Abstract

Background. A new human-pathogenic parvovirus, human bocavirus (HBoV), has recently been discovered and associated with respiratory disease in small children. However, many patients have presented with low viral DNA loads, suggesting HBoV persistence and rendering polymerase chain reaction-based diagnosis problematic. Moreover, nothing is known of HBoV immunity. We examined HBoV-specific systemic B cell responses and assessed their diagnostic use in young children with respiratory disease.

Patients and methods. Paired serum samples from 117 children with acute wheezing, previously studied for 16 respiratory viruses, were tested by immunoblot assays using 2 recombinant HBoV capsid antigens: the unique part of virus protein 1 and virus protein 2.

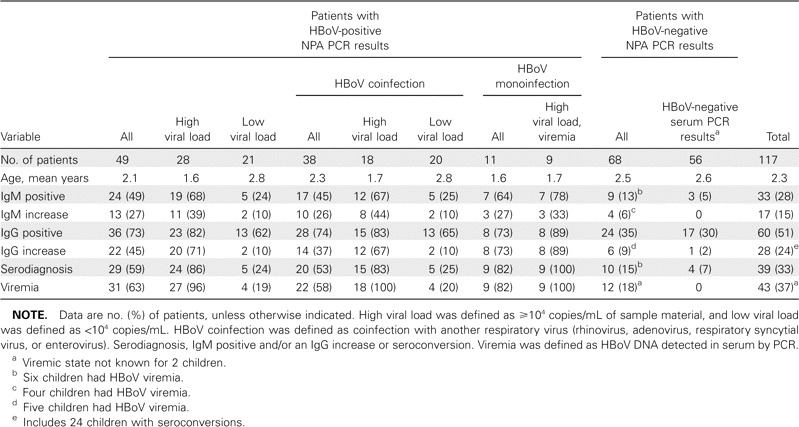

Results. Virus protein 2 was superior to the unique part of virus protein 1 with respect to immunoreactivity. According to the virus protein 2 assay, 24 (49%) of 49 children who were positive for HBoV according to polymerase chain reaction had immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies, 36 (73%) had IgG antibodies, and 29 (59%) exhibited IgM antibodies and/or an increase in IgG antibody level. Of 22 patients with an increase in antibody levels, 20 (91%) had a high load of HBoV DNA in the nasopharynx, supporting the hypothesis that a high HBoV DNA load indicates acute primary infection, whereas a low load seems to be of less clinical significance. In a subgroup of patients who were previously determined to have acute HBoV infection (defined as a high virus load in the nasopharynx, viremia, and absence of other viral infections), 9 (100%) of 9 patients had serological evidence of primary infection. In the control group of 68 children with wheezing who had polymerase chain reaction results negative for HBoV in the nasopharynx, 9 (13%) had IgM antibodies, including 5 who displayed an increase in IgG antibody levels and were viremic. No cross-reactivity with human parvovirus B19 was detected.

Conclusions. Respiratory infections due to HBoV are systemic, elicit B cell immune responses, and can be diagnosed serologically. Serological diagnoses correlate with high virus loads in the nasopharynx and with viremia. Serological testing is an accurate tool for disclosing the association of HBoV infection with disease.

Viral infections of the lower airways are a major cause of morbidity and even mortality in infants and small children. The classical perpetrators are rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus, but interesting newcomers, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, human metapneumovirus, and, more recently, human bocavirus (HBoV), also cause severe disease. HBoV was discovered in 2005 from pooled nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) by a procedure named molecular virus screening, including random PCR, large-scale sequencing, and bioinformatics [1]. Subsequent sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the HBoV genomic DNA showed that the virus is taxonomically closest to the newly established genus Bocavirus of the Parvoviridae family. It is the second human-pathogenic parvovirus known. The first, parvovirus B19, causes rash, arthropaties, anemias, and fetal death. Other human parvoviruses include the adeno-associated viruses and the newly found parvovirus 4, which have unknown clinical impact [2, 3]. The closest relatives of HBoV are the bocaviruses bovine parvovirus and canine minute virus, which infect cows and dogs, respectively [1]. The animal bocavirus infections are mostly subclinical. However, diseases associated with canine minute virus or bovine parvovirus include reproductive failure, enteritis, and neonatal respiratory disease [4– 8].

Since its discovery, HBoV has been shown worldwide to be one of the most common viruses in respiratory secretions, with DNA prevalences of 1%– 19%, depending greatly on the study design, including laboratory technology, patient age, and symptoms. HBoV is typically found in children ⩽ 3 years of age who are hospitalized for lower respiratory tract disease [9– 16], whereas healthy children and adults have generally had PCR results that are negative for HBoV [12, 17– 21]. Thus, growing evidence exists for HBoV being a human-pathogenic virus causing acute lower respiratory diseases in infants and young children. However, a large number of patients have presented with low viral loads [17, 22– 24], suggesting HBoV persistence and making PCR-based diagnosis problematic. Nevertheless, all studies performed with this virus so far have been based on PCR detection, and little is known of HBoV-specific B cell immunity [25]. The aim of our study was to find out whether symptomatic HBoV infections in pediatric patients elicit systemic antibody responses and whether these responses can be used for diagnosis of HBoV infections in children with respiratory disease.

Patients, Materials, and Methods

Patients and sample collection. Children aged 3 months to 15 years who were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics of Turku University Hospital (Turku, Finland) from 1 September 2000 through 31 May 2002 for acute expiratory wheezing have been observed and described elsewhere [17, 26]. At admission to the hospital, NPAs for viral diagnosis were obtained by a standard procedure [26]. Blood samples were collected at hospital admission and 2– 3 weeks after hospital discharge, and the paired serum samples were stored at − 20° C. Of the 259 children who were included in the previous virus etiology study, comprising PCR studies of NPAs for 16 viruses (adenovirus; HBoV; coronaviruses 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1; enteroviruses; rhinoviruses; influenza A and B viruses; human metapneumovirus; parainfluenza virus 1– 4; and respiratory syncytial virus), 49 (19%) of 259 were shown to be HBoV positive by PCR [17]. Paired serum samples from these 49 HBoV-positive children (mean age, 2.1 years; range, 5 months to 11 years) were available for the present study. Paired serum samples from 68 randomly selected wheezing children (mean age, 2.5 years; range, 5 months to 12 years) who had NPAs with HBoV-negative PCR results in the same study were included as control subjects. The duration of symptoms (e.g., cough) prior to hospital admission was a mean of 4.8 days (range, 0– 28 days) and the hospitalization time was a mean of 28.6 h (range, 0– 138 h), based on data available for 112 children. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Turku University Hospital (Turku, Finland) and Helsinki University Hospital (Helsinki, Finland).

Recombinant antigen production. The full-length virus protein 2 (VP2) and the unique region of virus protein 1 (VP1u) HBoV capsid genes (corresponding to nucleotides 3443– 5071 and 3056– 3442, respectively) were amplified by high-fidelity PCR from a plasmid containing a near full-length HBoV clone (GenBank accession no. DQ000496). The primers included recognition sites for the restriction enzymes (table 1). The amplicons were cloned into the His6/T7-fusion expression vector pET23b (Novagen) using standard cloning practices and transformed into the Escherichia coli expression host BL21(DE3) pLysS (Invitrogen). For protein production, the E. coli strains harboring VP1u and VP2 were kept shaking at 37° C in 0.5 l Luria broth or Terrific broth medium, respectively, containing 50 µ g/mL of ampicillin and 34 µ g/mL of chloramphenicol. When the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5, they were induced for 3 h with 0.4 mM isopropyl β -D-thiogalactoside. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (10 min at 10,000 g at room temperature), resuspended in 25 mL of PBS, and lysed by sonication on ice. The His6/T7-tagged proteins were purified under denaturing conditions by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer' s instructions.

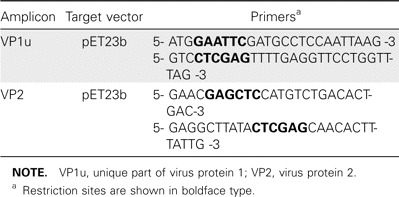

Table 1.

Primer sequences used to amplify the capsid genes for cloning.

Serological testing. For the immunoblot assays, purified protein samples were separated by PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Protran BA 85; Whatman, Schleicher & Schuell), which were blocked for 30 min with blocking buffer (5% dry milk and 0.2% Triton-X-100 in PBS) at room temperature and then treated with the human serum samples in blocking buffer (IgG, dilution 1:50; IgM, dilution 1:30) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antihuman IgG or IgM, diluted in blocking buffer (1:500), was added, and peroxidase activity was demonstrated by 3,3' -diaminobenzidine and H2O2. After each step, the sheet was washed 3 times for 10 min each with PBS containing 0.05% Tween. Stained bands were visualized and regarded as negative or positive (equivocal results were considered to be negative). The scoring was done before knowledge of the results of PCR for HBoV.

All serum samples were also tested for parvovirus B19 IgM and IgG antibodies with commercial (IgG and IgM; Biotrin) and in-house (epitope type-specific IgG and β -VP1) EIAs [27– 30].

Quantitative PCR. Most of the paired serum samples from children with NPAs positive for HBoV by PCR had been studied earlier by a quantitative PCR targeting the NP1 gene [17]. All of the remaining serum samples (except for samples from 2 children, which were unavailable) underwent HBoV DNA amplification. DNA was purified from 50 µ L of serum with the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen) and eluted in 50 µ L, of which 5 µ L was used in a total reaction volume of 25 µ L. The TaqMan universal PCR master mix (PE Applied Biosystems) was used, and the PCR was performed according to Allander et al. [17], except that the thermal cycler was Mx3005P QPCR System (Stratagene), and the settings were 95° C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95° C for 15 s and 60° C for 1 min. A positive quantifiable result was obtained with as few as 10 copies/µ L of the HBoV ST2-containing plasmid [1]. To avoid contamination, the samples and the PCR mixtures were prepared under laminar flow hoods in separate rooms. Water was used as a negative control.

Results

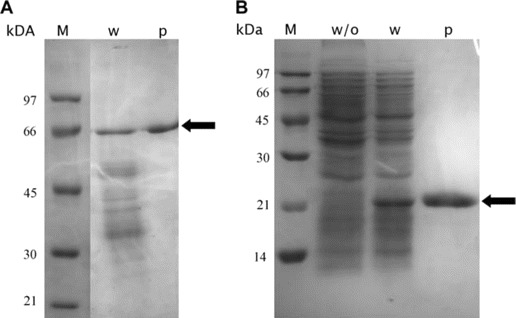

Expression of HBoV proteins. The VP1u and VP2 proteins were expressed in bacteria, and the expression was analyzed by SDS PAGE (figure 1). The his6/T7-tagged VP1u and VP2 showed the apparent molecular weights of ∼ 20 kDa and 65 kDa, respectively. The protein yield was good in both cases, with a 500-mL culture sample resulting in ∼ 8 mg of affinity purified recombinant protein.

Figure 1.

Coomassie blue-stained SDS PAGE showing the prokaryotically expressed virus protein 2 (VP2) (A) and the unique part of virus protein 1 (VP1u) (B). Arrows indicate VP1u and VP2. M, molecular weight standard; p, affinity purified protein; w, lysate with expressed VP gene; w/o, lysate without virus protein gene.

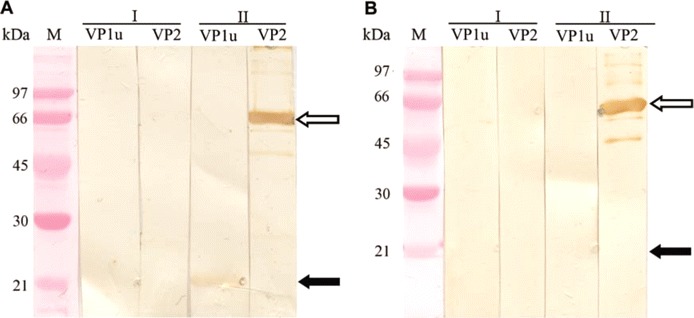

HBoV immunoblot. The paired serum samples of the 117 wheezing children were applied onto immunoblot membranes harboring as antigens the 2 recombinant HBoV capsid proteins, VP1u and VP2, for the detection of human bocavirus-specific IgG and IgM antibodies (representative results are shown in figure 2). In all, 60 (51%) of 117 children had IgG antibodies and 33 (28%) of 117 had IgM antibodies for the major capsid protein VP2 (table 2). The VP2 immunoblot results were compared with the previous results of PCR of NPAs [17], as shown in table 2. Among the 49 children with HBoV-positive results of PCR of NPAs, 29 (59%) of 49 had diagnostic antibody results (24 [49%] of 49 had HBoV-specific IgM antibodies, and 22 [45%] of 49 had a detectable increase in IgG antibodies). Of the 22 children with increases in IgG, 19 actually experienced seroconversion, and 17 (77%) also exhibited IgM antibodies. All but 1 of the serodiagnoses (97%) occurred in children aged ⩽ 3 years.

Figure 2.

Representative results of human bocavirus (HBoV) IgG (A) and IgM (B) immunoblotting, using virus protein 1 (VP1u) or virus protein 2 (VP2) antigen-harboring membranes, as indicated. Membrane strips were treated with the first (I) and second (II) samples of serum pairs and show IgG conversions for both VP1u and VP2 (A) and the appearance of IgM for VP2 (B). Black and white arrows indicate the positions of the VP1u and VP2 antigens, respectively. M, molecular weight.

Table 2.

Human bocavirus (HBoV) virus protein 2 (VP2) immunoblot results for 117 wheezing children, compared with nasopharyngeal aspirate (NPA) [17] and serum PCR results for HBoV.

Allander et al. [17] suggested that a high HBoV DNA load in NPAs (⩾ 104 copies/mL) indicated a primary symptomatic infection, whereas a lower viral load likely reflected virus persistence. The group with HBoV-positive PCR results was, therefore, subdivided according to the DNA load in the NPAs; 24 (86%) of 28 of the group with high viral loads exhibited a diagnostic antibody result, compared with 5 (24%) of 21 patients in the low viral load group (table 2). Of the 22 patients with IgG antibody increases or seroconversions, 20 (91%) were in the high viral load group. Furthermore, in the group of children with HBoV as the sole PCR finding (HBoV monoinfection in table 2), 9 (82%) of 11 had diagnostic results; 7 (64%) of 11 had IgM antibodies, and 8 (73%) of 11 had an increase in IgG antibody level (7 of whom experienced seroconversion). (Of the 12 patients initially regarded as having HBoV monoinfection [17], 1 was later found to harbor a nontypable picornavirus.) Of note, of the 9 viremic children with a high load of DNA in their NPAs and with HBoV as the only PCR finding, 100% had an HBoV serodiagnosis. Among the children who had PCR results positive for HBoV and were coinfected with another respiratory virus, 20 (53%) of 38 had an HBoV serodiagnosis (table 2). Of the 49 children with PCR-positive NPAs, 31 (63%) had serum samples with positive PCR results (table 2), with DNA levels ranging from 1× 102 to 1× 105 copies/mL [17].

In the control group of 68 children with HBoV-negative NPAs according to PCR, 10 (15%) of 68 had a diagnostic result; 9 (13%) of 68 had IgM antibodies, and 6 (9%) of 68 had an increase in IgG antibody level (5 of whom experienced seroconversion) (table 2). Of note, of these 6 control patients with IgG increases, 5 had serum samples with PCR results that were positive for HBoV (i.e., these particular control patients indeed had an ongoing HBoV infection, even though they had NPAs that were reproducibly PCR negative). In all, 12 (18%) of the 68 children with PCR-negative NPAs were viremic, with viral loads up to 106 copies/mL (table 2).

The total prevalence of HBoV VP2 IgG was 35% (or 29% if only the first serum samples are included) in the group of wheezing children with HBoV-negative NPAs according to PCR (mean age, 2.5 years; range, 5 months to 12 years). The seroprevalences among the different age groups were as follows: < 6 months of age, 0% (n=3); 6– 12 months of age, 17% (n=12); 1– 2 years of age, 52% (n=21); 2– 3 years of age, 43% (n=14); 3– 5 years of age, 27% (n=11); and >5 years of age, 29% (n=7).

According to the VP1u antibody assay, only 8 (7%) of 117 children had IgG, 2 (2%) of 117 had IgM, and 3 (3%) of 117 had an increase in IgG (1 of whom is described in figure 2A). The 5 VP1u serodiagnoses did not correlate with the NPA PCR results, but all of the serodiagnoses occurred in children with viremia and a VP2 diagnostic result (data not shown). Seven of the 8 VP1u IgG– positive children had IgG antibodies to the VP2 antigen.

B19 serological testing. All serum samples were studied for parvovirus B19-VP1u and -VP2 IgM and IgG antibodies. No diagnostic B19 findings (positive IgM or low epitope-type specificity index [28, 29]) were seen among the children with HBoV serodiagnoses. In our entire clinical material, a single B19 diagnosis was encountered, in a 6-year-old HBoV-seronegative child in the control group. Altogether, of the 20 (17%) of 117 children with B19 IgG antibodies, 6 had HBoV IgG antibodies, and of the 60 children with HBoV IgG antibodies, only 6 (10%) had B19 IgG antibodies, compared with 14 (25%) of the 57 HBoV IgG– negative children (data not shown).

Discussion

We have successfully expressed and purified the HBoV major capsid protein VP2 in full length, and the unique part of the minor capsid protein VP1, which together span the entire putative capsid-protein coding region. The proteins were used for the detection of human bocavirus-specific IgG and IgM antibodies in paired serum samples from children with acute wheezing. Among 117 wheezing children, 2 major groups with similar age distributions were compared; 49 children who harbored bocavirus DNA in the nasopharynx and 68 who did not [17]. The group of children with HBoV-positive PCR results was further subdivided according to the amount of HBoV DNA detected and also according to whether HBoV was the sole finding, as outlined in table 2.

The antibody results showed that the VP2 antigen is superior in immunoreactivity to VP1u. This was surprising in comparison with the other human-pathogenic parvovirus, B19, in which the VP1u is very immunoreactive [30] and contains many neutralizing epitopes [31– 35]. Indeed, both VP2 and the VP1u region have been successfully used in the diagnosis of B19 infections [30, 36– 38]. One possible reason for the dissimilarity between the 2 viruses might be a difference in the location of VP1u within the capsid [34, 39, 40], which could affect its accessibility to host immunity. With the HBoV VP1u immunoblot assay, the overall seroprevalence rate was as low as 7%, with no correlation with HBoV-positive NPAs by PCR. However, the VP1u assay seemed to be specific; all 5 diagnoses were confirmed by the VP2 assay and by PCR of serum samples.

By contrast, with the VP2 assay, >70% of the children with HBoV-positive NPAs by PCR were seropositive, and more than one-half of them exhibited markers (IgM antibodies or increasing IgG antibody level) of acute viral infection. Most of these serodiagnoses (24 of 29) occurred in children with a high virus load. Furthermore, among our group of 117 wheezing children, 9 fulfilled all 3 nonserological criteria for acute HBoV infection, including viremia, high viral load in NPAs, and lack of other viruses. Of the patients in this subgroup, 100% showed serological evidence of acute infection.

In the control group with NPAs that were HBoV-negative by PCR, only 6 children (9%) showed a diagnostic IgG increase. Of note, 5 of these were found to have HBoV-positive serum samples by PCR, indicating an ongoing systemic HBoV infection. In total, 12 (18%) of the wheezing children with HBoV-negative NPAs by PCR were viremic, further emphasizing the need for other diagnostic tools. Even if technical problems in PCR and clinical sampling (or its timing) cannot be ruled out as possible explanations for the PCR negativity of these serodiagnostic and viremic cases, an interesting alternative explanation could be a systemic HBoV infection without virus shedding in the respiratory tract. Indeed, the high prevalence of NPAs with HBoV-positive PCR results [17] and the high number of seroconversions in the group with high viral loads suggest that our sampling and its timing, in general, were appropriate.

On the other hand, there were 20 patients who had NPAs with HBoV-positive PCR results, almost all of whom had low virus loads, without a serodiagnosis. Of these 20 children, 17 were also nonviremic. This could have several explanations (e.g., a superficial infection without systemic immunization or persistence of viral DNA in the nasopharynx following an earlier infection). HBoV in this age group is common [9, 10, 14– 16, 24] and could be widely circulating among children in day care or within families, thereby easily contaminating airways.

In line with the high frequency of PCR results positive for HBoV is the high prevalence of coinfections with other respiratory viruses [9– 12, 14, 17, 18]. Indeed, among the wheezing children in our study, not only most of the patients with HBoV monoinfection, but also one-half of those who were coinfected with other viruses, exhibited a serodiagnosis of HBoV infection, indicating that HBoV also occurs systemically in individuals with coinfection and should be considered in the diagnosis of respiratory disease.

The prevalence of HBoV IgG in the group of wheezing children who had NPAs with PCR results negative for HBoV (mean age, 2.5 years; range, 5 months to 12 years), based on our VP2 assay, was 35%. However, this cannot be regarded as a general HBoV seroprevalence in this age group because of the fact that all of our children had been enrolled on the basis of their respiratory symptoms. According to PCR, acute HBoV infection has been shown to be most prevalent in children aged 6 months to 3 years [9– 16]. It is possible that children ⩽ 6 months of age are protected by maternal antibodies. In our study, however, only 5 children were as young as 5– 6 months of age (2 in the coinfection group and 3 in the control group), and none were HBoV seropositive. The seroprevalence seemed to increase with age, reaching a maximum of 52% among children 1– 2 years of age and then decreasing to 27% among children 3– 5 years of age. This decrease suggests that the denatured antigen, which is inherent to the immunoblot method, might not be recognized by the past immunity antibodies of the older children. Such a time-related conformational dependence is characteristic for the B cell immunity of the B19 virus [27– 29, 41, 42]. This phenomenon, in addition to the superficial mucosal infection, could also explain why not all patients with low viral loads were IgG positive, in line with the hypothesis of virus persistence long after infection.

Some evidence of serological cross-recognition between human and bovine parvoviruses and, more specifically, between B19 and the bocavirus bovine parvovirus has been observed [8, 43], even though the latter 2 viruses are phylogenetically distant and their capsid protein sequence similarity is low [44]. To ensure that antibodies to B19 would not cross-react with HBoV (and, thus, interfere with our results), all children were examined for B19 B cell immunity. However, there were more B19 IgG– positive children among the HBoV IgG– negative group than among the HBoV IgG– positive group. Furthermore, no children were found to be positive for both B19 and HBoV IgM. Therefore, among our patients, B19 antibodies did not interfere with the HBoV antibody results.

Allander et al. [17] found HBoV DNA in the NPAs of 49 (19%) of 259 wheezing children, 28 (11%) of whom had high HBoV DNA loads, and 12 (5%) of whom were infected with HBoV only. Infections associated with low virus loads were, however, prevalent and were suggested to reflect virus persistence. High viral load and viremia were noted mainly in the absence of other respiratory viruses, suggesting a causative role for HBoV in acute wheezing. In the present study, serodiagnostic findings strongly support this causality. A low viral load in the nasopharynx thus seems to be of little clinical significance. Even though the VP2 immunoblot assay used here is not intended to be the final diagnostic tool, our findings clearly show the diagnostic value of serological testing in acute HBoV infection. The diagnostic criteria for a bocavirus infection are currently unsettled. Using only HBoV-positive PCR results in NPAs as the criterion, some cases of acute HBoV infection (evidenced by viremia and/or serodiagnostic findings) would be missed. Furthermore, a number of false diagnoses would be obtained, perhaps as the result of persisting HBoV DNA or mucosal contamination. Serological testing, coupled with quantitative PCR, should be included in diagnostics, as shown here, to strengthen the causal association between HBoV and respiratory disease. With this combination of diagnostic tools, it is now possible to also evaluate other clinical manifestations possibly caused by HBoV, such as pediatric gastroenteritis [45]. Whether, and in which context and to what extent, this virus affects immunocompromised individuals, pregnant women, and elderly individuals is currently unknown. Additional knowledge of the neutralizing capacity and the longevity of HBoV immunity is also required.

It is here shown, to our knowledge for the first time, that respiratory infections due to HBoV elicit a systemic B cell response, comprising both IgM and IgG. We also show that the main target for this response is the major capsid protein VP2, whereas the unique region of the minor protein, VP1u, is less immunoreactive. By measurement of HBoV-specific antibodies, it is possible to identify acute HBoV infections in small children hospitalized for severe respiratory disease. For maximum diagnostic power, both quantitative PCR and serological testing should be performed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaisa Kemppainen and Kaisu Kaistinen for technical help.

Financial support. Helsinki University Central Hospital Research & Education and Research & Development funds, the Sigrid Jusé lius Foundation, and the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (to K.K., L.H., K.H., and M.S.V.); the Torsten and Ragnar Sö derberg Foundation (to T.A.); and the Academy of Finland (to O.R., T.J., and P.L.; project code 1122539 for K.K., L.H., K.H., and M.S.V.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:12801–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones MS, Kapoor A, Lukashov VV, Simmonds P, Hecht F, Delwart E. New DNA viruses identified in patients with acute viral infection syndrome. J Virol. 2005;79:8230–6. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8230-8236.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning A, Willey SJ, Bell JE, Simmonds P. Comparison of tissue distribution, persistence, and molecular epidemiology of parvovirus B19 and novel human parvoviruses PARV4 and human bocavirus. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1345–52. doi: 10.1086/513280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes MA, Wright RE, Bodine AB, Alberty CF. Frequency of bluetongue and bovine parvovirus infection in cattle in South Carolina dairy herds. Am J Vet Res. 1982;43:1078–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison LR, Styer EL, Pursell AR, Carmichael LE, Nietfeld JC. Fatal disease in nursing puppies associated with minute virus of canines. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:19–22. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mochizuki M, Hashimoto M, Hajima T, et al. Virologic and serologic identification of minute virus of canines (canine parvovirus type 1) from dogs in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3993–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.3993-3998.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrish CR. Minute virus of canines (canine minute virus): the virus and its disease. In: Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. London: Hodder Arnold Publishers; 2006. pp. 473–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Via LE, Mainguy C, Naides S, Lederman M. Bovine parvovirus. In: Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. London: Hodder Arnold Publishers; 2006. pp. 479–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arden KE, McErlean P, Nissen MD, Sloots TP, Mackay IM. Frequent detection of human rhinoviruses, paramyxoviruses, coronaviruses, and bocavirus during acute respiratory tract infections. J Med Virol. 2006;78:1232–40. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold JC, Singh KK, Spector SA, Sawyer MH. Human bocavirus: prevalence and clinical spectrum at a children' s hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:283–8. doi: 10.1086/505399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma X, Endo R, Ishiguro N, et al. Detection of human bocavirus in Japanese children with lower respiratory tract infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1132–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1132-1134.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manning A, Russell V, Eastick K, et al. Epidemiological profile and clinical associations of human bocavirus and other human parvoviruses. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1283–90. doi: 10.1086/508219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qu XW, Duan ZJ, Qi ZY, et al. Human bocavirus infection, People' s Republic of China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:165–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloots TP, McErlean P, Speicher DJ, Arden KE, Nissen MD, Mackay IM. Evidence of human coronavirus HKU1 and human bocavirus in Australian children. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smuts H, Hardie D. Human bocavirus in hospitalized children, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1457–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1209.051616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weissbrich B, Neske F, Schubert J, et al. Frequent detection of bocavirus DNA in German children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allander T, Jartti T, Gupta S, et al. Human bocavirus and acute wheezing in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:904–10. doi: 10.1086/512196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fry AM, Lu X, Chittaganpitch M, et al. Human bocavirus: a novel parvovirus epidemiologically associated with pneumonia requiring hospitalization in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1038–45. doi: 10.1086/512163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesebir D, Vazquez M, Weibel C, et al. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1276–82. doi: 10.1086/508213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maggi F, Andreoli E, Pifferi M, Meschi S, Rocchi J, Bendinelli M. Human bocavirus in Italian patients with respiratory diseases. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:321–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon A, Groneck P, Kupfer B, et al. Detection of bocavirus DNA in nasopharyngeal aspirates of a child with bronchiolitis. J Infect. 2007;54:e125–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foulongne V, Rodiere M, Segondy M. Human bocavirus in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:862–3. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin F, Zeng A, Yang N, et al. Quantification of human bocavirus in lower respiratory tract infections in China. Infect Agent Cancer. 2007;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu X, Chittaganpitch M, Olsen SJ, et al. Real-time PCR assays for detection of bocavirus in human specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3231–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00889-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Endo R, Ishiguro N, Kikuta H. Seroepidemiology of human bocavirus in Hokkaido prefecture, Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3218–23. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02140-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jartti T, Lehtinen P, Vuorinen T, et al. Respiratory picornaviruses and respiratory syncytial virus as causative agents of acute expiratory wheezing in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1095–101. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.030629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enders M, Schalasta G, Baisch C, et al. Human parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy: value of modern molecular and serological diagnostics. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:400–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaikkonen L, Lankinen H, Harjunpä ä I, et al. Acute-phase-specific heptapeptide epitope for diagnosis of parvovirus B19 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3952–6. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3952-3956.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sö derlund M, Brown CS, Spaan WJM, Hedman L, Hedman K. Epitope type-specific IgG responses to capsid proteins VP1 and VP2 of human parvovirus B19. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1431–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sö derlund M, Brown KE, Meurman O, Hedman K. Prokaryotic expression of a VP1 polypeptide antigen for diagnosis by a human parvovirus B19 antibody enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:305–11. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.305-311.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson S, Momoeda M, Kawase M, Kajigaya S, Young NS. Peptides derived from the unique region of B19 parvovirus minor capsid protein elicit neutralizing antibodies in rabbits. Virology. 1995;206:626–32. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bansal GP, Hatfield JA, Dunn FE, et al. Candidate recombinant vaccine for human B19 parvovirus. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1034–44. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajigaya S, Fujii H, Field A, et al. Self-assembled B19 parvovirus capsids, produced in a baculovirus system, are antigenically and immunogenically similar to native virions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4646–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenfeld SJ, Yoshimoto K, Kajigaya S, et al. Unique region of the minor capsid protein of human parvovirus B19 is exposed on the virion surface. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:2023–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI115812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saikawa T, Anderson SM, Momoeda M, Kajigaya S, Young NS. Neutralizing linear epitopes of B19 parvovirus cluster in the VP1 unique and VP1-VP2 junction regions. J Virol. 1993;67:3004–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3004-3009.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown CS, Salimans MMM, Noteborn MHM, Weiland HT. Antigenic parvovirus B19 coat proteins VP1 and VP2 produced in large quantities in a baculovirus expression system. Virus Res. 1990;15:197–212. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(90)90028-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rayment FB, Crosdale E, Morris DJ, Pattison JR, Talbot P, Clare JJ. The production of human parvovirus capsid proteins in Escherichia coli and their potential as diagnostic antigens. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2665–72. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-11-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sö derlund M, Brown CS, Cohen BJ, Hedman K. Accurate serodiagnosis of B19 parvovirus infections by measurement of IgG avidity. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:710–3. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawase M, Momoeda M, Young NS, Kajigaya S. Most of the VP1 unique region of B19 parvovirus is on the capsid surface. Virology. 1995;211:359–66. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ros C, Gerber M, Kempf C. Conformational changes in the VP1-unique region of native human parvovirus B19 lead to exposure of internal sequences that play a role in virus neutralization and infectivity. J Virol. 2006;80:12017–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01435-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corcoran A, Mahon BP, Doyle S. B cell memory is directed toward conformational epitopes of parvovirus B19 capsid proteins and the unique region of VP1. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1873–80. doi: 10.1086/382963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manaresi E, Zuffi E, Gallinella G, Gentilomi G, Zerbini M, Musiani M. Differential IgM response to conformational and linear epitopes of parvovirus B19 VP1 and VP2 structural proteins. J Med Virol. 2001;64:67–73. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mengeling WL, Paul PS. Antibodies for autonomous parvoviruses of lower animals detected in human serum. Arch Virol. 1986;88:127–33. doi: 10.1007/BF01310897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapman MS, Rossmann MG. Structure, sequence, and function correlations among parvoviruses. Virology. 1993;194:491–508. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vicente D, Cilla G, Montes M, Pé rez-Yarza EG, Pé rez-Trallero E. Human bocavirus, a respiratory and enteric virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:636–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]