SIR—We read with interest the report by Yap et al. [1] regarding the increased rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolation in the intensive care unit (ICU) during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong. The SARS outbreak in Singapore, which lasted from 4 March 2003 to 11 May 2003, also led to the adoption of heightened infection-control measures, including mandatory universal use of personal protective equipment (PPE) consisting of disposable long-sleeved gowns, gloves, goggles, and N95 masks by health care workers for all patient contacts. Compulsory training on the proper donning and discarding of PPE was instituted, and compliance with hand washing was reinforced. Observers were employed to ensure that these measures were followed by the ward staff. In addition, all patients with undifferentiated fever were nursed in single isolation rooms until the cause of their fever was ascertained. Whereas the data reported by Yap et al. [1] was confined to the ICU, we studied the effect of these measures on hospital-wide nosocomial MRSA infection and bacteremia rates in the National University Hospital, a 1000-bed teaching facility in Singapore.

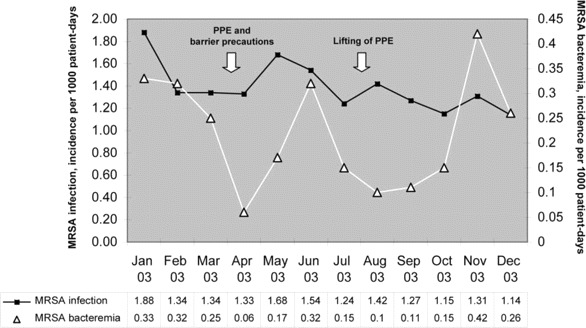

MRSA bacteremia and infection rates were determined by surveillance of nonduplicative isolates identified in the microbiology laboratory from January 2003 through December 2003 (figure 1). Hand washing compliance was determined by trained observers in 2 surveys involving a total of 1004 subjects; the first survey, involving 829 subjects, was done in February 2003 (before the SARS outbreak), and the second survey, involving 175 subjects, was done in June 2003 (after the SARS outbreak). The overall rate of compliance with hand washing increased from 33.4% in February 2003 to 87.4% in June 2003 (P = .01). However, we too were unable to detect a corresponding decrease in MRSA infection rates (figure 1). Paradoxically, increases in the rates of MRSA infection and possibly MRSA bacteremia were observed, despite the use of intense infection-control measures during the epidemic period.

Figure 1.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia and infection rates, 2003. PPE, personal protective equipment.

Like the findings reported by Yap et al. [1], our findings seem to suggest that the universal use of gloves and gowns did not produce the expected decrease in the rate of nosocomial cross-infection [2, 3]. Although protective to health care workers, inanimate objects (such as gloves and gowns) have been implicated as reservoirs of MRSA [4, 5]. In addition, although we were able to document a marked improvement in hand hygiene compliance, we were unable to show expected reductions in the rate of nosocomial infection [6, 7]. We suspect that despite—or perhaps because of—the increased emphasis on hand hygiene, compliance with glove change between patient contacts was reduced, and this may have led to increased transmission of multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogens on the gloved hands of health care workers [5]. Another possible explanation for the paradoxical increase in MRSA rates during the SARS outbreak could be the shunting of limited infection-control resources to SARS case surveillance and epidemiology and away from mainstream infection-control activities, thus compromising the effectiveness of baseline control measures against nosocomial infections.

As our data reinforce, during periods of intense alert for novel emerging pathogens, such as SARS coronavirus and avian influenza virus, it is imperative that “conventional” practices of infection control not be overlooked, because they remain essential for the control of infection with endemic nosocomial pathogens in our midst.

Acknowledgments

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Yap FHY, Gomersall CD, Fung KSC, et al. Increase in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition rate and change in pattern associated with an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:511–6. doi: 10.1086/422641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce JM, Havill NL, Kohan C, et al. Do infection control measures work for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:395–401. doi: 10.1086/502412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman DA. The role of barrier precautions in infection control. J Hosp Infect. 1991;18(Suppl A):515–23. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(91)90065-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horikawa K, Murakami K, Kawano F. Isolation and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from the nares of nurses and their gowns. Microbiol Res. 2001;155:345–9. doi: 10.1016/S0944-5013(01)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyce JM, Potter-Bynoe G, Chenevert C, et al. Environmental contamination due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: possible infection control implications. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:622–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittet D, Mourouga P, Perneger TV. Compliance with handwashing in a teaching hospital. Infection Control Programme. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:126–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-2-199901190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbarth S, et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Infection Control Programme. Lancet. 2000;356:1307–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]