in the Lesser bamboo bat (Tylonycteris pachypus) and Japanese pipistrelle (Pipistrellus abramus), respectively, in Hong Kong [1, 7–10, 22]. The spike of Ty-BatCoV HKU4, but not that of Pi-BatCoV HKU5, was able to use the MERS-CoV receptor, hDPP4 or CD26, for cell entry [3, 23]. Subsequently, 3 other lineage C betacoronaviruses (Coronavirus Neoromicia/PML-PHE1/RSA/2011 [NeoCoV], BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013, and BatCoV PREDICT/PDF-2180) were also detected in vesper bats from China or Africa [11–13, 24]. A lineage C betacoronavirus, Erinaceus CoV VMC/DEU, has also been found in European hedgehogs [25]. This is interesting because hedgehogs are phylogenetically closely related to bats. The MERS-CoV can infect bat cell lines and Jamaican fruit bats [25, 26], further suggesting that bats may be the primary host of MERS-CoV ancestors.

Although NeoCoV represents the closest bat counterpart of MERS-CoV in most genome regions, its spike (S) protein is genetically divergent from that of MERS-CoV [11], suggesting an evolutionary gap between existing MERS-CoV and bat viruses and an immediate ancestor of MERS-CoV yet to be discovered. To identify the potential bat origin and understand the evolutionary path of MERS-CoV, we collected bat samples from various regions in China. Diverse CoVs were detected, including a novel lineage C betacoronavirus from Chinese pipistrelle (Hypsugo pulveratus), which can use hDPP4 for cell entry. The results support a bat origin of MERS-CoV and suggested stepwise evolution of spike protein in hDPP4 binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

Bat samples were collected by the Guangdong Institute of Applied Biological Resources (Guangzhou, China) in accordance with guidelines of Regulations for Administration of Laboratory Animals under a license from Guangdong Entomological Institute Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

Detection of Coronavirus From Bats

Samples were collected from bats captured from various locations in 7 provinces of China (Figure 1) during 2013−2015 using procedures described previously [27, 28]. Viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) extraction was performed using QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Coronavirus detection was performed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting a 440-base pair (bp) fragment of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene using conserved primers (5’-GGTTGGGACTATCCTAAGTGTGA-3’ and 5’-ACCATCATCNGANARDATCATNA-3’) as described previously [16]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with maximum likelihood method using GTR+G+I substitution model by MEGA 6.0.

Figure 1.

Map showing various sampling locations in seven provinces of China (Guangxi, Guangdong, Shanxi, Zhejiang, Yunnan, Hainan and Guizhou). Sampling locations with Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and other CoVs detected are indicated with triangle and diamond respectively.

Viral Culture

The 2 Hp-BatCoV HKU25 samples were subject to virus isolation in Vero E6 (ATCC CRL-1586), Huh-7 (JCRB0403), PK15 (ATCC CCL-33), and Rousettus lechenaultii primary kidney cells (in-house) as described previously [29].

Complete Genome Sequencing and Analysis of Hypsugo pulveratus Bat Coronavirus HKU25

Two Hp-BatCoV HKU25 complete genomes were sequenced according to our published strategy [27]. A total of 75 sets of primers, available on request, were used for PCR. The assembled genome sequences were compared with those of other CoVs using the comprehensive CoV database CoVDB (http://covdb.microbiology.hku.hk) [30]. The time of the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) was estimated based on ORF1ab sequences, using uncorrelated exponential distributed relaxed clock model in BEAST version 1.8 (http://evolve.zoo.ox.ac.uk/beast/) [31].

Cloning of Recombinant S1 Receptor-Binding Domain Proteins

The S1-RBD sequences of of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 (residues 374–604) and MERS-CoV (residues 367–606) were cloned into mammalian expression vector pCAGGS containing signal peptide (CD5) and C-terminal Fc tag from mouse IgG2a (mFc) [32, 33]. The expression plasmids were transiently transfected into human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection CRL-3216). The recombinant HKU25-RBD-mFc and MERS-RBD-mFc proteins were purified by protein A-based affinity chromatography.

Protein Binding with Flow Cytometry and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter Analysis

Huh7 (normal or DPP4 knockdown using small interfering RNA [siRNA]) or 293T (normal or transfected with DPP4-expressing plasmid) cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL MERS-RBD-mFc or 40 µg/mL HKU25-RBD-mFc at 4°C for 1 hour. Cells were then stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antimouse IgG on ice for 30 minutes. Protein-to-cell binding was analyzed using BD fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) LSRII instrument (BD Bioscience, East Rutherford, NJ).

Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

Huh7 cells were fixed on glass coverslips and incubated with 50 μg/mL HKU25-RBD-mFc or 20 µg/mL MERS-RBD-mFc in phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C for 1 hour, followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antimouse or anti-rabbit IgG. Cell nuclei were stained using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole in mounting medium. Images were acquired with 63× oil objectives using a Zeiss LSM510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope.

Knockdown of Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Expression Using Small Interfering Ribonucleic Acids

The siRNA duplexes against hDPP4 (5′-UGACAUGCCUC AGUUGUAUU-3′) were synthesized by Nucleic Acids Center at National Institute of Biological Sciences (Beijing, China), with nontargeting siRNA as negative control (Ctrl-si). Ten picomoles of siRNA were transfected into Huh7 cells with Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen). Knockdown efficiency was determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis using primers specific for hDPP4 (5′-CCTGCTTCTATGTTGATA-3′; 5′-CGAATAGTTCTGAATCCT-3′) and Western blot analysis using anti-hDPP4 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). The messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of target genes were normalized to that of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) gene [34].

Immunoprecipitation

To identify the direct interaction between MERS-RBD-mFc or HKU25-RBD-mFc and hDPP4, HEK293T cells were transfected with hDPP4-expressing plasmids and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) 48 hours after transfection. Cell lysates were incubated with purified MERS-RBD-mFc or HKU25-RBD-mFc and Dynal protein A Sepharose beads at 4°C overnight. The bound fractions of immunoprecipitates and total cell lysate (as input) were analyzed by Western blot with anti-mFc, anti-hDPP4, or anti-GAPDH antibodies.

Pseudovirus Production

Retroviruses pseudotyped with MERS-CoV, Ty-BatCoV HKU4, Pi-BatCoV HKU5, and Hy-BatCoV HKU25 S proteins were packaged by HEK293FT cells (R70007; Invitrogen). Briefly, plasmid containing the respective CoV S gene was cotransfected with a plasmid containing luciferase gene but env-defective human immunodeficiency virus-1 (pNL 4-3.Luc.RE) into 293FT cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Culture supernatant was concentrated with 5× PEG-it virus precipitation solution (SBI). For mock pseudoviruses (∆env) bearing no S protein, empty plasmid was cotransfected with pNL 4-3.Luc.RE.

Pseudovirus Cell Entry Assay

HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmid containing hDPP4 gene and empty plasmid (as mock-transfected control) by Lipofectamine 2000. Pseudoviruses bearing CoV S proteins were treated by 100 µg/mL Tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin at 37°C for 30 minutes before infection. After trypsin inactivation, pseudovirus infections were performed by spinning at 1200 ×g at 4°C for 2 hours and incubation at 37°C for 5 hours. Cells were then incubated for 72 hours and lysed for luciferase activity determination using Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). To test for inhibition of pseudovirus-mediated cell entry by anti-hDPP4 antibodies, HEK293T cells transfected with hDPP4 were preincubated with 10 µg/mL anti-hDPP4 polyclonal antibodies (R&D Systems) at 37°C for 1 hour before pseudovirus infection.

Structural Modeling of Hypsugo pulveratus Bat Coronavirus HKU25 Receptor-Binding Domain

The model of HKU25-RBD and HKU5-RBD was built with the crystal structure of MERS-RBD/hDPP4 using SWISS-MODEL with default parameters and analyzed using Discovery Studio visualizer (Accelrys, San Diego, CA), and the Ramachandran plots were examined to ensure that the structure of the models were not in any unfavorable region. The models of HKU4-RBD and HKU5-RBD were also built as positive and negative controls, respectively, with the same parameters, and were superimposed for comparison.

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The nucleotide (nt) and genome sequences of CoVs detected in this study have been lodged within GenBank under accession numbers KX442564, KX442565, and KX447541 to KX447565.

RESULTS

Detection of Coronavirus in Bats and Discovery of a Novel Lineage C Betacoronavirus From Chinese Pipistrelle

A total of 1964 alimentary samples from bats belonging to 19 different genera and 44 species were obtained from 7 provinces of China. The RT-PCR for a 440-bp fragment of RdRp gene of CoVs was positive in samples from 29 bats of 5 species belonging to 4 genera (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Sequence analysis showed that 4 samples contained alphacoronaviruses, 5 contained lineage B betacoronaviruses, and 20 contained lineage C betacoronaviruses (Supplementary Figure 1).

Of the 20 lineage C betacoronavirus sequences, 18 sequences from Tylonycteris pachypus possessed 96% nt identities to Ty-BatCoV HKU4. The other 2 lineage C betacoronavirus sequences (YD131305 and NL140462) showed ≤86% nt identities to MERS-CoV or other lineage C betacoronaviruses, suggesting a potentially novel lineage C betacoronavirus closely related to MERS-CoV (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). Both samples were collected from Chinese pipistrelle (Hypsugo pulveratus) bats, which belong to the family Vespertilionidae, captured in Guangdong Province (Figure 1). We proposed this novel CoV to be named Hypsugo pulveratus bat CoV HKU25 (Hp-BatCoV HKU25). Attempts to passage Hp-BatCoV HKU25 YD131305 and NL140462 in cell cultures were not successful.

Genome Features of Hypsugo pulveratus Bat Coronavirus HKU25

The complete genome sequences of the 2 Hp-BatCoV HKU25 strains, YD131305 and NL140462, were determined, with genome features similar to MERS-CoV including conserved ORF4a and ORF4b (Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Figure 2, and Supplementary Figure 3). They shared 95.9% overall nt identities, while possessing 82.0%, 73.2%–73.9%, 73.5%, and 69.3% nt identities to the genomes of BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013, human/camel MERS-CoVs, NeoCoV, and Ty-BatCoV HKU4, respectively. Comparison of the 7 conserved replicase domains for CoV species demarcation showed that Hp-BatCoV HKU25 represents a novel species under Betacoronavirus lineage C (Supplementary Table 5), with the concatenated sequence being most closely related to that of BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013 with 88.5% amino acid (aa) identities.

Phylogenetic and Molecular Clock Analysis

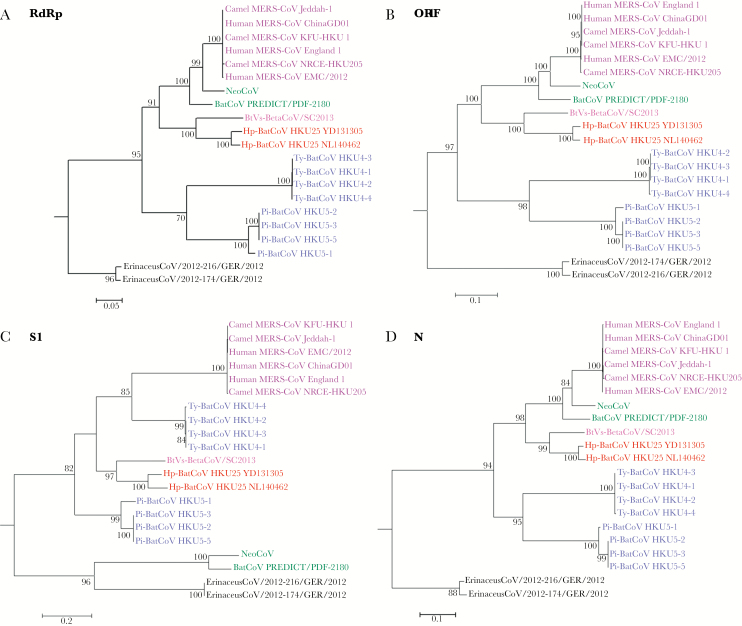

Phylogenetic trees constructed using RdRp, ORF1, S1, and N sequences of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 are shown in Figure 2. Hp-BatCoV HKU25 was most closely related to BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013, forming a distinct branch among lineage C betacoronaviruses. In RdRp, ORF1, and N genes, MERS-CoVs were most closely related to NeoCoV followed by the branch formed by Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013. In contrast, in S1 region, MERS-CoVs were most closely related to Ty-BatCoV HKU4, followed by the branch formed by Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013, but was only distantly related to NeoCoV. Thus, Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013 represent close relatives of MERS-CoV, while they occupied a position in between Ty-BatCoV HKU4 and Pi-BatCoV HKU5 in relation to MERS-CoV in S1 region.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analyses of RdRp, ORF1, S1 and N nucleotide sequences of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and other lineage C betacoronaviruses (B). The trees were constructed by maximum likelihood method using GTR+G substitution models respectively and bootstrap values calculated from 1000 trees. Trees were rooted using corresponding sequences of HCoV HKU1 (GenBank accession number NC_006577). Only bootstrap values >70% are shown. (A) 2775 nt (B) 20694 nt (C) 3740 nt (D) 1167 nt positions respectively were included in the analyses. The scale bars represent (A) 20 (B) 20 (C) 10 (D) 10 substitutions per site respectively. The two Hp-BatCoV HKU25 strains, YD131305 and NL140462, detected in this study are bolded and underlined.

Using the uncorrelated relaxed clock model on ORF1ab, tMRCA of human and camel MERS-CoVs was dated to 2009.56 (highest posterior density [HPD], 2006.8−2011.3), whereas that of MERS-CoV, NeoCoV, Hp-BatCoV HKU25, and BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013 was dated to 1939.32 (HPDs, 1899.5−1969.0) (Supplementary Figure 4).

Sequence Analysis of Hypsugo pulveratus Bat Coronavirus Spike Protein

The MERS-CoV uses hDPP4, a type II transmembrane protein, as receptor for initiation of infection [3]. The S1 domain responsible for hDPP4 receptor binding is located in a C-terminal 240-residue RBD that contains the receptor-binding motif, which engages the receptor [35]. Using binding and pseudovirus assays, it was shown that Ty-BatCoV HKU4 S, but not Pi-BatCoV HKU5 S, can bind to and use hDPP4 for cell entry [23, 36]. Because phylogenetic analysis placed Hp-BatCoV HKU25-S1 at a position between Ty-BatCoV HKU4 and Pi-BatCoV HKU5 in relation to MERS-CoV, it would be interesting to know whether Hp-BatCoV HKU25 may bind to and use hDPP4 for cell entry. As in other CoVs, Hp-BatCoV HKU25-S is predicted to be a type I membrane glycoprotein with 2 heptad repeats. The predicted Hp-BatCoV HKU25-S1-RBD shared 53.5% aa identities to that of MERS-CoV, with 2 short deletions compared with MERS-CoV and Ty-BatCoV HKU4 (Figure 3).

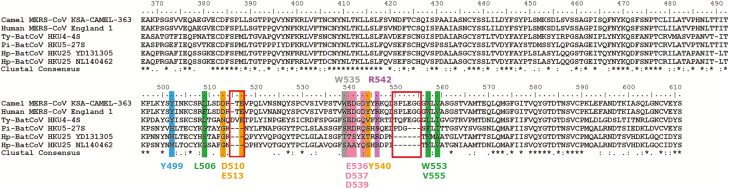

Figure 3.

Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequences of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein of MERS-CoV and corresponding sequences in Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and other lineage C betacoronaviruses. Asterisks indicate positions with fully conserved residues. The two amino acid deletions in Hp-BatCoV HKU25 compared to MERS-CoV and Ty-BatCoV HKU4 are indicated with boxes. The 12 critical residues for receptor binding in MERS-CoV are highlighted. The 10 residues marked below the alignment are based on (Wang, 2013) [37] and the other two residues marked above the alignment are based on (Wang, 2014) [23]. Y499 formed hydrogen bond with DPP4 residue. L506, W553 and V555 formed a hydrophobic core surrounded by hydrophilic residues D510, E513 and Y540. D510 and E513 also contributed to salt bridge interaction and hydrogen bonding with DPP4 residues. E536, D537 and D539 formed negative-charged surface. W535 and R542 are residues that have strong polar contact with DPP4 residues.

Previous structural studies have identified 12 critical residues (Y499, L506, D510, E513, W535, E536, D537, D539, Y540, R542, W553, and V555) for hDPP4 binding in MERS-CoV [23, 37]. In Ty-BatCoV HKU4, 5 (Y503, L510, E518, E541, and D542 corresponding to Y499, L506, E513, E536, and D537 in MERS-RBD) residues were conserved, which may allow binding to hDPP4. In Pi-BatCoV HKU5, 1 of the 12 conserved residues (D543 corresponding to D537 in MERS-RBD) was found. In Hp-BatCoV HKU25, 1 residue (R546 in strain YD131305/R547 in strain NL140462 corresponding to R542 in MERS-RBD) was conserved in both strains, and an additional residue (V554 corresponding to V555 in MERS-RBD) was conserved in strain NL140462 (Figure 3).

Hypsugo pulveratus Bat Coronavirus (CoV) HKU25-S1-Receptor-Binding Domain (S1-RBD) Binds Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 but With Lower Efficiency Than Middle East Respiratory Syndrome CoV S1-RBD

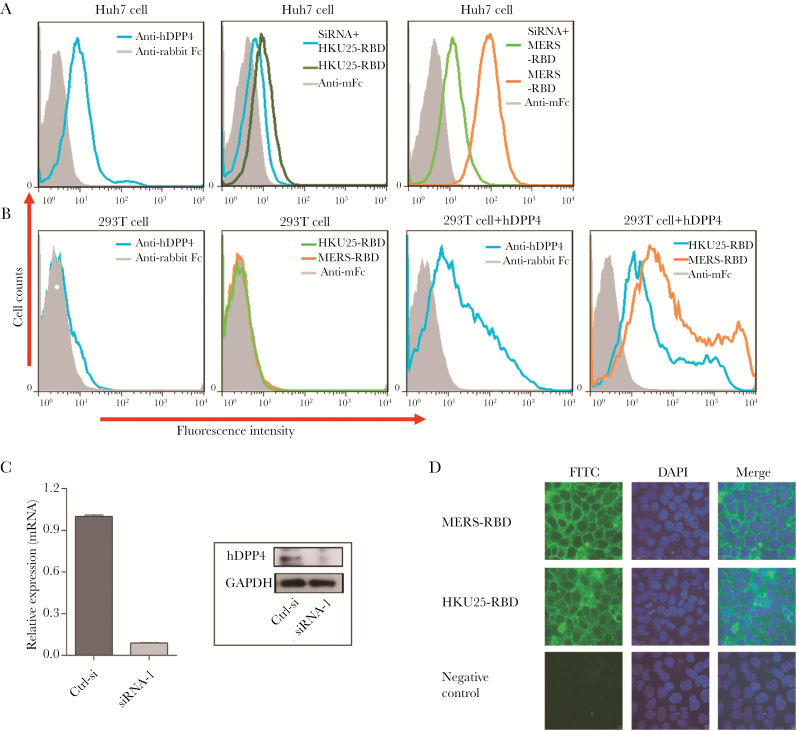

To examine the ability of Hp-BatCoV HKU25-S to bind hDPP4, we expressed and purified hDPP4 and the S1-RBD domains of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 (residues 374−604) and MERS-CoV (residues 367−606) using procedures described previously [32, 33]. We first tested the binding efficiency of the S1-RBD domains to Huh7 cells (human hepatocellular carcinoma cells with endogenous hDPP4 expression) using flow cytometry. The HKU25-RBD can bind to Huh7 cells, although the observed fluorescence shift was smaller than MERS-RBD (Figure 4A). This indicates that HKU25-RBD can bind to hDPP4-expressing Huh7 cells with lower binding efficiency than that of MERS-RBD. To confirm that the binding is mediated by hDPP4, we obtained Huh7 cells with siRNA knockdown of hDPP4 (confirmed by mRNA expression and Western blot) (Figure 4C). A significant reduction of fluorescence shift was observed in both HKU25-RBD- and MERS-RBD-mediated binding to hDPP4-knockdown Huh7 cells compared with hDPP4-expressing Huh7 cells (Figure 4A). Moreover, HKU25-RBD and MERS-RBD could only bind to HEK293T cells (lacking endogenous hDPP4 expression) after transfection with hDPP4-expressing plasmid, although the binding efficiency to hDPP4-expressing HEK293T cells was lower for HKU25-RBD than MERS-RBD (Figure 4B). Second, we also confirmed the binding of HKU25-RBD to Huh7 cell surface by confocal microscopy (Figure 4D). Third, immunoprecipitation assays showed that hDPP4 protein can be specifically pulled down by both MERS-RBD and HKU25-RBD (Figure 5). These results indicated that HKU25-RBD can bind to hDPP4 on cell surface but with lower efficiency than MERS-CoV-RBD.

Figure 4.

Binding of HKU25-RBD with human cells was mediated by interacting with human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) receptor. (A) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome receptor-binding domain (MERS-RBD)-mFc (10 µg/mL) and HKU25-RBD-mFc (40 µg/mL) binding to Huh7 cells and hDPP4-knockdown Huh7 cells. (B) FACS analysis of MERS-RBD-mFc and HKU25-RBD-mFc binding to 293T cells and 293T cells transfected with hDPP4-expressing plasmid. The shaded area represents the secondary antibody control. (C) Determination of small interfering ribonucleic acid (siRNA) efficiency by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot analysis using primers and antibody specific for hDPP4. (D) MERS-RBD-mFc and HKU25-RBD-mFc binding to a molecule(s) located on the Huh7 cell surface. MERS-RBD-mFc and HKU25-RBD-mFc were detected by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mFc antibody. Empty expressing plasmid was used as a negative control.

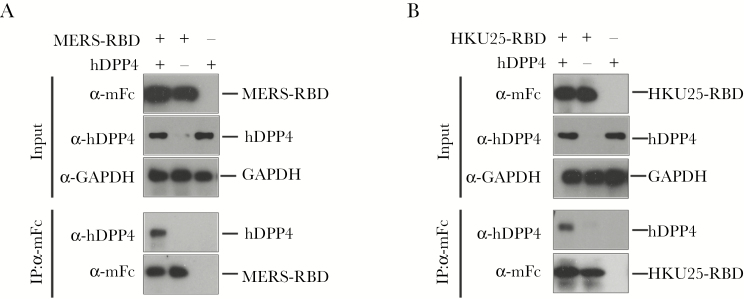

Figure 5.

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome receptor-binding domain (MERS-RBD)-mFc (A) and HKU25-RBD-mFc (B) proteins directly bind with human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4). HEK293 T cells were transfected with hDPP4-expressing plasmids, and MERS-RBD-mFc (A) and HKU25-RBD-mFc (B) proteins were used for immunoprecipitation of lysates of HEK293 T cells transfected with hDPP4-expressing or empty plasmids. Empty plasmid was mock-transfected as negative control. The hDPP4 was coprecipitated from the lysates, as detected by antibody specific for hDPP4. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control.

HKU25 Pseudovirus Can Use Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 for Cell Entry but With Lower Infection Efficiency Than Middle East Respiratory Syndrome and HKU4 Pseudoviruses

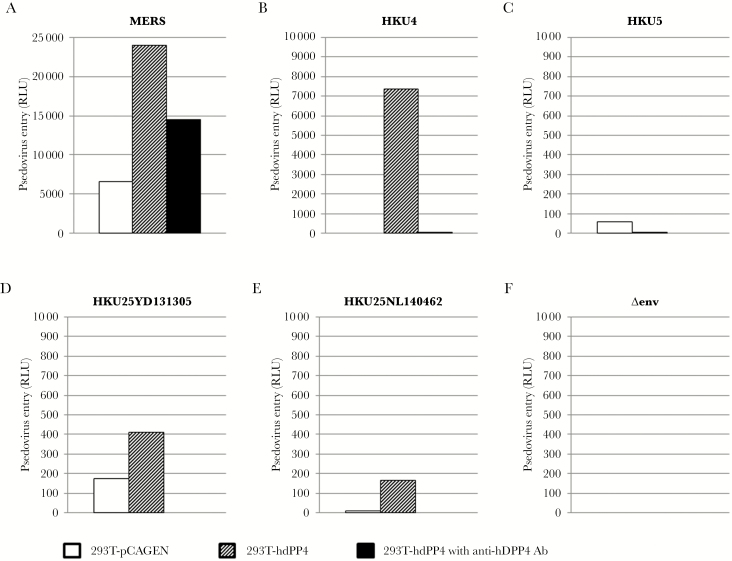

To determine whether Hp-BatCoV HKU25-S can mediate viral entry into hDPP4-expressing human cells, we performed HKU25-S-mediated pseudovirus entry assay. Because the S protein of Ty-BatCoV HKU4 but not that of Pi-BatCoV HKU5 can use hDPP4 for cell entry [36], we included HKU4-S-, HKU5-S-, and MERS-S-mediated pseudovirus entry assays for comparison. Pseudovirus assays were used because isolation of live Hp-BatCoV HKU25 was not successful, as with most bat CoVs that are often difficult to culture. Retroviruses pseudotyped with luciferase and the respective S proteins were tested for entry to HEK293T cells with or without hDPP4 expression. The MERS-S most robustly mediated pseudovirus entry into hDDP4-expressing HEK293T cells, followed by HKU4-S and HKU25-S, as shown by luciferase activities measured. All 3 pseudoviruses showed a marked increase in luciferase activities in hDDP4-expressing HEK293T cells compared with cells without hDPP4 expression (Figure 6). Moreover, anti-hDPP4 polyclonal antibodies could competitively block HKU25-S, HKU4-S, and MERS-S pseudovirus entry to hDPP4-expresssing HEK293T cells, further confirming the binding specificity. In contrast, HKU5-S and control retroviruses not pseudotyped with S did not mediate pseudovirus entry into hDPP4-expressing HEK293T cells (Figure 6). These results showed that hDPP4 is a possible functional receptor for Hp-BatCoV HKU25, although cell entry may be less efficient than Ty-BatCoV HKU4 and MERS-CoV.

Figure 6.

HEK293 T cells transfected with empty plasmid or human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (hDPP4) were infected by retroviruses pseudotyped with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), Ty-BatCoV HKU4, Pi-BatCoV HKU5, and Hp-BatCoV HKU25 S proteins with mock pseudovirus (∆env) as control. The cells were also preincubated with anti-hDPP4 antibodies (Ab) to test for cell entry inhibition. Cell entry efficiencies were assayed by luciferase activity measurement after 72 hours.

Structural Modeling of Receptor Binding Domain Human Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Binding Interphase

To predict the RBD-hDPP4 binding interface, the structures of HKU25-, MERS-, HKU4-, and HKU5-RBDs were modeled with that of hDPP4 using homology modeling. The sequence identity between HKU25-RBD and MERS-RBD (template) was >50%, and the RBD-hDPP4 interface for all RBDs was similar (Supplementary Figure 5), except that only MERS-RBD and HKU4-RBD possess the extended loop between β6 and β7 involved in interaction with hDPP4 [23]. A negative-charge residue, E536, located in MERS-RBD, corresponding to E541 in HKU4-RBD, can interact with the carbohydrate moiety of hDPP4, whereas HKU5-RBD contains a positive-charge residue, R542, and HKU25-RBD contains an uncharged residue, T540/A541, at the corresponding position. These findings supported that the binding of HKU25-RBD to hDPP4 may be weaker than that of MERS-RBD and HKU4-RBD but stronger than that of HKU5-RBD.

DISCUSSION

The novel lineage C betacoronavirus, Hp-BatCoV HKU25, helps to fill the evolutionary gap between existing bat viruses and MERS-CoV, and it offers new insights into the evolutionary origin of MERS-CoV. Hp-BatCoV HKU25 shared similar genome features with MERS-CoV, including the conserved ORF4a and ORF4b with predicted domains for double-stranded RNA binding and antagonizing interferon signals, respectively [38, 39]. Phylogenetically, Hp-BatCoV HKU25, together with BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013, was closely related to MERS-CoV and NeoCoV in most genome regions, suggesting that these viruses share a common ancestral origin. Although the S1 of NeoCoV is only distantly related to MERS-CoV, the S1 of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 was at a phylogenetic position closely related to MERS-CoV, only second to Ty-BatCoV HKU4. On the other hand, the S1 of NeoCoV is most closely related to Erinaceus CoV from European hedgehogs. Because NeoCoV was detected in an African bat, it is more likely a recombinant virus between bat and hedgehog CoVs in Africa. Moreover, it was shown that the S of BatCoV PREDICT/PDF-2180, which is closely related to NeoCoV in all genome regions, cannot mediate entry to hDPP4-expressing cells [13]. This further supported that NeoCoV and PREDICT/PDF-2180 are unlikely the immediate ancestors of MERS-CoV. On the other hand, Hp-BatCoV HKU25 and related viruses may represent close relatives to the immediate ancestor of MERS-CoV, based on its phylogenetic position in all genome regions including S protein.

The ability of Hp-BatCoV HKU25 to use hDPP4 for cell entry suggests that the S protein of related bat viruses may have evolved to cross the species barrier during the emergence of MERS-CoV. Using binding and pseudovirus assays, we demonstrated the ability of HKU25-S to bind to and use hDPP4 for cell entry,although with infection efficiency lower than that of MERS-S and HKU4-S. This is not only in line with the phylogenetic position of HKU25-S1 between HKU4-S1 (which can bind to hDPP4) and HKU5-S1 (which cannot), but it is also consistent with findings from structural modeling. Our results suggested that MERS-CoV may have originated from bat viruses having acquired a stepwise increasing ability to bind hDPP4 as they evolved. Previous molecular dating studies estimated that the time of divergence of MERS-CoVs was approximately 2010/2011 [40–43]. The present dating results are in line with such estimation, with the tMRCA of MERS-CoVs dated to approximately 2009, and that of MERS-CoV, NeoCoV, Hp-BatCoV HKU25, and BtVs-BetaCoV/SC2013 dated to approximately 1939. Therefore, the immediate ancestor of MERS-CoV could well have emerged from bats in the last century through evolution in its S protein before jumping to camels and humans.

The evolutionary path of MERS-CoV may be different from that of SARS-CoV. For SARS-CoV, the overlapping habitat and geographical distribution of different horseshoe bats in China is believed to have fostered viral recombination leading to the epidemic. The SARS-CoV is most likely a recombinant virus arising from ancestral viruses in horseshoe bats before it jumped to civet and then humans [44–47]. In contrast, there is currently no evidence to suggest that MERS-CoV is a recombinant virus. A previous study suggested that the genetically divergent S1 in NeoCoV may indicate intraspike recombination events involved in the emergence of MERS-CoV [11]. As explained above, NeoCoV, rather than MERS-CoV, is more likely a recombinant virus. On the other hand, a stepwise evolution of the S protein in gaining the ability to use camel and human DPP4 may be an important mechanism for interspecies transmission during the emergence of MERS-CoV.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results further support a possible bat origin of MERS-CoV and suggest that continuous surveillance of bats in the Middle East, Africa, and other regions may reveal the immediate animal origin of MERS-CoV. The application of similar state-of-the-art molecular studies on naturally evolving ancestral and intermediate viruses along the evolutionary path may provide further clues in understanding the mechanism of interspecies transmission of emerging viruses, while obviating the risks of generating dangerous mutants using the controversial, gain-of-function studies.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work is partly funded by Theme-Based Research Scheme (T11-707/15-R) and Research Grant Council Grant, University Grant Council; Health and Medical Research Fund (13121102) of the Food and Health Bureau of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR); Croucher Senior Medical Research Fellowships, Committee for Research and Conference Grant, Strategic Research Theme Fund, University Development Fund and Special Research Achievement Award, The University of Hong Kong; Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Disease for the HKSAR Department of Health; National Science and Technology Major Project of China (grant number 2012ZX10004213); and GDAS Special Project of Science and Technology Development (2017GDASCX-0107).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1. Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1814–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol 2013; 87:7790–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 2013; 495:251–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reusken CB, Haagmans BL, Müller MA et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:859–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28:465–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woo PC, Wang M, Lau SK et al. Comparative analysis of twelve genomes of three novel group 2c and group 2d coronaviruses reveals unique group and subgroup features. J Virol 2007; 81:1574–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Woo PC, Lau SK, Li KS et al. Molecular diversity of coronaviruses in bats. Virology 2006; 351:180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lau SK, Li KS, Tsang AK et al. Genetic characterization of Betacoronavirus lineage C viruses in bats reveals marked sequence divergence in the spike protein of pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 in Japanese pipistrelle: implications for the origin of the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol 2013; 87:8638–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woo PC, Lau SK, Li KS, Tsang AK, Yuen KY. Genetic relatedness of the novel human group C betacoronavirus to Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4 and Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5. Emerg Microbes Infect 2012; 1:e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corman VM, Ithete NL, Richards LR et al. Rooting the phylogenetic tree of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus by characterization of a conspecific virus from an African bat. J Virol 2014; 88:11297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang L, Wu Z, Ren X et al. MERS-related betacoronavirus in Vespertilio superans bats, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20:1260–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anthony SJ, Gilardi K, Menachery VD et al. Further evidence for bats as the evolutionary source of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. MBio 2017; 8:pii: e00373–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Hoek L, Pyrc K, Jebbink MF et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med 2004; 10:368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003; 361:1319–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woo PC, Lau SK, Chu CM et al. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol 2005; 79:884–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woo PC, Lau SK, Lam CS et al. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J Virol 2012; 86:3995–4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS et al. Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports the murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 and has implications for the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A. J Virol 2014; 89:3076–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai MM, Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res 1997; 48:1–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brian DA, Baric RS. Coronavirus genome structure and replication. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2005; 287:1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R et al. Coronaviridae. In: Virus Taxonomy, Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, International Union of Microbiological Societies, Virology Division; 2011: pp 806–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Boheemen S, de Graaf M, Lauber C et al. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. MBio 2012; 3:pii: e00473–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q, Qi J, Yuan Y et al. Bat origins of MERS-CoV supported by bat coronavirus HKU4 usage of human receptor CD26. Cell Host Microbe 2014; 16:328–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Agnarsson I, Zambrana-Torrelio CM, Flores-Saldana NP, May-Collado LJ. A time-calibrated species-level phylogeny of bats (Chiroptera, Mammalia). PLoS Curr 2011; 3:RRN1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Caì Y, Yú SQ, Postnikova EN et al. CD26/DPP4 cell-surface expression in bat cells correlates with bat cell susceptibility to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection and evolution of persistent infection. PLoS One 2014; 9:e112060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Munster VJ, Adney DR, van Doremalen N et al. Replication and shedding of MERS-CoV in Jamaican fruit bats (Artibeus jamaicensis). Sci Rep 2016; 6:21878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:14040–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yob JM, Field H, Rashdi AM et al. Nipah virus infection in bats (order Chiroptera) in peninsular Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7:439–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lau SK, Woo PC, Yip CC et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel betacoronavirus subgroup A coronavirus, rabbit coronavirus HKU14, from domestic rabbits. J Virol 2012; 86:5481–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang Y, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. CoVDB: a comprehensive database for comparative analysis of coronavirus genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36: D504–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lau SK, Wernery R, Wong EY et al. Polyphyletic origin of MERS coronaviruses and isolation of a novel clade A strain from dromedary camels in the United Arab Emirates. Emerg Microbes Infect 2016; 5:e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang X, Dong W, Milewska A et al. Human coronavirus HKU1 spike protein uses O-acetylated sialic acid as an attachment receptor determinant and employs hemagglutinin-esterase protein as a receptor-destroying enzyme. J Virol 2015; 89:7202–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun Y, Qi Y, Liu C et al. Nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA is a critical factor contributing to the efficiency of early infection of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. J Virol 2014; 88:237–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xiong L, Yang Y, Ye YN et al. Laribacter hongkongensis anaerobic adaptation mediated by arginine metabolism is controlled by the cooperation of FNR and ArgR. Environ Microbiol 2017; 19:1266–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lu G, Hu Y, Wang Q et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature 2013; 500:227–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang Y, Du L, Liu C et al. Receptor usage and cell entry of bat coronavirus HKU4 provide insight into bat-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:12516–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang N, Shi X, Jiang L et al. Structure of MERS-CoV spike receptor-binding domain complexed with human receptor DPP4. Cell Res 2013; 23:986–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Niemeyer D, Zillinger T, Muth D et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus accessory protein 4a is a type I interferon antagonist. J Virol 2013; 87:12489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thornbrough JM, Jha BK, Yount B et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus NS4b protein inhibits host RNase L activation. MBio 2016; 7:e00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cotten M, Watson SJ, Zumla AI et al. Spread, circulation, and evolution of the middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. MBio 2014; 5:pii: e01062–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sabir JS, Lam TT, Ahmed MM et al. Co-circulation of three camel coronavirus species and recombination of MERS-CoVs in Saudi Arabia. Science 2016; 351:81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cauchemez S, Fraser C, Van Kerkhove MD et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:50–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Drosten C, Seilmaier M, Corman VM et al. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:745–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lau SK, Li KS, Huang Y et al. Ecoepidemiology and complete genome comparison of different strains of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related rhinolophus bat coronavirus in china reveal bats as a reservoir for acute, self-limiting infection that allows recombination events. J Virol 2010; 84:2808–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hon CC, Lam TY, Shi ZL et al. Evidence of the recombinant origin of a bat severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like coronavirus and its implications on the direct ancestor of SARS coronavirus. J Virol 2008; 82:1819–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lau SK, Feng Y, Chen H et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus ORF8 protein is acquired from SARS-related coronavirus from greater horseshoe bats through recombination. J Virol 2015; 89:10532–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Song HD, Tu CC, Zhang GW et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:2430–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.