Abstract

It is extremely challenging to quantitate lumenal Ca2+ in acidic Ca2+ stores of the cell because all Ca2+ indicators are pH sensitive, and Ca2+ transport coupled to pH in acidic organelles. We have developed a fluorescent DNA-based reporter, CalipHluor, that is targetable to specific organelles. By ratiometrically reporting lumenal pH and Ca2+ simultaneously, it functions as a pH-correctable, Ca2+ reporter. By targeting CalipHluor to the endolysosomal pathway we mapped lumenal Ca2+ changes during endosomal maturation and found a surge in lumenal Ca2+ specifically in lysosomes. Using lysosomal proteomics and genetic analysis we found that catp-6, a C. elegans homolog of ATP13A2, was responsible for lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation - the first example of a lysosome-specific Ca2+ importer in animals. By enabling the facile quantification of compartmentalized Ca2+, CalipHluor can expand our understanding of subcellular Ca2+ importers.

Introduction

Ca2+ regulates diverse cellular functions upon its controlled release from different intracellular stores that initiates signaling cascadeszz1,2. Lysosomes have recently been recognized as “acidic Ca2+ stores”, and lumenal Ca2+ is central to its diverse functions3. Lysosome function is particularly important in neurons given the preponderance of lysosome-related genes in diverse neurological disorders including ~60 lysosomal storage disorders4. For example, risk genes for Parkinsons disease such as LRRK2, ATP6AP2, ATP13A2, and genetic risk associated GBA1 gene, are predicted to act in lysosomal pathways5.

Although electrophysiology has enabled the discovery of several channels that release lysosomal Ca2+, mediators of lysosomal Ca2+ import have not yet been identified3,6. Lysosomal Ca2+ release channels are amenable to investigation because Ca2+ release can be tracked using cytosolic Ca2+ dyes or genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators anchored to the cytoplasmic face of the lysosome7–9. Upon Ca2+ release, these probes indicate cytosolic Ca2+ in the area surrounding lysosomes. In contrast, lumenal Ca2+ cannot be quantitated, impeding the study of lysosomal Ca2+ importers. Consequently, lysosomal Ca2+ importers have not yet been identified in animals10, with the closest evidence being that the Xenopus CAX gene localizes in lysosomes upon overexpression11.

The inability to quantify Ca2+ in acidic organelles arises because all Ca2+ indicators function by coordinating Ca2+ through carboxylate groups that get protonated at acidic pH12. This changes probe affinity to Ca2+ ions. Further, organellar pH is coupled to lumenal Ca2+ entry and exit13. Thus, it is non-trivial to deconvolute the contribution of Ca2+ to the observed fluorescence changes of any Ca2+ indicator. Previous attempts used endocytic tracers bearing either pH or Ca2+ sensitive dyes to serially measure population-averaged pH and apparent Ca2+ in different batches of cells thus, scrambling information from individual endosomes 13–17. Given the broad pH distribution in endocytic organelles, this approach does not provide the resolution needed to study Ca2+ import18.

Here, we use a combination reporter for pH and Ca2+ to map both ions in parallel in the same endosome with single endosome addressability, achieving highly accurate measures of lumenal Ca2+. Using the pH reporter module of the combination reporter we deduce the pH in individual endosomes. By knowing exactly how the affinity of the Ca2+ sensitive module, i.e., its dissociation constant, Kd, changes with pH, we apply a Kd correction factor suited to the lumenal pH of each endosome to thereby compute the true value of lumenal Ca2+ with single-endosome resolution.

DNA nanodevices are versatile chemical reporters that can quantitatively map second messengers in real time, in living systems19–22. The modularity of DNA allows us to integrate distinct functions in precise stoichiometries into a single assembly. These include (i) a module to fluorescently sense a given ion (ii) a normalizing module for ratiometric quantitation and (iii) a targeting module to localize the reporter in a specific organelle19. We have thus measured H+ and Cl− in endocytic organelles20–24. Here we describe a DNA-based fluorescent reporter, CalipHluor, to quantitatively map organellar pH and Ca2+ simultaneously and with single organelle addressability. CalipHluor comprises four modules: a pH sensitive module; a Ca2+ sensitive fluorophore; an internal reference dye to ratiometrically quantitate pH as well as Ca2+ and finally, a targeting domain to transport CalipHluor to a specific organelle.

By targeting CalipHluor to the scavenger receptor-mediated endocytic pathway, we mapped lumenal Ca2+ as a function of endosomal maturation in nematodes. We found that Ca2+ is fairly low in early and late endosomes, followed by a ~35 fold surge in lumenal Ca2+ in lysosomes - implicating the existence of lysosome-specific Ca2+ import mechanisms. We identified the P5 Ca2+ATPase ATP13A2 as a potential candidate given its similarity to a well-known Ca2+ importer in the endoplasmic reticulum25. ATP13A2 transports divalent ions such as Mg2+, Mn2+, Cd2+, Zn2+ yet, has not been tested for its ability to transport Ca2+26,27. We showed that the C. elegans homolog of ATP13A2, catp-6, functions in opposition to the well-known lysosomal Ca2+ release channel, cup-5 28. We then showed that the human homolog, ATP13A2 also facilitates lysosomal Ca2+ entry by measuring lysosomal Ca2+ in fibroblasts derived from patients with Kufor Rakeb Syndrome. This constitutes the first example of a lysosomal Ca2+ importer in the animal kingdom.

Results and Discussion

Design and in vitro characterization of CalipHluor

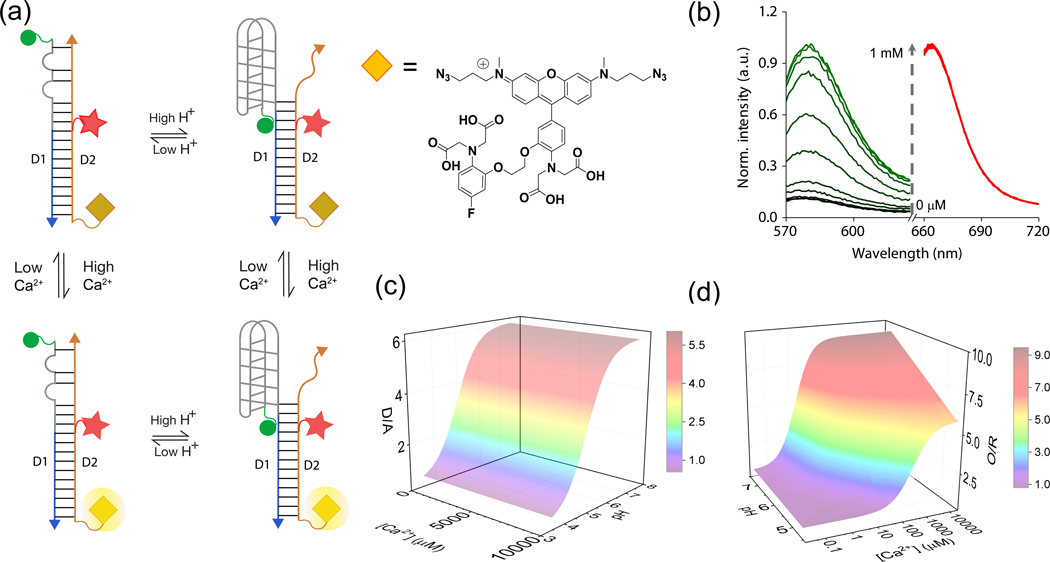

We describe the design and characterization of a fluorescent, DNA-based combination reporter for pH and Ca2+ called CalipHluorLy. CalipHluorLy is a 57-base pair DNA duplex comprising two strands D1 and D2 and bears three distinct domains (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table S1). The first domain in CalipHluorLy is a Ca2+-reporter domain that uses a novel small molecule that functions as a Ca2+ indicator that we denote Rhod-5F29. Rhod-5F consists of a BAPTA core, a rhodamine fluorophore (λex = 560 nm; λem = 580 nm) and an azide linker. In the absence of Ca2+, the rhodamine fluorophore in Rhod-5F is quenched by photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) from the BAPTA core. Upon Ca2+ chelation quenching is relieved resulting in high fluorescence. Note that protonation of the amines in BAPTA also relieves PeT12. Thus the percentage change in signal as well as the dissociation constant (Kd) in Rhod-5F will be affected as a function of pH. The Kd of Rhod-5F for Ca2+ binding is indeed pH dependent and shown in the supplementary information (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure-1: Design and characterization of CalipHluorLy.

(a) Working principle of CalipHluorLy. pH-induced FRET between Alexa488 (donor, D, green sphere) and Alexa647 (acceptor, A, red star) reports on pH ratiometrically. A Ca2+ sensitive dye (Rhod-5F, yellow diamond, λex=560 nm) and Alexa647 (λex=650 nm) report Ca2+ ratiometrically by direct excitation. (b) Fluorescence emission spectra of CalipHluorLy corresponding to Rhod-5F (green, O) and Alexa647 (red, R) with increasing [Ca2+] at pH = 7.2. (c) 3D-surface plot of donor to acceptor ratio (D/A) or pH response of CalipHluorLy as a function of pH and [Ca2+]. (d) 3D-surface plot of the Rhod-5F to Alexa647 ratio (O/R) or Ca2+ response of CalipHluorLy as a function of pH and [Ca2+].

Rhod-5F is attached to the D2 strand bearing a dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) group using click chemistry 30. Conjugation to D2 did not change the Kd of Rhod-5F in CalipHluorLy (Fig. 1b). In CalipHluorLy Rhod-5F (O, orange diamond) shows a Kd of 1.1 μM at pH 7.2 which increases as acidity increases (Fig. 1b).

For ratiometric quantification of Ca2+ we incorporate Alexa 647 as a reference dye (λex = 630 nm; λem = 665 nm) on CalipHluorLy positioned so that it does not FRET with Rhod-5F. Alexa 647 was chosen for its negligible spectral overlap with Rhod-5F and insensitivity to pH, Ca2+ and other ions (red circle, Fig. 1a). The fixed stoichiometry of Alexa 647 efficiently corrects for Rhod-5F intensity changes due to inhomogeneous probe distribution in cells, thus making the ratio of Rhod-5F (O) and Alexa 647 (R) intensities in CalipHluor probes proportional to pH and Ca2+. The second domain (gray line) constitutes a DNA based pH-reporter domain that we have previously described, called the I-switch20 (Fig. 1a). This I-switch has been used to map pH in diverse endocytic organelles in living cells20–24. To map pH in early and late endosomes we made CalipHluor, a variant suited to the lower acidities in these organelles (Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S2c). CalipHluor and CalipHluorLy were formed and characterized by gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Fig. S2 a–e). The third ‘integration’ domain comprises a 30-mer duplex, that integrates the pH and the Ca2+ reporter domains into a single DNA assembly. One end is fused to the I-switch and the other is fused to the Ca2+ sensor. This domain also helps in targeting, because its anionic nature aids recognition and trafficking by scavenger receptors in a DNA sequence independent manner 21.

The response characteristics of CalipHluor and CalipHluorLy were investigated as a function of pH as well as Ca2+ and their pH and Ca2+ sensitive regimes were determined (Fig. 1c–d and Supplementary Fig. S2f–g). A 3D surface plot of D/A as a function of pH and different values of free [Ca2+] is shown in Fig. 1c. These revealed that the pH reporting capabilities of CalipHluor and CalipHluorLy are between pH 5.0 – 7.0 and pH 4.0 – 6.5 with fold changes in D/A ratios of 4.0 and 5.5 respectively (Fig. 1c)21. Notably, the fold changes in D/A ratios were invariant over a range of free Ca2+ concentrations from 20 nM – 10 mM showing that pH sensing by these probes is unaffected by Ca2+ levels (Fig. 1c).

In parallel, the intensities of Rhod-5F (O) and Alexa647 (R) in CalipHluorLy obtained from direct excitation yielded O/R values. An analogous 3D surface plot of O/R values as a function of [Ca2+] and pH showed a sigmoidal increase as a function of Ca2+ with a ~9 fold change in O/R at pH 7.2 (Fig. 1d). At lysosomal pH in C. elegans, i.e., pH 5.5, CalipHluorLy showed a Kd of 7.2 μM. As expected, the percentage signal change upon chelating Ca2+ also decreases as acidity increases (Fig. 1d).

In vivo performance of CalipHluor.

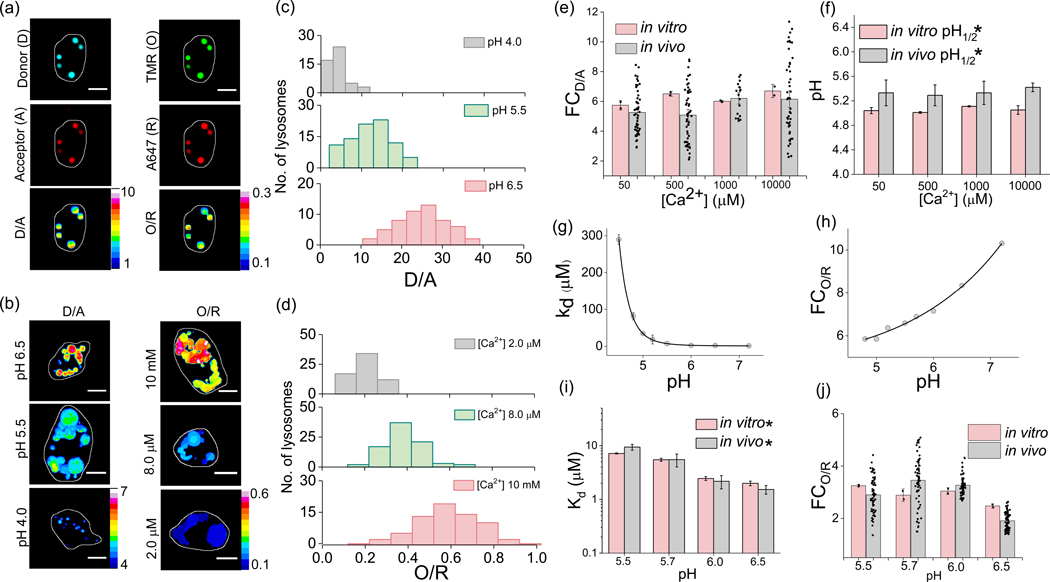

Next, we investigated the in vivo reporter characteristics of CalipHluorLy as a function of lumenal pH and [Ca2+]. When DNA-based reporters are injected into the pseudocoelom in C. elegans they are specifically uptaken by coelomocytes through the scavenger receptors mediated endocytosis and thereby label organelles on the endolysosomal pathway21,24. After labeling endocytic organelles with CalipHluorLy thus, we clamped lumenal pH and [Ca2+] of coelomocytes. This was achieved by incubating worms in clamping buffers of fixed pH and [Ca2+] containing nigericin, monensin, ionomycin and EGTA at high [K+] which clamped the endosomal ionic milieu to that of the surrounding buffer (Methods) 13,15,22,24. Post-clamping, the worms were then imaged in four channels; (i) the donor channel (D or Alexa 488) (ii) the FRET acceptor channel (A), which corresponds to the intensity image of A647 fluorescence upon exciting A488, (iii) the orange channel (O or Rhod-5F), and (iv) the red channel (R) which corresponds to the intensity image of A647 fluorescence upon directly exciting Alexa 647. Fig. 2a (i – iv) shows representative images of a CalipHluorLy labeled coelomocyte imaged in the four channels.

Figure-2: In vivo sensing characteristics of CalipHluorLy.

(a) Representative CalipHluorLy labelled coelomocytes imaged in the donor (D,i), acceptor (A,ii), Rhod-5F (O, iii) and Alexa647 (R, iv) channels. D/A (v) and O/R (vi) are the corresponding pixel-wise pseudocolor images. (b) Representative pseudo colored D/A and O/R maps of coelomocytes clamped at indicated pH and free [Ca2+] (c) Distribution of D/A ratios of ≥ 50 endosomes clamped at the indicated pH (n = 10 cells). (d) Distribution of O/R ratios of ≥ 50 endosomes clamped at different indicated free [Ca2+] (n = 10 cells). Comparison of (e) fold change of D/A ratios from pH 4 to 6.5 and; (f) pH1/2 from pH 4 to 6.5 of CalipHluorLy at different [Ca2+] obtained in vitro (peach) and in vivo (gray). CalipHluorLy (g) Dissociation constant Kd (μM) and (h) fold change of O/R as a function of pH. Comparison of (i) fold change in O/R ratio from 1 μM to 10 mM [Ca2+] and (j) Dissociation constant Kd (μM) of CalipHluorLy at the indicated pH obtained in vitro (peach) and in vivo (gray). Scale bars, 5 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. * Error is obtained from the non-exponential fit. Experiments were repeated thrice independently with similar results.

In a given clamping buffer of specified pH and Ca2+ concentration, the ratio of the donor channel (D) image to the acceptor channel (A) image yields a D/A image which corresponds to the clamping buffer pH (Fig. 2a (v)). Similarly, the O/R image corresponds to the Ca2+ concentration at that pH (Fig. 2a (vi)). Representative D/A and O/R images of coelomocytes clamped at the indicated pH and [Ca2+] are shown in Figure 2b (Methods)(Supplementary Fig. S3). The distribution of D/A and O/R values of lysosomes clamped at different indicated pH and [Ca2+] values are shown in Figures 2c–d. To compare the in vivo and in vitro sensing performances of both ion-sensing modules across a wide range of pH and Ca2+ we plotted two parameters for each module in CalipHluorLy. For the pH sensing module these were the fold change in D/A (FCD/A), as well as the transition pH (pH1/2) (Fig. 2e–f, Supplementary Fig. S4 a–d). For the Ca2+ sensing module, these were the fold change in O/R (FCO/R) as well as the Kd for Ca2+ (Fig. 2g - h). The values of FCD/A, FCO/R, pH1/2 and Kd in vivo and in vitro were consistent revealing that the in vitro performance characteristics of CalipHluorLy was quantitatively recapitulated in vivo (Fig. 2e–f and Fig 2i–k).

Measuring [Ca2+] in organelles of the endo-lysosomal pathway

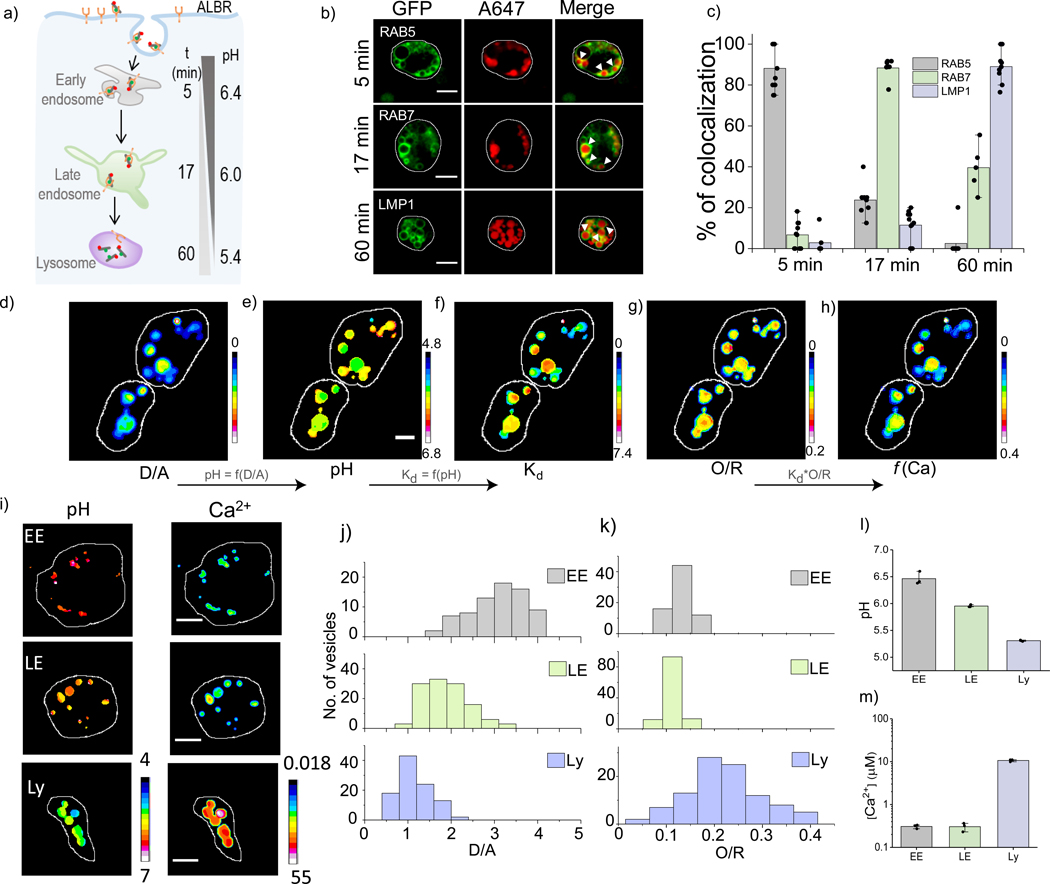

Endosomal maturation, critical to both organelle function and cargo trafficking, is accompanied by progressive acidification of the organelle lumen (Fig. 3a)31,32. Unlike pH, little is known about lumenal Ca2+ changes as a function of endosomal maturation16,17. We therefore sought to demonstrate the applicability of our probe across a range of acidic organelles by mapping lumenal Ca2+ as a function of endosomal maturation. We determined the time points at which CalipHluorLy localized in the early endosome, the late endosome and the lysosome in coelomocytes as described previously 21 (Fig. 3b–c). Post injection, CalipHluorLy was found to localize in early endosomes (EE), late endosomes (LE) and lysosomes (LY) at 5, 17 and 60 mins respectively (Fig. 3b–c, Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure-3: pH and [Ca2+] maps accompanying endosomal maturation.

(a) CalipHluor marks the indicated organelles in coelomocytes time dependently, by scavenger receptor mediated endocytosis. (b) Colocalization of CalipHluor and GFP-tagged markers of endocytic organelles at indicated time points post-injection in nematodes. (c) Quantification of colocalization in (b) (n = 10 cells, ≥ 50 endosomes) Pseudo color images of CalipHluorLy labelled lysosomes where the D/A map (d) is converted to the corresponding pH map (e), the pH map is converted into a Kd map (f) where the value of Kd is encoded pixelwise according to the pH at that pixel; the Kd map (f) is multiplied by the O/R map (g) to yield the Ca2+ map (h). (i) Representative pseudocolor pH and Ca2+ maps of early endosomes (EE), late endosomes (LE) and lysosomes (Ly) labelled with CalipHluor and CalipHluorLy. (j-l) Distributions of D/A and O/R ratios of EE, LE and Ly from n = 15 cells, 50 endosomes. (h) Mean endosomal pH of EE, LE and Ly. (i) Mean endosomal [Ca2+] in EE, LE and Ly data represent the mean ± s.e.m. Experiments were repeated thrice independently with similar results.

We measured pH and apparent Ca2+ at each stage in wild type N2 nematodes with single endosome addressability using our probes. We then incorporated a Kd correction factor for each endosome according to its measured pH, and then computed the true value of Ca2+ in every endosome. Figure 3d shows a representative set of coelomocytes for which this method of analysis was performed. We labeled early and late endosomes with CalipHluor whereas we labeled lysosomes with the CalipHluorLy variant and then generated the D/A and O/R maps of coelomocytes (Methods, Fig. 3d (i) & (iv)). The D/A map was directly converted into a pH map using the calibrated D/A values obtained from the in vivo pH clamping experiments (Fig. 3d(ii), Supplementary Table S2). The in vivo and in vitro Ca2+ response characteristics at every pH (Fig. 2h), provides the Kd for Ca2+ at every pH value for both CalipHluor and CalipHluorLy.

Using the pH map in Fig. 3d (ii) we constructed a “Kd map” which corresponds to the Kd for Ca2+ at each pixel in the pH map (Fig. 3d (iii), Supplementary Methods). Multiplying the value of Kd at each pixel in the Kd map with the equation (O/R - O/Rmin)/(O/Rmax-O/R) we obtain the true Ca2+ map (Fig. 3d(v)). In this equation, O/R corresponds to the observed O/R value at a given pixel in the O/R map, O/Rmin and O/Rmax correspond to O/R values at 1 μM and 10 mM Ca2+ at the corresponding pH value at that particular pixel. We thus obtained pH and Ca2+ maps of early endosomes, late endosomes and lysosomes in N2 worms (Fig. 3e) and the corresponding distributions of D/A and pH-corrected O/R are shown in Figures 3f–g. The mean values of pH and Ca2+ in each endosomal stage is shown in Figures 3h - i.

As expected, pH decreases progressively with endosomal maturation, with lumenal acidity showing a ~3-fold decrease at each endocytic stage. In contrast, Ca2+ in the early endosome and the late endosome were comparable and fairly low i.e., 0.3 μM. Interestingly, from the late endosome to the lysosome, lumenal Ca2+ increases sharply by ~35 fold, indicating a stage-specific enrichment of Ca2+ and consistent with the lysosome being an acidic Ca2+ store (Supplementary Table S3). The 100-fold difference between lysosomal and cytosolic Ca2+ is consistent with the stringent regulation of lysosomal Ca2+ channels to release lumenal Ca2+ and control lysosome function.

Catp-6 is identified as a potential lysosomal Ca2+ importer

This surge in lumenal Ca2+ specifically in the lysosome stage, implicates the existence of factors that aid lysosomal import of Ca2+. However, players that mediate lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation are still unknown in higher eukaryotes. We took inspiration from the well-known Ca2+ importer i.e., SERCA, a P-Type ATPase which is present on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)25. Other Ca2+ importers like plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) and the secretory pathway Ca2+ ATPase (SPCA1) are also P-type-ATPases33. Therefore we manually identified potential P-type ATPases in the human lysosomal proteome 34–38. We found the P5-ATPase ATP13A2 was described to transport cations like Mn2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, and Cd2+ but not Ca2+ based on toxicity assays26. As Ca2+ homeostasis is critical to all major signaling pathways, compensatory mechanisms in cells can counter excess Ca2+ and thereby omit the identification of Ca2+ transport by ATP13A2.

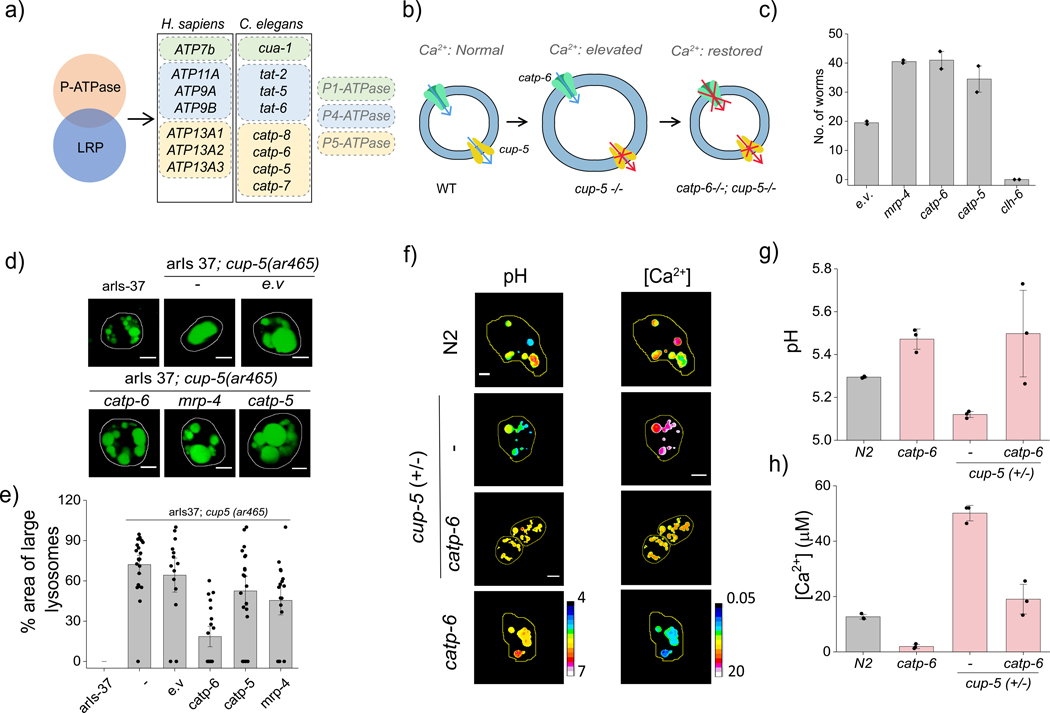

C. elegans has two homologs of ATP13A2 i.e., catp-5 and catp-6 (Fig. 4a). To test whether catp-6 mediated lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation, we investigated whether its knockdown would rescue a phenotype arising due to high lumenal Ca2+ (Fig. 4b). TRPML1 is a well-known lysosomal Ca2+ release channel whose knockdown would be expected to elevate lysosomal Ca2+39,40. Mutations in TRPML1 result in lysosomal dysfunction that leads to the lysosomal storage disease Mucopolysaccharidoses Type IV (MPS IV) 41. In C. elegans, loss of cup-5, the C. elegans homolog of TRPML1, results in lysosomal storage and embryonic lethality 42. We therefore tested whether catp-6 knockdown a cup-5+/− genetic background could reverse cup-5 −/− lethality. In this strain, the homozygous lethal deletion of cup-5 is balanced by dpy-10 marked translocation 43. We performed a survival assay by knocking down specific genes in cup-5+/− worms and scoring for lethality (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig S6).

Figure-4: Catp-6 facilitates lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation:

(a) P-type ATPases in human lysosomes obtained from the human Lysosome Gene Database (hLGDB). (b) Functional connectivity between catp-6 and cup-5. (c) Number of adult cup-5 +/− progeny where the indicated proteins are knocked down by RNAi. Data represents mean ± s.e.m. of three independent trials. (d) Representative fluorescence images of arIs37[myo-3p::ssGFP + dpy-20 (+)]I and arIs37; cup5(ar465) upon RNAi knockdown of the indicated proteins. (e) Percentage area occupied by enlarged lysosomes in the indicated genetic background. (n = 15 cells, ≥ 100 lysosomes). (f) pH and Ca2+ maps in CalipHluorLy-labeled lysosomes in coelomocytes in indicated genetic backgrounds (g) Mean lysosomal pH and (h) mean lysosomal [Ca2+] in the indicated genetic backgrounds. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. Scale bar 5 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Experiments were repeated thrice independently with similar results.

Multidrug resistance protein-4 (MRP-4) is a versatile efflux transporter for drugs, toxins, peptides and lipids and is known to rescue cup-5−/− lethality 44. It is hypothesized that in the absence of cup-5, mrp-4 mis-localizes in endocytic compartments causing toxicity that is then alleviated upon its knockdown. RNAi knockdown of either catp-6 or catp-5 rescued cup-5−/− lethality favorably compared to mrp-4 knockdown (Supplementary Fig S6). Knocking down clh-6, another lysosome-resident channel that regulates lumenal chloride, showed no such rescue24,28.

Catp-6 facilitates lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation

Given that the rescue of lethality might occur without restoring lysosomal function, we tested whether any of our candidate genes reversed lysosomal phenotypes. Cup-5 knockdowns show abnormally large lysosomes due to lysosomal storage 28. We therefore used the hypomorph ar645 with a G401E mutation in cup-5 leading to dysfunction that is insufficient for lethality, yet leads to engorged lysosomes45. In the arIs37;cup-5(ar465) strain, soluble GFP that is secreted from the muscle cells into the pseudocoelom is internalized by the coelomocytes and trafficked for degradation to dysfunctional lysosomes45. Thus, in these worms, the lysosomes in coelomocytes are abnormally enlarged and labeled with GFP (Fig. 4d).

RNAi knockdowns of catp-6 in these nematodes rescued lysosomal morphology (Fig. 4d–e, Methods). Knocking down either catp-5 or mrp-4 showed only a marginal recovery of phenotype. Given that mrp-4 is not a lysosome resident protein and its inability rescue the lysosomal phenotype suggests that mechanistically, its rescue of cup-5 −/− lethality is likely to be extra lysosomal, consistent with previous hypotheses.

We then checked whether catp-6-mediated rescue of a physical phenotype i.e., lysosome morphology, also led to a restoration of a chemical phenotype, i.e., its lumenal Ca2+. Lysosomal Ca2+ measurements using CalipHluorLy in cup-5 +/− nematodes and in catp-6 knockdowns we made. Wild type nematodes showed lysosomal Ca2+ levels of 11 ± 0.8 μM (Fig. 4f–h). In cup-5 +/− nematodes lysosomal Ca2+ was elevated to 40 ± 1.5 μM, consistent with cup-5 being a Ca2+ release channel (Fig. 4f–h). Interestingly, catp-6 knockdown restored lysosomal Ca2+ to wild-type levels. Thus catp-6 function directly opposes that of cup-5 as it rescues cup-5 deficient phenotypes at three levels - the whole organism in terms of lethality, at the sub-cellular level in terms of lysosome phenotype, at sub-organelle level in terms of its lumenal chemical composition. Cumulatively, these indicate that catp-6 facilitates lysosomal Ca2+ import. Accordingly, catp-6 deletion led to lysosomal Ca2+ dropping to 1.6 ± 0.4 μM, consistent with it facilitating Ca2+ import.

ATP13A2 facilitates lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation.

Mutations in ATP13A2, the human homolog of catp-6, belong to the PARK9 Parkinsons disease susceptibility locus. These mutations lead to the Kufor- Rakeb syndrome, a severe, early onset, autosomal recessive form of Parkinsons disease with dementia 46. Parkinsons disease is strongly connected to Ca2+ dysregulation since excessive cytosolic Ca2+ causes excitotoxicity of dopaminergic neurons 47. Interestingly, overexpressing ATP13A2 suppresses toxicity and reduces cytosolic Ca2+ 27,48. Further, loss of ATP13A2 function leads to neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, a lysosomal storage disorder, implicating the lysosome as its potential site of action 49.

To confirm whether i.e., ATP13A2, also facilitated lysosomal Ca2+ import, we mapped lysosomal Ca2+ in human fibroblasts. We created a variant called CalipHluormLy suited to measure the high acidity of mammalian lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. S7a). CalipHluormLy showed similar pH and Ca2+ response characteristics in vitro, on beads and in cellulo and its Ca2+ sensing characteristics are unaffected by the new pH sensing module (Supplementary Fig. S7b - e)

We then localized CalipHluormLy in lysosomes of primary human dermal fibroblasts (HDF cells) obtained from punch-skin biopsies. We showed that CalipHluormLy labels lysosomes in HDF cells by scavenger receptor mediated endocytosis (Fig. 5a–b Supplementary Fig. S8). Briefly, a 1 h pulse of 500 nM CalipHluormLy followed by a 9 h chase efficiently labels lysosomes in this cell type (Fig. 5a–b).

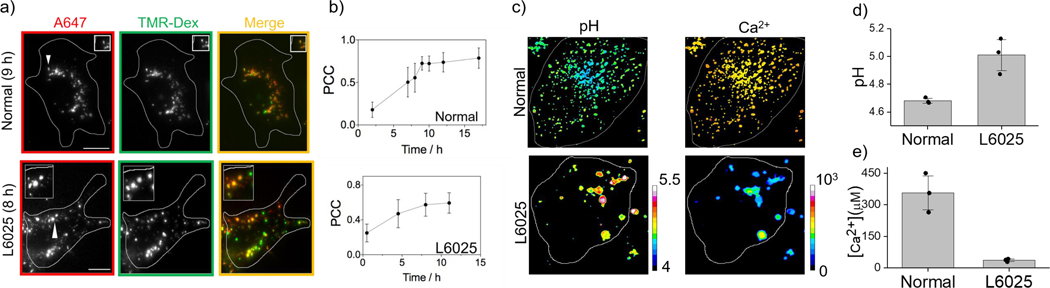

Figure-5: CalipHuormLy maps lysosomal Ca2+ in human cells:

a) Representative images of lysosomes in fibroblast cells from normal individuals and Kufor Rakeb syndrome patients (L6025S) labelled with TMR dextran (TMR; green) and CalipHluormLy (Alexa647, red). b) Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) of colocalization between CalipHluormLy and lysosomes as a function of time (n = 20 cells). c) Pseudocolor pH and Ca2+ maps of lysosomes in normal and L6025 fibroblasts (d) Mean lysosomal pH and (e) mean lysosomal [Ca2+] in normal and L6025 fibroblasts. (n = 5 cells; 50 endosomes) Scale bar: 10 μm. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. Experiments were repeated thrice independently with similar results.

We then measured lysosomal Ca2+ in fibroblasts from normal individuals and L6025 primary fibroblasts isolated from male patients with Kufor Rakeb syndrome, that are homozygous for a C>T mutation in 1550 of ATP13A2 50. This mutation results in ATP13A2 being unable to exit the ER and the lysosomes are devoid of ATP13A250. After confirming its lysosomal localization in L6025 cells, using CalipHluormLy we measured lysosomal pH and Ca2+ (Fig. 5b–d). Lysosomes in KRS patients showed 14-fold lower Ca2+ and ~2-fold lower [H+] than normal (Fig. 5c–e) confirming that ATP13A2 mediates lysosomal Ca2+ accumulation.

Conclusion

Small molecule as well as genetically encodable Ca2+ indicators have profoundly impacted biology. However, their pH sensitivity has restricted their use to the cytoplasm or the endoplasmic reticulum, where the pH is neutral and fairly constant. Ca2+ mapping of acidic microenvironments has therefore not been previously possible. Our DNA-based fluorescent reporter, CalipHluor, combines the photophysical advantages of small molecule Ca2+ indicators with the precise organelle targetability of endocytic tracers. CalipHluor is a pH-correctable Ca2+ reporter that simultaneously reports pH and Ca2+ in organelles retaining concentration information on both ions with single organelle addressability. Thus, by knowing exactly how the affinity (the Kd) of the Ca2+ sensitive probe changes with pH, we compute the Kd at every pixel in the pH map to generate a Kd map. From the Kd map and the O/R map, we can construct the true Ca2+ map of the acidic organelle.

Given the newfound ability to directly quantitate lysosomal Ca2+ using CalipHluor, we identified ATP13A2 - a risk gene for Parkinson’s disease - as a potential lysosomal Ca2+ importer. We found that the function of catp-6, the C. elegans homolog of ATP13A2, directly opposed that of a well-known lysosome-resident Ca2+ release channel, cup-5. It reversed cup-5 phenotypes at three different levels – a whole organism phenotype, a sub-cellular phenotype and an intra-lysosomal phenotype. This now provides a framework to identify more lysosomal Ca2+ regulators.

The ability to map pH and Ca2+ with single organelle addressability is critical to discriminate between lysosomal hypo-acidification and Ca2+ dysregulation. CalipHluor can be used to map lumenal Ca2+ changes in diverse organelles. There is already a range of DNA-based pH sensors specifically suited to organelles like the Golgi, the recycling endosome and the ER 19,20,22–24. Given the array of small molecule Ca2+ indicators covering various Ca2+ affinities, this positions CalipHluor technology to deliver new insights into organellar Ca2+ regulation.

Online Methods

Preparation of BAPTA-5F aldehyde (1)

BAPTA-5F aldehyde (1) was synthesized according to previous reported procedure 51,52. POCl3 (1.12g, 7.3 mmol) was added to DMF (5 mL) at 0 °C and allowed to stir for 10 min. After 10 min, BAPTA-5F (1.6 g, 2.9 mmol) in DMF (3mL) was added to above solution and heated to 65 °C. After completion of the reaction, reaction mixture was poured in water and pH adjusted to 6.0 by adding aq. NaOH (1M) solution. Product was extracted with ethylacetate (3×50 mL) and solvent was evaporated. Crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using hexane/EtOAc (70/30 to 60/40) as an eluent to obtain BAPTA-5F aldehyde (1) in 65% yield. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δppm 9.80 (s, 1H), 7.30–7.45 (m, 2H), 6.83 (t, 1H, J = 7 Hz), 6.76 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz), 6.59 (t, 2H, J = 8 Hz), 4.40 (t, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 4.35 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 4.33 (s, 4H), 4.22 (s, 4H), 3.59 (s, 6H), 3.57 (s, 6H). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δppm 190.5, 171.8, 171.2, 159.4, 157.5, 151.4, 151.3, 149.6, 145.1, 135.6, 135.5, 130.0, 126.9, 120.3, 120.2, 116.6, 110.8, 107.3, 107.1, 101.3, 101.1, 67.1, 67.0, 53.5, 53.4, 51.9, 51.7. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C27H31FN2O11+ 578.1912, found: 578.1927.

Synthesis of Rhod-5F

To a solution of BAPTA-5F aldehyde (1) (50 mg, 0.086 mmol) in propionic acid (4 mL), 3-(dimethylamino) phenol (26 mg, 0.19 mmol) and p-Toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA) (1.5 mg, 0.009 mmol) were added and allowed to stir at room temperature for 12 h. After 12 h, Chloranil (21 mg, 0.086 mmol) in DCM (3 mL) was added to above reaction mixture and allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. After completion of the reaction, the crude product was extracted with DCM (3×30 mL). The crude product was then purified by column chromatography on silica gel using DCM/Methanol (95/5 to 90/10 %) as an eluent to obtain methyl ester of Rhod-5F as a dark red solid in 35 % yield. LCMS (ESI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C43H48FN4O11+ 815.3298, found: 815.5. Methyl ester of Rhod-5F (5 mg, 0.006 mmol) was dissolved in methanol and water mixture (1:0.5 mL), to which KOH (3.5 mg, 0.063mmol) was added and allowed to stir for 8 h at room temperature. After completion of the reaction, solution pH was adjusted to 6.0 and crude product was extracted with DCM (3×5 mL). Product was purified by HPLC (50:50 acetonitrile/water, 0.1 % TFA) to obtained Rhod-5F. LCMS (ESI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C39H40FN4O11+ 759.2672, found: 759.4.

Preparation of 1-azido-3-iodopropane (2)

To a solution of 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (1 g, 6.4 mmol) in DMSO (8 mL), sodium azide (0.5 g, 7.7 mmol) was added and allowed to stir at room temperature for 12 h. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was diluted with water and the product was extracted with hexane to obtain 1-azido-3-chloropropane. Sodium iodide (1.5 g, 10 mmol) was then added to a solution of 1-azido3-chloropropane (1 g, 8.4 mmol) in acetone (25 mL) and allowed to stir at room temperature for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The crude product was diluted with a saturated solution of Na2S2O3 to quench the unreacted iodine followed by extraction of the compound with ethyl acetate (3×50 mL). This was dried over Na2SO4 and the product 1-azido-3-iodopropane (2) was used for further reactions without purification.

Preparation of 3-((3-azidopropyl)(methyl)amino)phenol (3)

To a solution of 3-aminophenol (1 g, 9.2 mmol) in acetone (30 mL), potassium carbonate (2.5 g, 18.4 mmol) was added and allowed to stir at room temperature for 20 min. After 20 min, iodomethane (1.3 g, 9.2 mmol) was added and the mixture was further stirred for 8 h at room temperature. After completion of reaction, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product was extracted with DCM (3×30 mL). This was followed by purification of the crude product by column chromatography on silica gel using hexane/ethyl acetate (80/20 %) as an eluent to obtained 3-(methylamino) phenol in 45 % yield.

To a solution of 3-(methylamino) phenol (1 g, 8.1 mmol) in DMF (8 mL), N, N-Diisopropylethylamine (1.26 g, 9.7 mmol) was added and stirred for 20 min at room temperature. After 20 min, 1-azido-3-iodopropane (2) (1.7 g, 8.1 mmol) was added to above reaction mixture and heated at 65 °C for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product was extracted with diethylether (3×40 mL). Then, the crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using hexane/ethyl acetate (90/10 %) as an eluent to obtained 3-((3-azidopropyl)(methyl)amino)phenol (3) liquid in 72 % yield. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δppm 7.09–7.13 (m, 1H), 6.3 (d, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.21 (dd, 2H, J = 2 Hz, 8.5 Hz), 3.42 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz), 3.38 (t, 2H, J = 7 Hz), 2.94 (s, 3H), 1.87 (t, 2H, J = 6.5 Hz). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δppm 156.7, 150.7, 130.2, 105.1, 103.5, 99.3, 49.8, 49.2, 38.6, 26.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C10H14N4O+ 206.1168, found:206.1177

Preparation of Rhod-5F-OMe (4)

To a solution of BAPTA-5F aldehyde (1) (50 mg, 0.086 mmol) in propionic acid (4 mL), 3-((3-azidopropyl)(methyl)amino)phenol (3) (40 mg, 0.19 mmol) and p-Toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA) (1.5 mg, 0.009 mmol) were added and allowed to stir at room temperature for 12 h. After 12 h, Chloranil (21 mg, 0.086 mmol) in DCM (3 mL) was added to above reaction mixture and allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. After completion of the reaction, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product was extracted with DCM (3×20 mL). The crude product was then purified by column chromatography on silica gel using DCM/Methanol (95/5 to 90/10 %) as an eluent to obtain Rhod-5F-OMe (4) as a dark red solid in 30 % yield. 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δppm 7.55 (d, 2H, J = 8 Hz), 7.15–7.16 (m, 3H), 7.00–7.04 (m, 3H), 6.88 (dd, 2H, J = 3 Hz, 9 Hz), 6.75 (dd, 1H, J = 6 Hz, 9 Hz), 6.65 (td, 1H, J = 3 Hz, 6 Hz), 4.20–4.30 (m, 8H), 4.02 (s, 4H), 3.71 (t, 4H, J = 7 Hz), 3.53 (s, 6H), 3.47 (s, 10H), 3.25 (s, 6H), 1.88 (q, 4H, J = 7 Hz). 13C-NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δppm 171.2, 171.1, 158.3, 157.3, 156.4, 156.1, 140.7, 135.2, 135.1, 131.9, 123.6, 123.1, 119.1, 116.8, 114.9, 114.4, 106.4, 106.2, 101.2, 101.0, 96.4, 67.3, 67.2, 54.9, 53.2, 53.0, 51.5, 51.2, 49.7, 48.6, 48.1, 26.0, 22.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C47H54FN10O11+ 953.3952, found: 953.3967.

Preparation of Rhod-5F-N3

Rhod-5F-OMe (4) (5 mg, 0.005 mmol) was dissolved in methanol and water mixture (1:0.5 mL), to which KOH (3.5 mg, 0.063mmol) was added and allowed to stir for 8 h at room temperature. After completion of the reaction, solution pH was adjusted to 6.0 and crude product was extracted with DCM (3×5 mL). Product was purified by HPLC (50:50 acetonitrile/water, 0.1 % TFA). LCMS (ESI) m/z: [M]+ calcd for C43H46FN10O11+ 897.3326, found: 897.5.

Reagents

All the chemicals used for the synthesis of Rhod-5F-N3 were purchased from Sigma (USA) and Alfa Aesar (USA). 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR were recorded on Bruker AVANCE II+, 500MHz NMR spectrophotometer in CDCl3 and DMSO-d6 and tetramethylsilane (TMS) used as an internal stranded. Mass spectra were recorded in Agilent 6224 Accurate-Mass TOF LC/MS.

All fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT (USA) and IBA-GmBh (Germany). HPLC purified oligonucleotides were dissolved in Milli-Q water to make 100 μM stock solutions and quantified using UV-spectrophotometer and stored at −20 °C. Ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N,N -tetraacetic acid (EGTA), ampicillin, carbencillin, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), nigericin and monensin were purchased from Sigma (USA) and ionomycin was obtained from Cayman chemical (USA). Maleylated BSA (mBSA) was maleylated according to a previously published protocol20. Monodisperse Silica Microspheres were obtained from Cospheric (USA).

Rhod-5F conjugation and sample preparation

Rhod-5F was first conjugated to D2 and O3-DBCO strands. Rhod-5F-N3 (25 μM) was added to 5 μM of dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) labelled D2 strand in 100 μL of sodium phosphate (10 mM) buffer containing KCl (100 mM) at pH 7.0 and allowed to stir overnight at room temperature. After completion of the reaction, 10 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5) and 250 μL of ethanol were added to reaction mixture and kept overnight at −20 °C for DNA precipitation 53. Then, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 14000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min to remove the unreacted Rhod-5F-N3 and the precipitate was resuspended in ethanol and centrifuged. This procedure was repeated 3 times for complete removal of unreacted Rhod-5F-N3. Rhod-5F conjugation was confirmed by gel electrophoresis by running a native polyacrylamide gel containing 15% (19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylaimde) in 1X TBE buffer [Tris.HCl (100 mM), boric acid (89 mM) and EDTA (2 mM), pH 8.3]. The same protocol was used for the conjugation of Rhod-5F-N3 to O3-DBCO.

To prepare a CalipHluorLy and CalipHluormLy sample, 5 μM of D1 or OG-D1 and 5 μM of Rhod-5F conjugated D2 strands were mixed in equimolar ratios in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 100 mM of KCl. The resultant solution was heated to 90 °C for 15 min, cooled to room temperature at 5 °C per 15 min and kept at 4 °C for overnight 20. For CalipHluor, 5 μM of O1-A488, 5 μM of O2-A647 and 5 μM of Rhod-5F conjugated O3 strands were mixed in equimolar ratios in 10mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 5.5 containing 100 mM of KCl. Solution was heated to 90 °C for 15 min, then cooled to room temperature at 3 °C per 15 min and kept at 4 C for overnight. See table S1 for sequence information.

In vitro fluorescence measurements

Fluorescence spectra were measured on a FluoroMax-4 spectrophotometer (Horiba Scientific, Edison, NJ, USA) using previously established protocols 20. For in vitro pH measurements, CalipHluorLy sample was diluted to 30 nM in pH clamping buffer [CaCl2 (50 μM to 10 mM), HEPES (10 mM), MES (10 mM), sodium acetate (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), KCl (140 mM), NaCl (5 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM)] of desired pH and equilibrated for 30 min at room temperature. All the samples were excited at 495 nm and emission spectra was collected from 505 nm to 750 nm. The ratio of donor (D) emission intensity at 520 nm to acceptor (A) emission intensity at 665 nm was plotted as a function of pH to generate the pH calibration curve. Mean of D/A from two independent experiments and their s.e.m were plotted for each pH. Fold change in D/A of CalipHluorLy was calculated from the ratios of D/A at pH 4.0 and pH 6.5. pH1/2 of CalipHluorLy at different [Ca2+] values were derived from pH calibration curve by fitting to Boltzmann sigmoid.

For in vitro [Ca2+] measurements, CalipHluorLy sample was diluted to 30 nM in Ca2+ clamping buffer [HEPES (10 mM), MES (10 mM), sodium acetate (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), KCl (140 mM), NaCl (5 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM)]. We then varied the amount of [Ca2+] from 0 mM to 20 mM and adjusted to different pH values (4.5–7.20). The amount of free [Ca2+] at a given pH was calculated based on Maxchelator software (http://maxchelator.stanford.edu/). Rhod-5F and Alexa 647 were excited at 545 nm and 630 nm respectively. Emission spectra for Rhod-5F (O) and Alexa 647 (R) were collected from 570–620 nm and 660–750 nm respectively. Mean of O/R from two independent experiments and their s.e.m were plotted for each [Ca2+]. Similar experiments were performed with 50nM CalipHluormLy at pH 4.6 and pH 5.1. In vitro calcium binding affinity (Kd) of Rhod-5F was obtained by plotting ratios of Rhod-5F (O) emission intensity at 580 nm to Alexa 647 (R) emission intensity at 665 nm as a function of free [Ca2+] and fitted using sigmoidal growth Hill1 equation.

| (1) |

X is free [Ca2+], Y is O/R ratio at given free [Ca2+], S is O/R ratio at low [Ca2+], E is O/R ratio at high [Ca2+], Kd is dissociation constant and n is Hill coefficient. Fold change response in O/R of CalipHluorLy was calculated from ratio of O/R at high [Ca2+] and O/R at low [Ca2+].

C.elegans methods and strains

Standard methods were followed for the maintenance of C. elegans 54. Wild type strain used was the C. elegans isolate from Bristol, strain N2 (Brenner, 1974). Strains used in the study, provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC), are RRID:WB-STRAIN:RB2510 W08D2.5(ok3473) and RRID:WBSTRAIN:VC1242 [+/mT1 II; cup-5(ok1698)/mT1 [dpy-10(e128)] III]. Transgenics used in this study, also provided by the CGC, are RRID:WB-STRAIN:NP1129 cdIs131 [pcc1::GFP::rab-5 + unc-119(+) + myo-2p::GFP], a transgenic strain that express GFP-fused early endosomal marker RAB-5 inside coelomocytes, RRID:WB-STRAIN:NP871 cdIs66 [pcc1::GFP::rab-7 + unc-119(+) + myo-2p::GFP], a transgenic strain that express GFP-fused late endosomal / lysosomal marker RAB-7 inside coelomocytes RRID:WB-STRAIN:RT258 pwIs50 [lmp-1::GFP + Cbr-unc-119(+)], a transgenic strain expressing GFP-tagged lysosomal marker LMP-1 and arIs37[myo-3p::ssGFP + dpy-20(+)]I, a transgenic strain that express ssGFP in the body muscles which secreted in pseudocoelom and endocytosed by coelomocytes and arIs37[myo-3p::ssGFP + dpy-20(+)]Icup5(ar465) a transgenic strain with enlarged GFP containing vesicles in coelomocytes due to defective degradation. Gene knocked down was performed using Ahringer library-based RNAi methods 55. The RNAi clones used were: L4440 empty vector control, catp-6 (W08D2.5, Ahringer Library), catp-5 (K07E3.7, Ahringer Library) and mrp-4 (F21G4.2, Ahringer Library).

CalipHluor trafficking in coelomocytes

CalipHluor trafficking in coelomocytes was done in transgenic strains expressing endosomal markers such as GFP::RAB-5 (EE), GFP::RAB-7 (LE) and LMP-1::GFP (Ly) as described previously by our lab 21. Briefly, worms were injected with CalipHluorA647 (500 nM) and incubated for specific time points and transferred on to ice. Worms were anaesthetized using 40 mM of sodium azide in M9 solution. Worms were then imaged on Leica TCS SP5 II STED laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL) using an Argon ion laser for 488 nm excitation and He-Ne laser for 633nm excitations with a set of filters suitable for GFP and Alexa 647 respectively. Colocalization of GFP and CalipHluorA647 was determined by counting the number CalipHluorA647 positive puncta that colocalize with GFP-positive puncta and quantified as a percentage of total number of CalipHluorA647 positive puncta21. In order to confirm lysosomal labeling in a given genetic background, the same procedure was performed on the relevant mutant or RNAi knockdown in pwIs50 [lmp-1::GFP + Cb-unc-119(+)].

RNAi experiments

Bacteria from the Ahringer RNAi library expressing dsRNA against the relevant gene was fed to worms, and measurements were carried out in one-day old adults of the F1 progeny (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003). RNA knockdown was confirmed by probing mRNA levels of the candidate gene, assayed by RT-PCR. Briefly, total RNA was isolated using the Trizol-chloroform method; 2.5 μg of total RNA was converted to cDNA using oligo-dT primers. 5 μL of the RT reaction was used to set up a PCR using gene-specific primers. Actin mRNA was used as a control. PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose-TAE gel.

Image acquisition

Image acquisition was carried out on wide field IX83 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA, USA) using a 60X, 1.42 NA, phase contrast oil immersion objective (PLAPON, Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA, USA) and Evolve Delta 512 EMCCD camera (Photometrics, USA). Filter wheel, shutter and CCD camera were controlled using Metamorph Premier Ver 7.8.12.0 (Molecular Devices, LLC, USA), suitable for the fluorophores used. Images on the same day were acquired under the same acquisition settings. Alexa 488 channel images (D) were obtained using 480/20 band pass excitation filter, 520/40 band pass emission filter and 89016-ET-FITC/Cy3/Cy5 dichroic filter. Alexa 647 channel images (A) were obtained using 640/30 band pass excitation filter, 705/72 band pass emission filter and 89016ET-FITC/Cy3/Cy5 dichroic filter. FRET channel images were obtained using the 480/20 band pass excitation filter, 705/72 band pass emission filter and 89016-ET-FITC/Cy3/Cy5 dichroic filter. Rhod-5F channel images (O) were obtained using 545/25 band pass excitation filter, 595/50 band pass emission filter and a 89016-ET-FITC/Cy3/Cy5 dichroic filter. Confocal images were acquired on a Leica TCS SP5 II STED laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) equipped with 63X, 1.4 NA, oil immersion objective. Alexa 488 was excited using an Argon ion laser for 488 nm excitation, Alexa 647 using He-Ne laser for 633 excitation and Rhod-5F using DPSS laser for 561 nm excitation with a set of dichroics, excitation, and emission filters suitable for each fluorophore.

Image analysis

Image analysis for quantification of pH and calcium in single endosomes was done using custom MATLAB code. For each cell the most focused plane was manually selected in the Alexa 647 channel. This image and corresponding images from the same z-position in other channels were input into the program. Images from the different channels were then aligned using Enhanced Cross Correlation Optimization 56. To determine the location of the endosome first a low threshold was used to select the entire cell. Only the area within the cell was subsequently considered for endosome selection. Regions of interest corresponding to individual endosomes were selected in the Alexa 647 channel by adaptive thresholding using Sauvolas method 57. The initial selection was further refined by watershed segmentation and size filtering. After segmentation regions of interest were inspected in each image and selection errors were corrected manually. Using the cell boundary annular region 10 pixels wide around the cell was selected and used to calculate a background intensity in each image. Then, we measured the mean fluorescence intensity in each endosome in donor (D), acceptor (A), Rhod-5F (O) and Alexa 647 (R) channels and the background intensity corresponding to that cell and channel was subtracted. The two ratios of intensities (D/A and O/R) were then computed for each endosome. Mean D/A of each distribution was plotted as a function of pH and obtained the in vivo pH calibration curve. Mean O/R of each distribution was plotted as a function of free [Ca2+] to generate the in vivo Ca2+ calibration curve. Pseudo color pH and Ca2+ images were obtained by measuring the D/A and O/R ratio per pixel, respectively.

In vivo measurements of pH and [Ca2+]

In vivo pH calibration experiments of CalipHluorLy were carried out using protocols previously established in our lab (Modi et al., 2009; Surana et al., 2011). Briefly, CalipHluorLy (500 nM) was microinjected in pseudocoelom of young adult worms on the opposite side of the vulva. After microinjections, worms were incubated at 22 °C for 2 h for maximum labelling of coelomocyte lysosomes. Then, worms were immersed in clamping buffer [CaCl2 (50 μM to 10 mM), HEPES (10 mM), MES (10 mM), sodium acetate (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), KCl (140 mM), NaCl (5 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM)] of desired pH solutions containing the ionophores nigericin (50 μM), monensin (50 μM) and ionomycin (20 μM). Worm cuticle was perforated to facilitate the entry of buffer in to the body. After 75 min of incubations in clamping buffer, coelomocytes were imaged using wide-field microscopy. Three independent measurements, each with 10 worms, were made for each pH value.

Ca2+ clamping measurements were carried out using CalipHluorLy. Worms were injected with CalipHluorLy (500 nM) and incubated at 22 °C for 2 h. After 2 h, worms were immersed in Ca2+ clamping buffer [HEPES (10 mM), MES (10 mM), sodium acetate (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), KCl (140 mM), NaCl (5 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM)] by varying amount of free [Ca2+] from 1 μM to 10 mM and adjusted to different pH values (5.3–6.5). Three independent measurements, each with 10 worms, were made for Ca2+ value.

Early endosome and late endosome pH and free [Ca2+] measurements were carried out using CalipHluor, and lysosomal pH and free [Ca2+] measurements were carried out using CalipHluorLy. For real time pH and [Ca2+] measurements, 10 hermaphrodites were injected with 500 nM of CalipHluor and CalipHluorLy for EE, LE and Ly respectively and incubated for the indicated time points (EE (5 min), LE (17 min) and Ly (60 min)). Worms were anaesthetized using 40 mM of sodium azide in M9 solution and imaged on wide field microscopy. Image analysis was carried out using custom MATLAB code as described in image analysis.

Calculating pH corrected [Ca2+] in EE, LE and Ly

The D/A and O/R ratios in Ly, LE and EE were measured using CalipHluorLy and CalipHluor as mentioned above at single endosome resolution. Over 100 endosomes were analyzed in each measurement in worms to generate a Gaussian spread of D/A. Around ~5%, endosomes which fell outside the range of Mean ± 2 S.D (S.D = standard deviation) which was set as a threshold for our measurements in EE, LE and Ly. To get pH corrected [Ca2+] values, we measured the pH value in each individual endosome with single endosome resolution from their D/A ratios. pH values in endosomes were calculated using equation (2) which was derived from our in vivo pH calibration curve,

| (2) |

K1, K2 and pH1/2 represent parameters derived from a Boltzmann fit of the in vivo pH calibration curve, and Y represents the D/A ratio in a given endosome.

Next, the Kd of CalipHluorLy and fold change response in O/R ratios of CalipHluorLy from low [Ca2+] O/R to high [Ca2+] were obtained as functions of pH. The in vitro and in vivo Kd were measured at different pH points ranging from 4.5 to 7.2 by fitting Ca2+ calibration curves by fitting to the Hill equation (1). From in vitro and in vivo [Ca2+] calibration curves, the Kd of CalipHluorLy was plotted as a function of pH using following equation,

| (3) |

By using equation, we can deduce Kd of CalipHluorLy at any given pH in EE, LE and Ly. O/Rmax (i.e., O/R ratio at high [Ca2+]), was obtained by clamping the worms at 10 mM of free [Ca2+] at different pH points. In vitro and in vivo [Ca2+] calibration curves showed that CalipHluorLy retained its fold-change response of O/R from 1 μM to 10 mM at different pH points. O/Rmin (i.e., O/R ratio at low [Ca2+]) values were calculated from fold change response as function of pH and normalized to O/Rmax.

| (4) |

As mentioned above, the pH in EE, LE and Ly was measured from D/A by using equation (2) at single endosome resolution. pH and O/R, were used to calculate Kd and O/Rmin from equation (3) and (4). Finally, Kd, O/Rmin, O/R and O/Rmax were substituted in the following equation to get pH corrected free [Ca2+] values in endosome by endosome level.

| (5) |

Three independent measurements, each with 10 worms, were made for pH and [Ca2+] values in EE, LE and Ly.

Image analysis – pH corrected [Ca2+] images

High resolution images were acquired using confocal microscopy as mentioned in methods section. Images were acquired in four channels (Alexa 488, FRET, Rhod-5F and Alexa 647 channels) to quantify pH and [Ca2+] at single endosome resolution. To compensate for the pH component in Ca2+ measurements, the Kd of CalipHluorLy at single endo-lysosomal compartments was calculated based on the Kd calibration plot discussed above. The pH of endo-lysosomes was quantified by measuring the donor/acceptor values calibrated across physiological pH (4.0–6.5). Donor (D) and acceptor (A) images were background subtracted by drawing an ROI outside the worms. Donor (D) image was duplicated and a threshold was set to create a binary mask. Background subtracted donor and acceptor images were then multiplied with the binary mask to get processed donor and acceptor images. This processed donor (D) image was divided by the processed acceptor (A) image to get a pseudo color D/A image, using Image calculator module of ImageJ 58. The pH value was calculated by using the equation (2) formulated from in vivo and in vitro pH calibration plot.

The pseudo colored pH image was processed to get a Kd image as shown in Fig. 3. Kd of CalipHluorLy is a function of pH and this relation is formulated by the Kd calibration plot in vivo and in vitro using equation (3). For image processing of pH image to Kd image, background was set to a non-zero value. The Kd image represents the affinity of CalipHluorLy for calcium and thus compensating the calcium image (O/R) with Kd would precisely represent the calcium levels at single endo-lysosomes. The pH dependent Kd compensation is performed according to equation (5), where O/Rmax and O/Rmin are calculated by incubating CalipHluor coated beads at 10mM and 1μM respectively. Image calculation were done using image calculator module in ImageJ. This image is multiplied with binary image to bring the background value to zero. The pH corrected Kd image were obtained for various mutants for accurate comparison of calcium levels in lysosomes.

Survival assay

+/mT1 II; cup-5(ok1698)/mT1 [dpy-10(e128)] III nematode strain was used for this assay43. Homozygous lethal deletion of cup-5 gene is balanced by dpy-10-marked translocation. Heterozygotes are superficially wildtype [cup5+/−], Dpys (mT1 homozygotes) are sterile, and cup5(ok1698) homozygotes are lethal. cup5+/− L4 worms were placed on plates containing RNAi bacterial strains for L4440 empty vector (positive control), mrp-4, catp-6, catp-5 and clh-6. These worms were allowed to grow for 24 h and lay eggs after which the adult worms were removed from the plates. The eggs were allowed to hatch and grow to adult for 3 days. The worm plates were then imaged under Olympus SZX-Zb12 Research Stereomicroscope (Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA, USA) with a Zeiss Axiocam color CCD camera (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY, USA). The images were analyzed using ImageJ software to count the number of adult worms per plate. Three independent plates were used for each RNAi background.

Lysosomal size recovery assay

arIs37 [myo-3p::ssGFP + dpy-20(+)] I. cup-5(ar465) is transgenic nematode strain which secretes GFP from the body muscle cells and this is endocytosed by coelomocytes which show enlarged GFP labelled vesicles as a result of defective degradation caused by cup 5 mutation 28. Similar to the previous assay, arIs37; cup-5(ar465) L4 worms were placed on plates containing RNAi bacterial strains for empty vector (control), catp-6, catp-5 and mrp-4 (positive control). The worms lay eggs for 24 hours after which they are removed from the plates. The eggs thus hatch and grow to adulthood after which they were imaged to check for lysosomal size differences. Worms were imaged on a Leica TCS SP5 II STED laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) equipped with 63X, 1.4 NA, oil immersion objective upon excitation with Argon laser in the Alexa 488 channel. Lysosomal areas were measured using ImageJ. Out 100 lysosomes in arIs37 worms, 7 lysosomes had an area in range of 7.0–9.5 μm2. Enlarged lysosomes are defined as those lysosomes whose diameter is ≥ 33% of the diameter of the largest lysosome observed in normal N2 worms. We measured the lysosomal area in arIs37; cup-5(ar465) worms in various RNAi bacteria containing plates. Lysosomal size recovery data was plotted as percentage of area occupied by large lysosomes to the total lysosomal area (n = 15 cells, > 100 lysosomes).

Bead calibration of CalipHluormLy

Bead calibration was performed using CalipHluormLy coated 0.6μm Monodisperse Silica Microspheres (Cospheric, USA). Briefly, silica microspheres were incubated in a solution of 5μM CalipHluormLy in 20mM Sodium Acetate buffer (pH= 5.1) and 500mM NaCl for 1 h59,60. This binding solution was then spun down and the beads were reconstituted in clamping buffer [HEPES (10 mM), MES (10 mM), sodium acetate (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), KCl (140 mM), NaCl (500 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM)]. We then varied the amount of [Ca2+] from ~0mM to 10 mM and adjusted the pH to either pH 4.6 or pH 5.1. The beads were incubated in clamping buffer for 30 mins after which there were imaged on a slide on the IX83 inverted microscope in the G, O and R channels to obtain G/R (pH) and O/R (Ca2+) images.

Cell culture methods and maintenance

Human dermal fibroblasts (HDF) were a kind gift from Late Professor Janet Rowley’s Lab at the University of Chicago and human fibroblast cells harboring mutations in ATP13A2 (L6025) were a kind gift from Krainc Lab, Northwestern University, Chicago. L6025 is homozygous for 1550C>T. Control and mutant fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Invitrogen Corporation, USA) containing 10% heat inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Invitrogen Corporation, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin and maintained at 37°C under 5 % CO2.

Competition experiments in cells

HDF cells were washed with 1× PBS buffer pH 7.4 prior to labeling. Cells were incubated with 10 μM of maleylated BSA (mBSA) or BSA for 15 min and pulsed with media containing 500 nM CalipHluormLy and 10 μM of mBSA or BSA for 1 h to allow internalization by receptor mediated endocytosis, washed 3 times with 1× PBS and then imaged under a wide-field microscope. Whole cell intensities in the Alexa 647 channel was quantified for >30 cells per dish. The mean intensity from three different experiments were normalized with respect to the autofluorescence and presented as the fraction internalized.

Colocalization in cells

We used lysosomes pre-labeled with 10kDa TMR-Dextran (TMR-Dex) to study the trafficking time scales for our probes. TMR Dex was pulsed for 1 h, chased for 16 h in fibroblast cells followed by imaging. Pre-labeled cells were pulsed with 500nM of CalipHluorA647Ly and chased for indicated time and imaged. Cross talk and bleed-through were measured and found to be negligible between the TMR channel and Alexa 647 channel. Pearsons correlation coefficient (PCC) measures the pixel-by-pixel covariance in the signal levels of two images. Tools for quantifying PCC are provided in Fuji software. Pearsons correlation coefficient (PCC) measures the pixel-by-pixel covariance in the signal levels of two images. Tools for quantifying PCC are provided in Fuji software.

In cellulo measurements pH and calcium measurements

pH and calcium clamping were carried out using CalipHluormLy. Fibroblast cells were pulsed for 1 h and chased for 2 h with 500nM CalipHluormLy. Cells are then fixed with 200 mL 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min at room temperature, washed three times and retained in 1× PBS. To obtain the intracellular pH and calcium calibration profile, endosomal calcium concentrations were equalized by incubating the previously fixed cells in the appropriate calcium clamping buffer [HEPES (10 mM), MES (10 mM), sodium acetate (10 mM), EGTA (10 mM), KCl (140 mM), NaCl (5 mM) and MgCl2 (1 mM)] by varying amount of free [Ca2+] from 1 μM to 10 mM and adjusted to different pH values. The buffer also contained nigericin (50 μM), monensin (50 μM) and ionomycin (20 μM) and the cells were incubated for 2 h at room temperature.

For realtime pH and calcium measurements, fibroblast cells are pulsed with 500nM of CalipHluormLy for 1 h, chased for 9 h (8 h for L0625 cells) and then washed with 1× PBS and imaged in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). Imaging was carried out on IX83 research inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA, USA) using a 100X, 1.42 NA, DIC oil immersion objective (PLAPON, Olympus Corporation of the Americas, Center Valley, PA, USA) and Evolve Delta 512 EMCCD camera (Photometrics, USA).

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Life Sciences Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor John Kuriyan and Matthew Zajac for valuable comments. We thank the Integrated Light Microscopy facility at the University of Chicago, the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (CGC) for strains and Ausubel Lab for Arhinger Library RNAi clones. This work was supported by the University of Chicago Women’s Board, Pilot and Feasibility award from an NIDDK center grant P30DK42086 to the University of Chicago Digestive Diseases Research Core Center, MRSEC grant no. DMR-1420709, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through Grant Number 1UL1TR002389-01 that funds the Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM), Chicago Biomedical Consortium with support from the Searle Funds at The Chicago Community Trust, C-084 and University of Chicago start-up funds to Y.K. Y.K. is a Brain Research Foundation Fellow.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Clapham DE Calcium signaling. Cell 131, 1047–1058 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagur R. & Hajnóczky G. Intracellular ca2+ sensing: its role in calcium homeostasis and signaling. Mol. Cell 66, 780–788 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang J, Zhao Z, Gu M, Feng X. & Xu H. Release and uptake mechanisms of vesicular Ca2+ stores. Protein Cell (2018). doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0523-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parenti G, Andria G. & Ballabio A. Lysosomal storage diseases: from pathophysiology to therapy. Annu. Rev. Med 66, 471–486 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plotegher N. & Duchen MR Crosstalk between Lysosomes and Mitochondria in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 5, 110 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Martinoia E. & Szabo I. Organellar channels and transporters. Cell Calcium 58, 1–10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calcraft PJ et al. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature 459, 596–600 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang P. et al. P2X4 forms functional ATP-activated cation channels on lysosomal membranes regulated by luminal pH. J. Biol. Chem 289, 17658–17667 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiselyov K. et al. TRPML: transporters of metals in lysosomes essential for cell survival? Cell Calcium 50, 288–294 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lloyd-Evans E. On the move, lysosomal CAX drives Ca2+ transport and motility. J. Cell Biol 212, 755–757 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melchionda M, Pittman JK, Mayor R. & Patel S. Ca2+/H+ exchange by acidic organelles regulates cell migration in vivo. J. Cell Biol 212, 803–813 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan AJ, Davis LC & Galione A. Imaging approaches to measuring lysosomal calcium. Methods Cell Biol. 126, 159–195 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen KA, Myers JT & Swanson JA pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages. J. Cell Sci 115, 599–607 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd-Evans E. et al. Niemann-Pick disease type C1 is a sphingosine storage disease that causes deregulation of lysosomal calcium. Nat. Med 14, 1247–1255 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrity AG et al. The endoplasmic reticulum, not the pH gradient, drives calcium refilling of lysosomes. Elife 5, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherwood MW et al. Activation of trypsinogen in large endocytic vacuoles of pancreatic acinar cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5674–5679 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerasimenko JV, Tepikin AV, Petersen OH & Gerasimenko OV Calcium uptake via endocytosis with rapid release from acidifying endosomes. Curr. Biol 8, 1335–1338 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson DE, Ostrowski P, Jaumouillé V. & Grinstein S. The position of lysosomes within the cell determines their luminal pH. J. Cell Biol 212, 677–692 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborty K, Veetil AT, Jaffrey SR & Krishnan Y. Nucleic Acid-Based Nanodevices in Biological Imaging. Annu. Rev. Biochem 85, 349–373 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Modi S. et al. A DNA nanomachine that maps spatial and temporal pH changes inside living cells. Nat. Nanotechnol 4, 325–330 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surana S, Bhat JM, Koushika SP & Krishnan Y. An autonomous DNA nanomachine maps spatiotemporal pH changes in a multicellular living organism. Nat. Commun 2, 340 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saha S, Prakash V, Halder S, Chakraborty K. & Krishnan Y. A pH-independent DNA nanodevice for quantifying chloride transport in organelles of living cells. Nat. Nanotechnol 10, 645–651 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modi S, Nizak C, Surana S, Halder S. & Krishnan Y. Two DNA nanomachines map pH changes along intersecting endocytic pathways inside the same cell. Nat. Nanotechnol 8, 459–467 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakraborty K, Leung K. & Krishnan Y. High lumenal chloride in the lysosome is critical for lysosome function. Elife 6, e28862 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toyoshima C. & Inesi G. Structural basis of ion pumping by Ca2+-ATPase of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem 73, 269–292 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt K, Wolfe DM, Stiller B. & Pearce DA Cd2+, Mn2+, Ni2+ and Se2+ toxicity to Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacking YPK9p the orthologue of human ATP13A2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 383, 198–202 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramonet D. et al. PARK9-associated ATP13A2 localizes to intracellular acidic vesicles and regulates cation homeostasis and neuronal integrity. Hum. Mol. Genet 21, 1725–1743 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fares H. & Greenwald I. Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homolog. Nat. Genet 28, 64–68 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salgado EN, Garcia Rodriguez B, Narayanaswamy N, Krishnan Y. & Harrison SC Visualization of Ca2+ loss from rotavirus during cell entry. J. Virol (2018). doi: 10.1128/JVI.01327-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jewett JC, Sletten EM & Bertozzi CR Rapid Cu-free click chemistry with readily synthesized biarylazacyclooctynones. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 3688–3690 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huotari J. & Helenius A. Endosome maturation. EMBO J. 30, 3481–3500 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Y-B, Dammer EB, Ren R-J & Wang G. The endosomal-lysosomal system: from acidification and cargo sorting to neurodegeneration. Transl Neurodegener 4, 18 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandecaetsbeek I, Vangheluwe P, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F. & Vanoevelen J. The Ca2+ pumps of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 3, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tharkeshwar AK et al. A novel approach to analyze lysosomal dysfunctions through subcellular proteomics and lipidomics: the case of NPC1 deficiency. Sci. Rep 7, 41408 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapel A. et al. An extended proteome map of the lysosomal membrane reveals novel potential transporters. Mol. Cell Proteomics 12, 1572–1588 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lübke T, Lobel P. & Sleat DE Proteomics of the lysosome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 625–635 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brozzi A, Urbanelli L, Germain PL, Magini A. & Emiliani C. hLGDB: a database of human lysosomal genes and their regulation. Database (Oxford) 2013, bat024 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schröder BA, Wrocklage C, Hasilik A. & Saftig P. The proteome of lysosomes. Proteomics 10, 4053–4076 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao Q, Yang Y, Zhong XZ & Dong X-P The lysosomal Ca2+ release channel TRPML1 regulates lysosome size by activating calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem 292, 8424–8435 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sahoo N. et al. Gastric Acid Secretion from Parietal Cells Is Mediated by a Ca2+ Efflux Channel in the Tubulovesicle. Dev. Cell 41, 262–273.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bargal R. et al. Identification of the gene causing mucolipidosis type IV. Nat. Genet 26, 118–123 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaheen L, Dang H. & Fares H. Basis of lethality in C. elegans lacking CUP-5, the Mucolipidosis Type IV orthologue. Dev. Biol 293, 382–391 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.elegans C. Deletion Mutant Consortium. large-scale screening for targeted knockouts in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. G3 (Bethesda) 2, 1415–1425 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaheen L, Patton G. & Fares H. Suppression of the cup-5 mucolipidosis type IV-related lysosomal dysfunction by the inactivation of an ABC transporter in C. elegans. Development 133, 3939–3948 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fares H. & Greenwald I. Genetic analysis of endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans: coelomocyte uptake defective mutants. Genetics 159, 133–145 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Veen S. et al. Cellular function and pathological role of ATP13A2 and related P-type transport ATPases in Parkinson’s disease and other neurological disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci 7, 48 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schöndorf DC et al. iPSC-derived neurons from GBA1-associated Parkinson’s disease patients show autophagic defects and impaired calcium homeostasis. Nat. Commun 5, 4028 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Usenovic M, Tresse E, Mazzulli JR, Taylor JP & Krainc D. Deficiency of ATP13A2 leads to lysosomal dysfunction, α-synuclein accumulation, and neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci 32, 4240–4246 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bras J, Verloes A, Schneider SA, Mole SE & Guerreiro RJ Mutation of the parkinsonism gene ATP13A2 causes neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. Hum. Mol. Genet 21, 2646–2650 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Estrada-Cuzcano A. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the ATP13A2/PARK9 gene cause complicated hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG78). Brain 140, 287–305 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 51.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M. & Tsien RY A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem 260, 3440–3450 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collot M. et al. CaRuby-Nano: a novel high affinity calcium probe for dual color imaging. Elife 4, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore D. & Dowhan D. Purification and concentration of DNA from aqueous solutions. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol Chapter 2, Unit 2.1A (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kamath RS & Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30, 313–321 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evangelidis GD & Psarakis EZ Parametric image alignment using enhanced correlation coefficient maximization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell 30, 1858–1865 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sauvola J. & Pietikäinen M. Adaptive document image binarization. Pattern Recognit 33, 225–236 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schindelin J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engelstein M. et al. An efficient, automatable template preparation for high throughput sequencing. Microb. Comp. Genomics 3, 237–241 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vandeventer PE et al. Multiphasic DNA adsorption to silica surfaces under varying buffer, pH, and ionic strength conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 5661–5670 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper and the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.