Abstract

We report the first case of transmission of Panton-Valentine leukocidin–producing Staphylococcus aureus to a physician during the resuscitation of an infant with fatal pneumonia. The physician exhibited numerous furuncles. This case highlights the necessity for health care workers to protect themselves against transmission of infectious diseases from patient to care giver.

Severe respiratory diseases, in immunocompetent infants, and chronic furunculosis have been associated with Staphylococcus aureus strains producing Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), a cytotoxin that causes leukocyte destruction and tissue necrosis [1]. PVL-producing S. aureus is known to cause rapidly extensive and necrotizing pneumonia in children and young adults. We report the first case, to our knowledge, of transmission of PVL-producing S. aureus to a physician during the resuscitation of an infant with fatal pneumonia.

Case report. A 4-month-old boy was admitted to the pediatric ward of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul hospital (Paris) with a history of 3 days of cough and 1 day of moderate fever. Physical examination revealed only mild respiratory distress. Findings on a chest radiogram were normal, as were the WBC count and the C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels. Bronchiolitis was diagnosed, and the patient did not receive antibiotics. Progressive respiratory failure developed during the 12 h after admission, and the patient required nasal oxygenation. While a physical examination was being performed by a physician, the patient experienced cardiac arrest. Resuscitation measures, including oral intubation, oxygenation, bag-valve-mask ventilation, chest compression, and intravenous administration of adrenaline, were immediately performed and were continued for 1 h, without success. It was notable that blood flow from the trachea was observed during intubation. Repeated oral and tracheal suction was performed. Because the resuscitation took place in the general pediatric ward, health care workers participating in the resuscitation did not wear any protection, such as a facial mask and gloves. A necropsy was performed, and the findings revealed right lobar pneumonia with a necrotizing hemorrhage of the entire right lung and one-half of the left lung. A culture specimen from tracheal aspirates grew methicillin-susceptible S. aureus.

Identification of S. aureus was based on colony morphology, coagulation of citrated rabbit plasma (bioMérieux), and production of clumping factor (determined with the Staphyslide test; bioMérieux). The methicillin resistance was determined by the Kirby-Bauer disk-diffusion method, with the use of a 5-µg oxacillin disk, in accordance with the NCCLS recommendations [2], after 24–48 h of incubation at 35°C. The S. aureus isolate was only resistant to penicillin and amoxicillin and was susceptible to methicillin, aminosides, macrolides, quinolones, and cotrimoxazole.

On day 5, the physician who had performed intubation presented with numerous furuncles of the fingers and face. Samples were obtained from the skin lesions. At the same time, nasal samples were obtained from the 15 health care workers who had participated in the resuscitation. S. aureus strains susceptible to methicillin were isolated from samples from the physician and from 5 other health care workers. The isolate from the infant (S1, isolated from a tracheal sample) and 7 isolates from the 6 health care workers (S2, isolated from skin lesions of 1 physician; S4 and S5, from nasal and anal samples from another physician; and S3, S6, S7, and S8, from nasal samples from 4 nurses) were genotyped and analyzed for the presence of the PVL gene.

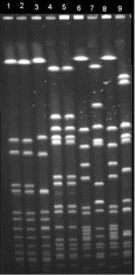

PFGE, used for genotyping, was performed on DNA fragments obtained by digestion with the restriction enzyme SmaI by use of a CHEF-MAPPER apparatus. The PFGE banding patterns were compared visually. Strains were considered genetically distinguishable if their restriction patterns differed by ⩾3 bands [3]. The isolates from the infant (S1) and from 1 physician (S2) were genetically related and were unrelated to the other isolates (S3–S8) and the control strain (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PFGE fluorogram of 9 strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Isolates are from a tracheal sample from the infant (lane 1), a skin lesion from 1 physician (lane 2), a nasal sample from 1 nurse (lane 3), nasal and anal samples from another physician (lanes 4 and 5), and nasal samples from 3 other nurses (lanes 6–8). Lane 9, an unrelated S. aureus isolate.

The presence of the PVL gene was determined by use of a PCR method described elsewhere [4]. As expected, a fragment of 433 bp was obtained from the S. aureus isolates from the infant (S1) and the physician (S2) but not from the isolates from the other health care workers.

Discussion. This report describes the transmission of a PVL-producing S. aureus strain from a patient to a health care worker during resuscitation. Previous studies have reported transmission of different pathogens during mouth-to-mouth resuscitation: Salmonella [5], Herpes simplex [6], Helicobacter pylori [7], and more recently, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [8]. In the present case, it is likely that transmission was related to the events leading up to intubation, and contact, droplet, or airborne transmission might have occurred. The transmission might have been promoted by the particular pathogenicity of PVL-producing strain. The transmission of the S. aureus strain to the physician was revealed by furunculosis. As previously reported, most cases of furunculosis (93%) are due to PVL-producing S. aureus [1]. Unfortunately, no nasal sample was obtained from this physician. This study highlights the necessity for health care workers to protect themselves against transmission of pathogens from patient to care giver, even in situations where benign infection is suspected.

Acknowledgments

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P, et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet. 2002;359:753–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07877-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCCLS . Method for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 5th ed. Wayne, PA: NCCLS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1128–32. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad F, Senadhira DC, Charters J, Acquilla S. Transmission of Salmonella via mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Lancet. 1990;335:787–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90898-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendricks AA, Shapiro EP. Primary Herpes simplex infection following mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. JAMA. 1980;243:257–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figura N. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and Helicobacter pylori infection. Lancet. 1996;347:1342. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90996-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christian MD, Loufty M, McDonald C, et al. Possible SARS coronavirus transmission during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:287–93. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]